Abstract

Overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family has been implicated in ovarian cancer because of its participation in signaling pathway regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation, motility, and survival. Currently, effective diagnostic and therapeutic schemes are lacking for treating ovarian cancer and consequently ovarian cancer has a high mortality rate. While HER2 receptor expression does not usually affect the survival rates of ovarian cancer to the same extent as in breast cancer, it can be employed as a docking site for directed nanotherapies in cases with de novo or acquired chemotherapy resistance. In this study, we have exploited a novel gold nanoshell-based complex (nanocomplex) for targeting, dual modal imaging, and photothermal therapy of HER2 overexpressing and drug resistant ovarian cancer OVCAR3 cells in vitro. The nanocomplexes are engineered to simultaneously provide contrast as fluorescence optical imaging probe and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) agent. Both immunofluorescence staining and MRI successfully demonstrate that nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates specifically bind to OVCAR3 cells as opposed to the control, MDA-MB-231 cells, which have low HER2 expression. In addition, nanocomplexes targeted to OVCAR3 cells, when irradiated with near infrared (NIR) laser result in selective destruction of cancer cells through photothermal ablation. We also demonstrate that NIR light therapy and the nanocomplexes by themselves are non-cytotoxic in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a successful integration of dual modal bioimaging with photothermal cancer therapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. Based on their efficacy in vitro, these nanocomplexes are highly promising for image guided photo-thermal therapy of ovarian cancer as well as other HER2 overexpressing cancers.

Keywords: Gold nanoshells, Multimodal NIR imaging, Photothermal therapy, Theranostic, Ovarian cancer

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy, and is the fourth most frequent cause of cancer-related death of women in Western countries. In 2008, there were 21,650 new cases of ovarian cancer and 15,520 deaths reported in the United States (1). However, the difficulty in detecting ovarian cancer at an early stage, aggressiveness, and the lack of effective therapy contribute to high mortality (2). Currently recognized prognostic factors in advanced ovarian cancer (AOC) are primarily clinical, including patient performance status and characteristics of tumor volume, stage classified by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), residual tumor size after initial surgery, and presence of ascites. However, most prognostic models proposed in the literature do not include biological factors (3). In 2004, a study of HER2 overexpression in ovarian cancer by Camilleri-Broët and coworkers using immunohistochemically on paraffin-embedded tissues and their prognostic impact analyzed of HER2 protein level found an independent prediction with both overall and disease-free survival on multivariate analysis (4). HER2 is frequently overexpressed in ovarian cancer patients; the overexpression rate has been reported in a wide range from 8% to 66% (4–8). The 66% figure was reported by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) study in 74 cases (8); 53% in 181 cases (7), 22% in 23 cases (6), and 16% in 95 cases (4). Dimova (5) analyzed multiple samples applying the highly reliable method of FISH on tissue microarray, containing 1006 ovarian tumors and reported 8% HER2 amplifications in ovarian malignant epithelial tumors. HER2 overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis due to acquired chemotherapy resistance. The HER2 positive cell line OVCAR3 was chosen because it was isolated from a malignant effusion and is resistant to clinically relevant doses of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, melphalan, and cisplatin (9, 10), and is a good candidate for demonstrating molecularly targeted and images guided photo-therapy.

The design and development of novel nanoagents that synergistically incorporate multiple functionalities, including targeting, imaging and therapy, all within the same nanoprobe is emerging rapidly as an impending alternative to traditional therapeutic drugs and imaging agents (11). This promising new paradigm is hence termed as “Theranostic” which entails the efficient integration of therapeutic and diagnostic moieties into a single nanoagent. Nanoparticles in the size range of 5–250 nm are effective interventional agents for cancer because of their unique size, which allows passive accumulation in tumors, and because of their ability to carry multiple diagnostic and therapeutic payloads. The majority of clinical trials involving nanoparticles focus on targeted chemotherapy delivery (12), as despite the emerging molecular medicine based shift towards cancer-specific cytostatic agents, cytotoxic chemotherapy is still considered more effective against broad patient populations. While nanocarrier-based chemotherapy can minimize traditional side effects, it is not externally controlled and in the case of liposomes, which have been approved since the 1990s, the inability to guarantee intracellular drug delivery often results in treatment failure.

Alternative cancer therapeutics based on the photothermal response of gold nanostructures designed to absorb NIR, tissue-penetrating light has exhibited near 100% efficacy in the remission of tumors, and stands as one of the most promising new technologies to emerge from nanoscience research in the past decade. Following the initially demonstrated therapeutic success of gold nanoshells, other gold nanoparticles such as gold nanorods, hollow gold nanospheres, and gold nanocages have also been used to demonstrate similar, highly promising therapeutic responses (13–17). Gold-based nanostructures show particular promise as theranostic agents, based on their straightforward adaptability to integrate targeting, diagnostic, and therapeutic functionalities into a single, hybrid, multifunctional nanoscale complex (18, 19). Silica core gold nanoshells with plasmon resonance in NIR region effectively absorb NIR light and generate hyperthermia for externally controlled tumor cell death (14, 18, 20). Similarly SPIO particles can be exposed to alternating magnetic fields (AMF) for tumor hyperthermia (21). At present nanoshells can not be directly imaged in deep tissue, as only indirect absorbing/scatter based contrast has been exploited. While highly sensitive, noninvasive NIR imaging is constrained by limited photon penetration in tissue and cases like cancer metastasis in deep axillary lymph nodes, and organs like ovary, lungs, liver, skeleton and brain will be outside its purview for foreseeable future. MR imaging does not have tissue depth constraints but SPIO particles require heavy tumor loading for imaging and therapy (21), and if in case surgery is needed, they do not provide any intraoperative guidance for tumor margin determination. The complimentary capabilities of NIR and MRI imaging provide the motivation for combining NIR light and magnetic field based imaging and therapy in one nanoparticle. Gold nanostructures with integrated NIR emitters for fluorescence enhancement of optical tomography, and with iron oxide nanoparticles for MRI enhancement, can serve as simultaneous theranostic reporter-actuators. With antibody or peptide conjugation, this theranostic hybrid nanoparticle (hNP) can be delivered to specific cells or tissues for therapy, with reporter functionalities providing tracking capabilities before, during and after treatment Recently, some theranostic nanoprobes have been synthesized with complex geometries (22–26), however, their capability have been mostly limited to a single imaging modality such as either MRI or optical imaging (OI). Recently, we designed and utilized a multifunctional gold nanoshell-based theranostic complex (nanocomplex) to actively target, image via MRI and fluorescence optical imaging, and induce photothermal tumor ablation in breast cancer cells with NIR illumination***. In this study, we demonstrate the efficacy of these nanocomplexes for simultaneous diagnosis and therapy of ovarian cancer cells in vitro andfurther demonstrate the non-toxicity of NIR therapy and the nanocomplexes.

