Abstract

Although inhibition plays a major role in the function of the mammalian neocortex, the circuit connectivity of GABAergic interneurons has remained poorly understood. The authors review recent studies of the connections made to and from interneurons, highlighting the overarching principle of a high density of unspecific connections in inhibitory connectivity. Whereas specificity remains in the subcellular targeting of excitatory neurons by interneurons, the general strategy appears to be for interneurons to provide a global “blanket of inhibition” to nearby neurons. In the review, the authors highlight the fact that the function of interneurons, which remains elusive, will be informed by understanding the structure of their connectivity as well as the dynamics of inhibitory synaptic connections. In a last section, the authors describe briefly the link between dense inhibitory networks and different interneuron functions described in the neocortex.

Keywords: inhibition, networks, GABAergic, interneurons, connectivity

The mammalian neocortex is the largest part of the brain and is responsible for numerous functions including complex cognitive functions. Crucial to understanding how the cortex processes information is a complete description of the neurons composing its microcircuits, including the structural and functional dynamic characteristics of the connections between them. The cortical microcircuit is composed of a majority of excitatory pyramidal cells (PCs), the output neurons, and a large variety of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. Most studies have focused on the excitatory PCs, but over the past decades there has been a growing body of evidence supporting the important role of inhibitory cells in cortical functions. The great diversity that interneurons exhibit in electrophysiological properties, anatomical characteristics, neuropeptide expression, and subcellular compartment targeting has made it difficult to study them in a systematic manner. Some interneuron classifications have been recently attempted (Ascoli and others 2008; Markram and others 2004), but the list of potential new interneuron subtypes is growing and the fundamental definition of a subtype remains in flux. The variety of interneurons might reflect a division of labor for the function of inhibition in cortical neuronal networks. Therefore, it is critical to understand how interneurons integrate into neuronal circuits in the neocortex to determine how they could influence computation, but one also must consider that the different subtypes may have independent functions.

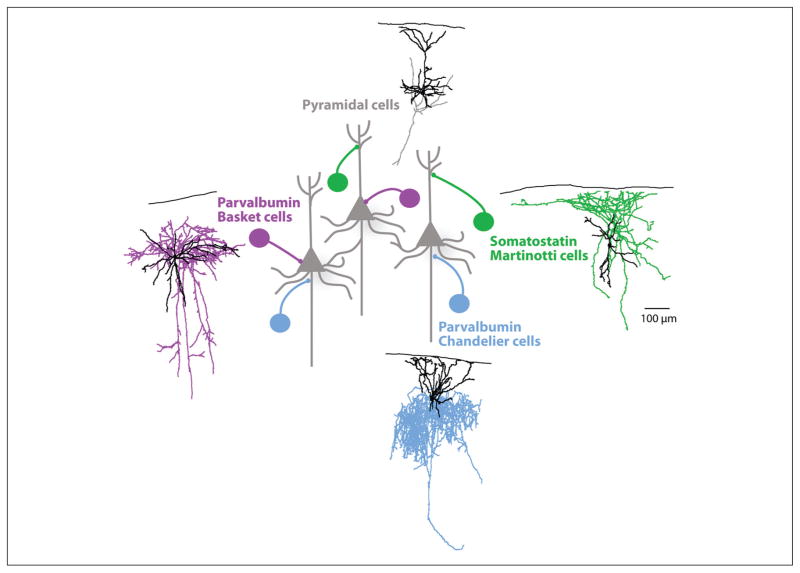

GABAergic interneurons contact a large majority of the surface area of PCs, across the entire dendritic tree, the soma, and the axon initial segment. In fact, inhibitory synapses on the different cellular subcompartments are mediated by different subtypes of interneurons (Somogyi and others 1998). The main subtypes of interneurons mediate either perisomatic inhibition, which may control the output of PCs, or dendritic inhibition, which locally controls the inputs of the PCs (Fig. 1). Perisomatic inhibition is mainly mediated by parvalbumin (PV)- or cholecystokinin (CCK)-containing basket cells, and PV-expressing Chandelier cells, also called axo-axonic cells, which specifically contact the axon initial segment. Perisomatic inhibition is thought to control the input/output gain of PCs (Pouille and others 2009). Interneurons responsible for dendritic inhibition are mainly somatostatin (SOM)-positive interneurons, which predominantly are Martinotti cells (McGarry and others 2010). Dendritic inhibition controls local integration of inputs (Murayama and others 2009) and is able to mediate a strong disynaptic inhibition in cortical circuits (Kapfer and others 2007; Silberberg and Markram 2007).In this review, we address inhibitory connectivity in cortical networks and how this connectivity might reflect the potential function of GABAergic interneurons.

