Opsismodysplasia (OMIM258480) is a rare, autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia with delayed bone maturation. It was first described in 1977 by Zonana et al. and named opsismodysplasia by Maroteaux et al. in 1984 [Maroteaux et al., 1982; Maroteaux et al., 1984]. The clinical features include micromelia with extremely short hands and feet, as well as facial dysmorphism including prominent eyebrows, large open fontanels, depressed nasal bridge, short anteverted nose and relatively long philtrum. Some patients were also reported as having severe renal phosphate wasting [Below et al., 2013]. The characteristic radiographic features include severe platyspondyly, shortened long bones with dramatically delayed epiphyseal ossification, and characteristic hands with markedly delayed carpal ossification, short squared metacarpals and phalanges, and metaphyseal cupping [Beemer and Kozlowski 1994; Cormier-Daire et al., 2003; Maroteaux et al., 1984; Santos and Saraiva 1995; Tyler et al., 1999; Zonana et al., 1977]. The mortality is highly variable, ranging from death secondary to respiratory failure during the first few years of life to survival into adulthood.

Mutations in INPPL1 (also known as SHIP2; RefSeq accession number NM_001567.3) encoding inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 were found to be a cause of opsismodysplasia [Below et al., 2013; Huber et al., 2013]. By linkage analysis and exome sequencing, Below et al. identified homozygosity for an INPPL1 missense mutation in one of two siblings with opsismodysplasia. Subsequent screening of INPPL1 in ten additional unrelated families with opsismodysplasia identified INPPL1 mutations in half of the cases [Below et al., 2013]. In an independent study, Huber et al. identified 12 distinct INPPL1 mutations in 10 families [Huber et al., 2013]. Subsequently, Iida et al. reported homozygosity for an INPPL1 in-frame deletion in a Japanese family [Iida et al., 2013].

