Abstract

Atherosclerosis, which manifests as acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and peripheral arterial diseases, is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall. Prunella vulgaris, a perennial herb with a worldwide distribution, has been used as a traditional medicine in inflammatory disease. Here, we investigated the effects of P. vulgaris ethanol extract on TNF-α-induced inflammatory responses in human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs). We found that P. vulgaris ethanol extract inhibited adhesion of monocyte/macrophage-like THP-1 cells to activated HASMCs. It also decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, E-selectin and ROS, No production in TNF-α-induced HASMCs and reduced NF-kB activation. Furthermore, P. vulgaris extract suppressed TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). These results demonstrate that P. vulgaris possesses antiinflammatory properties and can regulate TNF-α-induced expression of adhesion molecules by inhibiting the p38 MAPK/ ERK signaling pathway. [BMB Reports 2013; 46(7): 352-357]

Keywords: Adhesion molecules, Atherosclerosis, Human aortic smooth muscle cells, Inflammation, Prunella vulgaris

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of inflammatory disease in the wall of arteries. The recruitment and migration of inflammatory cells from the circulation is mediated by adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecular-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecular-1 (VCAM-1) (1, 2). Substantial advances in basic and experimental science have illuminated the role of inflammation and the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms that contribute to atherogenesis (3, 4). These studies further suggest that risk stratification and therapeutic targeting may help in preventing clinical decline in atherosclerosis.

Human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs) play a major role in lesion development and progression in atherosclerosis (1,2,5,6). The induction of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in smooth muscle cells in response to stimulation by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is crucial to the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerosis (7-13).

A number of herbal medicine-based prescriptions are available for treating atherosclerosis, but their therapeutic efficacies and mechanisms are unclear (14). Ethanol extracts of Prunella vulgaris, a widely distributed perennial herb, have been reported to have diverse health benefits, including prevention of oxidative stress, thrombosis, lipid peroxidation, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and hyperlipidemia (15-17). In vivo studies have provided evidence that P. vulgaris prevents the anti-hyperglycemic effects of exogenous insulin without stimulating insulin secretion (18). However, no report has described the anti-inflammatory effects of P. vulgaris in HASMCs.

In this study, we evaluated the effects of a P. vulgaris ethanol extract on TNF-α-induced adhesion molecule expression in HASMCs and investigated the mechanisms underlying its anti-inflammatory effects. Our results provide a scientific basis for supporting the traditional use of P. vulgaris in atherosclerosis therapy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of P. vulgaris on cytotoxicity and monocyte adhesion in HASMCs

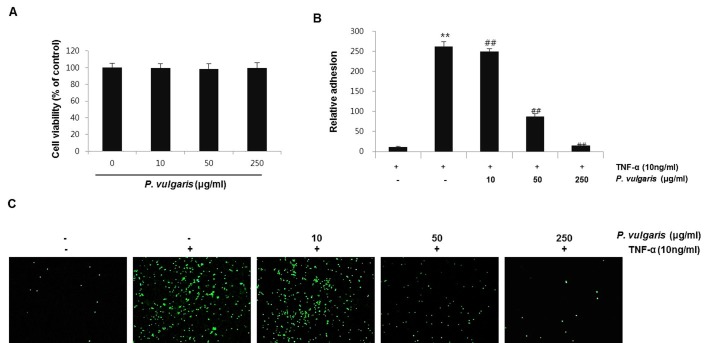

P. vulgaris has been used traditionally as a medical resource in cancer therapy, as well as a diuretic and a treatment for hypertension and inflammation (15). Nevertheless, scientific evidence of P. vulgaris actions is incomplete. In the present study, we investigated the protective effects of a P. vulgaris ethanol extract against vascular inflammation in TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs. First, the cytotoxic effects of P. vulgaris on HASMCs were assessed using the Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 cell viability assay. Treatment of HASMCs for 24 h in the presence or absence of P. vulgaris ethanol extract did not affect cell viability and was not cytotoxic at concentrations in subsequent experiments (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. P. vulgaris ethanol extract protects HASMCs on cell viability and THP-1 cell adhesion. (A) HASMCs were pre-incubated with or without P. vulgaris extract (10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 reagent. β-actin was used as an internal control. (B) Cells were pretreated for 2 h with the indicated concentrations of P. vulgaris extract and washed twice with medium and incubated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. Calcein AM-labeled THP-1 cells or human peripheral blood monocytes were added to the HASMCs and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Adhesion was measured as described in the Materials and Methods. Densitometric analysis of fluorescence, indicating the degree of monocyte adhesion. (C) THP-1 cell adherence to HASMCs was observed under a fluorescence microscope at 100× magnification. Results are expressed as means ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01, vs. control group (Con); ##P < 0.01, vs. TNF-α-only treatment group.

