Abstract

The past two years have seen a number of basic and translational science advances in the quest for development of an effective HIV-1 vaccine. These advances include discovery of new envelope (Env) targets of potentially protective antibodies, demonstration that CD8+ T cells can control HIV-1 infection, development of immunogens to overcome HIV-1 T cell epitope diversity, identification of correlates of transmission risk in an HIV-1 efficacy trial, and mapping the co-evolution of HIV-1 founder Env mutants in infected individuals who develop bnAbs, thereby defining broad neutralizing antibody (bnAb) developmental pathways. Despite these advances, a promising HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial published in 2013 failed to prevent infection, and the HIV-1 vaccine field is still years away from deployment of an effective vaccine. This review summarizes what some of the scientific advances have been, what roadblocks still remain, and what the most promising approaches are for progress in design of successful HIV-1 vaccine candidates.

Keywords: HIV-1, vaccine, T cells, B cells, broadly neutralizing antibodies

Introduction

Development of a safe and effective HIV-1 vaccine is a global priority 1. The HIV-1 vaccine field is 30 years into the effort, yet there is no effective vaccine currently available. However, recent breakthroughs in the HIV-1 vaccine field have buoyed hopes that progress can now be made towards an effective vaccine. These advances include discovery of new envelope (Env) targets of potentially protective antibodies 2, 3, demonstration in proof of concept studies that CD8+ T cells can control HIV-1 infection 4, 5, development of immunogens to overcome HIV-1 T cell epitope diversity 6-9, identification of correlates of transmission risk in the first HIV-1 efficacy trial to show any protection 10-13, and mapping the evolution of the founder Env mutants in individuals who develop bnAbs, thereby defining broad neutralizing antibody (bnAb) development pathways 14.

Current roadblocks to HIV-1 vaccine development are the inability to induce antibody responses to desired conserved bnAb envelope regions 3 and difficulty in overcoming HIV-1 diversity 9. Nonetheless, as outlined below, progress is being made in understanding the nature of the roadblocks and in devising strategies for overcoming these roadblocks.

New breakthroughs in HIV-1 vaccine research

This year the field had a major disappointment in the announcement of the lack of vaccine efficacy seen in a DNA prime, recombinant adenovirus type 5 (rAd5) boost HIV-1 vaccine trial developed by the NIH Vaccine Research Center 15. This vaccine was designed primarily to test the hypothesis that high levels of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) could either protect against transmission or lead to control of plasma HIV-1 viral load. While a majority of vaccinees made T-cell responses as well as envelope-binding antibody levels, the trial showed no efficacy against HIV-1 acquisition 15. Although additional efficacy trials with a new generation of vaccines are likely in future years, the two HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial candidates that were primarily targeted to eliciting CD8+ T cells cytotoxic for HIV-infected CD4+ T cells that have been tested have both failed to demonstrate protective efficacy. The second failed trial, the Merck recombinant adenovirus type 5 trial, not only lacked vaccine efficacy, but also appeared to enhance infection in those vaccinees seropositive for Ad5 16. However, even HIV-1 efficacy trials that lack protective efficacy can provide information on the types of immune responses that are unlikely to be protective 17, 18.

A new set of studies by Hansen et al. 4, 5 have demonstrated in rhesus macaques that a replicating cytomegalovirus (CMV) vector expressing Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) antigens could eradicate early SIV infection in 50% of SIV-challenged rhesus macaques. Moreover, SIV-infected cell eradication was associated with an unusual form of CD8+ T cell killing in which CD8+ T cells recognized SIV peptides presented in the context of MHC class II molecules instead of the classical MHC class I 5. Thus, the search is on to find safe CMV-like vectors that might recreate this activity in humans exposed to HIV-1, and intense research is ongoing to explain why the protective effect was only seen in 50% of rhesus macaques. Nonetheless, these data have demonstrated that indeed CD8+ T cells are associated with control and eradication of early retrovirus infections.

The single trial of an HIV-1 vaccine that showed any efficacy was the RV144 canarypox prime, gp120 protein boost vaccine trial carried out in Thailand that reported an estimated vaccine efficacy of 31.2% 11. This level of efficacy was not sufficient for deployment of the vaccine, but was encouraging to the field as it suggested that a preventive vaccine could be made 19. An immune correlates study of the RV144 trial demonstrated that plasma antibodies to the second variable region of the gp120 envelope correlated with decreased HIV-1 transmission risk. In addition, plasma Env IgA responses correlated with decreased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy 10. Follow-up correlates analyses demonstrated the robustness and breadth of the IgG correlate of risk across multiple subtypes of V1V2 antigens 13. A genetic analysis of RV144 breakthrough viruses in vaccinees and placebos demonstrated the site of immune pressure to be a single lysine residue (K169) in the second variable (V2) region of Env 20. Isolation of V2 monoclonal antibodies demonstrated that antibodies that bound to K169 neither broadly bound transmitted/founder virions nor neutralized difficult-to-neutralize (tier 2) viruses, but did neutralize the vaccine strain virus, 92Th023 21, mediated low level virion capture 21-23, and mediated antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) 21, 24. RV144 induced V1V2 IgG3 antibody responses correlated with decreased risk of HIV-1 infection 25 and correlated with ADCC in the RV144 trial 25, 26. The Env IgG3 response declined quickly post vaccination 25 as did the overall vaccine efficacy 27, raising the question that the quantity of the antibody levels post vaccination may have contributed to a lowered vaccine efficacy.

