Abstract

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-related disorder characterized by hypertension (HTN) with unclear mechanism. Studies have shown endothelial dysfunction and increased endothelin-1 (ET-1) levels in hypertensive-pregnancy (HTN-Preg). ET-1 activates endothelin receptor type-A (ETAR) in vascular smooth muscle to induce vasoconstriction, but the role of vasodilator endothelial ETBR in the changes in blood pressure (BP) and vascular function in HTN-Preg is unclear. To test if downregulation of endothelial ETBR expression/activity plays a role in HTN-Preg, BP was measured in Norm-Preg rats and rat model of HTN-Preg produced by reduction of uteroplacental perfusion pressure (RUPP), and mesenteric microvessels were isolated for measuring diameter, [Ca2+]i, and ETAR and ETBR levels. BP, ET-1 and KCI-induced vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i were greater in RUPP than Norm-Preg rats. Endothelium-removal or microvessel treatment with ETBR antagonist BQ-788 enhanced ET-1 vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i in Norm-Preg, but not RUPP, suggesting reduced vasodilator ETBR in HTN-Preg. ET-1+ETAR antagonist BQ-123, and ETBR agonists sarafotoxin 6c (S6c) and IRL-1620 caused less vasorelaxation and nitrate/nitrite production in RUPP than Norm-Preg. The NOS inhibitor L-NAME reduced S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation in Norm-Preg but not RUPP, supporting that ETBR-mediated NO pathway is compromised in RUPP. RT-PCR, Western blots and immunohistochemistry revealed reduced endothelial ETBR expression in RUPP. Infusion of BQ-788 increased BP in Norm-Preg, and infusion of IRL-1620 reduced BP and ET-1 vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i and enhanced ETBR-mediated vasorelaxation in RUPP. Thus downregulation of microvascular vasodilator ETBR is a central mechanism in HTN-Preg, and increasing ETBR activity could be a target in managing preeclampsia.

Keywords: endothelin, calcium, nitric oxide, hypertension, preeclampsia

INTRODUCTION

Normal pregnancy (Norm-Preg) is associated with increased plasma volume and cardiac output, decreased vascular resistance, and slight or no change in blood pressure (BP).1 Preeclampsia is a major disorder affecting ~5-8% of pregnancies in the United States; 8 million pregnancies worldwide.2 Preeclampsia is manifested as maternal hypertension (HTN),3,4 and if untreated could lead to eclampsia with severe HTN and seizures. Preeclampsia may be associated with intrauterine growth restriction, and could lead to in-utero programming of cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic disorders and adult-onset HTN and diabetes.5 Although preeclampsia poses serious consequences to the health of mother and fetus, the mechanisms involved are unclear. Placental ischemia could be an initiating event4 leading to release of various bioactive factors in the maternal circulation including cytokines, anti-angiogenic factors, angiotensin receptor type-1 agonistic auto-antibody (AT1-AA), reactive oxygen species and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF).6-8 These circulating factors are thought to cause generalized endotheliosis in the peripheral, glomerular and cerebral vessels leading to some of the hallmarks of preeclampsia/eclampsia, namely HTN, proteinuria and seizures, respectively;9 however, the central endothelial cell target involved is unclear.

One of the major factors released by endothelium is endothelin-1 (ET-1). ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor in some forms of HTN including hypertensive pregnancy (HTNPreg).3,10 Also, plasma ET-1 levels are increased in preeclamptic women.3,11 Because of the difficulty to perform mechanistic studies in pregnant women, we and others have utilized animal models of HTN-Preg such as the rat model of placental ischemia produced by reduction of uteroplacental perfusion pressure (RUPP).6,8,12 The RUPP rat mimics some of the features of preeclampsia in women including HTN, endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular reactivity.3,4,12 RUPP rats also exhibit increased expression of preproET mRNA in renal medulla and cortex.13 ET-1 activates endothelin receptor type-A (ETAR) and type-B (ETBR). ETAR is mainly expressed in vascular smooth muscle (VSM) to induce vasoconstriction, whereas ETBR is predominately expressed in endothelial cells to induce the release of vasodilator substances,14,15 and also plays a role in ET-1 clearance.16 Although a role of ET-1 and its vasoconstrictor ETAR in modulation of cardiovascular-renal function during HTN-Preg has been suggested,3,17-19 the role of vasodilator endothelial ETBR during Norm-Preg and HTN-Preg, and the post-ETBR mediators involved are less clear.

We have recently shown that ET-1-induced vasoconstriction is reduced and that ETBR expression and ETBR-mediated vasodilation are enhanced in microvessels of Norm-Preg rats.20 The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that downregulation of endothelial ETBR is an important mechanism in HTN-Preg. We used mesenteric microvessels from RUPP and Norm-Preg rats to determine whether: 1) The increased BP in HTN-Preg reflects increased ET-1-induced constriction and decreased ETBR-mediated relaxation via the nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2) or endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) pathway, 2) HTN-Preg is associated with reduced endothelial ETBR expression/activity, 3) Downregulation of ETBR causes HTN-Preg, while enhancing ETBR activity reverses the increase in BP, promotes vasodilation, and reduces vasoconstriction in HTN-Preg. Because changes in [Ca2+]i are major determinants of VSM contraction/relaxation,20 particularly during Norm-Preg and HTN-Preg,21 the effects of ETBR modulation on microvascular [Ca2+]i were also measured.

METHODS

See details in online Methods Supplement.

Animals

Time-pregnant (day 13) Sprague-Dawley rats were either Sham-operated (Norm-Preg) or underwent surgical RUPP by placing a silver clip (0.203mm ID) on lower abdominal aorta and two clips (0.1mm ID) on uterine branches of the ovarian artery.8,12 To test the role of ETBR in HTN-Preg, other pregnant rats were infused with ETBR antagonist BQ-788 100μg/kg/day subcutaneously for 5-days using osmotic minipump. Also, some RUPP rats were infused with ETBR agonist IRL-1620 100μg/kg/day subcutaneously for 5-days. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the guidelines of Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Blood Pressure

On day 19 of gestation, BP was measured via a PE-50 carotid arterial catheter connected to a pressure transducer.

Tissue Preparation

Rats were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, the uterus was excised, and the litter size and individual pup weight were recorded. Third order mesenteric arteries (≤300μm OD) were dissected for measuring microvascular function, nitrate/nitrite production and Western blots. The thoracic aorta was used for measuring nitrate/nitrite production and RT-PCR.

Measurement of Microvessel Diameter and [Ca2+]i

Mesenteric microvessels were mounted between two glass cannulae (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT), pressurized under 60mmHg,20,21 and the vessel diameter was measured using automatic edge-detection system. For measurement of [Ca2+]i, microvessels were incubated in Krebs solution containing fura-2/AM (5μM) for 1 hr.20,21

Nitrate/Nitrite (NOx) Production

Endothelium-intact aortic and mesenteric artery segments were treated with acetylcholine (ACh, 10–6M), BQ-123+ET-1, sarafotoxin 6c (S6c) or IRL-1620 (10–7M) for 30min and the incubation solution was assayed for the stable end product of NO, NO2− using Griess reagent.12

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from thoracic aorta using RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), 1μg total RNA was used for reverse transcription to synthesize single-strand cDNA, and 2μl of cDNA dilution (1:5 for preproET, ETAR and ETBR, and 1:25 for α-actin) was applied to 20μl RT-PCR reaction. Gene expression was measured using quantitative RT-PCR system (Mx4000, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), published oligonucleotide primers for preproET, ETAR and ETBR (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA), and iQ-SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Relative mRNA expression was calculated by the comparative ΔδCT method, with α-actin as internal control.22

Western Blots

Microvessels were homogenized and proteins were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with polyclonal anti-ETAR (sc-33536) or anti-ETBR antibody (sc-33538) (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at 4°C overnight. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) and the intensity was normalized to β-actin.20

Immunohistochemisty

Transverse 6μm thick cryosections of mesenteric artery were labeled with polyclonal ETAR and ETBR antibodies (1:100). Vessel images were acquired on a Nikon microscope and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH). The total wall thickness, relative thickness of the intima, media and adventitia, and the amount of ETAR and ETBR in the whole vessel wall and in each layer were measured.

