Abstract

Background

Increasing use of hospital observation care continues unabated despite growing concerns from Medicare beneficiaries, patient advocacy groups, providers and policy makers. Unlike inpatient stays, outpatient observation stays are subject to 20% coinsurance and do not count towards the 3-day stay required for Medicare coverage of skilled nursing facility (SNF) care. In spite of the policy relevance, we know little about where patients originate or their discharge disposition following observation stays, making it difficult to understand the scope of unintended consequences for beneficiaries, particularly those needing post-acute care in a SNF.

Objective

To determine Medicare beneficiaries’ location immediately preceding and following an observation stay.

Research Design

We linked 100% Medicare Inpatient and Outpatient claims data with the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessments. We then flagged observation stays and conducted a descriptive claims-based analysis of where beneficiaries were immediately before and after their observation stay.

Results

Most patients came from (92%) and were discharged to (90%) the community. Of more than 1 million total observation stays in 2009, just 7,537 (0.75%) were at-risk for high out-of-pocket expenses related to post-observation SNF care. Beneficiaries with longer observation stays were more likely to be discharged to SNF.

Conclusion

With few at risk for being denied Medicare SNF coverage due to observation care, high out-of-pocket costs resulting from Medicare outpatient co-insurance requirements for observation stays appear of greater concern than limitations on Medicare coverage of post-acute care. However, future research should explore how observation stay policy might decrease appropriate SNF use.

Keywords: Medicare, Observation, SNF, Out-of-pocket costs

Introduction

Several studies have documented widespread use and an increasing trend of hospital observation services in recent years among Medicare beneficiaries.(1-3) Ongoing debates over the appropriateness of hospital observation care reveal unintended consequences of the Medicare policy for beneficiary out-of-pocket costs.(4, 5) Public attention to this issue has also intensified amidst a cascade of congressional hearings,(6) lawsuits,(7) public comments,(8) and recently proposed policy changes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).(9)

Observation services represent a “halfway point” between emergency department treatment and full inpatient admission.(10) The CMS defines observation services as a “set of specific, clinically appropriate services, which include ongoing short-term treatment, assessment, and reassessment that are furnished while a decision is being made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital.”(11) In many cases, patients can be diagnosed and treated under observation, then safely discharged, avoiding an unwanted, unnecessary, and costly hospital inpatient stay. Thus, observation services—if appropriately determined and rendered—serve an essential clinical function with obvious benefits for patients while lowering Medicare costs.(12, 13)

However, observation services can also have significant unintended consequences for Medicare beneficiaries. Time in the hospital under observation is billed as an outpatient rather than inpatient service. Thus, beneficiaries can face high out-of-pocket costs from day 1 due to Medicare's 20% outpatient coinsurance. By contrast, inpatient admissions are not subject to any copayments beyond a $1,216 deductible until day 61. Furthermore, days in observation care are not counted toward the 3-day inpatient stay requirement that qualifies a beneficiary for Medicare's Extended Care Benefit which covers subsequent skilled nursing facility (SNF) care.(14) In many cases, patients may not understand the subtle difference between inpatient and observation status and are unaware that they do not qualify for SNF benefits. In these situations, beneficiaries who were not receiving care in a SNF prior to being placed in observation status either forego recommended SNF care post-discharge or pay for it out-of-pocket.(15-17)

Despite these lingering concerns, little is known about the origin and disposition of observation stays. Consequently, it is difficult to assess the scope of the potential impact of observation services on beneficiaries who may require post-acute SNF care. Thus, the objective of this descriptive analysis was to determine the location of beneficiaries both immediately before and immediately after an observation stay.

Methods

Data Sources

We used 100% Medicare outpatient claims data (for institutional providers) to identify hospital observation stays among beneficiaries in 2009. From the 100% Medicare enrollment data for the same period, we obtained information about each beneficiary's date of birth, sex, race and ethnicity, program eligibility (Parts A and B, and periods of enrollment in managed care), vital status (date of death), and place of residence (state, county, and ZIP code). All Medicare enrollment records and claims contain unique identifiers for each beneficiary, which permits a “crosswalk” between the data sets.

