Abstract

The PIDDosome, which is an oligomeric signaling complex composed of PIDD, RAIDD and caspase-2, can induce proximity-based dimerization and activation of caspase-2. In the PIDDosome assembly, the adaptor protein RAIDD interacts with PIDD and caspase-2 via CARD:CARD and DD:DD, respectively. To analyze the PIDDosome assembly, we purified all of the DD superfamily members and performed biochemical analyses. The results revealed that caspase-2 CARD is an insoluble protein that can be solubilized by its binding partner, RAIDD CARD, but not by full-length RAIDD; this indicates that full-length RAIDD in closed states cannot interact with caspase-2 CARD. Moreover, we found that caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized and interact with full-length RAIDD in the presence of PIDD DD, indicating that PIDD DD initially binds to RAIDD, after which caspase-2 can be recruited to RAIDD via a CARD:CARD interaction. Our study will be useful in determining the order of assembly of the PIDDosome. [BMB Reports 2013; 46(9): 471-476]

Keywords: Apoptosis, CARD, Caspase-2, DD, PIDD, PIDDosome, RAIDD

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis, which is also known as programmed cell death, is one of the most studied fields in bioscience because of its biological importance (1-4). Failure to control apoptosis is the cause of several human diseases, such as cancer, neurodegenerative disease, and many immune related diseases (1,5-9). Apoptosis proceeds through sequential activations of caspases, which are synthesized as single-chain zymogens and activated by proteolytic cleavage. Proteolytic cleavage is important to maintain the integrity of caspase active sites and therefore required for caspase activation (10,11). Caspases can be divided into 2 classes based on their roles and activation mechanism, initiator caspases, such as caspase-2, -8, -9, -10, and effector caspases such as caspase-3 and -7 (12-16). Initiator caspases are activated by induced dimerization via recruitment to oligomeric signaling complexes. In contrast, effector caspases are activated upon cleavage by activated initiator caspases. The PIDDosome is a well-known oligomeric signaling complex that leads to the activation of caspase-2 (17). Assembly of the PIDDosome can induce proximity-based dimerization and activation of caspase-2. Other known initiator caspases activating complexes include the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), which activates caspase-8 (18), the apoptosome for caspase-9 activation (19), and the inflammasome, which leads to caspase-1 activation (20-23). Despite the important role of caspase activating complexes in activation of initiator caspases, their assembly mechanisms have not been well characterized (4).

Although the function and classification of caspase-2 is still unclear, many studies have shown that caspase-2 is an initiator caspase that plays an important role in genotoxic stress induced apoptosis by acting upstream of the mitochondria (24,25). For caspase-2 activation, the PIDDosome must be formed. The PIDDosome is composed of three proteins, p53-induced protein with a death domain (PIDD), RIP-associated Ich-1/Ced-3 homologous protein with a death domain (RAIDD) and caspase-2 (4,17,26). PIDD contains 910 residues with 7 leucine rich repeats (LRRs), 2 ZU-5 domains and a C-terminal death domain (DD). PIDD can be cleaved into shorter fragments generating a PIDD-N fragment of 48 kD (residues 1-446), a PIDD-C fragment of 51 kD (residues 447-910) and a PIDD-CC fragment of 37 kD (residues 589-910). Auto-cleavage of PIDD determines the downstream signaling events. The PIDD-C fragment mediates activation of NFκB via the recruitment of RIP1 and NEMO, while PIDD-CC causes caspase-2 activation, which leads to apoptosis (27). RAIDD is an adaptor protein that contains both an N-terminal caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and a C-terminal DD (28-30). Caspase-2 possesses an N-terminal CARD pro-domain (31-34). Both CARD and DD with the death effector domain (DED) and the Pyrin domain (PYD) belong to the DD superfamily, which is a well-known protein interaction module (4,22,35). Many DD superfamilies contain proteins that participate in the formation of large molecular machines involved in activation of signaling enzymes, such as caspases and kinases. For the PIDDosome assembly, RAIDD and PIDD interact with each other via their DDs, while RAIDD and caspase-2 interact with each other via their CARDs (30,31,36,37).