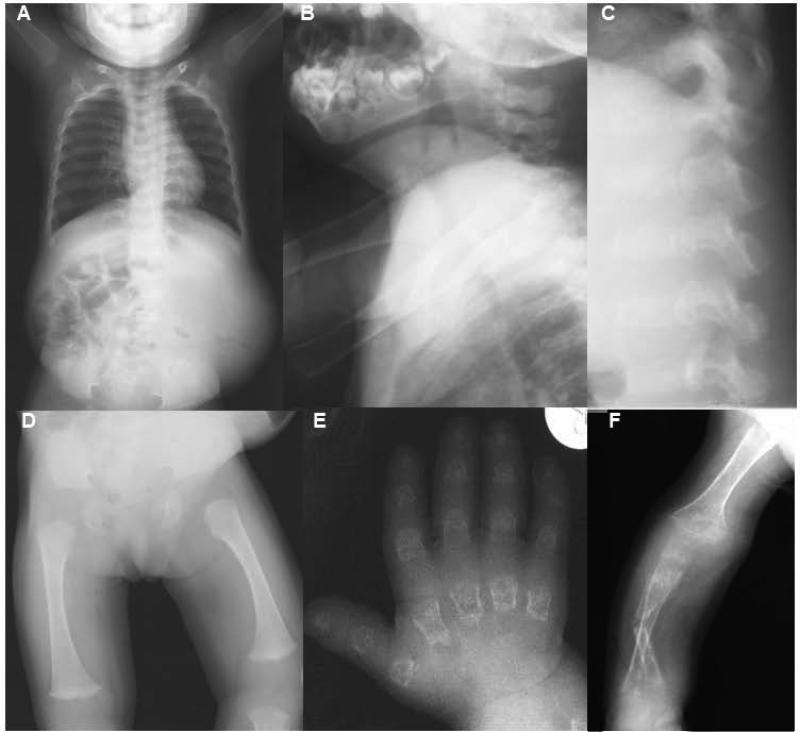

We studied a consanguineous family (International Skeletal Dysplasia Reference number R00-216), originally reported by Bülbül et al. in 2005, in which one of four siblings had opsismodysplasia [Bülbül et al., 2005]. The proband was a girl born at 29 weeks gestation with a birth weight of 1950 g. Short stature, short fingers, limited extension of elbows, absence of eyebrows, eyelashes and nails were observed at birth. At 21 months of age, disproportionate short stature and growth retardation were more prominent. She achieved neuromotor developmental milestones late. Although she started walking at the age of two, she stopped walking at 2 ½ years and became non-ambulatory. She had wide open anterior fontanelles which closed at six years of age. At the age of seven her weight was 9600 g, height 78 cm, span 60 cm and OFC 48 cm. She had facial dysmorphism, prominent forehead, depressed nasal bridge, small bulbous nose, low set, simple ears, high-arched palate, multiple caries, and delayed eruption of permanent teeth. Short and bowed extremities, short hands, feet, fingers and toes, and a small thorax with a relatively prominent abdomen were noted (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2A). Mild hypotonia and diminished deep tendon reflexes were also observed. At 7 years of age renal phosphate wasting with a tubular phosphate reabsorption of 66% (normal value > 95%) was measured. Radiographs were typical for opsismodysplasia, revealing delayed epiphyseal ossification, generalized undermineralization of the skeleton, platyspondyly, metaphyseal cupping and shortened long bones, metacarpals and phalanges, no ossification of carpal bones, and fractures of the radius and fibulae (Fig. 2). After a 6 month course of phosphate replacement she was able to walk again and her deciduous teeth erupted. Because of low bone mineral density (Z score = -6.2; bone density 0.047 gr/m2), pamidronate therapy was initiated. She had a normal pubertal growth spurt and menarche at 15 years of age. Her final height, measured at 21 years of age, was 101 cm.

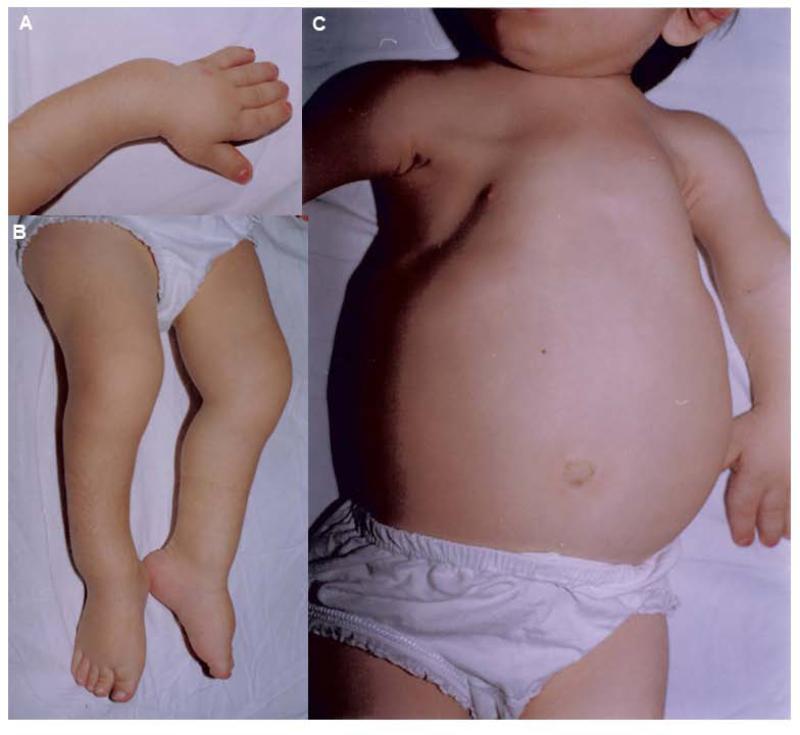

FIG. 1.

Characteristic clinical features of the patient at 7 years of age. The abnormalities included (A) Short hands, fingers and bowing of the upper limbs, (B) Bowing of lower limbs, and (C) Small thorax with a distended abdomen.

FIG. 2.