Further, we linked all available Medicare claims information (hospital inpatient and outpatient, SNF, home health, and hospice) and the nursing home resident assessment Minimum Data Set (MDS) to create a residential history file for all beneficiaries who experienced an observation stay in 2009. This file allows the tracking of individuals as they transition through various settings in the acute and post-acute care systems.(18)

Study Population

Our study population included all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who were age 65 or older in calendar year 2009, as identified from the enrollment file. We excluded beneficiaries who were younger than age 65 because they have different characteristics and care needs than the rest of the Medicare population,(19, 20) and those who were enrolled in Medicare managed care programs during any month of the year, for whom no claims data are available. Over 30 million beneficiaries (or approximately 60% of all individuals registered in the 2009 Medicare enrollment file) met all inclusion criteria for this analysis.

Identification of Hospital Observation Stays

We followed official coding instructions in the Medicare Policy and Claims Processing Manual to identify observation stays. These depend on both revenue center codes and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System classification.(11) Pertaining to the time period of our study, an observation stay was identified when a revenue code of “general classification category” (Code 0760) or “observation room” (Code 0762) appeared in conjunction with a procedure code of “hospital observation service, per hour” (Code G0378) or “direct admission of patient for hospital observation care” (Code G0379) in a beneficiary's outpatient claim. Where an observation stay was identified, we also counted the total hours for which observation services were provided, as reported in the “service units” field of the claim.(1)

Analytic Approach

For each observation stay identified during the study period, we determined both its origin (where the patient was immediately before the observation stay began) and disposition (where the patient was “discharged” immediately after the observation stay ended). We did this using the Residential History File (RHF), which concatenates Medicare claim dates of service and MDS assessment dates to determine where patients are each day.(18)

To describe the relationship between observation stays and beneficiaries’ subsequent access to SNF care, we tabulated the frequency distribution of disposition of observation stays by origin, and further stratified the analysis by duration (hours) of the observation stay, grouped in 4 categories: within 24 hours; between 24 and 48 hours; between 48 and 72 hours; and 72 hours or longer). All results reported below are based on 2009 data aggregated to the national level. While we conducted analyses over a wider 2007 to 2009 time period, the results were remarkably similar, so we elected to present only the most recent 2009 data here.

Results

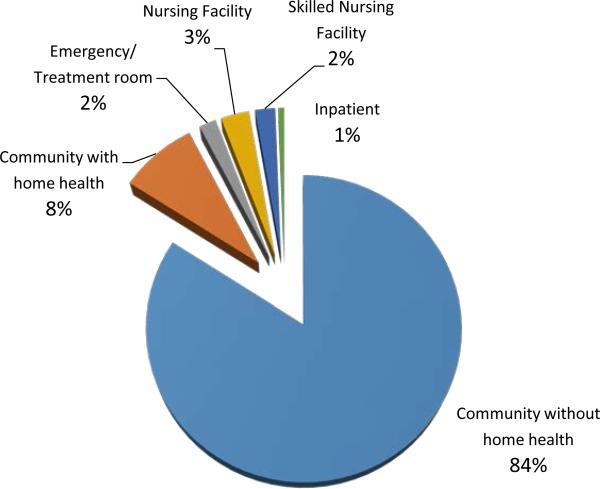

Figure 1 shows the overall distribution of the origin of hospital observation stays. The vast majority (92.4%) of hospital observation stays originated from the community, with 84.1% from community without home health care and 8.3% from community with home health care, in 2009. A relatively small proportion of observation stays (5.1%) came from nursing homes: 21,315 (or 2.1%) from SNF stays (as identified by a SNF claim), and 30,613 (or 3.0%) from nursing facilities (without a SNF claim).

Figure 1.

Origin of Hospital Observation Stays, 2009

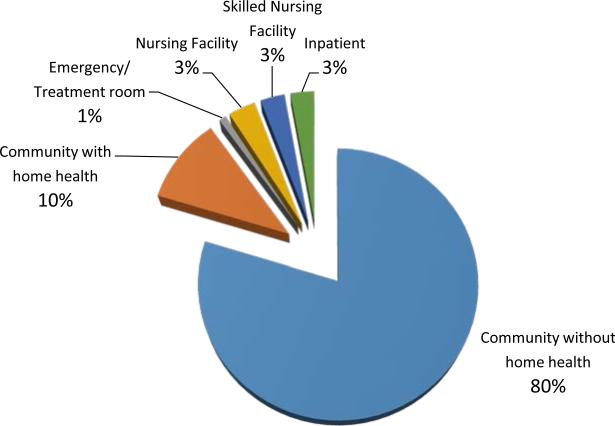

Figure 2 shows the overall distribution of the disposition of hospital observation stays. Consistent with the pattern of their origins, the vast majority (90.1%) of hospital observation stays were discharged to the community (79.7% without home health and 10.4% with home health); 29,324 (or 2.9%) observation stays were discharged to SNFs (with a SNF claim) and 33,061 (3.3%) discharged to nursing facilities (without a SNF claim). Relatively few observation stays were followed immediately by an inpatient admission (2.8%).