Several studies have reported that TNF-α induces increased adherence of monocytes to HASMCs (19-21). Monocyte adhesion to smooth muscle cells in the arterial wall is considered crucial for the development of vascular diseases (19,22). Therefore, we evaluated the effect of P. vulgaris on monocyte adherence to TNF-α-activated HASMCs using THP-1 adhesion assays. HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg /ml) for 2 h before TNF-α stimulation (10 ng/ml). TNF-α significantly increased adhesion of THP-1 monocytic cells to HASMCs, an effect that was suppressed in a concentration-dependent manner by P. vulgaris extract (Fig. 1B, C). These results suggest that P. vulgaris may protect against vascular inflammation by suppressing adherence of monocytes/macrophages to HASMCs.

Effect of P. vulgaris on cell adhesion molecules and NF-κB activation in TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs

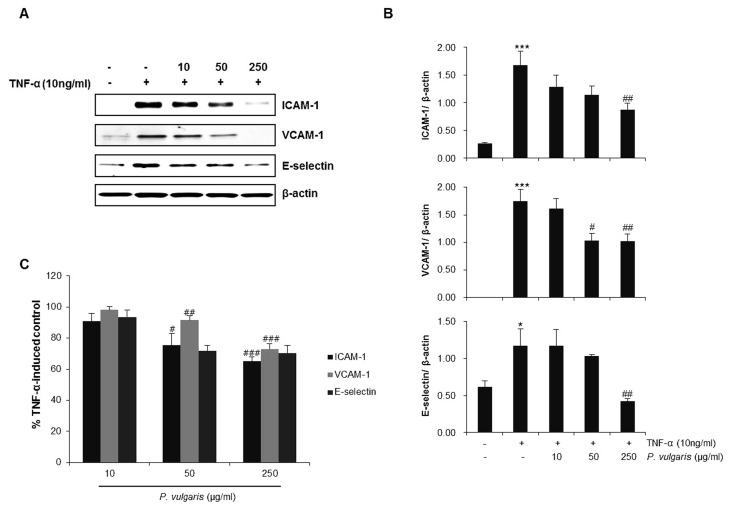

To investigate the anti-inflammatory effect of P. vulgaris on HASMCs, we first examined the expression levels of the adhesion molecules, VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin, by western blotting and cell surface enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Western blot analysis showed that VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin expression induced by TNF-α (10 ng/ml) was significantly reduced by P. vulgaris extract (Fig. 2A, B). ELISA results also demonstrated that P. vulgaris reduced adhesion molecule expression on the cell surface of TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. P. vulgaris extract reduces the expression of adhesion molecules in TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs. HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h and stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. (A) Expression levels of ICAM-1 and E-selectin were determined by western blot analysis. (B) Densitometric analysis of western blots showing relative levels of adhesion molecule proteins normalized to those of β-actin, used as an internal control. (C) Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005 vs. control group (Con); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.005 vs. TNF-α-only treatment group.

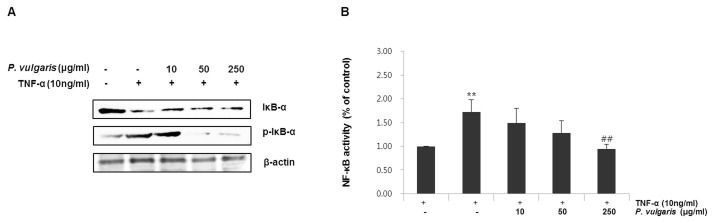

Transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) is wellknown to play an important role in regulating inflammatory reactions and in the development of atherosclerosis (8). It has also been reported to be involved in the activation of VCAM and GATA proteins. Ordinarily, NF κB remains sequestered in the cytoplasm, bound to an inhibitory protein subunit, IκB. Activation leads to the release and degradation of the inhibitory IκB subunit from the heterotrimeric complex and the subsequent translocation of the dimer (p65/p50) into the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of its downstream target genes (23). Thus, we examined the degradation and phosphorylation of IκB-α by western blotting. As can be seen in Fig. 3A, P. vulgaris extract dosedependently prevented the phosphorylation of IκB-α. Furthermore, NF-κB transcription activity was attenuated markedly by P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) in a concentration- dependent manner (Fig. 3B), suggesting that P. vulgaris inhibits TNF-α-induced IκB-α degradation and NF-κB activation.