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were conducted on vessels from n=4-12 rats per group. Data were presented as means±SEM. Concentration-dependent responses were fitted to sigmoidal curves using the least squares method and pD2 (−log EC50) was calculated using Graphpad Prism 5.01. Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni's post hoc test for multiple comparisons or Student's t-test for comparison of two means. Differences were statistically significant when P<0.05.

RESULTS

On gestation day 19, the mean arterial BP was greater in RUPP (130±3mmHg) than Norm-Preg rats (92±6mmHg). RUPP rats showed smaller litter size (8±1 pups) and average pup weight (1.59±0.12g) than Norm-Preg (13±1 pups, average weight 2.24±0.25g).

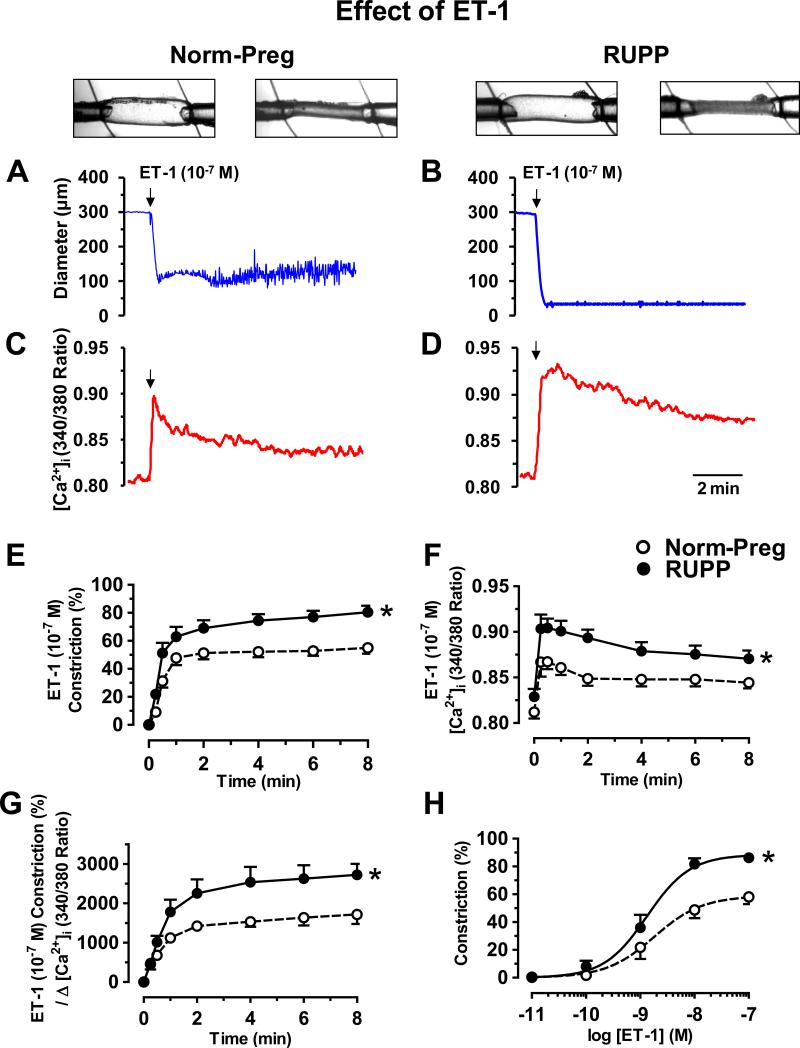

In mesenteric microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 1A) and RUPP rats (Fig. 1B), ET-1 (10−7M) caused maintained decrease in diameter, associated with an initial peak followed by smaller increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1C,D). Basal [Ca2+]i was not different in Norm-Preg (0.82±0.06) vs. RUPP (0.83±0.03), while ET-1-induced vasoconstriction (Fig.1E), [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1F), and Δ constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1G) were greater in RUPP than Norm-Preg. Also, ET-1-induced concentration-dependent constriction showed greater maximum constriction in RUPP (86.2±3.8%) than Norm-Preg (58.1±5.2%, P=0.004) with no difference in sensitivity (pD2 RUPP 8.88±0.10 vs. Norm-Preg 8.74±0.19, P=0.57) (Fig. 1H).

Fig. 1.

Effect of ET-1 on vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i. ET-1-induced changes in diameter (A,B) and [Ca2+]i (340/380 ratio) (C,D) were recorded simultaneously in microvessels from Norm-Preg (A,C) and RUPP rats (B,D). Cumulative ET-1-induced constriction (E), [Ca2+]i (F), constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i (G), and concentration-dependent constriction (H) were measured. Data represent means±SEM, n=5-12. *P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg.

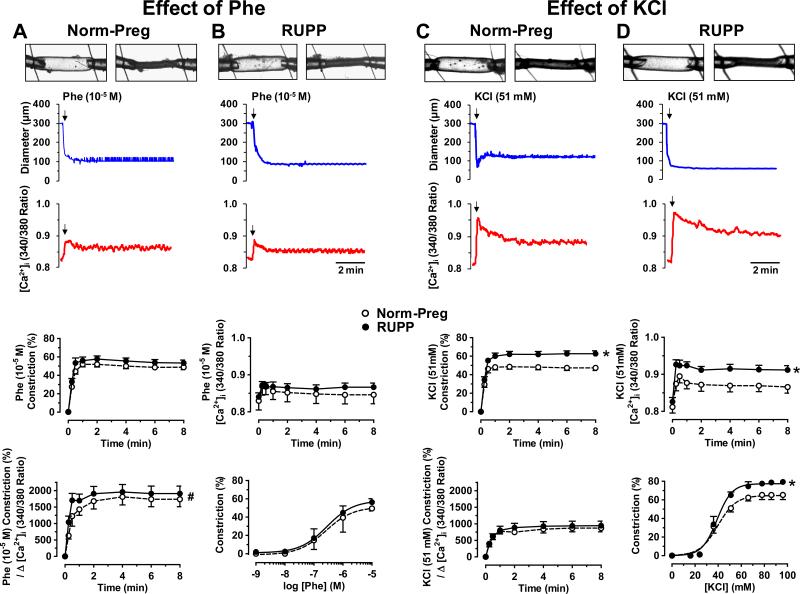

To test if the enhanced vasoconstriction is specific to ET-1 or involves mechanisms shared by other vasoconstrictors, the α-adrenergic receptor agonist phenylephrine (Phe) (10−5M) caused significant decrease in microvessel diameter and an initial spike followed by smaller increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2A,B). Cumulative data showed no differences in Phe-induced constriction, [Ca2+]i or Δ constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i in microvessels of Norm-Preg and RUPP (Fig. 2A,B). Also, Phe (10-9-10-5M) caused concentration-dependent constriction that was not different in vessels of RUPP (Emax=56.3±3.9%, pD2=6.55±0.30) and Norm-Preg (Emax=49.5±2.8%, pD2=6.59±0.33) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Phe and KCl on vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i in microvessels of Norm-Preg (A,C) and RUPP rats (B,D). Phe (10−5M) (A,B) and KCl (51mM) (C,D) induced changes in diameter and [Ca2+]i were recorded, and cumulative constriction, [Ca2+]i and constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i were measured. Phe (10−9-10−5M) and KCl (16-96mM) concentration-constriction curves were also constructed. Data represent means±SEM, n=10-12. *P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg. #P<0.05, Phe vs. KCl.

