Abstract

Context:

The Food Safety and Standards Act have redefined the roles and responsibilities of food regulatory workforce and calls for highly skilled human resources as it involves complex management procedures.

Aims:

1) Identify the competencies needed among the food regulatory workforce in India. 2) Develop a competency-based training curriculum for food safety regulators in the country. 3) Develop training materials for use to train the food regulatory workforce.

Settings and Design:

The Indian Institute of Public Health, Hyderabad, led the development of training curriculum on food safety with technical assistance from the Royal Society for Public Health, UK and the National Institute of Nutrition, India. The exercise was to facilitate the implementation of new Act by undertaking capacity building through a comprehensive training program.

Materials and Methods:

A competency-based training needs assessment was conducted before undertaking the development of the training materials.

Results:

The training program for Food Safety Officers was designed to comprise of five modules to include: Food science and technology, Food safety management systems, Food safety legislation, Enforcement of food safety regulations, and Administrative functions. Each module has a facilitator guide for the tutor and a handbook for the participant. Essentials of Food Hygiene-I (Basic level), II and III (Retail/ Catering/ Manufacturing) were primarily designed for training of food handlers and are part of essential reading for food safety regulators.

Conclusion:

The Food Safety and Standards Act calls for highly skilled human resources as it involves complex management procedures. Despite having developed a comprehensive competency-based training curriculum by joint efforts by the local, national, and international agencies, implementation remains a challenge in resource-limited setting.

Keywords: Competency-based training, curriculum development, food safety regulators, food safety

Introduction

The World Health Assembly in the year 2000 (WHA 53.15) adopted a resolution to improve food safety with the goal of reducing the health hazards that exist throughout the food chain from production to consumption. The Indian Government too has long been committed to improving food safety, but until recently, priority was to address the serious challenges of food adulteration under the Prevention of Food Adulteration (PFA) Act, 1954.(1)

However, the PFA Act was largely punitive, and it had limitations in keeping pace with modern technology and preventative approach. All earlier food regulatory laws involved range of ministries and departments making it more complex to enforce. Therefore, the Government of India enacted a comprehensive Act ‘The Food Safety and Standards (FSS) Act’ 2006 that emphasizes on training and awareness program on food safety for food business operators, regulators, and consumers.(2) The act aims for decentralization of licensing for food products within a reasonable timeframe and encourages self-regulation through the process of food recall. The law mandated the setting up of Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) as a single reference point for all matters relating to Food Safety and Standards, Regulations, and Enforcement. The 11th Five-year plan (2007-2012) too highlighted the importance of improving food safety as a priority within its framework for better consumer protection.(3)

With food safety and standards gaining a high priority on the national and international agenda, there is an opportunity to transform the food safety landscape globally.(4) To keep pace with the growing demand on safety and quality, there is an urgent need to train and equip food regulators namely the Food Safety Officers (FSOs) and Designating Officers (DOs) in India. Their training and skill enhancement will equip them to sensitize the food business operators and ensure that food handlers are following food hygiene and safety norms. Thus, there is need for developing an incremental program of training qualifications to build capacity of FSOs to inspect, audit, and conduct food surveillance to ensure food safety and hygiene confirming to international standards. The training for FSOs thus focuses on international standards in Good Hygienic Practice (GHP), Food Safety and Quality Management (FSQM), and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP).(5,6) At the same time, the Designating Officers (DOs) need training for monitoring and evaluation, investigating food-borne illness outbreak, preparing food safety plan of their district, and communicating with external agencies to bring about behavior change among food business operators and food handlers across the country.(7) The DOs play a role of providing supportive supervision and act as mentors for FSOs during the initial period following recruitment.