Figure 1.

Different pyramidal cell subcompartments targeting GABAergic interneurons. Representation of the different interneuron subtypes based on their pyramidal cell (grey) subcompartment targeting. The parvalbumin-positive basket cells (purple) target the perisomatic region, somatostatin-positive Martinotti cells (green) target the dendrites, and chandelier cells (blue) the axon initial segment. A representative morphological reconstruction of each neuronal subtype from layer 2/3 illustrates their dendritic (black) and axonal (colored) arborizations.

Structure of Inhibitory Connectivity

Since the times of Cajal, it was known that connections of PCs can be long range, within the cortex or projecting to downstream structures, whereas inhibitory interneurons, originally known as “short axon cells,” contact mainly local targets (Ramon y Cajal 1899). As previously mentioned, excitatory connectivity has been the most studied in cortical circuits, and although some studies find great specificity in cortical connections (Thomson and Lamy 2007), others have proposed that cortical neurons connect with others without any specificity, forming a network on which activity-dependent developmental rules could sculpt mature circuits (Kalisman and others 2005; Stepanyants and others 2002). The logic of inhibitory connectivity is similarly split on this issue, with evidence in some cases arguing for specificity whereas other evidence points to unspecific inhibitory connectivity patterns.

Input and Output Connectivity of Interneurons

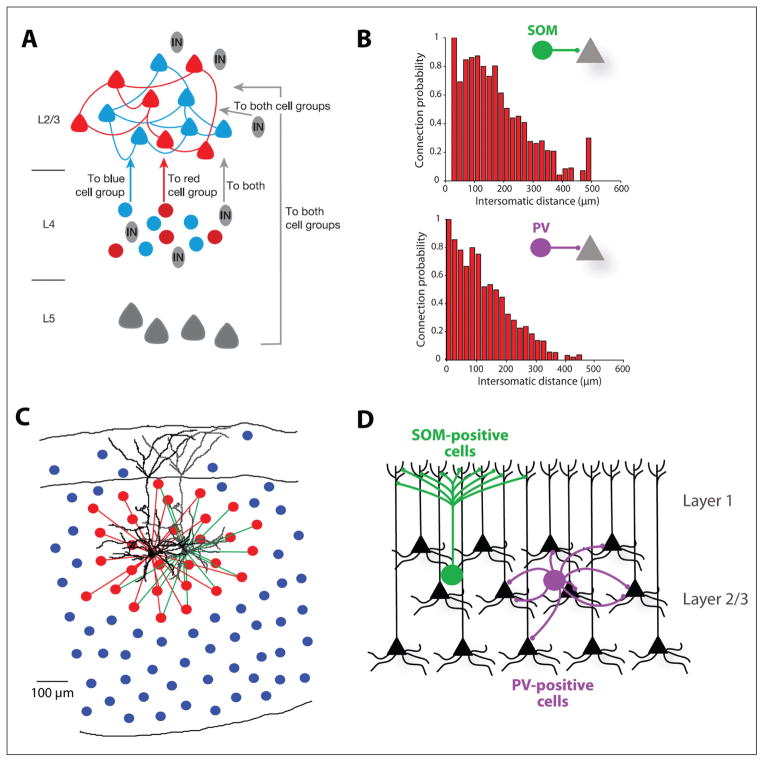

Most of the studies addressing the interneuron integration in cortical microcircuits have focused on characterizing excitatory inputs onto interneurons. The organization of excitatory inputs to interneurons have been first explored with one-photon photostimulation experiments and paired recordings, and although some studies find distinct subnetworks, others do not, depending on the interneuron subtype considered (Otsuka and Kawaguchi 2009; Thomson and Lamy 2007; Yoshimura and Callaway 2005). In this context, subnetworks refer to the probability for connected neurons, assumed to be part of the same functional network, to share more common inputs than unconnected neurons, presumably part of different networks (Fig. 2A). More specifically, although connected pairs of SOM-positive and PCs did not share more common excitatory inputs than unconnected ones, FS cells (presumably PV positive) that were reciprocally connected to PCs shared more common input from excitatory sources than those that were not (Yoshimura and Callaway 2005). In addition, FS cells preferentially targeted PCs that provided reciprocal excitatory connections (Yoshimura and Callaway 2005). On the contrary, layer 2/3 PCs seem to innervate connected pairs of SOM-PCs interneurons in layer 5 preferentially but not PV-PCs pairs (Otsuka and Kawaguchi 2009). This could indicate that the recruitment of distinct inhibitory subtypes by excitatory circuits and the formation of specific subnetworks might depend on the layers or cortical areas considered.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory connectivity. (A) Schematic diagram representing the organization of cortical connections between layer 4 and layer 2/3 somatosensory cortex. Excitatory connections define groups of selectively interconnected neurons (red or blue) whereas interneurons (IN) do not respect the fine-scale interconnected cell groups defined by excitatory connections and contact both blue and red pyramidal cell (PC) subpopulations (From Yoshimura and others 2005 with permission). (B) Plots of the connection probability between somatostatin (SOM)-positive interneurons in frontal cortex layer 2/3 and parvalbumin (PV)-positive interneurons in frontal and somatosensory cortex layers 2/3 and 5 and PCs depending on the intersomatic distances. The probability of connectivity from interneurons to PCs is very high when the intersomatic distance between the neurons is low and drops off as the intersomatic distance increases (Adapted from Fino and Yuste 2011 and Packer and Yuste 2011). (C) Schematic representation of a dense connectivity of inhibitory inputs from interneurons to PC (connected interneurons in red and unconnected interneurons in blue). The two PCs illustrate that this applies for connected or unconnected PCs (Adapted from Fino and Yuste 2011). (D) Laminar model of interneuron projections to PCs allowing specific targeting of PC subcompartments: by projecting to layer 1, where only distal dendrites are present, SOM interneurons interneurons avoid contacting somata and proximal dendrites of PCs. PV interneurons, on the other hand, project to layer 2/3 and thus avoid contacting distal dendrites (Adapted from Packer and others, in press).

