Abstract

Aim

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on maintenance dialysis have a high burden of coronary disease. Prior studies in non-dialysis patients show better outcomes in coronary artery bypass surgery using the internal mammary artery (IMA) compared with the saphenous vein graft (SVG), but less is known about outcomes in ESRD. We sought to compare the effectiveness of multivessel bypass grafting using IMA versus SVG in patients on maintenance dialysis in the United States.

Methods

Cohort study using data from the United States Renal Data System to examine IMA versus SVG in patients on maintenance dialysis undergoing multivessel coronary revascularization. We used Cox proportional hazards regression with multivariable adjustment in the full cohort and in a propensity-score matched cohort. The primary outcome was death from any cause; the secondary outcome was a composite of non-fatal myocardial infarction or death.

Results

Overall survival rates were low in this patient population (5-year survival in the matched cohort 25.3%). Use of the IMA compared to SVG was associated with lower risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84-0.92) and lower risk of the composite outcome (adjusted HR 0.89; CI 0.85-0.93). Results did not materially change in analyses using the propensity-score matched cohort. We found similar results irrespective of patient sex, age, race, or the presence of diabetes, peripheral vascular disease or heart failure.

Conclusion

Although overall survival rates were low, IMA was associated with lower risk of mortality and cardiovascular morbidity compared to SVG in patients on dialysis.

Keywords: Coronary artery bypass grafts, CABG; CABG, arterial grafts; CABG, venous grafts; kidney; outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on maintenance dialysis have an exceptionally high burden of multivessel coronary artery disease, and cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in this patient population 1. Coronary artery disease is often treated surgically with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) using healthy portions of the internal mammary artery (IMA) or a saphenous vein graft (SVG) to bypass diseased portions of vessels. Several observational studies and a single randomized trial have shown improved long-term graft patency and survival in non-dialysis patients with CABG using the IMA compared to SVG 2-7.

Although CABG is often performed in patients on dialysis 8-10, none of the previous studies examining IMA versus SVG included patients with ESRD. In light of the high annual mortality rates 11 in patients on dialysis, the potential advantages of better long-term graft patency with an IMA may be less important. Use of the IMA can have higher short-term risks in patients on dialysis, with the dialysis procedure causing reduced flow through the IMA and symptomatic angina in some cases 12-15. Moreover, the underlying biology and patterns of coronary artery disease differ among patients with ESRD and patients without kidney disease 1,16. Therefore, the comparative effectiveness of IMA versus SVG in patients with ESRD on dialysis undergoing CABG may differ from the non-ESRD population. We tested the hypothesis that CABG using IMA would be associated with lower risks of long-term mortality and cardiovascular morbidity compared with SVG alone in patients with ESRD on maintenance dialysis in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

The United States Renal Data System (USRDS) provides comprehensive administrative records for over 95% of ESRD patients in the United States 11. We used a previously assembled cohort of patients on maintenance dialysis undergoing first coronary revascularization for multivessel disease between 1997 and 2009 10. Briefly, we analyzed the subset of patients undergoing CABG (excluding patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention), identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, procedure codes 36.12, 36.13, 36.14, or 36.16. Patients were excluded if they underwent concomitant cardiac or valve surgery (procedure codes 35.xx, 37.31, 37.32, 37.35, 37.4, 37.5). The use of IMA was identified as procedure code of 36.15 or 36.16; patients without these codes were categorized as having received only SVG 17. We required at least 6 months of continuous Medicare Part A and Part B coverage as the primary payer prior to CABG for uniform comorbidity ascertainment. Patients with a functioning renal transplant at the time of CABG were excluded.

Follow-up and Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was death from any cause as determined from the USRDS patient file, for which information on patient deaths is ascertained irrespective of Medicare coverage status. Follow-up for the primary outcome was until death or January 1, 2010, whichever came first.