Shortage of food regulatory staff in both central and state food regulation system and the paradigm shift of focus from prevention of food adulteration to food safety have placed significant demand for new knowledge and skills. Further to this, loss of employees from regulatory system to other specialties, coupled with the growing complexity of food manufacture, processing, distribution, and retail systems, require recruitment of professionals and development of novel approaches that surpass old traditional methods.(8) The US Government supported the need to train food regulators in food safety management under the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) in 2005 for the need 10 years later, and the benefits of this initiative are visible today.(9)

Food regulators are a major public health workforce charged with ensuring food safety to protect the health and wellbeing of the population. In order to equip the food regulatory workforce with knowledge and skills, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) conceived the idea of providing high quality training material matching to national and international standards to all food regulatory authorities in the country. The Indian Institute of Public Health, Hyderabad India (IIPHH) led the development of training curriculum on food safety with technical assistance from the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), UK and the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), India. The exercise was to facilitate the implementation of new Act by undertaking capacity building through a comprehensive training program. This was the “first of its kind” activity undertaken to identify the competencies needed under the new FSS Act, and accordingly training curriculum and materials were developed.(10)

The objectives of our undertaking were to:

Identify the competencies needed among the food regulatory workforce in India.

Develop a competency-based training curriculum for food safety regulators in the country.

Develop training materials for use to train the food regulatory workforce.

Materials and Methods

Training needs of food regulators

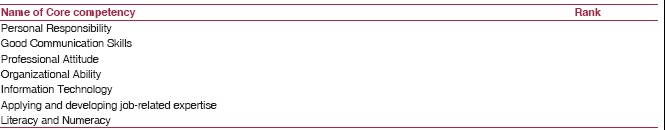

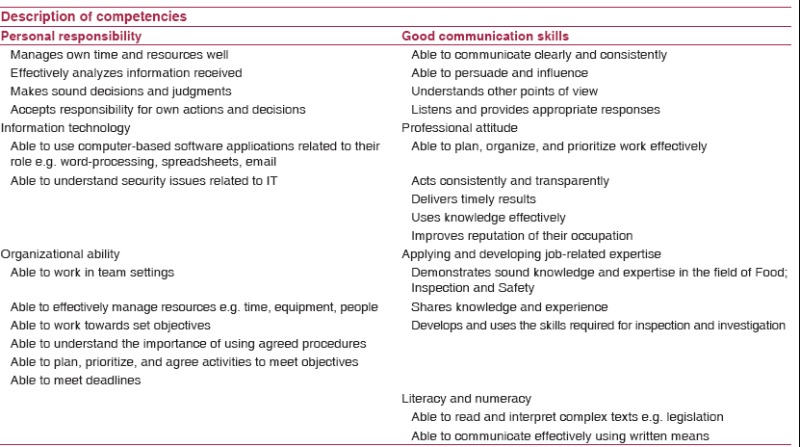

A competency-based training needs assessment was conducted before undertaking the development of the training materials. This was done by administering a competency importance rating scale (CIRS) to food regulators congregated for an orientation program. The food regulators belonged to senior cadre (equivalent to designating officers), were mostly men, and were working with the state and central government department of health and family welfare. They were from Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujrat, Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. The food regulators were asked to rank the professional competencies laid out in the CIRS. The material for the training was developed based on the outcome of this survey and is further elaborated in the result's section. The core competencies' components were personal responsibility, good communication skills, information technology, and professional attitude, organizational ability, applying and developing job-related expertise, literacy and numeracy, research and use knowledge effectively.

The professional competencies aimed at food regulators, required them to demonstrate a thorough understanding of FSS Act (legislation), effectively undertake the inspection and auditing of food establishments, carry out sampling procedures for food items, and identify the range of hazards (biological, chemical, physical) that result from food business activities. Hence, food regulators needed training in microbiology, food surveillance, laboratory systems, and detection of contaminants in food establishment units, identifying emerging food-borne infections, and drawing up food safety plan for their jurisdiction.

