Abstract

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a common hereditary disorder which is characterized by fluid-filled cysts in the kidney. Mutation in either PKD1, encoding polycystin-1 (PC1), or PKD2, encoding polycystin-2 (PC2), are causative genes of PKD. Recent studies indicate that renal cilia, known as mechanosensors, detecting flow stimulation through renal tubules, have a critical function in maintaining homeostasis of renal epithelial cells. Because most proteins related to PKD are localized to renal cilia or have a function in ciliogenesis. PC1/PC2 heterodimer is localized to the cilia, playing a role in calcium channels. Also, disruptions of ciliary proteins, except for PC1 and PC2, could be involved in the induction of polycystic kidney disease. Based on these findings, various PKD mice models were produced to understand the roles of primary cilia defects in renal cyst formation. In this review, we will describe the general role of cilia in renal epithelial cells, and the relationship between ciliary defects and PKD. We also discuss mouse models of PKD related to ciliary defects based on recent studies. [BMB Reports 2013; 46(2): 73-79]

Keywords: Intraflagellar transport, Polycystic kidney disease, Polycystin-1, Polycystin-2, Primary cilia

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a common genetic disorder and is manifested by defects in renal ithelial cells, resulting in an increase of cell proliferation and cyst formation (1). PKD is a systemic disorder which is characterized by cysts in thekidney, liver and pancreas (2).

ADPKD is caused by mutations of either PKD1 (85%) or PKD2 (15%) genes, which encode polycystin-1 (PC1) or polycystin-2 (PC2) respectively (3). PC1 is a large integral membrane protein, which includes a long N-terminal extracellular domain, a short C-terminal intracellular domain, and eleven transmembrane domains, and acts as a G-protein-coupled receptor (4-6). PC1 is localized to primary cilia, lateral domain of the plasma membrane (7), and regions of cell-matrix interaction (8). The C-terminal, cytoplasmic tail, of PC1 is cleaved to generate products, which interact with transcription factors. PC2 is a membrane protein with six transmembrane domains, and is considered to be a cation channel with specificity for calcium (9,10). This protein is localized to not only primary cilia (11), but also to subcellular compartments, including the plasma membrane (12) and endoplasmic reticulum. PC1 and PC2 interact via their C-terminus (13) to form transmembrane receptor-ion channel complex in the primary cilia of renal epithelial cells (1,14). This protein complex regulates intracellular calcium levels through its channel, which is stimulated by fluid flow in the renal tubule, and affects calcium-related pathways. Recent studies have shown that dysfunctions of PC1 and PC2 result in decreased intracellular calcium in renal epithelial cells of PKD (15). Some aberrant signaling pathways have been identified in PKD. Among these, the signaling pathway related to calcium, cyclic AMP (cAMP) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is well-known as a major signaling in PKD (16-19). In addition to these pathways, dysregulation of cell cycle, JAK-STAT pathway, canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathway are observed in PKD.

Recent studies suggest that defects of primary cilia are also related to the formation of renal cystic kidneys (20,21). The cilium acts as a mechanosensor in kidney tubules, in regulating homeostasis of renal epithelial cells. Many signaling components are localized to the membrane of renal primary cilia. Accumulating results show that proteins related to PKD are localized to the primary cilia, and disruptions of ciliary proteins, including intraflagellar transport (IFT), induce PKD (3). These findings indicate that defects of cilia act as a driving force to induce PKD (22).

Consistent with these recent findings, malfunctions of primary cilia, induced by mutations of ciliary proteins, is correlated with PKD. Therefore, it is important to identify the cyst formation mechanism associated with ciliary malfunctions using in vivo studies, to develop therapeutic targets for PKD. Here, we will focus on recent advances in understanding the ciliary roles in polycystic kidney and PKD mouse models accompanied by cilia defects.

PRIMARY CILIA AND IFT

The cilium is commonly divided into two groups, motile and non-motile cilia. Motile cilia that have a 9+2 microtubule configuration (3) are mainly located on epithelial cells, and promote the movement of substances. On the other hand, non-motile cilia, known as primary cilia, have a 9+0 microtubule arrangement. Primary cilia projected from the cell membrane act as mechanosensor to sense mechanical forces, growth factors and chemical compounds from extracellular environments (23). Primary cilia have important roles for regulating intracellular signaling, such as Hedgehog (Hh), Wnt, platelet- derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) α, and mechanosignaling related to PKD1/2 complex (24).