In terms of the output of interneurons, most studies have addressed inhibitory inputs from interneurons to PCs using patch-clamp paired recordings, describing a wide range of connectivity, varying from 20% to 60% (Thomson and Lamy 2007). Recently, we described a very high inhibitory connection probability (up to 70% within 200 μm around the PCs, and even higher at closer distances) revealed by two-photon rubi-glutamate uncaging (Fino and others 2009) on SOM cells and PV cells (Fino and Yuste 2011; Packer and Yuste 2011) (Fig. 2B). This technique allowed us to address inhibitory connectivity at a high throughput scale, testing up to 80 interneuron-PC connections within the same experimental conditions. The dense inhibition observed in these experiments indicates a strong local control of circuit excitability by both subtypes of interneurons. In addition, comparison between connected and unconnected pairs of PCs did not reveal higher connection probability for connected PCs, indicating a lack of specificity in the local inhibitory connectivity (Fino and Yuste 2011; Packer and Yuste 2011; Yoshimura and Callaway 2005) (Fig. 2C). Therefore, unlike excitatory circuits (Brown and Hestrin 2009), interneurons do not appear to discriminate postsynaptic partners based on identity. Additionally, this dense connectivity was consistent throughout development for both SOM and PV cells as well as similar throughout cortical areas and layers for PV cells. A recent optogenetic study confirmed the strong local bias for inhibitory connections across all GABAergic neurons (Katzel and others 2011). Local inhibition would therefore highly connect the PCs in order to balance excitation with the fewer numbers of interneurons (Fig. 2C).

A final aspect of the anatomical connectivity of interneurons is their subcellular targeting of PCs, a property that varies across interneurons subtypes. SOM cells are most dendrite targeting whereas PV cells prefer the perisomatic regions. Indeed, many PV cells are “basket” cells, a term that emerged from their axons that appear to wrap somata (DeFelipe and Fairen 1982). At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that even these so-called soma-targeting cells only make 30% of their contacts directly onto somas (Kisvárday 1992). Although the apparent specificity of these connections leads intuitively to the hypothesis of molecular markers for different regions of a PC, our recent work has hinted that subcellular targeting of both PV and SOM cells could instead result from their laminar targeting by their axons, given that different layers have different proportion of PC somata and dendrites (Packer and others, in press; Fig. 2D). In this view, Peters’s rule, that is, the mere overlap of axons and dendrites, could explain the spatial feature of the connectivity maps. At the same time, axo-axonic Chandelier cells specifically target the axon initial segment, an extreme specificity that indicates the presence of precise molecular markers at least for this portion of the PC.

Laminar and Area Differences in Inhibitory Connectivity

Numerous anatomical and physiological studies have revealed both columnar and laminar organization of cortical connectivity (Douglas and Martin 2004; Mountcastle 1982), giving rise to the idea that the neocortex is composed of repetitions of a basic modular unit, performing essentially the same computation on different inputs. Most studies on columnar organization have been performed in sensory cortices such as somatosensory or visual cortex where this organization is anatomically visible. But at the same time, there are structural differences among cortical areas and species, so each cortical region could still have a specific, dedicated circuit. Indeed, the distribution of subtypes of interneurons as defined by molecular markers seems to vary across cortical areas (Xu and others 2010). For example, in somatosensory cortex, within a column corresponding to a barrel, the sources of inhibition vary depending on the layers, with “hot zones” of inhibition in layers 2 and 5A (Meyer and others 2011). Although dense connectivity of interneurons-PCs has been observed in different cortical areas and layers (Packer and Yuste 2011), these data raise the possibility that there could be major differences in inhibitory microcircuits throughout the neocortex.