Curriculum development process

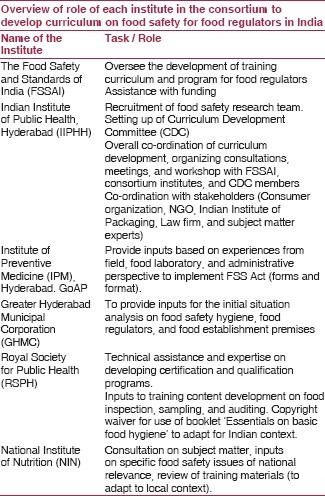

FSSAI outsourced the development of long-term training program to IIPHH to put together a comprehensive and implementable set of training material, which can be used by the various states with modifications, if required. The training outputs had to suit the requirements of FSSAI rules and regulations. At the onset, a Curriculum Development Committee (CDC) was formed comprising of Indian Institute of Public Health (IIPHH), the Institute of Preventive Medicine, Hyderabad, National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), and the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) of the UK. Subsequently, experts from law firm, NGO, policy makers, public health specialists, packaging industry, and retail sector too were engaged.

The curriculum development process involved desk review of appropriate occupational standards, competencies, legislative frameworks, and international practices on food safety. A set of learning objectives (syllabus) and learning outcomes (assessment) were determined. There was simultaneous engagement of stakeholders to review the overall program rationale, course structure, course content, and assessment at all levels of training.

During the curriculum development process, field visits and interviews were conducted with food regulatory authorities, food analysts, culinary academy, experts from packaging and retail industry, and the staff of the municipal corporation. The RSPH team gave detailed inputs to the material and visited on three occasions to review and revise the materials. There was regular electronic exchange of materials developed for continuous review and inputs by the RSPH. Few months into the project, the CDC which had members predominantly from Andhra Pradesh was expanded to include food regulatory members from other Indian states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Delhi, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. Regional organizations were consulted for their expertise in law, packaging, retail, and consultation on qualification and certification. The expanded CDC met at a final workshop after the draft version of curriculum was circulated for further review and inputs by the members. The workshop helped finalize the content and duration for food regulator's training program and the levels of training for food handlers. The expanded CDC re-examined the final curriculum and training material for appropriateness and relevance to Indian context, following which the documents were edited, designed, and printed.

A research team was formed and charged with the following:

Reviewing documents, guidelines from National and International Institutes and Government departments.

Procuring documents and educational materials from academic and research institutions, Governmental organizations, and international collaborators.

Literature search using databases such as Pub Med, Medline, science direct, and Google Scholar.

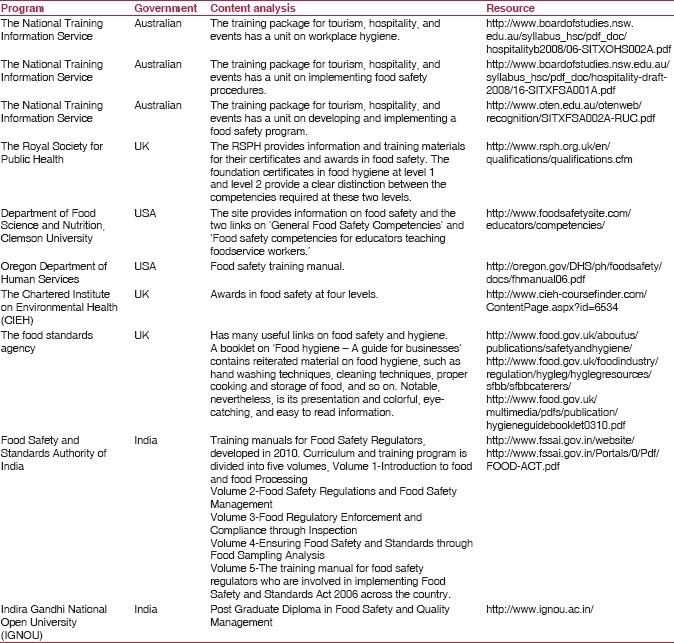

Brief note on the review of literature

The program was designed, based on the relevant occupational needs, to provide essential underpinning knowledge, competence, and understanding about food safety and standards. It will equip designating officers to lead the food safety strategy, planning and its implementation, monitoring and surveillance in their districts, and enable food safety officers to educate and inform food handlers about basic good practice in food safety and hygiene and to deliver safe food to the consumers. In keeping with these goals, we outline the available sources and important materials for developing both a competency framework as well as a curriculum for training on food safety and hygiene.