Regulation of ciliogenesis is critical to maintain functional cilia. The key factor related to ciliogenesis is Intraflagellar Transport (IFT), which is a bi-directional movement multi-protein complex (25). IFT particles are divided into two complexes, A and B. The complex A, known as retrograde transport, moves from ciliary tip to base with dynein, while the complex B, known as anterograde transport, moves from base to ciliary tip with kinesin-2 (26). IFT particles are regarded as vehicles for transporting cargos to regulate cilia assembly, maintenance, and function (27). In addition, these particles have a function in carrying cilia membrane proteins. Consistent with these roles for cilia, cilia defects or mutations of IFT genes are related to human disease, such as PKD, left-right asymmetry defects, cancer, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) (24,28).

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CILIA DEFECTS AND POLYCYSTIC KIDNEY DISEASE

In renal epithelial cells, primary cilia protrude into lumen of the renal tubules to sense fluid flow (29). Polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2) are localized to the membrane of cilium, and form a PC1/PC2 complex as a calcium channel. PC1 acts as mechanosensor to detect the bending of cilium induced by flow stimulation that transmits extracellular signals to PC2, which, in turn, induces Ca2+ influx to cytosol (11, 30), hence this complex and primary cilia in renal cells regulates intracellular signaling associated with calcium concentration such as the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, which are increased in PKD (31). Moreover, various signaling molecules related to Hh, PDGFRα, and calcium signaling are localized to the cilia membrane (32). Therefore, defects of cilia or ciliary proteins are sufficient to induce pathological disorders.

Among various diseases, PKD is one which is related to cilia defects. Many proteins whose functions are disrupted in PKD are localized to cilium membrane or to the ciliary basal body (24,33). Also, disruption of cilia proteins are involved in calcium signaling related to PKD, implicating a relationship between ciliary signaling and cyst formation (34). Consistent with this, the intracellular calcium level is decreased in PKD epithelial cells compared to normal renal epithelial cells (35). Recent studies have demonstrated that malfunction of renal cilia induces intracellular cAMP, leading to an increase of renal cell proliferation through the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, known as a hallmark of cystic kidney (36,37). Therefore, to elucidate the functions of ciliary genes in vivo is important to identify the disease inducing mechanisms and therapeutic targets of PKD.

MOUSE MODELS OF POLYCYSTIC KIDNEY INDUCED BY MUTATIONS OF CILIARY PROTEINS

Kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1

As we described above, PC1 localized to primary cilia is a major causative gene for the development of polycystic kidneys. In the case of complete knockout of Pkd1 in the mouse, a complex embryonic lethality is observed: defects in formation of the kidney, pancreas, heart and capillary blood vessels (38-40). However, Pkd1flox/-:Ksp-Cre mice generated by deletion of exons 2-4 by Ksp-Cre are born, but consistently develop cystic kidneys (14). Consistent with this, components related to the MAPK/ERK pathway, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and cell proliferation, are dramatically increased in the cystic kidney of this mouse (14).

Pkd2ws25/- mice

The WS25 allele is generated by the integration of an exon 1 disrupted by introduction of a neor cassette into intron 1 of Pkd2, without replacement of the wild-type exon 1 (41,42). This mutation causes an unstable allele, which increases the somatic mutation rate of Pkd2 (42,43). The knockout of Pkd2 is embryonically lethal between embryonic day 13.5 and parturition, whereas the Pkd2ws25/- mouse is born (44). The Pkd2ws25/- mouse is an animal model of ADPKD with hepatic cysts and cardiac defects, and exhibits renal failure (44). Studies using this mouse model have shown that renal cilia in the cystic kidney of Pkd2ws25/- mouse have normal phenotype (45), but cilia of cystic cholangiocytes are short and malformed (46).

Oak ridge polycystic kidney mice

The oak ridge polycystic kidney (ORPK) mouse resembles human ARPKD with respect to cystic kidneys and hepatic disease (47,48). This mouse is the first model showing a relationship between polycystic kidney and ciliary malfunction (48,49). The orpk allele was driven by insertion mutation on the intron near the 3’end of the gene, partially disrupting the function and expression of Ift88 (Tg737, polaris) (50). Increased levels of PC2 in primary cilia is observed in the kidneys of ORPK mice (49). The Tg737orpk mutant mice have polycystic kidneys with shortened cilia on renal epithelial cells (47,48). In addition to renal disorder, hepatic and pancreatic defects, skeletal patterning abnormalities and hydrocephalus are observed in the ORPK mouse (51-53).

