Abstract

Motivation: Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is one of the most widely used methods to measure gene expression. Despite extensive research in qPCR laboratory protocols, normalization and statistical analysis, little attention has been given to qPCR non-detects—those reactions failing to produce a minimum amount of signal.

Results: We show that the common methods of handling qPCR non-detects lead to biased inference. Furthermore, we show that non-detects do not represent data missing completely at random and likely represent missing data occurring not at random. We propose a model of the missing data mechanism and develop a method to directly model non-detects as missing data. Finally, we show that our approach results in a sizeable reduction in bias when estimating both absolute and differential gene expression.

Availability and implementation: The proposed algorithm is implemented in the R package, nondetects. This package also contains the raw data for the three example datasets used in this manuscript. The package is freely available at http://mnmccall.com/software and as part of the Bioconductor project.

Contact: mccallm@gmail.com

1 INTRODUCTION

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Bustin, 2000; Gibson et al., 1996; Higuchi et al., 1992; Wittwer et al., 1997) remains the gold standard for measuring gene expression due to a combination of greater sensitivity and lower cost than gene expression microarrays or RNA-sequencing. It is commonly used to validate results from high-throughput studies and to develop clinical biomarkers. Recently, qPCR-based technologies have been developed to simultaneously measure thousands of transcripts, e.g. the TaqMan OpenArray Real-Time PCR Plates contain 3072 wells. These plates have been used, for example, to simultaneously measure the expression of all microRNAs in a sample.

The increased use of qPCR (Ginzinger, 2002) has prompted research examining qPCR laboratory protocols (Bustin, 2002; Bustin and Nolan, 2004; Nolan et al., 2006) and more recently normalization (Mar et al., 2009; Mestdagh et al., 2009; Qureshi and Sacan, 2013) and statistical analysis strategies (Karlen et al., 2007; Schmittgen and Livak, 2008; Yuan et al., 2006). In 2009, the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines were published. These guidelines are designed to ‘encourage better experimental practice, allowing more reliable and unequivocal interpretation of qPCR results’ (Bustin et al., 2009).

Briefly, qPCR is used to measure the expression of a set of target genes in a given sample through repeated cycles of sequence-specific DNA amplification followed by expression measurements. Between subsequent cycles, the amount of each target transcript approximately doubles during the exponential phase of amplification. The cycle at which the observed expression first exceeds a fixed threshold is commonly called the threshold cycle (Ct) or quantification cycle (Cq). The latter is the MIQE-preferred nomenclature but is not currently widely used. These Ct values represent a quantitative assessment of gene expression and are often treated as the raw data for subsequent analyses.

However, relatively little attention has been given to handling non-detects—those reactions failing to attain the prespecified minimum signal intensity. Currently, there is no consensus manner in which to handle these non-detects in subsequent analyses. The default in the Applied Biosystems DataAssist v3.0 software is to set non-detects equal to the number of PCR cycles performed (typically 40). One has the option of setting a lower Maximum Allowable Ct Value to which any greater value is set or excluding these values from subsequent calculations (Life Technologies, 2011). Integromics RealTime StatMiner distinguishes between two types of non-detects—undetermined values are those that do not exceed the Ct threshold and absent values are those for which no reaction occurred. RealTime StatMinder handles non-detects by setting undetermined values to a maximum Ct (e.g. 40) and absent values to the median of the detected replicates (Goni et al., 2009). Researchers have also developed their own methods to handle non-detects that combine filtering and thresholding, for example, summarizing replicates with a value of 40 when the majority are non-detects and with an average of the detected Ct values otherwise (Mar et al., 2009).

2 APPROACH

We begin by showing that the common practice of setting non-detect values equal to 40 introduces substantial bias in normalized gene expression, ΔCt, and differential expression, ΔΔCt, estimates (Pfaffl, 2001). Next, we provide evidence that non-detects are not missing completely at random and are likely missing not at random; therefore, filtering these data will also introduce bias in subsequent analyses (for an introduction to missing data terminology, see Gelman and Hill, 2007, Chap. 25). To address non-detects, we propose a method to model the missing data mechanism that can be used to impute Ct values for the non-detects or to directly estimate the quantities of interest. Finally, we show that the proposed approach greatly reduces the bias introduced by non-detects in qPCR data analysis. Three published qPCR datasets (described in the Methods Section) are used throughout the manuscript to motivate and illustrate the results.