The curriculum for food regulators

The purpose was to have a set of training handbooks, facilitator guides with checklists for field visits, on job training, and assessments at the end of each module and log book for food regulators. The idea was to provide high quality, accessible set of training materials for food regulators.

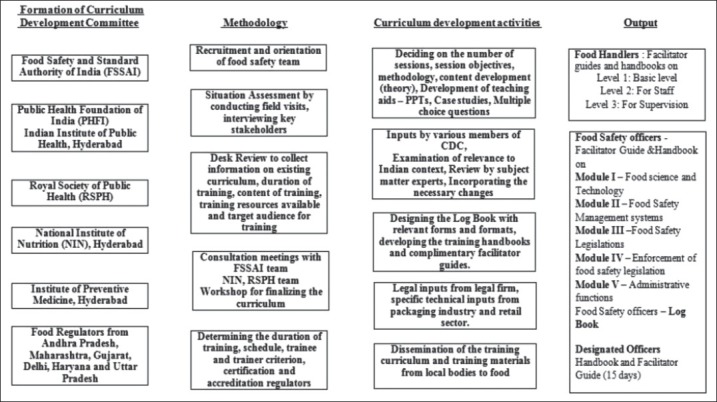

The Figure 1 depicts the comprehensive approach adapted to develop competency-based training curriculum and program for food regulators. The CDC involving national and international experts was formed and brainstorming sessions held for development of competency-based curriculum. The research team undertook review of existing courses and materials on food safety (ten resources mentioned above), best practices in the field, and what the future needs of food regulators would be in the ever changing environment (through the CIRS survey). The FSO's training was designed with the objective to close the ‘service gap’ that emerged due to the new FSS Act to include implementing food safety strategy, monitoring and surveillance in their districts, and enable food safety officers to educate and inform food handlers. This activity was an additional role when compared to their training under the earlier PFA Act. A wide range of topics were covered in developing the training material, right from essentials of food hygiene to HACCP and change management. The process of developing the new training program took 18 months, and it involved expertise from multiple disciplines on multitude of food safety issues at various levels.

Figure 1.

Curriculum development methodology for food regulators

The curriculum was built on specific skills required as per the FSS Act to include details of the Act, its enforcement, knowledge on basic food hygiene, basic epidemiology, food inspection, sampling requirements, quality management in food processing units, monitoring and evaluation, developing food safety plan, surveillance, etc.(11,12,13) The course was designed to equip FSOs in their new roles to fulfill their job responsibilities such as issuing licenses following inspection.

For instance, teaching methodology for food premise inspection training includes: Use of a premises inspection checklist and audit guide and work through the inspection/audit process incorporating the underpinning knowledge e.g. cleaning requirements/methods, HACCP as it would be used in relation to practice. The food regulators need to familiarize themselves with the training material developed specifically for food handlers. This material was developed for three levels (basic, advanced, and managerial) in the sectors of manufacturing, retail, and catering. Presuming that a large amount of the underpinning knowledge has already been delivered, much of the teaching would be trainee discussion as to what they would be examining and why and how they would elicit information from a proprietor.

The training program was developed for a period of 6 months, at the end of which the participants will receive certification. The training includes case studies, classroom discussions, interactive sessions, practical assignments, field visits, and exercises. These classroom sessions will provide the content necessary to do the practical assignments and help develop competencies.

Course design for the target audience

Food safety officers

The training program for FSOs was designed to comprise of 5 modules: Food science and technology, food safety management systems, food safety legislation, enforcement of food safety regulations, and administrative functions. Each module accompanies a facilitator guide for the tutor/facilitator and a handbook for the trainee/participant. The duration of training for each module differed based on the content and consensus formed amongst the CDC members. Each module could be offered as independent training program of specific time duration to allow the food regulators to take time off their work schedule.

Module 1 - Food Science and Technology: The major topics covered in this module include disease surveillance, food processing, food packaging, investigation of food outbreaks, etc. The duration of this module is of 14 days.

