Abstract

Members of the colony stimulating factor cytokine family play important roles in macrophage activation and recruitment to inflammatory lesions. Among them, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is known to be associated with immune response to mycobacterial infection. However, the mechanism through which Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) affects the expression of GM-CSF is poorly understood. Using PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells, we found that MTB infection increased GM-CSF mRNA expression in a dosedependent manner. Induction of GM-CSF mRNA expression peaked 6 h after infection, declining gradually thereafter and returning to its basal levels at 72 h. Secretion of GM-CSF protein was also elevated by MTB infection. The increase in mRNA expression and protein secretion of GM-CSF caused by MTB was inhibited in cells treated with inhibitors of p38 MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK-1), and PI3-K. These results suggest that up-regulation of GM-CSF by MTB is mediated via the PI3-K/MEK1/p38 MAPK-associated signaling pathway. [BMB Reports 2013; 46(4): 213-218]

Keywords: GM-CSF, MEK1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, PI3-K, p38 MAPK

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), remains a major health problem. A third of the world’s population is infected with MTB, which causes approximately 2 million deaths each year (1). This problem is aggravated by the increased appearance of multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB strains (2). Therefore, it is paramount to understand the mechanisms involved in immunity to TB in order to discover novel treatments and vaccines against TB.

Infection of MTB affects the recruitment and activation of circulating effector leukocytes by influencing the induction and secretion of cytokines from infected macrophages (3-5). Infected macrophages release a variety of inflammatory cytokines as defense mechanisms against MTB (6-8). In addition, it has been reported down-regulation of cytokine receptors in T cells resulted in ineffective control of persisting pathogens such as MTB (9). Among these cytokines the granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) plays an important role in the differentiation of monocytes, alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) (10-12). It has been previously reported that GM-CSF can induce the up-regulation of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, such as CD80 and CD86 on antigen presenting cell (APC), and increase their phagocytic activity and stimulatory capacity (13-16). Particularly in the lungs, GM-CSF is very important for macrophage maturation, differentiation, and induction of the TH1 response and host defense (17,18). In GM-CSF deficient mice, the lung architecture is altered and alveolar macrophages become foamy in appearance. In addition, the macrophages are deficient in phagocytic activity and lose Toll-like receptor expression (19). In TB, GM-CSF may also contribute to the cytokine/chemokine milieu responsible for granuloma formation in the lung (17). Over-expression of GM-CSF in the lungs impairs protective immunity against MTB, and careful regulation of pulmonary GM-CSF levels may, therefore, be critical in sustaining protection against chronic tuberculosis disease (18). It was previously reported that GM-CSF regulates both pulmonary surfactant homeostasis and the differentiation and proliferation of functionally competent alveolar macrophages (18,20). However, to date, the role of mycobacterial infection in GM-CSF expression in macrophages are unclear. In this study, we aimed to elucidate whether MTB influences GM-CSF expression in macrophages, and to identify associated signal transduction pathways.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Infection with MTB influences mRNA expression of GM-CSF

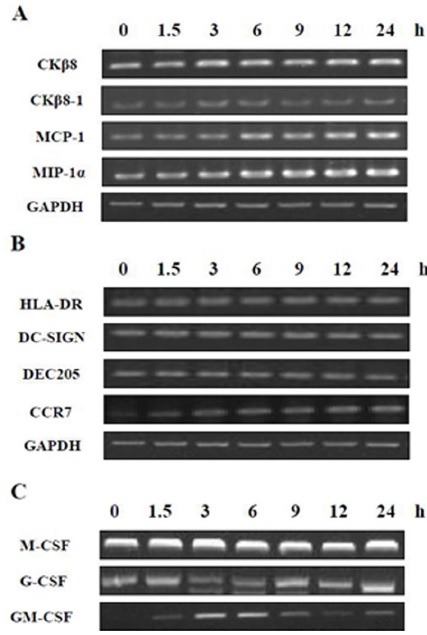

Chemokines are the key molecules that recruit immune cells by chemotaxis and act in leukocyte activation during inflammatory diseases (21). These chemokines help in the formation of granulomas which are critical for the immune responses to MTB (22). In our previous study, we reported that the expression of leukotactin-1, a member of the CC-chemokine family, was up-regulated during MTB infection (23,24). Thus, we first examined whether MTB stimulates the induction of several chemokines, including CKβ8, CKβ8-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1α). CKβ8/CCL23 is a recently identified CC-chemokine, and alternative splicing of the CKβ8 gene produces two different mRNAs that encode CKβ8 and its isoform CKβ8-1 (25,26). We found that the mRNA expression of both chemokines was unchanged by MTB infection (Fig. 1A). Additionally, we found that mRNA expression of MCP-1 and MIP-1α gradually increased after MTB infection in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), and these results were in accordance with those of previous reports (22,27).