Figure 2.

Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays, 2009

Among the observation stays discharged to SNFs (with a SNF claim), 62% originated from a SNF stay (with a SNF claim), 8% originated from a nursing facility, and about 4% originated from an inpatient stay (the distribution of observation stay dispositions conditional on origins is available in Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A758 ). For these individuals, there should be little concern about their access to Medicare-covered SNF care. However, for beneficiaries who were discharged to a SNF (with a SNF claim) following an observation stay that originated from the community (with or without home health care) or from the emergency room, it is likely that they would incur some out-of-pocket expenses for the SNF care received because the time they spent in observation would not count toward the 3-day inpatient stay requirement by Medicare for full coverage of subsequent SNF care. In 2009, this figure is roughly 26% of the 29,324 observation stays discharged to SNF, meaning that just 7,537 (or 0.75%) out of more than 1 million total observation stays are at risk for high out-of-pocket expenses related to post-observation SNF care.

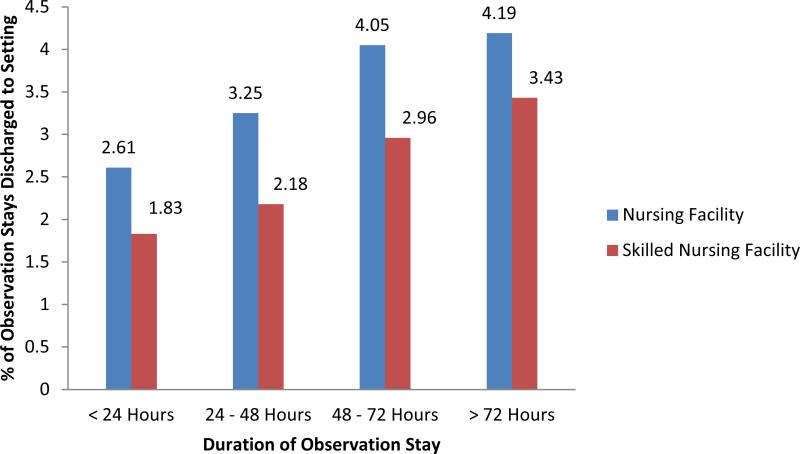

Stratified cross-tabulation results of observation stay disposition by origin, for beneficiaries who were held for less than 24 hours, between 24 and 48 hours, between 48 and 72 hours, and 72 or more hours are presented in Supplemental Tables 2 through 5(Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A759 ). Beneficiaries with a longer observation stay were actually more likely to be discharged to a SNF than those with a shorter observation stay (see Figure 3 and Supplemental Tables 2 through 5, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A759 . column total under “SNF” as disposition). Patients with longer observation stays were also more likely to be discharged to nursing facilities (without SNF care) or to the community with home health care.

Figure 3.

Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays to Nursing Facilities and Skilled Nursing Facilities, by Duration of Observation Stay, 2009

Discussion

While our current analysis is descriptive in nature, the results are informative as they document the scope of the potential financial risk faced by Medicare beneficiaries receiving SNF care following a hospital observation stay. In particular, we find that the overwhelming majority of observation stays originated from, and were subsequently discharged back to, the community. A relatively small proportion of observation stays originated from a Medicare-covered SNF (2%) or a nursing facility without SNF coverage (3%). Presumably the impact of observation stays on these beneficiaries, in terms of care access and financial burden, would be minimal because they were either already receiving Medicare-covered SNF care or covered by Medicaid.