Radiographs of the patient at 21 months (A-C) and 7 years (D-F) of age. (A) Anterior-posterior (AP) image showing a small thorax and small, rounded pelvis. (B and C) Lateral view of neck and spine showing platyspondyly with under mineralization of the cervical (B) and lumbar (C) vertebrae. (D) AP view of the femur showing severe epiphyseal delay of the capital femoral epiphysis and flared metaphyses of the distal femur. (E) AP view of the hand showing characteristically short and irregular metacarpals and phalanges with severely reduced carpal ossification and osteoporosis. (F) AP view of an upper extremity showing a fractured radius and generalized undermineralization of the upper limb.

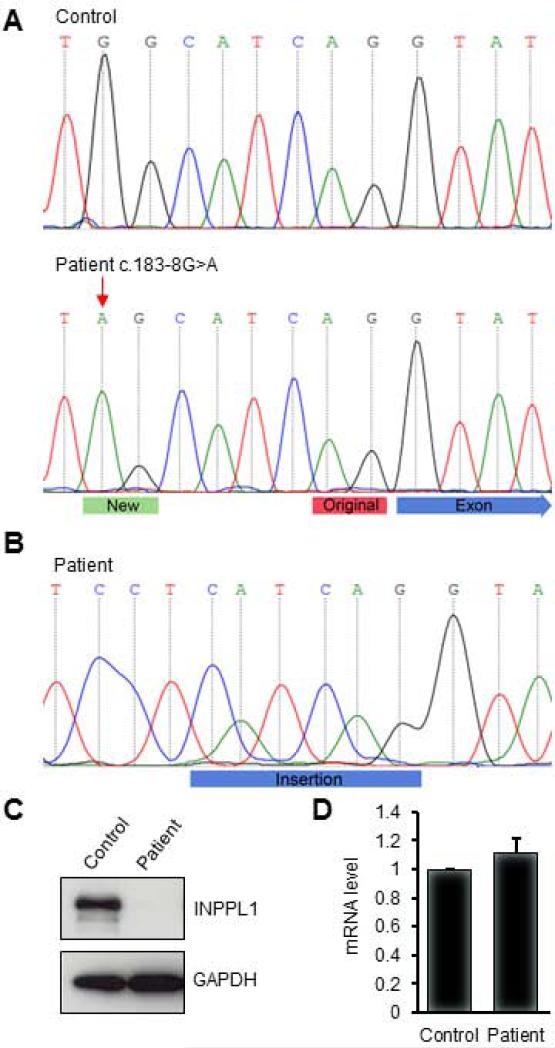

By exome sequencing, homozygosity for a variant (c.183-8G>A) in the first intron of INPPL1 located 8 bp upstream of exon 2 was identified. The nucleotide change was not found in public SNP databases, indicating that it was unique to the family (Fig.3A). Genotyping of the parents and two unaffected siblings showed that all of them were heterozygous for the sequence change (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Change of splicing acceptor site and destabilization of INPPL1 protein by homozygosity for a mutation in INPPL1. (A) Electropherogram representation of genomic DNA fragments spanning the intron 1-exon 2 junction from a control (top panel) and the patient (bottom panel). The c.183-8G>A mutation is indicated by a red arrow. The new splice acceptor created by the mutation is labeled with a green bar. The original splice acceptor is labeled with a red bar. The blue arrow indicates the beginning of exon 2. (B) The mutation leads to a six nucleotide insertion in the INPPL1 cDNA. The blue bar indicates the insertion. (C) Western blotting of INPPL1 protein in a lymphoblastoid cell line from a control and the patient. (D) Detection of INPPL1 mRNA by quantitative PCR. Data were collected from three replicates and are shown as mean +/− standard deviation.

