SUMMARY

Coordinated enzymatic reactions regulate blood clot generation. To explore the contributions of various coagulation enzymes in this process, we utilized a panel of aptamers against factors VIIa, IXa, Xa, and prothrombin. Each aptamer dose-dependently inhibited clot formation, yet none was able to completely impede this process in highly procoagulant settings. However several combinations of two aptamers synergistically impaired clot formation. One extremely potent aptamer combination was able to maintain human blood fluidity even during extracorporeal circulation, a highly procoagulant setting encountered during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Moreover, this aptamer cocktail could be rapidly reversed with antidotes to restore normal hemostasis, indicating that even highly potent aptamer combinations can be rapidly controlled. These studies highlight the potential utility of using sets of aptamers to probe the functions of proteins in molecular pathways for research and therapeutic ends.

INTRODUCTION

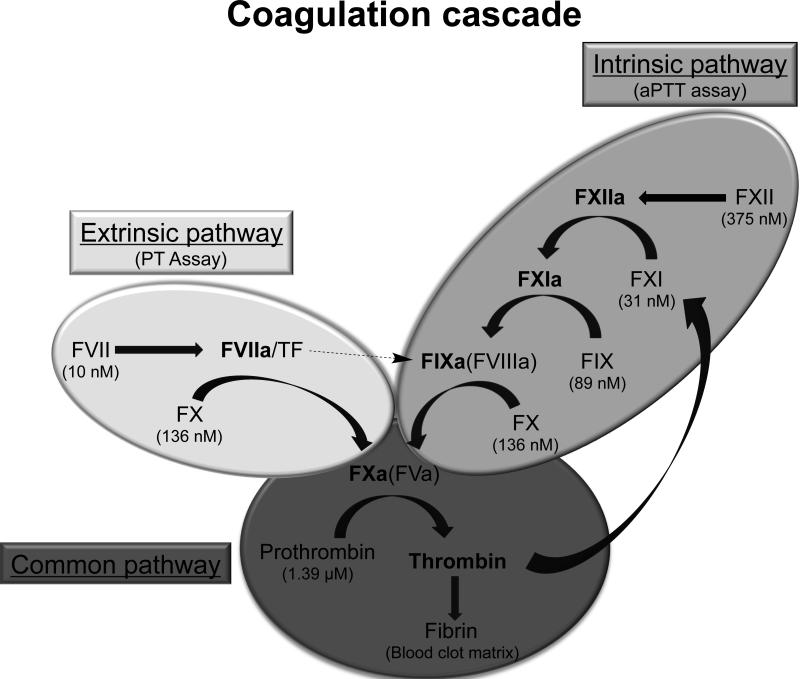

Fibrin blood clot formation is mediated by a series of enzymatic reactions that occur on cellular and vascular surfaces. Coagulation proteins circulate in the blood as inactive proteins (zymogens) and upon stimulation are proteolyzed to generate active enzymes. Traditional coagulation models represent the series of reactions as a Y-shaped “cascade” with two upstream separate pathways – the extrinsic and intrinsic pathway – that ultimately converge into a third, final common pathway (Davie and Ratnoff, 1964; Macfarlane, 1964) (Fig. 1). The extrinsic pathway is stimulated when tissue factor (TF) is released and forms a complex with circulating activated factor FVII (FVIIa), while the intrinsic pathway is activated when charged particles (polyphosphates, collagen, etc.) bind and autoactivate factor XII. Thrombin is the final enzyme formed in the coagulation cascade, and the rate of thrombin formation, as well as the amount of thrombin formed directly influences fibrin clot stability and structure (Wolberg, 2007).

Figure 1. Diagram of the enzymatic reactions that mediate blood coagulation.

The clotting factors circulate in an inactive form (zymogen) and are cleaved upon activation to result in a mature enzyme (indicated in bold). Traditionally the cascade is represented as two main pathways (intrinsic pathway, shaded in light grey; and extrinsic pathway, shaded in medium grey) that can be stimulated in vitro with specific proteins or chemicals and merge into a final common pathway (shaded in dark grey). The plasma concentrations of each zymogen are indicated in parentheses.

Inappropriate thrombin generation can result in pathological blood clot formation, termed thrombosis. The treatment of patients with thrombosis almost always includes the administration of an anticoagulant therapeutic to impair procoagulant protein function and prevent blood coagulation. The optimal therapeutic target and the degree of anticoagulation required vary depending on the clinical indication. For example, lower levels of anticoagulation are desired for preventative care in high-risk patients, while potent anticoagulation is required during surgical procedures, such as cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery (also known as open heart surgery), to treat or limit thrombosis.

Genetic studies with knockout mice have been performed to study the role of coagulation proteins and pathway specific responses. However, genetically null mice for TF, factor VII (FVII), factor X (FX), and prothrombin are not viable, making many studies challenging (Mackman, 2005). Therefore, we sought to utilize a set of matched anticoagulant agents to inhibit various human clotting proteins and further clarify the role of these individual proteins in clot formation in human blood. Although small molecule anticoagulants have been generated toward a few coagulation enzymes (i.e., thrombin and activated factor X, abbreviated FXa), it has been challenging to design similar compounds toward the remaining enzymes.

Aptamers, or single-stranded oligonucleotides, are nucleic acid ligands that bind specifically to their therapeutic targets with high affinity. Modified RNA aptamers can be generated against several types of therapeutic targets, including soluble coagulation proteins, by screening combinatorial modified RNA or DNA oligonucleotide libraries for high affinity binding to the target protein (Ellington and Szostak, 1990; Tuerk and Gold, 1990). We have employed this selection method to generate modified RNA aptamers to activated coagulation factor VII (FVIIa) (Layzer and Sullenger, 2007), activated factor IX (FIXa) (Rusconi, et al., 2002), activated factor X (FXa) (Buddai, et al., 2010), and prothrombin (Layzer and Sullenger, 2007). All of the aptamers bind to both the zymogen and enzyme form of their target protein (e.g., FVII and FVIIa), and mechanistic studies with the FIXa, FXa, and prothrombin aptamers indicate that the aptamers bind a large surface area on the zymogen/enzyme that is critical for procoagulant protein-protein interactions (Bompiani, et al., 2012; Buddai, et al., 2010; Sullenger, et al., 2012). Moreover, we have pioneered the development of two independent types of antidotes that can rapidly modulate aptamer anticoagulant function (Oney, et al., 2009; Rusconi, et al., 2002). Currently, an optimized version of our FIXa aptamer and its antidote have completed phase two clinical trials, (Cohen, et al., 2010; Povsic, et al., 2011). Clinical data indicate that this aptamer is potent inhibitor of FIXa function in patients, rapidly anticoagulates subjects within 10 minutes, and can be quickly modulated with its antidote (Chan, et al., 2008; Chan, et al., 2008; Dyke, et al., 2006).

