Abstract

In April, 2014, the City of Richmond, California, became one of the first and only municipalities in the USA to adopt a Health in All Policies (HiAP) ordinance and strategy. HiAP is increasingly recognized as an important method for ensuring policy making outside the health sector addresses the determinants of health and social equity. A central challenge facing HiAP is how to integrate community knowledge and health equity considerations into the agendas of policymakers who have not previously considered health as their responsibility or view the value of such an approach. In Richmond, the HiAP strategy has an explicit focus on equity and guides city services from budgeting to built and social environment programs. We describe the evolution of Richmond’s HiAP strategy and its content. We highlight how this urban HiAP was the result of the coproduction of science policy. Coproduction includes participatory processes where different public stakeholders, scientific experts, and government sector leaders come together to jointly generate policy goals, health equity metrics, and policy drafting and implementation strategies. We conclude with some insights for how city governments might consider HiAP as an approach to achieve “targeted universalism,” or the idea that general population health goals can be achieved by targeting actions and improvements for specific vulnerable groups and places.

Keywords: Health in all policies, Urban governance, Health equity, Healthy cities, City planning

Introduction

The City of Richmond, California, is one of the first in the USA to adopt a Health in All Policies (HiAP) strategy and ordinance with the objective of integrating health equity into all city services and policymaking. The ordinance makes HiAP law, and the strategy is the implementing guide developed jointly by the city, community stakeholders, and public health officials. HiAP is an approach to decision making that recognizes most public policies have the potential to influence health and health equity, either positively or negatively, but policy makers outside of the health sector may not be routinely considering the health consequences of their choices and thereby missing opportunities to advance health and prevent disease and unnecessary suffering.1

The impetus for HiAP emerged, in part, from the World Health Organization’s Declaration of Alma-Ata in 19782 and reflects numerous international calls for policy action to address the social determinants of health.3 The European Union endorsed HiAP in 2006, and the governments of Finland, Norway, Sweden, UK, Canada, South Australia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Iran, and Brazil have all adopted some form of HiAP within governmental practice.4 The Dutch government actively supports municipalities to draft and implement HiAP strategies, but very few have managed to complete and implement these strategies, noting the difficulty in getting government actors and institutions outside the health sector to consider health impacts in their work.5,6 While the USA has not formally adopted HiAP at the federal level, many national and state health promotion activities reflect the core tenets of HiAP.7 One of the most clearly defined HiAP programs at the state-scale in the USA is in California whose Strategic Growth Council8 formally adopted HiAP in May 2012 and integrated the practice into a newly created Office of Health Equity within the California Health and Safety Code in 2013.9 Washington, DC10 passed the Sustainable DC Transformation Order in 2013, creating a HiAP Task Force, and the Chicago Department of Public Health created the Healthy Chicago Interagency Council to integrate health across all city departments.11 However, we are not aware of any city in the USA other than Richmond, CA, that has adopted their own HiAP strategy and ordinance.

In this paper, we describe and analyze the emergence and development of HiAP in Richmond, California, over the past 4 years. We reconstruct events and practices utilizing participant observation, over 25 interviews with leaders from local government agencies and community-based organizations, minutes from tens of public meetings, internal staff emails, confidential project grant reports, and publically available documents (such as meeting reports and presentations found at Richmondhealth.org). Using these data, we reveal the conceptual frames, practical strategies, and evaluation evidence that contributed to an urban Health in All Policies practice explicitly focused on addressing health equity. More specifically, we document how health equity frames, namely, cumulative toxic stress and structural racism, were selected and used to shape the HiAP strategy and selection of quantitative indicators to measure progress.

Coproducing Health Equity in all Policies

Health equity is “the absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically,” and health inequities refer to health differences that are socially produced, systematic across the population, and unfair.12 A major social justice challenge for cities is the increase in health inequities—or the differences in social opportunities and related health outcomes between the wealthy and their lower-income, often immigrant, and people of color neighbors. Urban health inequities are the result of the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age and the governmental and other social support systems they can access.13 An opportunity for city governments and non-governmental organizations is that many of the resources needed to be healthy and reduce chronic health inequities—such as economic development incentives, physical infrastructure, and social services—are influenced by institutions at the local or municipal scale.