The nanocomplex consist of a gold (Au) nanoshell encapsulated in a silica (SiO2) shell, which is doped with superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) and a NIR emitting fluorophore, Indocyanine green (ICG). Au nanoshells are optically tunable nanoparticles that consist of a SiO2 core surrounded by a thin Au shell (27). Based on the relative dimensions of the shell thickness and core radius, nanoshells can be designed to scatter and/or absorb light over a broad spectral range, including the NIR. The NIR wavelength region provides maximal penetration of light through soft tissue, including hypoxic regions in tumors, and irradiation of tumors with NIR laser light can lead to thermal ablation (28). The nanoshells enhance the fluorescence of ICG molecules incorporated into the outer layer of the nanocomplex. ICG is an Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved fluorescent emitter with a quantum yield of ~ 1.3% in aqueous media. When incorporated into the oxide layer just outside the gold shell layer, the nanoshell enhances the fluorescence quantum yield by nominally 4500%, resulting in a very bright NIR fluorescent probe (29). The nanoscale SPIO layer concurrently provides a high MR contrast thus enabling multimodal imaging with the same agent. Accumulation of nanoshells in tumor cells can be achieved via passive extravasation based on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) of small particles associated with the leaky tumor vasculature (30). However, when targeted using antibodies against oncoproteins overexpressed on cell surfaces, a higher concentration of nanoshells can be selectively bound to cell surfaces and enable extended periods of diagnostic imaging as well as therapy.

The photothermal properties of nanoshells are attributed to their ability to absorb NIR light at their plasmon resonant wavelength, due to their large absorption cross section, efficiently converting the light energy to heat. The heat generated by the nanoshells raises the local temperature in their direct vicinity, resulting in the thermal ablation of cancer cells (13, 31). In particular, targeted nanoshells will accumulate at the specific tumor site, enabling photothermal therapy of cancer cells only, and greatly minimizing damage to adjacent healthy cells. In this study, we have demonstrated that NIR laser irradiation at low power densities, as well as nanoshells by themselves, are non-toxic and do not induce cytotoxicity. These molecularly targeted nanocomplexes are highly promising and clinically relevant for providing molecule-specific diagnostic information that will enable the detection and treatment of cancer long before phenotypic changes occur. In practice, this will provide an efficient tool for the detection of tumors at an early stage and provide a benign therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

I. Nanocomplex Fabrication

Au nanoshells (NS) [r1, r2] = [60, 74] nm were fabricated by seed mediated electroless plating of Au onto SiO2 colloidal nanospheres, as previously reported (27). Briefly, SiO2 nanospheres of 60±2 nm radii were synthesized via the Stöber method (32) and then functionalized with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma). The aminated silica nanospheres were decorated with small Au colloid (2–3 nm), fabricated by the method reported by Duff et. al. (33). A continuous Au shell was grown around the SiO2 nanospheres by reducing Au from a 1% solution of HAuCl4 in the presence of gaseous CO. Water soluble SPIO (Fe3O4) nanoparticles of 10±3 nm diameter were fabricated by following a procedure previously reported (34) and functionalized with APTES. The Au nanoshells were then coated with the amine terminated Fe3O4 overnight and centrifuged to remove excess Fe3O4. The NS coated with the Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NS@ Fe3O4) were then encapsulated with silica with the fluorophore ICG doped within the silica layer. Briefly, NS@ Fe3O4 were mixed with fresh ethanol and 28% NH4OH (Fisher) and a 1 mL ethanolic solution of ICG. Immediately fresh TEOS was added to the solution mixture and the vessel was sealed and vigorously stirred for 45 min. The nanocomplexes were stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C overnight protected from light. After 24 h, the particles were centrifuged and redispersed in ethanol. The absorbance of the supernatant was monitored to account for unbound ICG in the supernatant. The concentration of the supernatant was then subtracted from the initial concentration of ICG which was added to calculate the amount of ICG doped within the silica layer. The final nanocomplexes concentration after resuspension in ethanol was at ~109 particles/mL and the ICG concentration was ~ 500 ±50 nM.

II. Anti-HER2 Conjugation to Nanocomplexes

Anti-HER2 (c-erbB-2) / HER-2 / neu epitope specific rabbit antibody 200 μg/mL (Thermo Scientific) was biotinylated with a 1 mM solution of Sulfo-NHS-Biotin (Pierce) at 4 °C for 3 h. After conjugation, the anti-HER2-biotin reagent was dialysed in PBS (phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2) to remove excess biotin. The nanocomplexes were attached to streptavidin by initially functionalizing with (3-mercaptopropyl) triethoxysilane (MPTES, Sigma) to generate thiol terminated nanoparticles. These thiol terminated nanoparticles were redispersed in phosphate buffer and mixed with streptavidin maleimide (Sigma) solution and mildly stirred for 4 h at 4 °C. The streptavidin conjugated nanocomplexes were centrifuged and resuspended in 5 mL phosphate buffer and incubated with biotinylated anti-HER2 at 4 °C overnight. The nanocomplexes were centrifuged at 280 g for 5 min to remove unbound antibody and finally redispered in salt free phosphate buffer at pH 7.2. The number of antibodies per nanocomplex was quantified by utilizing ELISA. The anti-HER2 conjugated nanocomplexes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled Anti-Rabbit IgG (HRP-AR, Sigma A0545) for 1 h after non-specific reaction sites were blocked with 3% solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma). The HRP bound nanocomplexes were developed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Sigma) and compared with a HRP Anti-Rabbit IgG standard curve ranging from 0.02– 0.0003125 μg/ml. Results were analyzed using a spectrophotometer (data not shown).