Here we compare the effects of the FVIIa, FIXa, FXa, and prothrombin anticoagulant aptamers in several clotting assays to assess the impact of inhibiting different coagulation factors at different stages and pathways in the coagulation cascade. Additionally, we analyzed the effects of simultaneously inhibiting two proteins within the same or different coagulation pathways by combining two aptamers targeting different factors. Finally, to further explore the clinical potential of these anticoagulant aptamers, we evaluated them in the clinically relevant, highly prothrombotic setting of ex vivo extracorporeal circulation of human blood. We observe that individual aptamers cannot maintain clot-free blood circulation, although a combination of aptamers can. Moreover this combination can be rapidly reversed with antidotes, suggesting that aptamer combinations may have potential clinical utility when rapid and potent anticoagulation is required but safe and rapid reversal of anticoagulation important. Finally, these studies indicate that the availability of collections of aptamers that can potently inhibit individual factors in a branched and interconnected molecular pathway, such as coagulation, allows for detailed functional studies of such complex molecular networks.

RESULTS

Plasma clinical clotting assays (aPTT and PT)

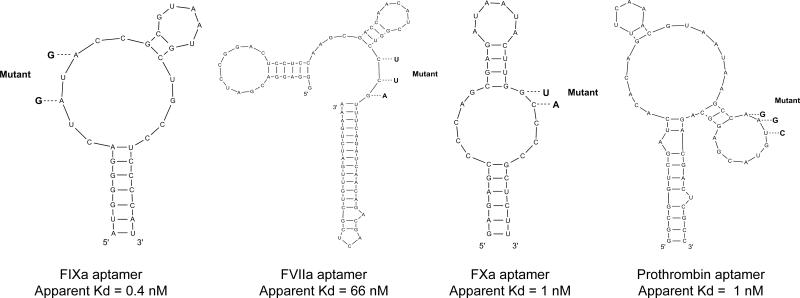

We compared the anticoagulant effects of inhibiting FVIIa (Layzer and Sullenger, 2007), FIXa (Rusconi, et al., 2002), FXa (Buddai, et al., 2010), and prothrombin (Bompiani, et al., 2012) with 2’F-modified RNA aptamers (Fig. 2; for aptamer sequences see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Mechanistic studies have indicated that these aptamers bind with high affinity and selectivity to macromolecular binding sites present on both zymogen and enzyme forms of the individual target proteins and inhibit protein-protein interactions that are essential for coagulation (Bompiani, et al., 2012; Buddai, et al., 2010; Sullenger, et al., 2012).

Figure 2. The M-fold predicted secondary structures of the four modified RNA anticoagulant aptamers and their point mutants.

Point mutants are indicated in bold with dashed lines. The apparent binding affinities of the aptamers are indicated. All four aptamers bind both the zymogen and enzyme form of the clotting factor target.

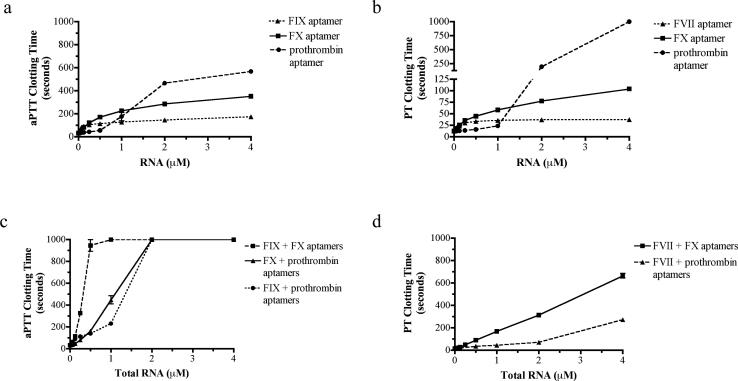

The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) are plasma clotting assays that are clinically used to test for abnormalities in the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways, respectively (Van Cott and Laposata, 2001). These clinical assays measure the time until clot formation in platelet poor plasma stimulated with tissue factor (TF; PT assay for the extrinsic pathway) or the charged particle kaolin (aPTT assay for intrinsic pathway). Although the FXa and prothrombin aptamers can be tested in both the aPTT and PT assays because their targets lie in the common pathway, the FVIIa and FIXa aptamers can only be tested in their respective assay because they target pathway specific enzymes (Fig. 1). Dose titrations with the individual aptamers showed that all of the aptamers produced dose-dependent anticoagulation and prolonged the aPTT and PT clotting time to various degrees (Fig. 3a and b). At saturating concentrations (4 μM), the prothrombin aptamer was the most robust anticoagulant and increased the aPTT clotting time approximately 18-fold and the PT clotting time greater than 80-fold (exceeded the assay limit of 999 seconds). The FXa aptamer was also a robust anticoagulant, and at saturating concentrations (4 μM) it increased the aPTT clotting time approximately 11-fold, and increased the PT clotting time approximately 8-fold. At the same saturating dose, the FIXa aptamer increased the aPTT clotting time approximately 5.5-fold, while the FVIIa aptamer increased the PT clotting time 3-fold (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 3. Dose titrations with each of the four anticoagulant aptamers in clinical aPTT and PT plasma clotting assays.

a) Dose titration response with individual aptamers targeting the intrinsic or common pathway in the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) assay. b) Dose titration response with the individual aptamers targeting the extrinsic or common pathway in the prothrombin time (PT) assay. The data represent the mean ± SEM of duplicates; the lines were arbitrarily drawn. c) Dose titration for combinations of two aptamers in the aPTT assay. d) Dose titration for combinations of two aptamers in the PT assay. The x-axis represents the total RNA concentration, where each aptamer is present in an equimolar concentration. The data represent the mean ± SEM of duplicates; the lines were arbitrarily drawn.

To determine the effect of inhibiting several proteins in the coagulation cascade, combinations of two aptamers were also assessed. Combinations of drugs that inhibit several enzymes within a biological pathway may synergize; that is their combined inhibitory effect may exceed the additive inhibitory effects produced by each inhibitor alone (Berenbaum, 1977). Combinations of two different aptamers at equimolar concentrations were tested in the plasma clot-based assays. At high concentrations (≥1 μM total RNA), all of the aptamer combinations tested in the aPTT assay (i.e., FIXa + FXa, FIXa + prothrombin, and FXa + prothrombin) synergistically prolonged the clotting time and exceeded the assay maximum of 999 seconds (Fig. 3c; for synergy statistical analysis see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Similarly, the FVIIa + FXa combination at high concentrations synergistically prolonged the PT clotting time, and at 4 μM total RNA increased the clotting time approximately 50-fold; however, the FVIIa + prothrombin aptamer combination did not synergistically increase the PT clotting time, and at 4 μM total RNA only increased the clotting time approximately 28-fold (Fig. 3d). Thus, several specific combinations of two anticoagulant aptamers result in a synergistic anticoagulant cocktail that severely retards blood clot formation. Additional dose-scouring studies with varying molar ratios of the aptamers can be performed to optimize dosing based on target plasma concentration.

