Abstract

Objectives

To determine patient characteristics associated with achieving and sustaining blood pressure (BP) targets in the Adherence and Intensification of Medications program, a program led by pharmacists trained in motivational interviewing and authorized to make BP medication changes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with diabetes and persistent hypertension in Kaiser Permanente and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Using two-level logistic regression, baseline survey data from 458 program participants was examined to determine patient characteristics associated with: 1) Discharge from the program with a target BP (short-term success); 2) Maintenance of the target BP over a 9-month period (long-term success).

Results

In multivariable analyses, patients who screened positive for depression or had a higher baseline systolic BP were less likely to achieve short-term success (AOR 0.42 [95% CI: 0.19–0.93], p=0.03; AOR 0.94 [0.91–0.97], p<0.01; respectively). Patients who reported at baseline one or more barriers to medication adherence were less likely to achieve long-term success (AOR 0.50 [0.26–0.94], p=0.03).

Conclusions

Although almost 90% of patients achieved short-term success, only 28% achieved long-term success. Baseline barriers to adherence were associated with lack of long-term success and could be the target of maintenance programs for patients who achieve short-term success.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Diabetes, Questionnaires, Medication adherence

INTRODUCTION

Achieving and sustaining adequate blood pressure control (BP) is critically important for adults with diabetes. For example, in the UKPDS study, achieving mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) levels of 144 mm Hg (vs. 154 mm Hg) led to an absolute risk reduction of 24% in diabetes complications over 10 years, an effect two times greater than intensive blood glucose control.[1] Consequently, countless quality improvement programs and health system interventions have targeted improving SBP. A range of intervention approaches have achieved impressive short-term BP results (i.e., significant reductions during and/or at the conclusion of the intervention).[2–6] In recent years, however, as more researchers examine whether short-term gains are sustained in the absence of maintenance programs, it has become evident that many patients do not sustain improved BP levels after quality improvement programs and interventions finish.[7–9] These findings for BP are consistent with a systematic review of 72 diabetes self-management interventions by Susan Norris and her colleagues that found that while many different diabetes self-management support strategies lead to improvements in mean HbA1c levels among participants, without follow-up, mean HbA1c improvements diminished to clinical insignificance within 6 months of intervention completion.[10]

An important lesson from recent evidence is that for many adults with diabetes improved risk factor control achieved through participation in targeted programs will not be sustained without follow-up support.[8] Understanding patient characteristics associated with failure to achieve short-term improvements in risk factor control as well as to sustain any improvements will inform program efforts to address modifiable patient characteristics to improve both patients’ short-term and long-term success in maintaining good BP and other risk factor control. While numerous cross-sectional studies have explored factors associated with BP medication adherence and control,[11–13] this question has been little examined longitudinally in the context of interventions seeking to improve risk factor control. Accordingly, using data from a cohort of hypertensive adults with diabetes who participated in a clinical pharmacist-led program to improve SBP levels (the results of which have been previously published),[14] we conducted an exploratory cohort study to evaluate:

What patient characteristics are associated with being discharged from a pharmacist-led program with medication adherence issues addressed and achievement of a target blood pressure?

For those who are discharged with a target blood pressure, what baseline patient characteristics are associated with being able to maintain the target blood pressure over the long-term (over a 9 month period, from 90–365 days after discharge)?

METHODS

Previously, we conducted a prospective, multi-site cluster-randomized effectiveness study in three Veterans Affairs (VA) and two Kaiser Permanente (KP) facilities. Sixteen primary care teams (three sites with 2 intervention teams and 2 control teams and two sites with 1 intervention team and 1 control team) were randomized to the Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) program - a program led by clinical pharmacists trained in motivational interviewing-based behavioral counseling approaches and authorized to make BP medication changes – or to usual care. During the intervention period, 945 diabetic patients (with baseline persistent poor BP control and poor medication refill adherence or no evidence of medication intensification) had one or more encounters with a program pharmacist. (See Supplemental File for additional details about eligibility.) The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each of the study sites. Details on the original study are published elsewhere.[14,15]

Survey Administration

Eligibility for the intervention was determined quarterly. A study survey was mailed to patients immediately after eligibility was determined each quarter, approximately 1–2 weeks prior to the distribution of that quarter’s eligibility list to the AIM pharmacist. The survey was administered using a modified Dillman method.[16] For the current cohort study, we restricted the sample of survey respondents to those patients on the 8 intervention teams who were actually contacted by a pharmacist to participate in the program and agreed to participate.