Previous structural and biochemical studies have shown that the core of the PIDDosome was composed of 5 PIDD DD and 7 RAIDD DD molecules with unique angles and the PIDDosome containing three protein components was successfully reconstituted in vitro (26,38). To further analyze the PIDDosome assembly, we purified all DD superfamily members that are critical to assembly of the PIDDosome. Although obtaining functional DD superfamily members has been difficult owing to insolubility of the DD superfamily under physiological conditions, we purified successfully all functional DD superfamily members, including caspase-2 CARD and RAIDD CARD, as well as the full-length RAIDD, RAIDD DD, and PIDD DD (39,40). Our biochemical experiments revealed that caspase-2 CARD is an insoluble protein that can be solubilized by its binding partner, RAIDD CARD, but not by full-length RAIDD, indicating that full-length RAIDD in a closed state cannot interact with caspase-2 CARD. RAIDD has been reported to exist in both an opened and closed form, and it is not surprising that closed RAIDD cannot accommodate caspase-2 CARD. In addition, we found that caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized and can interact with full-length RAIDD in the presence of PIDD DD, indicating that PIDD DD initially binds to RAIDD, after which caspase-2 is recruited to RAIDD via CARD:CARD interaction. The results of the present study will be useful in determination of the order of assembly of the PIDDosome.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Purification of DD superfamily members involved in assembly of the PIDDosome

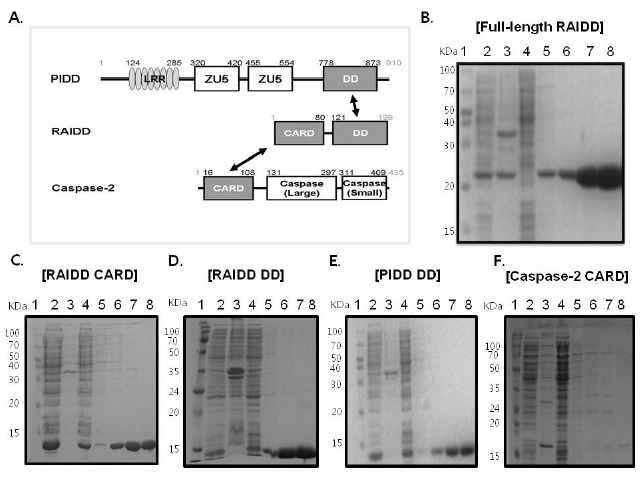

The PIDDosome is a caspase-2 activating complex composed of 3 proteins: PIDD, RAIDD, and caspase-2. Caspase-2 is recruited by this complex, after which it is activated by a proximity induced self-cleavage mechanism. Complex formation is a critical step involved in the activation of caspase-2. The PIDDosome is assembled via a CARD:CARD interaction between RAIDD and caspase-2 and a DD:DD interaction between RAIDD and PIDD (Fig. 1A). Although recent studies have revealed important biochemical features of the PIDDosome, its assembly mechanism is still unclear.

Fig. 1. Purification of PIDDosome components for in vitro analysis. (A) Domain organizations of PIDDosome components, PIDD, RAIDD, and caspase-2. RAIDD interacts with PIDD via a DD:DD interaction (black arrow) and with caspase-2 via a CARD:CARD interaction (black arrow). LRR, Leucine-Rich Repeats; ZU5, Zo-1 and UNC-5 protein containing domain; DD, Death Domain; CARD, Caspase Recruiting Domain. (B) His-tag affinity purification of full-length RAIDD. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lane 5, washing; Lanes 6-8, imidazole eluted fraction. (C) His-tag affinity purification of RAIDD CARD. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lane 5, washing; Lanes 6-8, imidazole eluted fraction. (D) His-tag affinity purification of RAIDD DD. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lane 5, washing; Lanes 6-8, imidazole eluted fraction. (E) His-tag affinity purification of PIDD DD. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lane 5, washing; Lanes 6-8, imidazole eluted fraction. (F) His-tag affinity purification of caspase-2 CARD. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lane 5, washing; Lanes 6-8: imidazole eluted fraction.

