Abstract

Objectives

Some studies have reportedan association between depression or serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) antidepressant use and osteoporosis. This association raises concern about the widespread use of antidepressants in older adults and suggests the need to reevaluate this practice. This review examines the association of both depression and antidepressant use with bone health in older adults and the implications for treatment.

Design

A systematic review of studies of the association between depression or antidepressants and bone health in older adults.

Setting

All studies that measured depression or antidepressant exposure and bone mineral density (BMD).

Participants

Adults aged 60 and above.

Measurements

Age, site of BMD measurement by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), measure of depression or depressive symptoms, association between BMD changes and depression or antidepressant use.

Results

Nineteen observational studies met the final inclusion criteria; no experimental studies were found. Several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies found that depression or depressive symptoms were associated with decreased BMD. Few studies and only two longitudinal studies addressed the association between SRI antidepressant use and a decrease in BMD and they had conflicting results.

Conclusion

Depression and depressive symptoms are associated with decreased bone mass and accelerated bone loss in older adults; putative mechanisms underlying this relationship are discussed. There is insufficient evidence that SRI antidepressants adversely affect bone health.Thus, a change in current recommendations for the use of antidepressants in older adults is not justified at the present time. Given the high public health significance of this question, more studies are required to determine whether (and in whom) antidepressants may be deleterious for bone health.

Keywords: depression, antidepressants, BMD, older adults

INTRODUCTION

At least one in seven community-dwelling older adults is prescribed an antidepressant.1Concerns have been raised about the safety of serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SRI) antidepressants in older adults,2 particularly whether these medications may increase risk for osteoporosis, falls and fractures.3-6 In this review, we examine the putative bone loss risk associated with the use of SRIs, using the term to encompass selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Preclinical research has shown that serotonin influences the skeleton. Osteoclasts express serotonin receptor subtypes 2A, 2B and 2C;7 osteoblasts express subtypes 1A, 1B, 1D, 2A and 2B;7,8 and osteocytes express subtypes 1A and 2A.7,9,10 Osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes also express the serotonin transporter which is the primary target for SRIs.7-9 The biological plausibility of SRI-associated bone loss has been demonstrated in preclinical and rodent studies inhibiting the serotonin transporter via fluoxetine administration and with null mutations in the gene encoding for the transporter.7,11

Decreased bone mass and falls are the two major determinants of fractures. Depression has been linked to low bone mass5 and SRIs have been linked to falls, bone loss, and fractures.4,12-14 A recent meta-analysis12 reported SSRI use being associated with a significantly increased risk of fractures (RR = 1.72). If SRIs do induce fractures at this rate, this represents $2.25 billion yearlyaof preventable health care costs, in addition to human and indirect economic burdens. Therefore, whether antidepressants increase the risk of falls or cause bone loss is a public health concern.Several reviews4,12-14 have addressed the relationship among depression, antidepressant use, falls, and fractures. To our knowledge, no published review has focused on the relationship between depression or antidepressant use and bone mineral density (BMD). In doing so, we provide a translation of the current literature and treatment implications regarding antidepressant use in older adults and recommendations for research.

We consider the Bradford Hill criteria15 for causation essential when studying whether depression or antidepressant use are associated with accelerated bone loss. These criteria propose examining the strength and specificity of an association. They also call for consistency or finding that the association has been observed repeatedly by different people, in different situations, locations and times. They affirm the importance of temporality, biological gradient (i.e. dose response curve), biological plausibility, coherence with the natural history and biological facts, experiment to obtain evidence and making judgment by analogy.

The implications of definitely establishing causation between depression and decreased BMD would include adding depression as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Furthermore, a definitive causal connection between SRI antidepressant use and decreased BMD would call for changing the current prescribing guidelines for treatment of depression in older adults.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We followed the guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.16A research librarian conducted a detailed systematic biomedical literature search in PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews, PscyhInfo and Clinical trials.gov starting from the inception of the database start date to September 2013. We also performed a selective manual search of reference list to identify relevant publications and used the authors’ knowledge of the literature to obtain additional references. The controlled vocabulary of each database and plain language was used in creating a search strategy for the terms Depressive Disorder; Depressive Disorder, Major; Depression; Osteoporosis, Bone Density. The age range was used from young adult to very old to prevent exclusion of possibly eligible studies and then the age exclusion criteria were applied. The final search results were limited to human studies and English language using the database supplied limits.