Two groups of Medicare beneficiaries are at the highest potential risk for being denied Medicare-covered SNF care and facing significant out-of-pocket costs. First, the 3.3% of beneficiaries with an observation stay discharged to a nursing home without a SNF claim would likely be subject to high out-of-pocket costs because they would be responsible for paying for their care privately, unless they had Medicaid or other supplemental coverage. Additionally, a subset of the 2.9% of beneficiaries with an observation stay discharged to a SNF with a SNF claim—particularly those whose observation stay derived from the community or the ER—would also be at risk for being denied Medicaid-covered SNF care. In the aggregate, the number of these high-risk beneficiaries is not that large, yet for individuals and their families adversely affected by observation stays the potential financial burden and emotional stress could be substantial. Thus, the impact of denied SNF coverage on total Medicare spending would be small even if Medicare covered those SNF stays irrespective of the preceding observation care episode in the hospital. However, any changes to Medicare payment policy have the potential to dramatically alter practice patterns. For example, eliminating the 3-day inpatient stay rule would likely lead to an increase in discharges from observation to SNF. These results also suggest that the unintended consequences associated with observation services are likely to accrue disproportionately in the form of high out-of-pocket costs resulting from Medicare's outpatient co-insurance requirement, which kicks in from day 1 of an observation stay rather than limitations on Medicare coverage of post-acute SNF care. Since recent reports from the Office of the Inspector General(2) and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (21) suggest that observation use has continued to increase, even more individual patients and families are likely to have experienced these complications. It is likely that those with Medigap supplemental coverage or those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid may be better insulated from the outpatient coinsurance associated with observation stays.

For the vast majority of observation patients who came from the community and were discharged to settings other than a SNF, we are unable to determine how many of them would have needed and received SNF care had their observation stay been treated as inpatient rather than outpatient. It is reasonable to suppose that, given the expectation of no SNF coverage, beneficiaries discharged from observation stays would be more likely to forego SNF care, rather than pay such a large sum out-of-pocket. However, a recent report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General indicates that Medicare improperly paid for 91.7% of the 25,245 Medicare beneficiaries who received SNF care following an observation stay in 2012, while the remaining 8.3% paid an average of $10,503 per person out-of-pocket.(2) This finding suggests that CMS may not rigorously enforce the 3-day inpatient stay requirement for Medicare's Extended Care benefit. It also suggests that most observational discharges who forego SNF care due to fear of high out-of-pocket costs may have had their care paid for. Because we do not know the preferences and needs of observation stay patients discharged back into the community, we cannot speculate as to how many additional beneficiaries would utilize SNF care were the 3-day inpatient stay requirement formerly waived.

Our results also indicate that care transitions for beneficiaries with longer observation stays are different from those with shorter observation stays. Beneficiaries with longer observation stays were more likely to be discharged to a nursing facility or to the community with home health care. A similar association was observed between the duration and origin of observation stays. It is plausible that beneficiaries with a prolonged observation stay in the hospital (especially those patients staying 3 or more nights without knowing their outpatient status) were more likely to believe that they would qualify for Medicare-covered SNF care. This suggests that higher acuity patients are disproportionately affected by adverse consequences of the fragmented payment mechanisms for outpatient services and SNF care, and their experiences should be scrutinized further in additional research.

The current analysis is purely descriptive and narrowly focused on pathways of care. Although we characterized both the origin and disposition of observation stays, we were unable to fully assess the impact of observation stays on beneficiaries’ access to SNF care or their out-of-pocket expenses for services received but not covered by Medicare since the claims data do not report out-of-pocket expenditures. Nor can we know for sure if patients were admitted to SNF but did not generate a Medicare claim or even an MDS record, because they would have left very quickly after learning they were paying privately for care.

It should also be noted that the disposition status of observation stays reported here refers to the patient's location immediately after observation, that is, where the patient was the day right after the observation stay ended. Future analysis should consider extending the follow-up window after the observation stay discharge date (e.g. within 30 days) and examining subsequent patient outcomes such as functional status, hospital admission, and mortality. Future research might also model the observational discharges using multinomial logistic regression, which would be able to control for a wide variety of hospital and patient characteristics, including specific diagnoses.

Finally, while we report on 2009 data, the health care landscape has changed dramatically since then with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Hospitals are now being penalized for excessively high readmission rates and are being incentivized to shift towards value-based payment and accountable care organizations, both of which could potentially motivate a further increase in hospitals’ use of observation services in lieu of short-stay admissions. To address these concerns, and the risks to Medicare beneficiaries we describe here, CMS has issued a proposed rule making any hospitalization lasting less than 2 midnights an observation stay and any hospitalization lasting beyond 2 midnights an inpatient admission. It is unclear if this is the best approach to reducing the unintended consequences of Medicare payment policy for observation services and SNF care. Accordingly, it is important for future research efforts to gauge the full impact of observation stays on Medicare beneficiaries’ access to acute and post-acute care as well as its financial implications, to ensure that beneficiaries receive the care they need and are not subjected to unnecessary financial risk because of a hospital administrative billing decision.

