Abstract

Though choroidal osteoma is a rare benign tumor, associated choroidal neovascularization (CNV) can be a cause of severe visual loss. A nine-year-old boy presented with one-month history of decreased vision in left eye. Upon a complete ophthalmologic examination, including fundus fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography, he was diagnosed with choroidal osteoma-related subfoveal CNV in the left eye. The CNV was associated with subretinal hemorrhage, subretinal fluid, and cystoid macular edema. Owing to the young age and subfoveal localization of the CNV, intravitreal ranibizumab injection was performed on this patient after a detailed discussion with the parents of its safety profile. No local or systemic complications were noted. No recurrence of CNV lesion was noted during 30 months of follow-up, and the vision was maintained. This report shows the favorable outcome of intravitreal injection of ranibizumab in choroidal osteoma-related CNV in a child.

Keywords: Children, choroidal neovascularization, choroidal osteoma, cystoid macular edema, ranibizumab

Introduction

Choroidal osteoma is a rare benign tumor typically occurring in young females; however, males and children less than age ten have been diagnosed as having a choroidal osteoma.[1] Development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) may lead to severe visual loss.[1] Recently, intravitreal ranibizumab injection has been used with success in the treatment of the CNV associated with choroidal osteoma in adults[2] as well as children.[3] Also, there are recent reports of favorable outcome of ranibizumab injection in children for CNV secondary to varied etiologies.[4,5] Herein, we report the results of ranibizumab for treating osteoma-related CNV in a child. We also describe the future course of the lesion over a follow-up of 30 months.

Case Report

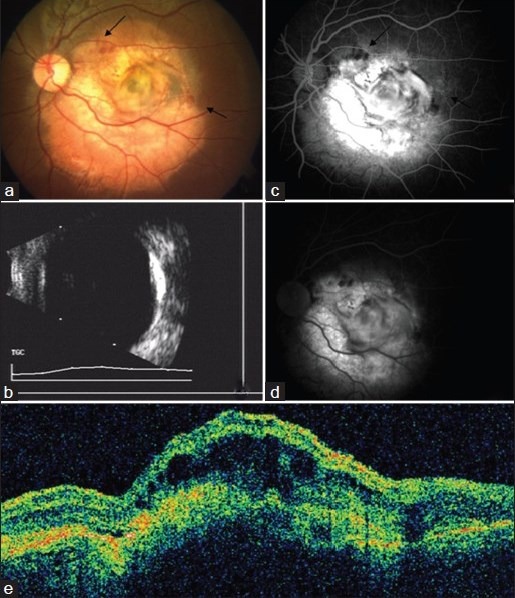

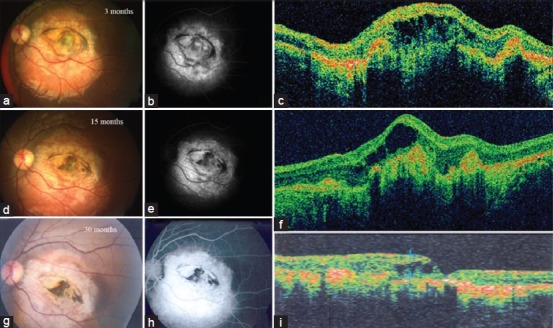

A nine-year-old boy presented with the complaint of decreased vision in left eye since one month. There was no significant medical or family history. On examination, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/400 in the left eye. Anterior segment examination of both eyes and fundus examination of the right eye was unremarkable. Fundus examination of the left eye showed a slightly elevated yellowish lesion on the posterior pole [Figure 1a]. Fresh subretinal hemorrhages were noted in the center of the lesion. The B-scan ultrasound showed a subretinal lesion with high surface reflectivity, persisting at low gain with orbital shadowing behind, suggestive of choroidal osteoma [Figure 1b]. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) in the left eye showed early patchy hyperfluorescence [Figure 1c] with late staining of the choroidal osteoma [Figure 1d]. In the center of the osteoma, early lacy hyperfluorescence [Figure 1c] leaking in the late phase [Figure 1c] was noted, indicative of classic CNV. There were also areas of blocked fluorescence corresponding to the subretinal hemorrhages seen clinically. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed a subfoveal CNV complex with gross CME overlying the CNV with subretinal fluid extending to the fovea [Figure 1e]. A diagnosis of left eye choroidal osteoma with CNV was made. After a detailed discussion with the parents regarding the risks and the safety profile of intravitreal ranibizumab in children, the patient received intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis-Novartis) injection (0.5 mg in 0.05 ml) in the left eye. Since the patient belonged to another country, monthly follow-up could not be maintained. After three months, the CNV appeared regressed with resolution of subretinal hemorrhage clinically [Figure 2a], staining of scar with no leakage on FFA [Figure 2b], and disappearance of fluid on OCT [Figure 2c]. CME showed only partial resolution as confirmed on OCT and FFA.

Figure 1.