High KCI is known to cause membrane depolarization and to stimulate Ca2+ entry. In microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 2C) and RUPP rats (Fig. 2D), KCI (51mM) caused maintained decrease in diameter and an initial spike followed by maintained [Ca2+]i. KCl-induced constriction and [Ca2+]i were greater in RUPP than Norm-Preg, but Δ constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i was not different in Norm-Preg and RUPP (Fig. 2). Also, KCI (16 to 96 mM) caused concentration-dependent vasoconstriction that was greater in microvessels of RUPP (Emax=79.3±5.0%) than Norm-Preg (Emax=65.3±4.9%) (Fig. 2).

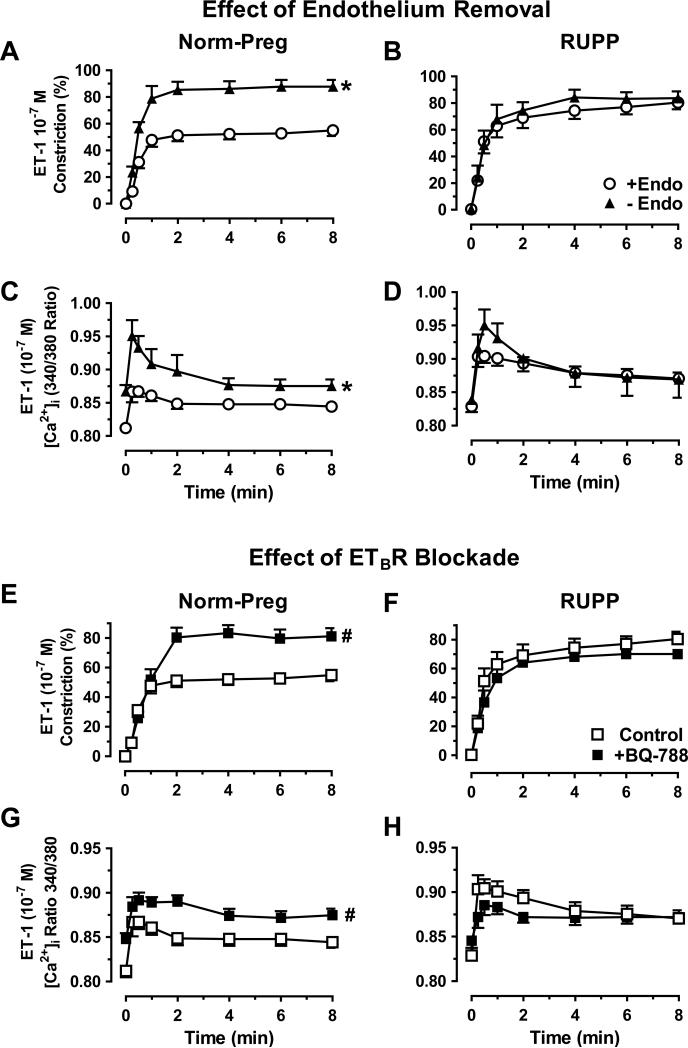

To test the role of endothelium, ET-1-induced constriction and [Ca2+]i were enhanced in endothelium-denuded vs. intact microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 3A,C) but not RUPP (Fig. 3B,D), suggesting that endothelial function is already compromised in RUPP. Phe- and KCI-induced constriction and [Ca2+]i were not different in endothelium-denuded vs. intact vessels of Norm-Preg or RUPP (data not shown), supporting that the effects of endothelium removal are specific to an ET-1 stimulated receptor/signaling pathway. ETBR antagonist BQ-788 (10−6M) enhanced ET-1 constriction and [Ca2+]i in microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 3E,G) but not RUPP (Fig. 3F,H), suggesting an intact vasodilator ETBR activity in Norm-Preg rats, that is reduced in RUPP.

Fig. 3.

Effect of endothelium-removal and ETBR blockade on ET-1 response. ET-1-induced constriction and [Ca2+]i were compared in endothelium-denuded (-Endo) and intact (+Endo) microvessels of Norm-Preg (A,C) and RUPP rats (B,D), and in nontreated or ETBR antagonist BQ-788 (10−6M) pretreated microvessels from Norm-Preg (E,G) and RUPP rats (F,H). Data represent means±SEM, n=5-12. *P<0.05, -Endo vs. +Endo. #P<0.05, with vs. without BQ-788.

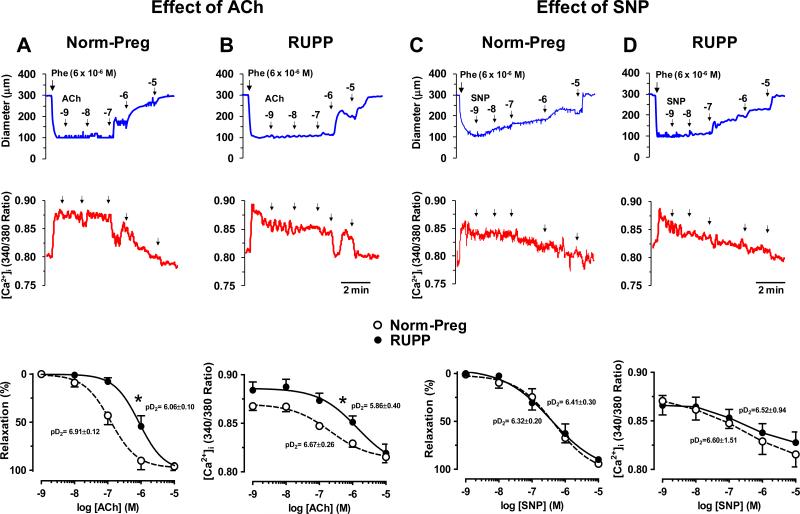

To further test the role of endothelium, in microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 4A) and RUPP (Fig. 4B) preconstricted with Phe, ACh caused concentration-dependent increases in diameter and simultaneous decreases in [Ca2+]i. ACh was less potent in inducing relaxation in RUPP (pD2=6.06±0.10) than Norm-Preg (pD2=6.91±0.12), with no differences in maximal relaxation (Fig. 4). Also, ACh was less potent in decreasing [Ca2+]i in RUPP (pD2=5.86±0.40) than Norm-Preg (pD2=6.67±0.26), with no difference in maximal effect on [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4). To test the responsiveness of VSM to vasodilators, the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) caused concentration-dependent increases in diameter and decreases in [Ca2+]I, and was equally potent in inducing relaxation in vessels of Norm-Preg (pD2=6.32±0.20) (Fig. 4C) and RUPP rats (pD2=6.41±0.30) (Fig. 4D) with no difference in maximal relaxation or underlying [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of acetylcholine (ACh) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) on relaxation and [Ca2+]i in microvessels of Norm-Preg (A,C) and RUPP rats (B,D). Microvessels were preconstricted with Phe (6×10−6M) and ACh and SNP induced changes in diameter and [Ca2+]i, cumulative concentration-relaxation and [Ca2+]i curves, and pD2 were measured. Data represent means±SEM, n=10-12. *P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg.