Deletion of Ift20 in the mouse kidney

Inactivation of Ift20 in the mouse kidney using Cre-loxP system promotes postnatal cystic kidneys lacking cilia (54). The conditional allele of Ift20 was generated by targeting exon 2 and 3 (54). Deletion of Ift20 in kidneys collecting duct cells induces mis-orientation of the mitotic spindle and increases of canonical Wnt signaling, leading to increased renal cell proliferation (54). In addition to this in vivo study, there are some evidences showing that Ift20 is a candidate gene related to PKD. Ift20 is associated with Golgi complex to regulate cilia assembly and is involved in the localization of PC2 to cilia (55).

Mice with a conditional allele for Ift140

Deletion of Ift140, subunit of IFT complex A, in renal collecting duct cells leads to renal cyst formation with disruption of the cilia assembly, but this mutation does not have a function on mitotic spindle orientation (56). Several genes which are hallmarks of polycystic kidney and are associated with the canonical Wnt pathway, Hedgehog, Hippo and fibrosis were significantly increased in Ift140-deleted kidneys (56).

Kif3α-targeted mouse

Constitutive knockout of Kif3α, a subunit of kinesin-II that is critical for ciliogenesis, results in an absence of cilia in the embryonic node, situs inversus, and abnormalities of the neural tube, pericardium and smites (57,58). This constitutive Kif3α knockout mouse shows embryonic lethality before renal organogenesis (59). In contrast, in the case of specific targeting of Kif3α in renal tubular epithelial cells, viable offspring were born and developed cystic kidneys (59). These cystic lining epithelial cells have no cilia due to Kif3α inactivation, and show increased proliferation, apoptosis, expression of β-catenin, c-Myc, and decreased p21cip1 (59).

Congenital polycystic kidney mouse

The Cystin encoded by Cys1 is a 145-amino acid cilium-associated protein (60). The congenital polycystic kidney (cpk) mice have mutations of Cystin localized to the primary cilia (61-64). This mutant develops renal cysts and biliary dysgenesis and is considered as ARPKD (61). The kidneys of cpk/cpk mice have multiple cellular and extracellular abnormalities (63), including increased expression of proto-oncogenes, such as c-myc, c-fos (65,66), elevated expression of growth factors (67), abnormal expression of genes related to cell adhesion (68), and overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (69). The renal cystic epithelial cells of cpk mice have different length and morphology of cilia (70).

Inversin-targeted mice

The Inversin protein localizes to the primary cilia, cell junctions and nucleus, and acts as a regulator of β-catenin activity and canonical Wnt pathway (71). The inversion of embryonic turning (inv) mutation is generated by random insertion of tyrosinase minigene in the OVE210 transgenic line (72,73). This random insertion disrupts Inversin encoded by Invs, which localizes to primary apical cilia (74). Phillips et al. (75) have demonstrated that normal looking monocilia were observed in cystic kidneys of inv/inv mice. However, the inv mutant shows a reversal of left-right asymmetry, and renal cyst known as diseases induced by ciliary defects (76).

Bbs2-deficient mice

The proteins encoded by Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) genes, except for BBS6, are localized to ciliated organisms (77,78). BBS2 is one of the proteins that form the complex BBSome, which is localized to the membrane of the cilium and is required for ciliogenesis. Several evidences suggest that BBS4 and BBS6 are expressed in basal bodies of primary cilia (79,80). The ciliogenic function of the BBS complex is related to the Rab8 GDP/GTP exchange factor, which localizes to basal body and contacts the BBSome (81).

Bbs2-deficient mice are generated by deletion of exons 5-14, and show the phenotype of cystic kidneys (82). Interestingly, renal cilia are observed in Bbs2-deficient mice, but their shape is abnormal compared to cilia of wild-type kidneys (82). In addition to polycystic kidney, this mutant mouse develops retinal degeneration, obesity and olfactory dysfunction (82).

Juvenile cystic kidney mouse

The jck allele has a missense mutation in the NIMA (never in mitosis A)-related kinase 8 encoded by Nek8 (83). NIMA is a serine/threonine kinase in Aspergillus nidulans, and has a function in regulating mitosis (84). Published results suggest that Nek8 is overexpressed in human breast cancers, indicating that Nek8 has a role in cell proliferation (84,85).

In wild-type kidney, Nek8 is found in the proximal region of renal cilia, whereas kidneys of the jck mutant show that Nek8 is localized to the entire length of renal cilia (84). The kidneys of jck mice have cysts in multiple nephron segments like ADPKD, and increased cAMP levels, which promote renal cell proliferation and fluid secretion (86). Also, the lengthened cilia with overexpression of polycystins are observed in kidneys of jck mice (86).