Selection Criteria

Exclusion criteria included age below 60 years. In case an age range was provided, the mean age cutoff for eligibility to the study was set at 60 years. When not provided, mean age was calculated and then rounded up to the nearest year. Since dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold-standard diagnostic tool for measuring BMD, we excluded studies that measured BMD by ultrasound. Studies that only measured fracture as an outcome were also excluded. We set the inclusion criteria for the study sample at N ≥ 100,as smaller studies are underpowered to detect small to medium effect size and their results are not stable, their inclusion would lead to false negative or positive results.17Antidepressants including SSRIs and SNRIs were included. No restrictions were applied to the measurement tool for depression with inclusion of self-reports.

Data collection and extraction

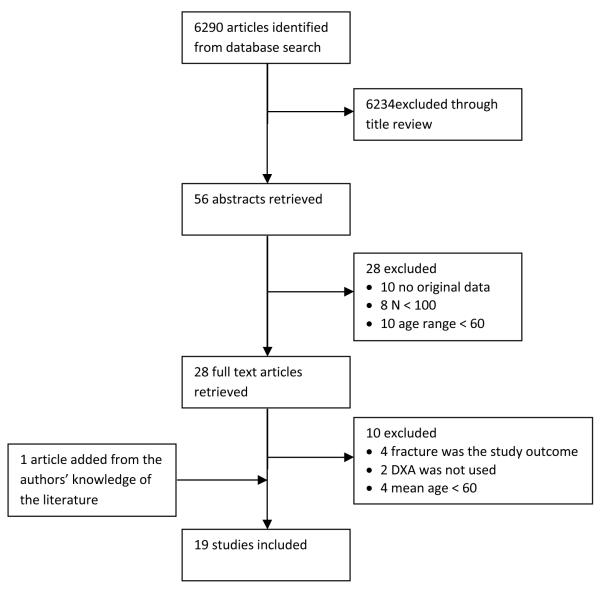

The following data were extracted from tables and text: First author and publication year, sample number, age range and mean age, study design, site of BMD measurement, scale used for assessment of depressive symptoms (or depressive disorder when applicable), presence or absence of an association between depression and a decrease in BMD, presence or absence of an association between SRI use and a decrease in BMD. Two reviewers (MS and MG) conducted independent title, abstract and full text reviews to determine eligibility. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion with (EL). (MG) extracted data from eligible studies. A flow chart summarizing the article selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing review process for identification of eligible studies.

RESULTS

Our search strategy identified 6,290 articles, 6,234 of which were excluded after an initial title review. Twenty eight additional articles were excluded after a review of abstracts. Ten additional articles were excluded after full text review and one article was added resulting in a total of 19 articles included in this review, which are summarized in Table 1. Two reports18,19 were generated from the same study and all the identified studies are observational (cross-sectional, longitudinal, or case-control) as no randomized controlled trial was found. One study20 contained both a cross-sectional and a longitudinal analysis, however only the cross-sectional analysis was included as part of this review since neither the age range nor the mean age were provided for the longitudinal sample.

Table 1.

Systematic Review

| Author | Population (N) |

Age range ( mean age) |

Study Design | Site of BMD measurement |

Assessment of Depressive symptoms |

Decreased BMD associated with depression |

Decreased BMD associated with SRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schweiger et al.211994 |

137 men and women |

Age > 40 (mean = 61) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine | DSM III -R criteriaa |

+ | NA |

| Whooley et al.221999 |

7,414 women | Age ≥ 65 (mean = 73) |

Cross sectional | Hip and lumbar spine |

15 item GDS ≥ 6 |

- b | NA |

| Reginsteret al.231999 |

121 women | Age 48-77 (mean = 63) |

Cross sectional | Spine, hip and femoral neck |

GHQ-28 > 5 | - | NA |

| Robbins et al.242001 |

1,566 men and women |

Age ≥ 65 (mean = 74) |

Cross sectional | Total hip | 10- CES- Dm≥ 10 |

+ | NA |

| Ensrud et al.332003 |

8,127 women | Age >65 (mean = 77) |

Cross sectional | Proximal femur | 15- GDS≥6 | NA | - |

| Whooley et al.302004 |

100 men | Age >50 (mean = 67) |

Longitudinal, 3.6 years |

Lumbar spine and total hip |

15- GDS≥6 | - | NA |

| Cauley et al.342005 |

5,995 men | Age ≥65 (mean = 74) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine and proximal femur |