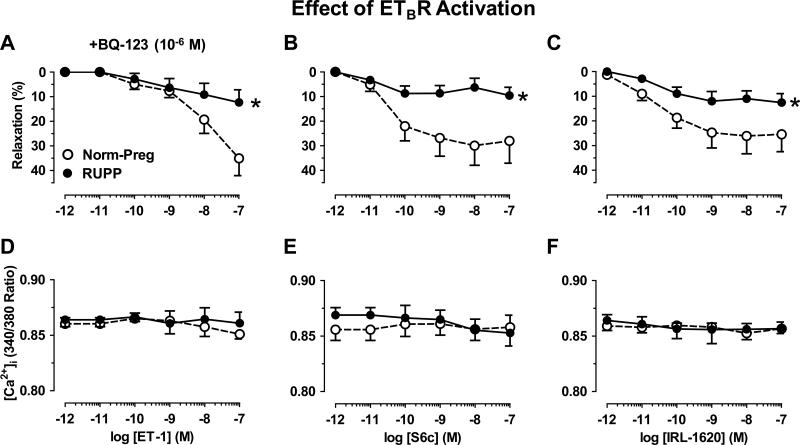

In microvessels preconstricted with Phe, ET-1 in the presence of ETAR antagonist BQ-123 (10-6M) (Fig. 5A), or selective ETBR agonists S6c (Fig. 5B) and IRL-1620 (Fig. 5C) caused concentration-dependent relaxation that was less in RUPP than Norm-Preg, with no difference in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5D,E,F).

Fig. 5.

Effect of ETBR activation on microvascular relaxation in Norm-Preg and RUPP rats. Microvessels were preconstricted with Phe (6×10−6M), then treated with ET-1 (10–12-10–7M) plus ETAR antagonist BQ-123 (10−6M) (A,D), or with ETBR agonists sarafotoxin 6c (S6c) (B,E) and IRL-1620 (C,F) and % relaxation of Phe constriction (A,B,C) and underlying [Ca2+]i (D,E,F) were compared in Norm-Preg and RUPP rats. Data represent means±SEM, n=10-12. *P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg.

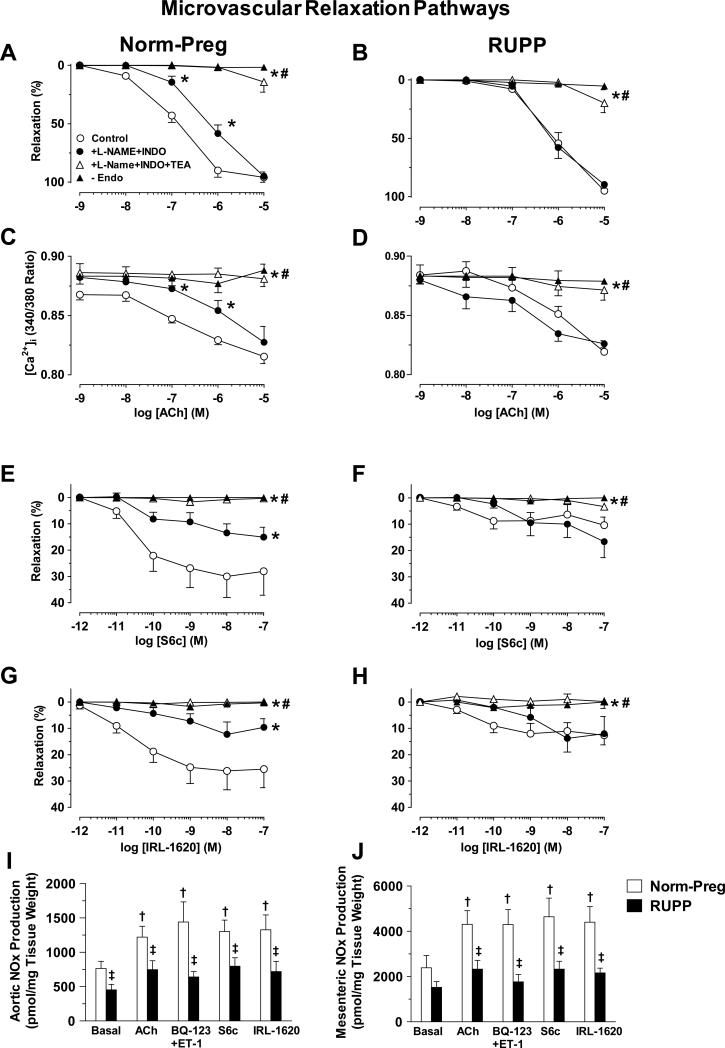

To investigate the vascular mediators released during microvascular relaxation, the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (3×10-4M) plus cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (INDO, 10-6M) caused a shift to the right in ACh concentration-relaxation curve in Norm-Preg (pD2 control=6.91±0.12, +L-NAME+INDO=6.13±0.15, Fig. 6A), but not RUPP (pD2 control=6.06±0.10, +L-NAME+INDO=6.19±0.11, Fig. 6B), suggesting that an NO-mediated vasodilator component is active in Norm-Preg but reduced in RUPP. L-NAME+INDO also reduced ACh-induced changes in [Ca2+]i in Norm-Preg (Fig. 6C) but not RUPP (Fig. 6D). The L-NAME+INDO-resistant component of ACh-induced relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i was similarly abolished by the K+ channel blocker tetraethylammonium (TEA, 30mM) or in endothelium-denuded microvessels of both Norm-Preg (Fig. 6A,C) and RUPP (Fig. 6B,D), suggesting similar contribution of EDHF.

Fig. 6.

Role of NO, PGI2 and EDHF in microvascular relaxation. Microvessels of Norm-Preg (A,C) and RUPP rats (B,D) were preconstricted with Phe (6×10−6 M), and ACh (10-9-10−5M) induced relaxation and underlying [Ca2+]i in absence or presence of L-NAME (3×10−4M)+indomethacin (INDO, 10−6M) and TEA (30mM), and in endothelium-denuded vessels (-Endo) were recorded. Concentration-relaxation curves to S6c and IRL-1620 were also constructed in microvessels of Norm-Preg (E,G) and RUPP rats (F,H). Basal, ACh (10−6M), BQ-123+ET-1, S6c and IRL-160 (10−7M) stimulated nitrate/nitrite (NOx) production were also measured in aortic (I) and mesenteric arterial segments (J). Data represent means±SEM, n=4-12. *P<0.05, vs. control measurements in absence of blockers. #P<0.05, vs. measurements in presence of L-NAME+INDO. †P<0.05, vs. basal measurements. ‡P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg.

To test the vascular factors involved in ETBR-mediated relaxation, L-NAME+INDO reduced S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation in microvessels of Norm-Preg (Fig. 6E,G), but not RUPP (Fig. 6F,H). Additional treatment with TEA or endothelium removal abolished S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation in Norm-Preg (Fig. 6E,G) and RUPP (Fig. 6F,H). To further test the role of NO, we first measured nitrate/nitrite production in aortic segments as previously described.7,12 Basal, ACh (10-6M), BQ-123+ET-1, S6c and IRL-1620 (10-7M)-induced nitrate/nitrite production was reduced in aorta of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 6I). Using a similar protocol, nitrate/nitrite production was reduced in mesenteric arterial segments of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 6J).