The secondary outcome was a composite of first myocardial infarction (MI) or death from any cause. We defined MI as a diagnosis code of 410.xx as a primary hospitalization diagnosis code or 410.x1 in any secondary diagnosis code position. An MI occurring during the index hospitalization was not considered an outcome, since it may have occurred prior to the revascularization. Because ascertainment of MI required hospitalization information, we followed patients for the composite outcome until death, the time that Medicare Part A and B coverage ended, or January 1, 2010 whichever came first.

Covariates

We obtained data on age, sex, race (white, black, and other), dialysis modality (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis), duration of ESRD, cause of ESRD, and history of any failed kidney transplant from the USRDS patient and treatment history files.

We defined comorbid conditions using disease- or condition-specific diagnosis and procedure codes from at least 1 inpatient or at least 2 outpatient encounters separated by at least one day in the six months prior to (but not including) the date of CABG 10. We identified the following cardiovascular comorbid conditions: atrial fibrillation, prior MI, arrhythmias, heart failure, hypertension, pacemaker, stroke, transient ischemic attack, unstable angina, valvular disease, ventricular fibrillation, implantable cardiac defibrillator, and peripheral vascular disease. Other medical comorbid conditions included diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, systemic cancer, dementia, depression, tobacco use, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, obesity, central nervous system bleed and other vascular lesions, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer disease, psychosis, human immunodeficiency virus, pulmonary hypertension, rheumatological disease, hyperparathyroidism, and electrolyte or metabolic derangements such as hyper- and hyponatremia, hyper- and hypokalemia, hyper-and hypocalcemia, phosphorus disorders, magnesium disorders, acidosis, alkalosis, and mixed acid/base disorders. We also identified patients presenting with an acute MI during the index hospitalization.

To adjust for differences in prior health care utilization, we identified the number of non-nephrology outpatient visits, number of hospitalized days, and patients who had any nursing home stay in the six months prior to the index date. We also categorized patients into one of nine U.S. Census geographical regions based on the zip code in which they received ESRD treatment.

Statistical Analysis

All baseline characteristics were presented using means (standard deviations) and counts (percentages) for both exposure groups and compared using t-tests for continuous and χ2-tests for categorical analyses as appropriate. We modeled the IMA treatment association with outcome using univariate Cox regression and then adjusted for additional factors in two nested multivariable models. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, calendar year, the U.S. Census region, and covariates related to the patient’s ESRD treatment such as dialysis type, cause of disease, the years of dialysis treatment, and any history of kidney transplantation. Model 2 additionally adjusted for the comorbid conditions and health care utilization factors listed above.

In a companion analysis, we employed propensity-score matching to minimize potential treatment selection biases in measured cofounders 18,19. We used multivariate logistic regression to estimate a patient’s probability of receiving IMA (the propensity score), including all of the variables listed above used in the multivariable-adjusted models. Each patient who received an SVG was then matched on propensity score to one IMA patient with the closest propensity score to within 1%. We used a greedy matching algorithm to select iteratively matched pairs among those not yet selected. We further required that all matched pairs be selected from the same calendar year to control for any secular trends. The cohort restricted to propensity-score matched pairs was then evaluated for similarity in outcome hazards using univariate Cox regression with coronary graft type being the sole variable. We also fit multivariable Cox regression models to the matched cohort using all available covariates.

We hypothesized that the association of IMA versus SVG use and outcomes would vary by certain factors. Therefore, we tested for effect modification by sex, age (dichotomized at 65 years), race (white versus non-white), diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease and heart failure by creating a multiplicative interaction term in the fully adjusted model (Model 2) in the matched cohort. To account for multiple hypotheses testing, we used a Bonferroni corrected p-value for interaction threshold of 0.008 (0.05/6). All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 4.3 (Cary, NC) and R 2.12.2.