Module 2 - Food Safety Management Systems (FSMS): Some of the major sections in this module include FSMS, risk analysis, risk management, food traceability, and recall. FSMS addresses the “farm-to-fork” approach by giving priority to consumers' demand and the right to access to safe and quality food. To achieve this, an efficient and effective food safety management system along the food chain needs to be established and implemented. The duration of this module is 7 days.

Module 3 - Food Safety Legislations: The major sections in this module are food-related Acts, roles and responsibilities of food regulators, licensing, registration, etc. This module aims to fill the legislation gaps for each professional working in food sector with a common “from farm to fork” food safety approach covering all related FSSA regulations. Since it is difficult to read and comprehend all the legislations, simple and comprehensible language was used in the training besides case studies about regulations to make it easier to understand. The duration of this module is 10 days.

Module 4 - Enforcement of Food Safety Regulations: This module covers the practical aspects through field visits with work involving inspection at various food establishment units. The module is for 20 days duration and comes with a log book for the participants. The log book consists of various forms to aid in inspection, auditing, and sampling of food item, and this needs to be maintained as the activities carried out during the field visits.

Module 5 - Administrative Functions: The major part of this module involves developing food safety plan for Panchayat body or Municipal body. The module also contains session on interpersonal and communication skills that are required to develop interface with external stakeholders such as media, district administrators, food producers, and school authorities. The forms contained in the log book are as per the norms prescribed by the FSSAI under the FSS Act. The duration of the module is 14 days.

Designated officer's (DO's)

The training program for DO's includes management and leadership component in addition to the content intended for FSOs. This is to enable DOs to lead the food safety strategy in their districts and includes sessions on how to develop external relationships both with industry and public sector partners. The development of district food safety plans and building a case for legal action is also included in this module. The training course planned for DOs consists of mentoring skills, management skills, disease surveillance, inspection and auditing techniques and importantly change management skills.(10) A handbook and a facilitator guide were developed to provide 15 days training program for Designated Officers.

Results

After evaluation of the CIRS, there were 37 respondents to the survey, and two patterns emerged from the way the participants filled the forms. One set of participants (26) rated the competencies while the remaining 11 participants ranked the competencies as per our instructions. The evaluation of the two data sets was done separately, and in the group of 26 participants who rated the competencies, the mode was 1 for most of the core competencies, except good communication skills (2) and literacy and numeracy which had a mode of 3. These results show that the participants felt that all the core competencies were equally important.

For the professional competencies among the 26 participants, on a scale of 1 to 15, the mode from ratings of participants showed that all the professional competencies were rated either 1 or 2. In the group of 11 participants, the ranking for the core competencies indicated highest for personal responsibility and professional attitude. Low preference was given for literacy, numeracy, and IT skills.

The mode for the professional competencies shows the competencies with highest preference was ‘Able to demonstrate a thorough understanding of existing domestic food law and forthcoming legislation’ and ‘Able to identify the range of hazards that may result from food business activities and identify the associated health risks,’ while those with lowest preference include ‘Able to prepare a prosecution case file or a report to the relevant person’ and ‘Able to assimilate interpret and apply new legislation.’

The curriculum outline was structured as five thematic modules. Each module had one or more sessions with the following: Session learning objectives identifying what the learners are expected to be able to understand and/or do, once they have completed the session; approximate duration of the session; teaching methodology and a session content overview to give an idea for trainers as to what to expect. The facilitator guide included guidelines and suggestions for instructors and trainers for developing the specific contents of the lesson. There are steps to orient the instructors and trainers as to how the lesson content should relate to the normal roles and responsibilities of the target learner group(s).

The training aids developed for the facilitator include instructions, notes, power point presentations, case studies, checklists, forms as per FSS requirement and are accompanied by handbooks for anyone undergoing the training. Assessment in the form of multiple choice questions along with the answer keys is provided at the end of each module in the facilitator guide to test the FSOs. Reference materials which provide information on additional reading sources, reference articles in the form of documents (hard and electronic copies), e-learning courses and materials, manuals, reference guides etc., are provided at the end of each module. Reference materials can serve as a background reading in case the duration of the training has to be further shortened.