CONCLUSION

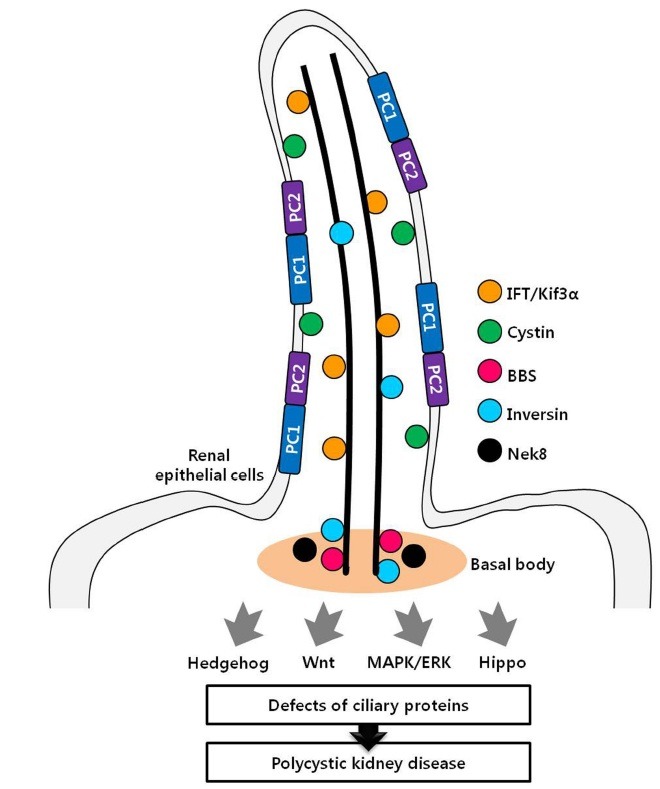

The role of the renal primary cilia is under the spotlight, because the disruption of ciliary structures and proteins is associated with polycystic kidney. To determine the mechanism between defects of renal cilia and polycystic kidneys, various cystic kidney mouse models have been generated. Based on many studies, mutation of some proteins localized to primary cilia, such as IFT, leads to cyst formation accompanied by ciliary defects. This mechanism of cyst formation seems to occur via increased renal cell proliferation. Consistent with this, mutations of some proteins localized to ciliary membrane, such as PC1 and PC2, result in the development of cystic kidneys. However, these ciliary membrane proteins, non-IFT family proteins, which act as receptor and signaling molecules, seem to have no effect on the regulation of ciliogenesis. Instead of functioning in ciliogenesis, these proteins are localized to ciliary membranes to regulate the cilia function as mechanosensors rather than regulating ciliogenesis. Taken together, dysfunctions of proteins associated with renal primary cilia have an effect on cyst formation of the kidneys (Fig. 1). To identify the exact mechanism of cyst formation induced by ciliary defects, further in vivo studies are needed. It is important to reveal the mechanism of cystic kidney development, because a successful treatment for PKD has not yet been developed. Therefore, we expect that these mechanism studies might be used for the selection of novel therapeutic targets of PKD.

Fig. 1. Localization of ciliary proteins related to polycystic kidney. Many proteins localized to renal cilia are associated with PKD. Disruptions of these proteins induce cystic kidneys through various signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

This Research was supported by the Sookmyung Women's University Research Grants 2010.