Functional Inhibitory Connectivity

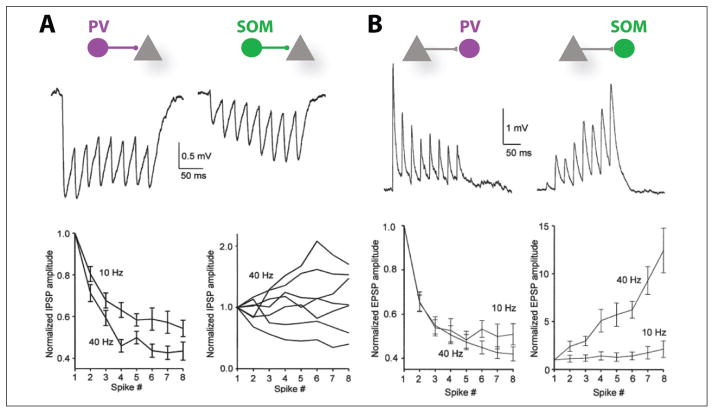

In addition to the anatomical properties, the functional properties of the inhibitory connections such as synaptic weight and dynamics play a central role in the function of inhibition and could craft the structural network of inhibitory connections into functional subspaces. Indeed, PCs and interneurons receive numerous excitatory or inhibitory synapses but each may have a different weight and therefore a different functional effect on inputs and outputs. Ideally, one would like to compare the synaptic strength of all inputs and outputs of all the interneurons within the same cortical area. This information is experimentally unavailable but would be necessary for a complete understanding of functional inhibitory connectivity. Moreover, similar to excitatory synapses, inhibitory synapses can also display experience-dependent long-term plasticity (Lamsa and others 2010) as well as physically reorganize (Chen and others 2012) in ways that will critically influence the weight of interneurons onto PCs. In addition, synaptic dynamics, such as short-term plasticity, also has consequences in the control of PC activity by interneurons. PV-PC connections display a strong short-term depression in response to a train of action potentials when contacting PCs, whereas SOM cells display a moderate facilitation or depression (Beierlein and others 2003) (Fig. 3). The excitatory synaptic dynamics onto interneurons also differ depending on interneuron subtype. PC-PV synapses display short-term depression whereas PC-SOM synapses a short-term potentiation, in both local cortical and thalamocortical synapses (Beierlein and others 2003; Tan and others 2008). PV cells are therefore efficiently activated as soon as PCs fire, mediating a fast strong inhibition that rapidly decreases, whereas SOM cells are slowly and increasingly recruited and have a growing inhibitory effect if PC activity is sustained. Thus, PV and SOM cells could implement complementary roles in the regulation of cortical network excitability.

Figure 3.

Short term-dynamics between interneurons and excitatory neurons. (A) Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) evoked by parvalbumin (PV) cells and somatostatin (SOM) cells onto pyramidal cells (PCs) have distinctive short-term dynamics. Representative IPSPs for each interneuron-PC connections in response to a 40-Hz train (8 spikes) and summary graph of response amplitudes (normalized to the first IPSP) during trains evoked at various frequencies. (B) Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) recorded from PV and SOM interneurons have distinctive short-term dynamics. Representative EPSPs for each interneuron-PC connections in response to a 40-Hz train (8 spikes) and summary graph of response amplitudes (normalized to the first EPSP) during trains evoked at 10 or 40 Hz. For connections in both directions, PV cells display a strong short-term depression whereas SOM interneurons display short-term facilitation (From Beierlein and others 2003 with permission).

Altogether, the functional state of the inhibitory network could vary, not only from layer to layer but also from interneuron to interneuron and as function of time. Within a given layer, a local dense inhibition could build a connectivity pattern in which neighboring neurons have largely overlapping but not exactly similar connections, and each of them could be altered differentially. This could mean that each interneuron would have its own input and output territory and adapt the strength of inputs and outputs depending on learning rules and previous activity patterns.

