Abstract

Introduction

The diagnosis of amyloid myopathy is delayed when monoclonal gammopathies are not detected on initial testing and muscle biopsies are nondiagnostic, and the EMG and symptoms can mimic an inflammatory myopathy.

Methods

Case report of a patient presenting with severe progressive muscle weakness of unclear etiology despite an extensive workup including two nondiagnostic muscle biopsies.

Results

Directed by MRI, a third biopsy revealed amyloid angiopathy and noncongophilic kappa light chain deposition in scattered subsarcolemmal rings and perimysial regions. A serum free light chain (FLC) assay revealed a kappa monoclonal gammopathy, which was not detected by multiple immunofixations.

Conclusions

The spectrum of immunoglobulin deposition in muscle is similar to other organs. It comprises a continuum that includes parenchymal amyloid deposition, amyloid angiopathy, and noncongophilic Light Chain Deposition Disease (LCDD). We recommend including the FLC assay in the routine investigation for monoclonal gammopathies. This case also highlights the value of MRI-guided muscle biopsy.

Keywords: amyloid, gammopathy, light chain deposition, MRI, myopathy

The classic phenotype of amyloid myopathy consists of mild proximal weakness, macroglossia, a hoarse voice, and muscle pseudohypertrophy or palpable muscle masses.1–3 A less common presentation has been described with more severe progressive weakness without macroglossia or pseudohypertrophy.1,2 Congophilic amyloid deposition can be seen in intramuscular blood vessel walls (i.e., amyloid angiopathy) and also encircling individual myofibers. As both of these findings represent amyloid within muscle, they are both considered amyloid myopathy. In other organs, a distinction is made between parenchymal pericellular amyloid deposition and amyloid angiopathy. A related disorder with interstitial pericellular deposition of noncongophilic light chains has been described in many other organs, often accompanied by amyloid deposition in blood vessels. Unlike intraparenchymal amyloid deposits which are more frequently lambda, light chain deposition disease (LCDD) is characterized most commonly by kappa deposition.4,5

The diagnosis of amyloid myopathy is often delayed, because monoclonal gammopathies are not detected on initial testing and muscle biopsies are frequently nondiagnostic. Additionally, the EMG findings, symptoms, and course can mimic an inflammatory myopathy.6,7 Although there is limited data on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in amyloid myopathy, published literature has stated that amyloidosis should not be included in the differential diagnosis of patients whose MRI scans show significant signal intensity changes within muscles.3

Here we present a patient with progressive proximal lower extremity muscle weakness who was finally diagnosed based on MRI findings atypical for amyloid myopathy, an MRI-directed muscle biopsy revealing unique pathology, and a serum free light chain (FLC) assay confirming a kappa monoclonal gammopathy despite multiple negative serum and urine immunofixations. We review similar published cases and suggest that the spectrum of immunoglobulin deposition in muscle may be similar to other organs, comprising a continuum of parenchymal amyloid deposition, amyloid angiopathy, and noncongophilic light chain deposition. This case also highlights the value of MRI-guided muscle biopsy and the evolving role for serum FLC assays in identifying monoclonal gammopathies.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 79-year-old man with a history of pelvic radiation for prostate cancer who is otherwise a generally healthy and fit active runner. He presented with approximately 18 months of progressive proximal lower extremity weakness which began with thigh myalgias while running, dyspnea on exertion, and distal sensory loss and paresthesias. At the time of initial examination, muscle power was MRC 5/5 throughout, except bilateral hip flexors, which were 4/5. The patient was only able to walk 2 flights of stairs or 300 feet without becoming short of breath. Serum CKs were mildly elevated (500s–600s U/L), and EMG was myopathic with increased spontaneous activity and myotonic potentials. Nerve conduction studies were normal. Tests for myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2, myotonia congenita, acid maltase deficiency, and thyroid disease were negative. Spinal MRI was unrevealing. He was given a presumptive diagnosis of inflammatory myositis. An initial biceps brachii muscle biopsy was interpreted as normal. Three months later, a rectus femoris muscle biopsy showed only mild type II atrophy and a half dozen COX-negative fibers of uncertain clinical significance. His symptoms were unresponsive to 18-weeks of high-dose prednisone, and weakness and dyspnea continued to progress. He began to use a walking cane and used his arms to push up from a seated position. Over the next several months, he became dependent on a wheelchair, with thigh abductors progressively weakening to MRC 2/5, knee extensors weakening to 4-/5, and hip flexors remaining 4/5 bilaterally.

Serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation was performed twice and revealed only hypogammaglobulinemia without a monoclonal abnormality. Thigh MRI showed T2 hyperintensity within many muscles, but sparing others. For example, there was strong T2 hyperintensity of the vastus medialis and lateralis, but the rectus femoris was spared (see Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Thigh MRI scans: (A) T2-weighted axial and (C) coronal images show diffuse hyperintensity within several muscles, with sparing of others, such as the rectus femorii (arrows). (B) T1-weighted axial images show negligible streaky fatty replacement within some muscles. Note that the subcutaneous tissues appear normal, without the pronounced T2-hyperintensity described in published cases of amyloid myopathy. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

The two essentially normal biopsies were from a very strong muscle (biceps brachii) and a muscle spared by MRI (rectus femoris). Based on the pattern of muscle involvement on thigh MRI and clinical quadriceps weakness, a left vastus medialis biopsy was performed. This third biopsy revealed scattered subsarcolemmal ring-like structures circumscribing individual myofibers which stained positively on oxidative and glycolytic stains, and excluded ATPase (see Fig. 2). On paraffin sections, these abnormal ringed fibers appeared to have three zones: an outer pale zone with perpendicular sarcomere banding and enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli, a middle thinner circumferentially oriented band, and an inner zone of relatively normal appearing sarcoplasm (Fig. 2E and F). There was perivascular congophilic amyloid deposition encasing virtually every blood vessel (i.e., amyloid angiopathy), but no amyloid was detected in the abnormal ringed structures surrounding individual myofibers (see Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Muscle biopsy pathology. Panels A–D show frozen sections of the same fibers, stained with: (A) hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), (B) NADH, (C) PAS, and (D) ATPase at pH9.4. Note that the entire fibers are dark on NADH, while the rings stain positively for PAS and exclude the ATPase stain. E,F: Higher magnification pictures of two abnormal fibers on paraffin sections, illustrating three apparent zones: (1) An outer pale ring with perpendicularly oriented sarcomeres (seen best in panel F), and enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli tending to cluster at the inner edge of the ring, (2) a thinner circumferentially oriented band, and (3) relatively normal appearing sarcoplasm in the middle of the fiber (cracking is artifactual). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

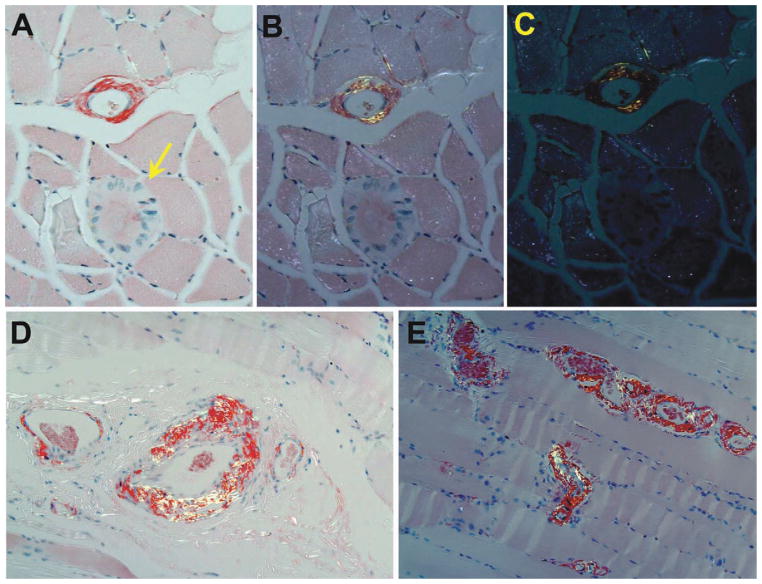

FIGURE 3.

Congo Red (CR) staining to visualize amyloid. Panels A–C show apple green birefringence in the walls of a blood vessel in the top half of the frame as a polarizing filter is rotated. Note that the abnormal ringed fiber in the lower half of the frame (arrow) is completely devoid of CR staining. (D,E)Mid-polarized images of the other intramuscular vessel with congophilia, characteristic of the ubiquitous amyloid angiopathy seen throughout the specimens from this MRI-guided biopsy. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Testing for transthyretin gene mutations was negative. A serum free light chain (FLC) assay was performed and revealed elevated free kappa greater than 8-times the upper limit of normal, normal lambda, and a K:L ratio of 14.9 (normal, 0.26–1.65). A third repeat serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, performed after the abnormal light chain assays, still showed only hypogammaglobulinemia without a monoclonal spike. A 24-h urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation was also normal.