Studies to understand correlates of HIV-1 risk in RV144 have also focused on understanding the mechanisms of specific Env IgA in decreasing HIV-1 vaccine efficacy. We found that HIV-1 Env IgA to a conformational C1 region in gp120 blocked IgG mediated ADCC, thus providing a rationale that vaccine-induced plasma IgA responses that bind to the same epitope on infected target cells as IgG could indeed block IgG NK mediated effector function 17. Consequently, new vaccine candidates are now being designed to increase the breadth of induced FcR-mediated IgG anti-HIV activity, and to optimize the vaccine- induced antibody subclass (i.e. IgG3) and isotype profile 25. Moreover, efforts are being made to increase antibody durability by incorporating a new adjuvant into the regimen, to determine if efficacy induced by an ALVAC prime, gp120 boost vaccine can be improved to the point of being clinically useful. However, the specific roles of ADCC-mediating antibodies and other FcR-mediated antibody functions in prevention of HIV-1 remains to be directly shown. Roederer et al. 28 have recently shown that current vaccines can induce antibodies that neutralize a subset of SIV viruses. These data suggested that partial efficacy in vaccine trials may be due to vaccine-induced neutralization of a small subset of sensitive viral quasispecies.

New progress has been made in overcoming HIV-1 diversity by induction of cross-reactive T cell responses to HIV-1 by vaccines designed in silico (called conserved and mosaic vaccines) 8, 29, 30. These in silico designed immunogens are constructed to increase the coverage across both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell epitopes, and studies in non-human primates have demonstrated that indeed this is the case. Clinical trials with the conserved gene inserts are ongoing, and Phase I clinical trials with mosaic vaccines are planned to begin this year.

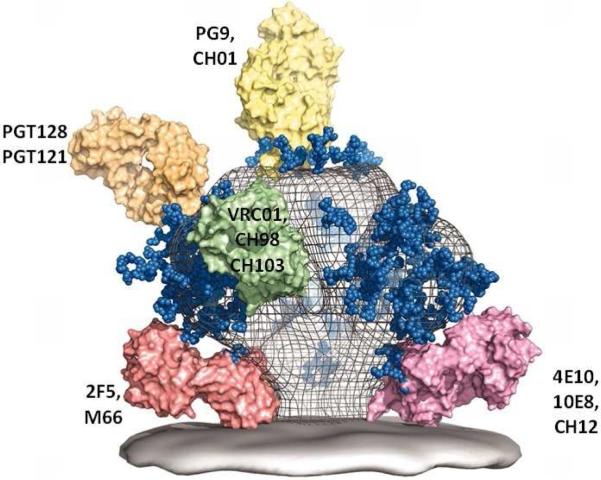

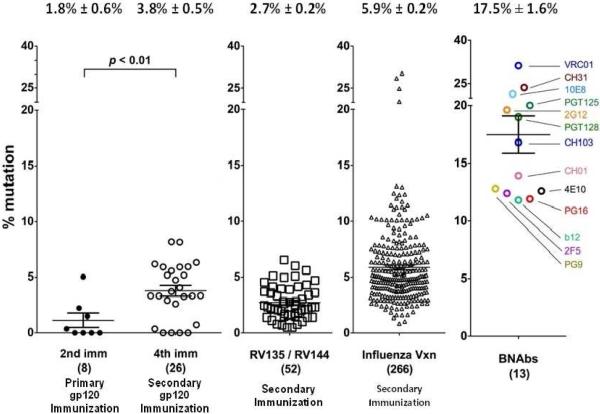

The holy grail of HIV-1 vaccine development continues to be the induction of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) 3, 31. Although the HIV-1 envelope does have conserved regions to which neutralizing antibodies can bind 32, no current vaccine candidates have been able induce high levels of bnAbs 2, 31, 32. The recent development of methods for generating recombinant antibody from single cells 33, the efficient isolation of individual plasmacytes and antigen-specific B cells by flow cytometry sorting 34-36, and high throughput clonal memory B cell cultures 37, 38 has permitted a host of new bnAbs to be recovered from HIV-1 infected individuals. HIV-1 bnAbs define four conserved Env targets for HIV neutralization 2, 3 (Figure 1). More than 30 bnAbs specific for conserved neutralizing Env epitopes have been isolated and characterized 3. It has become clear that all bnAbs share one or more unusual characteristics: extraordinary levels of somatic hypermutation (Figure 2), autoreactivty for host molecules, and long antibody heavy chain complementarity determining region 3s (HCDR3s) 31, 32, 39. All of these traits are associated with direct or indirect control by host tolerance and immunoregulatory mechanisms, raising the hypothesis that a major regulator of HIV-1 bnAb generation is immune tolerance 31, 40, 41.