Thromboelastography (TEG)

Although the aPTT and PT assays provide basic information about dose-dependent anticoagulation, these assays are limited because they are performed in plasma in the absence of platelets. Platelets play a crucial role in clot formation by providing a membrane surface upon which the clotting factors assemble, by aggregating and becoming physically incorporated into the blood clot, and by releasing internal stores of agonists that amplify the coagulation response (Monroe, et al., 2002). Therefore, we studied the effects of factor inhibition with thromboelastography (TEG), which provides information about the kinetics of clot formation in whole blood (Reikvam, et al., 2009). The TEG assay uses mechanical motion to quantify the physical properties of clot formation, including the lag time (the time until clot formation), the α angle (the rate of clot formation), and the maximum amplitude (the mechanical strength of the clot formed) (Fig. S1).

When blood was stimulated with the intrinsic pathway activator kaolin, the FIXa, FXa, and prothrombin aptamers all produced a dose dependent effect and impaired clot formation (Table 1). At a saturating concentration, the FIXa aptamer increased the lag-time, or time to clot initiation (6.9 vs. 25.5 min), decreased the rate of clot formation (α-angle of 62.4 vs. 37.6°), and decreased the maximum clot strength (amplitude of 63.5 vs. 55.4 mm). The FXa aptamer at a saturating concentration had a more robust effect and further increased the lag-time (6.9 vs. 39.6 min), decreased the α-angle (62.4 vs. 18°), and decreased the maximum amplitude (63.5 vs. 39.6 mm). Finally, the prothrombin aptamer at the same concentration increased the lag time to (6.9 vs. 21.5 min), decreased the α-angle to (62.4 vs. 30°), and decreased the maximum amplitude (63.5 vs. 49.6 mm) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Thromboelastography clot formation parameters for whole blood anticoagulated with various individual aptamers and stimulated with either kaolin or Tissue Factor (TF).

| Aptamer | RNA (μM) | Stimulant | Lag time (min) | Angle (deg) | Max. Amplitude (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| none | --- | Kaolin | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 62.4 ± 1.6 | 63.5 ± 0.9 |

| FIXa | 0.5 | Kaolin | 22.8 ± 2.0 | 41.4 ± 0.5 | 55.4 ± 3.2 |

| 1.0 | Kaolin | 25.5 ± 1.8 | 37.6 ± 7.1 | 55.4 ± 2.6 | |

| 2.0 | Kaolin | 29.9 ± 1.4 | 36.9 ± 2.9 | 55.9 ± 3.4 | |

| FXa | 0.5 | Kaolin | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 40.3 ± 1.4 | 52.4 ± 1.6 |

| 1.0 | Kaolin | 20.6 ± 3.0 | 28.7 ± 5.0 | 48.2 ± 3.7 | |

| 2.0 | Kaolin | 39.6 ± 9.1 | 18.0 ± 5.9 | 39.6 ± 4.4 | |

| prothrombin | 1.25 | Kaolin | 7.1 ± 1.4 | 60.4 ± 2.4 | 62.0 ± 3.0 |

| 2.0 | Kaolin | 8.3 ± 2.0 | 48.1 ± 9.7 | 56.0 ± 6.3 | |

| 5.0 | Kaolin | 21.5 ± 4.9 | 30.0 ± 5.7 | 49.6 ± 3.6 | |

| FIXa mutant | 2.0 | Kaolin | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 58.6 ± 7.8 | 60.1 ± 5.8 |

| FXa mutant | 2.0 | Kaolin | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 69.7 ± 1.2 | 65.8 ± 0.8 |

| prothrombin mutant | 5.0 | Kaolin | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 56.0 ± 4.8 | 61.9 ± 4.0 |

| none | ---- | TF | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 65.2 ± 2.4 | 67.8 ± 1.2 |

| FVIIa | 0.12 | TF | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 65.2 ± 5.2 | 63.0 ± 3.7 |

| 0.25 | TF | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 62.4 ± 3.7 | 64.0 ± 2.8 | |

| 0.50 | TF | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 61.9 ± 3.3 | 63.1 ± 2.0 | |

| FIXa | 1.00 | TF | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 66.3 ± 1.3 | 69.1 ± 1.5 |

| FXa | 2.00 | TF | 51.1 ± 12.2 | 21.4 ± 7.3 | 51.1 ± 1.6 |

| prothrombin | 5.00 | TF | 39.4 ± 5.0 | 15.2 ± 2.5 | 36.8 ± 1.4 |

| FIXa mutant | 1.00 | TF | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 69.0 ± 4.8 | 67.2 ± 1.6 |

| FXa mutant | 2.00 | TF | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 68.5 ± 0.5 | 67.9 ± 0.7 |

| prothrombin mutant | 5.00 | TF | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 72.3 ± 0.7 | 66.1 ± 1.4 |

| FVIIa mutant | 0.50 | TF | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 67.8 ± 3.8 | 67.2 ± 0.7 |

The data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with blood from three different healthy donors. TF = tissue factor, min = minutes; deg = degrees; mm = millimeters; max. amplitude = maximum amplitude

Because kaolin stimulates blood via the intrinsic pathway (Fig. 1), it is unlikely that the FVIIa aptamer will impair clot formation with this type of stimulation; thus, we tested this aptamer in a modified TEG with TF stimulation. TF was diluted to a final concentration of 0.33 pM to stimulate clotting, and control baseline assays simulated with TF produced lag times, α angles, and maximum amplitudes comparable to the normal kaolin baseline parameters (Table 1). At a saturating concentration, the FVIIa aptamer slightly increased the lag-time (4.6 vs. 6.6 min), but did not appreciably impact the α-angle (65.2 vs. 61.9) or maximum amplitude (67.8 vs. 63.1 mm) with TF stimulation. A saturating concentration of the FIXa aptamer did not increase the lag time (4.6 vs. 4.5 min), decrease the α-angle (65.2 vs. 66.3°), or the maximum amplitude (67.8 vs. 69.1 mm) with TF stimulation. In contrast, the FXa aptamer at a saturating concentration increased the lag time (4.6 vs. 51.1 min), decreased the α angle (65.2 vs. 21.4°), and decreased the maximum amplitude (67.8 vs. 51.1 mm) (Table 1). Finally, a saturating concentration of the prothrombin aptamer (5 μM) increased the lag time (4.6 vs. 39.4 min), decreased the α-angle (65.2 vs. 15.2°), and decreased the maximum amplitude (67.8 vs. 36.8 mm) in a TF-stimulated TEG (Table 1).

To show that inhibition of thrombin generation requires functional RNA aptamers, we designed and tested point mutant control RNAs. Rusconi et al. showed that mutating two conserved nucleotides completely abolished FIXa aptamer activity, indicating that these nucleotides are crucial for RNA folding and/or protein binding (Rusconi, et al., 2002) (Fig. 2). Similar point mutant controls were also designed for the FXa and prothrombin aptamers and were previously shown to be non-functional in aPTT/PT clotting assays (Bompiani, et al., 2012; Buddai, et al., 2010). Likewise, a FVIIa point mutant was designed that had no significant impact on PT clotting time when tested in parallel with the FVIIa aptamer (data not shown). TEG experiments were performed with these point mutants at the same concentrations as the functional aptamers to show that aptamer anticoagulation is specific and not engendered by high concentrations of modified RNA. As was expected, none of the point mutant control RNAs had an impact on clot formation stimulated by kaolin or TF (Table 1).