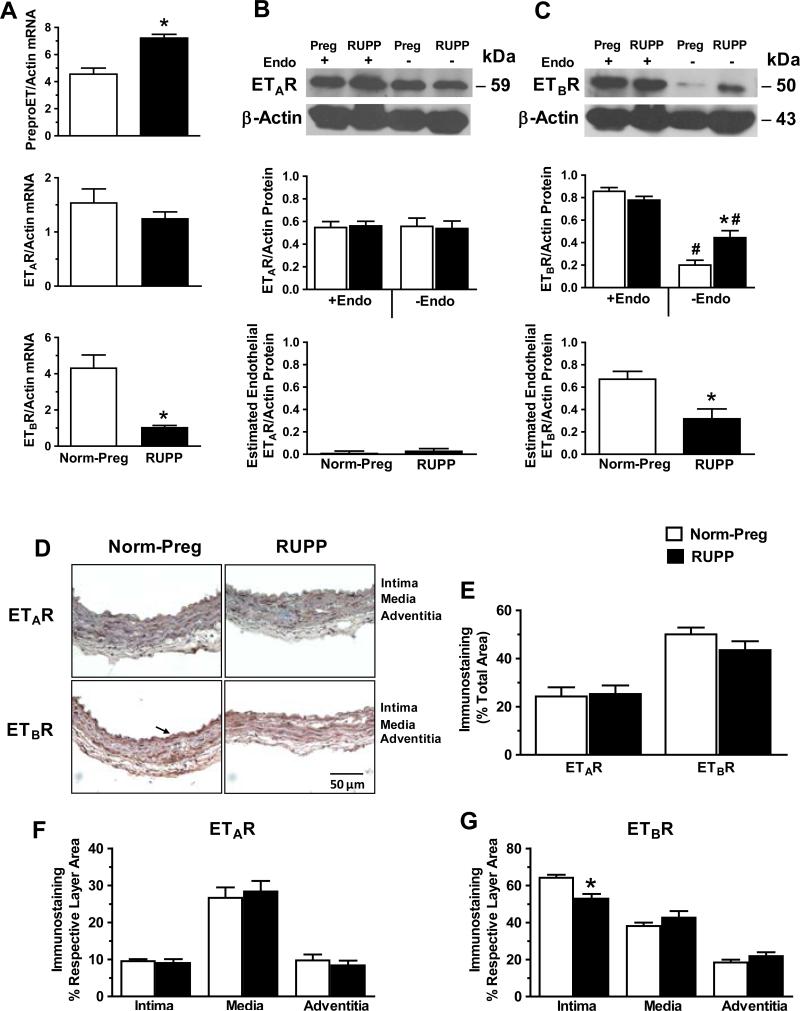

RT-PCR revealed that preproET mRNA expression was greater, ETAR mRNA was not different, while ETBR mRNA was reduced in aorta of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 7A). Western blots revealed that ETAR protein level was not significantly different in endothelium-intact or -denuded microvessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg, or between endothelium-denuded and intact microvessels of either RUPP or Norm-Preg (Fig. 7B). ETBR level was insignificantly reduced (P=0.12) in endothelium-intact microvessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg, and significantly reduced in endothelium-denuded vs. intact microvessels of both Norm-Preg and RUPP (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, ETBR level was greater in endothelium-denuded microvessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 7C). To estimate the amount of endothelial ETAR and ETBR, the protein level in endothelium-denuded vessels was subtracted from the protein level in endothelium-intact vessels. While the estimated endothelial ETAR was not different (Fig. 7B), the estimated endothelial ETBR was less in RUPP than Norm-Preg (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Expression, protein amount and localization of ETAR and ETBR in vessels of Norm-Preg and RUPP rats. RT-PCR was performed on aortic tissue homogenate and mRNA expression of preproET, ETAR and ETBR was measured (A). Western blots were performed to compare protein levels of ETAR and ETBR in endothelium-intact vs. -denuded mesenteric vessels of Norm-Preg and RUPP rats (B,C, top). To estimate endothelial ETAR and ETBR, the protein level in endothelium-denuded vessels was subtracted from that in endothelium-intact vessels (B,C, bottom). The distribution of ETAR and ETBR immunostaining was measured in vessel sections (D). Arrow indicates prominent staining in the intima. The total number of pixels in the tissue section was first defined, then the number of brown spots (pixels) was counted and presented as % of total area (E). The number of pixels in the intima, media and adventitia was also defined, then ETAR (F) and ETBR brown staining (G) was counted and presented as % of the respective layer area. Data represent means±SEM, n=4-5. *P<0.05, RUPP vs. Norm-Preg. #P<0.05, -Endo vs. +Endo.

Immunohistochemistry revealed that total ETAR immunostaining was not different and total ETBR was insignificantly reduced (P=0.10) in mesenteric vessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 7D,E). ETAR staining was not different in intima, media or adventitia of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 7F). ETBR staining was significantly reduced in intima and endothelium, insignificantly increased in media, and not different in adventitia of mesenteric vessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg (Fig. 7G).

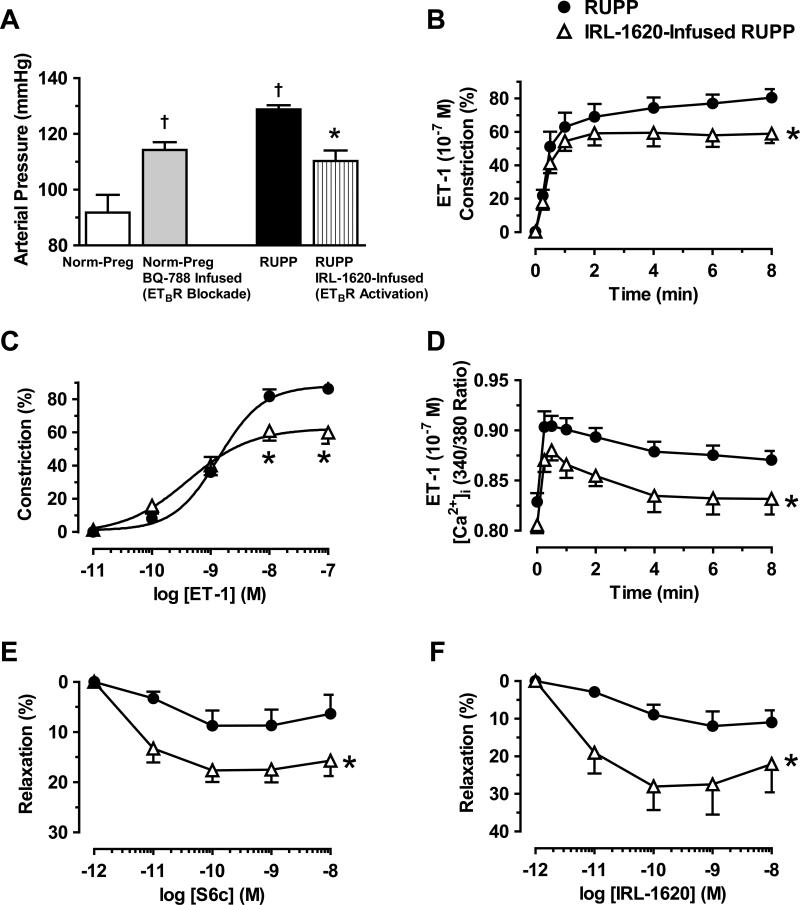

Infusion of ETBR antagonist BQ-788 for 5-days in Norm-Preg rats resulted in increased BP compared with control non-treated Norm-Preg (Fig. 8A). Infusion of RUPP rats with IRL-1620 for 5-days reduced BP compared with non-treated RUPP (Fig. 8A). Also, ET-1 (10-7M) induced constriction and [Ca2+]i (Fig. 8B,D) and ET-1 (10-11-10-7M)-induced concentration-dependent constriction (Fig. 8C) were reduced in microvessels isolated from IRL-1620-infused vs. non-treated RUPP. The relaxation response to ex vivo application of ETBR agonists S6c (Fig. 8E) and IRL-1620 (Fig. 8F) was also enhanced in microvessels of IRL-1620-infused vs. non-treated RUPP.

