Key Points

Hydroxyurea activates nuclear factor–κB to transcriptionally upregulate SAR1.

SAR1, in turn, activates γ-globin expression through the Giα/JNK/Jun pathway.

Abstract

Hydroxyurea (HU) is effectively used in the management of β-hemoglobinopathies by augmenting the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying HU-mediated HbF regulation remain unclear. We previously reported that overexpression of the HU-induced SAR1 gene closely mimics the known effects of HU on K562 and CD34+ cells, including γ-globin induction and cell-cycle regulation. Here, we show that HU stimulated nuclear factor-κB interaction with its cognate-binding site on the SAR1 promoter to regulate transcriptional expression of SAR1 in K562 and CD34+ cells. Silencing SAR1 expression not only significantly lowered both basal and HU-elicited HbF production in K562 and CD34+ cells, but also significantly reduced HU-mediated S-phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in K562 cells. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/Jun phosphorylation and silencing of Giα expression in SAR1-transfected K562 and CD34+ cells reduced both γ-globin expression and HbF level, indicating that activation of Giα/JNK/Jun proteins is required for SAR1-mediated HbF induction. Furthermore, reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation assays revealed an association between forcibly expressed SAR1 and Giα2 or Giα3 proteins in both K562 and nonerythroid cells. These results indicate that HU induces SAR1, which in turn activates γ-globin expression, predominantly through the Giα/JNK/Jun pathway. Our findings identify SAR1 as an alternative therapeutic target for β-globin disorders.

Introduction

β-hemoglobinopathies are inherited disorders caused by mutations/deletions in the β-globin chain that lead to structurally defective β-globin chains or reduced (or absent) β-globin chain production.1,2 These diseases affect multiple organs and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, representing a major public health challenge.3,4 Hydroxyurea (HU) has been successfully used in the treatment of β-hemoglobinopathies by augmenting the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Increased levels of HbF both interfere with sickle hemoglobin (HbS) polymerization (thereby preventing red blood cells from sickling in sickle cell disease) and reduce the α-globin chain imbalance in β-thalassemia.5-8 The molecular mechanisms underlying HU-mediated γ-globin induction remain to be fully defined. Several signal transduction pathways have been shown to be related to HU-regulated γ-globin expression, including modulation of soluble guanylate cyclase, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, and guanosine monophosphate,9 increased nitric oxide production,9,10 regulation of GATA-1 and GATA-2,11,12 activation of stress molecules,13 and modulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk)/p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/Jun.14-19 It has also been demonstrated that HU induces c-Jun expression at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels and blocks erythroid differentiation.20

In an effort to further elucidate and unify the molecular mechanisms by which HU regulates HbF production, we previously identified an HU-induced small guanosine triphosphate-binding protein, named secretion-associated and ras-related protein (SAR1), in human adult erythroid cells and demonstrated its function in HbF production.15 The function of SAR1 in vesicle budding has been extensively characterized in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but less studied in mammals.21 During erythropoiesis, SAR1 has been reported to be increasingly expressed in erythropoietin-stimulated cultures and could be further induced with additional HU treatment.22,23 There are 2 SAR1-related genes, SAR1A and SAR1B, found in mammals, including humans.22 Mutations in the SAR1B gene appear to induce lipid absorption disorders, such as Anderson disease, which may be accompanied by hematologic symptoms, including anemia.24 We and others have reported that SAR1 significantly increased γ-globin expression in primary CD34+ cells,15 and that variations within SAR1 regulatory elements might contribute to differences among individuals in regulation of HbF expression and in response to HU in sickle cell disease patients.25,26 These observations suggest that SAR1 plays a crucial role in HbF expression.

In this study, we dissected the SAR1 promoter region and identified an Elk-1/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) binding site responsible for HU-mediated SAR1 gene induction. We found that SAR1 is prerequisite for the major effects of HU on HbF induction in 2 distinct models of human erythroid differentiation: a transformed red cell line (K562 cells) and ex vivo human hematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+ cells). HU-induced SAR1 expression activated γ-globin expression predominantly through the Giα/JNK/Jun pathway, which may provide a novel target for therapeutic intervention aimed at upregulating γ-globin gene expression in hemoglobinopathies.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

Bone marrow CD34+ cells (LONZA) and K562 (ATCC) cells were cultured as previously described.27 On day 5 of differentiation, SAR1-expressing vector or empty vector was electrophoresed into CD34+ cells using the LONZA 4D-Nucleofector system according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SAR1-V5 tag– or vector only–stably transfected K562 cells were established according to a previously published protocol.15

Cloning of SAR1 promoter region and reporter gene assays

SAR1 promoter fragments were cloned from K562 genomic DNA using the GC-RICH PCR system (Roche) and inserted into the pGL3 basic luciferase vector (Promega). All mutant reporter gene constructs were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). Plasmids were sequenced to verify the integrity of the insert. The level of promoter activity was evaluated by measurement of firefly luciferase activity relative to the internal control Renilla luciferase activity using the Dual Luciferase Assay system (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. K562 cells or CD34+ cells were preincubated with HU for 2 days, then cotransfected with a reporter construct, and a pRL-TK vector that produces Renilla luciferase (Promega). The transfected cells were continually treated with or without HU for another 12 to 48 hours.

EMSAs, antibody-supershift assays, and ChIP assays

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and antibody-supershift assays were performed according to a previously described protocol.28 Sequences for each probe were as follows: wild-type Elk-1/NF-κB, 5′-ACGCGCCCGGAAGTCCCGGGG-3′; mutant Elk-1/NF-κB, 5′-ACGCGCTAGCGCGTGACGGGG-3′. Two micrograms of anti-NF-κB p50, anti-Elk-1, anti-c-Rel, or rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used in supershift assays. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as previously described.27

RNAi assays

A plasmid-based system for production of SAR1 microRNA (miR) interfering RNA (RNAi) (5′-TGCTGTAACCTTGCCTCTTGAGCACAGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACTGTGCTCAAGGCAAGGTTACAGG-3′) or negative control miR RNAi was generated by inserting oligonucleotides into pcDNATM6.2-GW/miR (Invitrogen). Five micrograms of miR RNAi or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was transfected into K562 cells using the Nucleofector system (Amaxa Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s optimized protocol. K562 cells were transfected with control or SAR1 miR RNAi twice (on day 0 and day 1) followed by 3 days of HU treatment (day 0 to day 2), then subjected to flow cytometry to detect HbF-positive cells. For shRNA-mediated SAR1 silencing, K562 cells were incubated with or without HU for 2 days after transfected with SAR1 shRNA or control shRNA, then subjected to 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay or terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay.

CD34+ bone marrow cells were infected by SAR1 shRNA or control shRNA lentivirus (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at day 4 of expansion. On day 6, transduced CD34+ cells were reseeded and grown in differentiation medium with 2 µg/mL puromycin for 14 days. At day 7 of differentiation, cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-HbF antibody, and subjected to flow cytometry to detect HbF-positive cells. At day 10 of differentiation, transduced CD34+ cells were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography analysis for measurement of HbF, Giemsa staining for morphologic changes, and flow cytometry for CD71/glycophorin A (GPA) expression.

For Giα silencing experiments, CD34+ cells were cotransfected with SAR1-expressing vector or empty vector and scrambled siRNA or Giα siRNA, and the transfected cells grown in differentiation medium for 2 days before being harvested for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and western blot analysis.

Coimmunoprecipitation

For coimmunoprecipitation studies, 1 mg of whole-cell lysates from K562 cells stably transfected with SAR1-V5 tag or control vector was incubated with 2 μg/mL anti-Giα1, -Giα2, -Giα3, -Gαq, or -Gβ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 3 hours at 4°C. Recombinant Protein G-Sepharose 4B (20 μL; Invitrogen) was then added and gently mixed overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed 3 times with immunoprecipitation buffer and boiled in 35 μL of sample-loading buffer (NuPAGE LDS sample buffer; Invitrogen) for 10 minutes. After a brief spin to remove the protein G-Sepharose beads, the supernatant (25 μL) was run in a 4% to 12% Bis-Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) gel (Invitrogen) for western blot analysis with anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed using the Student t test for significance of the difference of individual pairs and the Pearson correlation coefficient for the closeness of linear relationship.