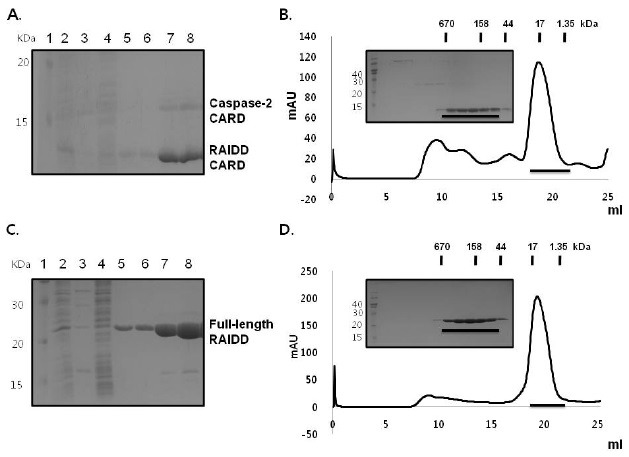

To further understand the assembly mechanism involved in formation of the PIDDosome, especially the order of complex formation, we attempted to purify all of the DD superfamily members in the PIDDosome and generate stable complexes of them in vitro. Unlike other DD superfamilies that are soluble after overexpression in bacteria (Fig. 1B-E), caspase-2 CARD is insoluble when it is over-expressed (Fig. 1F). To overcome the insolubility of caspase-2 CARD and obtain the RAIDD and caspase-2 complex, we co-expressed RAIDD CARD with its binding partner, caspase-2 CARD, which did not contain any tag. As shown in Fig. 2A, caspase-2 was co-expressed, solubilized, and co-migrated with RAIDD CARD on SDS-PAGE. However, co-eluted caspase-2 CARD was soon aggregated and dissociated from RAIDD CARD. The gel-filtration profile showed that caspase-2 CARD was missing during the gel-filtration chromatography step (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, we concluded that caspase-2 CARD is an unstable member of the DD superfamily that is solubilized by its binding partner, RAIDD CARD. Although caspase-2 CARD can bind to RAIDD CARD in vitro, the binding is not complete and caspase-2 CARD remains unstable.

Fig. 2. Caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized by its binding partner, RAIDD CARD, but not by full-length RAIDD. (A) His-tag pull-down assay of caspase-2 CARD with RAIDD CARD. RAIDD CARD with His-tag and caspase-2 CARD without His-tag were co-expressed. Co-eluted caspase-2 CARD is shown. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lanes 5 and 6, washing; Lanes 7-8, imidazole eluted fraction. (B) Fractions from a pull-down assay containing RAIDD CARD and co-eluted caspase-2 CARD were subjected to gel filtration chromatography. The peak fractions (black bar) were loaded onto SDS-PAGE. (C) His-tag pull-down assay for caspase-2 CARD with full-length RAIDD. Full-length RAIDD with His-tag and caspase-2 CARD without His-tag were co-expressed. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lanes 5 and 6, washing; Lanes 7-8, imidazole eluted fractions. (D) Fractions from pull-down assay containing full-length RAIDD and co-eluted caspase-1 CARD were subjected to gel filtration chromatography. The peak fractions (black bar) were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized by its binding partner, RAIDD CARD, but not by full-length RAIDD

To analyze the interaction and solubilization of caspase-2 by RAIDD, we conducted a pull-down assay with full-length RAIDD. RAIDD is a dynamic adaptor protein with a structure and solubility that is changed by pH and temperature (38); therefore, we did not expect full-length RAIDD to interact with caspase-2 CARD, even though separately purified RAIDD CARD and RAIDD DD can interact with caspase-2 CARD and PIDD DD, respectively. As expected, caspase-2 CARD without His-tag was not co-eluted with His-tagged full-length RAIDD when subjected to a His-tag pull-down assay followed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2C, 2D). The gel-filtration profile confirmed that caspase-2 CARD was not solubilized by and did not interact with co-expressed full-length RAIDD. Taken together, the results of this study and previous studies demonstrate that intact RAIDD can interact with PIDD DD, but not caspase-2 CARD, despite interaction of the separated domains of RAIDD, RAIDD CARD, and RAIDD DD with caspase-2 CARD and PIDD DD.

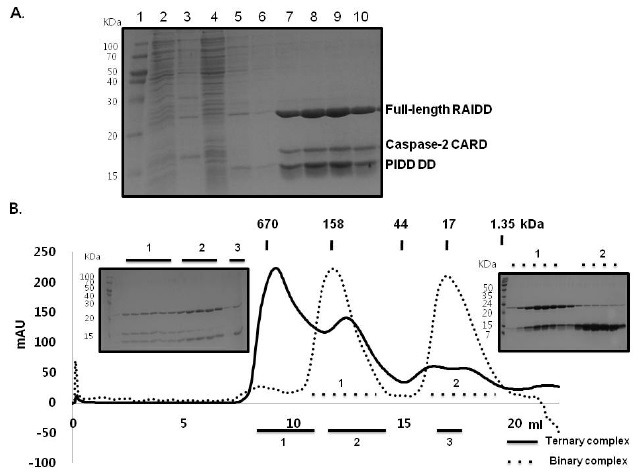

Caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized and interact with full-length RAIDD in the presence of PIDD DD