NA | NA | + |

| Wong et al.252005 |

1,999 men | Age 65-92 (mean = 72) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine, total hip and total body |

(Chinese) GDS ≥ 8 |

+ | NA |

| Diem et al.192007 |

2,722 women | Age>65 (mean = 78) |

Longitudinal, 4.9 years |

Total hip | 15- GDS≥6 | NA | + |

| Diem et al.182007 |

4,177 women | Age > 69 (mean = 76) |

Longitudinal, 4.4 years |

Total hip | 15- GDS≥6 | + | NA |

| Haney et al.352007 |

5,995 men | Age ≥ 65 (mean = 74) |

Cross sectional | Femoral neck, greater trochanter and lumbar spine |

SF-12 MCS | NA | + |

| Richards et al.362007 |

5,008 men and women |

Age > 50 (mean = 65) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine and hip |

SF-12 MCS and MHI-5 |

NA | + |

| Silverman et al.262007 |

3,798 women | Age 31-80 (mean 66.7) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine | 15- GDS≥6 | + | NA |

| Whitson et al.272008 |

5,827 men and women |

Age > 50 (mean = 66) |

Cross sectional | Lumbar spine and femoral neck |

SF-36 MCS and MHI-5 |

- | NA |

| Spangler et al.312008 |

6,441 women | Age 50-79 (mean = 64) |

Longitudinal, 3 years |

Hip, lumbar spine and whole body |

Burnam's scale score ≥ 0.06 |

- c | - |

| Williams et al.202011 |

7,470 women | Age 20-93 (mean= 60) |

Cross-sectional | Forearm | HADS ≥ 8 | - | NA |

| Bolton et al.322011 |

6,820 women 20,247 matched controls |

Age >50 (mean = 70) |

Case-control | Lumbar spine, femoral neck, greater trochanter and total hip |

ICD-9 or ICD -10a |

- | + |

| Erezet al.282012 |

128 women | Postmenopausal age (mean 63) |

Cross sectional | Spine, right and left hip |

SRDS | + | NA |

| Diem et al.292013 |

2,464 men | Age ≥ 68 (mean = 76) |

Longitudinal 3.4 years |

Total hip | 15- GDS≥6 | + | NA |

study assessing depressive disorder, not symptoms

except in women with highest tertile BMI

when antidepressant users were excluded, association is positive

= positive association,

= no association

NA= Not applicable, BMD= Bone mineral density, SRI= Selective reuptake inhibitor, GDS= Geriatric Depression Scale, GHQ= General Health Questionnaire, CES-Dm= Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, MCS= Mental Component Score, MHI-5= Mental Health Inventory 5, HADS= Hospital Anxiety, ICD= International Classification of Disease SRDS= Self Rating Depression Scale

Depression and BMD

One of nine20-28 cross-sectional studies used DSM III-R diagnostic criteria as opposed to a self-report questionnaire. This study showed a positive association between a diagnosis of DSM major depressive disorder and a decrease in BMD at the lumbar spine in men and women21. Two studies of post-menopausal women26,28 and one study of men25 showed a positive association between depressive symptoms and a decrease in BMD. Another study 24 showed similar results, particularly with Caucasian women. Among the four studies that did not find an overall association between depressive symptoms and a decrease in BMD,20,22,23,27 one study22 found that depressive symptoms were associated with a decrease in BMD in women with the highest tertile of body mass index (BMI).Another study20 found no association between depressive symptoms and unadjusted BMD, butadjusted BMD (for variables such as smoking status, physical activity calcium and caffeine intake among others) was lower for men or for heavier women with depressive symptoms. Another of the negative studies23 used the General Health Questionnaire that assesses susceptibility to depression, rather than depressive symptoms or a depressive disorder.

Two18,29 of four longitudinal studies18,29-31 reported that depressive symptoms were associated with decline in BMD at the total hip. One of these studies18 found that the number of depressive symptoms in a sample of women was correlated with rates of bone loss. In the other positive longitudinal study,29 depressive symptoms in men were associated with lower BMD with and without adjustment for medication use. In one of the two negative longitudinal studies,30 participants were men with a depression prevalence of 3.1% and only four participants with elevated depression score on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) ≥6 had follow up BMD, resulting in an unstable finding and limited power. The other negative longitudinal study did not find an overall association in postmenopausal women between depression and changes in BMD. However, when antidepressant users were excluded, depression was associated with greater declines in whole body BMD.