HiAP is now understood as an important practice for governments to address the root causes of health inequities by encouraging inter-sectoral action for health promotion, which entails actions outside the medical and public health sectors that influence population health outcomes.14 In this paper, we use inter-sectoral to mean action across typical, and frequently fragmented, municipal government functions (i.e., land use, housing, transport, economic development, environmental protection, etc.) and scales of governance (i.e., formal government, non-governmental organizations, academics, scientists, etc.). A recent review of published assessments of inter-sectoral actions to address health equity suggests that such actions show promise in creating supportive environments and can act to enhance access to services for marginalized populations.15

HiAP is an approach to public decision making that moves beyond ad hoc or short-term health promotion programs but rather integrates health and health equity into newly established processes of governmental decision making.16 As Rudolph et al. suggest, HiAP is often used as shorthand for simultaneously integrating health, equity, and sustainability into all public policymaking.17 In addition, as Frieler et al. note, “HiAP requires a mechanism for moving beyond the detection of health equity problems (e.g., mere health equity impact assessment) to foster remedial action involving an inter-sectoral response.”18:1069 Thus, HiAP is neither a strictly technical exercise nor only politics, but rather ought to be the result of the coproduction of knowledge and action strategies for health equity.

As outlined above, a central aim of HiAP is to transform the content, processes, and outcomes of public decision making so all are more attentive to population health. We view these aims as healthy urban governance, where governance is not just the formal rules of government but the struggles and conflicts between formal institutions and organizations and informal norms and practices. Urban governance includes a complex mix of different contexts, actors, arenas, and issues, where struggles over power can be manifested in public discourses or tacit day-to-day routines.19 A key aspect of healthy urban governance is democratic participation, or the ways different policy stakeholders from residents to non-governmental organizations, to government agencies, and to scientific and technical experts, are included or excluded in public decision-making processes. These processes are at the heart of the idea of coproduction, or the “process through which inputs used to produce a good or service is contributed by individuals who are not ‘in’ the same organization”20:1073 Coproduction avoids the notion that non-experts have a deficit of knowledge about an issue but rather that lay people, scientists, and government can together generate the most socially just and technically sound public policy solutions.21,22

Health Inequities in Richmond, California

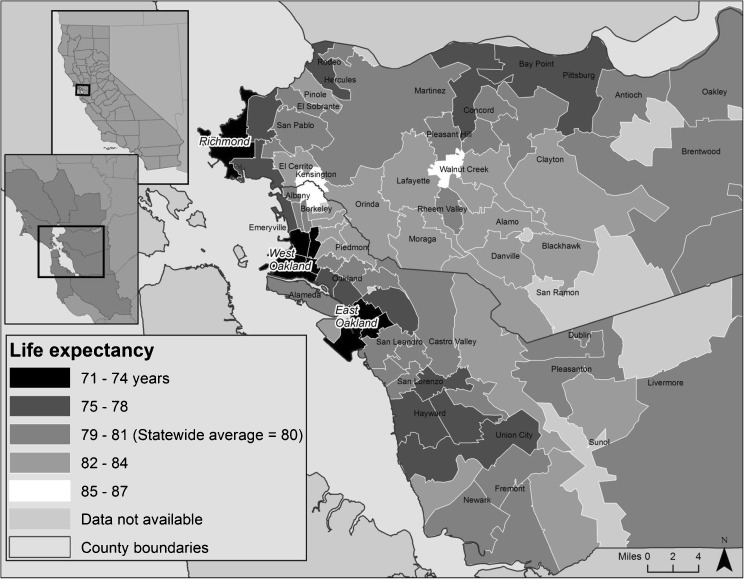

Located in California’s San Francisco Bay Area, Richmond is the largest city located in western Contra Costa County with a population of over 103,000 residents (Fig. 1). Richmond is also one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the San Francisco Bay Area, with over 26 % African-American, 40 % Latino, 31 % white, and 14 % Asian-Pacific Islanders. Richmond is also home to a large port and an oil refinery operated by Chevron Corporation, which dominates the city’s industrial landscape and is the region’s largest source of toxic and greenhouse gas pollutants.23 In 2010, nearly 19 % of Richmond residents were unemployed, 38 % of children were living in poverty, and 57 % of households paid more than 30 % of their income for housing.24 Health outcomes in Richmond reflect these social inequalities.

FIG. 1.

Richmond, California life expectancy, 2010.