Fig. 1. mRNA expression of GM-CSF was affected by MTB. THP-1 cells were treated with PMA (100 nM) for 48 h and were incubated in the presence of MTB for the indicated times (0, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24 h). cDNA were prepared from total RNA of infected cells, and was subjected to PCR to amplify (A) chemokines (CKβ8, CKβ8-1, MCP-1, MIP-1α), (B) DC markers (HLA-DR, DC-SIGN, DEC205, CCR7), and (C) colony stimulating factors (M-CSF, G-CSF, GM-CSF). The PCR products were resolved by 1.8% agarose gel. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

It has been reported that alveolar macrophages of MTB-infected mice have the ability to resemble DCs by up-regulating CD11b, C-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and DEC205 markers depending on the cytokine environment (28,29). Thus, we determined whether MTB stimulated the induction of the DC markers MHC class II (human leukocyte antigen DR; HLA-DR), dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), DEC205 and CCR7 (Fig. 1B). CCR7 is a chemokine receptor which is essential in the transport of DCs to lymph nodes, and which participates in the development of an adaptive immune response to MTB (30). We found that of the chemokines examined, only CCR7 mRNA gradually increased by MTB infection in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

In addition, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), monocyte colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and GM-CSF also play important roles in macrophage recruitment and activation (30,31). G-CSF stimulates the survival, proliferation, differentiation and function of neutrophilic precursor (32,33). M-CSF and GM-CSF are known to be factors of the lungs which are essential in the differentiation of myeloid cells and the immune response (34,35). We determined whether MTB infection influenced mRNA expression of G-CSF, M-CSF, and GM-CSF in PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells by using RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1C, GM-CSF mRNA expression was sharply affected in response to MTB infection. In contrast, we observed no changes in the mRNA expression of G-CSF and M-CSF.