3 METHODS

3.1 Three example datasets

The first dataset consists of nine gene perturbations with matched control samples (Almudevar et al., 2011); the second dataset is composed of two cell types and three treatments (Sampson et al., 2013); the third dataset is a study of the effect of p53 and/or Ras mutations on gene expression (McMurray et al., 2008).

In the first dataset, cells transformed to malignancy by mutant p53 and activated Ras are perturbed with the aim of restoring gene expression to levels found in non-transformed parental cells via retrovirus-mediated re-expression of corresponding cDNAs or shRNA-dependent stable knock-down. The data contain four to six replicates for each perturbation, and each perturbation has a corresponding control sample in which only the vector has been added (Almudevar et al., 2011).

The second dataset consists of two cell types—young adult mouse colon (YAMC) cells and mutant-p53/activated-Ras transformed YAMC cells—in combination with three treatments—untreated, sodium butyrate or valproic acid. Four replicates were performed for each cell-type/treatment combination (Sampson et al., 2013).

The third dataset is a comparison between four cell types—YAMC cells, mutant-p53 YAMC cells, activated-Ras YAMC cells and p53/Ras double mutant YAMC cells. Three replicates were performed for the untransformed YAMC cells, and four replicates were performed for each of the other cell types (McMurray et al., 2008).

As in the original publications, all three datasets were normalized to a reference gene, Becn1, with the resulting values denoted as ΔCt. In the first dataset, ΔΔCt values were computed by comparing each perturbed sample to its corresponding control sample. Additional details regarding each of these datasets can be found in the original publications.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Setting non-detects equal to 40 introduces bias

We begin by examining the common practice of replacing non-detects with a Ct value of 40. Replicates were summarized by calculating the average ΔCt (datasets 2 and 3) or ΔΔCt (dataset 1) values for each unique gene/sample-type combination. The residuals from this summarization for gene i, sample-type j and sample k were calculated as follows:

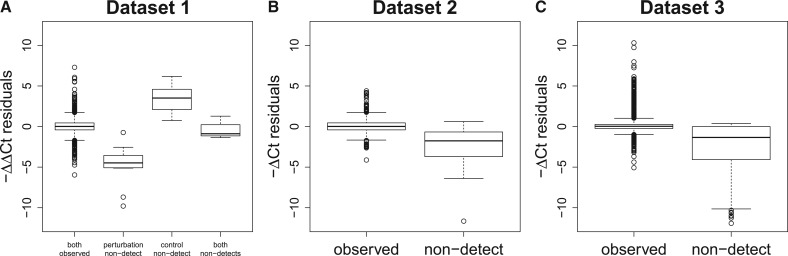

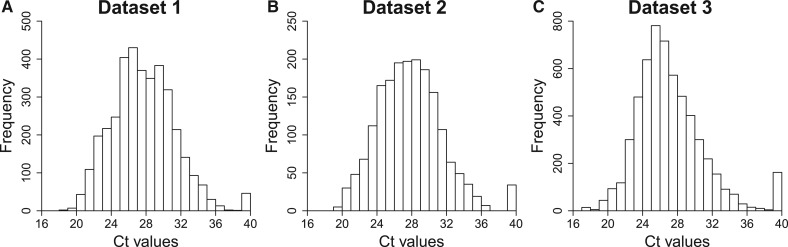

The distribution of these residuals differs substantially between those in which the or value contains a non-detect and those in which these values were observed (Fig. 1). Note that when calculating ΔCt values, the reference gene, Becn1, is always detected, so non-detects can only occur in the target gene; therefore, datasets 2 and 3 are each split into two groups based on whether both Ct values were observed or a non-detect was present in the target gene. A non-detect typically results in lower absolute expression estimates (Fig. 1B and C). When calculating ΔΔCt values, a non-detect can occur in the perturbed and/or control sample. In general, a non-detect in the perturbed sample results in lower relative expression, and a non-detect ina the control sample results in higher relative expression (Fig. 1A). Non-detects in both samples yield ΔΔCt values close to zero—these values simply represent differences in Becn1 expression between the perturbed and control samples. While one might expect some difference in the distribution of residuals between the observed values and those containing a non-detect, the large differences seen in Figure 1 likely represent bias introduced by the common method of handling non-detects.