Extinction spectra were obtained using a Cary 5000 UV/Vis/NIR spectrophotometer. The ICP-OES analysis were done using a Perkin Elmer inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer the spectral range of 165–800 nm.

III. In vitro Fluorescence Optical Imaging

OVCAR3 Ovarian Adenocarcinoma Human (Homo sapiens) cells, and the control cell line, MDA-MB-231 Breast Adenocarcinoma Human (Homo sapiens) cells were grown in 1× MEM/F-12 50/50 (Dulbecco’s Mod. of Eagle’s Medium/Ham’s F-12 50/50 mix with L-glutamine), 1% antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment and were detached from culture with trypsin (0.05%) and EDTA (0.02%) and resuspended in media for passaging to wells. 3×105 cells of OVCAR3 and MDA-MB-231 were plated in each well of 4 well plates, respectively, and allowed to incubate. Subsequently, cells were washed with 1×PBS twice and fixed with PFA (3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS). Cells were then quenched with Lysine-periodate and permeabilized with 0.2% triton, following which they were washed twice with PBS. 10% Normal Goat Serum (NGS) solution was added to each well plate and incubated for 15 min, following which excess NGS was removed and the cells were incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and unconjugated nanocomplexes at particle concentration 2×109 particles/mL for 2 h at 4 °C. After 2 h, the cells were washed with PBS to remove unbound nanocomplexes, following which the secondary antibody, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The cells were again washed with PBS while protected from light for excess secondary antibody removal. The cell plates were then mounted on slides with mounting media containing DAPI (Invitrogen) and prepared for fluorescence imaging.

Fluorescence emission spectra were obtained using Jobin Yvon Fluorolog 3 and the samples were excited at 780 nm. To acquire the fluorescence images we used a Leica fluorescence microscope (DM6000 B; Leica Microsystems GmbH) with a 100 W xenon lamp and specific filters. The images were obtained using cutoff filters with appropriate excitation and emission wavelengths as listed in Table-1.

Table-1.

Optical filter parameters employed for fluorescence microscopy

| Dye | Excitation (nm) | Emission (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 360 | 470 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 | 480 | 530 |

| ICG | 720 | 820 |

| Calcein | 480 | 530 |

| PI | 520 | 620 |

IV. In vitro MRI

1×106 cells of OVCAR3 and MDA-MB-231 were plated in each well of 60×15 mm Style cell culture dishes respectively, and allowed to incubate. A similar procedure was followed as described in section III. After 2 h incubation with the nanocomplexes, the cells were washed with PBS, followed by scraping the cells from the bottom of the petri dish, dispersed in 500 μL PBS, and centrifuged at 1100 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed leaving ~100 μL cells containing nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, and unconjugated nanocomplexes in the Eppendorf tubes, respectively. 500 μL of 0.5% agarose gel was added to each tube and the samples were left at 4 °C for 10 min to allow the agarose to solidify. The tubes containing the solidified agarose gel with OVCAR3 and MDA-MB-231 cells, with the nanocomplexes suspended within the gel were directly utilized for MR Imaging.

MRI experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance Biospec, 9.4 T spectrometer, 21 cm bore horizontal imaging system (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA) with a 35 mm volume resonator. In vitro imaging of cells suspended in agarose was done using a 3D RARE (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement) sequence with a TR/TE equal to 2000/20 ms with a RARE factor of 8 leading to an effective TE of 60 ms. FOV was 25.6×25.6×12.8 mm with an acquisition matrix of 128×128×64 yielding an isotropic 200 μm resolution.

Maximum intensity projections were created from the 3D MRI data using a threshold segmentation approach in MATLAB® (2008a, The Mathworks, Natick, MA). The threshold was set at the average minus twice the standard deviation of the sample. Pixels under this value were considered to be hypointense and are labeled as black in the image. The surrounding normotense agarose is labeled as a transparent light blue. Each hypointense pixel contains a cluster of labeled cells as the scan resolution is not enough to identify individual cells.

V. In vitro Photothermal Therapy and Cytotoxicity

OVCAR3 and MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in 6 wells plate and incubated with either nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates or unconjugated nanocomplexes, which were already suspended in media appropriate for the cell line at a concentration of 2×109 particles/mL. Cells were incubated with nanocomplexes for 2 h and then washed with PBS three times, after changing culture medium directly used for photothermal therapy. Cells were not fixed with 3.7% PFA or quenched with Lysine-periodate in these experiments to ensure maximum cell viability. Laser ablation was performed using an NIR laser at 808 nm (L808P200, Thorlabs Inc.) for 10 min at a power density of 5.81 W/cm2 and a spot size of ~ 0.8 mm diameter. After irradiation, cells were rinsed gently with PBS and incubated with media for 4 h. Cell viability was assessed using Calcein to stain live cells and propidium iodide (PI) to stain dead cells. A dye solution mixture containing 3 μM PI and 2 μM Calcein was prepared and 150 μL was added to each well with nanocomplexes which were photothermally ablated. For cytotoxicity studies, cells were incubated with nanocomplexes-anti-HER2 conjugates, unconjugated nanocomplexes, and no nanocomplexes. These cells were not illuminated with the NIR laser. After incubating the cells with Calcein/PI mixture for 30 min at 37 °C, a cover slip was mounted and imaged. In this stain, calcein AM enters the cells and is cleaved by esterases in the live cells to yield cytoplasmic green fluorescence. Dead cells are determined by plasma membrane integrity. This can be assessed in two ways: The ability of a cell to prevent a fluorescent dye from entering it and the ability of a cell to retain a fluorescent dye within it. When a cell dies, its plasma membrane becomes permeable enabling fluorescent dyes enter the cell. This allows PI to enter and bind to nucleic acids generating a red fluorescence. PI is membrane impermeant and generally excluded from viable cells.