Results

Basal and HU-mediated SAR1 transcriptional regulation requires an intact Elk-1/NF-κB–binding site in the SAR1 promoter

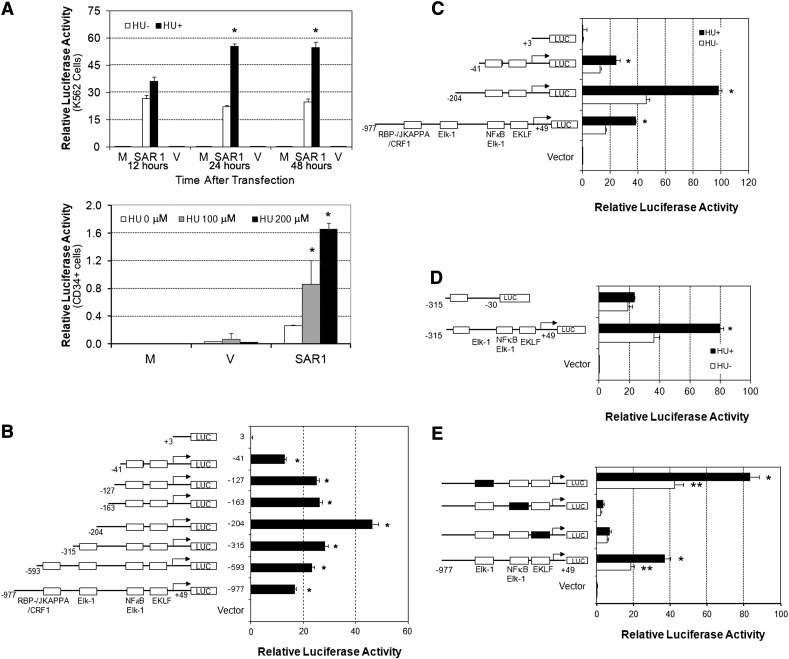

Our prior work has demonstrated that the SAR1 gene, which we cloned from primary cultures of human adult erythroid cells, was inducible by HU treatment and upregulated γ-globin expression in K562 and CD34+ cells.15 This finding led us to investigate how SAR1 is transcriptionally regulated by identifying the promoter elements responsible for SAR1 induction by HU. When we examined the proximal region of the SAR1 promoter sequence based on MatInspector software, we found putative-binding sites for several transcription factors, such as EKLF, Elk-1, and NF-κB. The promoter region contains 1 binding consensus site for both Elk-1 and NF-κB (supplemental Figure 1, available at the Blood Web site). A series of recombinant DNA plasmids containing various lengths of the predicted SAR1 promoter sequence (−977 to +49) in a luciferase reporter vector was prepared and transfected into K562 cells or CD34+ cells at day 6 of differentiation with or without 2 days of HU pretreatment. We found that 24 or 48 hours after transfection, reporter activity was significantly increased in HU-treated K562 cells transfected with the full-length SAR1 reporter construct compared with nontreated controls (Figure 1A, top panel). HU treatment also increased SAR1 promoter activity in CD34+ cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A, bottom panel). Deletion analysis revealed that the reporter construct containing the −41 to +49 region produced a high luciferase activity (Figure 1B) while retaining most of the HU-mediated induction of SAR1 promoter activity (Figure 1C). In contrast, the luciferase activity generated from the reporter construct containing the +3 to +49 fragment dropped to the level of the vector control (Figure 1B), and its luciferase activity could not be increased by HU (Figure 1C). Moreover, removal of the −30 to +49 fragment in the reporter construct containing the −315 to +49 region not only decreased luciferase activity, but also eliminated the HU-responsive luciferase activity (Figure 1D). These results imply that an element within the region between −41 and +3 is sufficient to drive SAR1 promoter activity and is responsible for HU-mediated SAR1 induction.

Figure 1.

The 5′-region of the SAR1 gene exhibits promoter activity that is inducible by HU and contains intact Elk-1/NF-κB–binding sites that are required for basal and HU-induced SAR1 promoter activity. (A) Top panel, −977 to +49 genomic region containing the predicted promoter region was cloned into the pGL3 basic luciferase vector and transfected into K562 cells with (+) or without (−) 2 days of 100 μM HU pretreatment. The level of promoter activity in K562 cells was evaluated 12, 24, and 48 hours after transfection. Bottom panel, SAR1 reporter construct was transfected into CD34+ cells with 2 days of 0, 100, or 200μM HU pretreatment at day 6 of differentiation. The level of promoter activity in CD34+ cells was evaluated 24 hours after transfection. Mock-, SAR1 reporter construct–, and vector control–transfected cells are indicated as M, SAR1, and V, respectively. *P < .05 vs HU untreated cells. (B) Deletions of the SAR1 promoter region were constructed and transfected into K562 cells, then promoter activity measured 24 hours after transfection. Left side, Schematic diagram of deletions with transcription factor–binding sites indicated. *P < .001 vs vector control–transfected cells. (C-D) Reporter constructs containing different fragments of the SAR1 promoter were transfected into K562 cells with (+) or without (−) 2 days of 100 μM HU pretreatment. Left side, Schematic diagram of deletion constructs. Luciferase activities were measured 24 hours after transfection. *P < .05 vs HU untreated cells. (E) Mutation analysis of the effects of Elk-1, EKLF, and Elk-1/NF-κB transcription factor binding sites on SAR1 promoter activity. Left side, Schematic diagram of wild-type and mutant reporter constructs. Luciferase activities were measured 24 hours after transfection into K562 cells with (+) or without (−) 2 days of 100 μM HU pretreatment. □, Wild-type transcription factor–binding sites; ▪, mutated transcription factor–binding sites. **P < .001 vs vector control–transfected cells without HU treatment; *P < .05 vs HU untreated cells. The level of promoter activity was evaluated by measurement of the firefly luciferase activity relative to the internal control Renilla luciferase activity using the Dual Luciferase Assay system. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. SD, standard deviation.

To determine which regulatory elements were involved in SAR1 gene transcription and HU responsiveness, we introduced mutations in the binding sites for Elk-1, EKLF, or Elk-1/NF-κB. We found that mutations at either the EKLF or Elk-1/NF-κB sites significantly decreased SAR1 promoter activity and abolished its responsiveness to HU treatment, and alteration of the Elk-1–binding site increased luciferase activity without compromising HU-induced SAR1 promoter activity (Figure 1E). These results suggest that these EKLF and Elk-1/NF-κB–binding sites are important for SAR1 transcription and HU-regulated SAR1 induction, and the Elk-1–binding site is a functional element that negatively regulates SAR1 gene expression.