Although the individual aptamers slowed clot formation as measured by TEG, no single aptamer prevented clot formation for greater than one hour following either kaolin or TF stimulation. Therefore, we tested the effect of aptamer combinations to see if aptamer combinations exert synergistic inhibitory effects in whole blood. Anticoagulation with aptamer combinations FIXa + FXa, FIXa + prothrombin, and FXa + prothrombin all completely inhibited clot formation by kaolin stimulation for greater than the maximum time of the TEG assay, 3 hours (Table 2). In contrast, the FVIIa + FIXa aptamer combination was not able to prevent clot formation by TF stimulation for greater than 55 minutes, and FVIIa + FXa aptamer anticoagulation only prevented clot formation by TF stimulation for greater than three hours in one of the three donors tested with TF stimulation (Table 2). Control experiments were performed where each functional aptamer was tested in combination with the appropriate point mutant control RNA at the relevant concentrations. As expected, the control combinations did not exhibit synergism and anticoagulated plasma to a degree that was similar to the individual functional aptamers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Thromboelastography clot formation parameters for whole blood anticoagulated with various aptamer combinations and stimulated with kaolin or tissue factor (TF).

| Aptamer 1 | Aptamer 2 | Stimulant | Lag time (min) | Angle (deg) | Max. Amplitude (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | Kaolin | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 60.8 ± 0.4 | 63.8 ± 1.3 |

| None | None | TF | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 65.2 ± 2.4 | 67.8 ± 1.2 |

| FVIIa (0.5 μM) | FIXa (1.0 μM) | TF | 29.7 ± 12.6 | 40.8 ± 9.2 | 60.8 ± 1.5 |

| FVIIa (0.5 μM) | FXa (2.0 μM) | TF | 75.5 ± 2.8* | 8.5 ± 1.5* | 43.2 ± 6.6* |

| FIXa (1.0 μM) | FXa (2.0 μM) | kaolin | No clot formation within 3 hr | ||

| FIXa (1.0 μM) | prothrombin (5.0 μM) | kaolin | No clot formation within 3 hr | ||

| FXa (0.5 μM) | prothrombin (5.0 μM) | kaolin | No clot formation within 3 hr | ||

| FVIIa (0.5 μM) | FIXa mutant (1.0 μM) | TF | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 54.1 ± 4.9 | 67.5 ± 1.5 |

| FXa (2.0 μM) | FVIIa mutant (0.5 μM) | TF | 45.5 ± 11.3 | 23.7 ± 10.1 | 51.7 ± 6.1 |

| FXa (2.0 μM) | FIXa mutant (1.0 μM) | kaolin | 77.8 ± 36.8 | 16.7 ± 11.2 | 31.8 ± 15.4 |

| prothrombin (5.0 μM) | FIXa mutant (1.0 μM) | kaolin | 42.1 ± 1.0 | 17.2 ± 1.4 | 41.6 ± 1.4 |

| FXa (0.5 μM) | prothrombin mutant (5.0 μM) | kaolin | 26.7 ± 5.1 | 34.3 ± 8.9 | 52.2 ± 3.4 |

The data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with blood from three different healthy donors. TF = tissue factor; min = minutes; deg = degrees; mm = millimeters; max. amplitude = maximum amplitude; hr = hours.

Clotting was observed within 3 hours for only two of the three donors; the data represent the mean ± SEM of these two donors.

Extracorporeal circulation

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB, also known as ‘open heart surgery’) is the most prothrombotic setting where rapid onset anticoagulation is often required. During CPB, the patient's blood is removed from the heart and siphoned off into a machine (extracorporeal circuit) that replaces heart and lung function. Potent systemic anticoagulation is required during CPB to maintain blood fluidity in response to numerous stimuli (Levi, et al., 2011; Yavari and Becker, 2008). Unfractionated heparin (UFH), which is a glycosaminoglycan that targets multiple coagulation factors, and its antidote protamine are the current standard of care for CPB anticoagulation. However, both UFH and protamine can cause potentially severe side effects (Carr and Silverman, 1999; Warkentin, 1999).

To determine if inhibition of coagulation factors with aptamers could maintain blood fluidity in this highly procoagulant setting, we performed experiments where human blood was continuously circulated in a miniature model extracorporeal circuit for two hours in the presence of various anticoagulants (de Lange, et al., 2007; de Lange, et al., 2008). The blood is continually circulated from a reservoir to a membrane via a mechanical roller pump, and as the blood is circulated it is heated to approximately 33°C and supplied with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (Fig. S2). The goal of these experiments was to determine if inhibition of individual or sets of coagulation factors with aptamer(s) could maintain human blood fluidity during extracorporeal circulation and successfully replace UFH. Whole human blood was anticoagulated with the aptamers or UFH and circulated in the extracorporeal bypass circuit for two hours or until visible clot formation was observed. At specified time points, blood samples were withdrawn to determine the activated clotting time plus (ACT+) on a point of care device that is utilized to monitor anticoagulant activity during CBP. Similar to the aPTT/PT clotting time assays, the ACT+ assay measures the clotting time; however, the ACT+ assay contains a mixture of activators (silica and kaolin) and measures clotting time in whole blood, rather than platelet poor plasma.

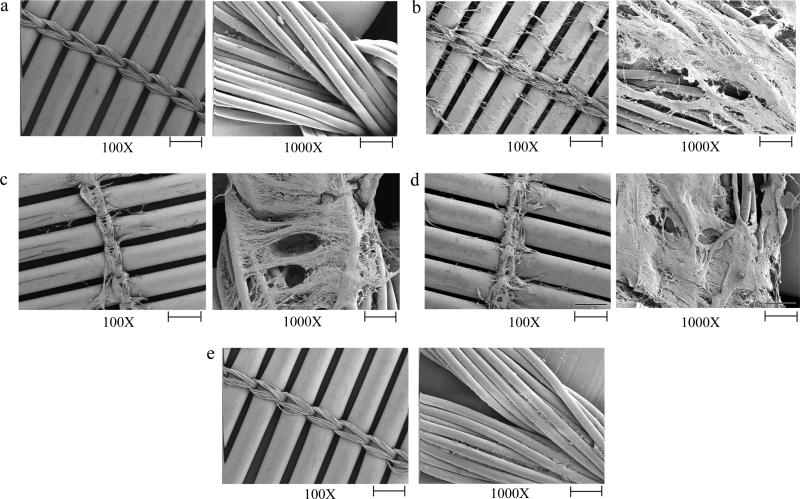

As expected, UFH-mediated anticoagulation (5 U/mL) maintained blood fluidity and circuit patency for 2 hours. The ACT+ clotting time was increased from an average of 124 seconds (average donor baseline) to an average maximal clotting time of 426 seconds (Table S1), which is within the suggested range of 400-480 seconds for CPB (Cohn and Edmunds, 2008). At the end of the two-hour experiment the circuit was flushed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and no visible clotting was observed. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the oxygenator membrane shows that there was no microscopic fibrin deposition and minimal cellular adhesion to the membrane (Fig. 4a; for SEM preparation details see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Figure 4. Scanning electron micrographs of extracorporeal circuit oxygenator membranes from circuits with various anticoagulants.