The only case-control study used diagnoses made by non-psychiatrists based on the International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10.32 This approach may introduce considerable methodological bias (due to over-, under- or misdiagnosis). This study did not find an association between depression and decreased BMD but it found a positive association between SRI use and a decrease in BMD.

Antidepressants and BMD

Four cross sectional studies33-36 assessed the association between antidepressant use and a decrease in BMD. One study in women that did not distinguish between SSRI or tricyclic antidepressants33(TCA) did not show an association between antidepressant use and decreased BMD. Of the other three studies, two34,35 showed that SSRI but not TCA use was associated with lower BMD and the third 36found that SSRI use was associated lower BMD at the hip. Two longitudinal studies assessed the association between antidepressant use and changes in BMD over time. In one study in women, SSRI but not TCA use was associated with greater declines in BMD at the total hip;19 when participants with higher levels of self-reported depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 6) were excluded from the analysis, the rate of hip bone loss remained higher in SSRI users than that in nonusers, although the magnitude of the difference between the two groups was less pronounced.The other longitudinal study reported that antidepressant use was not associated with change in BMD at hip, spine or whole body, and in an analysis that only included SSRIs, there was no association between SSRI use and change in BMD.31

DISCUSSION

Osteoporosis is a major economic and human burden. Research to identify risk factors for osteoporosis could help in the reduction of its incidence, resulting in a significant public health benefit.

The preponderance of observational research findsthat depression is associated with lower BMD. However, there is an important caveat to this observation: in all but one study, “depression” was defined based on self-reported depressive symptoms as opposed to a diagnosis. Depressive symptoms tend to be common37in medically ill older adults, and whether these symptoms are an appropriate proxy to assess the influence of depressive disorders on bone metabolism is questionable. Still, the unique study that examined clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder showed a positive association with lower BMD.

The observational studies that have assessed the relationship between antidepressants and BMD suggest that antidepressant use is associated with lower BMD. This association is reported with SRIs but not TCAs, which suggests that serotonergic pathways are implicated in this relationship. However, these two classes of antidepressants are generally used for different reasons: SSRIs are prescribed for the treatment of depression and anxiety, while TCAs are prescribed at sub-antidepressant doses for chronic pain and other somatic complaints. Therefore, the observed antidepressant class-specific effects cannot provide causal inference.The strongest evidence of SRI effects on bone loss come from a single longitudinal study.19Interestingly, a recent study of middle aged women initiating antidepressants did not find a significant decrease in BMD in new users of SSRIs or TCAs. Although the patient mean age (49) was younger than our target older adult population, this study has several strengths as compared to the other longitudinal studies: multiple annual BMD measurements, annual medication use updates, study subjects were new users of antidepressants, which helps reduce potential confounding of long term antidepressant use.38

Potential pathways for the association between depression, antidepressants and bone health

Depression is associated with a worsening of virtually every aging-related medical illness or organ system pathology.39 Many of the putative pathways mediating this association affect bone metabolism. Depression appears to cause alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal(HPA) axis40 and an increase in inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)41 implicating these potential links in the association between depression and bone health. Another factor to consider is 25-hydroxyvitamin D, such that low levels could lead both to depression and lower BMD; a detailed discussion of this putative link is beyond the scope of this review, but it can be found elsewhere.42 Still other potential pathways involve insulin-like growth factor, thyroid and parathyroid hormones, the sympathetic nervous system, or behavioral changes.

One way to examine mechanistically the effects of SRIs on bone metabolism is by measuring bone turnover markers (BTMs). BTMs are products released during bone matrix synthesis or degradation and they can be measured in the serum and urine. To date, only two prospective clinical studies have examined the relationship between BTMs and antidepressant use. In both studies, BTMs were measured pre and post treatment. In the first study that involved a small number of premenopausal women, treatment with escitalopram was associated with a significant decreased of the bone resorption marker, but only in participants whose depression improved.43 In the second study that involved older (age ≥60) men and women,we found that treatment with the SNRI venlafaxine was associated with significantly increased levels of the bone resorption marker, but only in participants whose depression did not remit.44 Further, a bone formation marker did not change in the overall group, but it significantly decreased in individuals genetically defined as having high transcription of the serotonin transporter together with low transcription of the serotonin 1B receptor, a receptor known to be involved in bone formation.45These preliminary results suggest that antidepressant treatment leading to remission of depression may have a positive effect on bone homeostasis, whereas unsuccessful antidepressant treatment may have no effect (as in the first study) or deleterious effects on resorption (as in the second study). The genetic results also suggest that differences in central and peripheral serotonin receptor populations may define individuals at greater or lesser risk of SRI-induced bone loss; this implication is discussed further in “recommendations for research” below.