Fig. 1.

Within replicate residuals stratified by the presence of non-detects. The average ΔΔCt (A) or ΔCt (B and C) values were calculated within each set of replicates (same gene and sample type). The residuals, for each gene and sample from this summarization are plotted here, stratified by the presence of non-detects. In dataset 1, a non-detect could occur in the perturbation sample, the control sample or both samples. The left-most box in Panel A shows the distribution of residuals in dataset 1 when there are no non-detects. The other boxes in Panel A (from left to right) show the distribution of residuals when there are non-detects in the perturbation sample, the control sample and both samples. Similarly, the left box in Panels B and C shows the distribution of residuals when there are no non-detects. The right box in Panels B and C shows the distribution of residuals when there is a non-detect. Although one would expect some difference in the distribution of residuals between the detects and non-detects, the differences seen here are much larger than one would expect and likely represent bias introduced by setting non-detects equal to 40

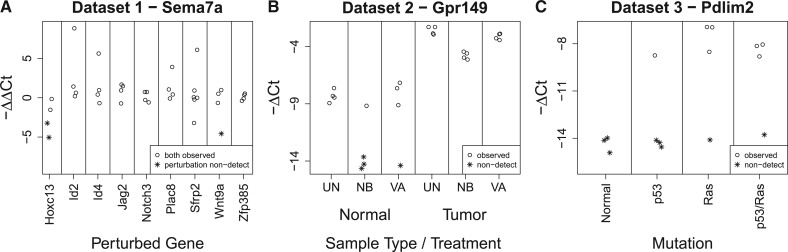

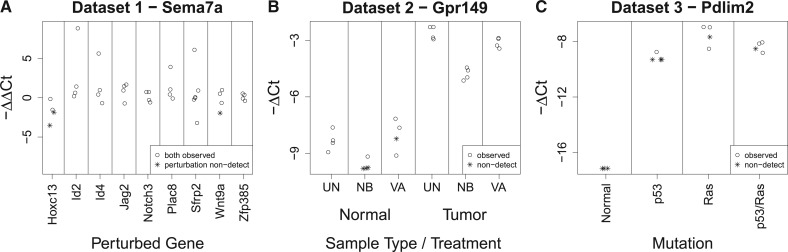

To further illustrate the bias introduced by replacing non-detects with a value of 40, the ΔCt and ΔΔCt values for one example gene from each dataset are shown in Figure 2. These examples were chosen to demonstrate situations in which replacing non-detects with a value of 40 may lead to spurious differential expression.

Fig. 2.

Examples of the potential for spurious differential expression produced by replacing non-detects with values of 40. Panel (A) shows the response of Sema7a to the perturbation of nine genes from dataset 1. Panel (B) shows the expression of Gpr149 in each combination of normal/tumor samples and one of three treatments from dataset 2. Panel (C) shows the response of Pdlim2 to p53 and/or Ras mutation from dataset 3. ΔCt and ΔΔCt values produced by replacing a non-detect with a value of 40 are shown as asterisks. Note that in panel A, a non-detect could have also occurred in one of the control samples; however, in these data this did not occur for Sema7a—all of the non-detects happened to occur in the perturbed samples

In Figure 2A, the response of Sema7a to perturbation of each of nine genes is shown. Looking at only the ΔΔCt values for which there were no non-detects, the expression of Sema7a does not appear to be greatly affected by any of the perturbations, except perhaps Hoxc13. However, there do appear to be a relatively large number of outliers. Focusing on Sema7a’s response to perturbation of Hoxc13, half of the ΔΔCt values contained a non-detect in the perturbed sample. If one replaced these non-detects with a value of 40, the resulting ΔΔCt values would be approximately −3.23 and −5.05, while the ΔΔCt values without non-detects were approximately −0.16 and −1.54. This would produce an average ΔΔCt value of −2.5. This is probably a substantial overestimate of the down-regulation of Sema7a induced by perturbation of Hoxc13, resulting from the common method of handling non-detects.