According to a 2010 Contra Costa County Health Services report, 22 % of African-American children were hospitalized for asthma compared with less than 9 % of white children; 32 % of adults age 20–44 were obese, compared with 21 % of similar Californians; and over 28 % of residents report their health as fair or poor, compared with only 16 % of similar Californians.25 The Contra Costa Times reported in 2010 that the ZIP code in central Richmond (94603) had a life expectancy of 71.2 years (the California state average is 78.4 years), while a few miles away in another ZIP code over the Richmond Hills, life expectancy was over 87 years (Fig. 1).26

An Institutional Commitment to Urban Health

In part a response to chronic health inequities, community-based organizations demanded that the City of Richmond take more aggressive action when formulating the update to the Richmond General Plan. Starting in 2007, the city and community stakeholders began drafting California’s first Community Health and Wellness Element (CHWE) as part of Richmond’s General Plan Update. The General Plan is a legally required analysis and 30-year projection of policy and development decisions for a city. This was the first time that a local government in California developed a health-specific focus to its land-use development plan, and a Technical Advisory Committee was established to help draft the CHWE that included both community activists and public health scientists.27

Emerging out of the initial pilot phase of the Community Health and Wellness Element (CHWE) was a strategy to implement its recommended actions through a new cross-government and community alliance called the Richmond Health Equity Partnership (RHEP).28 The RHEP was an extension of the CHWE technical advisory committee and pilot implementation initiatives but included additional departments from both city and county governments, as well as representatives from the local school district and a host of non-profit and community-based organizations. With financial support from The California Endowment (TCE), the RHEP was charged with developing an integrated health equity strategy for Richmond. The group decided that one of its first tasks would be drafting a HiAP strategy and ordinance with an explicit focus on health equity. All this work represented a new institutional approach to public health in Richmond focused on prevention and policy and that the entire workings of city government, not just the health department, could address health inequities.29

Cumulative Toxic Stressors and Structural Racism

A first stage in coproducing the HiAP strategy in Richmond was to work with residents to develop a framework for identifying the key drivers of health inequities and the ways local policy might promote greater health equity. Fourteen community workshops were held between March 2012 and November 2013, with residents, members of various community-based organizations, and city and school district representatives. During these workshops, participants worked together to define health and health equity and identify the specific influences on the health of Richmond’s residents living in different neighborhoods and from different population groups (i.e., youth, elderly, Latinos, African-Americans, etc.). State and county collected health data in the form of outcome statistics were also shared in these meetings, but the workshops focused on getting residents to identify the opportunities and barriers they faced to lead healthy lives.

Priority concerns from community stakeholders that emerged during these workshops included environmental pollution, neighborhood violence, unemployment, unsafe physical infrastructure, and affordable access to quality goods and services, such as food, childcare, and health care. Some community activists noted that they were also involved in the drafting of a screening tool by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) called “EnviroScreen,” that was to become the nation’s first comprehensive methodology for identifying multiple environmental, social, and health vulnerabilities at the community scale (http://oehha.ca.gov/ej/ces2.html), and that a similar framework could be applied in Richmond.

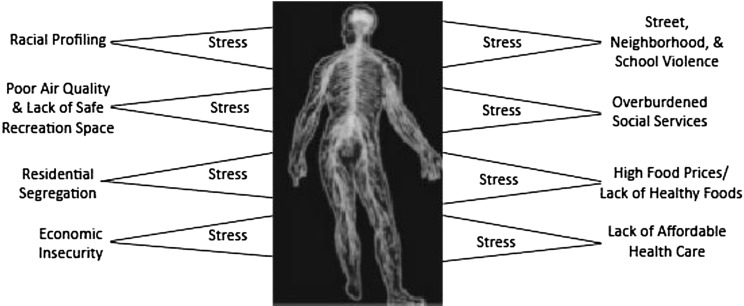

What emerged from the workshops was a consensus that there were multiple and simultaneous influences in the daily lives of Richmond residents that acted as both barriers and opportunities to be healthy. Building on the idea of cumulative environmental stressors raised by the CalEnviroScreen methodology, public health professionals participating in the workshops shared what was called the “cumulative toxic stressors model.” The cumulative toxic stressors model is based on medical and public health evidence suggesting that chronic social and environmental stressors, across the life-course, are biologically embodied and damage the immune system in multiple ways.30,31 For example, Richmond residents regularly described how, in the same day, they might experience or fear violence, environmental pollution, being evicted from housing, not being able to pay health care bills, discrimination at work or in school, challenges accessing public services, and immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) intimidation. These and other experiences contribute to the multiple toxic stressors typical in Richmond and suggested that the HiAP strategy could not focus on one disease, risk, or behavior at a time but needed an integrated approach (Fig. 2). Discussions revolved around the cumulative toxic stressors model, and consensus was reached that this framework most closely reflected residents’ lived experiences in Richmond and was adopted by stakeholders to inform the content of the new HiAP strategy.

FIG. 2.

Cumulative toxic stressors model used in Richmond’s health equity in all policies strategy.