Survey Design

The 10-page survey was constructed by a team with extensive survey development experience and used many well-validated scales, as described below. Newly developed (or modified) questions and scales were pretested with patients and revised as needed prior to use.

Variables

Dependent Variables

Our first dependent variable was whether a patient achieved short-term success as a participant in the AIM program. Short-term success was defined as being discharged from the AIM program with pharmacist documentation that all medication adherence issues had been addressed and achievement of the target blood pressure. The target BP was defined as <135/80 in VA and <130/80 in KP; this could be by home measurement, with a strict protocol, or by clinic measurement. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up, declined further participation in the program, or were enrolled in the program for six or more months without making further progress.

The second dependent variable was whether patients who achieved short-term success were able to maintain this success long term. Long-term success was defined as maintaining an average systolic BP <135 in VA and <130 in KP during a 9 month period after discharge from the program. (Blood pressures were from sites’ usual electronic databases. Blood pressure values obtained in the ER, urgent care, inpatient, and surgery departments were excluded.) The 9 month period was from 90–365 days after discharge. Patients who did not have any blood pressures recorded in the 9 month period were excluded from further analyses.

Independent Variables

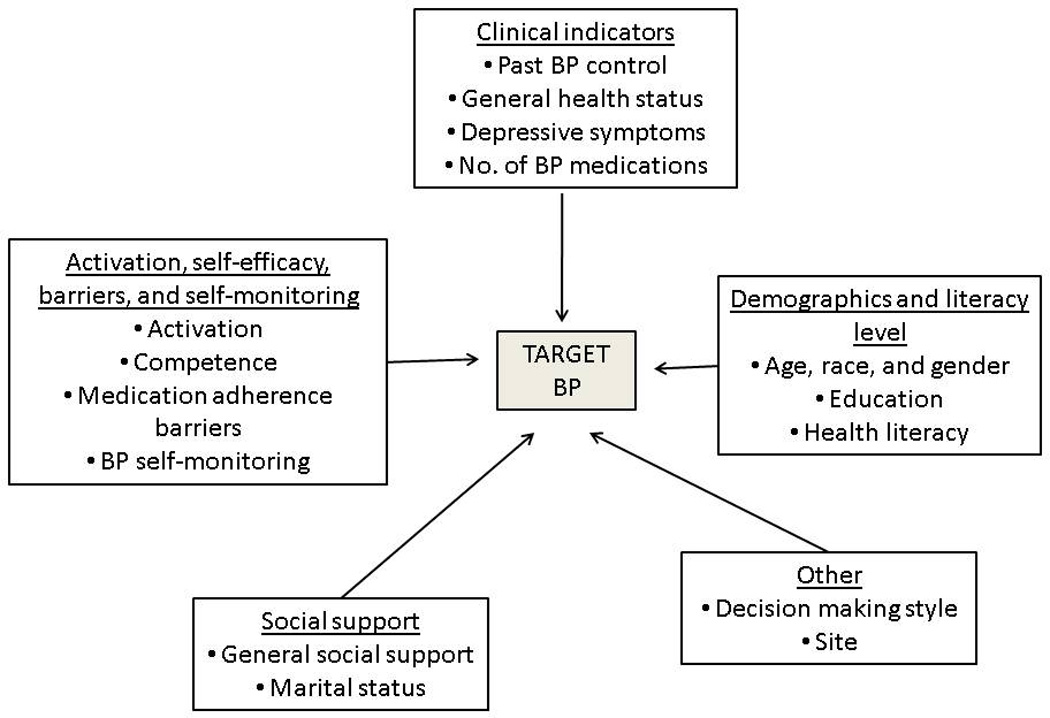

Our conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrates concepts and patient characteristics captured in our survey or automated data that we hypothesized might be associated with short-term and long-term BP success. These are described in detail below.