Transcription factor NF-κB binds to its cognate site in the SAR1 5′-upstream region

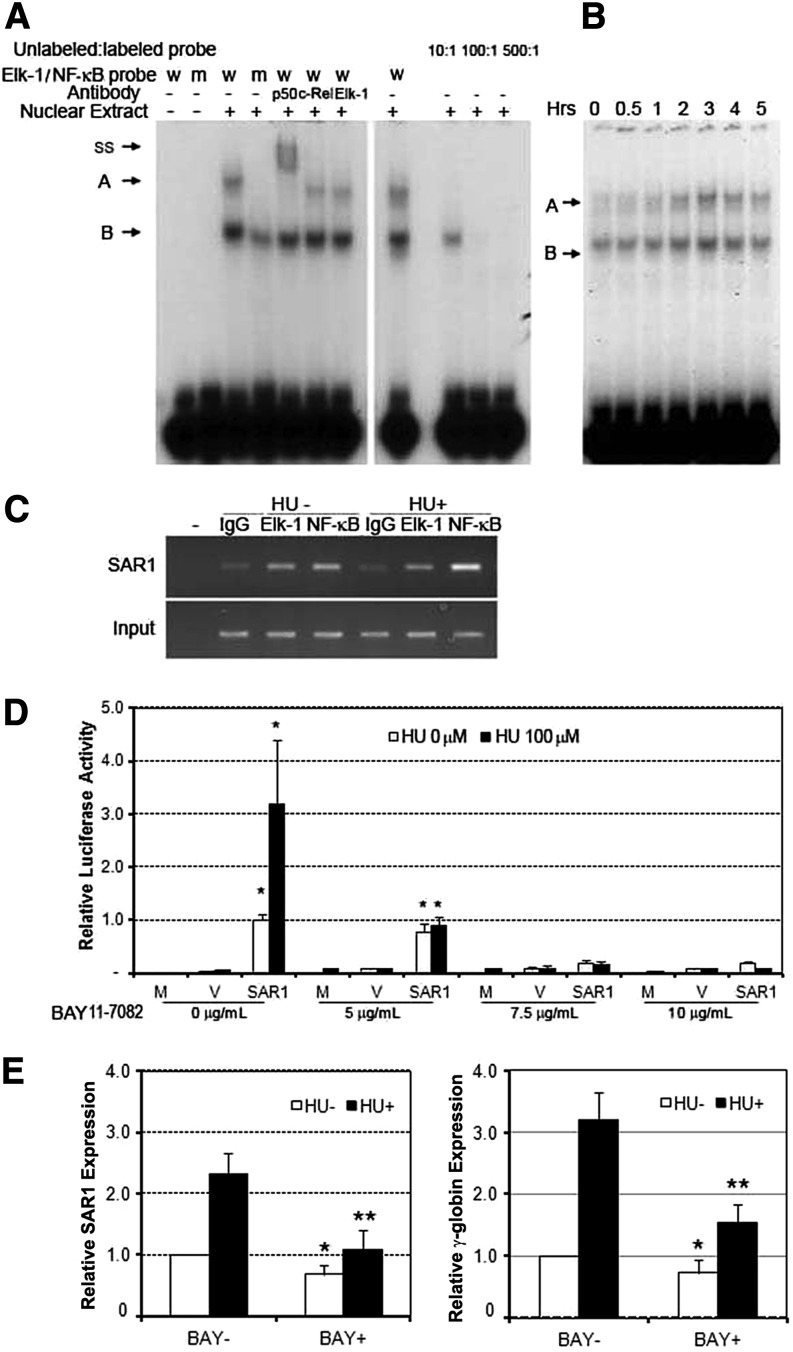

To determine whether these promoter sequences were indeed recognized by their putative transcription factors, we performed EMSAs using 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the Elk-1/NF-κB consensus sequence and its corresponding mutant. When nuclear extracts from K562 cells were incubated with the wild-type radiolabeled DNA probe, 2 shift bands of specific protein-DNA complexes were detected (Figure 2A, left panel, complexes A, B). When the Elk-1/NF-κB mutant probe was used, band A was clearly absent and the density of band B was substantially reduced. The gel-shift signal could be efficiently competed by unlabeled oligonucleotides containing the wild-type sequence (Figure 2A, right panel). These data indicate that the putative Elk-1/NF-κB–binding site is responsible for the formation of the 2 complexes. Antibody-supershift assays were used to further confirm the binding of the transcription factors to their recognition sites on the SAR1 promoter. Addition of NF-κB p50 antibodies, but not Elk-1 or c-Rel antibodies, eliminated band A and resulted in a new higher molecular weight band termed “ss” (Figure 2A, left panel). These data suggest that the band “A” protein complex is composed of NF-κB p50 protein that may activate SAR1 transcription through binding to specific sites in the SAR1 5′-upstream region. Similar experiments were not able to confirm the specific binding of the transcription factors EKLF and Elk-1 with their recognition sites (data not shown).

Figure 2.

HU activates NF-κB signaling and enhances NF-κB binding to the SAR1 promoter region. (A) EMSA for the Elk-1/NF-κB was performed using K562 nuclear extracts (10 μg) and oligonucleotide probes containing either a wild-type or mutant Elk-1/NF-κB–binding site. Competition analysis was performed in the presence of 10-, 100-, or 500-fold excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides (right panel). Antibody-supershift assays were performed using antibodies against NF-κB p50, c-Rel, and Elk-1. Two Elk-1/NF-κB–specific DNA-protein complexes are indicated as A and B. The DNA-protein complex supershifted by anti-NF-κB p50 antibody is indicated as ss. (B) EMSA analysis of the effects of HU on NF-κB binding to its recognition site in the SAR1 promoter. EMSA was performed using nuclear extracts (10 μg) isolated from K562 cells treated with 100μM HU for the indicated period and oligonucleotide probes containing the Elk-1/NF-κB–binding site. A and B represent Elk-1/NF-κB–specific DNA-protein complexes as described in A. (C) At day 6 of differentiation, CD34+ cells were treated with or without 100 µM HU. Cells were then harvested and subjected to ChIP assay using antibody against NF-κB or Elk-1 to immunoprecipitate chromatin-protein complexes. A parallel ChIP assay was performed using rabbit IgG for the immunoprecipitation step as a ChIP assay negative control. DNA was amplified and quantitated by PCR with specific primers flanking the SAR1 gene promoter from −137 to −12. (D) CD34+ cells were treated in the presence or absence of 100 μM HU from day 4 to day 7 of differentiation, and preincubated in medium with 0, 5, 7.5, or 10 μg/mL BAY11-7082 for 30 minutes at day 6, transfected with a construct containing the −977 to +49 region of the SAR1 gene, then assayed for luciferase activity 24 hours after transfection. *P < .05 vs mock-transfected cells without treatment. Mock-, SAR1 reporter construct–, and vector control–transfected cells are indicated as M, SAR1, and V, respectively. The level of promoter activity was evaluated by measurement of the firefly luciferase activity relative to the internal control Renilla luciferase activity using the Dual Luciferase Assay system. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. (E) At day 5 of differentiation, CD34+ cells were treated with or without 4 μg/mL BAY11-7082 in the presence or absence of 100 µM HU for 3 days, then harvested and measured for SAR1 (left panel) and γ-globin (right panel) expression by real-time PCR analysis. Fold increase was calculated relative to expression in cells without BAY11-7082 and HU treatment after normalization with β-actin gene expression. *P < .01 vs CD34+ cells without BAY11-7082 and HU treatment. **P < .01 vs CD34+ cells with HU treatment only. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. m, mutant; w, wild-type.

HU activates NF-κB signaling and enhances NF-κB binding to the SAR1 promoter region

We next set out to explore the effect of HU on NF-κB signaling and binding of NF-κB to the SAR1 promoter region. Immunofluorescence staining with an Alexa Fluor–conjugated NF-κB p50 antibody showed that HU substantially increased nuclear localization of NF-κB in CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 2A). Western blot analysis revealed that HU treatment induced phosphorylation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB, and increased levels of nuclear NF-κB p50 protein in a time-dependent manner in K562 cells. The effects peaked at 3 hours post-HU treatment and then gradually declined (supplemental Figure 2B). A similar pattern was observed from EMSA analysis showing that HU enhanced the binding of NF-κB to its cognate site within the SAR1 promoter region (Figure 2B).