RESULTS

We identified 14,316 patients on maintenance dialysis undergoing their first recorded multivessel CABG, 10,556 (74%) of whom received revascularization using an IMA; the remaining 3,760 (26%) received only SVG. The proportion of patients with IMA use increased from 62% in 1997 to 85% in 2009 (Figure 1). Patients receiving an IMA tended to be younger, were more often male, of white race, and had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus compared with patients receiving SVG, whereas most other comorbid conditions were more common in the SVG group (Table 1). The propensity score model had a C-statistic of 0.66, indicating modest predictive ability. We were able to match 3,654 (97%) of patients receiving SVG to an equal number of patients receiving IMA. As expected, the baseline variables were generally well balanced between the two groups in the propensity-score matched cohort (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of coronary artery bypass surgeries using the internal mammary artery by index year. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Abbreviations: IMA=internal mammary artery; SVG=saphenous vein graft

Table 1.

Selected baseline characteristics of the full and matched cohorts.

| Full Cohort | Propensity-Score Matched Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| IMA N=10,556 |

SVG N=3,760 |

p | IMA N=3,654 |

SVG N=3,654 |

p | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 62.4 (10.8) | 64.9 (10.6) | <0.0001 | 64.7 (10.2) | 64.7 (10.6) | 0.96 |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 65.2 | 56.6 | <0.0001 | 57.4 | 57.4 | >0.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | <0.0001 | 0.42 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| White race | 66.9 | 64.0 | 64.2 | 64.2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Black race | 25.7 | 29.1 | 29.4 | 28.9 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Other/Unknown | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 6.9 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hemodialysis | 90.5 | 92.0 | <0.005 | 91.3 | 91.9 | 0.36 |

|

| ||||||

| Prior failed kidney transplant | 5.1 | 4.1 | 0.02 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 0.52 |

|

|

||||||

| Years on dialysis, median (IQR), years |

2.7 (1.4- 4.7) |

2.8 (1.5- 4.8) |

0.06 | 2.7 (1.4-4.7) | 2.8 (1.5-4.9) | 0.03 |

|

|

||||||

| Cause of end-stage renal disease |

<0.0001 | 0.93 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes | 57.1 | 53.2 | 53.8 | 53.4 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Hypertension | 23.5 | 27.2 | 26.7 | 26.7 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Glomerulonephritis | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.4 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Other/Unknown | 11.0 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 11.5 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Non-nephrology outpatient visits, median (IQR) |

13 (8-20) | 13 (7-20) | 0.08 | 12 (7-20) | 13 (7-20) | 0.2 |

|

|

||||||

| Hospital days prior to index date, median (IQR) |

4 (2-10) | 5 (2-11) | <0.0001 | 5 (2-11) | 5 (2-11) | 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Utilized skilled nursing facility |

4.8 | 5.0 | 0.61 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 0.87 |

|

| ||||||

| Acute MI on index presentation |

22.7 | 27.3 | <0.0001 | 26.4 | 26.7 | 0.79 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 8.8 | 10.5 | <0.0001 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 0.54 |

|

| ||||||

| Prior MI | 19.5 | 21.2 | 0.02 | 21.3 | 21.3 | >0.99 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart failure | 38.5 | 43.3 | <0.0001 | 43.3 | 42.7 | 0.65 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 80.0 | 78.4 | 0.05 | 78.2 | 78.4 | 0.84 |

|

| ||||||

| Unstable angina | 28.6 | 30.3 | 0.05 | 30.5 | 30.2 | 0.78 |

|

| ||||||

| Valvular disease | 15.4 | 17.7 | <0.0001 | 17.9 | 17.6 | 0.74 |

|

| ||||||

| Peripheral vascular disease |

24.0 | 24.1 | 0.89 | 25.0 | 24.1 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 64.9 | 59.8 | <0.0001 | 60.5 | 60.3 | 0.87 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 26.4 | 22.0 | <0.0001 | 21.9 | 22.2 | 0.71 |

Abbreviations: IMA – internal mammary artery; IQR – interquartile range; MI – myocardial infarction; SD – standard deviation; SVG – saphenous vein graft.