Figure 1.

Patient activation, self-efficacy, barriers, and self-monitoring

We assessed patient activation using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) developed by Hibbard.[17] This measure assesses an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence for self-management. We modified the questions in this measure to include a neutral category. Patients indicated their level of agreement with statements using a 5-point Likert scale (1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”). Responses on items were rescaled from 1–5 to 0–100 and an activation score was calculated by averaging the responses on the answered items. A score of 100 represented the highest activation level. The scale had high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.88).

We assessed a patient’s competence or self-efficacy level using the Perceived Competence Scale (PCS).[18] The PCS is a validated 4-item scale that measures how competent or able patients perceive themselves to be with respect to managing and controlling BP. Although the original PCS uses a 7-point response scale (1 “Not at all true” to 7 “Very true”), to be consistent with other questions included in the survey we used a 5-point scale (1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”). Reponses on items were rescaled from 1–5 to 0–100, and a score was calculated by averaging responses (minimum of 2 questions had to be answered). A score of 100 represented the highest competence level. The scale had high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.91).

We created an index, containing 10 items, of issues that might keep patients from taking their medication as prescribed, based on prior literature on key factors contributing to poor medication adherence.[19,20] See Table 1. Responses ranged from 1 “Not At All” to 5 “Very Often”. A score, ranging from 10–50, was calculating by summing the responses to the 10 items (all items had to be answered). A score of 10 indicated that a patient reported no barriers to taking medications as prescribed.

Table 1.

Potential medication adherence barriers

| In the past 3 months, to what extent has each of the following issues kept you from taking your blood pressure medication as prescribed? |

% of patients indicating the barrier was an issue (i.e., selected something other than ‘Not at all an issue’) |

|---|---|

| 1. The cost of your medication | 18.2 |

| 2. Difficulties, besides cost, getting your medications filled or refilled | 22.7 |

| 3. Unpleasant side effects when taking your medications | 29.3 |

| 4. Not knowing how or when to take your medications | 18.9 |

| 5. Getting confused because keeping track of so many medications is complicated | 26.9 |

| 6. Feeling that your primary care provider had not fully explained your medications | 24.4 |

| 7. Feeling unsure whether or why these medications were necessary to improve your health | 28.7 |

| 8. Forgetting to take your medications | 56.3 |

| 9. Concern about having to take medications for the rest of your life | 35.4 |

| 10. Worry about long term effects of your medications | 46.0 |

Finally, we asked a single question to assess how often a patient checked their BP during an average week (responses ranged from 1 “Less than once a week” to 5 “Twice a day or more” OR 0 “I do not check my blood pressure at home”). We then collapsed responses 1–5 to create a variable that indicated whether or not a patient did any home monitoring.

Clinical Indicators

Several survey and electronic medical record items were used as clinical indicators: general health status, depressive symptoms, and perceived BP severity or complexity. To assess perceived general health, patients answered the following well-validated general health status question, from the SF-36,[21] to rate their overall health: “In general, would you say your health is 1 “Excellent” to 5 “Poor”. For depression, we measured depressive symptoms using the validated Patient Health Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2).[22,23] Patients rated how often they had 1) been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things; or 2) been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless over the last two weeks. Patients answered the questions using a 4-point response scale, from 0 “Not at all” to 3 “Nearly everyday”. A score was calculated by summing the responses to the two questions (range: 0–6); a score of >=3 indicated a positive screen for depressive symptoms. The scale had moderate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76). Finally, from electronic medical record data, we included 2 measures of BP severity/complexity. First, we used the total number of BP medications that the patient was on at baseline measured by the number of unique BP medications that the patient had fills for during the 120-day period prior to eligibility for the study. Second, we used the patient’s past BP control, defined as the average SBP during the 9 months prior to eligibility for the study.

Social support

Two questions assessed social support. Patients rated their agreement with the statement “I can count on my family or friends to help and support me a lot with taking my medications” on a 5-point scale (1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”). Patients were also asked whether they were married or living with someone.