Results

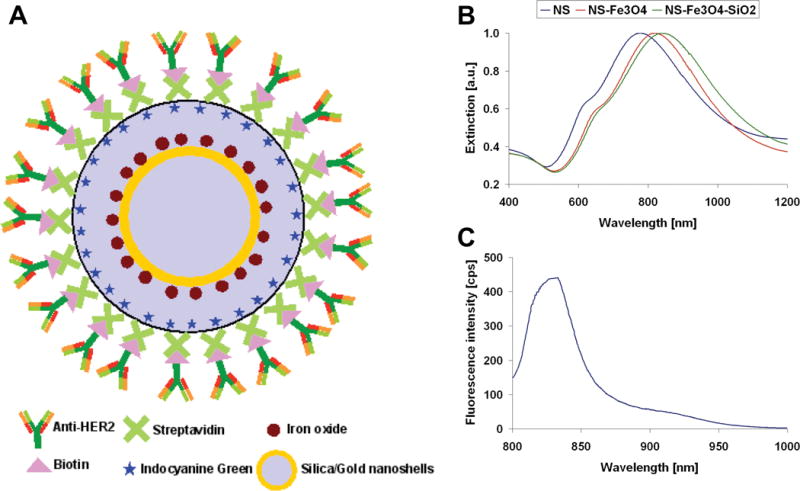

A schematic illustration of the nanocomplexes conjugated with antibody is depicted in Figure 1A. NS were surrounded with thin (nominally 5–10 nm) epilayers of SiO2 doped with the fluorophore, ICG, and SPIO nanoparticles. This was followed by streptavidin binding and biotinylated anti-HER2 conjugation of the nanocomplex. Normalized extinction spectra of the NIR resonant nanoshells, nanoshells after coating with Fe3O4 and after encapsulating in a silica epilayer, are shown in Figure 1B. Fluorescence spectra of ICG doped in the silica layer of the nanocomplexes at 833 nm is shown in Figure 1C. These nanocomplex spectral characteristics provide a better understanding of their functions as imaging probes as well as a therapeutic agent.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of anti-HER2 conjugated nanoshell contrast agents. (B) Extinction spectra of nanoshells (blue) resonant in the NIR at 777 nm, nanoshells after coating with Fe3O4 (red) resonant at 821 nm, and after encapsulating in a silica SiO2 epilayer (green) resonant at 842 nm. (C) Fluorescence spectrum of ICG doped in the silica layer of the nanoshells at 833 nm.

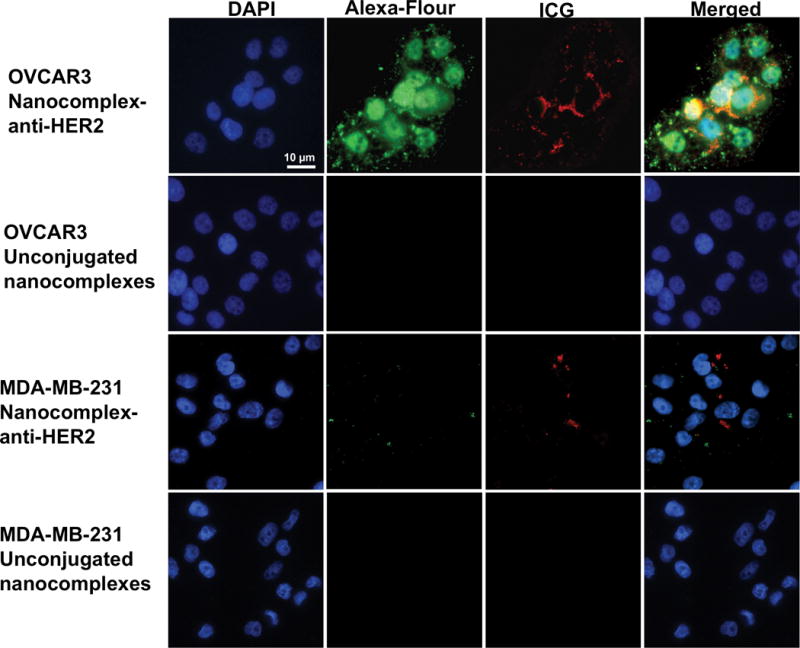

The efficacy of the targeted nanocomplexes-anti-HER2 conjugates to provide image contrast for tumor cells in vitro was established by fluorescence optical imaging. Fluorescence images of OVCAR3 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and unconjugated nanocomplexes were obtained. MDA-MB-231 Breast Adenocarcinoma Human (Homo sapiens) cells were chosen as a control due to the low levels of HER2 expression present in this cell line (35, 36). Low levels of HER2 expression were used to assign the cell lines into previously clinically defined subtypes, which can be used to guide clinical trial design (37–41). The fluorescence optical images of HER2 positive OVCAR3 cells with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates are shown in Figure 2 where the first column depicts nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), second column illustrates cytoplasm stained with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (green), third column represents NIR fluorescence from ICG doped in silica layer of nanocomplexes (red), and the merged image shown in the last column demonstrate the nanocomplexes binding to the cell membrane. After 2 h incubation with OVCAR3 cells, the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates showed specific binding to the cells. The fluorescence images of OVCAR3 cells incubated with the control, unconjugated nanocomplexes (without antibodies) indicate that the nanocomplexes did not bind to the cells. Due to an absence of the primary antibody (anti-HER2), the secondary antibody did not bind and no signal was observed from the Alexa Fluor 488 as well. Fluorescence images of low HER2 expressing MDA-MB-231 cells with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates show less binding in comparison to OVCAR3 cells. Minimal non-specific binding to the extracellular matrix was observed for the MDA-MB-231 cells, resulting in a very weak NIR signal from the ICG. Similarly, without the primary antibody, the secondary antibody did not bind as well, leading to low fluorescence from Alexa Fluor. The unconjugated nanocomplex incubated with MDA-MB-231 cells also did not bind to the cell membrane. This sequence of experiments demonstrates that the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates significantly target HER2-overexpressing OVCAR3 cells membrane in comparison to MDA-MB-231 cells, which express low levels of HER2.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence optical images of HER2 positive OVCAR3 cells with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates are shown in the top row showing nuclei stained with DAPI (blue) cytoplasm stained with secondary antibody-Alexa-fluor 488 (green), NIR fluorescence from ICG doped in silica layer of nanocomplexes (red), and merged image showing the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates binding outside the cells membrane. Fluorescence images of OVCAR3 cells with the control, unconjugated nanocomplexes are shown the second row. Fluorescence images of low HER2 expressing MDA-MB-231 cells with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and the control are shown in the third and fourth row. Some non-specific binding to the extracellular matrix was observed for MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates. Original magnification is ×400 and the scale bar is 10 μm for all panels.