References

- 1.Fedeles S., Gallagher A. R. Cell polarity and cystic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. (2012) doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2337-z. 2012 Nov 16 [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 23161205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson, P. D., Goilav, B. Cystic disease of the kidney. Ann. Rev. Pathol. 2:341–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauli, S. M., Zhou, J. Polycystins and mechanosensation in renal and nodal cilia. Bioessays. (2004);26:844–856. doi: 10.1002/bies.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nims N., Vassmer D., Maser R. L. Transmembrane domain analysis of polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease-1 (PKD1) gene: evidence for 11 membrane- spanning domains. Biochemistry. (2003);42:13035–13048. doi: 10.1021/bi035074c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X. Phosphorylation, protein kinases and ADPKD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. (2011);1812:1219–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delmas P., Nomura H, Li X., Lakkis M., Luo Y., Segal Y., Fernandez-Fernandez J. M., Harris P., Frischauf A. M., Brown D. A., Zhou J. Constitutive activation of G-proteins by polycystin-1 is antagonized by polycystin-2. J. Biol. Chem. (2002);277:11276–11283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapin H. C., Caplan M. J. The cell biology of polycystic kidney disease. J. Cell Biol. (2010);191:701–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson P. D., Geng L., Li X., Burrow C. R. The PKD1 gene product, "polycystin-1," is a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein that colocalizes with alpha2beta1- integrin in focal clusters in adherent renal epithelia. Lab. Invest. (1999);79:1311–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Bukanov N. Polycystic kidney diseases: from molecular discoveries to targeted therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (2008);65:605–619. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7362-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Perrett S., Kim K., Ibarra C., Damiano A. E., Zotta E., Batelli M., Harris P. C., Reisin I. L., Arnaout M. A., Cantiello H. F. Polycystin-2, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), is a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2001);98:1182–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nauli S. M., Alenghat F. J., Luo Y., Williams E., Vassilev P., Li X., Elia A. E., Lu W., Brown E. M., Quinn S. J., Ingber D. E., Zho J. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat. Genet. (2003);33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanaoka K., Qian F., Boletta A., Bhuni A. K., Pionte K., Tsiokas L., Sukhatme V. P., Guggino W. B., Germino G. G. Co-assembly of polycystin-1 and -2 produces unique cation-permeable currents. Nature. (2000);408:990–994. doi: 10.1038/35050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian F., Germino F. J., Cai Y., Zhang X., Somlo S., Germino G. G. PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nat. Genet. (1997);16:179–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibazaki S., Yu Z., Nishio S., Tian X., Thomson R. B., Mitobe M., Louvi A., Velazquez H., Ishibe S., Cantley L. G., Igarashi P., Somlo S. Cyst formation and activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway after kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1. Hum. Mol. Genet. (2008);17:1505–1516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kip S. N., Hunter L. W., Ren Q., Harris P. C., Somlo S., Torres V. E., Sieck G. C., Qian Q. [Ca2+]i reduction increases cellular proliferation and apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells: relevance to the ADPKD phenotype. Circ. Res. (2005);96:873–880. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163278.68142.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao Y., Kim J., Faubel S., Wu J. C., Falk S. A., Schrier R. W., Edelstein C. L. Caspase inhibition reduces tubular apoptosis and proliferation and slows disease progression in polycystic kidney disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2005);102:6954–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408518102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres V. E., Bankir L., Grantham J. J. A case for water in the treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2009);4:1140–1150. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00790209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang M. Y., Ong A. C. Mechanism-based therapeutics for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: recent progress and future prospects. Nephron. Clin. Pract. (2012);120:25–35. doi: 10.1159/000334166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park E. Y., Woo Y. M., Park J. H. Polycystic kidney disease and therapeutic approaches. BMB Rep. (2011);44:359–368. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.6.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O. Targeting dysregulated cell cycle and apoptosis for polycystic kidney disease therapy. Cell Cycle. (2007);6:776–779. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.7.4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan J., Wang Q., Snell W. J. Cilium-generatedsignaling and cilia-related disorders. Lab. Invest. (2005);85:452–463. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoder B. K., Tousson A., Millican L., Wu J. H., Bugg C. E., Jr.,, Schafer J. A., Balkovetz D. F. Polaris, a protein disrupted in orpk mutant mice, is required for assembly of renal cilium. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. (2002);282:F541–552. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00273.