Demographics and other characteristics

Along with demographics and site of care, we included two other patient characteristics that might be associated with BP success: health literacy level and decision making style. We used a single validated screening question, developed by Chew, to examine whether a patient had inadequate health literacy.[24,25] Patients were asked: “Many people have difficulty reading and filling out forms when they go for medical care. How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” Responses were on a 5-point scale from 1 “Extremely” to 5 “Not at all”. We asked a single question to determine what decision making style a patient was most comfortable with. The five responses ranged from: 1 “I leave decisions about treatment up to my health care provider” to 5 “I make the final decision with little input from my health care provider”).[26,27]

Analyses

Using bivariate analyses, we first examined associations between patient characteristics and short-term success (i.e., achieving the target BP). A two-level multivariable logistic regression model was then constructed (accounting for clustering of patients within teams) to further examine the independent association between a patient characteristic and short-term success, adjusting for other patient characteristics. Variables with a p-value ≤ 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model. Long-term success was examined similarly. (Note: Age, gender, race, and site of care were included in all models, regardless of their association with success in bivariate analyses.) We examined collinearity among the predictors using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and detected no significant multicollinearity. All analyses were performed using STATA11.1 (Stata, College Station, Texas, 2010). The average percent of missing cases for variables was 3%.

RESULTS

Overall, 945 patients had one or more encounters with an AIM pharmacist. (See Figure 2 for flow diagram.) Of the 554 patients (range of patients per site: 89–160) returning a baseline survey, 96 met further exclusion criteria (discharged because of a diastolic BP<60, were on maximum medications, or the programmed ended) and were not included in any analyses. Of the 458 eligible patients with survey data, 399 (87%) achieved target SBP levels by the end of their participation in the program. 63 of the 399 patients with short-term success did not have BP measurements recorded in the 9 month period after discharge and therefore were excluded from the long-term success analyses. As compared to those with BPs in this 9 month period, those without BPs in this period were more likely to be male (79% vs. 66%; p<.05); we found no other differences in demographics or prior SBP level between these groups.

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram

BP = Blood Pressure

*Discharged because of a diastolic BP<60, were on maximum medications, or the programmed ende

Of the 336 patients achieving short-term success and having BP measurements in the 9 month follow-up period, 95 (28%) achieved long-term success. Of note, 75% (180/241) of those patients who were not able to maintain (i.e., achieved short-term success, but not long-term success) did have a lower mean SBP in the 9 month follow-up period than in the 9 months prior to eligibility for the study; however, these SBPs were no longer at or below the target levels of 135 for VA and 130 for KP.

The baseline characteristics of all patients are described in Table 2. For the overall sample (N=458), the mean age was 65.7, 61% were white, the majority were male, and 56% had more than a high school education. Patient characteristics associated with achieving short and long-term success, in bivariate analyses, are also reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between characteristics of diabetic patients in the AIM program (in Kaiser Permanente or the Department of Veterans Affairs) and short/long-term BP success

| Characteristic | Overall | Achieved short-term success† |

Did not achieve short-term success† |

P value* |

Achieved long-term success‡ |

Did not achieve long-term success‡ |

P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 485 | 399 | 59 | 95 | 241 | ||

| Age, mean(SD) | 65.7 (10.2) | 66.1 (10.2) | 62.8 (10.2) | 0.02 | 66.1 (9.8) | 66.6 (10.1) | 0.67 |

| Race, % | |||||||

| White | 61.4 | 63.1 | 49.1 | 0.06 | 60.4 | 66.2 | <0.01 |

| Black | 11.5 | 10.6 | 18.2 | 3.3 | 13.1 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 12.0 | 10.8 | 20.0 | 14.3 | 8.4 | ||

| Other | 15.1 | 15.5 | 12.7 | 22.0 | 12.2 | ||

| Male, % | 67.9 | 68.4 | 64.4 | 0.54 | 62.1 | 68.1 | 0.30 |

| Education level > high school, % | 55.7 | 54.9 | 61.1 | 0.39 | 68.6 | 48.1 | <0.01 |