Figure 2B shows the expression of Gpr149 in six conditions. Among the normal samples, there does not appear to be a difference in expression between the untreated (UT), sodium butyrate (NB) and valproic acid (VA) samples when looking at only the ΔCt values without non-detects. However, there are three non-detects in the NB samples and one in the VA sample. Replacing these non-detects with a value of 40 would lead to a large (and likely spurious) difference in expression between these treatments.

Finally, Figure 2C shows the response of Pdlim2 to mutation of p53 and/or Ras. While there are non-detects in each group, the number of non-detects varies from 3/3 in the normal samples to 1/4 in the Ras and p53/Ras samples. Replacing these non-detects with a value of 40 will produce a sizeable difference in average expression between the normal and p53 samples and the Ras and p53/Ras samples.

4.2 Filtering non-detect Ct values also introduces bias

Whether one can filter missing values from one’s data without biasing one’s results depends on the type of missing data. Data are said to be missing completely at random if the probability of a missing value is the same for all data points. For qPCR data this implies that the probability of a non-detect is the same for every data point regardless of gene, sample-type, sample-replicate, etc. A broader class of missing data is missing at random in which the probability of a missing value depends only on the available information. For qPCR data this would imply that the probability of a non-detect is the same for each replicate within a given gene/sample-type combination. Finally, the data are called missing not at random when the probability of a missing value depends on either unobserved predictors or the missing value itself. A well-studied example of the latter is censoring. For data missing not at random, filtering the missing values produces bias in one’s inferences.

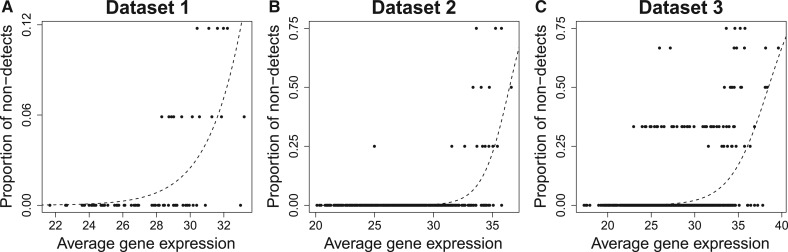

If the non-detects are missing completely at random, then the proportion of non-detects should be roughly constant across genes. For each gene, we compute the proportion of non-detects and the average Ct value across replicate samples (Fig. 3). There appears to be a strong relationship between the average expression of the genes across replicate samples and the proportion of non-detects. In other words, it seems that genes with lower average expression are far more likely to be non-detects. From this we can conclude that the non-detects do not occur completely at random.

Fig. 3.

The proportion of non-detects versus median observed gene expression within control samples (A) or within each sample condition (B and C). Logistic regression fits (dashed lines) all show a strong relationship between the proportion of non-detects and the median observed gene expression—P-values of (A) , (B) , (C)

While it is relatively easy to distinguish between missing completely at random and missing at random, it is generally not possible to distinguish between missing at random and missing not at random from the observed data. However, in the case of qPCR non-detects, we are able to use two pieces of additional information to suggest that non-detects are likely missing not at random.

First, the PCR reactions are run for a fixed number of cycles (typically 40), implying that the observed data are censored at the maximum cycle number. This is a type of non-random missingness in which the missing data mechanism depends on the unobserved value. Knowledge of the technology allows us to conclude that the data are at least subject to fixed censoring; however, as we will later show, the qPCR censoring mechanism may actually be a probabilistic function of the unobserved data.