To test whether Elk-1 or NF-κB directly binds the regulatory regions of the SAR1 gene promoter in primary cells, we performed ChIP assays in CD34+ cells with or without HU treatment. ChIP data indicated that NF-κB antibody immunoprecipitated the SAR1 promoter region, and that HU treatment enhanced NF-κB binding to the promoter. Surprisingly, although Elk-1 could directly bind the SAR1 promoter region, HU treatment did not augment the binding (Figure 2C). To provide further evidence that NF-κB is a key transcriptional regulator for SAR1 promoter activity and that HU influences the activity through recruitment of NF-κB to the gene promoter, CD34+ cells were preincubated with the NF-κB–specific inhibitor BAY11-7082, transfected with SAR1 reporter construct, then tested for luciferase activity in the absence or presence of HU treatment. Blocking NF-κB activation by BAY11-7082 in CD34+ cells produced a dose-dependent downregulation of SAR1 promoter activity and blocked HU-mediated SAR1 promoter activity (Figure 2D). Furthermore, BAY11-7082 also significantly reduced basal and HU-induced SAR1 and γ-globin expression in CD34+ cells (Figure 2E). The NF-κB inhibitor had a more profound effect on HU-responsive SAR1 and γ-globin expression than on basal levels. Taken together, our results indicate that HU treatment upregulated SAR1 transcription through the NF-κB pathway by causing NF-κB to translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and subsequently bind to its recognition site in the SAR1 promoter.

Overexpression of SAR1 enhances HbF production in K562 and CD34+ cells

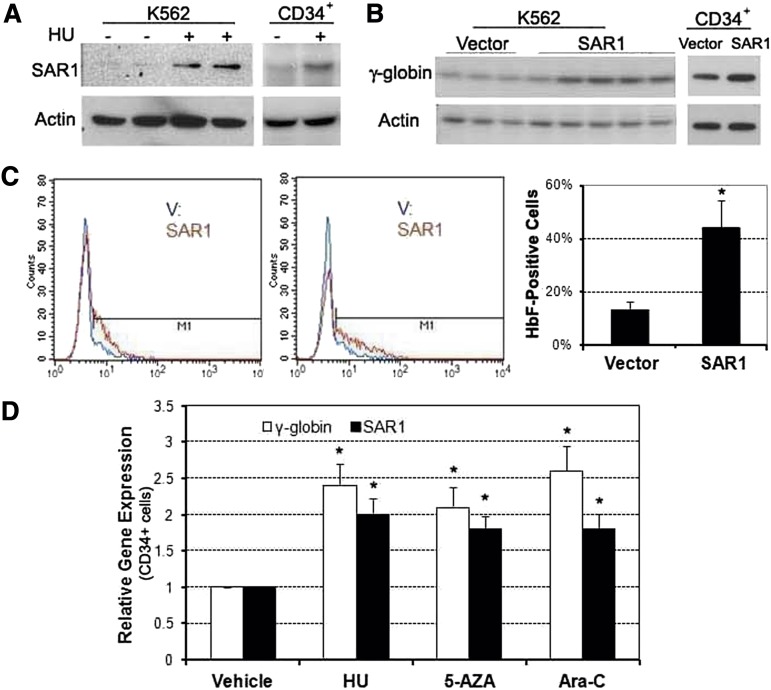

We previously demonstrated that HU induced SAR1, and that overexpression of SAR1 increased γ-globin at the transcriptional level in K562 cells and primary cultures of CD34+ cells.15 Here we furthered those studies by examining HU’s effects at the protein level. HU was found to increase SAR1 protein expression (Figure 3A), and overexpression of SAR1 increased levels of γ-globin chain protein (Figure 3B). SAR1 overexpression also significantly increased the percentage of HbF-positive cells from a mean of 14% to 44% in K562 cells (Figure 3C). We also found that various hemoglobin gene inducers (HU, 5-azacytidine, and Ara-C) could increase γ-globin messenger RNA (mRNA) expression with a concomitant increase of SAR1 mRNA levels in primary CD34+ cells after 72 hours of drug exposure (Figure 3D). These data and our previously published results15 strongly support the role of SAR1 in the transcriptional regulation of γ-globin expression.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of SAR1 enhances HbF production in K562 and CD34+ cells. (A) Western blot analysis of SAR1 protein expression in K562 and CD34+ cells after 3 days of 100 µM HU treatment. CD34+ cells were treated with HU at day 5 of differentiation. (B) Western blot analysis of γ-globin expression in SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells and SAR1- or vector control–transfected CD34+ cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-HbF antibody, then subjected to flow cytometry to detect HbF-positive cells. Left panels, 2 representative flow cytometry results. Right panel, graphical representations of flow cytometry data for HbF protein expression in SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells. *P < .05 vs vector control–transfected cells. Error bars represent SD of the mean of >3 independent experiments. (D) Real-time PCR analysis of γ-globin and SAR1 expression in CD34+ cells treated with HU, 5-AZA, or Ara-C for 72 hours on day 6 of differentiation. The vehicle-treated value was set to 1.0 and fold increase was calculated relative to expression in vehicle-treated cells after normalization to β-actin gene expression. *P < .05 vs vehicle-treated cells. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. 5-AZA, 5-azacytidine.

Silencing SAR1 expression in K562 and CD34+ cells reduces basal and HU-induced ΗbF production

To further confirm that basal and HU-induced HbF expression is mediated through SAR1, we silenced the expression of SAR1 in K562 and CD34+ cells by RNAi targeting SAR1 and then measured HbF production by flow cytometry. Silencing of SAR1 in K562 cells using SAR1 miR RNAi (knockdown efficiency shown in supplemental Figure 4A) reduced basal and HU-mediated HbF expression by 22% and 35%, respectively, compared with mock-transfected cells (Figure 4A). Similar results were obtained when CD34+ cells were transduced with lentiviruses containing SAR1 shRNA to silence SAR1 expression (knockdown efficiency shown in supplemental Figure 3D). In SAR1-knockdown CD34+ cells, basal and HU-induced HbF levels were reduced by 23% and 38%, respectively, compared with control shRNA-transduced cells at day 7 of differentiation (Figure 4B). shRNA-mediated knockdown of SAR1 in CD34+ cells resulted in a 74% decrease in HbF levels (from 5.1% ± 1.4% to 1.3% ± 0.6%, P < .05), with no notable changes in cell morphology and surface expression of GPA/CD71 markers at day 10 of differentiation (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Our findings indicate that SAR1 is an obligatory mediator in HU-induced HbF production, although SAR1 might not be the exclusive mediator of HbF induction by HU.

Figure 4.

Silencing SAR1 expression reduces HbF protein expression in K562 and CD34+ cells and attenuates HU-mediated S-phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. (A) K562 cells were transfected with SAR1 miR RNAi or control miR RNAi at day 0 and day 1, and incubated with or without 100 μM HU for 3 days after transfection at day 0. Cells were harvested, stained with PE-conjugated anti-HbF antibody, and subjected to flow cytometry to detect HbF-positive cells. (B) CD34+ bone marrow cells were infected by SAR1 shRNA or control shRNA lentivirus at day 4 of expansion. On day 6, transduced CD34+ cells were reseeded and grown in differentiation medium with 2 µg/mL puromycin for 7 days. Cells were harvested, stained with PE-conjugated anti-HbF antibody, and subjected to flow cytometry to detect HbF-positive cells. Left panels, representative flow cytometry results. Right panels, graphical representation of flow cytometry data for HbF protein expression with or without HU treatment relative to that of mock-transfected (A) or control shRNA lentivirus-transduced (B) cells not treated with HU. (C-D) K562 cells were incubated with or without HU for 2 days after transfection with SAR1 shRNA or control shRNA, then subjected to cell-cycle analysis using a BrdU incorporation assay or TUNEL assays. (C) Panels display representative BrdU incorporation assay results; the mean (±SD) percentage of cells in S-phase is shown below. (D) Apoptotic cells were stained green (GFP) in TUNEL assay; the nuclei of cells were stained blue with DAPI. Left panel, representative TUNEL assay results. Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope system (Axioplan 2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) with a 20×/0.75 NA objective and a Zeiss Axiocam HRc real-color CCD camera and AxioVision 4 (Zeiss) acquisition software. Right panel, graphical representation of TUNEL assay results showing percent of GFP-positive cells. *P < .05 vs control-transfected cells not treated with HU. **P < .05 vs control-transfected cells with HU treatment. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Silencing SAR1 expression attenuates HU-mediated S-phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis

We have previously shown that SAR1 overexpression alone can replicate the known effects of HU in 2 human erythroid differentiation models, including cell-cycle regulation and cytotoxicity.15 Therefore, if HU inhibits erythroid cell growth through induction of SAR1, one would expect that suppression of SAR1 expression would reverse HU-induced inhibitory effects. Transfection of K562 cells with SAR1 shRNA (knockdown efficiency shown in supplemental Figure 4B) had no notable effect on the cell cycle in untreated cells, but significantly attenuated HU-mediated S-phase cell-cycle arrest in SAR1-knockdown cells. The percentage of S-phase cells was 68%, compared with 83% in control shRNA-knockdown cells (P < .01), as determined by BrdU incorporation assay (Figure 4C). In TUNEL assays, knockdown of SAR1 did not change basal apoptosis levels, but did significantly abolish HU-mediated apoptosis in K562 cells (Figure 4D). These results indicate that HU-induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis are mediated, at least in part, through alteration of SAR1 expression.

SAR1 enhances HbF expression through the activation of JNK/Jun signaling

To further investigate the mechanism underlying SAR1-regulated HbF expression, we first knocked down SAR1 expression in CD34+ cells and examined its effects on expression of other known γ-globin regulators, such as BCL11A, MYB, and EKLF.29-32 Our real-time PCR analysis showed that silencing of SAR1 expression in CD34+ cells upregulated BCL11A expression by 60%, but caused no significant changes in MYB and EKLF mRNA levels, as compared with control shRNA-transduced CD34+ cells at day 7 of differentiation (supplemental Figure 3E). In addition, the moderate increase of BCL11A mRNA levels did not translate into an increase of protein levels when SAR1-knockdown CD34+ cells were examined by western blot analysis (data not shown).

SAR1 is known to function in protein trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi via the cytosolic coat protein complex II (COPII) secretory pathway. We examined whether the COPII pathway could account for the HU-induced enhancement of γ-globin production and found that genetic silencing of the COPII component Sec12/Sec23 or chemical inhibition of vesicle protein transport from ER to Golgi with brefeldin A could only partially affect HU-induced γ-globin expression without a change in basal γ-globin level (supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that SAR1 might also use other signal transduction pathways to regulate hemoglobin expression in the context of HU treatment.