Fig. 8.

In vivo effects of ETBR antagonists and agonists. Norm-Preg rats were infused with ETBR antagonist BQ-788, and RUPP rats were infused with ETBR agonist IRL-1620. On day 19 of pregnancy, BP was measured (A), microvessels were isolated, and ET-1 (10−7M)-induced constriction (B) and [Ca2+]i (D), ET-1-induced concentration-dependent constriction (C), and S6c- (E) and IRL-1620-induced concentration-dependent relaxation (F) were recorded. Data represent means±SEM, n=5-12.†P<0.05, vs. Norm-Preg. *P<0.05, RUPP infused with IRL-1620 vs. RUPP.

DISCUSSION

Preeclampsia is manifested as HTN and often intrauterine growth restriction.2,23 Although the mechanisms of preeclampsia are unclear, placental ischemia is thought to be an initiating event. Studies in animal models of HTN-Preg such as the RUPP rat model of placental ischemia-induced HTN have shown many of the features of preeclampsia.4,6,8,12 Consistent with these reports, the present study showed that RUPP in late pregnant rats was associated with increased BP, and decreased litter size and average pup weight. Studies have related the main characteristics of preeclampsia and HTN-Preg to generalized endotheliosis,9 decreased release of vasodilator substances such as NO and EDHF, and/or increased release of vasoconstrictors such as ET-1. Plasma ET-1 levels are increased in preeclamptic women.3,11 Also, RUPP rats exhibit increased renal tissue expression of preproET.13 Chronic hypoxia during pregnancy in rats is associated with preeclampsia-like manifestations and increased ET-1 plasma levels and preproET mRNA and ETAR protein in kidneys and placenta.24 Also, serum from RUPP rats increases ET-1 production by cultured endothelial cells.17 Consistent with these reports, we found an increase in aortic preproET mRNA expression in RUPP vs. Norm-Preg rats, supporting a role for enhanced ET-1 system in placental ischemia-induced HTN.

To test the microvascular effects of ET-1 in HTN-Preg, ET-1-induced constriction was enhanced in RUPP vs. Norm-Preg. These data are different from reports that ET-1 produces similar vascular contraction in Norm-Preg and RUPP rats.19,21 The differences may be related to regional differences along the arterial tree25 (first order mesenteric arteries19 vs. the present third order mesenteric microvessels) or the method of measuring vascular function (wire myography19 vs. the present pressurized microvessels). Importantly, we observed enhanced ET-1 constriction in endothelium-intact but not -denuded vessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg rats. While we measured endothelium-dependent relaxation in our pressurized microvessels, other studies did not measure endothelial function,19,21 and the endothelium integrity could be compromised during microdissection or passage of wire in the vessel in the wire myography studies.

To test if the enhanced contraction is specific to ET-1, the α-adrenergic receptor agonist Phe caused increases in constriction and [Ca2+]i that were not different in microvessels of Norm-Preg and RUPP. The lack of difference in Phe contraction is in accordance with other reports in mesenteric arteries,21,26 and suggests that the enhanced vasoconstriction in RUPP rats is specific to ET-1-activated receptor and signaling mechanisms and not generalized to receptor-mediated vasoconstrictor stimuli.

The enhanced ET-1 vasoconstriction in RUPP vs. Norm-Preg rats was associated with greater initial peak [Ca2+]i, likely due to Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores, and greater maintained [Ca2+]i, likely due to Ca2+ influx.27,28 High KCI causes membrane depolarization and stimulates Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs). The greater KCl-induced constriction and [Ca2+]i in RUPP vs. Norm-Preg rats support a role of increased microvascular Ca2+ influx through VGCCs in HTN-Preg, although ET-1 induced Ca2+ influx may also involve receptor- and store-operated Ca2+ channels.27

We have used the ratio of vasoconstriction/Δ [Ca2+]i as a measure of Ca2+ sensitivity of VSM contractile proteins.20 KCI vasoconstriction/Δ [Ca2+]i was similar in RUPP and Norm-Preg rats, supporting that KCI-induced contraction is Ca2+-dependent. While maximal Phe-induced constriction was similar to that of KCl, [Ca2+]i was smaller and the constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i was greater with Phe than KCl (Fig. 2), suggesting activation of additional mechanisms that increase the myofilament force sensitivity to [Ca2+]i. Likewise, ET-1 induced constriction/Δ [Ca2+]i was greater in microvessels of RUPP than Norm-Preg, suggesting that the enhanced ET-1-induced vasoconstriction in RUPP may not be exclusively due to VSM [Ca2+]i but could also involve Ca2+ sensitization pathways such as protein kinase-C (PKC), Rho-kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK).29

Although ET-1 is known for its vasoconstrictor effects, intravenous injection of ET-1 causes transient hypotension followed by delayed increase in BP,30,31 which has been attributed to its two receptor subtypes, ETAR and ETBR.32,33 ETAR is largely localized in VSM causing vasoconstriction, increased [Ca2+]i, and activation of other pathways of VSM contraction and growth.34 In contrast, ETBR is located predominately in the endothelium and mediates vasodilation.15,35 Studies have shown that treatment of RUPP rats with an ETAR antagonist decreases BP, and suggested a role for ETAR in HTN-Preg.13,18,24,36 However, the decreased BP in RUPP rats treated with ETAR antagonist can also be explained by the possibility that most ET-1 would be directed towards endothelial ETBR to promote vasodilation, and thus made it important to examine the role of vascular ETBR in normotensive and HTN-Preg.

We have recently shown that upregulation of endothelial ETBR may be responsible for the blunted ET-1 vasoconstriction and enhanced ETBR-mediated vasodilation in Norm-Preg rats.20 The present microvascular function studies suggest that the enhanced ET-1 constriction in HTN-Preg produced by RUPP could be due to downregulation of vasodilator endothelial ETBR because: 1) Endothelium removal enhanced ET-1 vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i in Norm-Preg but not RUPP, suggesting that an endothelium-dependent pathway that reduces ET-1 contraction during Norm-Preg is compromised in RUPP rats. 2) Endothelium removal did not enhance Phe contraction in microvessels of Norm-Preg or RUPP rats, supporting specific changes in ET-1 receptor/signaling in the endothelium. 3) ETBR antagonist BQ-788 enhanced ET-1 constriction and [Ca2+]i in microvessels of Norm-Preg but not RUPP, suggesting active vasodilator ETBR in Norm-Preg but not HTN-Preg rats. 4) ETBR-mediated microvascular relaxation in response to ET-1 in presence of ETAR antagonist BQ-123, or the ETBR agonists S6c and IRL-1620 was less in RUPP than Norm-Preg, supporting reduced endothelial ETBR vasodilator activity in HTN-Preg. Our biochemical and histochemical studies support that ETBR is downregulated in HTN-Preg because: 1) RT-PCR showed reduced ETBR mRNA expression in aorta of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg, 2) Western blots revealed that the estimated endothelial ETBR was less in microvessels of RUPP than Norm-Preg. 3) Immunohistochemistry demonstrated prominent localization of ETBR in the mesenteric vessel intima of Norm-Preg that was reduced in RUPP rats. The observations that ETAR mRNA, protein level and immunohistochemical distribution were not different in RUPP and Norm-Preg rats, support that the enhanced ET-1 contraction in microvessels of RUPP rats is not due to primary increase in VSM ETAR, and is more likely secondary to downregulation of endothelial ETBR vasodilator activity.