Immunohistochemistry for kappa and lambda light chains revealed perimysial kappa light chain deposition in some regions of the biopsy. It was also seen within the abnormal subsarcolemmal rings encircling scattered myofibers and corresponding to the perivascular congophilic amyloid deposition (see Fig. 4). Lambda staining was negative (not shown). MRI of the pelvis showed a focal enhancing 1.2 cm lesion in the right iliac wing, which was not evident on the prior exam. A bone scan showed no evidence for abnormal activity in the lesion, and PET scan was also normal. Bone marrow biopsy revealed a monoclonal kappa restricted plasma cell population, which accounted for 5–10% of the marrow’s cellularity. Review of prior echocardiograms interpreted as normal revealed gradually increasing stiffness and thickening of the interventricular septum; it measured 1.12 cm in 2003, 1.3 cm in 2005, 1.39 cm in 2006, and 1.6 cm in 2009. He underwent treatment for light chain (AL) amyloidosis with bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2 weekly times 2 of every 3 weeks). He had no response based on light chain assays or clinical improvement in his weakness. The decision was made to add on lenaldiomide 15 mg daily for 14 of every 21 days. He received three cycles and had a 25% reduction in his kappa light chains but continued clinical deterioration. Unfortunately, he died of cardiac arrest 6 months after beginning treatment.

FIGURE 4.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for kappa light chains. (A) Prominent kappa light chain staining of blood vessels corresponding to congophilic amyloid. (B) Perimysial staining around a normal-appearing fiber (black arrow), and staining within the abnormal ring encircling an abnormal fiber (red arrow). (C,D) Magnified images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and kappa light chain IHC staining of the abnormal fiber in panel B. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

DISCUSSION

Our patient presented with progressive proximal lower extremity weakness and a myopathic EMG with myotonic discharges, which initially led to a diagnosis of inflammatory myopathy or muscular dystrophy. There was no pseudohypertrophy, palpable muscle masses, or dysarthria. Interestingly, in a retrospective chart review of 17 patients diagnosed with amyloid myopathy, Rubin and Hermann7 identified two patients with myotonic discharges, and five had complex repetitive discharges (CRDs) in proximal muscles. Myotonic and high-frequency repetitive discharges were noted in rare patients in another amyloid myopathy series as well.8

Although published data on MRI scans in amyloid myopathy are limited, several groups have concluded that classical MRI findings in amyloid myopathy comprise reticulation in the subcutaneous fat, with normal or negligible signal abnormalities within muscles.3,9–11 In fact, Metzler et al.3 suggested that amyloidosis should not be included in the differential diagnosis of patients whose MRI scans show significant signal intensity changes within muscles. In contrast, our patient’s MRI showed abnormal T2-hyperintensity within muscles while sparing certain muscles such as the rectus femoris, and the subcutaneous tissues appeared entirely normal. At least one other published case diagnosed as amyloid myopathy commented on an MRI with “evidence suggestive of atrophy and edema in the muscles of the hips, thighs, and calves…”.11

In our case, a third muscle biopsy, directed by the MRI findings, revealed perivascular amyloid deposition and abnormal ringed myofibers devoid of amyloid deposition. Pathologic descriptions of amyloid deposits in muscle include both vascular/ perivascular and interstitial/subsarcolemmal distributions, with deposits often seen in both locations.8,12 Similar ringed fibers have been described in cases of amyloid myopathy, and the rings frequently stain positively for amyloid (apple-green birefringence or rhodamine fluorescence on congo red [CR] staining).1,8,12 However, published series of amyloid myopathy also include many cases in which amyloid deposits were restricted to the blood vessels (i.e., amyloid angiopathy).2,6,8,13 The amyloid angiopathy in these cases can be missed by sampling error; indeed, cases of amyloid myopathy have been reported to require as many as four muscle biopsies to make the diagnosis. In one literature review, 19 cases were identified in which amyloid was missed on initial biopsy but was subsequently found on either repeat biopsy, review of the original tissue, or at autopsy.2 In 12 of these 19 cases, the amyloid was confined to intramuscular blood vessels, and in one case the amyloid was not visualized with congo red stain but was subsequently inferred by positive kappa light chain immunohistochemisty.14