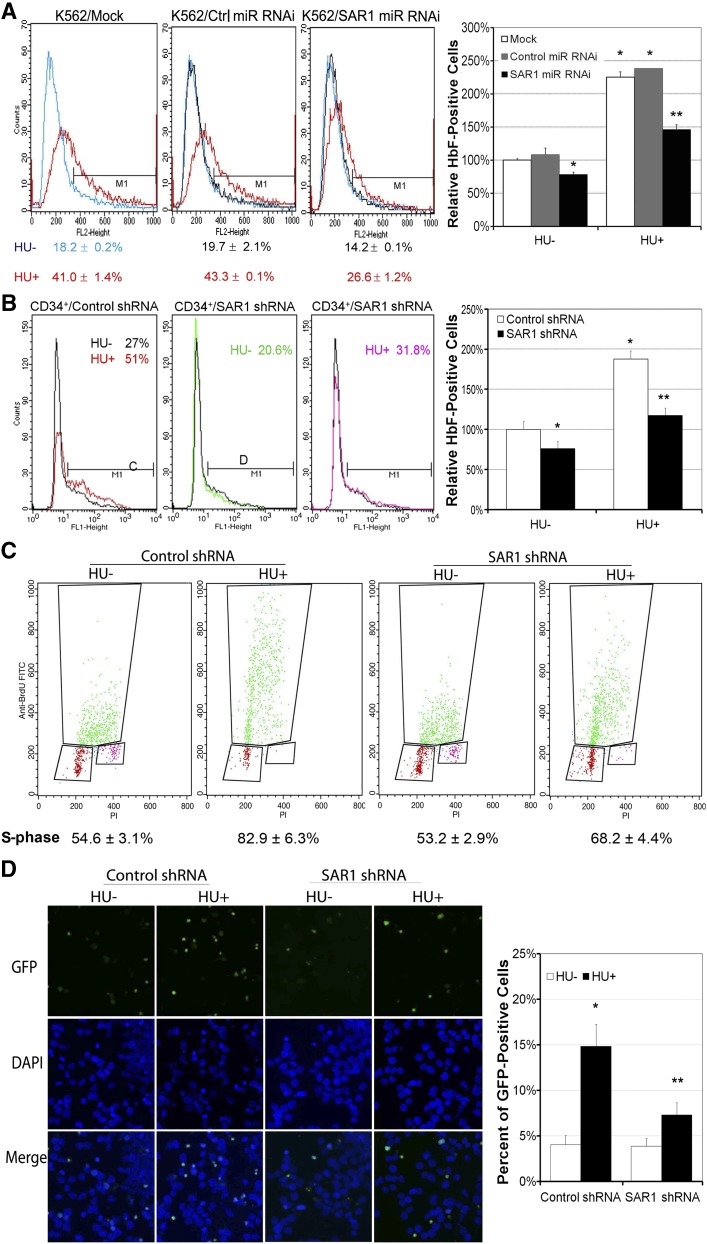

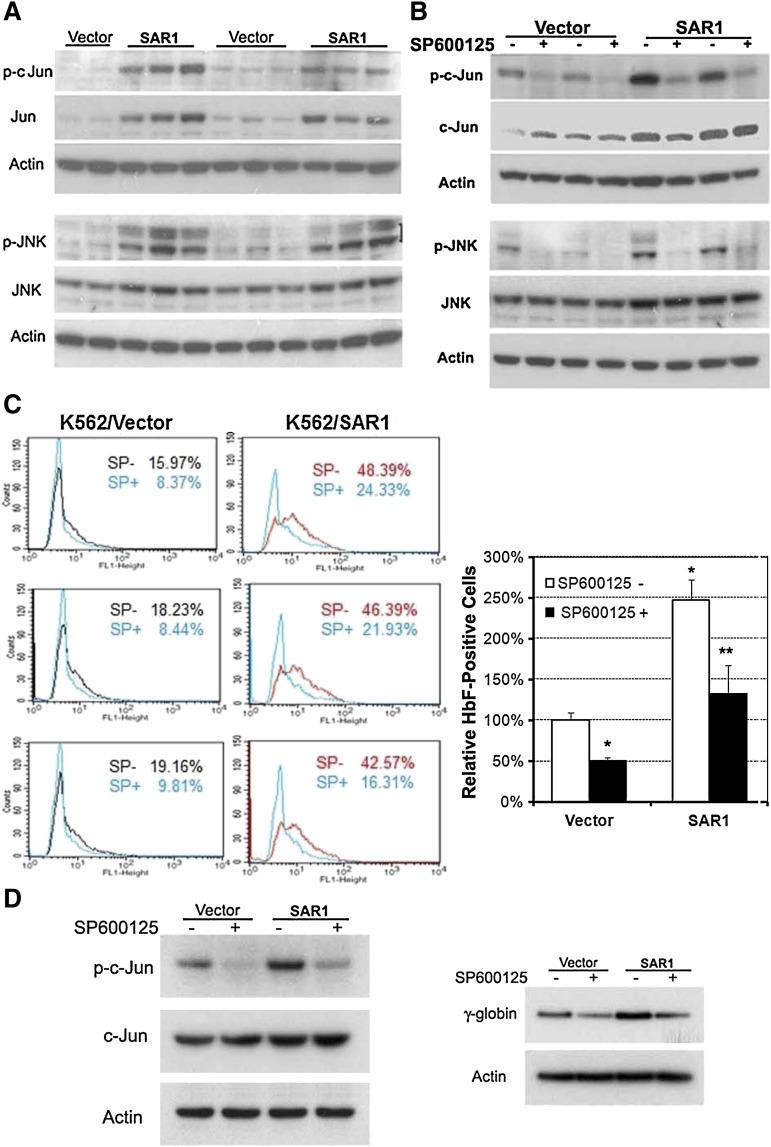

To determine the possible signaling cascade involved in SAR1-mediated HbF induction, PowerBlots and micro-western blots were carried out to search for potential candidates. Both approaches indicated that SAR1 increased Jun expression in SAR1-stably transfected K562 cells (data not shown). We confirmed these results by western blot analysis, which revealed that overexpression of SAR1 markedly increased both total and phosphorylated c-Jun, as well as induced phosphorylation of its upstream signaling molecule JNK (Figure 5A). To verify that JNK/Jun signaling accounts for the functionality of SAR1 in upregulating HbF expression, vector control– and SAR1-stably transfected K562 cells were incubated with the JNK phosphorylation inhibitor SP600125 for 5 days, then assessed for Jun activation and HbF expression. SP600125 substantially suppressed basal and SAR1-regulated Jun and JNK phosphorylation (Figure 5B), which was accompanied by a significant reduction in the percentage of HbF-positive cells in vector control– and SAR1-stably transfected K562 cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

SAR1 enhances HbF expression through the activation of JNK/Jun signaling. (A) Western blot analysis of SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells for expression of phospho- and total c-Jun and phospho- and total JNK. (B) Western blot analysis of SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells for expression of phospho- and total c-Jun and phospho- and total JNK after incubation in the absence or presence of the JNK phosphorylation inhibitor SP600125 (12.5 μM) for 5 days. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells incubated in the absence or presence of SP600125 (12.5 μM) for 5 days were stained with PE-conjugated anti-HbF antibody and subjected to flow cytometry for measurement of HbF-positive cells. Left panels, representative flow cytometry results. Right panel, Graphical representation of flow cytometry data for HbF protein expression in SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells with or without SP600125 treatment. *P < .001 vs vector control–transfected cells without SP600125 treatment, **P < .001 vs SAR1-transfected cells without SP600125 treatment. Error bars represent SD of the mean of >3 independent experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of SAR1- or vector control–transfected CD34+ cells for expression of phospho- and total c-Jun (left panel) and γ-globin chain (right panel) after incubation in the presence or absence of SP600125 (20 µM) for 3 days. β-actin was used as a loading control. CD34+ cells were transfected at day 5 of differentiation.

Given that K562 cells are genetically abnormal, we extended our studies to the more clinically relevant CD34+ cells to examine the effect of Jun signaling on SAR1-regulated γ-globin expression. SAR1- and vector control–transfected CD34+ cells were incubated with or without SP600125. SP600125 markedly inhibited Jun phosphorylation and γ-globin expression in both SAR1- and vector control–transfected CD34+ cells (Figure 5D). These results clearly demonstrate that JNK/Jun signaling plays a pivotal role in basal and SAR1-regulated HbF expression.

Exogenously expressed SAR1 binds to Giα2, 3 proteins to activate Jun and increase γ-globin chain in K562 and CD34+ cells

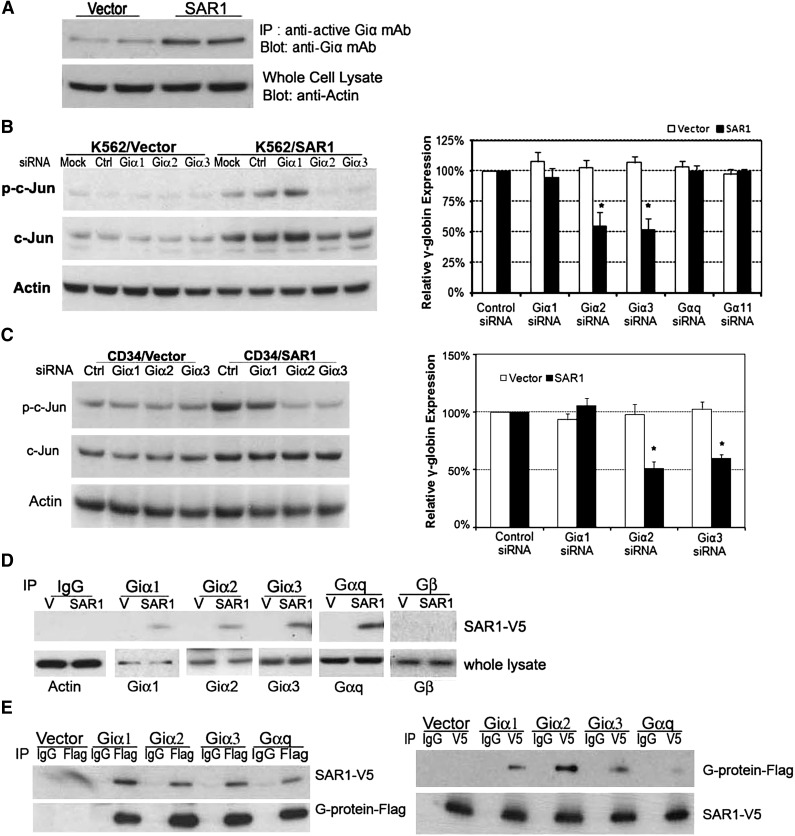

Several lines of evidence have indicated that activation of Jun and heterotrimeric G-proteins, especially Giα2 and Giα3 proteins, are associated with erythroid cell differentiation and γ-globin expression.17,18,33-37 We postulated that SAR1 might activate the JNK/Jun pathway to regulate γ-globin expression through crosstalk between heterotrimeric G-protein and small G-protein.38 To this end, we examined whether SAR1 can regulate Giα activity and what roles Giα played in SAR1-mediated Jun activation and γ-globin induction. Giα activation assays showed that transfection of SAR1 increased the levels of Giα activation (Figure 6A). Knockdown of Giα2 or Giα3, but not of Giα1, in SAR1-stably transfected K562 cells or SAR1-transfected CD34+ cells (knockdown efficiencies shown in supplemental Figures 6-7) substantially reduced SAR1-stimulated c-Jun phosphorylation and was accompanied by a decreased γ-globin expression by approximately one-half compared with silencing control (Figure 6B-C). We also found that silencing of Gαq or Gα11 had no significant impact on γ-globin expression in K562 cells. These data support our hypothesis that SAR1 promotes γ-globin expression through the Giα/Jun signal pathway.

Figure 6.

Exogenously expressed SAR1 binds to Giα2, 3 proteins to activate Jun and increase γ-globin chain in K562 and CD34+ cells. (A) SAR1- or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells were subjected to Giα activation assay. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) SAR1- or vector only–stably transfected K562 cells were transfected with control, Giα1, Giα2, Giα3, Gαq, or Gα11 siRNA at day 0 and day 1, then collected at day 3 for western blot analysis to examine phospho- and total c-Jun protein expression (left panel) and real-time PCR to analyze γ-globin mRNA expression (right panel). Mock-transfected cells were used as a negative control. β-actin was used as a loading control. Fold increase was calculated relative to expression in corresponding control siRNA-transfected cells after normalization with β-actin gene expression. *P < .001 vs SAR1-overexpressed K562 cells transfected with control siRNA. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. (C) CD34+ cells were cotransfected with SAR1-expressing or empty vector and scrambled siRNA or Giα1, Giα2, or Giα3 siRNA at day 5 of differentiation, then collected at day 7 for western blot analysis to examine phospho- and total c-Jun protein expression (left panel) and real-time PCR to analyze γ-globin chain mRNA expression (right panel). Fold increase was calculated relative to expression in corresponding control siRNA-transfected cells after normalization with β-actin gene expression. *P < .001 vs CD34+ cells transfected with SAR1 and control siRNA. Error bars represent SD of the mean of 3 independent experiments. (D) Whole-cell lysates from SAR1-V5– or vector control–stably transfected K562 cells were immunoprecipitated with normal IgG, anti-Giα1, -Giα2, -Giα3, -Gαq, or -Gβ antibody, then the immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot analysis with anti-V5 antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) SAR1-V5–stably transfected K562 cells were transfected with vector only, Giα1-Flag, Giα2-Flag, Giα3-Flag, or Gαq-Flag. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag or anti-V5 tag antibody, and the immunoprecipitates subjected to western blot analysis with anti-V5 or anti-Flag antibody, respectively.