Also emerging from the workshops and health equity discussions was that one of the underlying causes of the multiple stressors experienced in Richmond was structural racism. By structural racism we meant that seemingly neutral policies and practices can function in racist ways by disempowering communities of color and perpetuating unequal historic conditions. Powell notes that a structural racism lens helps us analyze:

how housing, education, employment, transportation, health care, and other systems interact to produce racialized outcomes. Such a model allows us to move beyond a narrow merit-based, individualized understanding of society to show how all groups are interconnected and how structures shape life chances. At the level of cultural understanding, the structural model shows how the structures we create, inhabit, and maintain in turn recreate us by shaping identity and imparting social meaning. Chief among the processes in a structural model that connect institutions to identity formation is the relationship between racial identity and geography…the racialization of space.32:793

Thus, the charge for drafting Richmond’s HiAP was to generate practical strategies the city could adopt that helped to dismantle structural racism and privilege and mitigate the multiple toxic stressors faced by residents.

In addition to the community workshops, 16 similar workshops were held with different city departments and leaders. The cumulative exposures and toxic stress models were also used in the meetings with city department staff and combined with available health data. Workshop discussions revolved around how the work of every city department could influence the health of residents. For example, the director of the City’s Office of Neighborhood Safety noted that “what we do in reducing street-level conflicts and gun violence is a public health intervention.” Another city staffer from the Public Works Department stated: “now I see that when we repair streets and city infrastructure, we are also addressing health and safety.” As the workshops proceeded, the city manager suggested that all city staff see themselves as “community clinicians”—a term introduced by the public health facilitator of the workshops—and this idea helped city leaders and staff reconceptualize their work as health promotion and prevention. City leaders and staff were also asked how their department might reduce some of the “toxic stressors” identified by residents. Results from these workshops were summarized and shared back with members of the RHEP HiAP drafting subcommittee, which was comprised of city and county government staff, CBO representatives, and public health professionals.

Drafting an Urban Health Equity in All Policy Strategy

The drafting committee began by researching and sharing health equity and HiAP models from around the world. Based on this review and emerging outcomes from the workshops, staff from the city manager’s office and city council generated the first drafts of the HiAP strategy. A single text was created and edited during and in between monthly subcommittee meetings. Two presentations of the draft HiAP strategy and proposed ordinance were made to the Richmond City Council, and on January 29, 2013, the council voted unanimously to authorize the City Managers’ Office to move forward with a final strategy and ordinance. All working drafts and meeting materials were shared on the city’s Website.33

An initial set of 12 HiAP intervention areas were narrowed to six during ongoing workshops with community-based organizations and city staff. The narrowing of intervention areas was done primarily to ensure the HiAP was consistent with the categories and policy areas in the City’s General Plan and Budget, thus ensuring consistency across related documents and enhancing the possibility of using similar performance measures. The final HiAP intervention areas focused on how city policy, management, and service decisions could begin to reduce the multiple toxic stressors in Richmond and included the following: (1) Governance and Leadership, (2) Economic Development and Education, (3) Full Service and Safe Communities, (4) Neighborhood Built Environments, (5) Environmental Health and Justice, and (6) Quality and Accessible Health Homes and Social Services. Each intervention area included three to six short-term (1–2 years) and medium-term (5 year) policy and programmatic strategies targeting one or more “toxic stressor” in Richmond.

The Governance and Leadership intervention area focused on institutionalizing health equity awareness and practices within all functions of city management including the city’s budget and committing to transparent HiAP review processes, training, data sharing, and annual reporting. The Economic Development and Education section targeted city investment in the following: existing workforce development initiatives, traditionally underrepresented people of color and women-owned local businesses, neighborhood-based childcare, new health service job training programs, and a partnership with the school district to implement a full-service community school program. The Full Service and Safe Communities intervention area focused on neighborhood-scale programmatic interventions that are known to reduce “toxic stressors” and support healthy choices, including promoting healthy food store development through land-use zoning and enhancing the city’s financial investments in and commitment to restorative justice, community-based violence reduction, and prisoner reentry programs. The Residential and Built Environment intervention area focused on directing city resources toward revitalizing foreclosed and substandard housing, expanding lead paint abatement, improving street lighting, developing a homelessness prevention and emergency shelter program, and engineering “road diets” that make streets safer by narrowing vehicles lanes and widening pedestrian and bicycle zones. The Environmental Health and Justice section included investing in climate change adaptation in vulnerable neighborhoods, a comprehensive asthma reduction program, community-based air monitoring around the Chevron oil refinery, rerouting truck routes away from residential areas, and hazardous waste and brownfield site remediation. The Quality and Accessible Health Homes and Social Services intervention area emphasized how the city could increase access to health care due to opportunities available with implementation of the Affordable Care Act and enrollment in other safety net programs, such as CalFresh, Head Start, Medicaid/Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and expand a place-based community health workers (CHWs) program that offered both employment opportunities and health promotion services to low-income residents and people of color.