The endothelium releases NO, PGI2 and EDHF. NO diffuses into VSM where it increases cGMP which causes vascular relaxation by decreasing VSM [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ sensitivity of contractile proteins. In agreement with studies on mesenteric arteries26,37 and aorta of RUPP rats,12 ACh was less potent in inducing relaxation and decreasing [Ca2+]i in microvessels of RUPP than Norm-Preg rats. Similar to ACh, the decreased ETBR-mediated relaxation in RUPP rats is partly due to decreased endothelium-derived NO and the NO-cGMP relaxation pathway because: 1) Endothelium removal abolished ACh-, S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation. 2) Blocking NO synthesis by L-NAME partly reduced ACh-induced relaxation and changes in [Ca2+]i as well as S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation in Norm-Preg, but not RUPP. ETBR agonists-induced microvascular relaxation was not associated with decrease in [Ca2+]i suggesting that ETBR-mediated activation of NO-cGMP may function by decreasing Ca2+-sensitivity of VSM contractile proteins. 3) Basal, ACh-, S6cand IRL-1620-induced nitrate/nitrite production were less in aorta and mesenteric arteries of RUPP than Norm-Preg. 4) SNP-induced relaxation and [Ca2+]i were not different in microvessels of RUPP and Norm-Preg rats supporting that the impaired ACh- and ETBR agonists-induced relaxation was not due to decreased sensitivity of VSM to NO-cGMP. 5) While EDHF is an important vasodilator in resistance arteries38 and may explain the L-NAME+INDO resistant component of ACh-, S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation, its blockade with TEA caused similar inhibition of ACh- and ETBR-agonists-induced relaxation in RUPP and Norm-Preg rats supporting an intact EDHF and equally active EDHF-dependent ETBR-mediated pathway in both groups. The reduced ETBR-mediated NO but not EDHF pathway in RUPP rats could be related to possible uncoupling of ETBR from NO but not EDHF, or the presence of sub-population of ETBR or other ET-1 receptor subtype(s) with different post-receptor NO or EDHF signaling through receptor heterodimerization or crosstalk mechanisms.

Our in vivo findings also support a role of ETBR downregulation in HTN-Preg. Infusion of ETBR antagonist BQ-788 in pregnant rats caused an increase in BP, likely because during ETBR blockade most of endogenous ET-1 will bind to ETAR and cause vasoconstriction. ETBR is also involved in ET-1 clearance, and ETBR blockade is predicted to allow more endogenous ET-1 to activate ETA R and increase vasoconstriction and BP.35 A study by Madsen and coworkers39 showed that infusion of ETBR antagonist A-192621 caused maintained increases in BP in virgin rats, and dose-dependently increased maternal BP, although these increases were not sustained in pregnant rats. While we observed comparable elevation in maternal BP, the cause of the differences in maintained BP is unclear and could be partly related to the ETBR antagonist used, i.e. A-19261 vs. BQ-788. Also, BP regulation involves not only vascular but also renal, neuronal and hormonal mechanisms, and increased BP via the vascular mechanism could be compensated by other control mechanisms. For instance, ETBR in renal medulla may regulate salt and water excretion, plasma volume and BP.33 Also, changes in vascular reactivity in vivo may be compensated by cardiac baroreceptor reflexes and mask any vascular effects on BP.25 We should note that Madsen study did not measure vascular function, while we measured the “direct” ex vivo effects of ETBR agonists and antagonists on microvessels and demonstrated a role of decreased endothelial ETBR in the decreased vasodilation in HTNPreg. Furthermore, we showed that infusion of ETBR agonist IRL-1620 reduced BP in RUPP rats and that ET-1 constriction and [Ca2+]i were reduced, and S6c- and IRL-1620-induced relaxation were enhanced in microvessels of RUPP rats infused with IRL-1620, supporting that increasing ETBR activity improves ETBR-mediated vasodilation, reduces vasoconstriction and decreases BP in HTN-Preg. Whether the effects of in vivo modulation of ETBR using ETBR agonists and antagonists on BP and microvascular activity reflect changes in the sensitivity, mRNA expression, protein levels and/or vascular tissue localization of ETBR should be examined in future studies.

An important question is what causes downregulation of endothelial ETBR in HTN-Preg. Preeclampsia and HTN-Preg are associated with increased vasoactive factors such as cytokines, anti-angiogenic factors and AT1-AA.6-8,36 Serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)is increased in RUPP rats,36 and infusion of pregnant rats with TNFα is associated with decreased vascular relaxation, increased contraction, HTN-Preg,7 and increased preproET mRNA expression in placenta, aorta and kidneys.36 Also, in preeclampsia there is an imbalance between the angiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor, and the anti-angiogenic factor soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1)9. RUPP rats also show increased serum sFlt-1,8 and infusion of sFlt-1 in pregnant rats results in increased BP, decreased plasma VEGF,40 and increased tissue levels of ET-1.41 In preeclampsia, there is also an increase in AT1-AA which could activate angiotensin type-1 receptor in VSM leading to enhanced vasoconstriction and HTN-Preg,6,42 and infusion of AT1-AA in pregnant rats causes increases in renal and placental ET-1.6 Future studies should test if the vasoactive factors released during HTN-Preg affect the expression/activity of endothelial ETBR. ETBR has been identified not only in endothelium, but may also be expressed in VSM, where it could promote vasoconstriction.15,22,43 Our Western blots showed greater ETBR levels in endothelium-denuded microvessels and immunohistochemistry showed insignificant increase (P=0.10) in ETBR in tunica media of mesenteric vessels of RUPP vs. Norm-Preg rats, suggesting a role of VSM ETBR in HTNPreg, and the functionality and potential vasoconstrictive effects of these receptors need to be further evaluated in endothelium-denuded vessels and isolated VSM cells.

Perspectives

Endothelial ETBR expression/activity is reduced in pregnant rats with RUPP, and may explain the increased BP and ET-1 vasoconstriction, and reduced ETBR-mediated relaxation in placental ischemia-induced HTN. While the data should be interpreted in a more circumspect fashion since there are forms of HTN-Preg and preeclampsia that may not be adequately represented by the RUPP model, the results suggest that ETBR could be an important target in HTN-Preg, and upregulation of endothelial ETBR, using pharmacological agonists or genetic manipulation, may represent a novel approach in managing preeclampsia.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is New?

The present study provides new information on the role of microvascular endothelial ETBR in placental ischemia-induced HTN, and first evidence that its downregulation is a major causative mechanism in HTN-Preg.

The results highlight the importance of targeting vascular endothelial ETBR in treatment of HTN-Preg, and could have an impact on future therapeutic strategies of preeclampsia.

What Is Relevant?

HTN-Preg and preeclampsia are major disorders affecting ~5-8% of pregnancies in the United States, but the underlying vascular mechanisms are unclear.

Reduction in uteroplacental perfusion pressure (RUPP) could be an initiating event, but the central vascular target is unclear.