Fig. 3. Effect of P. vulgaris extract on TNF-α induced IκB-α and NF-κB activation in HASMCs. (A) HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h and stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. Phosphorylation of IκB-α was assessed by Western blotting. (B) Cells were transiently transfected with pGL4.32-NF-κB and a renilla luciferase control reporter vector, and incubated with or without P. vulgaris extract (10, 50, and 250 μg/ml), followed by incubation with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 24 h. NF-κB transcriptional activity was determined using luciferase reporter assays. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. **P < 0.01, vs. control group (Con); ##P < 0.01, vs. TNF-α-only treatment group.

P. vulgaris suppressed TNF-α induced ROS and NO, MAP Kinase in HASMCs

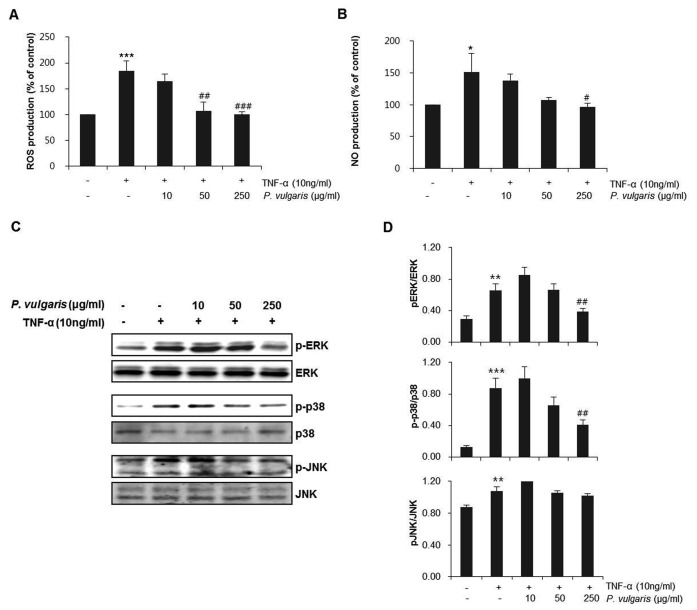

We next investigated the inhibitory effects of P. vulgaris extract on ROS and NO production in TNF-α-induced HASMCs. As can be seen in Fig. 4A, B, ROS and NO production was suppressed by P. vulgaris extract. These results suggest that suppression of intracellular ROS production could be only partially translated into inhibition of NF-κB activation and its downstream adhesion molecule expression in TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs. These findings suggest that smooth muscle cell dysfunction may occur through ROS activation (23,24). In addition, adhesion molecule expression has shown to occur with stimulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, through the induction of ROS (25). Furthermore, ROS activates various transcription factors in vascular cells and may function as a signal in various pathways leading to NF-κB and MAPK activation (24,26-28). To investigate the signaling pathways involved, we tested the effects of P. vulgaris extract on the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Cells were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h, washed with medium and incubated with fresh growth medium containing TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. As shown in Fig. 4, P. vulgaris did not modulate the expression of JNK, but significantly decreased the levels of phosphorylated p38 and ERK, suggesting that protection against TNF-α-induced inflammation by P. vulgaris is mediated by the suppression of p38 and ERK activation (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 4. P. vulgaris extract selectively inhibits production of NO and ROS activation of p38 and ERK MAPKs in TNF-α-stimulated HASMCs. HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h and stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h (A) NO levels were measured as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) The level of ROS was measured as described with a microplate fluorescence reader (C) Expression and phosphorylation of ERK, p38, and JNK MAPKs were assessed by western blotting. (D) Densitometric analysis of western blots showing the relative amounts of phosphorylated and total ERK, p38, and JNK. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 vs. control group (Con); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.005 vs. TNF-α-only treatment group.