Does depression cause osteoporosis?

It is useful to apply the Bradford-Hill criteria15 to summarize the evidence for causation between depression or SRI use and decreased bone density. For the association between depression and BMD decrease, there is biological plausibility to support causation as evidenced by the preclinical research showing the influences of serotonin on bones.7-9There appears to be a biological gradient (“dose-response”) linking worsening symptoms to more significant decreases in BMD. However, temporality, specificity, and strength are difficult to establish for this association between depression and BMD given the comorbidities that contribute to bone loss and that are usually present in the elderly population. These data, while not definitive, add osteoporosis to the list of age-related illnesses (including dementia, cardiac and cerebrovascular disease, and cancer) that appear to be accelerated or to have their mortality and disability increased by depression.39 This association between depression and decreased BMD leads us to conclude that depression should be considered a possible risk factor for osteoporosis that deserves further inquiry and consideration into whether older adults with depression should have routine osteoporosis screening.

Do antidepressants cause osteoporosis?

We found comparatively little evidence supporting the hypothesis that SRI antidepressants accelerate bone loss. For the association between SRI use and BMD decrease, there is little evidence to support causation. First, the data have not been consistent. Second, the strength and specificity of the association is questionable given the possible confounding by indication that is discussed above. Finally, while there is biological plausibility to explain how SRI could cause bone loss, there are no experimental studies to support a causal relationship.Overall, this degree of evidence satisfies almost none of the Bradford Hill criteria15 for evaluating strength of evidence: it is inconsistent and not supported by randomized studies. Furthermore, there is little to validate temporality or coherence.

Implications for treatment

Existing treatment guidelines for antidepressants in older adults should not, in our opinion, be altered by the observational data regarding SRIs and bone loss. SRIs remain first-line treatment when pharmacological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders is indicated. In older adults, antidepressants are effective in the treatment of depressions that are of longer duration and at least moderately severe.46 Additionally, when short-term treatment with an SRI antidepressant leads to remission of late-life depression, long term maintenance treatment prevents recurrence.47 There are many evidence-based psychosocial approaches for late-life depression -- including cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, and guided self-help-- and these nonpharmacologic treatment options are favored in cases of milder depression.48

In our opinion, the known risks of untreated depression in older adults outweigh the inconclusive long-term risks of antidepressants, such as low bone mass. Thiscareful consideration of antidepressant risk-benefit ratio includes factoring in the benefits of treating depression that would otherwise amplify disability, burden caregivers, undermine treatment adherence and healthy lifestyle choices, and lead to suicide or hasten mortality. Patients and family will appreciate a clinician who can clarify these issues and guide them in making a treatment decision.

Recommendations for research

The hypothesis that SRIs induce or accelerate bone loss has not been adequately tested. We argue that it could and should be tested. While observational studies are often ideal for identifying adverse effects of medications, a prerequisite is that the adverse effect is different than the disease for which the medication is prescribed.49Otherwise, observational studies are confounded by indication, leading to questions such as, “is it the antidepressant, or the underlying reason for which the antidepressant was prescribed, that accelerates bone loss?” Given that depression and other types of emotional distress (particularly anxiety) may accelerate bone loss, confounding becomes most problematic in the interpretation of the results. It is noteworthy to point out a feature of the well-designed observational study previously discussed38 which includes new users of antidepressants as a way to reduce confounding.50