Since the RNA splice acceptor sites at 3’ ends of introns usually terminate with an AG sequence, the creation of a new AG sequence by the variant (see Fig. 3A) suggested that it might form a new splice acceptor site, leading to the insertion of 6 nucleotides into the mRNA transcript. To test this possibility, RT-PCR for the INPPL1 gene using total RNA extracted from a lymphoblastoid cell line derived from patient lymphocytes was performed and the sequence of the PCR product was determined. As shown in Fig.3B, the predicted 6 nucleotide (5’-CATCAG-3’) in-frame insertion was identified between the normal sequences of exons 1 and 2, confirming use of a new splice acceptor in the cultured cells (Fig. 3B). Control mRNA from lymphoblastoid cells derived from an unaffected individual did not contain the insertion (data not shown). At the protein level, the new sequence implies insertion of an Ile-Arg dipeptide into the the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain between Leu61 and Tyr62. Since the SH2 domains specifically recognize phosphotyrosine residues and mediates the interaction of INPPL1 with other proteins [Koch et al., 2005; Prasad et al., 2001], we considered the possibilities that the SH2 domain insertion could affect protein stability by altering protein structure or could change protein-protein interactions if the mutant protein were stable. To distinguish these possibilities, the INPPL1 protein level in the patient's lymphocytes by western blotting was measured. As shown in Fig. 3C, compared with the unaffected control, the INPPL1 protein was barely detectable in patient cells. To determine whether the reduction in protein level was due to transcriptional repression or mRNA destabilization, INPPL1 mRNA level by quantitative real-time PCR was measured. As showed in Fig. 3D, the level of INPPL1 mRNA from the control and patient were indistinguishable, indicating that the transcript was stable and suggesting that the insertion destabilizes INPPL1 at the protein level.