Health Equity Indicators

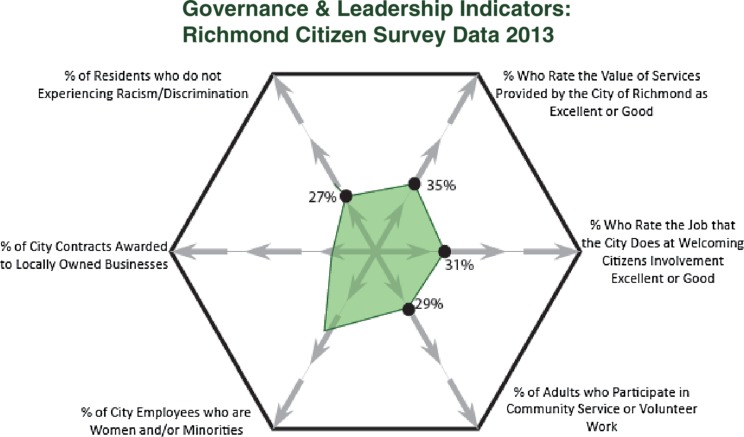

Included with each intervention area were six, city-specific quantitative measures in the form of a “health equity diamond” that captured current conditions and highlighted some of the indicators the HiAP strategy would use to track progress. For example, the Governance and Leadership section included responses from the city’s biannual community survey that the drafting committee and residents agreed reflected performance and leadership of government, including the following: percentage of residents rating the value of services provided by the city as excellent or good; percentage of residents that rate the job that the city does at involving citizens as excellent or good (this was also reported by race/ethnicity); percentage of adults who volunteer on local board, council, or organizations that address community problems; percentage of city employees who are women and/or minorities; percentage of city contracts awarded to locally owned businesses; and percentage of residents reporting few or no experiences with racism and/or discrimination in last year (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Governance and leadership HiAP intervention area: relational diamond indicators.