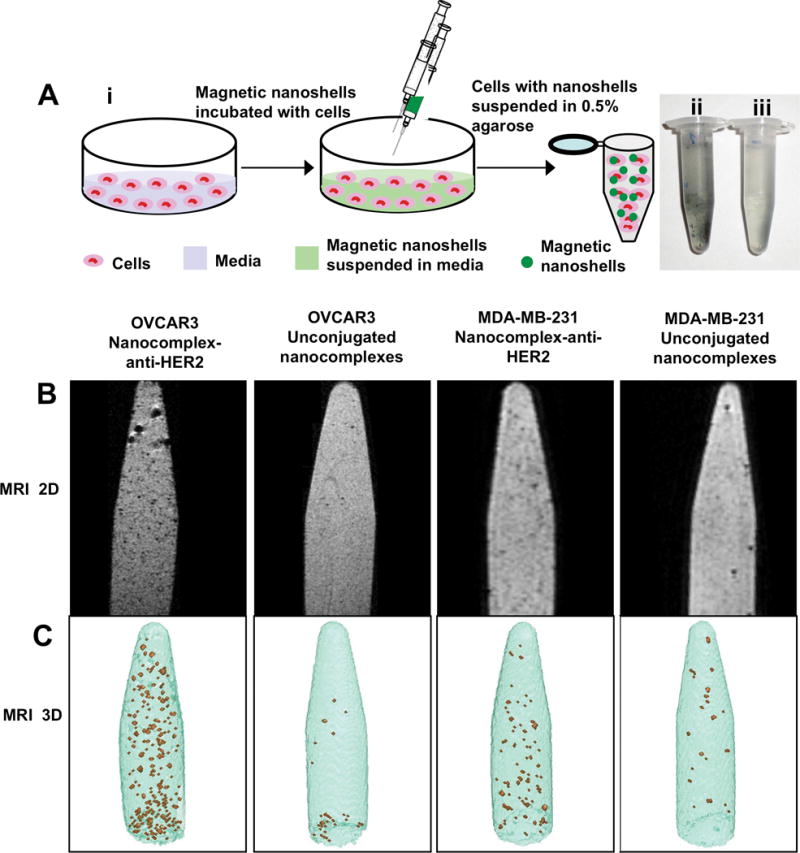

The nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and unconjugated nanocomplexes were incubated with OVCAR3 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells at a concentration of 2×109 particles/mL, containing 0.215 mM Fe nanoparticles (determined by ICP-OES). The schematic representation of sample preparation for in vitro MRI studies is shown in Figure 3Ai. Briefly, cells were incubated with nanocomplexes suspended in media for 2 h and subsequently centrifuged and redispersed in 0.5% agarose. Optical images of OVCAR3 cells bound to nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates suspended in agarose, and OVCAR3 cells with unconjugated nanocomplexes suspended in agarose are shown in Figure 3Aii and 3Aiii. MR 2D images of OVCAR3 cells suspended in agarose with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates are shown in Figure 3B. The cells labeled with nanocomplexes appear as hypointense signals (dark spots) with higher contrast, suggesting that the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates were bound to the OVCAR3 cells. OVCAR3 cells incubated with unconjugated nanocomplexes showed a few hypointense signals, indicating minimal nonspecific binding. MR images of MDA-MB-231 cells suspended in agarose with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates clearly show less binding in comparison to OVCAR3 cells. Additionally, MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the control also demonstrated nominal nonspecific binding.

Figure 3.

(A) (i) Schematic representation of sample preparation for in vitro MRI studies. Magnetic nanocomplexes are incubated with cells, washed after 2 h, centrifuged and suspended in 0.5% agarose. Optical image of (ii) cells with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates suspended in agarose, and (iii) cells with control, unconjugated nanocomplexes suspended in agarose. (B) 2D MR image of HER2 positive OVCAR3 cells and low HER2 expression MDA-MB-231 suspended in 0.5% agarose with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates with ~ 0.215 mM Fe3O4 and control, unconjugated nanocomplexes are shown. (C) Maximum intensity projection of 128×128×64 pixel threshold T2 maps of the images corresponding to the 2D MRI images are shown. The hypointense signals observed both in the 2D and 3D images are the cells labeled with the magnetic nanocomplexes.

The maximum intensity projections (MIP) of 128×128×64 pixel threshold T2 maps, where each pixel represents the cubic volume of 156×156×156 μm, are shown in Figure 3C. The MIP were created from the 3D MRI data using a threshold segmentation approach as described in section VI. The hypointense pixels (brown spots) represent the nanocomplex-labeled cells and the surrounding normointense pixels (blue) represent the agarose medium. These 3D images correspond to the 2D MRI images shown directly above. Each hypointense pixel represented here contains a cluster of labeled cells since the scan resolution is insufficient to identify individual cells. The number of hypointense pixels was quantified to determine the specificity and selectivity of the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates in targeting HER2 expressing cells. Both the MDA-MB-231 and OVCAR3 cells that had been incubated with the unconjugated nanocomplexes showed approximately equal counts of hypointense pixels, due to nonspecific binding. The MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 had 2.3 times the number of hypointense pixels relative to the cell samples incubated with unconjugated nanocomplexes. In comparison, OVCAR3 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates had 9.0 times the number of hypointense pixels relative to OVCAR3 cells incubated with the unconjugated nanocomplexes. OVCAR3 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates also had 3.1 times the number of hypointense pixels as the MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates.