Full-length adaptor proteins that contain two death domain superfamily members such as RAIDD and FADD have often been reported to fail to interact with their binding partner in intact form (41). These adapter proteins have evolved many regulatory elements to avoid accidental induction of cell death, including conformational changes. Because full-length RAIDD did not interact with caspase-2 CARD, but did interact with PIDD DD, we investigated whether full-length RAIDD could interact with caspase-2 in the presence of PIDD DD. To accomplish this, we performed a His-tag pull-down assay using samples containing co-expressed RAIDD with His-tag, PIDD DD with His-tag and caspase-2 CARD without His-tag. During analysis, all 3 proteins were detected upon SDS-PAGE, indicating that caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized and interact with full-length RAIDD in the presence of PIDD DD (Fig. 3A). When the buffer condition of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0) and 150 mM NaCl was used for gel filtration chromatography, a complex peak centered at approximately 9.5 mL in a Superdex 200 column was obtained (Fig. 3B). Because the individual components would have elution peaks at around 16-18 mL and the complex containing RAIDD and PIDD DD would have elution peaks at around 12 ml, the much larger molecular complex containing all three proteins should correspond to the ternary complex of PIDD DD: RAIDD: caspase-2 CARD. The SDS-PAGE loaded with the peak fractions obtained from the ternary complex confirmed that it contains 3 proteins, RAIDD, PIDD DD, and caspase-2 CARD (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Caspase-2 CARD can be solubilized and interacts with full-length RAIDD in the presence of PIDD DD. (A) His-tag pull-down assay for caspase-2 CARD with full-length RAIDD and PIDD DD. Full-length RAIDD with His-tag, PIDD DD with His-tag, and caspase-2 CARD without His-tag were co-expressed. The position of each protein including co-eluted caspase-2 CARD on SDS-PAGE is shown. Lane 1, marker; Lane 2, supernatant of the cell lysate; Lane 3, pellet of the cell lysate; Lane 4, flow through after incubation with Ni-NTA beads; Lanes 5 and 6, washing; Lanes 7-10, imidazole eluted fractions. (B) Fractions from pull-down assay containing full-length RAIDD, PIDD DD and co-eluted caspase-2 CARD were subjected to gel filtration chromatography. Peaks numbered 1-3 (black bar) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The ternary complex indicates a sample containing full-length RAIDD with His-tag, PIDD DD with His-tag, and caspase-2 CARD without His-tag. Binary complex indicates sample containing fulllength RAIDD and PIDD DD.

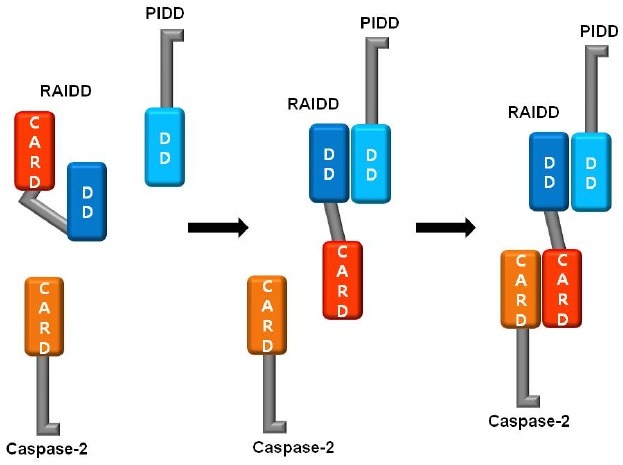

Model of the mechanism of PIDDosome assembly

Finally, we proposed a model of the process of PIDDosome assembly. RAIDD may exist in equilibrium between the open and the closed states. Under normal conditions, the closed form of RAIDD might be dominant. It has been suggested that the existence of closed forms of adaptor molecules for apoptosis, such as FADD and RAIDD is responsible for fine control of important cellular process (38,42). Upon genotoxic stress, RAIDD favors the open conformation and binds to PIDD first via a DD:DD interaction to allow PIDDosome formation. Interaction of PIDD with RAIDD via DDs can stabilize the open conformation of RAIDD, after which caspase-2 can be recruited to the complex via a CARD:CARD interaction (Fig. 4). The results of the present study will be useful for elucidation of the order of PIDDosome assembly.