Left eye, at presentation (a) Fundus photograph showing choroidal osteoma with choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and subretinal hemorrhage (arrows) (b) B-scan showing hyperechoic osteoma with orbital shadowing (c) Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) early phase showing hyperfluorescence of CNV and blocked fluorescence of hemorrhage (arrows) (d) FFA late phase showing late leakage of CNV (e) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan showing retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) disruption, overlying cystoid macular edema (CME) and minimal subretinal fluid (SRF) suggestive of active CNV

Figure 2.

Left eye, three months post-first lucentis injection (a) Fundus photograph showing choroidal osteoma with disciform scar and resolved subretinal hemorrhage (b) FFA showing staining of disciform scar and absence of leakage (c) OCT showing resolved SRF and persistent CME. Fifteen months post-first injection (d) Fundus photograph and (e) FFA showing same picture (f) OCT showing persistent CME despite three injections. Thirty months post-first injection (g) Fundus photograph and (h) FFA showing osteoma with stable scar without any recurrence of CNV (i) OCT showing persistent, though reduced, overlying CME

In view of persistent CME, despite the scarring CNV, two more injections of ranibizumab were administered at three monthly intervals. Since the cystic spaces were still persistent after third injection and CNV appeared completely scarred on OCT, it was decided to observe and defer any further injections. As noted over further follow-ups, the CNV remained inactive without any recurrence [Figure 2d and e]. However, complete regression of cystic spaces was still not achieved [Figure 2f]. The visual acuity of left eye was maintained at 20/400. The last examination of the patient, done at 30 months by a local eye specialist, showed a stable picture with disciform scar [Figure 2g and h] and persistent, though reduced, overlying CME [Figure 2i]. The report of the last visit was sent to us by the local specialist.

Discussion

We document a rare case of choroidal osteoma-related CNV in a child, treated by the use of intravitreal ranibizumab injection without local or systemic adverse effects. CNV is the most frequent cause of visual loss in choroidal osteoma, with more than half of patients expected to develop CNV.[1] Laser photocoagulation has limited efficacy in the treatment owing to lack of pigment in the tumor and atrophy of overlying retinal pigment epithelium[1] and was tried in children with limited success.[6] The results of surgical removal have also been associated with poor visual results.[7] Recently, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents have been used with success in osteoma-related CNV in adults[2] and children.[3]

Kubota-Taniai M et al. recently reported successful treatment of CNV associated with choroidal osteoma with two intravitreal injections of bevacizumab in a 12-year-old girl and no recurrence till a follow-up of four years.[8] In pediatric population, as reported by Avery et al.,[9] use of ranibizumab instead of bevacizumab may lower systemic exposure given its much shorter serum half-life and as found in several animal studies. There is a recent report of intravitreal ranibizumab use in an 11-year child for CNV associated with choroidal osteoma.[3] The follow-up period was two years.

In the present case, regression of CNV was noted after the first intravitreal injection of ranibizumab. However, the CME was persistent overlying the scarred membrane despite two more injections and till a follow-up of 30 months. Persistent CME overlying scarred CNV can be explained by the presence of thinned degenerated retinal pigment epithelium overlying the choroidal osteoma.[1] Such finding of persistent cystic cavities on OCT in eyes with disciform scars (secondary to wet age related macular degeneration treated with PDT) was also reported previously by Salinas-Alamán et al.[10] They suggested that in cases where intraretinal fluid is seen on OCT and no leakage is seen on FFA (called as false positives), a disciform scar should be ruled out in the fundus examination, because in these cases, no treatment is indicated. We also noted a similar course in our case. The patient maintained his vision over entire follow-up, and there was no recurrence of CNV despite persistent cystic maculopathy.

In conclusion, intravitreal ranibizumab was effective for CNV associated with choroidal osteoma in our patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Shields CL, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;33:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song MH, Roh YJ. Intravitreal Ranibizumab in a patient with choroidal neovascularisation secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1745–6. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vayalambrone D, Misra A. Paediatric choroidal osteoma treated with ranibizumab. BMJ Case Rep 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007446. piibcr2012007446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin P, Shields CL, Ramasubramanian A, Brown GC, Shields JA. Ranibizumab for coloboma-related choroidal neovascular membrane in a child. J AAPOS. 2009;13:616–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohly RP, Muni RH, Kertes PJ, Lam WC. Management of pediatric choroidal neovascular membranes with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents: A retrospective consecutive case series. Can J Ophthalmol. 2011;46:46–50. doi: 10.3129/i10-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avila MP, El-Markabi H, Azzolini C, Jalkh AE, Burns D, Weiter JJ. Bilateral choroidal osteoma with subretinal neovascularisation. Ann Ophthalmol. 1984;16:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster BS, Fernadez-Suntay JP, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, D’Amico DJ. Surgical removal and histopathologic findings of subfoveal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:273–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubota-Taniai M, Oshitari T, Handa M, Baba T, Yotsukura J, Yamamoto S. Long-term success of intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1051–5. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avery RL. Extrapolating anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy into pediatric ophthalmology: Promise and concern. J AAPOS. 2009;13:329–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas-Alamán A, García-Layana A, Maldonado MJ, Sainz-Gómez C, Alvárez-Vidal A. Using optical coherence tomography to monitor photodynamic therapy in age related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]