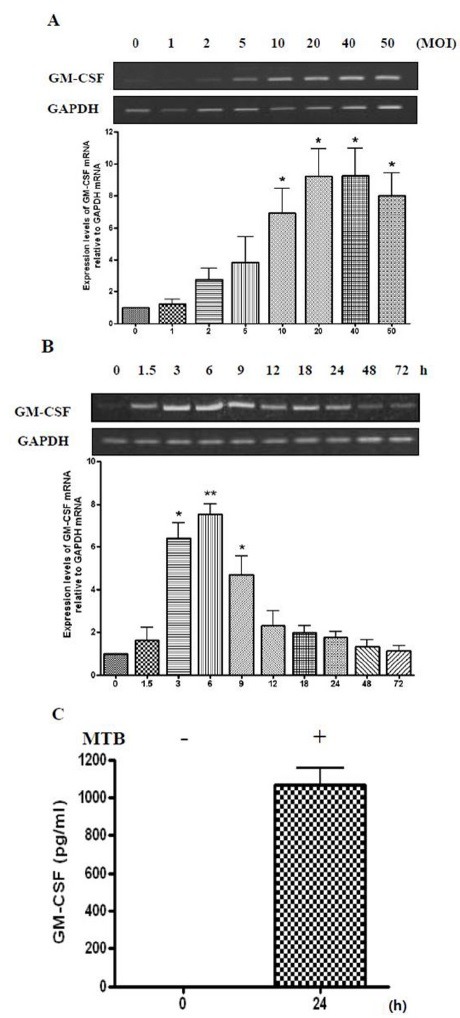

MTB infection increased expression and secretion of GM-CSF

We determined whether the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of MTB influenced the mRNA expression of GM-CSF in differentiated THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were treated with PMA for 48 h and were incubated with MTB for 6 h, and GM-CSF mRNA levels were detected by RT-PCR. GM-CSF expression was up-regulated by MTB infection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A) approaching saturation at 20 MOI. We also examined the effects of MTB infection on the timing of GM-CSF expression. In Fig. 1, we determined the effect of MTB infection in mRNA expression of GM-CSF up to 24 h after infection. We examined whether MTB infection influenced the expression of GM-CSF from 24 h post-infection up to 72 h post-infection in differentiated THP-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, GM-CSF expression increased, peaking at 6 h, and then declined beginning at 9 h post-infection, eventually returning to its basal level by 72 h (Fig. 2B). It is possible that at the early stage of infection, affected macrophages release GM-CSF for the recruitment and activation of leukocytes to remove MTB, while MTB may cause the concurrent suppression of GM-CSF expression to promote its own survival and chronic infection. We determined whether MTB infection induced GM-CSF secretion by culturing PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells for 24 h with or without MTB, and analyzing the culture media by ELISA (Fig. 2C). GM-CSF was not detected in the uninfected control THP-1 cells but significant amounts of GM-CSF (∼1,000 pg/ml) were detected from MTB-infected cells. This result demonstrated that macrophages release copious amounts of GM-CSF in response to MTB infection. This may cause increased recruitment of immune effector cells to the site of the infected macrophage for MTB clearance.

Fig. 2. MTB induces the increased expression and secretion of GM-CSF. (A) Differentiated THP-1 cells were infected with the indicated concentrations (0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40 or 50 MOI) of MTB for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted and cDNA was prepared. PCR analysis was performed using GM-CSF-specific primers. The PCR products were resolved by 1.8% agarose gel (upper panel), to detect GM-CSF. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Densitometric analysis was performed (lower panel). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, and are presented as the expression levels of GM-CSF mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA (The expression level of GM-CSF relative to GAPDH in the absence of mycobacterial infection was set to 1.0). The data represent results from three independent experiments (*P < 0.05 relative to uninfected control). (B) THP-1 cells were differentiated for 48 h and were incubated in the presence of MTB for the indicated times (0, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 48 or 72 h). Next, semi-quantitative RT-PCR was carried out, as above. Densitometric analysis was performed (lower panel). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, and are presented as the expression levels of GM-CSF mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA. (The level of GM-CSF relative to GAPDH without infection by MTB was set to 1.0). The data represent results from five independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 relative to uninfected control). (C) Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of MTB for 24 h, and secretion of GM-CSF was measured by ELISA using cell culture supernatants. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments and are presented as pg/ml.

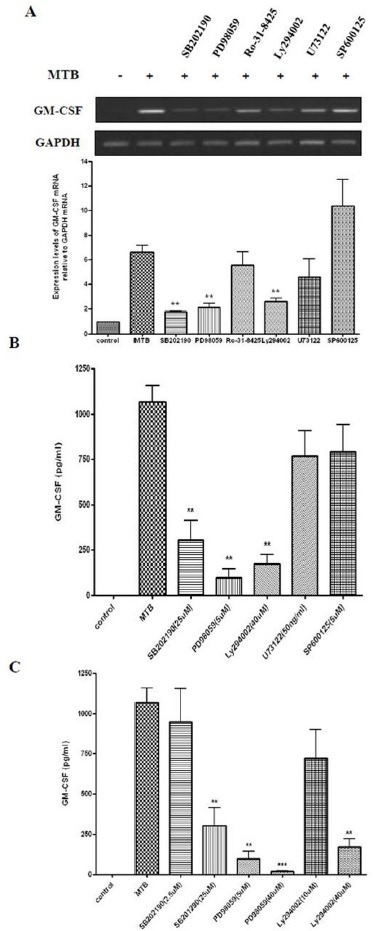

Induction of GM-CSF by MTB is mediated by the PI3-K/MEK1/p38 MAPK

To elucidate the mechanism by which MTB infection affects the expression of GM-CSF, we determined the signaling pathway(s) associated with the MTB-stimulated induction of GM-CSF. THP-1 cells were pre-incubated with inhibitors of specific signaling molecules for 45 min and were then infected with MTB for 4 h. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment with Ro-31-8425 (inhibitor of classic PKC), SP600125 (inhibitor of JNK), or U73122 (an inhibitor of PLC) did not influence GM-CSF induction. In contrast, pre-incubation with SB202190 (inhibitor of p38 MAPK), PD98059 (inhibitorofMEK1), and Ly294002 (inhibitor of PI3-K) dramatically abolished the induction of GM-CSF expression to MTB infection. We further examined whether inhibitor treatment affected GM-CSF secretion. Differentiated THP-1 cells were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of SB202190, PD98059, Ly294002, U73122, and SP600125 for 45 min, followed by MTB infection (10 MOI). Supernatants were harvested 24 h after infection and secreted GM-CSF was measured by ELISA. GM-CSF secretion was also blocked significantly by pre-incubation with SB202190, PD98059, and Ly294002. However, pre-treatment SP600125 or U73122 showed little effect (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we confirmed that the secretion of GM-CSF by MTB infected cells is also significantly blocked by pre-incubation with p38 MAPK inhibitor, MEK1 inhibitor, or PI3-K inhibitor in an inhibitor dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that MTB infection enhances the expression of GM-CSF via activation of p38 MAPK, MEK1, and PI3-K. Further studies are warranted to determine the sequence of these signaling molecules associated with MTB-induced GM-CSF expression.