Fig. 1.

A model of the HIV-1-1 Env spike with select bnAb Fab molecules bound to bnAb sites 2.

Fig. 2. Comparison of Heavy Chain Mutation Frequency in HIV-1 Immunization, Influenza Immunization, and HIV-1 Broad Neutralizing Abs.

Heavy chain (HC) mutation frequencies were determined for three different vaccine studies and compared to that of well-characterized bnAbs. The left two columns show HC mutation frequencies induced by two or four immunizations of a gp120 immunogen 77, there was a rise in mutation observed with repeated immunization. The third column shows an intermediate degree of mutation frequencies observed among antibodies isolated from the canarypox-prime Env-boost RV144 regimen in Phase II and III trials 38. The fourth column is the mutation frequency observed for influenza vaccine recipients 78; mutation frequencies after repeated exposure to influenza are higher than those for HIV-1 vaccines. The last column shows 13 well characterized bnAbs all of which show an exceptional degree of mutation.

In 2005, Haynes and colleagues made the observation that two human recombinant bnAbs, called 2F5 and 4E10, that bind near the virion membrane to envelope gp41 were reactive in human autoantibody assays 40. In a subsequent study, 2F5 was shown to avidly bind the human protein kynureninase (KYNU), and 4E10 was shown to react with the mammalian RNA splicing factor 3B3 42. For 2F5 reactivity with KYNU, the molecular mimicry is striking—the nominal gp41 epitope of the 2F5 bnAb is the linear peptide ELDKWAS and an identical six-residue sequence is present in KYNU (ELDKWA). This ELDKWA motif in KYNU is conserved in nearly all mammalian species and absent in all proteins other than the HIV Env 42. Thus, the autoantigens for these two bnAbs, 2F5 and 4E10, have been identified, suggesting that expression of these bnAbs is limited by host tolerance mechanisms.

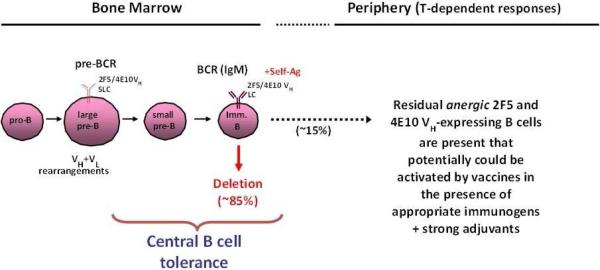

To determine directly whether expression of 2F5-like antibody is indeed controlled by immune tolerance, Verkoczy et al. constructed knockin mouse strains carrying the 2F5 bnAb genes 43-45. BnAb knockin mice exhibited a severe block in B-cell development at the transition between pre-B and immature B cells. This developmental blockade represented the first tolerance checkpoint and was consistent with physiologically significant autoreactivity by both the mature and germline forms of the 2F5 antibody (Figure 3). The 2F5 knockin mouse strain also offered potentially good news for vaccine development. Although the vast majority (95%) of B cells expressing the 2F5 antibody were deleted at the first tolerance checkpoint, a small but significant fraction (5%) of 2F5+ B cells escaped this checkpoint but were functionally silenced (anergic) 43-45. Remarkably, these anergic B cells could be activated by an immunogen that mimicked the membrane proximal region of gp41 to elicit plasma 2F5 bnAbs 45, 46. Recently, it has been shown that the 4E10 HIV-1 bnAb is similarly controlled by tolerance deletion and anergy control mechanisms 46, 47. A naturally occurring 2F5-like mAb in a HIV-1-infected individual has been isolated as well 48, 49, lending plausibility for gp41 neutralizing antibody induction by a vaccine.

Fig. 3. Central deletion of B-cells expressing gp41 broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Highlighted is the pre-B to immature B-cell transition, the stage of B-cell development in the bone marrow at which most B cells expressing 4E10 or 2F5 bnAbs (as BCRs) have been demonstrated in knockin mice to be profoundly impaired 44, 47, 79. This stage also coincides with the first general checkpoint at which B-cell tolerance mechanisms, including apoptotic deletion, begin to occur 31, 39.