Fig. 4. Model of the process for PIDDosome formation. RAIDD may exist in an equilibrium between the open and closed states. Upon the genotoxic stress, RAIDD favors the open conformation and binds to PIDD first via DD:DD interaction to allow PIDDosome formation. Interaction of PIDD to RAIDD stabilizes the open conformation of RAIDD, enabling caspase-2 to be recruited to the complex via CARD:CARD interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

Previously reported clones for the expression of RAIDD (amino acid residue 1-199), RAIDD DD (amino acid residue 94-199), RAIDD CARD (amino acid residue 1-92), and PIDD DD (amino acid residue 777-883) were used (38). The cDNA of mouse caspase-2 was used as a template for PCR and cloned into pOKD plasmid vector that was made in house to add or remove the His-tag. The caspase-2 CARD contains amino acids residues 18 to 164.

Recombinant full-length RAIDD, RAIDD CARD, RAIDD DD, and PIDD DD were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) RILP and purified as previously described (38). Caspase-2 CARD was expressed in the BL21 (DE3) E. coli line. The purification process for all target proteins was similar to the process used for RAIDD DD and PIDD DD purification (43). Briefly, expression was induced by treatment with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) overnight at 20℃. Then, the bacteria were collected, resuspended and lysed by sonication in 80 mL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 5 mM β-ME). Next, the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 rpm for 1 h at 4℃. The His-tagged target was purified subsequently by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen) and then subjected to gel-filtration chromatography using S-200 (GE healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl.

Pull-down assay

A coexpression system was used to conduct a pull-down assay. RAIDD and RAIDD CARD in pET 26b vector were co-transformed with caspase-2 CARD in pOKD vector separately into BL21(DE3) E. coli competent cells. Expression was then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG overnight at 20℃. The cells were subsequently collected and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), after which the lysate was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant fractions were applied to a gravity-flow column (Bio-Rad) packed with Ni-NTA affinity beads (Qiagen). The unbound bacterial proteins were removed from the column using washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 60 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol). For the ternary complex test, PIDD DD expressed cells were mixed with RAIDD:caspase-2 CARD co-expressed cells and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer. Complex formation was detected by SDS-PAGE.

Complex assay with gel-filtration chromatography

For gel filtration analysis to detect complex formation, protein samples from a pull-down assay were applied to a gel-filtration column (Superdex 200 HR 10/30, GE healthcare) that had been pre-equilibrated with a solution of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl. Then, the fractions were collected and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The same method was used to detect ternary complex formation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2012-010870).