Micrograph of a membrane from an extracorporeal circuit anticoagulated with a) UFH (5 U/mL), b) FIXa aptamer (1 μM), c) FXa aptamer (2 μM), d) prothrombin aptamer (5 μM), and e) FXa (0.5 μM) + prothrombin aptamers (5 μM). The images are representative of data obtained from three different areas of the membrane. Scale bar: 500 μm (100X) and 50 μm (1000X).

In sharp contrast to UFH, inhibition of no single coagulation factor with an aptamer prevented clot formation in the circuit. Macroscopic clots were formed either within the reservoir, on the oxygenator membrane, or at both sites within 2 hours. Compared to the average donor baseline ACT+ clot time (124 seconds), FIXa aptamer anticoagulation did not increase the clotting time (102 seconds), FXa aptamer anticoagulation increased the ACT+ to a maximum of 213 seconds, and prothrombin aptamer anticoagulation increased the ACT+ to a maximum of 365 seconds (Table S1). Due to its limited impact on thrombin generation in the previous in vitro assays, the FVIIa aptamer was not analyzed ex vivo. Scanning electron micrographs of the oxygenator membrane from circuits anticoagulated with the FIXa, FXa, or prothrombin aptamers show fibrin deposition on the membrane (Fig. 4b, c, and d). Thus, inhibition of individual coagulation factors with the various aptamers does not provide a satisfactory degree of anticoagulation to prevent clot formation in a human extracorporeal circuit.

Because UFH anticoagulates blood by inhibiting several procoagulant enzymes (Bedsted, et al., 2003; Beeler, et al., 1979; Olson, et al., 1992), we hypothesized that combinations of anticoagulant aptamers may more effectively mimic UFH anticoagulation in the ex vivo circuit. The three potent aptamer combinations that kept whole blood fluid in a TEG for greater than three hours (FIXa + FXa, FIXa + prothrombin, and FXa + prothrombin aptamers; Table 2) were tested in the ex vivo circuit. Simultaneous inhibition of FIXa and FXa with aptamers failed to maintain the ex vivo circuit clot-free as macroscopic blood clots in the reservoir and on the oxygenator membrane were apparent after the blood was circulated for two hours. This combination increased the ACT+ from an average baseline of 124 seconds to a maximum of 205 seconds (Table S1). Similarly inhibition of FIXa and prothrombin with this aptamer combination failed to maintain the circuit clot-free as visible blood clots appeared on the oxygenator membrane. This aptamer combination increased the ACT+ clotting to a maximum of 368 seconds (Table S1).

However, inhibition of FXa and prothrombin using an aptamer combination successfully prevented clot formation in the circuit for greater than two hours in three independent experiments with blood from three different donors. This combination prolonged the ACT+ clotting time from an average of 124 seconds to a maximal time of 462 seconds (Table S1). Scanning electron micrographs of the oxygenator membrane from circuits treated with FXa + prothrombin aptamer anticoagulation show minimal fibrin deposition and cellular adhesion, similar to the UFH heparin membrane (Fig. 4e). Thus, simultaneous inhibition of FXa and prothrombin with the combination of FXa and prothrombin aptamers can emulate UFH and robustly anticoagulate human blood during circulation in an extracorporeal bypass circuit.

Antidote reversal of the FXa + prothrombin aptamer combination

We have previously described two independent methods of anticoagulant aptamer control with either a complementary matched oligonucleotide antidote (Rusconi, et al., 2002) or a universal antidote (Oney, et al., 2009). Because our data here show that several aptamer combinations result in extremely robust anticoagulation, we wanted to show that synergistic aptamer combinations can be effectively controlled with an antidote, thereby potentially improving drug safety. Therefore, we tested antidote reversal of the FXa + prothrombin aptamer combination that successfully maintained blood fluidity in the extracorporeal bypass circuit.

Whole blood was anticoagulated with the FXa + prothrombin aptamers at a dose that prevented clot formation for greater than three hours in a TEG, and various antidotes were subsequently added. Both protamine and the β-cyclodextrin containing polymer (CDP) were tested for their ability to function as a universal antidote by simultaneously reversing both aptamers in combination (Oney, et al., 2009). After anticoagulation with the aptamer combination for one hour, addition of a 4-fold molar excess of protamine (22 μM) compared to the aptamers resulted in stable clot formation within an average of 14 minutes, while CDP (50 μg) was even more effective at reversing anticoagulation and resulted in stable clot formation within an average of 11 minutes (Table 3). Additionally, an antidote cocktail containing a 3-fold molar excess of the FXa antidote oligonucleotide and a 2-fold molar excess of the prothrombin antidote oligonucleotide (Bompiani, et al., 2012) reversed anticoagulation and resulted in clot formation within an average of 12 minutes (Table 3). Therefore, aptamer reversal with CDP or antidote oligonucleotides appears to be rapid, as the blood clotted within a similar time frame as blood that has never been anticoagulated (within 8 minutes). Thus, although the FXa + prothrombin aptamer combination is an extremely potent anticoagulant cocktail that can replace UFH anticoagulation in an ex vivo circuit and maintain blood fluidity, the aptamer combination can also be rapidly reversed with either a universal antidote or a combination of oligonucleotide antidotes.

Table 3.

Thromboelastography clot formation parameters for whole blood anticoagulated with the FXa and prothrombin aptamer combination subsequently reversed with either oligonucleotide or universal antidotes.

| Aptamer | Stimulant | Antidote | Lag time (min) | Angle (deg) | Max. Amplitude (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Kaolin | None | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 62.0 ± 0.8 | 65.4 ± 0.35 |

| FXa (0.5 μM) + prothrombin (5 μM) | Kaolin | None | No clot formation within 3 hr | ||

| Protamine (22 μM) | 13.1 ± 1.0 | 47 ± 2.5 | 53.1 ± 1.8 | ||

| CDP (50 μg) | 10.2 ± 1.4 | 53.4 ± 1.8 | 59.7 ± 1.7 | ||

| FXa + prothrombin oligonucleotide antidotes (1.5 μM + 10 μM) | 11.1 ± 1.5 | 52.6 ± 3.5 | 59.6 ± 1.2 | ||

The data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with blood from three different healthy donors. Blood was stimulated with kaolin and anticogulated with 0.5 μM FXa aptamer and 5 μM prothrombin aptamer. Antidotes were added after one hour of anticoagulation, and TEG parameters were measured. min = minutes; deg = degrees; mm = millimeters; max. amplitude = maximum amplitude.