All-cause Mortality

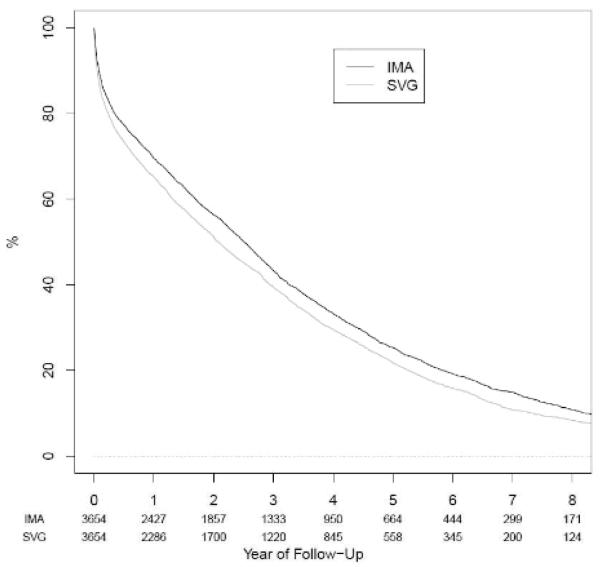

In the full cohort, the median follow-up time was 1.9 years (interquartile range 0.5 to 3.9 years) and 1.9 years (interquartile range 0.4 to 4.0 years) in the matched cohort. During 37,043 person-years of follow-up, 10,154 patients died, leading to an average mortality rate of 27.4 per 100 person-years. The five-year survival rates in the matched cohort were 25.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 23.8% to 26.9%) for IMA and 21.7% (CI 20.3% to 23.3%) for SVG patients (Figure 2). In unadjusted analyses using the full cohort, the hazard ratio (HR) for death was 0.76 (CI 0.73 to 0.80) for IMA versus SVG. This HR was attenuated after adjustment for all other baseline covariates and was not materially changed in analyses using the propensity score-matched cohort (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for coronary artery bypass grafting using internal mammary artery (IMA) versus saphenous vein graft (SVG) in the matched cohort (log-rank p-value <0.0001); numbers below each year represent the number of patients remaining in the cohort at each time point.

Table 2.

Relative hazards of specified outcomes for patients receiving coronary artery bypass grafting using internal mammary artery versus saphenous vein graft in the matched cohort.

| Full Cohort HR (95% CI) |

Matched Cohort HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Death | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.76 (0.73-0.80) | 0.88 (0.84-0.93) |

| Model 1 | 0.85 (0.81-0.88) | 0.89 (0.84-0.93) |

| Model 2 | 0.88 (0.84-0.92) | 0.88 (0.84-0.93) |

| Outcome: Death or myocardial infarction | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.91 (0.87-0.94) | 0.91 (0.87-0.935) |

| Model 1 | 0.86 (0.83-0.90) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) |

| Model 2 | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) | 0.91 (0.87-0.96) |

Abbreviations: HR – hazard ratio; CI – confidence interval;

Note: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, calendar year, the U.S. Census region, and covariates related to the patient's ESRD treatment such as dialysis type, cause of disease, the years of dialysis treatment, and any history of kidney transplantation; Model 2 additionally adjusted all identified comorbid conditions and health care utilization factors.

We found no evidence of significant modification of the IMA treatment effect by sex, age, race, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, or heart failure (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for coronary artery bypass grafting using internal mammary artery (IMA) versus saphenous vein graft (SVG) in the specified subgroups.