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizuno N., Taschner M., Engel B. D., Lorentzen E. Structural studies of ciliary components. J. Mol. Biol. (2012);422:163–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veland I. R., Awan A., Pedersen L. B., Yoder B. K., Christensen S. T. Primary cilia and signaling pathways in mammalian development, health and disease. Nephron Physiol. (2009);111:39–53. doi: 10.1159/000208212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taschner M., Bhogaraju S., Lorentzen E. Architecture and function of IFT complex proteins in ciliogenesis. Differentiation. (2012);83:S12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa H., Marshall W. F. Ciliogenesis: building the cell's antenna. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. (2011);12:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrm3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y., Park A., Sun Z. Intraflagellar transport proteins are essential for cilia formation and for planar cell polarity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2010);21:1326–1333. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009091001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen L. B., Veland I. R., Schroder J. M., Christensen S. T. Assembly of primary cilia. Dev. Dyn. (2008);237:1993–2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurd T. W., Margolis B. Cystin, cilia, and cysts: unraveling trafficking determinants. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2009);20:2485–2486. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009090996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Praetorius H. A., Spring K. R. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J. Membr. Biol. (2001);184:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi T., Nagao S., Wallace D. P., Belibi F. A., Cowley B. D., Pelling J. C., Grantham J. J. Cyclic AMP activates B-Raf and ERK in cyst epithelial cells from autosomal-dominant polycystic kidneys. Kidney Int. (2003);63:1983–1994. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lancaster M. A., Gleeson J. G. The primary cilium as a cellular signaling center: lessons from disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. (2009);19:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahjoub M. R., Trapp M. L., Quarmby L. M. NIMA-related kinases defective in murine models of polycystic kidney diseases localize to primary cilia and centrosomes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2005);16:3485–3489. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rydholm S., Zwartz G., Kowalewski J. M., Kamali-Zare P., Frisk T., Brismar H. Mechanical properties of primary cilia regulate the response to fluid flow. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. (2010);298:F1096–1102. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00657.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowley B. D., Jr. Calcium, cyclic AMP, and MAP kinases: dysregulation in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. (2008);73:251–253. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi Y. H., Suzuki A., Hajarnis S., Ma Z., Chapin H. C., Caplan M. J., Pontoglio M., Somlo S., Igarashi P. Polycystin-2 and phosphodiesterase 4C are components of a ciliary A-kinase anchoring protein complex that is disrupted in cystic kidney diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2011);108:10679–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016214108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan J., Seeger-Nukpezah T., Golemis E. A. The role of the cilium in normal and abnormal cell cycles: emphasis on renal cystic pathologies. Cell Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1052-z. 2012 Jul 11 [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22782110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulter C., Mulroy S., Webb S., Fleming S., Brindle K., Sandford R. Cardiovascular, skeletal, and renal defects in mice with a targeted disruption of the Pkd1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2001);98:12174–12179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211191098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu W., Peissel B., Babakhanlou H., Pavlova A., Geng L., Fan X., Larson C., Brent G., Zhou J. Perinatal lethality with kidney and pancreas defects in mice with a targetted Pkd1 mutation. Nat. Genet. (1997);17:179–181. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim K., Drummond I., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Klinger K., Arnaout M. A. Polycystin 1 is required for the structural integrity of blood vessels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2000);97:1731–1736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040550097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu G., D'Agati V., Cai Y., Markowitz G., Park J. H., Reynolds D. M., Maeda Y., Le T. C., Hou H., Jr., Kucherlapati R., Edelmann W., Somlo S. Somatic inactivation of Pkd2 results in polycystic kidney disease. Cell. (1998);93:177–188. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X., Harris P. C., Somlo S., Batlle D., Torres V. E. Effect of calcium-sensing receptor activation in models of autosomal recessive or dominant polycystic kidney disease, Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. (2009);24:526–534. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu G., Somlo S. Molecular genetics and mechanism of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. (2000);69:1–15. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu G., Markowitz G. S., Li L., D'Agati V. D., Factor S. M., Geng L., Tibara S., Tuchman J., Cai Y., Park J. H., van Adelsberg J., Hou H., Jr., Kucherlapati R., Edelmann W., Somlo S. Cardiac defects and renal failure in mice with targeted mutations in Pkd2. Nat. Genet. (2000);24:75–78. doi: 10.1038/71724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson R. B., Mentone S., Kim R., Earle K., Delpire E., Somlo S., Aronson P. S. Histopathological analysis of renal cystic epithelia in the Pkd2WS25/- mouse model of ADPKD. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. (2003);285:F870–880. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00153.