DISCUSSION

The coagulation cascade represents an intricate and critical biological system. Coagulation has been extensively characterized and modeled over the past 100 years and represents an ideal paradigm to study the global effects of perturbing the system in a myriad of ways. Our panel of anticoagulant aptamers represents a valuable tool to study changes in clot formation and thrombin generation when individual or combinations of coagulation enzymes are functionally removed from the system by titrating in the appropriate inhibitory aptamer.

Our data indicate that the individual aptamers each have a unique dose-dependent impact on clot formation in various in vitro assays. Although all of the aptamers specifically bind to their therapeutic target with low-nanomolar affinities (Bompiani, et al., 2012; Buddai, et al., 2010; Layzer and Sullenger, 2007; Sullenger, et al., 2012) (Fig. 2), the in vitro plasma data indicate that to produce optimal anticoagulation, enough aptamer must be added to saturate the protein target in plasma (Fig. 3). For example, although the prothrombin binds to human prothrombin with a Kd of 10 nM, micromolar concentrations are required to saturate prothrombin, which has an estimated concentration of 1.4 μM in human plasma (Bompiani, et al., 2012). Consequentially, lower concentrations of aptamers targeting “upstream” less abundant coagulation factors (i.e., FVII and FIX) are required for saturation compared to aptamers targeting “downstream” more abundant coagulation factors (i.e., FX and prothrombin) (Fig. 1 and 3).

Clinical studies have shown that the FIXa aptamer generates a Hemophilia B-like state by inhibiting greater than 99% of FIXa activity in vivo (Povsic, et al., 2011). Moreover, this aptamer-antidote pair sufficiently anticoagulated blood to allow for neonatal swine to be placed upon cardiopulmonary bypass for up to 60 minutes (Nimjee, et al., 2006), and phase 2b clinical trials indicate that this anticoagulant system can effectively anticoagulate patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, or ‘angioplasty’) (Cohen, et al., 2010). However, our data clearly show that this aptamer has a limited anticoagulant effect in the presence of high TF and may therefore be less effective for treating clinical indications that are associated with high levels of TF (Table 1 and 2). Although it is commonly believed that coagulation is mainly initiated by the contact/intrinsic pathway during extracorporeal circulation (Fuhrer, et al., 1986; Wachtfogel, et al., 1989; Wachtfogel, et al., 1993), several studies have indicated that TF stimulation plays a major role (Boisclair, et al., 1993; Burman, et al., 1994; Kappelmayer, et al., 1993). Correspondingly, the FIXa aptamer was not able to anticoagulate adult human blood during ex vivo extracorporeal circulation for two hours to an extent that maintained the circuit clot free (Fig. 4b) and may therefore not be ideal as a sole anticoagulant for CPB in adult humans.

The impact of inhibiting two specific procoagulant proteases was analyzed by assessing the effect of combining two individual aptamers. Combining two drugs that inhibit proteins within the same pathway has the potential to synergistically inhibit downstream responses (Berenbaum, 1977). Interestingly, although some of the aptamer cocktails resulted in synergistic anticoagulation in vitro, several aptamer combinations were not synergistic (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Generally speaking, aptamer combinations that inhibit two non-sequential enzymatic reactions (i.e., FVIIa + prothrombin) appeared less synergistic compared to combinations that inhibit sequential steps (i.e., FXa + prothrombin). Inhibiting two sequential enzymes may more effectively prevent signal amplification, resulting in more robust anticoagulation.

Bench top clotting assays such as the aPTT/PT are routinely used in the clinic to rapidly assess coagulation deficiencies in patients, where clotting factor deficiencies result in increased clotting times. Similarly, these tests can be applied in a research environment to rapidly assess the function of anticoagulant therapeutics. However, these assays have a number of limitations that should be considered. Plasma-based assays are performed in the absence of platelets, and thus only represent one component of the hemostatic system. Additionally, stimulation with extreme concentrations of TF or artificial agents, such as kaolin, is not representative of clotting activation in vivo. While these assays can be used to monitor anticoagulant function, they are not predictive of function in varying clinical environments. Thus, anticoagulant regimes must be evaluated in experiments closely mimicking their clinical application. As such, we utilized a model of blood circulation to mimic extracorporeal circulation during cardiopulmonary bypass to test one specific clinical application of our technology.

Strikingly, no individual aptamer was able to totally prevent clot formation in the ex vivo circuit for two hours. The current regimen for cardiopulmonary bypass, unfractionated heparin (UFH), anticoagulates blood by inhibiting several coagulation factors (FIXa, FXa, and thrombin) (Bedsted, et al., 2003; Beeler, et al., 1979; Olson, et al., 1992); therefore, we hypothesized that a combination of anticoagulant aptamers may better mimic UFH anticoagulation during CPB. Of the three synergistic aptamer combinations that were tested in the ex vivo circuit, only the FXa + prothrombin aptamer combination was able to totally prevent fibrin deposition on the oxygenator membrane and was comparable to treatment with UFH (Fig. 5e). This aptamer combination may be optimal because it inhibits the two steps in the common pathway of coagulation, rather than pathway specific steps (Fig. 1). Additional studies can be performed to see if adding a third aptamer decreases the doses of aptamers required, or improves other parameters that are clinically relevant during CPB, such as inflammation markers or complement activation.

Although currently a number of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents are available, most of these drugs do not produce an optimal level of anticoagulation for extracorporeal bypass circulation and/or cannot be controlled with an antidote (Murphy and Marymont, 2007). Our data clearly demonstrate that a potent aptamer combination can effectively anticoagulate blood yet be rapidly reversed with several types of antidotes (Table 3). Based upon the ease with which they can used in combination and safely controlled, we believe that aptamers may have broad clinical applications for treating thrombosis in the acute care setting.

SIGNIFICANCE

Coagulation is a concerted series of feed forward and backward enzymatic reactions that has been extensively modeled, although researchers still debate the role of the various enzymes in this interconnected pathway. Knockout mice for several clotting proteins cannot be generated because the proteins are essential for survival, and creation and availability of small molecule drugs for several of these enzymes is beyond most researchers. In contrast, the recent availability of aptamers to an increasing number of proteins led us to explore whether panels of aptamers might represent useful chemical probes to study complex biological pathways, such as blood coagulation. We utilized a set of four aptamers to study the effect of targeting different enzymes involved in coagulation: FVIIa, FIXa, FXa, and prothrombin. Comparative studies with in vitro coagulation assays indicate that each individual aptamer has a particular impact on clot formation, with aptamers targeting ‘downstream’ enzymes (i.e., FXa and prothrombin) engendering more robust anticoagulation.