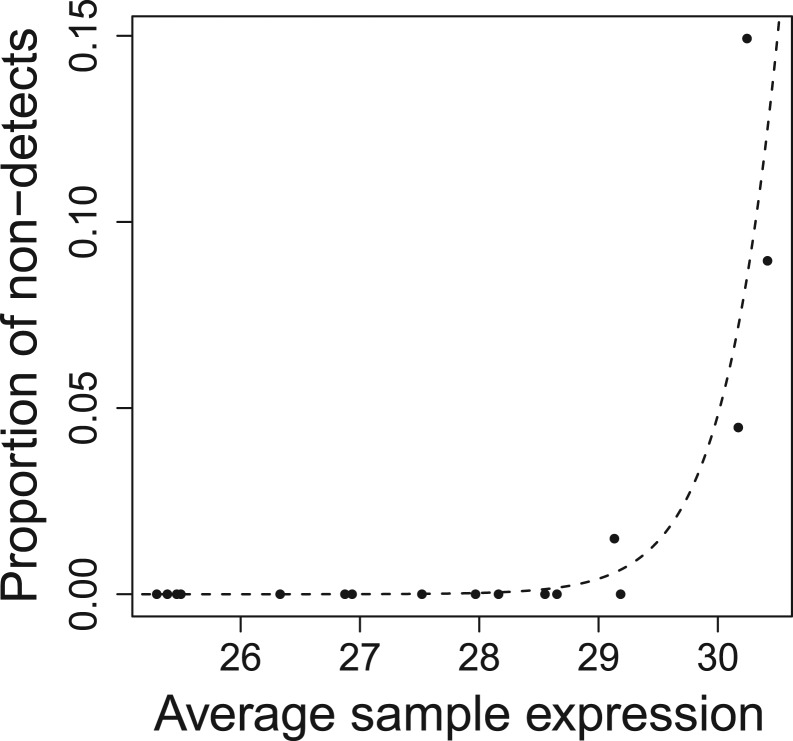

Second, the experimental design of the first dataset, in which there are a large number of control samples, allows one to estimate an additional piece of information that is not typically available—the proportion of non-detects as a function of the average sample expression across a large number of replicates (Fig. 4). Here, we see a similar relationship between average expression and proportion of non-detects. It appears that samples with overall lower signal, as a result of technical not biological variability, also result in a greater number of non-detects. Because most qPCR experiments are not designed to allow one to estimate the relationship between overall sample signal and the proportion of non-detects, qPCR data typically exhibit a type of non-random missingness in which the missing data mechanism depends on an unobserved variable.

Fig. 4.

The proportion of non-detects versus median sample expression within controls in dataset 1. Logistic regression fit (dashed line) shows a strong relationship between the proportion of non-detects and the median gene expression—P-value of 0.0003

This suggests that qPCR non-detects are probably not missing at random; therefore, filtering non-detects will introduce bias in one’s inference. The only principled approach is to attempt to model the missing data mechanism and incorporate this into one’s analysis.

4.3 The missing data mechanism

Before proposing a missing data mechanism for qPCR non-detects, it is important to first determine what a non-detect represents. There are several possibilities:

Truncation of a continuous expression distribution—a non-detect represents a true Ct value >40. This implies that if the PCR were run for more cycles, one would eventually see an amplification above the Ct threshold. This would mean that the Ct values are a type of censored data.

A completely unexpressed transcript—no matter how long the PCR was run, one would never see amplification above the Ct threshold.

A failure to detect a true Ct value <40—the Ct value should be <40, but in the given experiment the transcript failed to amplify or its amplification efficiency was poor.

We begin by evaluating the first potential explanation for non-detects by examining the distribution of Ct values including non-detects coded as 40 (Fig. 5). The number of non-detects in these datasets far exceeds what one would expect based on fitting a normal distribution to the detected Ct values. Approximately 1.2, 1.8 and 2.8% of the measurements are non-detects in datasets 1, 2 and 3, respectively, where one would expect 0.02, 0.03 and <0.01%. This argues against non-detects being explained completely by a truncation of the Ct value distribution, unless the distribution has an extremely long upper tail.

Fig. 5.

The distribution of Ct values in each of the three datasets. Here, non-detects are coded as 40

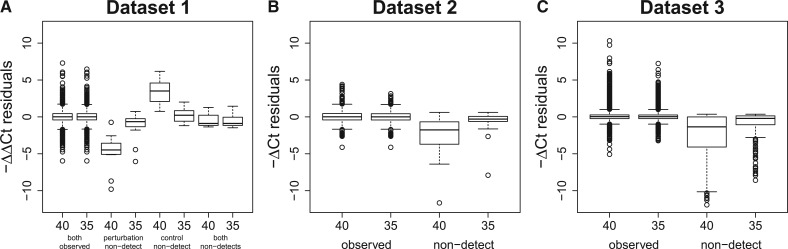

Furthermore, if the non-detects represented censoring of values >40, one would expect a reduction in bias by replacing the non-detects with a value ≥40. However, in general, bias is reduced by replacing non-detects with a value of 35 rather than 40 (Fig. 6). This suggests that many non-detects are due to a failure to amplify rather than a true Ct value >40.