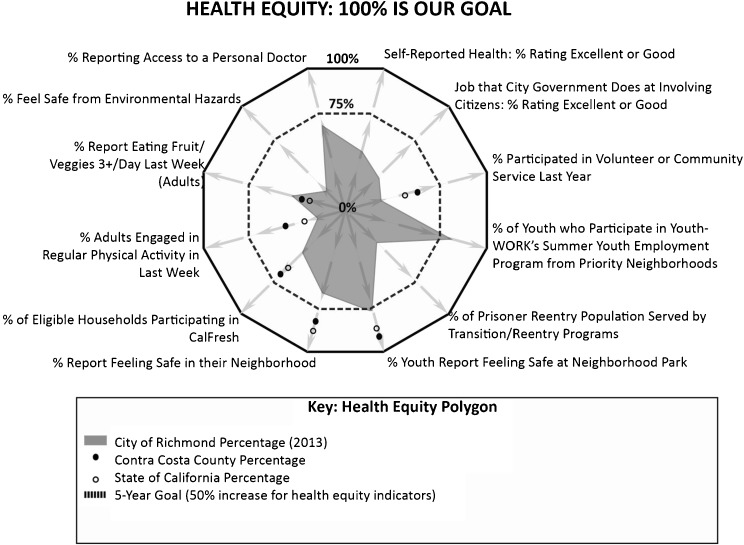

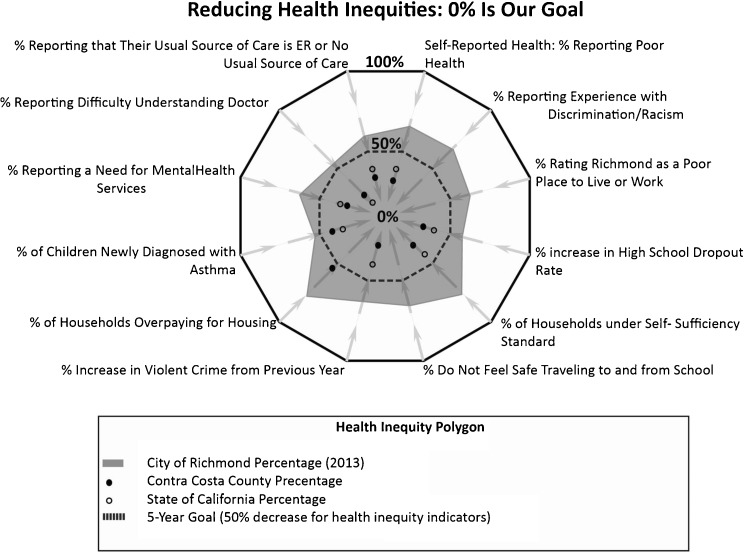

Indicators and measures of equity played a significant role in defining the direction of the entire HiAP strategy. In both community and city staff workshops, there was a strong desire for the HiAP to make health equity goals as explicit as possible. Residents were concerned with holding city departments accountable, and city staff were concerned with having concrete and measurable goals in their work. The HiAP drafting committee utilized a range of existing city and State of California data to generate “relational healthy city diamonds” that acted as the set of measures for promoting greater health equity (Fig. 4) and reducing health inequities (Fig. 5). Participants agreed to use existing publically available data, which consisted primarily of the California Health Interview Survey and Richmond’s Community Survey, and this allowed the HiAP strategy to compare current conditions in Richmond to those in the surrounding county and the entire State of California.

FIG. 4.

Health equity diamond: Richmond HiAP strategy.

FIG. 5.

Health inequities diamond: Richmond HiAP strategy.

The Healthy City Diamonds aimed to visually communicate, like the cumulative stressors framework, that a combination of measures in relation to one another characterized both health inequities and health equity in Richmond. For each diamond, the goal was either to reduce the shaded area (i.e., health inequities toward 0 %) or increase the percentage of respondents and the corresponding shaded area (i.e., health equity moving toward 100 %).

Impacts of the Urban Health Equity in All Policies Process

The HiAP ordinance and accompanying implementing strategy were enacted into law in April 2014 by the Richmond City Council. While it is too early to report on the impacts of implementation, the drafting and development process itself has led to important healthy urban governance impacts. Perhaps the most crucial impact of the HiAP process is that Richmond’s approach to governance has been transformed to prioritize health equity within almost all its planning, fiscal, and service decisions. For example, the Richmond City Manager’s Office is already implementing HiAP trainings for staff in the ways multiple government decisions can help eliminate barriers that impact health equity as a result of historical injustices such as racism and privilege and thereby reduce some key “toxic stressors.” This is a crucial first step in using a structural racism lens to promote health equity, since the HiAP strategy focuses on addressing inter-institutional dynamics and decisions—not just individual racism or formally race-neutral practices that often have the effect of disadvantaging certain racial or ethnic groups.

We are not suggesting that the HiAP drafting processes alone have caused structural changes to city governance but rather that the process has been a major contributor to some significant health equity-promoting actions and shifts in practice. For instance, the mayor and city council have proposed using the power of eminent domain to support families under threat of losing their homes to foreclosure and to redevelop abandoned neighborhoods.34 In September 2012, the Richmond Police Chief challenged the County Sheriff’s proposal for expanding the West County Detention Facility in Richmond. The Chief argued instead that the $19 million should be used for improved community services and supporting parolees. According to Adam Kruggel, executive director of Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization (CCISCO), a group organizing for violence reduction and city programs to support people not prisons, the decision by the City of Richmond was “a great example of elected officials really, truly listening to the voice of the community and responding.”35 For the first time, the city challenged Chevron for its failure to pay its fair share of taxes and a settlement in 2013 will result in an additional $60 million per year to the city.36 All of these actions included community and city government stakeholders that were and continue to be active participants in the HiAP process.

Also in 2013, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley, selected Richmond over 20 other possible locations for its second campus, emphasizing that Richmond was a city on the rise and that these institutions wanted to be a part of this renaissance.37 Now called the Richmond Bay Campus, this project will likely be the largest development project in the San Francisco Bay area and is projected to add at least 10,000 new jobs and a host of other amenities. A recent San Francisco Bay Area newspaper also described the changes in Richmond as a “renaissance:”

A new spirit in city government has helped transform industry, the quality of life in the city, and Richmond’s grim reputation. The city has undergone a facelift, citizens are attending community meetings and events in unprecedented numbers, and new businesses—many of them green—are bringing economic opportunities back to town. While other cities are desperately contending with debilitating budget deficits and struggling to maintain public safety and other basic services, Richmond has produced balanced budgets and enjoys a full complement of police officers. The combined efforts of city departments and community members have resulted in meaningful reductions in violent crime. And the city has completed numerous civic and neighborhood revitalization projects that have given Richmond a new air of vitality and community health.38

As a result of the health equity work surrounding the drafting of the HiAP strategy, the city has secured over $10 million in external funds that is being used to make playgrounds and streets safer, expand community violence reduction programs, increase youth employment opportunities, and reduce energy bills of lower-income residents through free installation of photovoltaic solar panels.