Inhibiting two proteins within the same biological cascade has the potential to result in synergistic inhibition, and anticoagulants are typically not used in combination because such synergy can lead to uncontrollable bleeding. However, robust anticoagulation is required during some clinical surgical procedures to limit pathological blood clot formation. Several combinations of anticoagulant aptamers act synergistically. The pair of aptamers targeting factor Xa (FXa) and prothrombin can even keep human blood clot-free in the highly procoagulant setting of extracorporeal blood circulation used during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Importantly, the anticoagulant effect of even this potent pair of aptamers could be counteracted by addition of two different types of antidotes to blood, thereby minimizing the risk of excessive bleeding, if needed. Thus, aptamers appear to be useful tools to probe the function(s) of individual and combinations of proteins in biological pathways, such as blood coagulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Normal pooled platelet poor plasma (PPP) was purchased from George King Biomedical. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), tetramethylsilane (TMS), and formaldehyde were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ethanol was purchased from EMD and glutaraldehyde was purchased from TCI America. UFH and protamine sulfate were purchased from APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC. CDP was a generous gift from Jeremy Heidel at Calando Pharmaceuticals. TriniClot aPTT S and TriniClot PT Excel reagents were purchased from Trinity BioTech.

Plasma clotting assays

The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) assays were performed on a model ST4 mechanical coagulometer (Diagnostica Stago) as previously described (Nimjee, et al., 2009). For the aPTT, 50 μL of normal human platelet poor plasma (PPP) was incubated with 50 μL TriniClot aPTT S (Trinity BioTech) at 37°C for 5 min. Aptamer(s) (5 μL) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for another 5 min, and CaCl2 (50 μL) was added to initiate the assay. For the PT, 50 μL of normal human PPP was incubated with 5 μL of aptamer(s) at 37°C for 5 min. TriniClot PT Excel reagent (Trinity BioTech) (100 μL) was added to initiate the reaction. Assays with a combination of two aptamers contain an equimolar concentration of each individual aptamer, and the data shown are the total RNA concentration.

Thromboelastography

Blood was drawn from healthy, consented volunteers under a Duke University Institutional Review Board approved protocol, where blood draw procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines. Blood was anticoagulated with 3.2% sodium citrate, and citrated whole blood (320 μL) was mixed with anticoagulant (heparin or aptamers) (10 μL) and kaolin (Haemonetics) (10 μL) or CAT PRP reagent (Diagnostica Stago, 0.33 ρM TF final) (10 μL) was added to stimulate clotting. CaCl2 (20 μL) was immediately added to overcome the citrate, the mixture was added to a plain disposable plastic TEG cup (Haemonetics), and the assay was run according to the manufacturer's instructions. Clot formation at 37°C was measured with a Thromboelastograph Analyzer (Haemonetics) until a stable clot was formed (i.e., a maximum amplitude was reached) or for three hours with the aptamer combinations. The time lag time, α angle, and maximum amplitude were automatically calculated by the TEG® Analytical Software version 4.2.3 (Haemonetics).

For the antidote reversal TEGs, whole blood was anticoagulated with a combination of the FXa (0.5 μM) and prothrombin (5 μM) aptamers for 1 hour as described, antidote (10 μL) was added, and the assay was continued until a stable clot was formed. At one hour after assay initiation a 4-fold molar excess of protamine (22 μM) was added, 50 μg of CDP was added, or a 2-fold molar excess of the prothrombin aptamer antidote oligonucleotide (10 μM) in combination with a 3-fold molar excess of the FXa aptamer antidote oligonucleotide (1.5 μM) was added.

Extracorporeal membrane circuit oxygenation

The extracorporeal circuit consisted of a sample line, custom-designed 8 mL Plexiglas® venous reservoir, a mechanical roller pump (MasterFlex®; Cole-Parmer Instrument Co.), and a custom-designed small-volume oxygenator that are all connected by MasterFlex precision silicone tubing (Cole-Parmer Instrument Co.)(de Lange, et al., 2007; de Lange, et al., 2008). The 4 mL priming volume oxygenator is comprised of two Plexiglas® shells (12.8 cm × 12.8 cm × 2.7 cm) that cover a disposable three layer artificial diffusion membrane comprised of hollow polypropylene fibers glued together in a crosswise fashion. The surface area available for gas exchange is 558 cm2. To prevent heat loss, one of the shells has an integrated heat exchanger, and the temperature was maintained at approximately 33°C with a circulating water bath system (Gaymar Industries). A MEAS reusable temperature probe (Model 451, Measurement Specialties Inc.) was inserted into the reservoir to continuously measure the temperature, and an in-line flow probe (2N806 flow probe and T208 volume flowmeter; Transonics Systems, Inc.) was used to continuously measure the blood flow. The circuit blood O2 level was maintained at 95% and the CO2 was maintained at 5%.

The circuit was primed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a flow rate of 50 mL/min for approximately 30 minutes. Blood was drawn from healthy, consented volunteers under a Duke University Institutional Review Board approved protocol, where blood draw procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines. The blood was anticoagulated with 3.2% sodium citrate, and approximately 25 mL of citrated blood was incubated with 500 μL of anticoagulant (i.e., UFH or aptamer) at 37°C for 5 min. The PBS was drained from the circuit, and the blood was added and circulated at a rate of 50 mL/min with 95% O2/5% CO2 at approximately 33°C. CaCl2 (660 μL, 6.45 mM final) was added to overcome the citrate and initiate the experiment. Blood samples (~200 μL) were withdrawn from the baseline citrated blood (no aptamer) and from the circuit reservoir at 5, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min post circuit initiation, or until visible clot formation. ACT+ assays (ITC) were immediately run with a Hemochron Jr. signature point of care device (ITC Nexus Dx). To analyze the citrated baseline ACT+ values, 6.45 mM CaCl2 was added to approximately 100 μL of blood, the mixture was incubated for 30 seconds at ambient temperature, and the assay was run according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Inhibitory aptamers can be used to study enzymes in molecular clotting pathways

Inhibiting different steps in coagulation causes various degrees of anticoagulation

Combinations of anticoagulant aptamers are synergistic inhibitors of coagulation

Even potent aptamer combinations can be controlled with antidotes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank M. Gignac for help with the scanning electron microscopy, and M. Qing for help with the extracorporeal circuit setup. Finally, we would like to thank M. Hoffman, D. Monroe, and G. Arepally for helpful discussion. This study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant to B. Sullenger (R01HL65222) and an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship to K. Bompiani (10PRE3260011). B. Sullenger is the scientific founder of Regado Biosciences, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental data: Supplemental data including Supplemental Experimental Procedures, two figures, and one table can be found with this article online at.