Inhibitory Neuronal Networks

Connections between inhibitory cells are also crucial to understanding how inhibitory circuits are organized. We leave aside connections mediated by gap junctions that allow the formation of electrically coupled inhibitory networks that have been extensively described elsewhere (Hestrin and Galarreta 2005) and instead focus on chemical synapses. Several studies performed with double patch-clamp recordings described that PV-positive interneurons contact other PV-positive or SOM-positive interneurons with a high connectivity rate of almost 80% (Galarreta and Hestrin 2002). The connectivity from SOM-positive interneurons to PV-positive interneurons is similar, but surprisingly, chemical connections are almost nonexistent for SOM-positive interneurons among themselves (Gibson and others 1999; Hu and others 2011; Ma and others 2012). This would suggest that there are inhibitory networks formed by PV-positive interneurons and by both PV- and SOM-positive cells but none comprising only SOM-positive interneurons. This could have functional consequences in the regulation of inhibitory network activity and their influence on excitatory microcircuits. For example, recent work has revealed that fear conditioning in auditory cortex is mediated by a disinhibitory circuit based on the shutdown of PV cells in layer 2/3 by interneurons in layer 1 (Letzkus and others 2011). Additionally, both SOM and PV cells generate large numbers of autaptic connections (Tamás and others 1997). Such self-regulatory circuits that inhibit inhibition may be vital to understanding the computational role of inhibitory to inhibitory connections.

Potential Function of Interneurons

It is still unclear what role interneurons play in the cortical circuit. In this final section, we will review some hypotheses and discuss them within the framework of our recent data on the dense structural connectivity of local interneuronal circuits (Fino and Yuste 2011; Packer and Yuste 2011).

Generation of Connectivity Motifs and PC Synchrony

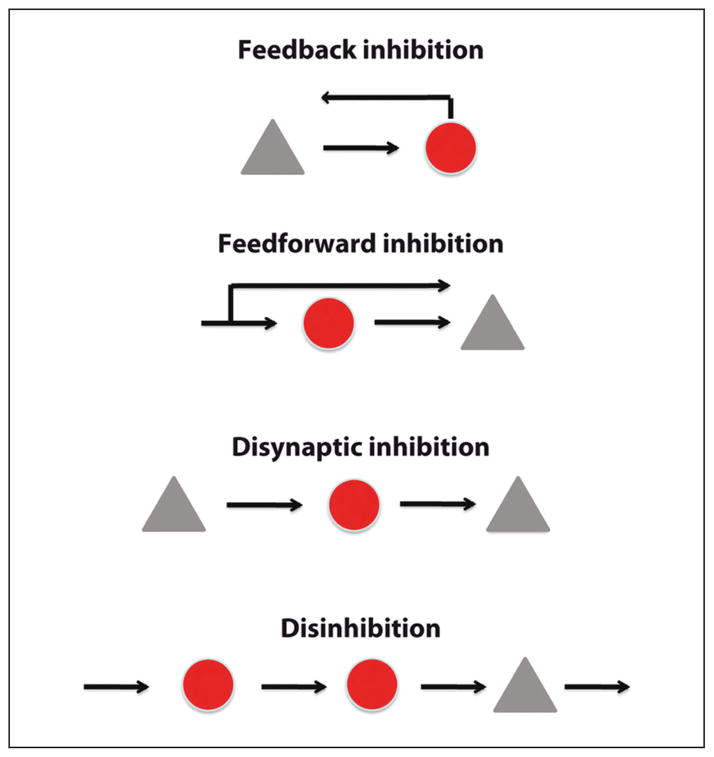

A first hypothesis could be that interneurons carve out subcircuits within the PC networks. Indeed, inhibitory neurons take part in motifs, or repeated circuit patterns. Feedforward inhibition, feedback inhibition, disynaptic inhibition, and disinhibition have all been observed at a high frequency throughout the neocortex and other anatomical areas of the brain (Fig. 4). The high probability of interneuron connectivity may serve to functionally guarantee the presence of these motifs among all excitatory neurons, particularly because inhibitory circuits are easy to recruit. For example, functional studies showed that SOM-expressing interneurons are efficiently recruited by network activity (Kapfer and others 2007), to the point that even the firing of a single PC can activate them (Kozloski and others 2001). Martinotti cells, the main SOM-expressing interneuron subtype, mediate strong disynaptic inhibition between PCs throughout the cerebral cortex (Berger and others 2009), with higher prevalence than monosynaptic connections between PCs (Silberberg and Markram, 2007). This powerful inhibition is mediated by few interneurons, which are able to generate strongly correlated membrane fluctuations and synchronous spiking between PCs (Berger and others 2010).

Figure 4.

Connectivity motifs involving interneurons. Schematic representation of different connectivity configurations allowing various functions described for inhibitory interneurons: feedback, feedforward, or disynaptic inhibition and disinhibition. Pyramidal cells are in grey and interneurons in red.