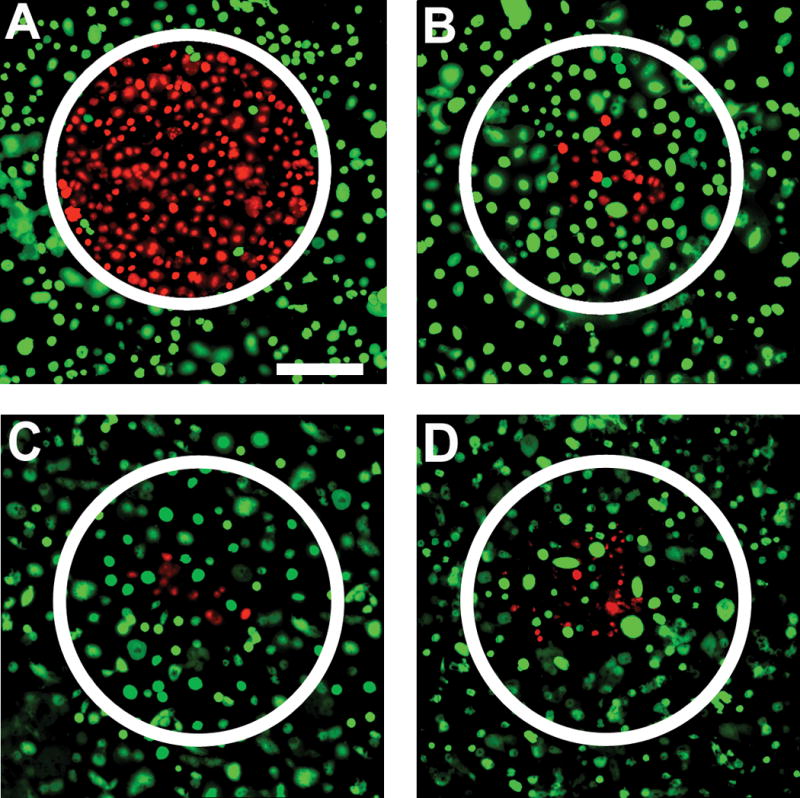

The photothermal ablation of OVCAR3 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates allowing targeted destruction is shown in Figure 4. Both OVCAR3 and MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with the nanocomplexes-anti-HER2 conjugates and unconjugated nanocomplexes were illuminated with NIR laser light at 808 nm for 10 min at a power density of 5.81 W/cm2 and a spot size of ~0.8 mm diameter. Following photothermal therapy, cells were stained with the Calcein/PI mixture. Live cells appeared green due to the calcein stain and dead cells appeared red due to the PI stain. The nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, which were bound to the OVCAR3 cell membrane, produced hyperthermia upon laser irradiation, resulting in cell death (Figure 4A). The increased PI uptake by the dead cells within the laser spot is clearly observable. MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates were also exposed to the same NIR laser treatment, and showed minimal cell death (Figure 4C). A small amount of the unconjugated nanocomplex was nonspecifically bound to both the OVCAR3 cells and the MDA-MB-231 cells, and resulted in some cell death after laser treatment (Figure 4B, 4D). Irradiation of OVCAR3 cells treated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates with NIR laser radiation resulted in selective destruction of these cells. In contrast, MDA-MB-231 cells treated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates with NIR showed no observable effects on cell viability.

Figure 4.

Photothermal ablation and live/dead stain of OVCAR3 cells incubated with (A) nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and (B) control, unconjugated nanocomplexes and treated with NIR laser at 808 nm for 10 min at a power density of 5.81 W/cm2 and spot size of ~0.8 mm diameter. Live cells are stained green with calcein and dead cells are stained red with propidium iodide. Similar staining procedure for MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with (C) nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and (D) control, and treated with NIR laser as well. Original magnification is ×100 and scale bar is 250 μm for all panels.

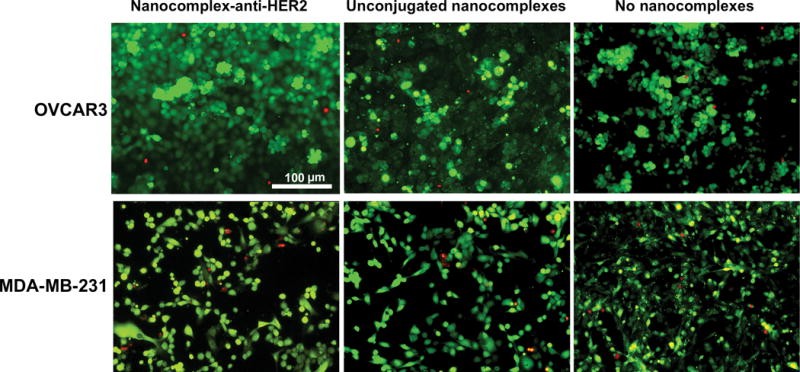

Nanocomplexes by themselves, without photothermal ablation, were observed to be innocuous to cells, and nominal cell cytotoxicity was observed. OVCAR3 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates and the unconjugated nanocomplexes for 2 h, followed by staining with Calcein/PI dye mixture. Cytotoxicity studies of OVCAR3 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, unconjugated nanocomplexes, and control, no nanocomplexes are shown in Figure 5, top row. Similarly, cytotoxicity studies of MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, unconjugated nanocomplexes, and control are shown in Figure 5, bottom row. The results for both cell lines are comparable and minimal differences in cell viability and cell death were observed.

Figure 5.