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a potent vasoconstrictor in some forms of HTN acting via ETAR in VSM, but could also affect ETBR in the endothelium.

Although the role of ETAR in vasoconstriction has been studied, the role of vasodilator endothelial ETBR, particularly during HTN-Preg, is poorly understood.

Summary

Downregulation of microvascular endothelial vasodilator ETBR is a critical causative mechanism in HTN-Preg.

Increasing ETBR activity could be a target in managing HTN-Preg and preeclampsia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Sridhar Rangan and Matthew Finn for assistance in data analysis.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Supported by grants HL-65998, HL-98724, HL-111775, HD-60702. M.Q.M. is a recipient of AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship. W.L was a visiting scholar from Tongji Hospital, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and a recipient of a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thornburg KL, Jacobson SL, Giraud GD, Morton MJ. Hemodynamic changes in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(00)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R, Ayoubi JM. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:467–474. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S20181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George EM, Palei AC, Granger JP. Endothelin as a final common pathway in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia: therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:157–162. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328350094b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalil RA, Granger JP. Vascular mechanisms of increased arterial pressure in preeclampsia: lessons from animal models. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R29–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00762.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander BT. Fetal programming of hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1–R10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00417.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray LF, Murphy SR, Roberts L, Glover P, Wallukat G, Wenzel K, Cockrell K, Martin JN, Jr., Ryan MJ, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension. 2009;54:905–909. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis JR, Giardina JB, Green GM, Alexander BT, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Reduced endothelial NO-cGMP vascular relaxation pathway during TNF-alpha-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R390–399. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00270.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert JS, Babcock SA, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reduced uterine perfusion in pregnant rats is associated with increased soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression. Hypertension. 2007;50:1142–1147. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiffrin EL. Vascular endothelin in hypertension. Vascul Pharmacol. 2005;43:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma D, Singh A, Trivedi SS, Bhattacharjee J. Role of endothelin and inflammatory cytokines in pre-eclampsia - A pilot North Indian study. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:428–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crews JK, Herrington JN, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Decreased endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation during reduction of uterine perfusion pressure in pregnant rat. Hypertension. 2000;35:367–372. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander BT, Rinewalt AN, Cockrell KL, Massey MB, Bennett WA, Granger JP. Endothelin type a receptor blockade attenuates the hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion pressure. Hypertension. 2001;37:485–489. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakashima M, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelin-1 and -3 cause endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in the rat mesenteric artery. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H2137–2141. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.6.H2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tirapelli CR, Casolari DA, Yogi A, Montezano AC, Tostes RC, Legros E, D'Orleans-Juste P, de Oliveira AM. Functional characterization and expression of endothelin receptors in rat carotid artery: involvement of nitric oxide, a vasodilator prostanoid and the opening of K+ channels in ETB-induced relaxation. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:903–912. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelland NF, Kuc RE, McLean DL, Azfer A, Bagnall AJ, Gray GA, Gulliver-Sloan FH, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP, Kotelevtsev YV, Webb DJ. Endothelial cell-specific ETB receptor knockout: autoradiographic and histological characterisation and crucial role in the clearance of endothelin-1. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:644–651. doi: 10.1139/Y10-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts L, LaMarca BB, Fournier L, Bain J, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Enhanced endothelin synthesis by endothelial cells exposed to sera from pregnant rats with decreased uterine perfusion. Hypertension. 2006;47:615–618. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000197950.42301.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam Tam KB, George E, Cockrell K, Arany M, Speed J, Martin JN, Jr., Lamarca B, Granger JP. Endothelin type A receptor antagonist attenuates placental ischemia-induced hypertension and uterine vascular resistance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:330, e331–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdalvand A, Morton JS, Bourque SL, Quon AL, Davidge ST. Matrix metalloproteinase enhances big-endothelin-1 constriction in mesenteric vessels of pregnant rats with reduced uterine blood flow. Hypertension. 2013;61:488–493. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzuca MQ, Dang Y, Khalil RA. Enhanced endothelin receptor type B-mediated vasodilation and underlying [Ca(2+) ]i in mesenteric microvessels of pregnant rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1335–1351. doi: 10.1111/bph.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen W, Khalil RA. Differential [Ca2+]i signaling of vasoconstriction in mesenteric microvessels of normal and reduced uterine perfusion pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1962–1972. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90523.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou M, Dang Y, Mazzuca MQ, Basile R, Khalil RA. Adaptive regulation of endothelin receptor type-A and type-B in vascular smooth muscle cells during pregnancy in rats. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:489–501. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou J, Xiao D, Hu Y, Wang Z, Paradis A, Mata-Greenwood E, Zhang L. Gestational hypoxia induces preeclampsia-like symptoms via heightened endothelin-1 signaling in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2013;62:599–607. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Angelo G, Osol G. Regional variation in resistance artery diameter responses to alpha-adrenergic stimulation during pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H78–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez RJ, Debrah J, Novak J. Increased myogenic responses of resistancesized mesenteric arteries after reduced uterine perfusion pressure in pregnant rats. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30:45–57. doi: 10.3109/10641950903322923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neylon CB. Vascular biology of endothelin signal transduction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:149–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroeder AC, Imig JD, LeBlanc EA, Pham BT, Pollock DM, Inscho EW. Endothelin-mediated calcium signaling in preglomerular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2000;35:280–286. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cain AE, Tanner DM, Khalil RA. Endothelin-1--induced enhancement of coronary smooth muscle contraction via MAPK-dependent and MAPK-independent [Ca(2+)](i) sensitization pathways. Hypertension. 2002;39:543–549. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts-Thomson P, McRitchie RJ, Chalmers JP. Endothelin-1 causes a biphasic response in systemic vasculature and increases myocardial contractility in conscious rabbits. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;24:100–107. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199407000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matz RL, Van Overloop B, Gairard A. Hypotensive effect of endothelin-1 in nitric oxide-deprived, hypertensive pregnant rats. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:585–591. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gariepy CE, Ohuchi T, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Salt-sensitive hypertension in endothelin-B receptor-deficient rats. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:925–933. doi: 10.1172/JCI8609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohan DE, Rossi NF, Inscho EW, Pollock DM. Regulation of blood pressure and salt homeostasis by endothelin. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Vascular biology of endothelin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32(Suppl 3):S2–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzuca MQ, Khalil RA. Vascular endothelin receptor type B: structure, function and dysregulation in vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2005;46:82–86. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000169152.59854.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh SK, English FA, Johns EJ, Kenny LC. Plasma-mediated vascular dysfunction in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure model of preeclampsia: a microvascular characterization. Hypertension. 2009;54:345–351. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.132191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM. EDHF: an update. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;117:139–155. doi: 10.1042/CS20090096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madsen KM, Neerhof MG, Wessale JL, Thaete LG. Influence of ET(B) receptor antagonism on pregnancy outcome in rats. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2001;8:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(01)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bridges JP, Gilbert JS, Colson D, Gilbert SA, Dukes MP, Ryan MJ, Granger JP. Oxidative stress contributes to soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 induced vascular dysfunction in pregnant rats. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:564–568. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy SR, LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2010;55:394–398. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, Lindschau C, Horstkamp B, Jupner A, Baur E, Nissen E, Vetter K, Neichel D, Dudenhausen JW, Haller H, Luft FC. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:945–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Touyz RM, Deng LY, Schiffrin EL. Endothelin subtype B receptor-mediated calcium and contractile responses in small arteries of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1995;26:1041–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.