Composite outcome: non-fatal myocardial infarction or death

We also conducted corresponding analyses for the secondary composite endpoint of time to death or MI. Over 31,698 person years of follow-up, 12,775 events were recorded of which 3,736 (29%) were non-fatal MI and 9039 (71%) were deaths. In the full cohort, IMA was associated with a lower risk for non-fatal MI or death compared with SVG (Table 2) in unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The results were not materially changed in analyses using the propensity-matched cohort (Table 2, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for survival free of myocardial infarction for coronary artery bypass grafting using internal mammary artery (IMA) versus saphenous vein graft (SVG) in the matched cohort. Numbers below each year represent the number of patients remaining in the cohort at each time point.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that use of the IMA is associated with a 12-15% lower risk of death and a 9-14% lower risk of the composite outcome of death or MI compared with use of SVG in patients with ESRD undergoing initial multivessel CABG across several models. However, the overall five-year survival rate was only 25.3%, regardless of conduit type. Our results did not vary by sex, age, race, or the presence of diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and heart failure.

Our study extends the findings or previous studies of CABG using IMA versus SVG in a general coronary disease population to patients with ESRD on dialysis. Our results are consistent with the only randomized trial of IMA versus SVG to date 3, which showed a lower occurrence of the composite outcome of death, MI, repeat revascularization, or cardiac hospitalization in a general coronary artery disease population (31% versus 51%, respectively, p < 0.05). Our results are also consistent with a recent analysis using pooled individual patient-level data from eight clinical trials of CABG compared to percutaneous coronary revascularization 17, which showed a lower risk of death (HR 0.77, CI 0.62 – 0.97) and death or MI (HR 0.83, CI 0.69-1.00) in the subgroup of patients receiving CABG with IMA compared to SVG.

The association among use of the IMA and improved outcomes is qualitatively similar but quantitatively more modest in our ESRD cohort than in the general coronary disease population. This may be due in part to the short lifespans of these patients, who had a five-year survival rate of 23.5% irrespective of graft type in our study. By comparison, the five-year survival rate among patients undergoing CABG in randomized trials was close to 90% 20. In addition, several small studies and case reports have suggested that myocardial ischemia and symptomatic angina can occur during hemodialysis in patients who have had a CABG with an IMA and dialyze using an upper extremity arteriovenous fistula due to hemodynamic steal from the ipsilateral (and in some cases, the contralateral) IMA 12-15. We did not have information regarding the side of the dialysis access in relation to the IMA however. Therefore, whether this issue contributed to the lower associated benefit of IMA versus SVG in our patient population compared with a non-dialysis population deserves further study.