BnAbs specific for the HIV-1 envelope gp120 V1V2 glycan bnAb Env region uniformly carry unusually long antibody HCDR3 sequences that appear to be necessary for neutralization 3. It is likely that these rare HCDR3 motifs are necessary for the bnAb paratope to reach in and around glycans for avid binding at the variable loops of HIV-1 Env 50-57. In humans, the population of B cells expressing antigen receptors with exceptionally long antibody HCDR3s are controlled by tolerance mechanisms, and this population is commonly reduced by deletion at the first tolerance checkpoint in bone marrow 58. Therefore, the precursors of V1V2 glycan antibodies are similarly derived from a rare pool of B cells controlled by tolerance mechanisms.

As mentioned, all HIV-1 bnAbs have been shown to carry significantly higher frequencies of V(D)J mutations than non-HIV-1 antibodies 3 (Figure 3). Among the known bnAbs, CD4 binding site (CD4bs) antibodies of the VRC01-type (a type of bnAb shaped like the CD4 molecule itself) have the highest levels of somatic hypermutation (SHM), often reaching [.approxequal]30%. Many of these antibodies are also autoreactive; interestingly, the most common self-antigen recognized by several CD4bs bnAbs are ubiquitin ligases 14, 59 (Kelsoe, G, unpublished observations). The extraordinary frequency of point as well as insertion/deletion mutations in HIV-1 bnAbs is both puzzling and, perhaps, a significant clue towards determining why bnAbs are so difficult to induce. Whereas V(D)J mutations and selection in germinal centers are necessary to increase Ab affinity and specificity, B cells that become heavily mutated (>5%-8%) often exhibit reduced fitness by either lowered affinity or the acquisition of autoreactivity. In both instances, these mutant B cells are selected against and become a minor component of the humoral response or disappear altogether 31. The strong association of bnAbs with properties that are typically rare and in other types of antibodies, disfavored, is consistent with the absence or rarity of unmutated, naïve B cells capable of founding clonal lineages leading to bnAb production 31. This tolerance hypothesis 31, 41 explains not only why bnAb production is uncommon, but also why bnAb B cell antigen receptors are so characteristically atypical.

B-cell-lineage immunogen design is a strategy that has been proposed to overcome the disfavored status of HIV-1 bnAb clonal lineages (Figure 3) 31. B-cell-lineage immunogen design is based on the survival advantage exhibited by germinal center B cells expressing antigen receptors (BCR) with the highest affinity for antigen 60-62. By defining optimal immunogens to guide clonal evolution in germinal centers, B-cell lineages that would normally be disfavored can be promoted. Briefly, the process of B-cell-lineage design for HIV-1 bnAb production is: 1) bnAb clonal lineages from a patient or vaccine are isolated or inferred; 2) the recovered bnAbs are expressed as recombinant antibodies for Env-binding assays; 3) panels of recombinant Envs are expressed to screen for their binding affinities to each crucial branch in the bnAb lineage, and 4) those Envs or Env fragments that bind the highest affinity to the BCR at critical lineage branches are selected as immunogens. The serial administration of the selected Env immunogens would favor those V(D)J mutations and evolutionary trajectories that are necessary to generate bnAbs. The Env immunogens that optimally bind to the germline or unmutated common ancestor (UCA) become the vaccine prime, and those that bind to intermediate antibodies the first boosts, and those that bind to the mature antibodies become the final boosts 31.

Screening with heterologous Envs for B-cell-lineage immunogen design can be effective, but heterologous Envs frequently do not react with the UCAs of bnAb lineages 63, 64. This is likely because bnAbs lineages arise from the initial autologous Env antibody responses that are exquisitely specific for the infecting, founder virus Env 14, 65. Consequently, the ideal immunogens for initiating bnAb responses will likely be autologous founder virus Envs from those individuals that make bnAbs during the course of infection 14, or Env immunogens specifically engineered to bind to specific UCA BCRs 66.

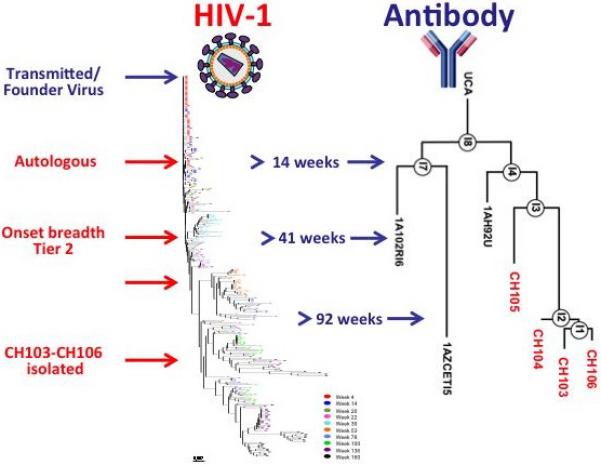

In the Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology-Immunogen Discovery (CHAVI-ID) program at Duke, 17 individuals followed from the time of transmission of HIV-1 to the development of bnAbs are being studied for the co-evolution of virus and immunity. The first of these individuals, CH505, has been extensively studied and the co-evolution of founder virus and bnAb clonal lineage maturation meticulously mapped (Figure 4). In doing so, the evolution of HIV-1 Env in response to antibody-mediated selection has been elucidated in unprecedented detail 14. Indeed, in CH505 a complete history of the sequential Env mutants that elicited bnAbs production was demonstrated, and now Envs and their sequence of administration can be recreated as serial immunogens to attempt to induce bnAb production by vaccination.