Absence of cytotoxicity on OVCAR3 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, unconjugated nanocomplexes, and control (no nanocomplexes) are shown in top row. MDA-MB-231 cells incubated with nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates, unconjugated nanocomplexes, and controls are shown in bottom row. Live cells are stained green with calcein and dead cells are stained red with propidium iodide. Original magnification is ×200 and the scale bar is 100 μm for all panels.

Discussion

Currently, the majority of ovarian cancer diagnoses are for rather advanced stages of the disease due to the lack of availability of early detection and treatment strategies. The standard protocols for the treatment of ovarian cancer have included conventional surgical approaches followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy. These standard care treatments often require invasive surgical procedures or other therapies associated with significant side effect profiles, high cost, and poor clinical outcome. Since HER2 receptor amplification occurs in ovarian cancers and is associated with poor clinical outcome, including short survival time and short time to relapse (4–8, 42, 43), it can be targeted with alternative nanoparticle based therapies. Furthermore, HER2 positive cell line OVCAR3 in vitro have also been found to be resistant to clinically relevant drugs including adriamycin, melphalan, and cisplatin, with survival rates of 43%, 45%, and 77%, respectively relative to untreated controls (9). The drug resistance of ovary cancer cells can be effectively addressed by image guided photo/magneto-thermal therapies.

The nanocomplexes utilized here provide a unique platform with targeting, diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities all within the same agent. There are several advantages offered by these nanoscale agents. First, the nanocomplexes effectively assimilate two imaging modalities, MRI and fluorescence imaging, which are non-invasive, safe, clinically relevant, and complementary techniques. While MRI has the advantage of 3D resolution and visualization of overall anatomical background, it lacks sensitivity. Optical imaging methods such as fluorescence provide high target sensitivity, although they lack 3D resolution. Hence combining these two imaging modalities synergistically integrates the advantages of the two techniques and overcomes the disadvantages simultaneously. Second, antibody targeting allows nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates to specifically bind to HER2-overexpressing cell surface receptors. Here, both immunofluorescence staining and MRI successfully demonstrate that nanocomplex-anti-HER2 conjugates bind to HER2-overexpressing OVCAR3 cells in contrast to MDA-MB-231 cells, which have low HER2 expression. Some nonspecific binding was observed for the unconjugated nanocomplexes. This could be attributed to the overall negative charge on the outer surface of the silica layer of the nanocomplex, as a consequence of the fabrication procedure, which interacts electrostatically with the proteins present in the cells. However, the non-specific binding can be reduced with improvised chemical modification of the nanocomplexes in future studies. Third, due to the unique plasmonic properties of the nanocomplexes and tunability in the NIR they can absorb resonant light; effectively convert light to heat, followed by photothermal therapeutic actuation resulting in tumor ablation with near 100% remission rates (13). Fourth, the nanocomplexes have low cytotoxicity and a particle size conducive to passive extravasation from the tumor vasculature (44, 45). This will allow future studies in animal models as these nanocomplexes will accumulate in the tumor enabling simultaneous comprehensive imaging and therapy. In this study, the nanocomplexes have proven beneficial for the treatment of ovary cancer in vitro. Therefore, they can be promising candidates for in vivo studies for ovarian cancer models as well as other tumor types.

In conclusion, this is the first demonstration of a successful integration of dual modal bioimaging with photothermal cancer therapy for the treatment of ovarian cancer cells, using a molecularly targeted gold nanoshell-based theranostic probe. Unlike conventional cancer therapy approaches such as radiation- or chemotherapy, which can have fatal side effects, nanoshell-based photothermal ablation therapy is benign and safe. Moreover, due to their selective accumulation at cancer cells expressing the HER2 cell receptor, only cells retaining the nanoshells will heat up and ablate when illuminated with NIR laser, while neighboring healthy cells will not experience plasmonic heating. These nanocomplexes can potentially be used as a tool for evaluating transmembrane receptor number, cell viability and real-time monitoring of cell status. As cancer predominantly spreads through the blood and lymphatic system, the potential ability to molecularly image cancer cells in metastatic carcinoma without incision and with microdose amounts of safe, non-toxic, multifunctional nanoparticles will have a significant impact on the standard of diagnosis and therapy for many cancers. The low cytotoxicity of these nanocomplexes and their therapeutic efficacy could be potentially beneficial in the study of deep organ metastatic carcinoma in animal models.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the funding support provided by the Baylor College of Medicine faculty startup and seed grant funding to Dr. Joshi. Rizia Bardhan and N. J. Halas were supported by Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1220), and Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (W911NF-04-01-0203). We also thank Prof. Jeffrey G. Jacot (Assistant Professor, Department of Bioengineering, Rice University and Division of Congenital Heart Surgery, Texas Children’s Hospital) and Jackson Myers (graduate student, Rice University) for the use of the fluorescence microscope. We thank Dr. Xiande Liu who is a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine for providing valuable help and discussions.

