Abstract

Importance

Our understanding of how mental and physical disorders are associated and contribute to health outcomes in populations depends on accurate ascertainment of the history of these disorders. Recent studies have identified substantial discrepancies in the prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents and young adults depending on whether the estimates are based on retrospective reports or multiple assessments over time. It is unknown whether such discrepancies are also seen in mid to late life. Furthermore, no previous studies have compared lifetime prevalence estimates of common physical disorders such as diabetes and hypertension ascertained by prospective cumulative estimates vs. retrospective estimates.

Objective

To examine the lifetime prevalence estimates of mental and physical disorders during mid to late life using both retrospective and cumulative evaluations.

Design

Prospective population-based survey with 4 waves of interviews.

Setting

Community residents in Baltimore City, Maryland.

Participants

Volunteers who participated in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Survey wave 1 (1981) through wave 4 (2004) follow-up data (N = 1,071).

Main outcome measures

Lifetime prevalence of selected mental and physical disorders at wave 4 (2004), according to both retrospective data and cumulative evaluations based on 4 interviews from wave 1 to wave 4.

Results

Retrospective evaluations substantially underestimated the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders as compared with cumulative evaluations. The lifetime prevalence estimates ascertained by retrospective and cumulative evaluations were 4.5% vs. 13.1%, respectively, for major depression, 0.6% vs. 7.1% for obsessive-compulsive disorder, 2.5% vs. 6.7% for panic disorder, 12.6% vs. 25.3% for social phobia, 9.1% vs. 25.9% for alcohol abuse/dependence, and 6.7% vs. 17.6% for drug abuse/dependence. In contrast, retrospective lifetime prevalence estimates of physical disorders ascertained at wave 4 were much closer to those based on cumulative data from all 4 waves. The prevalence estimates ascertained by the two methods were 18.2% vs. 20.2%, respectively, for diabetes, 48.4% vs. 55.4% for hypertension, 45.8% vs. 54.0% for arthritis, 5.5% vs. 7.2% for stroke, and 8.4% vs. 10.5% for cancer.

Conclusions and Relevance

One-time, cross-sectional population surveys may consistently underestimate the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders. The population burden of mental disorders may, therefore, be substantially higher than previously appreciated.

A common approach to estimating the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in population surveys is to ask participants to retrospectively recall any episodes of illness that they may have experienced over their entire lifetime.1-8 Lifetime prevalence estimates, however, are potentially susceptible to recall bias and other memory distortions. With regard to depressive symptoms, for example, diminishing recall of past symptoms with time has been reported in a number of studies.9-12 Retrospective evaluation may thus substantially underestimate or overestimate the true lifetime prevalence of mental disorders. Recently Moffit and colleagues13 examined the potential impact of recall bias in epidemiologic studies by comparing estimates based on one-time retrospective reports and those based on reports over multiple interviews in the same cohort. They found that lifetime prevalence estimates based on cumulative reports were approximately two times higher than those based on retrospective data for a number of common mental disorders including major depression, anxiety disorders and alcohol/drug dependence. In another study, Regier and colleagues 14 found that lifetime prevalence estimates of major mental disorders based on the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study obtained just one year apart (at waves 1 and 2) were 8% higher when estimates were based on combined data from both waves, compared to wave 1 only. Likewise, Copeland et al. 15 reported underestimation of mental disorders at any given time as compared with prospective cumulative evaluation. Olino et al.16 found higher lifetime prevalence estimates of several mental disorders ascertained prospectively compared to estimates based on siblings’ retrospective reports. Studies by Moffit et al., Copeland et al. and Olino et al.,13,15,16 however, were based on cohorts of children, adolescents and young adults, rather than adults of all ages. Furthermore, the Regier et al. 14 study compared estimates based on one wave to those based on two waves conducted 1 year apart. To the best of our knowledge, besides depression or depressive symptoms, 9-12 no previous studies have examined whether the lifetime prevalence estimates of common mental disorders based on retrospective reports in mid to late life are underestimated when compared to cumulative reports based on multiple interviews conducted over a longer period of time. Furthermore, no previous studies have compared lifetime prevalence estimates of common physical disorders such as diabetes and hypertension ascertained by retrospective report vs. cumulative reports over an extended period. Therefore, it is unknown whether lifetime prevalence estimates of common mental disorders in middle-aged or older adults or physical disorders are underestimated in one-time retrospective evaluation as compared with cumulative evaluation using multiple interviews. Given the significant burden imposed by mental and physical disorders, it is important to examine how accurately surveys can estimate their prevalence. It is also important to study the accuracy of retrospective reports over the adult lifespan extending into middle- and older age, because individuals experiencing long intervals between episodes of illness may be especially prone to forgetting past health problems. Furthermore, among older adults, these errors may be exacerbated by cognitive decline.