Tuning Properties of Interneurons

Another potential function of interneurons is the control of the functional properties of PCs. Consistent with the lack of specificity in dense inhibitory outputs in cortical microcircuits, interneurons in layer 2/3 of visual cortex are broadly tuned to the orientation of a stimulus (Hofer and others 2011; Kerlin and others 2010; Niell and Stryker 2008; Sohya and others 2007, but see Runyan and others 2010). This implies that interneurons are not involved in the generation of specific receptive field properties (Fig. 5A). In addition, neocortical interneurons also receive input from neurons tuned to different orientations (Bock and others 2011), providing an anatomical basis for the observation of broad tuning in interneurons (Fig. 5B). This indicates that local anatomical inputs to interneurons may not be organized on a functional basis in visual cortex. Therefore, dense inhibitory innervation could serve instead to simply adjust the gain of PCs, perhaps even with no further computational goal.

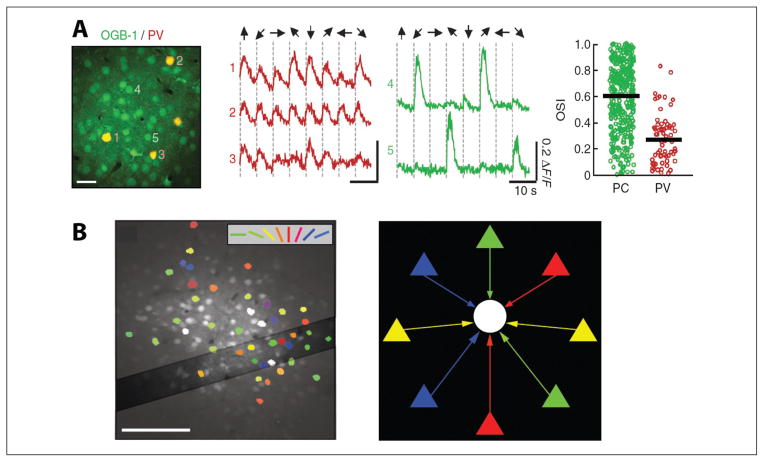

Figure 5.

Dense inhibitory connectivity related to interneuron function. (A) Left: OGB-1–labeled neurons, including four parvalbumin (PV) neurons (red) in layer 2/3. Middle panel: average calcium traces from three PV neurons (red) and two parvalbumin-negative neurons (putative pyramidal cells [PCs], green) during stimulation with episodically presented drifting gratings (eight different drifting grating directions shown at the top). Orientation selectivity index (OSI) for PCs (green) and PV interneurons (red): OSI shows highly selective, sharply tuned PCs, whereas PV cells are broadly tuned and nonselective. This indicates that PV cells are not involved in orientation tuning of PCs in visual cortex (From Hofer and others 2011 with permission). (B) Cell-based visual orientation preference map in the mouse visual cortex from in vivo two-photon calcium imaging. Visually responsive cells are colored according to their estimated preferred orientation (color coding shown at top). Broadly tuned cells are shown in white and correspond to GABAergic interneurons. Right: Schematic representation of diverse input to inhibitory interneurons. Excitatory pyramidal cells (triangles) with different preferred orientations (different colors) provide input to an inhibitory interneuron (white circle) (From Bock and others 2011 with permission).

Network-Level Control: Balance, Gain Control, Temporal Processing, Gating, and More

Finally, inhibitory connections may serve to generate and/or terminate particular network states. In particular, the role of SOM cells in controlling states of the neural network could be different than PV cells. PV cells, with strong activation and depressing synapses, could shut off and thus allow for the development of excitatory attractor states (Cossart and others 2003), whereas SOM cells, recruited later but strongly (because of facilitating synapses), could mediate inhibition, which leads to the end of attractor states (Krishnamurthy and others 2012). Indeed, during cortical UP states, PV cells fire more at the beginning, whereas SOM cells are responsible for terminating the UP state and initiating the transition to the DOWN state (Fanselow and others 2008). The different interneuron subtypes thus may play complementary roles in cortical computation and control of activity states.

In addition, the differential distribution of inhibition throughout cortical columns could have a crucial role in cortical information coding. Indeed, the zones of inhibition in layer 2/3 of barrel cortex agree with in vivo recordings activity during whisking activity in mice in which layer 2/3 shows sparse activity (O’Connor and others 2010). The dense inhibition in layer 2/3 could play a role in this modulation of activity, helping computationally sparsify sensory information during transmission from layer 4 to layer 5.

Finally, the dense connectivity from interneurons to PCs across dendrites, somata, and the axon initial segments may enable a tight control of the excitability of PCs across all compartments. The function of this inhibition may be to guarantee that excitation is appropriately balanced by inhibition (Vogels and others 2011) not only to prevent runaway excitability but also to produce specific computational goals such as dynamic gain control (Pouille and others 2009), temporal filtering (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001), and gating of information (Vogels and Abbott, 2009), among many possible others (for review, see Isaacson and Scanziani, 2011).