Fig. 6.

Same as Figure 1, with additional boxplots showing the residuals when non-detects are replaced with 35 rather than 40. Here, Ct values >35 are also replaced by a value of 35. By replacing non-detects with a value of 35 rather than 40, the distribution of the residuals is far more similar between those in which the Ct values were observed and those containing a non-detect. However, this does not imply that one should replace non-detects with a value of 35. Such an approach makes very strong assumptions about the missing data mechanism and would require one to discard observed Ct values >35

Next, we evaluate the second potential explanation for non-detects—that a non-detect represents a completely unexpressed transcript. As previously mentioned, Figure 4 shows a strong relationship between low overall signal in a sample and a greater proportion of non-detects. Although some non-detects may represent a completely unexpressed gene, this cannot be the only explanation, given that samples with low signal (due to technical not biological differences) typically have a greater proportion of non-detects.

Finally, examination of Figure 5 shows a relatively low number of Ct values between 35 and 40. Together with Figure 6, in which replacing non-detects with a value of 35 rather than 40 reduced the bias in ΔCt and ΔΔCt values, this suggests that some non-detects represent a failure to detect a true Ct value <40.

4.4 A potential generative model

One model to explain the observed behavior of non-detects in the Ct data is the following:

where

Here, Yij is the observed Ct value of gene i for sample j, is the true expression of gene i for sample j, represents the non-biological effects present in the observed data and captures the technical and biological variability in the data. Zij is a binary variable representing whether a Ct value was obtained for gene i and sample j that takes on a value of 1 with probability for values of Yij less than some threshold Sij. Here, Sij represents the upper Ct value detection limit for gene i and sample j.

In this framework, one can represent the standard assumptions regarding non-detects as: (i) , where 40 is the total number of PCR cycles performed and (ii) meaning that Ct values <40 are never reported as non-detects. However, the results shown above suggest that these assumptions are probably not valid. Specifically, Sij may be <40 for some genes and/or may be <1.

Furthermore, this model captures several important aspects of qPCR non-detects. The relationship between technical variability in expression and the proportion of non-detects is formalized in the dependence of Zij on Yij rather than . The gap in observed Ct values between 35 and 40, i.e. the potential for Ct values to be non-detects, is captured by and/or .

4.5 An EM algorithm to handle non-detects

Having established that non-detects in qPCR data represent data missing not at random, we now propose a method that incorporates the missing data mechanism into subsequent statistical analyses. The expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm provides a method to obtain maximum likelihood estimates in the presence of missing data by iteratively calculating the conditional expectation:

and maximizing with respect to ϕ. Here, X is the complete unobserved data and Y is the incomplete observed data, ϕ is the set of all parameters, is the complete data log-likelihood, and is the estimate of ϕ at iteration n. This process is repeated until convergence (Dempster et al., 1977).

The challenging aspect of applying the EM algorithm to qPCR non-detects is calculating the conditional expectation. This requires one to estimate the distribution of gene expression given a non-detect. Here, we proceed via Bayes rule:

We can estimate by examining the relationship between the proportion of non-detects and average observed expression within replicates. This approach permits flexible modeling of the data to either directly estimate the parameters of interest or to obtain estimates of the missing data that can be used to impute the non-detect values.

To demonstrate the reduction in bias that one can achieve by treating non-detects as missing data, we propose the following model of the observed expression for gene i, sample-type j and replicate k, Yijk:

where represents a global shift in expression across samples and,

Here, can be estimated via the following logistic regression:

where is an estimate of the average expression for gene i and sample-type j. For the data presented here, can be estimated using the reference gene, Becn1.