Next, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation study with vector control– or SAR1-stably transfected K562 cells to test whether SAR1 could directly associate with Giα proteins. Exogenously expressed SAR1-V5 could be coimmunoprecipitated when using a precipitating antibody to endogenous Giα1, 2, 3, or Gαq, but not with antibody to Gβ protein (Figure 6D). Because the Giα antibodies were not sensitive enough to detect their relative G-proteins in the lysates precipitated by anti-V5 antibody, we opted to transfect SAR1-V5–stably expressing K562 cells with vectors containing Flag-tagged Giα1, 2, 3, or Gαq for reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation. Thus, detection of anti-V5 antibody coimmunoprecipitated proteins could be achieved by the use of anti-Flag antibody in western blot analyses. Using this approach, we found that SAR1-V5 could be coimmunoprecipitated with an antibody recognizing Flag-Giα1, 2, 3, or Gαq, and vice versa (Figure 6E). We found similar binding in 293T cells when cells were cotransfected with SAR1-V5 and Giα1, 2, 3 or Gαq-Flag (data not shown). Taken together, we concluded that exogenous expression of SAR1 may activate Jun to increase HbF expression in K562 cells via interaction with Giα2 and Giα3 proteins.

Discussion

Our previous studies identified SAR1 as an HU-inducible gene and demonstrated a novel role for this small guanosine triphosphate–binding protein in both cell-cycle control and hemoglobin gene expression regulation in K562 and CD34+ cells.15 Based on these unique functions of SAR1, it is important to identify the regulatory elements in the SAR1 gene promoter region and its cognate DNA-binding proteins that confer HU inducibility, to assess whether SAR1 is an obligatory mediator of these functions, and to elucidate the molecular events underlying SAR1-regulated HbF expression. In the present study, we first dissected the SAR1 promoter region and identified the binding site for the transcription factors Elk-1/NF-κB required for HU-mediated SAR1 gene induction. We then demonstrated that SAR1 is necessary and central to the beneficial effects of HU treatment through its induction of HbF. More importantly, we discovered that forcibly expressed SAR1 interacts with Giα proteins to activate the Giα/JNK/Jun pathway and increase HbF expression in the transformed red cell line K562 and ex vivo human hematopoietic progenitor CD34+ cells.

Recently, a new cell-stress signaling model was suggested to be a common pathway for HbF induction.13 Along with other HbF-inducing agents, the replication stress inducer HU has been identified as a potent HbF inducer through its effects in stimulating γ-globin production during adult erythropoiesis by way of activating cell-stress signaling. The function of NF-κB in hemoglobin regulation has been indicated in several previous studies.39-42 Through regulation of its target genes, NF-κB functions as a key modulator of the cellular response to physiological and pathological stress conditions. In this study, the physical and specific interaction between NF-κB and the SAR1 promoter was verified by EMSAs, antibody-supershift assays, and ChIP assays in K562 or CD34+ cells. In addition, mutation of the putative NF-κB–binding site in the SAR1 promoter and inhibition of NF-κB activation by pharmacologic intervention significantly impaired basal and HU-mediated SAR1 and γ-globin transcription. These data, together with our finding that HU induced ataxia-telangiectasia mutated phosphorylation and IκB degradation, imply that HU stimulation may initiate a series of cell-stress signals, including NF-κB, to upregulate SAR1 expression, which subsequently elevates γ-globin transcription. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other factors to be identified might have distinct roles in regulating HU response and SAR1 transcription.

Overexpression of SAR1 alone can replicate the known effects of HU in K562 and CD34+ cells.15 This led to our interest in identifying whether SAR1 is required for HU-induced γ-globin production. Our results here indicate that blocking SAR1 expression significantly lowered both basal and HU-elicited HbF production in K562 and CD34+ cells and abolished HU-induced apoptosis in K562 cells, revealing a vital role of SAR1 in HbF expression and HU’s effects in these cells. These data suggest that SAR1 could be a potential therapeutic target for β-hemoglobinopathies.