| Activation, self efficacy, barriers, and self-monitoring | |||||||

| Activation score, mean(SD) | 71.0 (13.4) | 71.5 (13.1) | 67.4 (14.8) | 0.03 | 70.9 (13.4) | 71.4 (12.8) | 0.72 |

| Perceived competence score, mean(SD) | 62.0 (20.9) | 62.1 (21.1) | 61.0 (19.6) | 0.70 | 60.5 (22.1) | 61.3 (20.7) | 0.76 |

| One or more barriers to medication adherence, % | 72.9 | 70.5 | 89.8 | <0.01 | 65.1 | 72.6 | 0.20 |

| Monitor BP at home (any amount), % | 63.6 | 65.4 | 51.7 | 0.04 | 63.3 | 67.1 | 0.52 |

| Clinical indicators | |||||||

| Excellent, very good, good health status, % | 64.7 | 65.5 | 59.7 | 0.39 | 64.1 | 62.9 | 0.84 |

| PHQ-2 positive (≥3), % | 20.5 | 18.1 | 36.2 | <0.01 | 11.8 | 19.3 | 0.11 |

| Prior SBP, mean(SD) | 152.9 (10.4) | 152.2 (9.6) | 157.7 (13.8) | <0.01 | 150.7 (8.5) | 153.0 (9.9) | 0.06 |

| No. of BP meds, mean(SD) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.87 | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.5) | 0.43 |

| Social support | |||||||

| Have support from family or friends, % | 53.7 | 53.8 | 53.5 | 0.96 | 55.1 | 53.6 | 0.81 |

| Married or living with someone, % | 62.8 | 63.1 | 61.4 | 0.81 | 67.7 | 58.6 | 0.12 |

| Other | |||||||

| Somewhat, a little, or not at all confident filling out medical forms, % | 30.2 | 29.5 | 34.5 | 0.44 | 25.8 | 32.1 | 0.27 |

| Preferred decision making style | |||||||

| Shared | 39.6 | 41.0 | 30.4 | 0.17 | 40.9 | 43.1 | 0.93 |

| PCP primarily | 48.5 | 48.0 | 51.8 | 48.9 | 47.4 | ||

| Patient primarily | 11.9 | 11.0 | 17.9 | 10.2 | 9.5 |

P values ≤0.2 included in models; N=336 for the long-term success model (16% (63/399) of the patients with short-term success did not have BP measurements recorded in the 9 month period after discharge and therefore were excluded from the long-term success analyses);

Short-term success was defined as being discharged from the AIM program with pharmacist documentation that all medication adherence issues had been addressed and achievement of the target blood pressure.

Long-term success was defined as maintaining an average systolic blood pressure <135 in VA and <130 in KP during a 9 month period after discharge from the program.

Short-term success model

In the final multivariable model examining short-term success [being discharged from the AIM program with medication adherence issues addressed and achievement of a target BP], patients with higher baseline SBPs were less likely to achieve success (AOR 0.94 [0.91–0.97]; p<.01) as were patients who screened positive for depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2 (AOR 0.42 [0.19–0.93]; p=.03). No other variables were independently associated with short-term success in the multivariable model. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model examining those who achieved short-term success†

| Characteristic* | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.34 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black | 0.35 (0.11–1.07) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.58 (0.21–1.65) | 0.31 |

| Other | 0.75 (0.25–2.22) | 0.60 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref | |

| Male | 1.74 (0.67–4.56) | 0.26 |

| Activation score | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.34 |

| Barriers to medication adherence | ||

| None | Ref | |

| One or more | 0.34 (0.11–1.06) | 0.06 |

| Monitor BP at home | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.62 (0.75–3.50) | 0.22 |

| PHQ-2 positive | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.42 (0.19–0.93) | 0.03 |

| SBP 9 months prior to eligibility (mmHg) | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.01 |

| Preferred decision making style | ||

| Shared | Ref | |

| PCP primarily | 0.68 (0.32–1.46) | 0.32 |

| Patient primarily | 0.84 (0.27–2.60) | 0.76 |

Site of care was also included in the model and non-significant

Short-term success was defined as being discharged from the AIM program with pharmacist documentation that all medication adherence issues had been addressed and achievement of the target blood pressure.