4.6 Treating non-detects as missing data reduces bias

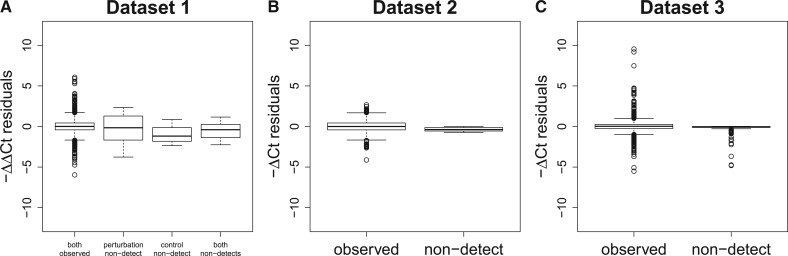

We begin by examining the effect of replacing non-detects with an imputed Ct value based on the conditional expectation calculated in the EM algorithm. Looking at the residuals within replicates in each dataset, it is clear that replacing non-detects with these imputed values results in far less bias in the ΔCt and ΔΔCt values than if we replaced the non-detects with a value of 40 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Same as Figure 1, but after imputing the non-detects using the proposed EM algorithm

The improvement in bias after imputing the non-detects can also be seen in the example genes shown in Figure 2. After replacing the non-detects with values imputed using the EM algorithm, the non-detect ΔCt and ΔΔCt values are far more similar to their replicate values, while retaining small differences due to the informative missingness (Fig. 8). Figure 8C shows one important limitation of the current implementation. Because the ΔCt values from the three normal samples all contained non-detects, their imputed values are fairly similar to the initial values based on replacing the non-detects with a value of 40. One could address this by implementing a slightly more complex EM algorithm that shrinks the imputed values toward a global mean; however, such an approach assumes that Pdlim2 is actually expressed in the normal samples in dataset 3. Given that all three replicates resulted in a non-detect, it may be that Pdlim2 is truly unexpressed in these samples. Any modeling for such situations will depend on the specific dataset being analyzed and the biological plausibility of the potential assumptions.

Fig. 8.

Same as Figure 2, but after EM imputation of non-detects

One can also use the EM algorithm to directly estimate the parameters of interest. In the example datasets reported here, these might be the average expression of each gene within each sample-type, . Alternatively, one could use this framework to directly estimate the ΔCt or ΔΔCt values. Furthermore, the EM algorithm allows one to easily combine the treatment of non-detects with more complex statistical analyses.

5 DISCUSSION

In this manuscript, we have shown that the default procedure of replacing qPCR non-detects with the maximum PCR cycle number (typically 40) introduces a large bias in subsequent inference. We have carefully examined the nature of non-detects and shown that they likely represent data missing not at random. Furthermore, we have shown that many non-detects represent an amplification failure rather than a true Ct value >40. Finally, we propose a relatively simple EM algorithm and show that it is able to greatly reduce the bias caused by non-detects. The flexibility of our approach allows one to easily tailor the method described here to one’s own analyses. Specifically, one could easily use a different normalization procedure or perform a more complex statistical analysis. Additionally, any analysis based on imputed values (rather than direct estimation of a parameter of interest) would benefit from a multiple imputation procedure.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (grant numbers CA009363, CA138249, HG006853); and an Edelman-Gardner Foundation Award.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Almudevar A, et al. Fitting Boolean networks from steady state perturbation data. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2011;10:47. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;29:23–39. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;25:169–193. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Nolan T. Pitfalls of quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. J. Biomol. Tech. 2004;15:155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson U, et al. A novel method for real time quantitative RT-PCR. Genome Res. 1996;6:995–1001. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.10.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzinger DG. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:503–512. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni R, et al. Integromics White Paper. Integromics SL; 2009. The qPCR data statistical analysis; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R, et al. Simultaneous amplification and detection of specific DNA sequences. Biotechnology. 1992;10:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nbt0492-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlen Y, et al. Statistical significance of quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Life Technologies. 2011. DataAssist v3.0 Software user instructions. [Google Scholar]

- Mar JC, et al. Data-driven normalization strategies for high-throughput quantitative RT-PCR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray HR, et al. Synergistic response to oncogenic mutations defines gene class critical to cancer phenotype. Nature. 2008;453:1112–1116. doi: 10.1038/nature06973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestdagh P, et al. A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T, et al. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1559–1582. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi R, Sacan A. A novel method for the normalization of microRNA RT-PCR data. BMC Med. Genomics. 2013;6(Suppl. 1):S14. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson E, et al. Gene signature critical to cancer phenotype as a paradigm for anticancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2013;32:3809–18. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer CT, et al. Continuous fluorescence monitoring of rapid cycle DNA amplification. Biotechniques. 1997;22:130–139. doi: 10.2144/97221bi01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JS, et al. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]