Activation of JNK/Jun signaling could interact with the γ-globin promoter to increase its transcription and regulate erythroid cell differentiation.17,33 Heterotrimeric G proteins (G-proteins) consisting of α, β, and γ subunits are one kind of JNK/Jun upstream signaling protein that can be regulated by G-protein–coupled receptors, regulators of G-protein signaling, and activators of G-protein signaling.43 G-protein signaling regulates a variety of biological processes, including cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. Their functions are also implicated in erythroid differentiation44,45; in particular, the presence of Giα is required for hemin- and butyrate-mediated erythroid differentiation37,46,47 and erythropoietin-induced erythropoiesis.34,35 It has been reported that crosstalk occurs between small G-protein and heterotrimeric G proteins38,48,49; we therefore hypothesized that SAR1 might act through G-proteins to activate JNK/Jun and enhance HbF expression. This hypothesis was supported by several lines of evidence from the current studies. Overexpression of SAR1 activated Giα and increased the phosphorylation of JNK/Jun. Inhibition of JNK/Jun signaling by the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125 markedly reduced HbF expression in SAR1-transfected cells, and knockdown of Giα2 and Giα3 by siRNA substantially attenuated SAR1-stimulated Jun phosphorylation and γ-globin expression. Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation studies revealed an association between forcibly expressed SAR1 and Giα2 or Giα3 in both K562 and 293T cells. However, it should be noted that both Giα1 and Gαq had no effect on SAR1-regulated γ-globin expression, which may further attest to a distinct role of individual Giα proteins in the regulation of γ-globin expression in K562 and CD34+ cells.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, these results demonstrate for the first time that HU activates NF-κB to transcriptionally upregulate SAR1 expression and that SAR1 induces γ-globin expression predominantly through the Giα/JNK/Jun pathway in K562 and CD34+ cells. The specific function of SAR1 in upregulating γ-globin suggests that it may serve as a useful molecular target for upregulation of γ-globin gene expression and HbF levels in hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr John Hanover and Dr Lothar Hennighausen for valuable discussions and subsequent careful review of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge Dr Duck-Yeon Lee (Biochemistry Core Facility, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) for the expertise and advice regarding high-performance liquid chromatography use and data analysis.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.Z. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; K.C. contributed to immunofluorescence staining, the design of the study, and scientific discussion of the results; W.A. contributed to EMSA studies and analysis; C.K. contributed to the analysis of the flow cytometry data; H.L. contributed to the coimmunoprecipitation studies; and G.P.R. conceived and participated in the design of the study, the evaluation of the results, and the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Griffin P. Rodgers, Molecular and Clinical Hematology Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Building 10, Room 9N119, 10 Center Dr, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: gr5n@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0708272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh MM, Tisdale JF, Rodgers GP. Hemolytic anemia II: thalassemias and sickle cell disease. In: Rodgers GP, Young NS, editors. Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Hematology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham MJ, Macklin EA, Neufeld EJ, Cohen AR Thalassemia Clinical Research Network. Complications of beta-thalassemia major in North America. Blood. 2004;104(1):34–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rund D, Rachmilewitz E. Beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1135–1146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weatherall DJ. Pathophysiology of thalassaemia. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1998;11(1):127–146. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(98)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arruda VR, Lima CS, Saad ST, Costa FF. Successful use of hydroxyurea in beta-thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(13):964. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers GP, Dover GJ, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN, Nienhuis AW. Hematologic responses of patients with sickle cell disease to treatment with hydroxyurea. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(15):1037–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004123221504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankaran VG, Xu J, Ragoczy T, et al. Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature08243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cokic VP, Smith RD, Beleslin-Cokic BB, et al. Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin by the nitric oxide-dependent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):231–239. doi: 10.1172/JCI16672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladwin MT, Shelhamer JH, Ognibene FP, et al. Nitric oxide donor properties of hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;116(2):436–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikonomi P, Noguchi CT, Miller W, Kassahun H, Hardison R, Schechter AN. Levels of GATA-1/GATA-2 transcription factors modulate expression of embryonic and fetal hemoglobins. Gene. 2000;261(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Tang DC, Liu W, et al. Hydroxyurea exerts bi-modal dose-dependent effects on erythropoiesis in human cultured erythroid cells via distinct pathways. Br J Haematol. 2002;119(4):1098–1105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mabaera R, West RJ, Conine SJ, et al. A cell stress signaling model of fetal hemoglobin induction: what doesn’t kill red blood cells may make them stronger. Exp Hematol. 2008;36(9):1057–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JI, Choi HS, Jeong JS, Han JY, Kim IH. Involvement of p38 kinase in hydroxyurea-induced differentiation of K562 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12(9):481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang DC, Zhu J, Liu W, et al. The hydroxyurea-induced small GTP-binding protein SAR modulates gamma-globin gene expression in human erythroid cells. Blood. 2005;106(9):3256–3263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramakrishnan V, Pace BS. Regulation of γ-globin gene expression involves signaling through the p38 MAPK/CREB1 pathway. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;47(1):12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodeboyina S, Balamurugan P, Liu L, Pace BS. cJun modulates Ggamma-globin gene expression via an upstream cAMP response element. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;44(1):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs-Helber SM, Abutin RM, Tian C, Bondurant M, Wickrema A, Sawyer ST. Role of JunB in erythroid differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):4859–4866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Karmakar S, Dhar R, et al. Regulation of Gγ-globin gene by ATF2 and its associated proteins through the cAMP-response element. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e78253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adunyah SE, Chander R, Barner VK, Cooper RS, Copper RS. Regulation of c-jun mRNA expression by hydroxyurea in human K562 cells during erythroid differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1263(2):123–132. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00079-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Springer S, Spang A, Schekman R. A primer on vesicle budding. Cell. 1999;97(2):145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jardim DL, da Cunha AF, Duarte AS, dos Santos CO, Saad ST, Costa FF. Expression of Sara2 human gene in erythroid progenitors. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;38(3):328–333. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2005.38.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gubin AN, Njoroge JM, Bouffard GG, Miller JL. Gene expression in proliferating human erythroid cells. Genomics. 1999;59(2):168–177. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones B, Jones EL, Bonney SA, et al. Mutations in a Sar1 GTPase of COPII vesicles are associated with lipid absorption disorders. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):29–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green NS, Barral S. Genetic modifiers of HbF and response to hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(2):177–181. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumkhaek C, Taylor JG, VI, Zhu J, Hoppe C, Kato GJ, Rodgers GP. Fetal haemoglobin response to hydroxycarbamide treatment and sar1a promoter polymorphisms in sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(2):254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Chin K, Aerbajinai W, Trainor C, Gao P, Rodgers GP. Recombinant erythroid Kruppel-like factor fused to GATA1 up-regulates delta- and gamma-globin expression in erythroid cells. Blood. 2011;117(11):3045–3052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin KL, Aerbajinai W, Zhu J, et al. The regulation of OLFM4 expression in myeloid precursor cells relies on NF-kappaB transcription factor. Br J Haematol. 2008;143(3):421–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Peng C, Sankaran VG, et al. Correction of sickle cell disease in adult mice by interference with fetal hemoglobin silencing. Science. 2011;334(6058):993–996. doi: 10.1126/science.1211053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou D, Liu K, Sun CW, Pawlik KM, Townes TM. KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. Nat Genet. 2010;42(9):742–744. doi: 10.1038/ng.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tallack MR, Perkins AC. Three fingers on the switch: Krüppel-like factor 1 regulation of γ-globin to β-globin gene switching. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20(3):193–200. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32835f59ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stadhouders R, Aktuna S, Thongjuea S, et al. HBS1L-MYB intergenic variants modulate fetal hemoglobin via long-range MYB enhancers. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(4):1699–1710. doi: 10.1172/JCI71520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elagib KE, Xiao M, Hussaini IM, et al. Jun blockade of erythropoiesis: role for repression of GATA-1 by HERP2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(17):7779–7794. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7779-7794.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller BA, Foster K, Robishaw JD, Whitfield CF, Bell L, Cheung JY. Role of pertussis toxin-sensitive guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins in the response of erythroblasts to erythropoietin. Blood. 1991;77(3):486–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller BA, Bell L, Hansen CA, Robishaw JD, Linder ME, Cheung JY. G-protein alpha subunit Gi(alpha)2 mediates erythropoietin signal transduction in human erythroid precursors. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(8):1728–1736. doi: 10.1172/JCI118971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kesselring F, Spicher K, Porzig H. Changes in G protein pattern and in G protein-dependent signaling during erythropoietin- and dimethylsulfoxide-induced differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells. Blood. 1994;84(12):4088–4098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kucukkaya B, Arslan DO, Kan B. Role of G proteins and ERK activation in hemin-induced erythroid differentiation of K562 cells. Life Sci. 2006;78(11):1217–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takai Y, Sasaki T, Matozaki T. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(1):153–208. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moitreyee CK, Suraksha A, Swarup AS. Potential role of NF-kB and RXR beta like proteins in interferon induced HLA class I and beta globin gene transcription in K562 erythroleukaemia cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;178(1-2):103–112. doi: 10.1023/a:1006816806138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou CH, Huang J, Qian RL. Identification of a NF-kappaB site in the negative regulatory element (epsilon-NRAII) of human epsilon-globin gene and its binding protein NF-kappaB p50 in the nuclei of K562 cells. Cell Res. 2002;12(1):79–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrassy M, Bierhaus A, Hong M, et al. Erythropoietin-mediated decrease of the redox-sensitive transcription factor NF-kappaB is inversely correlated with the hemoglobin level. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58(3):179–189. doi: 10.5414/cnp58179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Z, Liebhaber SA. A 3′-flanking NF-kappaB site mediates developmental silencing of the human zeta-globin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18(8):2218–2228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blumer JB, Cismowski MJ, Sato M, Lanier SM. AGS proteins: receptor-independent activators of G-protein signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(9):470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Čokić VP, Smith RD, Biancotto A, Noguchi CT, Puri RK, Schechter AN. Globin gene expression in correlation with G protein-related genes during erythroid differentiation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amatruda TT, III, Steele DA, Slepak VZ, Simon MI. G alpha 16, a G protein alpha subunit specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(13):5587–5591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis MG, Kawai Y, Arinze IJ. Involvement of Gialpha2 in sodium butyrate-induced erythroblastic differentiation of K562 cells. Biochem J. 2000;346(Pt 2):455–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Kawai Y, Hanson RW, Arinze IJ. Sodium butyrate induces transcription from the G alpha(i2) gene promoter through multiple Sp1 sites in the promoter and by activating the MEK-ERK signal transduction pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(28):25742–25752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamauchi J, Kaziro Y, Itoh H. Differential regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) and 7 (MKK7) by signaling from G protein beta gamma subunit in human embryonal kidney 293 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(4):1957–1965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cismowski MJ, Ma C, Ribas C, et al. Activation of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by a ras-related protein. Implications for signal integration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(31):23421–23424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]