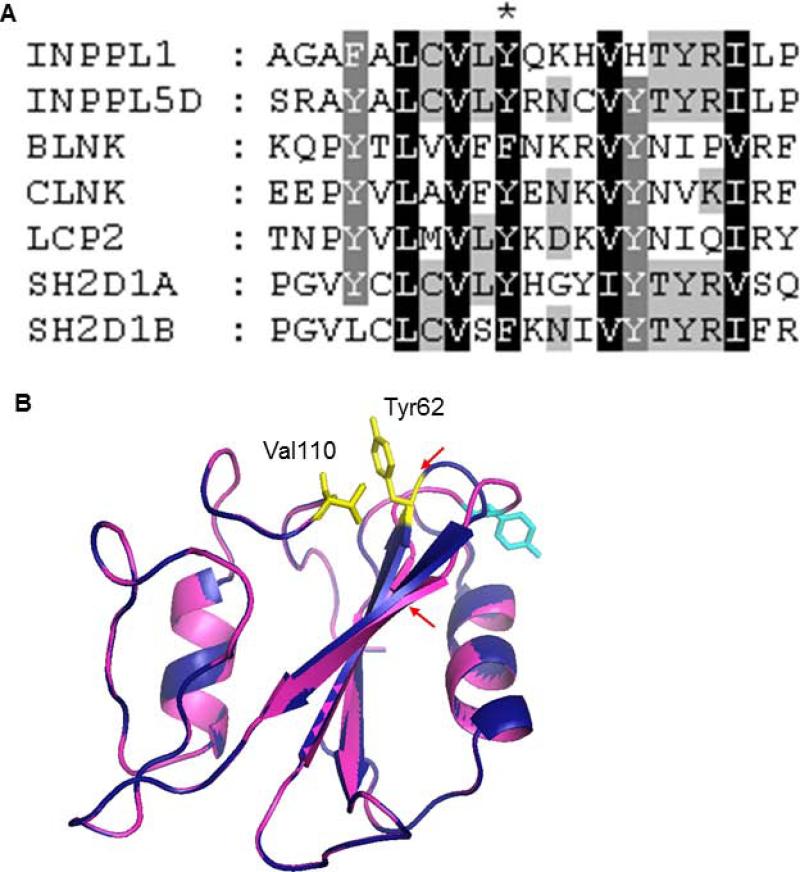

The region of INPPL1 containing the insertion is conserved among members of the SH2 domain-containing protein subfamily that includes INPPL1 [Liu et al., 2006], with multiple invariant positions, suggesting that the altered structure of the domain resulted in protein instability (Fig. 4A). To explore the effect of the insertion on the protein structure, three-dimensional (3D) structural models of the wild-type and mutant INPPL1 SH2 domains were built by protein structure homology modeling using the Swiss-model server and compared [Arnold et al., 2006]. We used the structure of the INPP5D SH2 domain (PDB accession code 2YSX) as the template since it is a homolog of INPPL1 and their SH2 domains are 72% similar. As shown in Fig. 4B, the modeled wild-type INPPL1-SH2 structure has a typical SH2 fold, which includes a central β sheet with two α helices packed against either side [Kuriyan and Cowburn, 1997]. The insertion mutation altered a loop region that normally connects two β strands, leading to expansion of the loop and a predicted decrease in the length of both β strands. The insertion was also predicted to shift the highly conserved hydrophobic Tyr62 residue to the surface of the protein and thereby disrupt the interaction between Tyr62 and Val110. The loss or weakening of this interaction might increase the flexibility of the loop and lead to the destabilization of the protein structure, which could be the cause of reduced cellular INPPL1 protein.

FIG. 4.

Effect of the insertion on INPPL1-SH2 domain structure. (A) Sequence alignment of SH2 domain-containing proteins by ClustalW. Tyr62 in INPPL1 is labeled with an asterisk. (B) Superimposed 3D structures of wild-type and mutant INPPL1 SH2 domains. The wild-type and mutant proteins were colored in deep blue and magenta, respectively. The β strands with reduced length are indicated by red arrows. Tyr62 and Val110 in wild-type protein were colored yellow. The shifted Tyr residue in the mutant protein is colored in cyan.

The role of INPPL1 in endochondral ossification is unknown. The protein belongs to the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase family and regulates phosphoinositides through dephosphorylation of phosphatidlylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate (PtdIns(3,4)P2). PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is an important second messenger that regulates multiple cellular functions such as cell survival, proliferation, adhesion, migration, glucose metabolism and insulin signaling [Riehle et al., 2013]. In mice, depletion of Inppl1 protein by gene targeting lead to resistant to weight gain when placed on a high-fat diet, indicating it mediates obesity resistance. The knockout mice also had developmental defects including significant reduced body length and a shortened facial profile, suggesting effects on both the axial and appendicular skeleton [Sleeman et al., 2005]. Similarly, knockout mice carrying catalytically-inactive Inppl1 protein also showed decreased body length, a shortened snout and a round skull, indicating that Inppl1 catalytic activity is critical for normal bone development [Dubois et al., 2012]. How INPPL1 affects the ossification process through regulation of cellular level of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3/PtdIns(3,4)P2 and their downstream signaling pathways will be an interesting topic for future studies.

In summary, we have identified homozygosity for a point mutation in INPPL1 intron 1 in an opsismodysplasia patient. The mutation resulted in creating of a new splice acceptor insertion of an Ile-Arg dipeptide into the SH2 domain of the protein, leading to a dramatic decrease in the level of INPPL1 protein. The 3D structure model suggests that instability of the protein resulted from alteration of the structure of the SH2 domain, ultimately leading to reduced or absent INPPL1 activity. These data provide further support for and a distinct mechanism by which INPPL1 mutations cause opsismodysplasia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the family for their participation. The authors have no conflicts of interest. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DE019567, AR062651 and 1U54HG006493) and funds from the Orthopaedic Hospital Research Center.