P. vulgaris is a medical plant; its components include ursolic acid, oleanolic acid, rutin, hyperoside, cis- and trans-caffeic acid, vitamins, carotenoids, tannin, and organic acids (15). Ursolic acid, among those, is a triterpenoid compound widely distributed in foods, medicinal herbs, and other plants. There is a reported quantitative analysis by GC after derivatization under mild silylating conditions; it showed 0.31% ursolic acid in 20 P. vulgaris samples from southern regions of Korea (28). Ursolic acid has favorable effect in the migration and proliferation of VSMCs (29). In vivo, ursolic acid has long been recognized to possess anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperlipidemic properties in animals (30,31), and P. vulgaris alone has been shown to attenuate inflammatory cytokine expression and apoptosis in pancreatic beta cell-like INS-1 cells (32). We expect there to be ursolic acid in the P. vulgaris extract, and this compounds at least partially explains its activity against vascular inflammation. Further studies are needed to identify the active component(s) of P. vulgaris extract that are responsible for the inhibitory effects on p38 and ERK observed in this study.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that P. vulgaris significantly decreases the transcriptional activity of NF-kB, reduces the adherence of monocytes, and down-regulates adhesion molecule expression in HASMCs by inhibiting p38 and ERK activation. These results indicate that P. vulgaris exerts a protective action against vascular inflammation via a p38- and ERK-dependent mechanism. These results, together with previous evidence for the beneficial anti-thrombotic, anti-hypercholesterolemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of P. vulgaris, strongly point to the potential use of this herbal medicine to prevent the development of atherosclerosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HASMCs were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratory (San Diego, CA, USA). The cells were cultured as monolayers in smooth muscle cell medium (ScienCell) containing essential and nonessential amino acids, vitamins, organic and inorganic compounds, hormones, growth factors, trace minerals, and 2% fetal bovine serum at 37℃ in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells from passages 2 to 6 were used in this study. THP-1 cells (ATCC), a human myelomonocytic cell line widely used to study monocyte/macrophage biology in culture systems (33), were used in cell adhesion assays with HASMCs. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 10% fetal bovine serum.

Preparation and characterization of P. vulgaris extract

P. vulgaris was purchased from Omniherb Co. (Yeongcheon, Korea) and was authenticated based on its microscopic and macroscopic characteristics by the Classification and Identification Committee of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM), Daejeon, Korea. A voucher specimen has been deposited at the herbarium of the Basic Herbal Medicine Research Group at KIOM. Dried P. vulgaris (200 g) was extracted twice with 70% ethanol (with a 2-h reflux). The extract was concentrated under reduced pressure at 40℃ with a rotary evaporator. The decoction was filtered, lyophilized, and stored at 4℃ until use. The lyophilized powder was dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter to make the stock solution. The yield of the dried extract from the starting crude material was 12.01%.

Cell viability

Cells were seeded in 96-well, flat-bottom plates (2 × 104 cells/well) and incubated in the presence of different concentrations of P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 24 h. CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Benchmark Plus microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Promoter assay

NF-κB activity was measured using luciferase reporter assays. HASMCs in 12-well plates were co-transfected with renilla luciferase and pGL4.32-NF-κB, a vector containing an NF-κB response element fused to a firefly luciferase gene, using FuGENE HD reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Twenty- four hours post-transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α and different concentration P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50 and 250 μg/ml). Luciferase activity was assayed 24 h later using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

THP-1 adhesion assay

The adhesion of THP-1 cells to HASMCs was measured as described elsewhere (34). Briefly, HASMCs were grown in 96-well plates and pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37℃. The cells were washed with medium and incubated with fresh growth medium containing TNF-α (10 ng/ml). After 8 h, the medium was removed from the wells, and calcein AM-labeled THP-1 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) in 0.2 ml medium were added to each well. After 1 h incubation at 37℃ in 5% CO2, the microwells were washed twice with 0.2 ml warm medium, and the number of adherent cells was detected by microscopy.

Cell surface ELISA

The surface expression of adhesion molecules on HASMCs was quantified by ELISA (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The cells were seeded in 96-well, flat-bottom plates (2 × 104 cells/well), grown to confluence, and pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37℃. The cells were washed with medium and incubated for 8 h with fresh growth medium containing TNF-α (10 ng/ml). After incubation, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and fixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde for 30 min at 4℃. Bovine serum albumin (1.0% in PBS) was added to the cells to reduce nonspecific binding. The cells were incubated overnight at 4℃ with primary monoclonal antibodies against ICAM-1 or E-selectin (0.25 g/ml, diluted in blocking buffer). The next day, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1 μg/ml, diluted in PBS). The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with the peroxidase substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (1 mg/ml in 0.1 M glycine buffer [pH 10.4], containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM ZnCl2). Absorbance was measured at 405 nm using an EnVision 2103 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). The absorbance values of the isotype-matched control antibody were taken as the blank and subtracted from the experimental values.