Conclusions and Future Directions

For over a hundred years, a goal in neuroscience has been to decipher the organization of cortical circuits to unveil how they could encode cortical functions. In the past decades, the role of GABAergic interneurons in cortical circuits has become increasingly evident. A first crucial step is to understand how they become integrated into neuronal circuits and recent work has illuminated this issue. In addition to the dense connectivity from interneurons to nearby excitatory neurons, it is now important to include functional information about the synaptic weight of inhibitory connections onto PCs, the synapse dynamics, and how these inhibitory contacts can tightly regulate PC activity in natural behavior. New techniques such as optical activation of genetically targeted cell subtypes make it now possible to record and manipulate the activity of specific cell subtypes and address how they influence cortical network activity and perhaps even specific behaviors. These new tools will likely usher a new era of our understanding of cortical circuits and the role that different subtypes of cells play in these circuits.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This work for supported by the Kavli Institute for Brain Science, the National Eye Institute, the Keck Foundation, and the Marie Curie IOF Program.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Ascoli GA, Alonso-Nanclares L, Anderson SA, Barrionuevo G, Benavides-Piccione R, Burkhalter A, et al. Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:557–68. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Gibson JR, Connors BW. Two dynamically distinct inhibitory networks in layer 4 of the neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2987–3000. doi: 10.1152/jn.00283.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger TK, Perin R, Silberberg G, Markram H. Frequency-dependent disynaptic inhibition in the pyramidal network: a ubiquitous pathway in the developing rat neocortex. J Physiol. 2009;587:5411–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger TK, Silberberg G, Perin R, Markram H. Brief bursts self-inhibit and correlate the pyramidal network. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock DD, Lee WCA, Kerlin AM, Andermann ML, Hood G, Wetzel AW, et al. Network anatomy and in vivo physiology of visual cortical neurons. Nature. 2011;471:177–82. doi: 10.1038/nature09802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Hestrin S. Intracortical circuits of pyramidal neurons reflect their long-range axonal targets. Nature. 2009;457:1133–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Villa KL, Cha JW, So PTC, Kubota Y, Nedivi E. Clustered dynamics of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines in the adult neocortex. Neuron. 2012;74:361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart R, Aronov D, Yuste R. Attractor dynamics of network UP states in the neocortex. Nature. 2003;423:283–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Fairen A. A type of basket cell in superficial layers of the cat visual cortex. A Golgi-electron microscope study. Brain Res. 1982;244:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KAC. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:419–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow EE, Richardson KA, Connors BW. Selective, state-dependent activation of somatostatin-expressing inhibitory interneurons in mouse neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2640–52. doi: 10.1152/jn.90691.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Araya R, Peterka DS, Salierno M, Etchenique R, Yuste R. RuBi-glutamate: two-photon and visible-light photoactivation of neurons and dendritic spines. Front Neural Circuits. 2009 May 27;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.002.2009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Yuste R. Dense inhibitory connectivity in neocortex. Neuron. 2011;69:1188–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Electrical and chemical synapses among parvalbumin fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons in adult mouse neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192159599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Connors BW. Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature. 1999;402:75–9. doi: 10.1038/47035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin S, Galarreta M. Electrical synapses define networks of neocortical GABAergic neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SB, Ko H, Pichler B, Vogelstein J, Ros H, Zeng H, et al. Differential connectivity and response dynamics of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005;14:1045–52. doi: 10.1038/nn.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Ma Y, Agmon A. Submillisecond firing synchrony between different subtypes of cortical interneurons connected chemically but not electrically. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3351–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72:231–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisman N, Silberberg G, Markram H. The neocortical microcircuit as a tabula rasa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407088102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfer C, Glickfeld LL, Atallah BV, Scanziani M. Supra-linear increase of recurrent inhibition during sparse activity in the somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:743–53. doi: 10.1038/nn1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzel D, Zemelman BV, Buetfering C, Wolfel M, Miesenbock G. The columnar and laminar organization of inhibitory connections to neocortical excitatory cells. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:100–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin AM, Andermann ML, Berezovskii VK, Reid RC. Broadly tuned response properties of diverse inhibitory neuron subtypes in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;67:858–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisvárday ZF. GABA in the retina and central visual system. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozloski J, Hamzei-Sichani F, Yuste R. Stereotyped position of local synaptic targets in neocortex. Science. 2001;293:868–72. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5531.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy P, Silberberg G, Lansner A. A cortical attractor network with Martinotti cells driven by facilitating synapses. PloS One. 2012;7:e30752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa KP, Kullmann DM, Woodin MA. Spike-timing dependent plasticity in inhibitory circuits. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letzkus JJ, WolffS BE, Meyer EMM, Tovote P, Courtin J, Herry C, et al. A disinhibitory microcircuit for associative fear learning in the auditory cortex. Nature. 2011;480:331–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Hu H, Agmon A. Short-term plasticity of unitary inhibitory-to-inhibitory synapses depends on the presynaptic interneuron subtype. J Neurosci. 2012;32:983–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5007-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry LM, Packer AM, Fino E, Nikolenko V, Sippy T, Yuste R. Quantitative classification of somatostatin-positive neocortical interneurons identifies three interneuron subtypes. Front Neural Circuits. 2010;4:12. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer HS, Schwarz D, Wimmer VC, Schmitt AC, Kerr JN, Sakmann B, et al. Inhibitory interneurons in a cortical column form hot zones of inhibition in layers 2 and 5A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113648108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB. An organization principle for cerebral function: the unit module and the distributed system. In: Schmitt FO, editor. Mindful brain. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1982. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama M, Pérez-Garci E, Nevian T, Bock T, Senn W, Larkum ME. Dendritic encoding of sensory stimuli controlled by deep cortical interneurons. Nature. 2009;457:1137–41. doi: 10.1038/nature07663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niell CM, Stryker MP. Highly selective receptive fields in mouse visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7520–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0623-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DH, Peron SP, Huber D, Svoboda K. Neural activity in barrel cortex underlying vibrissa-based object localization in mice. Neuron. 2010;67:1048–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T, Kawaguchi Y. Cortical inhibitory cell types differentially form intralaminar and interlaminar subnetworks with excitatory neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10533–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2219-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer AM, McConnell DJ, Fino E, Yuste R. Axodendritic overlap and laminar targeting explain connectivity from interneurons to pyramidal cells in juvenile neocortex. Cerebral Cortex. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs210. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer AM, Yuste R. Dense, unspecific connectivity of neocortical parvalbumin-positive interneurons: a canonical microcircuit for inhibition? J Neurosci. 2011;31:13260–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3131-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F, Marin-Burgin A, Adesnik H, Atallah BV, Scanziani M. Input normalization by global feedforward inhibition expands cortical dynamic range. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1577–85. doi: 10.1038/nn.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F, Scanziani M. Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward inhibition. Science. 2001;293:1159–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y Cajal S. La Textura del Sistema Nerviosa del Hombre y los Vertebrados. Madrid: Moya; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan CA, Schummers J, Van Wart A, Kuhlman SJ, Wilson NR, Huang ZJ, et al. Response features of parvalbumin-expressing interneurons suggest precise roles for subtypes of inhibition in visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;67:847–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg G, Markram H. Disynaptic inhibition between neocortical pyramidal cells mediated by Martinotti cells. Neuron. 2007;53:735–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohya K, Kameyama K, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Tsumoto T. GABAergic neurons are less selective to stimulus orientation than excitatory neurons in layer II/III of visual cortex, as revealed by in vivo functional Ca2+ imaging in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2145–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4641-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Tamas G, Lujan R, Buhl E. Salient features of synaptic organisation in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:113–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanyants A, Hof PR, Chklovskii DB. Geometry and structural plasticity of synaptic connectivity. Neuron. 2002;34:275–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamás G, Buhl EH, Somogyi P. Massive autaptic self-innervation of GABAergic neurons in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6352–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06352.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Hu H, Huang ZJ, Agmon A. Robust but delayed thalamocortical activation of dendritic-targeting inhibitory interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2187–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710628105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Lamy C. Functional maps of neocortical local circuitry. Front Neurosci. 2007;1:19–42. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.002.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels TP, Abbott LF. Gating multiple signals through detailed balance of excitation and inhibition in spiking networks. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:483–91. doi: 10.1038/nn.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels TP, Sprekeler H, Zenke F, Clopath C, Gerstner W. Inhibitory plasticity balances excitation and inhibition in sensory pathways and memory networks. Science. 2011;334:1569–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1211095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Roby KD, Callaway EM. Immunochemical characterization of inhibitory mouse cortical neurons: three chemically distinct classes of inhibitory cells. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:389–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.22229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura Y, Callaway EM. Fine-scale specificity of cortical networks depends on inhibitory cell type and connectivity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1552–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura Y, Dantzker JL, Callaway EM. Excitatory cortical neurons form fine-scale functional networks. Nature. 2005;433:868–73. doi: 10.1038/nature03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]