Fig. 4. Co-evolution of virus and a single antibody lineage in an HIV-1 seroconverter.

Mature CD4+-binding site antibodies CH103-106 were isolated from circulating memory B cells at week 136 after infection. Longitudinal sampling allowed inference and reconstruction of the evolution of the infecting viral sequence and of the specific neutralizing antibody lineage. B-cell gene sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were used to infer early intermediates (IA) and the unmutated common ancestor (UCA) antibody. The left part of the figure displays a phylogenetic tree of Env sequences derived from week 4 through week 160. The UCA and IA heavy chain sequences of the CH103 antibody lineages are shown alongside viral evolution. This antibody lineage evolved to gain high-affinity Env binding, and virus neutralization evolved from strain-specific autologous virus activity to cross-reactive neutralization of heterologous viruses 14.

The studies in CH505 revealed that bnAbs emerged only after the extensive diversification of the founder virus Env in successive waves of virus escape from the serial production of autologous neutralizing antibodies (the HIV-1arms race) (Figure 4). Thus, CH505 sequential Envs are being produced for trials in rhesus macaques and in humans to determine if similar bnAb lineages can be driven in a vaccination setting. Since it takes ~2 years for bnAbs to develop in chronically HIV-1 infected individuals 35, 48, 67, 68. We expect that multiple immunizations in macaques and humans will be necessary to drive bnAb development.

Various HIV-1 envelope immunogen types are now being developed that express epitopes for bnAbs and their precursors. There are three new structures proposed for the HIV-1 Env trimer 69-72 and the hope is that having the structure of a native Env trimer will be more antigenic and more immunogenic than previously used immunogens. In general, three categories of Env immunogens are in development—minimal immunogens that are fragments or scaffolded portions of HIV-1 Env neutralizing epitopes 66, 73, 74, intermediate Env immunogens such as monomeric Env gp120 11, and various forms of Env trimers 75. To date, however, not even those single immunogens with near native structures have been capable of inducing the immune system to generate bnAbs following vaccination.

It has been the view of the field that only ~10%-20% of HIV-1 chronically infected individuals are capable of making bnAbs 35, 48, 67, 68. More recently, however, screens of large numbers of infected individuals for their breadth of plasma neutralization has demonstrated that there are not polar extremes of neutralizing capacity, but rather a gradation of neutralization breadth in chronically infected populations 76. What is consistent is that those individuals who do make bnAbs, require years to do so. Early in HIV-1 infection, all infected individuals make autologous neutralizing Abs that are not different from patients that never generate bnAb. Thus, for vaccine trials, the concept is emerging that a successful vaccination for HIV-1, induction of bnAbs will require repetitive immunizations over a longer period of time than for currently licensed vaccines. This type of immunization poses the difficult question of how to design practical immunizations in order to replicate the evolution of the transmitted founder virus envelope over time of bnAb development.

The Way Forward

The way forward for HIV-1 vaccine development is centered on development of new immunogens to overcome diversity for T cell responses (mosaic and conserved immunogens), the induction of greater breadth and durability of immune responses induced in RV144 to improve on the minimal efficacy seen in RV144, and the development of vaccine strategies to recreate the Env swarms that generate bnAbs when they do occur in the setting of infection (Table 1). In essence, the job of the HIV-1 vaccine development field is to convert subdominant immune responses to become dominant responses -- a task never before required of, or successfully accomplished by, an infectious disease vaccine. Thus, HIV-1 vaccine work is breaking new ground in vaccinology, and success in development of an HIV-1 vaccine will herald success for other difficult to make broadly reactive vaccines such as for influenza and hepatitis C.

Table 1.

Major New Directions in HIV-1 Vaccine Research

| Induction of Protective T Cell Responses | Induction of Protective B Cell Responses |

|---|---|

| Defining strategies for overcoming T cell Immunity (mosaic, conserved immunogens) | Defining pathways of broadly neutralizing antibodies in HIV-infected individuals |

| Defining new conserved T cell epitopes for incorporation into T cell immunogens | Selecting immunogens that can bind to the naïve B cell receptors of broadly neutralized antibodies |

| Defining replicating vectors for T cell immunogens (attenuated cytomegalovirus, replicating adenovirus, poxviruses) | Selecting sequential and “swam” immunogens that can recapitate bnAb induction with vaccination |

| Design immunogens to induce T follicular helper cells to drive protective antibody responses | Design immunogens to improve on efficacy seen in RV144 canarypox prime clade B/E gp120 boost Thai trial |