Fig. 3. MTB-induced expression of GM-CSF is mediated by PI3-K, MEK1, and p38 MAPK. (A) PMA-treated THP-1 cells were pre-incubated with the inhibitors SB202190 (20 μM), PD98059 (50 μM), Ro-31-8425 (50 nM), Ly294002 (10 μM), U73122 (50 ng/ml), SP600125 (10 μM) for 45 min, followed by mycobacterial infection (10 MOI) for 4 h. cDNA was prepared from total RNA extracted from treated cells. PCR analysis was performed using GM-CSF-specific primers. PCR products were analyzed by 1.8% agarose gel (upper panel) to detect GM-CSF expression. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Densitometric analysis was performed (lower panel). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and are presented as the expression levels of GM-CSF mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA (The level of GM-CSF relative to GAPDH in the absence of mycobacterial infection was set to 1.0). Data are the results from three independent experiments (**P < 0.01 relative to MTB infection alone). (B) Differentiated THP-1 cells were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of SB202190, PD98059, Ly294002, U73122 or SP600125 for 45 min, followed by MTB infection (10 MOI). Supernatants were harvested 24 h after infection and secretion of GM-CSF was measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate (**P < 0.01 relative to MTB alone). (C) Differentiated THP-1 cells were treated for 45 min with the indicated concentration of SB202190, PD98059 or Ly294002. Subsequently, MTB was added at 10 MOI. Supernatants were harvested after 24 h, and the protein contents of GM-CSF in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicate (**P < 0.01 or ***P < 0.001 relative to MTB alone).

GM-CSF is known to be an effective immune regulatory molecule, which can stimulate the proliferation, differentiation and maturation of granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages (10, 14). In this study, we demonstrated that; 1) MTB infection induced expression and secretion of GM-CSF, and 2) MTB induced up-regulation of GM-CSF is mediated via the PI3-K/MEK1/p38 MAPK signal pathways. This raises the possibility that these signal transduction pathways may be used as targets for the screening and development of therapeutics of mycobacterial diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inhibitors

Specific inhibitors of p38 MAPK (SB202190), MEK1 (PD98059), classical PKC (Ro-31-8425), JNK (SP600125) and PI3-K (Ly-294002) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). A specific inhibitor of phospholipase C (U73122) was purchased from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of mycobacteria

MTB H37Rv (ATCC27294) used in this study was grown for ∼4 wk at 37℃ as surface pellicles on Sauton medium enriched with 0.4% sodium glutamate and 3.0% glycerol. The surface pellicles were collected and were disrupted by gentle vortexing with 6-mm glass beads. After the clumps had settled, the upper suspension was collected and aliquots were stored at −80℃. Before infection, aliquots were thawed and were quantified for viable colony-forming units (CFU) on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA).

Cell culture and infection with MTB

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 2 mM glutamine, 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37℃ under 5% CO2. THP-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and were treated with 100 nM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; Sigma) for 48 h in order to induce differentiation into macrophage-like cells, which were then washed three times with antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium. Before infection, differentiated THP-1 cells were reconstituted in antibiotic free RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated with MTB H37Rv at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40 or 50 for 6 h. For time-dependent experiments, cells were infected with 10 MOI of MTB H37Rv for 0, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 48 or 72 h. PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 45 min before stimulation with MTB H37Rv for 4 h at a MOI of 10.

RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)

After removing non-phagocytosed bacilli, total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen,Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription with 2 μg total RNA, 0.25 μg of random hexamers (Invitrogen) and 200 U Murine Molony Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (MMLVRT; Invitrogen) for 50 min at 37℃ and for 15 min at 70℃. Subsequent PCR amplification using 0.2 U Taq polymerase (Cosmo Genetech, Seoul, Korea) was performed in a thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) for 25-40 cycles (94℃ for 30s, 55℃-60℃ for 30s, 72℃ for 30s) using the primers listed in supplemental Table 1. PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.8% (w/v) agarose gels containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, and the sizes of the products were determined by comparison to a 100-bp DNA ladder marker (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The intensity of each band amplified by RT-PCR was analyzed using Gel Doc EQ Quantity One (version 4.5, Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) and was normalized to GAPDH mRNA in the corresponding samples.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cell culture supernatants from MTB-infected THP-1 cells were collected 24 h after infection. Cell culture supernatants were analyzed using Duoset antibody pairs for detection of human GM-CSF (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer. GM-CSF concentrations in the samples were calculated using standard curves generated from recombinant GM-CSF, and the results were expressed in pg/ml.

Statistics

Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Further analysis was performed using a Student’s t-test, where P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate significance (GraphPad Prism 4 Software, SanDiego, CA, USA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Korean Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A010381).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO report 2007: Global tuberculosis control; surveillance, planning, financing. WHO; Geneva: 2007. pp. 1–277. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO report 2007: Global MDR-TB and XDR-TB response plan 2007-2008. WHO; Geneva: 2007. pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenton M. J. Macrophages and tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. (1998);5:72–78. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper A. M., Khader S. A. The role of cytokines in the initiation, expansion, and control of cellular immuniy to tuberculosis. Immunol. Rev. (2008);226:191–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters W., Ernst J. D. Mechanisms of cell recruitment in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. (2003);5:151–158. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law K., Weiden M., Harkin T., Tchou-Wong K., Chi C., Rom W. N. Increased release of interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha by bronchoalveolar cells lavaged from involved sites in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. (1996);153:799–804. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majumder N., Bhattacharjee S., Bhattacharyya (Majumdar) S., Dey R., Guha P., Pal N. K., Majumdar S. Restoration of impaired free radical generation and proinflammatory cytokines by MCP-1 in mycobacterial pathogenesis. Scand. J. Immunol. (2008);67:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrara G., Bleck B., Richeldi L., Reibman J., Fabbri L. M., Rom W. N., Condos R. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces CCL18 expression in human macrophages. Scand. J. Immunol. (2008);68:668–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin H. T., Jeong Y. H., Park H. J., Ha S. J. Mechanism of T cell exhaustion in a chronic environment. BMB Rep. (2011);44:271–233. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.4.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burger J. A., Baird S. M., Powell H. C., Sharma S., Eling D. J., Kipps T. J. Local and systemic effects after adenoviral transfer of the murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene into mice. Br. J. Haematol. (2000);108:641–652. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feetwood A. J., Cook A. D., Hamilton J. A. Functions of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Crit. Rev. Immunol. (2005);25:405–428. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v25.i5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daro E., Butz E., Smith J., Teepe M., Maliszewski C. R., McKenna H. J. Comparison of the functional properties of murine dendritc cells generated in vivo with Flt3 ligand, GM-CSF and Flt3 ligand plus GM-CSF. Cytokine. (2002);17:119–130. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan S., Shi C., Han W., Ling R., Li N., Wang T. Effective anti-tumor responses induced by recombinant bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccines based on different tandem repeats of MUC1 and GM-CSF. Eur. J. Cancer. Prev. (2009);18:416–423. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832c3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller G., Pillarisetty V. G., Shah A. B., Lahrs S., Xing Z., Dematteo R. P. Endogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor overexpression in vivo results in the long-term recruitment of a distinct dendritic cell population with enhanced immunostimulatory function. J. Immunol. (2002);169:2875–2885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibata Y., Berclaz P. Y., Chroneos Z. C., Yoshida M., Whitsett J. A., Trapnell B. C. GM-CSF regulates alveolar macrophage differentiation and innate immunity in the lung through PU.1. Immunity. (2001);15:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y., Liu C. H., Roberts A. I., Das J., Xu G., Ren G., Zhang Y., Zhang L., Yuan Z. R., Tan H. S., Das G., Devadas S. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and T-cell responses: what we do and don’t know. Cell Res. (2006);16:126–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin H. S., Lokeshwar B. L., Hsu S. Both granulocyte-macrophage CSF and macrophage CSF control the proliferation and survival of the same subset of alveolar macrophage. J. Immunol. (1989);142:515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Juarrero M., Hattle J. M., Izzo A., Junqueira-Kipnis A. P., Shim T. S., Trapnell B. C., Copper A. M. Disruption of granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor production in the lungs severely affects the ability of mice to control Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. (2005);77:914–922. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ordway D., Henao-Tamayo M., Orme I. M., Gonzalez-Juarrero M. Foamy macrophages within lung granulomas of mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis express molecules characteristic of dendritic cells and antiapototic markers of the TNF receptor-associated factor family. J. Immunol. (2005);175:3873–3881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata Y., Berclaz P. Y., Chroneos Z. C., Yoshida M., Whitsett J. A., Trapnell B. C. GM-CSF regulates alveolar macrophage differentiation and innate immunity in the lung through PU.1. Immunity. (2001);15:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshie O., Imai T., Nomiyama H. Chemokines in immunity. Adv. Immunol. (2001);78:57–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)78002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saukkonen J. J., Bazydlo B., Thomas M., Strieter R. M., Keane J., Kornfeld H. Beta-chemokines are induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and inhibit its growth. Infect. Immun. (2002);70:1684–1693. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1684-1693.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho J. E., Kim Y. S., Park S., Cho S. N., Lee H. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced expression of Leukotactin-1 is mediated by the PI3-K/PDK1/Akt signaling pathway. Mol. Cells. (2010);29:35–39. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho J. E., Park S., Cho S. N., Lee H., Kim Y. S. c-Jun N-terminal (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) are involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced expression of Leukotactin-1. BMB Rep. (2012);45:583–588. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.10.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elagoz A., Henderson D., Babu P. S., Salter S., Grahames C., Bowers L., Roy M. O., Laplante P., Grazzini E., Ahmad S., Lembo P. M. A truncated form of CKbeta8-1 is a potent agonist for human formyl peptide-receptor-like 1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. (2004);141:37–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Youn B. S., Zhang S. M., Broxmeyer H. E., Cooper S., Antol K., Fraser M. Jr., Kwon B. S. Characterization of CKbeta8 and CKbeta8-1: two alternatively spliced forms of human beta-chemokine, chemoattractants for neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes, and potent agonists at CC chemokine receptor 1. Blood. (1998);91:3118–3126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim Y., Gong J., Zhang M., Xue W., Barnes P. F. Production on monocyte chemoattractant Protein 1 in Tuberculosis Patients. Infect. Immun. (1998);66:2319–2322. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2319-2322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ordway D., Harton M., Henao-Tamayo M., Montoya R., Orme I. M., Gonzalez-Juarrero M. Enhanced macrophage activity in granulomatous lesions of immune mice challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. (2006);176:4931–4939. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soilleux E. J., Morris L. S., Leslie G., Chehimi J., Luo Q., Levroney E., Trowsdale J., Montaner L. J., Doms R. W., Weissman D., Coleman N., Lee B. Constitutive and induced expression of DC-SIGN on dendritic cell and macrophage subpopulation in situ and in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. (2002);71:445–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf A. J., Linas B., Trevejo-Nunez G. J., Kincaid E., Tamura T., Takatsu K., Ernst J. D. Mycobacterim tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J. Immunol. (2007);179:2509–2519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.North R. J., Jung Y. J. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. (2004);22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roilides E., Walsh T. J., Pizzo P. A., Rubin M. Granulocyte-stimulating factor enhances the phagocytic and bactericidal activity of normal and defective human neutrophil. J. Infect. Dis. (1991);163:579–583. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung H. K., Kim S. W., Byun S. J., Ko E. M., Chung H. J., Woo J. S., Yoo J. G., Lee H. C., Yang B. C., Kwon M., Park S. B., Park J. K., Kim K. W. Enhanced biological effects of Phe140Asn, a novel human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mutant, on HL60 cells. BMB Rep. (2011);44:686–691. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.10.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin H. S., Lokeshwar B. L., Hsu S. Both granulocyte-macrophage CSF and macrophage CSF control the proliferation and survival of the same subset of alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol. (1989);142:515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins D. M., Sanchez-Campillo J., Rosas-Taraco A. G., Higgins J. R., Lee E. J., Orme I. M., Gonzalez-Juarrero M. Relative levels of M-CSF and GM-CSF influence the specific generation of macrophage populations during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. (2008);180:4892–4900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]