Long-term success model

In the multivariable model examining long-term success [maintaining the target blood pressure during a 9 month period after discharge], patients who reported at baseline one or more barriers to medication adherence were less likely to achieve long-term success (AOR 0.50 [0.26–0.94]; p=.03). Additionally, patients with more than a high school education (AOR 2.30 [1.22–4.34]; p=.01) and of male gender (AOR 2.37 [1.04–5.41]; p=.04) were more likely to maintain their target BP post-discharge. Finally, as compared to White patients, Black patients were less likely to achieve long-term success (AOR 0.24 [0.06–0.97]; p=.046). There were no differences between Hispanic and White patients or other races and White patients. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model examining those who achieved long-term success†

| Characteristic* | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.63 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black | 0.24 (0.06–0.97) | 0.046 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.43 (0.51–3.98) | 0.50 |

| Other | 1.29 (0.57–2.89) | 0.54 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref | |

| Male | 2.37 (1.04–5.41) | 0.04 |

| Education level > high school | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 2.30 (1.22–4.34) | 0.01 |

| Barriers to medication adherence | ||

| None | Ref | |

| One or more | 0.50 (0.26–0.94) | 0.03 |

| PHQ-2 positive | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.80 (0.35–1.84) | 0.60 |

| SBP 9 months prior to eligibility (mmHg) | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | 0.44 |

| Married or living with someone | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.62–2.30) | 0.60 |

Site of care was also included in the model and non-significant

Long-term success was defined as maintaining an average systolic blood pressure <135 in VA and <130 in KP during a 9 month period after discharge from the program.

DISCUSSION

Among this cohort of hypertensive diabetes patients who participated in a clinical pharmacist-directed intervention to improve BP control, almost 90% achieved SBPs at or below target levels by the end of their participation in the program. Only 28% (95/336), however, maintained these good levels in the 9-month period after the program’s conclusion. These findings reinforce the importance for many patients of providing maintenance support to help them sustain gains achieved through participation in more intensive programs. Whereas several studies have found, on average, continued better BP control among hypertensive patients who participated in an intervention compared to control patients, even in these trials large numbers of patients who had achieved BP improvements did not maintain them after the end of the intervention.[7,8] In our study cohort, reporting at baseline one or more barriers to medication adherence, less than a high school education, being female, and being African-American were each independently associated with not sustaining BP improvements achieved through the program. While reporting depressive symptoms at baseline was associated with failure to achieve target BPs by the end of the program, baseline depressive symptoms were not associated with lack of longer-term maintenance of target BP levels among those who initially achieved target BP levels.

Our findings build on numerous studies that have examined cross-sectional associations between patient characteristics and adherence to BP medications and/or good BP control.[11–13, 28–31] Multiple studies have found that African-American patients and patients with less formal education on average have greater odds of having worse BP control.[11–13, 28, 30–32] The association of these patient characteristics and reported barriers to medication adherence with lack of longer-term BP control-- but not with achievement of target BP levels by the end of participating in the intervention --suggests that the pharmacists were able to help patients address the barriers they faced to achieving good BP control during the program but not after the program ended.

Our study found that baseline depressive symptoms were associated with failure to achieve shorter-term BP; this may be because of poorer antihypertensive medication adherence in these patients that we were not able to fully capture in our model.[33, 34] Our study protocol recommended that the pharmacists screen patients for depression at the first visit using the PHQ-2 and recommend talking with their PCPs if they screened positive. A recent RCT found that an intervention among patients with poorly controlled diabetes, coronary heart disease, or both and coexisting depression providing guideline-based, patient-centered management of depression and chronic disease significantly improved both control of medical disease and depression.[35] The lack of an association between baseline depressive symptoms and persistence of achieved gains is in line with another recent study that found that baseline depressive symptoms were not associated with long-term control of BP, A1c, and LDL control among adults with diabetes.[36] Possibly patients’ depressive symptoms resolved over time either because of additional care they received to address their depressive symptoms or because their situations changed. The reason for this pattern of results requires further investigation.