Genetic studies (e.g., investigating functional polymorphisms in serotonin and other genes involved in bone formation and resorption pathways) could clarify who is at highest risk for bone loss and why, potentially within observational studies - as well as randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Such pharmacogenetics strategies are increasingly applied in an effort to personalize medicine with published guidelines for specific gene-drug relationships.51 In an observational study, if individuals with certain functional serotonin-related genotypes have an increased rate of bone loss in the context of SRI use, but no increased rate in the absence of SRI use, this could provide causal inference, sometimes called Mendelian randomization. Limitations inherent to this design have been previously described;49 another is that a pre-requisite for such a design is the availability of genetic data as well as longitudinal studies data on antidepressant use and bone changes. If further, well-constructed longitudinal studies find a link between SSRI use and bone loss, then RCTscould provide a definitive answer. Change in bone mass can be objectively and specifically measured as an outcome. Older adults with a depressive disorder could be randomized to an SRI vs. a non-SRI antidepressant and then followed longitudinally for a sufficient length of time to measure bone health changes. As treatment of depression in older adults needs to be long-term to prevent relapse, such a clinical trial should exceed the typical 6-12 weeks duration of acute clinical trials to capture potential long-term effects of medications on bone health. Alternatively, since many older adults are already receiving SRIs without a clear indication,52 a study could randomize them to continuation vs. discontinuation of their medication and follow them longitudinally. Finally, a study could randomize on a system level (with practices treating depression with SRIs vs. non-SRIs preferentially). These study designs could be ethically done,consistent with prior clinical trials in late-life depression.

Conclusion

For clinicians, patients, families, and policy-makers, in terms of bone health, we recommend that the evidence thus far should not deter clinicians from using SRI antidepressants to treat late-life depression. For researchers, our review emphasizes the discrepancy between the small amount of literature including the absence of experimental studies and the implications for clinical care and the safety and quality of life of older adults. With the relationship between antidepressant use and bone loss remaining unclear, future research to clarify this relationship has great public health significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosures: Drs. Gebara, Shea, Teitelbaum, Reynolds and Müller and Ms. Lipsey have no financial disclosures. Dr. Civitelli owns stock of Amgen, Merck & Co., and Eli-Lilly; he has also received consultant fees from Amgen and has been on the speaker bureau for Amgen and Novartis.

Dr. Müller has received the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation Award, CIHR Michael Smith New Investigator Salary Prize for Research in Schizophrenia, and an Early Researcher Award by the Ministry of Research and Innovation of Ontario.

Dr. Reynolds is supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers P60 MD000207; P30 MH090333; UL1RR024153, UL1TR000005; and the UPMC Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry. He received Medscape/WEB MD speaker honorarium. He is on the editorial review board of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Dr. Mulsant currently receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the US National Institute of Health (NIH), Bristol Myers Squibb (medication for a NIH-funded trial) and Pfizer (medication for a NIH-funded trial); within the past three years, he has also received travel support from Roche.

Dr. Lenze currently receives research support from Lundbeck and Roche, within the past three years has received research support from Johnson and Johnson.

Sponsor’s Role: This work was supported in part by grant P30 MH90333 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors gave final approval of the publication of this version of the study. Shea M.: manuscript preparation, literature search. Gebara M.: protocol development, data extraction, literature search, and manuscript preparation. LipseyK.: protocol development, literature search. Lenze E.: data extraction, manuscript preparation, protocol development. TietelbaumS.: data interpretation, manuscript revision. Civitelli R.: data interpretation, manuscript revision. Mulsant B.: data interpretation, manuscript revision. Reynolds C.: data interpretation, manuscript revision. Muller D.: data interpretation, manuscript revision.