Nitric oxide production assay

Nitric oxide production was evaluated by nitrite measurement using the Griess reagent (Sigma, USA). Briefly, an aliquot of cell culture medium was added to an equal volume of Griess reagent and the absorbance measured at 540 nm. Nitrite concentrations were determined using sodium nitrite as a standard.

Intracellular ROS production assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well, flat-bottom plates (2 × 104 cells/well) were pre-treated with various concentrations of P. vulgaris extract for 2 h, followed by addition of TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. The cells were stained for 15 min at 37℃ with 5 μm DCFG-DA. The fluorescence intensity was measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emissions using a microplate fluorescence reader.

Western blot analysis

The expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, ERK, phospho-ERK, JNK, phospho-JNK, p38 and phospho-p38, IkB-α (Cell signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) was determined by western blot analysis. HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) for 2 h and washed with medium and incubated with fresh growth medium containing TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 8 h. After treatment, the cells were washed twice in PBS and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% [v/v] NP-40, 0.1% [w/v] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 1 h. The lysates were collected after centrifuging at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4℃. HASMCs were pretreated with P. vulgaris extract (0, 10, 50, and 250 μg/ml) as described above and stimulated with TNF-α for 4 h. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Protein lysates (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels, electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA), and probed with the appropriate antibodies. The blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham). In all immunoblotting experiments, blots were reprobed with an antibody against β-actin used as protein loading controls.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by modified t-test with the Bonferroni correction for comparisons between individual groups; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Discovery of Herbal Medicine for the Prevention of Prehypertension project (K12202) and the Construction of the Basis for Practical Application of Herbal Resources (K12020) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) of Korea to the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM).