Abbreviations List

- HER

The human epidermal growth factor receptor

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NIR

Near infrared

- AOC

Advanced ovarian cancer

- FIGO

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- AMF

Alternating magnetic fields

- hNP

Hybrid nanoparticle

- OI

Optical imaging

- SPIO

Superparamagnetic iron oxide

- ICG

Indocyanine green

- EPR

The enhanced permeability and retention

- APTES

(3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane

- NS@Fe3O4

the Fe3O4 nanoparticles

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- MPTES

(3-mercaptopropyl) triethoxysilane

- TMB

3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- NGS

Normal Goat Serum

- RARE

Rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement

- PI

Propidium iodide

- NS

Au Nanoshells

- MIP

The maximum intensity projections

Footnotes

Bardhan R, Chen W, Perez-Torres C, et al. Nanoshells with targeted simultaneous enhancement of magnetic and optical imaging and photothermal therapeutic response. Advanced Functional Materials, 2009; in press.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, et al. Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:389–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark TG, Stewart ME, Altman DG, Gabra H, Smyth JF. A prognostic model for ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:944–52. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilleri-Broët S, Hardy-Bessard AC, Le Tourneau A, et al. HER-2 overexpression is an independent marker of poor prognosis of advanced primary ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter study of the GINECO group. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:104–12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimova I, Zaharieva B, Raitcheva S, Dimitrov R, Doganov N, Toncheva D. Tissue microarray analysis of EGFR and erbB2 copy number changes in ovarian tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felip E, Del Campo JM, Rubio D, Vidal MT, Colomer R, Bermejo B. Overexpression of c-erbB-2 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Prognostic value and relationship with response to chemotherapy. Cancer. 1995;75:2147–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2147::aid-cncr2820750818>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høgdall EV, Christensen L, Kjaer SK, et al. Distribution of HER-2 Overexpression in Ovarian Carcinoma Tissue and Its Prognostic Value in Patients with Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:66–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross JS, Yang F, Kallakury BV, Sheehan CE, Ambros RA, Muraca PJ. HER-2/neu oncogene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization in epithelial tumors of the ovary. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:311–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton TC, Young RC, McKoy WM, et al. Characterization of a Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cell Line (NIH: OVCAR-3)1 with Androgen and Estrogen Receptors. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5379–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellström I, Goodman G, Pullman J, Yang Y, Hellström KE. Overexpression of HER-2 in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2420–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy JR. The future of theranostic nanoagents. Nanomed. 2009;4:693–5. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771–82. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, et al. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13549–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2115–20. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skrabalak SE, Au L, Lu X, Li X, Xia Y. Gold nanocages for cancer detection and treatment. Nanomed. 2007;2:657–68. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Xiong C, Zhang G, et al. Targeted photothermal ablation of murine melanomas with melanocyte-stimulating hormone analog-conjugated hollow gold nanospheres. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:876–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loo C, Lin A, Hirsch L, et al. Nanoshell-enabled photonics-based imaging and therapy of cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2004;3:33–40. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Near-infrared resonant nanoshells for combined optical imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1929–34. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loo C, Lowery A, Halas N, West J, Drezek R. Immunotargeted nanoshells for integrated cancer imaging and therapy. Nano Lett. 2005;5:709–11. doi: 10.1021/nl050127s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilger I, Hergt R, Kaiser WA. Use of magnetic nanoparticle heating in the treatment of breast cancer. IEE Proc Nanobiotechnol. 2005;152:33–9. doi: 10.1049/ip-nbt:20055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy JR, Jaffer FA, Weissleder R. A Macrophage-Targeted Theranostic Nanoparticle for Biomedical Applications. Small. 2006;2:983–7. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan D, Caruthers SD, Hu G, et al. Ligand-Directed Nanobialys as Theranostic Agent for Drug Delivery and Manganese-Based Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Vascular Targets. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9186–7. doi: 10.1021/ja801482d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy GR, Bhojani MS, McConville P, et al. Vascular Targeted Nanoparticles for Imaging and Treatment of Brain Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6677–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasongkla N, Bey E, Ren J, et al. Multifunctional Polymeric Micelles as Cancer-Targeted, MRI-Ultrasensitive Drug Delivery Systems. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2427–30. doi: 10.1021/nl061412u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagalkot V, Zhang L, Levy-Nissenbaum E, et al. Quantum Dot-Aptamer Conjugates for Synchronous Cancer Imaging, Therapy, and Sensing of Drug Delivery Based on Bi-Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3065–70. doi: 10.1021/nl071546n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldenburg SJ, Averitt RD, Westcott SL, Halas N. Nanoengineering of optical resonances. Chem Phys Lett. 1998;288:243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi MR, Stanton-Maxey KJ, Stanley JK, et al. A Cellular Trojan Horse for Delivery of Therapeutic Nanoparticles into Tumors. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3759–65. doi: 10.1021/nl072209h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bardhan R, Grady NK, Halas NJ. Nanoscale control of near infrared fluorescence enhancement using Au nanoshells. Small. 2008;4:1716–22. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release. 2000;65:271–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melancon MP, Lu W, Yang Z, et al. In vitro and in vivo targeting of hollow gold nanoshells directed at epidermal growth factor receptor for photothermal ablation therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1730–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stober W, Fink A, Bohn EJ. Controlled growth of mono-disperse silica spheres in the micron size range. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1968;26:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duff DG, Baiker A, Edwards PP. A new hydrosol of gold clusters. 1. Formation and particle size variation. Langmuir. 1993;9:2301–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang YS, Risbud S, Rabolt JF, Stroeve P. Synthesis and characterization of nanometer–size Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 particles. Chem Mater. 1996;8:2209–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampath L, Kwon S, Ke S, et al. Dual-labeled trastuzumab-based imaging agent for the detection of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression in breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1501–10. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang YF, Lin YW, Lin ZH, Chang HT. Aptamer-modified gold nanoparticles for targeting breast cancer cells through light scattering. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11:775–83. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finn RS, Dering J, Ginther C, et al. Dasatinib, an orally active small molecule inhibitor of both the src and abl kinases, selectively inhibits growth of basal-type/“triple-negative” breast cancer cell lines growing in vitro. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105:319–26. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;17:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sotiriou C, Neo SY, McShane LM, et al. Breast cancer classification and prognosis based on gene expression profiles from a population-based study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10393–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732912100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tseng PH, Wang YC, Weng SC, et al. Overcoming trastuzumab resistance in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells by using a novel celecoxib-derived phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 inhibitor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1534–41. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray-Coquard I, Guastalla JP, Allouache D, et al. HER2 Overexpression/amplification and trastuzumab treatment in advanced ovarian cancer: a GINECO phase II study. Clincal Ovarian Cancer. 2008;1:54–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reese DM, Slamon DJ. HER-2/neu Signal Transduction in Human Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Stem Cells. 1997;15:1–8. doi: 10.1002/stem.150001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia Enables Tumor-specific Nanoparticle Delivery: Effect of Particle Size. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Characterization of the Effect of Hyperthermia on Nanoparticle Extravasation from Tumor Vasculature. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3027–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]