In other organs, Light Chain Deposition Disease (LCDD) is defined as the deposition of noncongophilic material, which reacts with anti-immunoglobulin light chain staining.15 As in our patient, LCDD and AL-amyloidosis can be found in the same patient, with congophilic fibrillar amyloid deposited in blood vessel walls, and granular light chain deposits surrounding parenchymal cells or in liver sinusoidal walls.4,16 Ultrastructurally, the light chain depositions have a fine granular appearance in contrast to the fibrillar appearance of amyloid.4,17 Unfortunately, we did not have tissue processed for EM from our case. LCDD has been described surrounding parenchymal cells in numerous organs, most commonly liver, heart, and kidney, but also adrenal glands, spleen, pancreas, muscle, choroid plexus, and nerve.4,16–19 In LCDD, the light chain is more commonly kappa, while in AL amyloidosis, it is more frequently lambda.4,5,18,20 In both their own series of 13 patients and a review of 43 published cases of amyloid myopathy, Spuler et al.8 found that the light chain dysproteinemia in amyloid myopathy is most commonly lambda.

The abnormal ringed myofibers in our case stained for kappa light chains and exhibited no congophilia. A few other cases in the literature have reported kappa light chain deposits around muscle fibers that are negative on congo red stains. A case described by Chapin et al.2 had intense congophilia in vessel walls and to a lesser extent in the endomysium, but there were also scattered fibers with granular basophilic material sparing the center of the fibers, which were ringed by nuclei with prominent nucleoli, like our case. The unusual ringed fibers did not contain amyloid per EM staining. Delaporte et al.14 reported a case with similar findings, in which a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells was not identified until two years after the first muscle symptoms, and suggested that the pathology warrants classification as a case of “IgG light chain disease” rather than amyloid myopathy. Kasahara et al.17 described a 40-year-old man with widespread LCDD who initially presented with renal failure but also had proximal muscle atrophy, and autopsy showed kappa light chain deposits (granular on EM) in many organs including muscle, without amyloid deposition.

Both AL amyloidosis and LCDD can occur in the presence or absence of clinical myeloma, and serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation can be negative in as high as 30% of patients, even on repeat examinations.4,15,17 Serum free immunoglobulin light chain (FLC) assays can detect FLCs to 2–4 mg/L, in contrast to immunofixation, which detects concentrations of 100–150 mg/L. Additionally, the test provides a ratio of kappa to lambda light chains; a specific indicator of monoclonal production that is prognostic in multiple myeloma and a risk factor for progression of monoclonal gammopathies of unknown significance (MGUS) to clinically significant pathology.21,22 The FLC assay uses polyclonal latex-conjugated anti-FLC antibodies, and binding is quantified with automated nephelometry or turbidometry.21,23 Pratt21 points out that a paraprotein is only detectable in approximately 50% of patients with AL amyloidosis, but the serum FLC assay gives an abnormal quantification in 90–95% and an abnormal ratio in 90%. Combining the serum FLC assay and serum IFE identified 109/110 AL amyloidosis patients in a series by Katzmann et al.24 The serum FLC assay has been incorporated into the response criteria for both multiple myeloma (MM) and AL amyloidosis.25,26

In other organs, the distinction between LCDD and amyloidosis is suggested to have clinical and prognostic significance, though clearly these presentations represent a continuum and both findings may be present in the same patient.4,15,16 Based on the limited published literature in muscle, it is difficult to determine retrospectively whether there may be a correlation with phenotype. In many cases, patients with intramuscular amyloid angiopathy without interstitial/subsarcolemmal amyloid have been classified as amyloid myopathy without further investigation. Certainly, our patient would fit the less common presentation of amyloid myopathy with severe progressive proximal weakness mimicking a myositis, without pseudohypertrophy or palpable muscle masses. Whether features of the clinical phenotype relate to the spectrum of pathologic light chain deposition in muscle awaits the identification of more cases, ideally facilitated by MRI and FLC assays.

In summary, we describe a case of pericellular kappa-restricted light chain deposition in muscle accompanied by amyloid angiopathy, comparable to LCDD described in other organs. The MRI features, clinical course, EMG, and lab testing all initially pointed toward an inflammatory myopathy. This case illustrates the importance of using MRI findings to help choose biopsy sites when abnormalities are detected on imaging studies. It is unclear whether the significant T2 hyperintensity seen on his thigh MRI is a unique feature of light chain deposition in muscle, but it certainly points out that similar findings on MRI do not rule out pathologic immunoglobulin deposition in muscle, in contrast to prior reports.3,10 We wonder whether similar cases may have been mis-diagnosed as inflammatory myopathies if amyloid was not seen on initial biopsies and immunofixations were unrevealing (as is often the case). Therefore, we believe that the FLC assay should be added to the evaluation when investigating for gammopathies.