Acknowledgments

Supported by CHAVI ID (UM1-AI100645) grant from the NIH, NIAID, Division of AIDS, and grant no. OPP1033098 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

Abbreviations used

- bnAb

broad neutralizing antibody

- Env

envelope

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus 1

- rAd5

recombinant adenovirus type 5

- CTLs

cytotoxic T cells

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- ADCC

antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- SIV

simian Immunodeficiency virus

- HCDR3s

immunoglobulin third heavy chain complementarity determining region

- KYNU

kynureninase

- BCR

B cell antigen receptor

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

- HC

heavy chain

- IA

intermediate antibody

- UCA

unmutated common ancestor antibody

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haynes BF, McElrath MJ. Progress in HIV-1 vaccine development. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8:326–332. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328361d178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton DR, Poignard P, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies present new prospects to counter highly antigenically diverse viruses. Science. 2012;337:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1225416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascola JR, Haynes BF. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies understanding nature's pathways. Immunol. Rev. 2013;254:225–244. doi: 10.1111/imr.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen SG, Piatak M, Jr., Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Gilbride RM, Ford JC, et al. Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature. 2013;502:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen SG, Sacha JB, Hughes CM, Ford JC, Burwitz BJ, Scholz I, et al. Cytomegalovirus vectors violate CD8+ t cell epitope recognition paradigms. Science. 2013;340:1237874. doi: 10.1126/science.1237874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santra S, Liao HX, Zhang R, Muldoon M, Watson S, Fischer W, et al. Mosaic vaccines elicit CD8+ T lymphocyte responses that confer enhanced immune coverage of diverse HIV strains in monkeys. Nat Med. 2010;16:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nm.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barouch DH, O'Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, et al. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat. Med. 2010;16:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nm.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barouch DH, Stephenson KE, Borducchi EN, Smith K, Stanley K, McNally AG, et al. Protective efficacy of a global HIV-1 mosaic vaccine against heterologous SHIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Cell. 2013;155:531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korber BT, Letvin NL, Haynes BF. T-cell vaccine strategies for human immunodeficiency virus, the virus with a thousand faces. J Virol. 2009;83:8300–8314. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00114-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:1275–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:2209–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaras GD, Ferrari G, Shen X, Alam SM, Liao HX, Pollara J, et al. Vaccine-induced plasma IgA specific for the C1 region of the HIV-1 envelope blocks binding and effector function of IgG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9019–9024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301456110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zolla-Pazner S, deCamp A, Gilbert PB, Williams C, Yates NL, Williams WT, et al. Vaccine-induced igg antibodies to V1V2 regions of multiple HIV-1 subtypes correlate with decreased risk of HIV-1 infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, et al. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013;496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, Karuna ST, Mulligan MJ, Grove D, et al. Efficacy trial of a DNA/Rad5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the step study): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomaras GD. Vaccine induced antibody responses in HVTN 505, a phase IIb HIV-1 efficacy trial.. AIDS Vaccine Meeting; Barcelona, Spain. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomaras GD, Haynes B. Advancing toward HIV-1 vaccine efficacy through the intersections of immune correlates. Vaccines. 2014;2:15–35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines2010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haynes BF, Liao HX, Tomaras GD. Is developing an HIV-1 vaccine possible? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:362–367. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833d2e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolland M, Edlefsen PT, Larsen BB, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Hertz T, et al. Increased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures in Env V2. Nature. 2012;490:417–420. doi: 10.1038/nature11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao HX, Bonsignori M, Alam SM, McLellan JS, Tomaras GD, Moody MA, et al. Vaccine induction of antibodies against a structurally heterogeneous site of immune pressure within HIV-1 envelope protein variable regions 1 and 2. Immunity. 2013;38:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P, Yates NL, Shen X, Bonsignori M, Moody MA, Liao HX, et al. Infectious virion capture by HIV-1 gp120-specific IgG from rv144 vaccinees. J Virol. 2013;87:7828–7836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02737-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu P, Williams LD, Shen X, Bonsignori M, Vandergrift NA, Overman RG, et al. Capacity for infectious HIV-1 virion capture differs by envelope antibody specificity. J Virol. 2014;88:5165–5170. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03765-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonsignori M, Pollara J, Moody MA, Alpert MD, Chen X, Hwang KK, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity-mediating antibodies from an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial target multiple epitopes and preferentially use the VH1 gene family. J. Virol. 2012;86:11521–11532. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01023-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yates NL, Liao HX, Fong Y, Decamp A, Vandergrift NA, Williams WT, et al. Vaccine-induced Env V1-V2 IgG3 correlates with lower HIV-1 infection risk and declines soon after vaccination. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:228ra239. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung AW, Alter G. Distinct HIV-specific antibody Fc-profiles in rv144 and vax003 vaccinees. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robb ML, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, Pitisuttithum P, Kaewkungwal J, Kunasol P, et al. Risk behaviour and time as covariates for efficacy of the HIV vaccine regimen ALAC-HIV (VCP1521) and AIDSVAX B/E: A post-hoc analysis of the thai phase 3 efficacy trial RV144. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2012;12:531–537. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roederer M, Keele BF, Schmidt SD, Mason RD, Welles HC, Fischer W, et al. Immunological and virological mechanisms of vaccine-mediated protection against SIV and HIV. Nature. 2014;505:502–508. doi: 10.1038/nature12893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letourneau S, Im EJ, Mashishi T, Brereton C, Bridgeman A, Yang H, et al. Design and pre-clinical evaluation of a universal HIV-1 vaccine. PLoS One. 2007;2:e984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santra S, Muldoon M, Watson S, Buzby A, Balachandran H, Carlson KR, et al. Breadth of cellular and humoral immune responses elicited in rhesus monkeys by multi-valent mosaic and consensus immunogens. Virology. 2012;428:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haynes BF, Alam SM. HIV-1 hides an achilles' heel in virion lipids. Immunity. 2008;28:10–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, Walker BD, Pereyra F, Cutrell E, et al. A method for identification of HIV gp140 binding memory B cells in human blood. J Immunol Methods. 2009;343:65–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray ES, Madiga MC, Hermanus T, Moore PL, Wibmer CK, Tumba NL, et al. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J. Virol. 2011;85:4828–4840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaebler C, Gruell H, Velinzon K, Scheid JF, Nussenzweig MC, Klein F. Isolation of HIV-1-reactive antibodies using cell surface-expressed gp160deltac(bal.). J Immunol Methods. 2013;397:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an african donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonsignori M, Hwang KK, Chen X, Tsao CY, Morris L, Gray E, et al. Analysis of a clonal lineage of HIV-1 envelope V2/V3 conformational epitope-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies and their inferred unmutated common ancestors. J Virol. 2011;85:9998–10009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Moody MA, Haynes BF. Role of immune mechanisms in induction of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haynes BF, Moody MA, Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Alam SM. Antibody polyspecificity and neutralization of HIV-1: A hypothesis. Hum Antibodies. 2005;14:59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang G, Holl TM, Liu Y, Li Y, Lu X, Nicely NI, et al. Identification of autoantigens recognized by the 2F5 and 4e10 broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:241–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verkoczy L, Diaz M, Holl TM, Ouyang YB, Bouton-Verville H, Alam SM, et al. Autoreactivity in an HIV-1 broadly reactive neutralizing antibody variable region heavy chain induces immunologic tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912914107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verkoczy L, Chen Y, Bouton-Verville H, Zhang J, Diaz M, Hutchinson J, et al. Rescue of HIV-1 broad neutralizing antibody-expressing B cells in 2F5 Vh x Vl knockin mice reveals multiple tolerance controls. J. Immunol. 2011;187:3785–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verkoczy L, Chen Y, Zhang J, Bouton-Verville H, Newman A, Lockwood B, et al. Induction of HIV-1 broad neutralizing antibodies in 2f5 knock-in mice: Selection against membrane proximal external region-associated autoreactivity limits T-dependent responses. J Immunol. 2013;191:2538–2550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennison SM, Stewart SM, Stempel KC, Liao HX, Haynes BF, Alam SM. Stable docking of neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region monoclonal antibodies 2f5 and 4e10 is dependent on the membrane immersion depth of their epitope regions. J. Virol. 2009;83:10211–10223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00571-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Zhang J, Hwang KK, Bouton-Verville H, Xia SM, Newman A, et al. Common tolerance mechanisms, but distinct cross-reactivities associated with gp41 and lipids, limit production of HIV-1 broad neutralizing antibodies 2F5 and 4E10. J Immunol. 2013;191:1260–1275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen X, Parks RJ, Montefiori DC, Kirchherr JL, Keele BF, Decker JM, et al. In vivo gp41 antibodies targeting the 2F5 monoclonal antibody epitope mediate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization breadth. J Virol. 2009;83:3617–3625. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02631-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen X, Dennison SM, Liu P, Gao F, Jaeger F, Montefiori DC, et al. Prolonged exposure of the HIV-1 gp41 membrane proximal region with l669s substitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5972–5977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pancera M, Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, Doria-Rose NA, McLellan JS, Bailer RT, Dai K, et al. Structural basis for diverse N-glycan recognition by HIV-1-neutralizing V1-V2-directed antibody pg16. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:804–813. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pancera M, Yang Y, Louder MK, Gorman J, Lu G, McLellan JS, et al. N332-directed broadly neutralizing antibodies use diverse modes of HIV-1 recognition: Inferences from heavy-light chain complementation of function. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, et al. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature. 2011;480:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sok D, Laserson U, Laserson J, Liu Y, Vigneault F, Julien JP, et al. The effects of somatic hypermutation on neutralization and binding in the PGT121 family of broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003754. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klasse PJ, Depetris RS, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Khayat R, Lee JH, et al. Influences on trimerization and aggregation of soluble, cleaved HIV-1 sosip envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 2013;87:9873–9885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01226-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Julien JP, Sok D, Khayat R, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Walker LM, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibody PGT121 allosterically modulates CD4 binding via recognition of the HIV-1 gp120 V3 base and multiple surrounding glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003342. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Murin CD, Julien JP, McBride R, et al. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science. 2011;334:1097–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meffre E, Milili M, Blanco-Betancourt C, Antunes H, Nussenzweig MC, Schiff C. Immunoglobulin heavy chain expression shapes the B cell receptor repertoire in human B cell development. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:879–886. doi: 10.1172/JCI13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonsignori M, Wiehe K, Grimm SK, Lynch R, Yang G, Kozink DM, et al. An autoreactive antibody from an SLE/HIV-1 patient broadly neutralizes HIV-1. J. Clinical Investigation. 2014 doi: 10.1172/JCI73441. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dal Porto JM, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ, Kelsoe G. Antigen drives very low affinity B cells to become plasmacytes and enter germinal centers. J Immunol. 1998;161:5373–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shih TA, Roederer M, Nussenzweig MC. Role of antigen receptor affinity in T cell-independent antibody responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:399–406. doi: 10.1038/ni776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shih TA, Meffre E, Roederer M, Nussenzweig MC. Role of BCR affinity in T cell dependent antibody responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ni803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao X, Chen W, Feng Y, Zhu Z, Prabakaran P, Wang Y, et al. Germline-like predecessors of broadly neutralizing antibodies lack measurable binding to HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: Implications for evasion of immune responses and design of vaccine immunogens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoot S, McGuire AT, Cohen KW, Strong RK, Hangartner L, Klein F, et al. Recombinant HIV envelope proteins fail to engage germline versions of anti-CD4BS bnAbs. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore PL, Gray ES, Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Nonyane M, Sheward DJ, et al. Evolution of an HIV glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibody epitope through immune escape. Nat Med. 2012;18:1688–1692. doi: 10.1038/nm.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jardine J, Julien JP, Menis S, Ota T, Kalyuzhniy O, McGuire A, et al. Rational HIV immunogen design to target specific germline B cell receptors. Science. 2013;340:711–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1234150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomaras GD, Binley JM, Gray ES, Crooks ET, Osawa K, Moore PL, et al. Polyclonal B cell responses to conserved neutralization epitopes in a subset of HIV-1-infected individuals. J Virol. 2011;85:11502–11519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05363-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sather DN, Armann J, Ching LK, Mavrantoni A, Sellhorn G, Caldwell Z, et al. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:757–769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meyerson JR, Tran EE, Kuybeda O, Chen W, Dimitrov DS, Gorlani A, et al. Molecular structures of trimeric HIV-1 Env in complex with small antibody derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:513–518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214810110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mao Y, Wang L, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Desormeaux A, Finzi A, et al. Molecular architecture of the uncleaved HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307382110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lyumkis D, Julien JP, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse PJ, et al. Cryo-em structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1484–1490. doi: 10.1126/science.1245627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, et al. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alam SM, Dennison SM, Aussedat B, Vohra Y, Park PK, Fernandez-Tejada A, et al. Recognition of synthetic glycopeptides by HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies and their unmutated ancestors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18214–18219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317855110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aussedat B, Vohra Y, Park PK, Fernandez-Tejada A, Alam SM, Dennison SM, et al. Chemical synthesis of highly congested gp120 V1V2 n-glycopeptide antigens for potential HIV-1-directed vaccines. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13113–13120. doi: 10.1021/ja405990z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanders RW, Derking R, Cupo A, Julien JP, Yasmeen A, de Val N, et al. A next-generation cleaved, soluble HIV-1 Env trimer, BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140, expresses multiple epitopes for broadly neutralizing but not non-neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003618. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hraber P, Seaman MS, Bailer RT, Mascola JR, Montefiori DC, Korber BT. Prevalence of broadly neutralizing antibody responses during chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2014;28:163–169. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moody MA, Yates NL, Amos JD, Drinker MS, Eudailey JA, Gurley TC, et al. HIV-1 gp120 vaccine induces affinity maturation in both new and persistent antibody clonal lineages. J Virol. 2012;86:7496–7507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00426-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moody MA, Zhang R, Walter EB, Woods CW, Ginsburg GS, McClain MT, et al. H3n2 influenza infection elicits more cross-reactive and less clonally expanded anti-hemagglutinin antibodies than influenza vaccination. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doyle-Cooper C, Hudson KE, Cooper AB, Ota T, Skog P, Dawson PE, et al. Immune tolerance negatively regulates B cells in knock-in mice expressing broadly neutralizing HIV antibody 4E10. J Immunol. 2013;191:3186–3191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]