We pursued the parallel methods of direct multivariable adjustment and propensity matching to mitigate the potential for treatment selection bias due to confounding in the measured covariates. These methods independently produced very similar results across models and outcomes. In spite of these efforts, this study has a variety of limitations. The selection of IMA or SVG treatment was not randomized, so the results may be biased by unmeasured patient factors. Important clinical factors such as left ventricular systolic function or clinical urgency that may have influenced the selection of treatments and outcomes were not available in our dataset. In addition, we did not have detailed information on coronary anatomy, and therefore could not assess whether the results differed by specific bypass targets such as the left main or left anterior descending artery. We lacked records on use of statins, beta-blockers, or other potentially cardioprotective medications. However, we have no reason to suspect that patients revascularized with IMA versus SVG would systematically receive different cardiovascular medications post-procedure. Finally, the administrative Medicare claims data captured in the USRDS code for the presence of comorbid conditions, but not for their severity, so complete adjustment for comorbid conditions was not feasible.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our results suggest that the use of IMA grafts during CABG is associated with lower mortality and cardiovascular morbidity compared to the use of SVG in patients with ESRD on dialysis. These results suggest that the growing use of IMA grafts in this population is appropriate and beneficial. The high mortality rate in this patient population underscores the need to find more effective treatments in patients with concomitant ESRD and coronary artery disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted under a data use agreement between Dr. Winkelmayer and the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). An NIDDK officer reviewed this manuscript for research compliance and approved of its submission for publication. Data reported herein were supplied by the USRDS. Interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Funding: Dr. Chang is supported by the American Heart Association (AHA) National Scientist Development Grant (12SDG11670032). Dr. Shilane is supported by a grant from the AHA (0875162N). The AHA had no role in design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of the data or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Dr. Winkelmayer is supported by grant 1R21DK089368 (entitled, “Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for the Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease in Individuals with Chronic Kidney Disease”), as well as grants 1R21DK077336, 1R01DK090181, 1R01AR057327, 1R01DK090008, 1R01DK095024 (all from the National Institutes of Health), as well as by contracts HHSAA2900200500401 and HHSN268201100003C.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Charytan D, Kuntz RE, Mauri L, DeFilippi C. Distribution of coronary artery disease and relation to mortality in asymptomatic hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2007;49(3):409–416. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, et al. Long-term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: Results from a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeff RH, Kongtahworn C, Iannone LA, Gordon DF, Brown TM, Phillips SJ, et al. Internal mammary artery versus saphenous vein graft to the left anterior descending coronary artery: Prospective randomized study with 10-year follow-up. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1988;45(5):533–536. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM, Stewart RW, Goormastic M, Williams GW, et al. Influence of the internal-mammary-artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314(1):1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601023140101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron A, Davis KB, Green G, Schaff HV. Coronary bypass surgery with internal-thoracic-artery grafts — effects on survival over a 15-year period. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(4):216–220. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grondin CM, Campeau L, Lesperance J, Enjalbert M, Bourassa MG. Comparison of late changes in internal mammary artery and saphenous vein grafts in two consecutive series of patients 10 years after operation. Circulation. 1984;70(3 Pt 2):I208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabik JF, 3rd, Lytle BW, Blackstone EH, Houghtaling PL, Cosgrove DM. Comparison of saphenous vein and internal thoracic artery graft patency by coronary system. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(2):544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.07.047. discussion 544-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzog CA, Ma JZ, Collins AJ. Long-term outcome of dialysis patients in the united states with coronary revascularization procedures. Kidney Int. 1999;56(1):324–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzog CA, Strief JW, Collins AJ, Gilbertson DT. Cause-specific mortality of dialysis patients after coronary revascularization: Why don’t dialysis patients have better survival after coronary intervention? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(8):2629–2633. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang TI, Shilane D, Kazi DS, Montez-Rath ME, Hlatky MA, Winkelmayer WC. Multivessel coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention in esrd. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;23(12):2042–2049. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Renal Data System . Usrds 2011 annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the united states, N.I.o.D.a.D.a.K.D. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowley SD, Butterly DW, Peter RH, Schwab SJ. Coronary steal from a left internal mammary artery coronary bypass graft by a left upper extremity arteriovenous hemodialysis fistula. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2002;40(4):852–855. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.35701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, Ikawa S, Hayashi A, Yokoyama K. Internal mammary artery steal in a dialysis patient. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2003;75(1):270–271. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahbar R, McGee WR, Birdas TJ, Muluk S, Magovern J, Maher T. Upper extremity arteriovenous fistulas induce modest hemodynamic effect on the in situ internal thoracic artery. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2006;81(1):145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudino M, Serricchio M, Luciani N, Giungi S, Salica A, Pola R, et al. Risks of using internal thoracic artery grafts in patients in chronic hemodialysis via upper extremity arteriovenous fistula. Circulation. 2003;107(21):2653–2655. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074777.87467.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blacher J, Demuth K, Guerin AP, Safar ME, Moatti N, London GM. Influence of biochemical alterations on arterial stiffness in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(4):535–41. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hlatky MA, Shilane D, Boothroyd DB, Boersma E, Brooks MM, Carrié D, et al. The effect of internal thoracic artery grafts on long-term clinical outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2011;142(4):829–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Agostino RB., Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hlatky MA, Boothroyd DB, Bravata DM, Boersma E, Booth J, Brooks MM, et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary interventions for multivessel disease: A collaborative analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9670):1190–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]