REFERENCES

- Bedsted T, Swanson R, Chuang YJ, Bock PE, Bjork I, Olson ST. Heparin and calcium ions dramatically enhance antithrombin reactivity with factor IXa by generating new interaction exosites. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2003;42:8143–8152. doi: 10.1021/bi034363y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler D, Rosenberg R, Jordan R. Fractionation of low molecular weight heparin species and their interaction with antithrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:2902–2913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum MC. Synergy, additivism and antagonism in immunosuppression. A critical review. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1977;28:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisclair MD, Lane DA, Philippou H, Esnouf MP, Sheikh S, Hunt B, Smith KJ. Mechanisms of thrombin generation during surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood. 1993;82:3350–3357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompiani KM, Monroe DM, Church FC, Sullenger BA. A high affinity, antidote-controllable prothrombin and thrombin-binding RNA aptamer inhibits thrombin generation and thrombin activity. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;10:870–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddai SK, Layzer JM, Lu G, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA, Monroe DM, Krishnaswamy S. An anticoagulant RNA aptamer that inhibits proteinase-cofactor interactions within prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:5212–5223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddai SK, Layzer JM, Lu G, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA, Monroe DM, Krishnaswamy S. An anticoagulant RNA aptamer that inhibits proteinase-cofactor interactions within prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:5212–5223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman JF, Chung HI, Lane DA, Philippou H, Adami A, Lincoln JC. Role of factor XII in thrombin generation and fibrinolysis during cardiopulmonary bypass. Lancet. 1994;344:1192–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JA, Silverman N. The heparin-protamine interaction. A review. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) 1999;40:659–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MY, Cohen MG, Dyke CK, Myles SK, Aberle LG, Lin M, Walder J, Steinhubl SR, Gilchrist IC, Kleiman NS, et al. Phase 1b randomized study of antidote-controlled modulation of factor IXa activity in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2865–2874. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.745687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MY, Rusconi CP, Alexander JH, Tonkens RM, Harrington RA, Becker RC. A randomized, repeat-dose, pharmacodynamic and safety study of an antidote-controlled factor IXa inhibitor. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;6:789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MG, Purdy DA, Rossi JS, Grinfeld LR, Myles SK, Aberle LH, Greenbaum AB, Fry E, Chan MY, Tonkens RM, et al. First clinical application of an actively reversible direct factor IXa inhibitor as an anticoagulation strategy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2010;122:614–622. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LH, Edmunds LH. Cardiac surgery in the adult. McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davie EW, Ratnoff OD. Waterfall Sequence for Intrinsic Blood Clotting. Science. 1964;145:1310–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3638.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange F, Dieleman JM, Jungwirth B, Kalkman CJ. Effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on neurocognitive performance and cytokine release in old and diabetic rats. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007;99:177–183. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange F, Yoshitani K, Podgoreanu MV, Grocott HP, Mackensen GB. A novel survival model of cardioplegic arrest and cardiopulmonary bypass in rats: a methodology paper. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008;3:51. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-3-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyke CK, Steinhubl SR, Kleiman NS, Cannon RO, Aberle LG, Lin M, Myles SK, Melloni C, Harrington RA, Alexander JH, et al. First-in-human experience of an antidote-controlled anticoagulant using RNA aptamer technology: a phase 1a pharmacodynamic evaluation of a drug-antidote pair for the controlled regulation of factor IXa activity. Circulation. 2006;114:2490–2497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington AD, Szostak JW. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer G, Gallimore MJ, Heller W, Hoffmeister HE. Studies on components of the plasma kallikrein-kinin system in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1986;198(Pt B):385–391. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0154-8_49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappelmayer J, Bernabei A, Edmunds LH, Jr., Edgington TS, Colman RW. Tissue factor is expressed on monocytes during simulated extracorporeal circulation. Circul. Res. 1993;72:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layzer JM, Sullenger BA. Simultaneous generation of aptamers to multiple gamma-carboxyglutamic acid proteins from a focused aptamer library using DeSELEX and convergent selection. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, Eerenberg E, Kamphuisen PW. Bleeding risk and reversal strategies for old and new anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1705–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane RG. An Enzyme Cascade in the Blood Clotting Mechanism, and Its Function as a Biochemical Amplifier. Nature. 1964;202:498–499. doi: 10.1038/202498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman N. Tissue-specific hemostasis in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005;25:2273–2281. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000183884.06371.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe DM, Hoffman M, Roberts HR. Platelets and thrombin generation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:1381–1389. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000031340.68494.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GS, Marymont JH. Alternative anticoagulation management strategies for the patient with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia undergoing cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2007;21:113–126. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee SM, Keys JR, Pitoc GA, Quick G, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA. A novel antidote-controlled anticoagulant reduces thrombin generation and inflammation and improves cardiac function in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee SM, Oney S, Volovyk Z, Bompiani KM, Long SB, Hoffman M, Sullenger BA. Synergistic effect of aptamers that inhibit exosites 1 and 2 on thrombin. RNA. 2009;15:2105–2111. doi: 10.1261/rna.1240109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson ST, Bjork I, Sheffer R, Craig PA, Shore JD, Choay J. Role of the antithrombin-binding pentasaccharide in heparin acceleration of antithrombin-proteinase reactions. Resolution of the antithrombin conformational change contribution to heparin rate enhancement. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12528–12538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oney S, Lam RT, Bompiani KM, Blake CM, Quick G, Heidel JD, Liu JY, Mack BC, Davis ME, Leong KW, et al. Development of universal antidotes to control aptamer activity. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/nm.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oney S, Lam RT, Bompiani KM, Blake CM, Quick G, Heidel JD, Liu JY, Mack BC, Davis ME, Leong KW, et al. Development of universal antidotes to control aptamer activity. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/nm.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povsic TJ, Wargin WA, Alexander JH, Krasnow J, Krolick M, Cohen MG, Mehran R, Buller CE, Bode C, Zelenkofske SL, et al. Pegnivacogin results in near complete FIX inhibition in acute coronary syndrome patients: RADAR pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic substudy. Eur. Heart J. 2011;32:2412–2419. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reikvam H, Steien E, Hauge B, Liseth K, Hagen KG, Storkson R, Hervig T. Thrombelastography. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2009;40:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi CP, Scardino E, Layzer J, Pitoc GA, Ortel TL, Monroe D, Sullenger BA. RNA aptamers as reversible antagonists of coagulation factor IXa. Nature. 2002;419:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullenger B, Woodruff R, Monroe DM. Potent anticoagulant aptamer directed against factor IXa blocks macromolecular substrate interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:12779–12786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.300772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C, Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cott E, Laposata M. Coagulation. Lexi-Comp; Cleveland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wachtfogel YT, Harpel PC, Edmunds LH, Jr., Colman RW. Formation of C1s-C1-inhibitor, kallikrein-C1-inhibitor, and plasmin-alpha 2-plasmin-inhibitor complexes during cardiopulmonary bypass. Blood. 1989;73:468–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtfogel YT, Kucich U, Hack CE, Gluszko P, Niewiarowski S, Colman RW, Edmunds LH., Jr. Aprotinin inhibits the contact, neutrophil, and platelet activation systems during simulated extracorporeal perfusion. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1993;106:1–9. discussion 9-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warkentin TE. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a clinicopathologic syndrome. Thromb. Haemost. 1999;82:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolberg AS. Thrombin generation and fibrin clot structure. Blood Rev. 2007;21:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavari M, Becker RC. Anticoagulant therapy during cardiopulmonary bypass. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2008;26:218–228. doi: 10.1007/s11239-008-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.