References

- 1.Kim J. Y., Park H. J., Um S. H., Sohn E. H, Kim B. O., Moon E. Y., Rhee D. K., Pyo S. Sulforaphane suppresses vascular adhesion molecule-1 expression in TNF-α-stimulated mouse vascular smooth muscle cells: involvement of the MAPK, NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways. Vascul. Pharmacol. (2012);56:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun M., Pietsch P., Schrör K., Baumann G., Felix S. B. Cellular adhesion molecules on vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. (1999);41:395–401. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. Circulation. (2002);105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spagnoli L. G., Bonanno E., Sangiorgi G., Mauriello A. Role of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J. Nucl. Med. (2007);48:1800–1815. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.038661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brien K. D., McDonald T. O., Chait A., Allen M. D., Alpers C. E. Neovascular expression of E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in human atherosclerosis and their relation to intimal leukocyte content. Circulation. (1996);93:672–682. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien K. D., Allen M. D., McDonald T. O., Chait A., Harlan J. M., Fishbein D., McCarty J., Ferguson M., Hudkins K., Benjamin C. D. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. (1993);92:945–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung H. K., Lee I. K., Kang H., Suh J. M., Kim H., Park K. C., Kim D. W., Kim Y. K., Ro H. K., Shong M. Statin inhibits interferon-gamma-induced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Exp. Mol. Med. (2002);34:451–461. doi: 10.1038/emm.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon J. S., Joung H., Kim Y. S., Shim Y. S., Ahn Y., Jeong M. H., Kee H. J. Sulforaphane inhibits restenosis by suppressing inflammation and the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. (2012);84:767–801. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang Y., Lincoff A. M., Plow E. F., Topol E. J. Cell adhesion molecules in coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (1994);24:1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies M. J., Gordon J. L., Gearing A. J., Pigott R., Woolf N., Katz D., Kyriakopoulos A. The expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM, and E-selectin in human atherosclerosis. J. Pathol. (1993);171:223–229. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libby P., Li H. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and smooth muscle cell activation during atherogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. (1993);92:538–539. doi: 10.1172/JCI116620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Printseva O., Peclo M. M., Gown A. M. Various cell types in human atherosclerotic lesions express ICAM-1. Further immunocytochemical and immunochemical studies employing monoclonal antibody 10F3. Am. J. Pathol. (1992);140:889–896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huo Y., Ley K. Adhesion molecules and atherogenesis. Acta. Physiol. Scand. (2001);173:35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S. H., Kim J. H., Park S. J., Bae S. S., Choi Y. W., Hong J. W., Choi B. T., Shin H. K. Protective effect of hexane extracts of Uncaria sinensis against photothrombotic ischemic injury in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. (2011);138:774–779. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang W. K., Sung Y. Y., Kim H. K. Anti-thrombotic and Anti-platelet Activity of Extract from Prunelly vulgaris. J. Life. Sci. (2011);21:1422–1427. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2011.21.10.1422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skottová N., Kazdová L., Oliyarnyk O., Vecera R., Sobolová L., Ulrichová J. Phenolics-rich extracts from Silybum marianum and Prunella vulgaris reduce a high-sucrose diet induced oxidative stress in hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rats. Pharmacol. Res. (2004);50:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu F., Ng T. B. Anti-oxidantive and free radical scavenging activities of selected medicinal herbal. Life. Sci. (2000);66:725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng J., He J., Ji B., Li Y., Zhang X. Antihyperglycemic activity of Prunella vulgaris L. in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Asia. Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. (2007);16:427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouchi N., Kihara S., Arita Y., Maeda K., Kuriyama H., Okamoto Y., Hotta K., Nishida M., Takahashi M., Nakamura T., Yamashita S., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. (1999);25:2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.25.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C. H., Yi H. S, Kim J. E, Heo S. K., Cha C. M, Won C. W., Park S. D. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effect of fractionated extracts of smilacis glabrae rhizoma in human umbilical vein endothelial cell. Korean J. Herbology. (2009);24:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marx N., Neumann F. J., Zohlnhöfer D., Dickfeld T., Fischer A., Heimerl S., Schömig A. Enhancement of monocyte procoagulant activity by adhesion on vascular smooth muscle cells and intercellular adhesion molecule- 1-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. Circulation. (1998);98:906–911. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.9.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. (1993);362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon M. K., Kang D. G., Lee Y. J., Kim J. S., Lee H. S. Effect of Benincasa hispida Cogniaux on high glucose-induced vascular inflammation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Vascul. Pharmacol. (2009);50:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byeon H. E., Park B. K., Yim J. H., Lee H. K., Moon E. Y., Rhee D. K., Pyo S. Stereocalpin A inhibits the expression of adhesion molecules in activated vascular smooth muscle cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. (2012);2:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin P., Tang X., Elloso M. M., Harnish D. C. Bile acids induce adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells through activation of reactive oxygen species, NF-kappaB, and p38. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. (2006);2:H741–H747. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01182.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gosset P., Wallaert B., Tonnel A. B., Fourneau C. Thiol regulation of the production of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 by human alveolar macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. (1999);1:98–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a17.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta A., Rosenberger S. F., Bowden G. T. Increased ROS levels contribute to elevated transcription factor and MAP kinase activities in malignantly progressed mouse keratinocyte cell lines. Carcinogenesis. (1999);11:2063–2073. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.11.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J. G., Oh G. T. The role of peroxidases in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. BMB Rep. (2011);8:497–505. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2011.44.8.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J. S., Kang S. S., Lee K. S., Jang S. Y., Won D. H. Quantitative Determination of ursolic acid from Prunellae Herba. Korean J. pharmacogn. (2000);4:426–420. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pozo M., Castilla V., Gutierrez C., de Nicolás R., Egido J., González-Cabrero J. Ursolic acid inhibits neointima formation in the rat carotid artery injury model. Atherosclerosis. 2006;1:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J. harmacology of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. (1995);49:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ullevig S. L., Zhao Q., Zamora D., Asmis R. Ursolic acid protects diabetic mice against monocyte dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2011);2:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H., Gao M., Ha T., Kelley J., Young A., Breuel K. Prunella vulgaris aqueous extract attenuates IL-1β-induced apoptosis and NF-κB activation in INS-1 cells. Exp. Ther. Med. (2012);3:919–924. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuchiya S., Yamabe M., Yamaguchi Y., Kobayashi Y., Konno T., Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer. (1980);26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C., Chou C., Sun Y., Huang W. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced activation of downstream NF-kappaB site of the promoter mediates epithelial ICAM-1 expression and monocyte adhesion. Involvement of PKCalpha, tyrosine kinase, and IKK2, but not MAPKs. Cell Signal. (2001);13:543–553. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]