List of Supplemental Tables (online only)

Supplemental Table 1 Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays, by Origin, 2009

Supplemental Table 2 Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays with Duration of Less Than 24 Hours, by Origin, 2009

Supplemental Table 3 Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays with Duration of At Least 24 hours but Less than 48 Hours, by Origin, 2009

Supplemental Table 4 Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays with Duration of At Least 48 Hours but Less than 72 Hours, by Origin, 2009

Supplemental Table 5 Disposition of Hospital Observation Stays with Duration of 72 or More Hours, by Origin, 2009

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was funded by the Retirement Research Foundation (Grant No. 2011-066), the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. P01AG027296) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. 5T32H000011-27). The Medicare enrollment and claims data used in this analysis were made available through a data use agreement (DUA 21845) authorized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

References

- 1.Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1251–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. Epub 2012/06/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Inspector General . Memorandum Report: Hospitals’ Use of Observation Stays and Short Inpatient Stays for Medicare Beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. Washington: DC2013 [updated July 29, 2013; cited 2013 August 3]; Available from: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehy AM, Graf B, Gangireddy S, Hoffman R, Ehlenbach M, Heidke C, et al. Hospitalized but Not Admitted: Characteristics of Patients With “Observation Status” at an Academic Medical Center. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8185. Epub 2013/07/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baugh CW, Schuur JD. Observation care--high-value care or a cost-shifting loophole? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):302–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1304493. Epub 2013/07/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachter RM. Observation Status for Hospitalized Patients: A Maddening Policy Begging for Revision. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7306. Epub 2013/07/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Medicare Advocacy Congressman Joe Courtney and Center for Medicare Advocacy Hold Congressional Briefing on Observation Status. 2011 [cited 2012 April 13]; Available from: http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/2011/10/24/congressman-joe-courtney-and-center-for-medicare-advocacy-hold-congressional-briefing-on-observation-status/

- 7.Morgan D. Medicare beneficiaries sue U.S. over hospital stays. Reuters; 2011 [cited 2012 April 13]; Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/03/us-usa-medicare-lawsuit-idUSTRE7A283420111103.

- 8.Center for Medicare Advocacy Déjà Vu All Over Again: CMS Decides (Again) Not to Decide About Observation Status. 2012 [cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/deja-vu-all-over-again-cms-decides-again-not-to-decide-about-observation-status/

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Federal Register. 78(91) Proposed Rules [Pages 27644-27650] [FR Doc No: 2013-10234]. 2013 [updated May 10, 2013; cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-05-10/html/2013-10234.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downey C. EDTUs: Last Line of Defense Against Costly Inpatient Stays. 2001 [cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: http://www.managedcaremag.com/archives/0104/0104.edtu.html. [PubMed]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Claims Processing Manual (Pub 100-04): Chapter 4 - Part B Hospital. 2013 [updated June 7, 2013; cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf.

- 12.Baugh CW, Venkatesh AK, Hilton JA, Samuel PA, Schuur JD, Bohan JS. Making greater use of dedicated hospital observation units for many short-stay patients could save $3.1 billion a year. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2314–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0926. Epub 2012/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero A, Brown C, Richards F, 3rd, Collier P, Jentz S, Michelman M, et al. Reducing unnecessary medicare admissions: a six-state project. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14(3):143–50. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181a340c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare—Ask. 2011 (CMS Product No. 11435) [updated February 2011; cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: http://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.

- 15.Edelberg C. Medicare sees increase in observation payments. ED Manag. 2009;21(11):123–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffe S. Growing number of patients find a hospital stay does not mean they're admitted. Kaiser Health News. 2010 [cited 2013 August 5]; Available from: http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2010/September/07/hospital-observation-care.aspx.

- 17.Ross EA, Bellamy FB. Reducing patient financial liability for hospitalizations: the physician role. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):160–2. doi: 10.1002/jhm.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, Miller SC, Mor V. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents' long-term care histories. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 Pt 1):120–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01194.x. Epub 2010/10/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foote SM, Hogan C. Disability profile and health care costs of Medicare beneficiaries under age sixty-five. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):242–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.242. Epub 2002/01/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy J, Tuleu IB. Working age Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities: population characteristics and policy considerations. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2007;30(3):268–91. Epub 2008/02/02. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission A data book: Health care spending and the Medicare program. 2012 [updated June 2012; cited 2013 August 17]; Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun12DataBookEntireReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.