The training materials for DOs include aspects of leadership, change management, food safety planning in addition the topics covered under the FSO training program. As Designated Officers are expected to provide supportive supervision to the FSOs, it is necessary that the former are familiar with function of FSOs and get equipped with additional skills.

The following training materials were developed for food handlers and food regulators:

Level 1 - Essentials of Food Hygiene-I (Basic level): Available in English, Urdu, Hindi, and Telugu. Handbooks and facilitator guides including posters for the training of Food handlers.

Level 2 - Essentials of Food Hygiene-II (Retail/ Catering/ Manufacturing): An advanced level module elaborating the importance of each component at level 1 such as time-temperature control, cross-contamination prevention, proper cleaning and sanitizing and good personal hygiene. Components on food law and high risk food were added to this level.

Level 3 - Essentials of Food Hygiene-III (Retail/ Catering/Manufacturing): This advanced level caters for supervisory or managerial cadre and requires certification if they were to train food handlers at level 1 and 2. Effective Training Guidelines on how to use the training materials, how to use training tools effectively, exercises to help memory retention, and emphasis on basic, critical information was provided in the Facilitator Guide for training food handlers. The emphasis was given on visual aids such as pictures, posters, Dos and don'ts in training materials targeted at food handlers.

Discussion

The current formal professional education system trains trainers to implement the existing curriculum. However, with rapid advancement in technology, development of science or enactment of new laws, there emerges the need for development of new curriculum. It is further more challenging if the new curriculum requires multiagency, multi-level, and multidisciplinary input to the training program. Unlike in the U.S. and U.K., in low- middle income countries, there is lack of resources to invest in curriculum development of emerging discipline.(14,15) The need for food regulator training varies depending on the jurisdiction the food regulators work in. Thus, training and education of food regulators, particularly in the context of professional development, rapidly advancing technology, and growing consumer awareness, is very challenging. A multidisciplinary approach to train and educate the food regulatory workforce to ensure ‘fitness to practice’ in their current role provides an opportunity to improve food safety and standards in the country. Training on systems and procedures to ensure uniformity and consistency across the food regulatory workforce was envisaged. Hence, developing a uniform, structured course with competency-based learning objectives, methodology, appropriate content and relevance to new roles of food regulatory workforce was critical.

In the past, the training of food regulators namely the food inspectors under the PFA Act was of 3-months duration.(16) This course was accredited by Directorate General, Health Service and was conducted after recruitment of food inspectors under the PFA Act in India. There are other courses offered by various Institutes but less preferred because of their longer duration and are less known to the regulatory authorities.

The FSS Act has redefined the role of all food authorities and their functionaries namely FSOs and DOs to ensure safe and wholesome food nationwide. They are expected to educate and inform the business operators on food safety, food quality and regularly undertake inspection and auditing of local food establishments. To respond to this need, capacity building programs were initiated for existing food regulatory workforce and FSSAI organized induction programs for FSOs and DOs on a fast track basis to train over two thousand food regulators over 3-4 month time frame. A basic understanding of the FSS Act and the corresponding responsibilities of food handlers and officers was developed for the in-house five day orientation program in batches of 25-30 trainees (Training manual for food safety regulators 2010-Volume I to V).(17)

This curriculum developed focuses on food regulators as the target audience. Academic institutions have a crucial role to play in capacity building for the implementation of FSS Act across the country. The role for facilitators consists of serving as resource personnel, subject matter experts, and contributors to the lesson contents and sessions. In the case of senior DO's, they can be a part of ‘training of trainers’ system as they have considerable capacity in specific parts of food regulation, or have previously received relevant training and can help prepare others to serve as instructors or trainers.

The formal training course for the food regulators needs to be approached for accreditation by National Qualifications Body. We recommend the establishment of a National Quality and Standardization authority and the development of a framework for standard setting and regulation. The FSSAI under the Ministry of Health needs to dedicate resources including time every year to conduct in-service training programs if food regulators are to make rapid and visible impact in the implementation of FSSA. There is a need for a formal in-service training program and refresher training at regular intervals in order to facilitate widespread curriculum change.(18,19)

Limitations

One of the drawbacks was that due to resource and time constraint, we were unable to test the training materials. An opportunity to carry out the training program using the training curriculum and materials developed by CDC would have helped us to make further changes.