REFERENCES

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beemer FA, Kozlowski KS. Additional case of opsismodysplasia supporting autosomal recessive inheritance. American journal of medical genetics. 1994;49(3):344–347. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320490321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Below JE, Earl DL, Shively KM, McMillin MJ, Smith JD, Turner EH, Stephan MJ, Al-Gazali LI, Hertecant JL, Chitayat D, Unger S, Cohn DH, Krakow D, Swanson JM, Faustman EM, Shendure J, Nickerson DA, Bamshad MJ, University of Washington Center for Mendelian G Whole-genome analysis reveals that mutations in inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 cause opsismodysplasia. American journal of human genetics. 2013;92(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bülbül A, Kayserili H, Bilge I, Saka N, Apak MY, Darendeliler F. Opsismodisplazi ve tubülopati birlikteliği: Bir vaka takdimi. Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları Dergisi. 2005;48(3):242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier-Daire V, Delezoide AL, Philip N, Marcorelles P, Casas K, Hillion Y, Faivre L, Rimoin DL, Munnich A, Maroteaux P, Le Merrer M. Clinical, radiological, and chondro-osseous findings in opsismodysplasia: survey of a series of 12 unreported cases. Journal of medical genetics. 2003;40(3):195–200. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois E, Jacoby M, Blockmans M, Pernot E, Schiffmann SN, Foukas LC, Henquin JC, Vanhaesebroeck B, Erneux C, Schurmans S. Developmental defects and rescue from glucose intolerance of a catalytically-inactive novel Ship2 mutant mouse. Cellular signalling. 2012;24(11):1971–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C, Faqeih EA, Bartholdi D, Bole-Feysot C, Borochowitz Z, Cavalcanti DP, Frigo A, Nitschke P, Roume J, Santos HG, Shalev SA, Superti-Furga A, Delezoide AL, Le Merrer M, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. Exome sequencing identifies INPPL1 mutations as a cause of opsismodysplasia. American journal of human genetics. 2013;92(1):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida A, Okamoto N, Miyake N, Nishimura G, Minami S, Sugimoto T, Nakashima M, Tsurusaki Y, Saitsu H, Shiina M, Ogata K, Watanabe S, Ohashi H, Matsumoto N, Ikegawa S. Exome sequencing identifies a novel INPPL1 mutation in opsismodysplasia. Journal of human genetics. 2013;58(6):391–394. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A, Mancini A, El Bounkari O, Tamura T. The SH2-domian-containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP)-2 binds to c-Met directly via tyrosine residue 1356 and involves hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced lamellipodium formation, cell scattering and cell spreading. Oncogene. 2005;24(21):3436–3447. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan J, Cowburn D. Modular peptide recognition domains in eukaryotic signaling. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure. 1997;26:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BA, Jablonowski K, Raina M, Arce M, Pawson T, Nash PD. The human and mouse complement of SH2 domain proteins-establishing the boundaries of phosphotyrosine signaling. Molecular cell. 2006;22(6):851–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux P, Stanescu V, Stanescu R. Four recently described osteochondrodysplasias. Progress in clinical and biological research. 1982;104:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux P, Stanescu V, Stanescu R, Le Marec B, Moraine C, Lejarraga H. Opsismodysplasia: a new type of chondrodysplasia with predominant involvement of the bones of the hand and the vertebrae. American journal of medical genetics. 1984;19(1):171–182. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320190117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad N, Topping RS, Decker SJ. SH2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase SHIP2 associates with the p130(Cas) adapter protein and regulates cellular adhesion and spreading. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21(4):1416–1428. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1416-1428.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehle RD, Cornea S, Degterev A. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in cell signaling. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2013;991:105–139. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6331-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos HG, Saraiva JM. Opsismodysplasia: another case and literature review. Clinical dysmorphology. 1995;4(3):222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman MW, Wortley KE, Lai KM, Gowen LC, Kintner J, Kline WO, Garcia K, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ, Glass DJ. Absence of the lipid phosphatase SHIP2 confers resistance to dietary obesity. Nature medicine. 2005;11(2):199–205. doi: 10.1038/nm1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler K, Sarioglu N, Kunze J. Five familial cases of opsismodysplasia substantiate the hypothesis of autosomal recessive inheritance. American journal of medical genetics. 1999;83(1):47–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990305)83:1<47::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonana J, Rimoin DL, Lachman RS, Cohen AH. A unique chondrodysplasia secondary to a defect in chondroosseous transformation. Birth defects original article series. 1977;13(3D):155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]