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stroope A., Radtke B., Huang B., Masyuk T., Torres V., Ritman E., LaRusso N. Hepato-renal pathology in pkd2ws25/- mice, an animal model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Pathol. (2010);176:1282–1291. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moyer J. H., Lee-Tischler M. J., Kwon H. Y., Schrick J. J., Avner E. D., Sweeney W. E., Godfrey V. L., Cacheiro N. L., Wilkinson J. E., Woychik R. P. Candidate gene associated with a mutation causing recessive polycystic kidney disease in mice. Science. (1994);264:1329–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.8191288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pazour G. J., Dickert B. L., Vucica Y., Seeley E. S., Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B., Cole D. G. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J. Cell Biol. (2000);151:709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pazour G. J., San Agustin J. T., Follit J. A., Rosenbaum J. L., Witman G. B. Polycystin-2 localizes to kidney cilia and the ciliary level is elevated in orpk mice with polycystic kidney disease. Curr. Biol. (2002);12:R378–380. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehman J. M., Michaud E. J., Schoeb T. R., Aydin-Son Y., Miller M., Yoder B. K. The Oak Ridge Polycystic Kidney mouse: modeling ciliopathies of mice and men. Dev. Dyn. (2008);237:1960–1971. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Q., Davenport J. R., Croyle M. J., Haycraft C. J., Yoder B. K. Disruption of IFT results in both exocrine and endocrine abnormalities in the pancreas of Tg737(orpk) mutant mice. Lab. Invest. (2005);85:45–64. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banizs B., Pike M. M., Millican C. L., Ferguson W. B., Komlosi P., Sheetz J., Bell P. D., Schwiebert E. M., Yoder B. K. Dysfunctional cilia lead to altered ependyma and choroid plexus function, and result in the formation of hydrocephalus. Development. (2005);132:5329–5339. doi: 10.1242/dev.02153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cano D. A., Murcia N. S., Pazour G. J., Hebrok M. Orpk mouse model of polycystic kidney disease reveals essential role of primary cilia in pancreatic tissue organization. Development. (2004);131:3457–3467. doi: 10.1242/dev.01189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jonassen J. A., San Agustin J., Follit J. A., Pazour G. J. Deletion of IFT20 in the mouse kidney causes misorientation of the mitotic spindle and cystic kidney disease. J. Cell Biol. (2008);183:377–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Follit J. A., Tuft R. A., Fogarty K. E., Pazour G. J. The intraflagellar transport protein IFT20 is associated with the Golgi complex and is required for cilia assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. (2006);17:3781–3792. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jonassen J. A., SanAgustin J., Baker S. P., Pazour G. J. Disruption of IFT complex A causes cystic kidneys without mitotic spindle misorientation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2012);23:641–651. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marszalek J. R., Ruiz-Lozano P., Roberts E., Chien K. R., Goldstein L. S. Situs inversus and embryonic ciliary morphogenesis defects in mouse mutants lacking the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (1999);96:5043–5048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takeda S., Yonekawa Y., Tanaka Y., Okada Y., Nonaka S., Hirokawa N. Left-right asymmetry and kinesin superfamily protein KIF3A: new insights in determination of laterality and mesoderm induction by kif3A-/- mice analysis. J. Cell Biol. (1999);145:825–836. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin F., Hiesberger T., Cordes K., Sinclair A. M., Goldstein L. S., Somlo S., Igarashi P. Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2003);100:5286–5291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836980100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tao B., Bu S., Yang Z., Siroky B., Kappes J. C., Kispert A., Guay-Woodford L. M. Cystin localizes to primary cilia via membrane microdomains and a targeting motif. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2009);20:2570–2580. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoder B. K., Hou X., Guay-Woodford L. M. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2002);13:2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiu M. G., Johnson T. M., Woolf A. S., Dahm-Vicker E. M., Long D. A., Guay-Woodford L., Hillman K. A., Bawumia S., Venner K., Hughes R. C., Poirier F., Winyard P. J. Galectin-3 associates with the primary cilium and modulates cyst growth in congenital polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Pathol. (2006);169:1925–1938. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hou X., Mrug M., Yoder B. K., Lefkowitz E. J., Kremmidiotis G., D'Eustachio P., Beier D. R., Guay-Woodford L. M. Cystin, a novel cilia-associated protein, is disrupted in the cpk mouse model of polycystic kidney disease. J. Clin. Invest. (2002);109:533–540. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Preminger G. M., Koch W. E., Fried F. A., McFarland E., Murphy E. D., Mandell J. Murine congenital polycystic kidney disease: a model for studying development of cystic disease. J. Urol. (1982);127:556–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cowley B. D., Jr., Smardo F. L., Jr., Grantham J. J., Calvet J. P. Elevated c-myc protooncogene expression in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (1987);84:8394–8398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cowley B. D., Jr., Chadwick L. J., Grantham J. J., Calvet J. P. Elevated proto-oncogene expression in polycystic kidneys of the C57BL/6J (cpk) mouse. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (1991);1:1048–1053. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V181048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakamura T., Ebihara I., Nagaoka I., Tomino Y., Nagao S., Takahashi H., Koide H. Growth factor gene expression in kidney of murine polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (1993);3:1378–1386. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V371378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rocco M. V., Neilson E. G., Hoyer J. R., Ziyadeh F. N. Attenuated expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecules in murine polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. (1992);262:F679–686. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.4.F679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rankin C. A., Suzuki K., Itoh Y., Ziemer D. M., Grantham J. J., Calvet J. P., Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPS in cultured C57BL/6J-cpk kidney tubules. Kidney Int. (1996);50:835–844. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winyard P., Jenkins D. Putative roles of cilia in polycystic kidney disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. (2011);1812:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gerdes J. M., Davis E. E., Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. (2009);137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yokoyama T., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Montgomery C. A., Elder F. F., Overbeek P. A. Reversal of left-right asymmetry: a situs inversus mutation. Science. (1993);260:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.8480178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guay-Woodford L. M. Murine models of polycystic kidney disease: molecular and therapeutic insights. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. (2003);285:F1034–1049. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00195.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morgan D., Eley L., Sayer J., Strachan T., Yates L. M., Craighead A. S., Goodship J. A. Expression analyses and interaction with the anaphase promoting complex protein Apc2 suggest a role for inversin in primary cilia and involvement in the cell cycle. Human Mol. Genet. (2002);11:3345–3350. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.26.3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Phillips C. L., Miller K. J., Filson A. J., Nurnberger J., Clendenon J. L., Cook G. W., Dunn K. W., Overbeek P. A., Gattone V. H. 2nd, Bacallao R. L. Renal cysts of inv/inv mice resemble early infantile nephronophthisis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2004);15:1744–1755. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000131520.07008.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sugiyama N., Tsukiyama T., Yamaguchi T. P., Yokoyama T. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is not involved in renal cyst development in the kidneys of inv mutant mice. Kidney Int. (2011);79:957–965. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mykytyn K., Mullins R. F., Andrews M., Chiang A. P., Swiderski R. E., Yang B., Braun T., Casavant T., Stone E. M., Sheffield V. C. Bardet-Biedl syndrome type 4 (BBS4)-null mice implicate Bbs4 in flagella formation but not global cilia assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2004);101:8664–8669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J. B., Gerdes J. M., Haycraft C. J., Fan Y., Teslovich T. M., May-Simera H., Li H., Blacque O. E., Li L., Leitch C. C., Lewis R. A., Green J. S., Parfrey P. S., Leroux M. R., Davidson W. S., Beales P. L., Guay-Woodford L. M., Yoder B. K., Stormo G. D., Katsanis N., Dutcher S. K. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. (2004);117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ansley S. J., Badano J. L., Blacque O. E., Hill J., Hoskins B. E., Leitch C. C., Kim J. C., Ross A. J., Eichers E. R., Teslovich T. M., Mah A. K., Johnsen R. C., Cavender J. C., Lewis R. A., Leroux M. R., Beales P. L., Katsanis N. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature. (2003);425:628–633. doi: 10.1038/nature02030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J. C., Badano J. L., Sibold S., Esmail M. A., Hill J., Hoskins B. E., Leitch C. C., Venner K., Ansley S. J., Ross A. J., Leroux M. R., Katsanis N., Beales P. L. The Bardet-Biedl protein BBS4 targets cargo to the pericentriolar region and is required for microtubule anchoring and cell cycle progression. Nat. Genet. (2004);36:462–470. doi: 10.1038/ng1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nachury M. V., Loktev A. V., Zhang Q., Westlake C. J., Peranen J., Merdes A., Slusarski D. C., Scheller R. H., Bazan J. F., Sheffield V. C., Jackson P. K. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. (2007);129:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nishimura D. Y., Fath M., Mullins R. F., Searby C., Andrews M., Davis R., Andorf J. L., Mykytyn K., Swiderski R. E., Yang B., Carmi R., Stone E. M., Sheffield V. C. Bbs2-null mice have neurosensory deficits, a defect in social dominance, and retinopathy associated with mislocalization of rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (2004);101:16588–16593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405496101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu S., Lu W., Obara T., Kuida S., Lehoczky J., Dewar K., Drummond I. A., Beier D. R. A defect in a novel Nek-family kinase causes cystic kidney disease in the mouse and in zebrafish. Development. (2002);129:5839–5846. doi: 10.1242/dev.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sohara E., Luo Y., Zhang J., Manning D. K., Beier D. R., Zhou J. Nek8 regulates the expression and localization of polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2008);19:469–476. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bowers A. J., Boylan J. F. Nek8, a NIMA family kinase member, is overexpressed in primary human breast tumors. Gene. (2004);328:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith L. A., Bukanov N. O., Husson H., Russo R. J., Barry T. C., Taylor A. L., Beier D. R., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O. Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. (2006);17:2821–2831. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]