We used data from the Baltimore ECA Follow-up study waves 1 (1981) through 4 (2004-2005) to compare the lifetime prevalence of mental and physical disorders based on retrospective reports (from wave 4 only) vs. cumulative reports (from all waves). The wave 4 sample consisted of middle-aged and older adults. We also assessed factors associated with the under-reporting of lifetime history of disorders at wave 4.

METHODS

Sample

The Baltimore ECA Follow-Up Study is a longitudinal, population-based cohort of adults originally interviewed in 1981 (wave 1, N = 3,481) and followed-up in 1982 (wave 2, N = 2,768), 1993-1996 (wave 3, N = 1,920), and 2004-2005 (wave 4, N = 1,071). The ECA was designed to collect data on the prevalence and incidence of mental disorders in an adult community sample according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III, for waves 1 and 2) or the DSM-III-Revised (DSM-III-R, for waves 3 and 4). Methods for the Baltimore ECA Follow-Up Study have been described in detail elsewhere.17 Of the original 3,481 participants originally interviewed in 1981, 2031 survived to 2004-2005 and 1071 participated in the wave 4 interview (53% of survivors). Of the 960, who did not participate in the wave 4 interview, 436 refused to participate and 524 were lost to follow-up. The primary reason for the loss of contact is change in residence. Those who refused to participate were older, more likely to be Caucasian, and had lower education than those who participated. Those who were lost to follow-up were more likely to be Non-Caucasian, had lower education, and were more likely to have cognitive impairment at baseline than those who participated. Attrition analysis in the Baltimore ECA has been detailed previously. 17 The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Assessments

At each wave, trained interviewers administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS),18 a structured interview that yields psychiatric diagnoses based on DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria. At waves 1 and 2, the DIS version III19 (based on DSM-III criteria) was used; at waves 3 and 4, the DIS version III-R20 (based on DSM-III-R criteria) was used. At each wave, lifetime history of the following six mental disorders was evaluated and used for the present analysis: major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, social phobia, alcohol abuse or dependence, and drug (including cocaine, marijuana, stimulants, sedatives, and tranquilizers) abuse or dependence. These disorders were evaluated at all waves; other mental disorder including schizophrenia/bipolar disorder which were evaluated at waves 1 and 2, or simple phobia that was examined at waves 1 through 3, but these mental disorders were not included in later waves, and were therefore excluded from this study. In our study “lifetime diagnosis” at a visit includes both current episode and past episode(s) reported in the interview at that visit. Failure to recall lifetime mental disorders was defined as not meeting criteria for the lifetime history of the mental disorder at wave 4 despite reporting symptoms that met criteria for that disorder at one or more previous waves. Global cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).21

At each wave, participants were also asked if they had ever had the following physical illnesses: diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, stroke and cancer (any type). Sociodemographic characteristics included in the analyses were based on wave 4 reports and included age at wave 4 (≤49, 50–59, and ≥60 years), sex, race (Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian, which included African American, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islanders), educational attainment (<12 years vs. ≥12 years), marital status (married vs. not married), and employment status. Mental health service use (≥1 visit within the 6-month period prior to the wave 4 interview vs. 0 visits within the past 6 months) was also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Lifetime prevalence was estimated using the assessments of lifetime disorders at each wave over waves 1 through 4 (prospective cumulative method), and compared to the lifetime prevalence based solely on the assessment of lifetime disorders at wave 4 (cross-sectional retrospective method). Cumulative prevalence of mental and physical disorders was defined as; the sum of the participants who met the criteria at least once in previous and current interviews. Confidence intervals were calculated for each prevalence estimate. We first compared retrospective and cumulative lifetime prevalence of mental and physical disorders by the conservative method of examining the overlap of confidence intervals. 22