Instructions

Given below is a list of core and professional competencies. Please rank them based on how you perceive their value to your work performance (1 being the highest and 7 the lowest for core competencies; and 1 being the highest with 15 being the lowest of professional competencies). Each of the core competencies are described below.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India and Department of Health, UK for providing funding for the development of training curriculum and materials. We acknowledge the contribution of all the members of curriculum development committee and all the individuals, universities, professional bodies, and non-governmental organizations that submitted responses to the consultation exercise, whose comments were invaluable in developing the curriculum.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.PFA. Prevention of Food Adulteration Act: New Delhi, Confederation of Indian Industry. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food Safety and Standards Act of 2006. The Gazette of India. Ministry of Law and Justice. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 12]. Available from: http://www.fssai.gov.in/Portals/0/Pdf/FOOD-ACT.pdf .

- 3.Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012), AQSIQ. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.dst.gov.in/about_us/11th-plan/rep-csir.pdf .

- 4.Taylor MR. Will the food safety modernization act help prevent outbreaks of foodborne illness? NEngl JMed. 2011;365:e18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FAO/WHO. FAO Food and Nutrition paper 76. Rome: FAO; 2003. Assuring Food Safety and Quality: Guidelines for strengthening national food control systems. [Google Scholar]

- 6.FAO/WHO. FAO Food and Nutrition paper 86. Rome: 2006. Guidance to Governments on the Application of HACCP in small and/or less-developed food businesses. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vemula SR, Kumar RN, Kashinath L, Bhaskar V, Polasa K. Economic Impact of a Food Borne Disease Outbreak in Hyderabad – A case study. JNutrDiet. 2010;47:246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph CJ, Wojtala G, Kaml C. Training in an Integrated Food Safety System: Focus on Food Protection Officials: Food Safety Magazine? [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/article.asp?id=4018andsub=sub1#Corby .

- 9.Curriculum. International food protection training institute. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.ifpti.org/training/curriculum .

- 10.Institute of Public Health, Hyderabad, to develop curriculum, programme on food safety. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.harneedi.com/index.php/pharma/2291-institute-of-public-healthhyderabad-to-develop-curriculum-programme-on-food-safety .

- 11.International Life Sciences Institute -India. A Surveillance and Monitoring System for Food Safety for India. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.ilsi-india.org/PDF/Conf.%20recommendations/Food%20and%20Water%20Safety/Food%20safety%20Surveillance%20and%20Monitoring%20System%20for% .

- 12.Food Protection Plan: An Integrated Strategy for Protecting the Nation's Food Supply. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijayshree O. Management of Change. UNDP and Department of Personnel and training. Government of India. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 16]. Available from: http://persmin.gov.in/otraining/UNDPProject/undp_modules/MgtOfChange.pdf .

- 14.Competency to Curriculum toolkit. Developing Curricula for Public Health WorkersCenter for Health Policy Columbia University School of Nursing and Association of Teachers of Preventive Medicine. 2008 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christopher B Reznich, Anderson William A. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 16];A Suggested Outline for Writing Curriculum Development Journal Articles: The IDCRD Format, Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 13:4–8. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1301_2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1301_2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevention of Food Adulteration. Chapter 10. The Prevention of Food Adulteration Act 1954. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/uploads/codesmanual/MMVol-II/Medical_II_Ch10_data.htm .

- 17.Training manual for food safety regulators: Volumes 1 to 5. Food Safety and Standards Authority of India. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudershan RV, SubbaRao GM, Rao P, VardhanaRao MV, Polasa K. Knowledge and practices of food safety regulators in Southern India. Nutr Food Sci. 2008;38:110–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudershan RV, Rao P, Polasa K. Food safety research in India: A review. As JFood Ag-Ind. 2009;2:412–33. [Google Scholar]