References

- 1.Navratil J. S., Ahearn J. M. Apoptosis, clearance mechanisms, and the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. (2001);3:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11926-001-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raff M. C., Barres B. A., Burne J. F., Coles H. S., Ishizaki Y., Jacobson M. D. Programmed cell death and the control of cell survival. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. (1994);345:265–268. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobson M. D., Weil M., Raff M. C. Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell. (1997);88:347–354. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park H. H., Lo Y. C., Lin S. C., Wang L., Yang J. K., Wu H. The death domain superfamily in intracellular signaling of apoptosis and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. (2007);25:561–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher D. E. Pathways of apoptosis and the modulation of cell death in cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. (2001);15:931–956. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70258-6. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson C. B. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. (1995);267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damiano J. S., Reed J. C. CARD proteins as therapeutic targets in cancer. Curr. Drug. Targets. (2004);5:367–374. doi: 10.2174/1389450043345470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Graaf A. O., de Witte T., Jansen J. H. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: new therapeutic targets in hematological cancer? Leukemia. (2004);18:1751–1759. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoist C., Mathis D. Cell death mediators in autoimmune diabetes - no shortage of suspects. Cell. (1997);89:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boatright K. M., Salvesen G. S. Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. (2003);15:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pop C., Salvesen G. S. Human caspases: Activation, specificity and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. (2009);284:21777–21781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800084200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey N. L., Kumar S. The role of caspases in apoptosis. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. (1998);62:107–128. doi: 10.1007/BFb0102307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denault J. B., Salvesen G. S. Caspases: keys in the ignition of cell death. Chem. Rev. (2002);102:4489–4500. doi: 10.1021/cr010183n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavrik I. N., Golks A., Krammer P. H. Caspases: pharmacological manipulation of cell death. J. Clin. Invest. (2005);115:2665–2672. doi: 10.1172/JCI26252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvesen G. S. Caspases and apoptosis. Essays Biochem. (2002);38:9–19. doi: 10.1042/bse0380009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park H. H. Structural features of caspase-activating complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. (2012);13:4807–4818. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinel A., Tschopp J. The PIDDosome, a protein complex implicated in activation of caspase-2 in response to genotoxic stress. Science. (2004);304:843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.1095432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wajant H. The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science. (2002);296:1635–1636. doi: 10.1126/science.1071553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou H., Henzel W. J., Liu X., Lutschg A., Wang X. Apaf-1, a human protein homologous to C. elegans CED-4, participates in cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase-3. Cell. (1997);90:405–413. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu. Rev. Immunol. (2009);27:229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinon F., Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases: linking an intracellular innate immune system to autoinflammatory diseases. Cell. (2004);117:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park H. H. PYRIN domains and their interactions in the apoptosis and inflammation signaling pathway. Apoptosis. (2012);17:1247–1257. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0775-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae J. Y., Park H. H. Crystal structure of NALP3 protein pyrin domain (PYD) and its implications in inflammasome assembly. J Biol Chem. (2011);286:39528–39536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassus P., Opitz-Araya X., Lazebnik Y. Requirement for caspase-2 in stress-induced apoptosis before mitochondrial permeabilization. Science. (2002);297:1352–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1074721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin S., Lee Y., Kim W., Ko H., Choi H., Kim K. Caspase-2 primes cancer cells for TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by processing procaspase-8. EMBO J. (2005);24:3532–3542. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park H. H., Logette E., Raunser S., Cuenin S., Walz T., Tschopp J., Wu H. Death domain assembly mechanism revealed by crystal structure of the oligomeric PIDDosome core complex. Cell. (2007);128:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinel A., Janssens S., Lippens S., Cuenin S., Logette E., Jaccard B., Quadroni M., Tschopp J. Autoproteolysis of PIDD marks the bifurcation between pro-death caspase-2 and pro-survival NF-kappaB pathway. EMBO J. (2007);26:197–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan H., Dixit V. M. RAIDD is a new 'death' adaptor molecule. Nature. (1997);385:86–89. doi: 10.1038/385086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park H. H., Wu H. Crystal structure of RAIDD death domain implicates potential mechanism of PIDDosome assembly. J. Mol. Biol. (2006);357:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H. H., Wu H. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic studies of the oligomeric death-domain complex between PIDD and RAIDD. Acta. Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. (2007);63:229–232. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107007889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baptiste-Okoh N., Barsotti A. M., Prives C. A role for caspase 2 and PIDD in the process of p53-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. (2008);105:1937–1942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711800105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssens S., Tinel A., Lippens S., Tschopp J. PIDD mediates NF-kappaB activation in response to DNA damage. Cell. (2005);123:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y., Ma W., Benchimol S. Pidd, a new death-domain-containing protein, is induced by p53 and promotes apoptosis. Nat. Genet. (2000);26:122–127. doi: 10.1038/79102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z. H., Mabb A., Miyamoto S. PIDD: a switch hitter. Cell. (2005);123:980–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed J. C., Doctor K. S., Godzik A. The domains of apoptosis: a genomics perspective. Sci. STKE. (2004);2004:re9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2392004re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou J. J., Matsuo H., Duan H., Wagner G. Solution structure of the RAIDD CARD and model for CARD/CARD interaction in caspase-2 and caspase-9 recruitment. Cell. (1998);94:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park H. H. Structural analyses of death domains and their interactions. Apoptosis. (2011);16:209–220. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang T. H., Zheng C., Wu H., Jeon J. H., Park H. H. In vitro reconstitution of the interactions in the PIDDosome. Apoptosis. (2010);15:1444–1452. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0544-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang T. H., Park H. H. Generalized semi-refolding methods for purification of the functional death domain superfamily. J. Biotechnol. (2011);151:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eberstadt M., Huang B., Chen Z., Meadows R. P., Ng S.-C., Zheng L., Lenardo M. J., Fesik S. W. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the FADD (Mort1) death-effector domain. Nature. (1998);392:941–945. doi: 10.1038/31972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott F. L., Stec B., Pop C., Dobaczewska M. K., Lee J. J., Monosov E., Robinson H., Salvesen G. S., Schwarzenbacher R., Riedl S. J. The Fas-FADD death domain complex structure unravels signalling by receptor clustering. Nature. (2009);457:1019–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature07606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee E. W., Seo J., Jeong M., Lee S., Song J. The roles of FADD in extrinsic apoptosis and necroptosis. BMB Rep. (2012);35:496–508. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.9.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang T. H., Bae J. Y., Park O. K., Kim J. H., Cho K. H., Jeon J. H., Park H. H. Identification and analysis of dominant negative mutants of RAIDD and PIDD. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. (2010);1804:1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]