Based on National Osteoporosis Foundation http://www.nof.org/aboutosteoporosis/bonebasics/whybone health estimates by 2025, three million osteoporosis-related fractures will cost $25.3 billion. 1/7 older adults are prescribed antidepressants; and SSRI use increases risk of fractures (RR=1.72). This number may be conservative, because it does not include costs other than direct health care cost.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2012;60:616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kvelde T, McVeigh C, Toson B, et al. Depressive symptomatology as a risk factor for falls in older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatric Soc. 2013;61:694–706. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabenda V, Nicolet D, Beaudart C, et al. Relationship between use of antidepressants and risk of fractures: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cizza G. Major depressive disorder is a risk factor for low bone mass, central obesity, and other medical conditions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:73–87. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/gcizza. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darowski A, Chambers SA, Chambers DJ. Antidepressants and falls in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:381–394. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200926050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson BI, Thommesen L, Stunes AK, et al. Serotonin and fluoxetine modulate bone cell function in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:139–151. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bliziotes MM, Eshleman AJ, Zhang XW, et al. Neurotransmitter action in osteoblasts: expression of a functional system for serotonin receptor activation and reuptake. Bone. 2001;29:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bliziotes MM, Eshleman AJ, Burt-Pichat B, et al. Serotonin transporter and receptor expression in osteocytic MLO-Y4 cells. Bone. 2006;39:1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westbroek I, van der Plas A, de Rooij KE, et al. Expression of serotonin receptors in bone. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28961–28968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnet N, Bernard P, Beaupied H, et al. Various effects of antidepressant drugs on bone microarchitectecture, mechanical properties and bone remodeling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Q, Bencaz AF, Hentz JG, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iaboni A, Flint AJ. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: A clinical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwan S, Hallberg P. SSRIs, bone mineral density, and risk of fractures--a review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill AB. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, et al. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diem SJ, Blackwell TL, Stone KL, et al. Depressive symptoms and rates of bone loss at the hip in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:824–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diem SJ, Blackwell TL, Stone KL, et al. Use of antidepressants and rates of hip bone loss in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1240–1245. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams LJ, Bjerkeset O, Langhammer A, et al. The association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and bone mineral density in the general population: The HUNT Study. J of Affect Disord. 2011;131:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweiger U, Deuschle M, Korner A, et al. Low lumbar bone mineral density in patients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1691–1693. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.11.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whooley MA, Kip KE, Cauley JA, et al. Depression, falls, and risk of fracture in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:484–490. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Paul I, et al. Depressive vulnerability is not an independent risk factor for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1999;33:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins J, Hirsch CH, Whitmer RA, et al. The association of bone mineral density and depression in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:732–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong SY, Lau EM, Lynn H, et al. Depression and bone mineral density: Is there a relationship in elderly Asian men? Results from Mr. Os (Hong Kong) Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:610–615. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman SL, Shen W, Minshall ME, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density and/or prevalent vertebral fracture: Results from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitson HE, Sanders L, Pieper CF, et al. Depressive symptomatology and fracture risk in community-dwelling older men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:585–592. doi: 10.1007/bf03324888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erez HB, Weller A, Vaisman N, et al. The relationship of depression, anxiety and stress with low bone mineral density in post-menopausal women. Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diem SJ, Harrison SL, Haney E, et al. Depressive symptoms and rates of bone loss at the hip in older men. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1975-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whooley MA, Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, et al. Depressive symptoms and bone mineral density in older men. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:88–92. doi: 10.1177/0891988704264537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spangler L, Scholes D, Brunner RL, et al. Depressive symptoms, bone loss, and fractures in postmenopausal women. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:567–574. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolton JM, Targownik LE, Leung S, et al. Risk of low bone mineral density associated with psychotropic medications and mental disorders in postmenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31:56–60. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182075587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ensrud KE, Blackwell T, Mangione CM, et al. Central nervous system active medications and risk for fractures in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:949–957. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cauley JA, Fullman RL, Stone KL, et al. Factors associated with the lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density in older men. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1525–1537. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haney EM, Chan BK, Diem SJ, et al. Association of low bone mineral density with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use by older men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards JB, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:188–194. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NIH consensus conference Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA. 1992;268:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diem SJ, Ruppert K, Cauley JA, et al. Rates of bone loss among women initiating antidepressant medication use in midlife. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4355–4363. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Mellon SH. Of sound mind and body: Depression, disease, and accelerated aging. Dialogues in Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:25–39. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/owolkowitz. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Hara R. Stress, aging, and mental health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:295–298. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216710.07227.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon NM, McNamara K, Chow CW, et al. A detailed examination of cytokine abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100–107. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aydin H, Mutlu N, Akbas NB. Treatment of a major depression episode suppresses markers of bone turnover in premenopausal women. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1316–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shea ML, Garfield LD, Teitelbaum SL, et al. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor therapy in late-life depression is associated with increased marker of bone resorption. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:1741–1749. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2170-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garfield LD, Muller DJ, Kennedy JL, et al. Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter and HTR1B receptor predicts reduced bone formation during serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in older adults. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013 Sep 30; doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.832380. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson JC, Delucchi KL, Schneider LS. Moderators of outcome in late-life depression: A patient-level meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:651–659. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Dew MA, Pollock BG, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1130–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:363–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenbroucke JP. When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials? Lancet. 2004;363:1728–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: New-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hicks JK, Swen JJ, Thorn CF, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes and dosing of tricyclic antidepressants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:402–408. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pagura J, Katz LY, Mojtabai R, et al. Antidepressant use in the absence of common mental disorders in the general population. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:494–501. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05776blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]