Abbreviations

- FLC

free light chain

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LCDD

light chain deposition disease

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

References

- 1.Nadkarni N, Freimer M, Mendell JR. Amyloidosis causing a progressive myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:1016–1018. doi: 10.1002/mus.880180914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapin JE, Kornfeld M, Harris A. Amyloid myopathy: characteristic features of a still underdiagnosed disease. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:266–272. doi: 10.1002/mus.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzler JP, Fleckenstein JL, White CL, Haller RG, Frenkel EP, Greenlee RG. MRI evaluation of amyloid myopathy. Skeletal Radiol. 1992;21:463–465. doi: 10.1007/BF00190993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganeval D, Noel LH, Preud’homme JL, Droz D, Grunfeld JP. Light-chain deposition disease: its relation with AL-type amyloidosis. Kidney Int. 1984;26:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan B, Ramirez-Alvarado M, Sikkink L, Golderman S, Dispenzieri A, Livneh A, et al. Free light chains in plasma of patients with light chain amyloidosis and non-amyloid light chain deposition disease. High proportion and heterogeneity of disulfide-linked monoclonal free light chains as pathogenic features of amyloid disease. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandl LA, Folkerth RD, Pick MA, Weinblatt ME, Gravallese EM. Amyloid myopathy masquerading as polymyositis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:949–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin DI, Hermann RC. Electrophysiologic findings in amyloid myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:355–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199903)22:3<355::aid-mus8>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spuler S, Emslie-Smith A, Engel AG. Amyloid myopathy: an under-diagnosed entity. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:719–728. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz B, Leja S, Melles RB, Press GA. Amyloid ophthalmoplegia: ophthalmoparesis secondary to primary systemic amyloidosis. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1989;9:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hull KM, Griffith L, Kuncl RW, Wigley FM. A deceptive case of amyloid myopathy: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1954–1958. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1954::AID-ART333>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuomaala H, Karppa M, Tuominen H, Remes AM. Amyloid myopathy: a diagnostic challenge. Neurol Int. 2009;1:24–26. doi: 10.4081/ni.2009.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prayson RA. Amyloid myopathy: clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karacostas D, Soumpourou M, Mavromatis I, Karkavelas G, Poulios I, Milonas I. Isolated myopathy as the initial manifestation of primary systemic amyloidosis. J Neurol. 2005;252:853–854. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaporte C, Varet B, Fardeau M, Nochy D, Ract A. In vitro myotrophic effect of serum kappa chain immunoglobulins from a patient with kappa light chain myeloma and muscular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:922–927. doi: 10.1172/JCI112681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buxbaum J, Gallo G. Nonamyloidotic monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease: light-chain, heavy-chain, and light- and heavy-chain deposition diseases. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faa G, Van Eyken P, De Vos R, Fevery J, Van Damme B, De Groote J, et al. Light chain deposition disease of the liver associated with AL-type amyloidosis and severe cholestasis: a case report and literature review. J Hepatol. 1991;12:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90913-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasahara N, Tamura H, Matsumura O, Nagasawa R, Suzuki Y, Ohgida T, et al. An autopsy case of light-chain deposition disease. Intern Med. 1994;33:216–221. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyoda M, Kajita A, Kita S, Osamura Y, Shinoda T. An autopsy case of diffuse myelomatosis associated with systemic kappa-light chain deposition disease (Lcdd) - a patho-anatomical, immunohistochemical and immunobiochemical study. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1988;38:479–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1988.tb02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grassi M, Clerici F, Perin C, Borella M, Mangoni A, Gendarini A, et al. Light chain deposition disease neuropathy resembling amyloid neuropathy in a multiple myeloma patient. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1998;19:229–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02427609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picken MM, Gallo G, Buxbaum J, Frangione B. Characterization of renal amyloid derived from the variable region of the lambda light chain subgroup II. Am J Pathol. 1986;124:82–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratt G. The evolving use of serum free light chain assays in haematology. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradwell AR. Serum free light chain measurements move to center stage. Clin Chem. 2005;51:805–807. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.048017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradwell AR, Carr-Smith HD, Mead GP, Tang LX, Showell PJ, Drayson MT, et al. Highly sensitive, automated immunoassay for immunoglobulin free light chains in serum and urine. Clin Chem. 2001;47:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzmann JA, Abraham RS, Dispenzieri A, Lust JA, Kyle RA. Diagnostic performance of quantitative {kappa} and {lambda} free light chain assays in clinical practice. Clin Chem. 2005;51:878–881. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.046870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, Fermand JP, Hazenberg BP, Hawkins PN, et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:319–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durie BGM, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]