Conclusions: HiAP as Targeted Universalism

We have shown here that municipal government can develop their own HiAP strategy with an explicit focus on health equity. A model of the key drivers of health inequities proved to be extremely important in identifying the structural influences behind health inequities and helped shape the content of the HiAP. Integrating a structural racism lens emphasized the importance of addressing the multiple and interacting governmental decisions as a whole system that over time can produce often unintended racialized effects on health. This systems and structural approach within the HiAP was intended to complement ongoing anti-discrimination programs focused on the individual and/or a single institution. Participatory workshops with a range of stakeholders, from community to city staff, were also crucial for generating policy solutions and transforming the governance relationships between the city and its residents. Quantitative data in the form of health equity indicators help ground the process in tangible measures and give city government departments performance goals.

We have not suggested here that HiAP alone can contribute to healthy urban governance, but rather it is an important process in coproducing new science policy for healthier and more equitable cities. Further, we suggest that HiAP is important for urban health equity because it can help advance a “targeted universalism” approach, or the combination of public policies that deliver extra benefits to disadvantaged groups within the context of a universal or more general approach to population health.39 In other words, targeted universalism establishes general health equity goals for the city, while simultaneously targeting populations and places to help specific, currently vulnerable groups and neighborhoods get healthier. This is what we have aimed to do with our urban HiAP strategy in Richmond, and while more work needs to be done to evaluate our progress, we are on our way toward integrating health equity into all city services.

Funding

The work described in the paper was funded by The California Endowment, Grant No. 20112093.

References

- 1.Ollila E. Health in All Policies: from rhetoric to action. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:11. doi: 10.1177/1403494810379895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Declaration of Alma-Ata. Alma-Ata, USSR, 1978. Available at, http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed 11 Mar 2014.

- 3.Kickbusch I, McCann W, Sherbon T. Adelaide revisited: from healthy public policy to health in all policies. Health Promot Int. 2008;23:1–4. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kickbusch I. Health in All Policies: setting the scene. Public Health Bull S Australia. 2008;5:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steenbakkersa M, Jansena M, Maarseb H, de Vriesc N. Challenging Health in All Policies, an action research study in Dutch municipalities. Health Policy. 2012;105(2–3):288–95. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storm I, Harting J, Stronks K, Schuit AJ. Measuring stages of health in all policies on a local level: the applicability of a maturity model. Health Policy. 2014;114(2–3):183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gase LN, Pennotti R, Smith KD. Health in All Policies: taking stock of emerging practices to incorporate health in decision making in the United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19:529–40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182980c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.California Health in All Policies Task Force. Health in All Policies Task Force Implementation Plan: Health and Health Equity in State Guidance. 2012. Available at http://sgc.ca.gov/hiap/docs/publications/Endorsed__HiAP_Implementation_plan_Health_and_Health_Equity_in_State_Guidance.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2014.

- 9.California Health And Safety Code Section 131000–131020. 2013. Available at, http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/displaycode?section=hsc&group=130001131000&file=131000-131020. Accessed 17 Jan 2014.

- 10.District of Columbia. Mayor Gray announces multiple initiatives to continue implementation of sustainable DC initiative. Available at http://mayor.dc.gov/release/mayor-gray-announces-multiple-initiatives-continue-implementation-sustainable-dc-initiative. Accessed 25 Mar 2014.

- 11.Healthy Chicago, what we do. Available at http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/cdph/provdrs/healthychicago.html. Accessed 20 Mar 2014.

- 12.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. Concepts and Principles for tackling social inequities in health: leveling up part 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. WHOLIS E89383. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf. Accessed 11 Nov 2013.

- 13.CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. Available at www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.Html. Accessed 1 Dec 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, Freiler A, Bobbili S, Bayoumi A, et al. Getting started with Health in All Policies: a resource pack. Centre for Research on Inner City Health (CRICH), Ontario, Canada, 2011. Available at http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/crich/reports/hiap/. Accessed 11 Nov 2013.

- 15.Shankardass K, Solar O, Murphy K, et al. A scoping review of intersectoral action for health equity involving governments. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO). Framework and statement: consultation on the drafts of the “Health in All Policies Framework for Country Action” for the Conference Statement of 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion. 2013. Available at http://www.healthpromotion2013.org/conference-programme/framework-and-statement. Accessed 10 Oct 2013.