Our study had several limitations. First, our study focused on patients who had adherence problems at baseline or who did not receive medication intensification recently. These patients may be different from patients with poor BP control but who have not had medication management problems. Second, our analysis focused only on those patients who returned a survey and had follow-up blood pressures available. That could raise concerns that we captured more motivated participants in the intervention, and patients who do not return for follow-up care would be those more likely to have missing BP values and may also be those with worse BP control. However, although we only surveyed a subsample of eligible patients, the long-term success rate in the overall population of our study was similar to those included in this analysis. Third, the exact duration of blood pressure maintenance varied for each patient. The shortest possible duration being 90 days and the longest duration 365 days. Finally, our conceptual model was based on available data only. We were unable to examine other potentially relevant patient characteristics such as patient comorbidity because these data were not available in our study dataset.

In this study, reporting at baseline barriers to adherence was associated with lack of long-term success. Such barriers could be the target of maintenance programs for patients who achieve short-term success with an intensive intervention. For example, mechanisms should be put in place to proactively reach out to patient who initially reported barriers to medication adherence, perhaps through automated telephone or some other health information technology outreach,[37–39] to assess whether any adherence barriers have recurred. Additionally, patients with other characteristics associated with difficulties with long-term success could be targeted for similar maintenance programs.

The hallmark of patient-centered care is to deliver care that patients need and want in ways that improve their outcomes. Programs such as AIM take both a population-based and patient-centered approach to care delivery. However, in order to truly improve outcomes, improvements will need to be sustained over time. We are only just beginning to learn for whom maintenance is key, and how best to deliver such maintenance in cost-effective, sustainable ways.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and Pharmacist Collaboration to Improve Blood Pressure Control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;69(21):1996–2002. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishani A, Greer N, Taylor BC, et al. Effect of nurse case management compared with usual care on controlling cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1689–1694. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, et al. Effect of adding pharmacists to primary care teams on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):20–26. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, et al. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1634–1639. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a Pharmacy Care Program on Medication Adherence and Persistence, Blood Pressure, and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter BL, Doucette WR, Franciscus CL, et al. Deterioration of blood pressure control after discontinuation of a physician-pharmacist collaborative intervention. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(3):228–235. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wentzlaff DM, Carter BL, Ardery G, et al. Sustained blood pressure control following discontinuation of a pharmacist intervention. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2011;13(6):431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):561–587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris AB, Li J, Kroenke K, et al. Factors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(4):483–492. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosworth HB, Powers B, Grubber JM, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):692–698. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosworth HB, Dudley T, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):70.e79-70.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heisler M, Hofer TP, Klamerus ML, et al. Study protocol: the Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) study--a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness study. Trials. 2010;11:95. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heisler M, Hofer TP, Schmittdiel J, et al. Improving blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist outreach program in diabetes patients in two-high performing health systems: the Adherence and Intensification of Medications (AIM) cluster randomized controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2863–2872. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. New York: John Wiley & Son, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1644–1651. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to Medications. NEJM. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. Screening for depression and suicidality in a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):839–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, et al. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(9):941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durant RW, McClure LA, Halanych JH, et al. Trust in physicians and blood pressure control in blacks and whites being treated for hypertension in the REGARDS study. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(3):282–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyre AD, Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive medication adherence in an urban health clinic setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9(3):179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostchega Y, Hughes JP, Wright JD, et al. Are demographic characteristics, health care access and utilization, and comorbid conditions associated with hypertension among US adults? Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(2):159–165. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giles T, Aranda JM, Jr, Suh DC, et al. Ethnic/racial variations in blood pressure awareness, treatment, and control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9(5):345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) J. Clin Hypertens(Greenwich) 2002;4(6):393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heckbert SR, Rutter CM, Oliver M, et al. Depression in relation to long-term control of glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids in patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):524–529. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piette J, Kerr EA, Richardson C, et al. Veteran Affairs Research on Health Information Technologies for Diabetes Self-Management Support. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2008;2(1):1–9. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piette JD. Interactive resources for patient education and support. Diabetes Spectrum. 2000;13(2):110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, et al. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care. Interactive information technology in diabetes care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.