- 17.Rudolph L, Caplan J, Mitchell C, Ben-Moshe K, Dillon L. Health in All Policies: improving health through intersectoral collaboration. Discussion Paper. September 18, 2013. Institute of Medicine. Available at http://www.iom.edu/Home/Global/Perspectives/2013/HealthInAllPolicies.aspx. Accessed 1 Feb 2014.

- 18.Freiler A, Muntaner C, Shankardass K, Mah CL, Molnar A, Renahy E, et al. Glossary for the implementation of Health in All Policies (HiAP) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:1068–72. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burris S, Hancock T, Lin V, Herzog A. Emerging strategies for healthy urban governance. J Urban Health. 2007;84:154–63. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996;24(6):1073–87. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corburn J. Bringing local knowledge into environmental decision making: improving urban planning for communities at risk. J Plan Educ Res. 2003;22:420–33. doi: 10.1177/0739456X03022004008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasanoff S. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. London: Routledge. 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-40329-0.

- 23.Chevron modernization project, draft environmental impact report. 2014. Available http://chevronmodernization.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/4.3_Air-Quality.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2014.

- 24.US Census Summary File 3a. 2010. Summarized here, http://www.city-data.com/city/Richmond-California.html. Accessed 7 Sept 2013.

- 25.Contra Costa Health Services (CCHS). Community health indicators for Contra Costa County. Available at http://cchealth.org/health-data/hospital-council/2010/pdf/2010_community_health_indicators_report_complete.pdf. 2010. Accessed 11 Jul 2013.

- 26.Bohan S, Kleffman S. shortened lives: where you live matters. Contra Costa Times. 2010. Available at http://www.contracostatimes.com/life-expectancy. Accessed 12 Nov 2012.

- 27.Connelly C. Bold Richmond plan aims at ‘Health and Wellness.’ Richmond confidential, June 7, 2011. Available at http://richmondconfidential.org/2011/06/07/richmond-plans-for-a-healthier-future/. Accessed 24 Feb 2014.

- 28.Rodgers R. Richmond city leaders form partnership to improve health, reduce violence. Contra Costa Times, March 27, 2013. Available at http://www.contracostatimes.com/ci_22880066/richmond-city-leaders-form-partnership-improve-health-reduce. Accessed 23 Jan 2014.

- 29.Weintraub D. Richmond’s new priority: taking health seriously, New York Times, April 3, 2010. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/04/us/04sfpolitics.html?_r=0. Accessed 7 Feb 2014.

- 30.McEwen B. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2008;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Scientific Council (NSC) on the Developing Child. The developing child, excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing brain: Working Paper # 3. 2009. Available at http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/reports_and_working_papers/working_papers/wp3/. Accessed 3 Dec 2013.

- 32.Powell J. Structural racism: building upon the insights of John Calmore. N C Law Rev. 2007;86:791–816. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richmond City of. Health Initiatives. 2014. Available at http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/index.aspx?NID=2574. Accessed 29 Dec 2013.

- 34.Said C. Richmond pushes forward with eminent domain plan. San Francisco Chronicle, 2013. Available at http://www.sfgate.com/realestate/article/Richmond-pushes-forward-with-eminent-domain-plan-5073950.php. Accessed 19 Dec 2013.

- 35.Brown J. Contra Costa tables controversial jail expansion. Richmond Confidential, 2012. Available at http://richmondconfidential.org/2012/09/07/contra-costa-tables-controversial-jail-expansion/. Accessed 21 Oct 2013.

- 36.Rodgers R. Contra Costa supervisors OK Chevron Richmond tax deal. Contra Costa Times, 2013. Available at http://www.contracostatimes.com/west-county-times/ci_24114907/contra-costa-supervisors-ok-chevron-richmond-tax-deal. Accessed 11 Nov 2013.

- 37.Jones C. UC picks Richmond for Lawrence Berkeley Lab Campus. San Francisco Chronicle, 2013. Available at http://www.sfgate.com/education/article/UC-picks-Richmond-for-Lawrence-Berkeley-lab-campus-2675669.php. Accessed 15 Oct 2013.

- 38.Geluardi J. The man behind Richmond’s renaissance. East Bay Express, 2011. Available at http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/the-man-behind-richmonds-renaissance/Content?oid=2647128. Accessed 1 Aug 2013.

- 39.Skocpol T. Targeting within universalism: politically viable policies to combat poverty in the United States. In: Jencks C, Peterson PE, editors. The Urban Underclass. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 1991. pp. 411–36. [Google Scholar]