We also compared the two prevalence estimates using McNemar test, which is appropriate for comparing dichotomous responses within the same individual. 23 In further analyses, we also calculated the cumulative prevalence of mental disorders excluding participants who had an MMSE score lower than 24, to determine whether cognitive decline accounted for results. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with failure to recall mental disorders at wave 4. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Sensitivity analysis

Because different versions of diagnostic criteria for mental disorders were used for waves 1-2 (DSM-III) and waves 3-4 (DSM-III-R), we compared a) cumulative prevalence of mental disorders based on waves 1-2 and retrospective lifetime prevalence at wave 2, and b) cumulative prevalence of mental disorders based on waves 3-4 and retrospective lifetime prevalence at wave 4, to see whether differences in diagnostic criteria may have affected results.

RESULTS

Demographics

Participants had a mean (± standard deviation) age of 35.4 ± 12.9 years at wave 1 and, and 58.9 ± 12.9 years at wave 4. Approximately 37% (397/1,071) were male, 62% (662/1,071) were Caucasian, 35 % (374/1,071) were African American, and 3% (33/1,071) were from other race/ethnicity; 54% (581/1,071) were married at the wave 4 interview. The mean educational attainment was 12.4 ± 2.8 years. Employment status at wave 4 interview was reported by 96% (1,028 / 1071) of participants; approximately 59% (605/1,028) were employed, 18% (196/1,028) were keeping house, 14% (146/1,028) were retired, and 8% (81/1,028) were unemployed or disabled. Among 1,071 participants, 947 (88%) completed the MMSE at wave 4. Participants’ mean MMSE score was 28.1 ± 3.1, and 50 (5%) had an MMSE score <24. Of the 1,071 participants, 129 (12%) had used a mental health service within 6 months prior to wave 4 interview.

Wave 4 retrospective lifetime prevalence estimates vs. cumulative four-wave estimates of mental and physical disorders

The lifetime prevalence estimates of mental and physical disorders, according to the cross-sectional retrospective method are presented for each wave in Table 1. For the most part, the prevalence of mental disorders did not systematically vary across the years, even as respondents aged and had more years of exposure to the risk of disorder. In contrast, the prevalence of physical conditions increased with the aging of the cohort.

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of mental and physical disorders at each wave in 1,071 participants of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, based on cross-sectional retrospective evaluation.

| Wave 1 (1981) | Wave 2 (1982) | Wave 3 (1993) | Wave 4 (2004) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental disorders | ||||

| Major depression, N (%) | 61 (5.8) | 28 (2.9) | 67 (6.5) | 46 (4.5) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 11 (1.1) | 48 (4.7) | 20 (2.0) |

| OCD, N (%) | 49 (4.6) | 32 (3.3) | 11 (1.1) | 6 (0.6) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 17 (1.7) | 6 (0.6) | 2 (0.2) |

| Social phobia, N (%) | 42 (4.0) | 15 (1.5) | 177 (16.8) | 129 (12.6) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 10 (1.0) | 157 (14.9) | 62 (6.0) |

| Panic disorder, N (%) | 18 (1.7) | 16 (1.6) | 29 (2.8) | 26 (2.5) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 13 (2.0) | 25 (2.4) | 16 (1.6) |

| Drug abuse/dependence, N (%) | 79 (7.5) | 64 (6.6) | 84 (8.2) | 63 (6.7) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 37 (3.8) | 48 (4.7) | 24 (2.6) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence, N (%) | 124 (11.7) | 91 (10.2) | 152 (14.5) | 94 (9.1) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 25 (2.8) | 90 (8.6) | 39 (3.8) |

| Physical disorders | ||||

| Diabetes, N (%) | 36 (3.4) | 19 (1.8) | 95 (8.9) | 195 (18.2) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 6 (0.6) | 68 (6.5) | 106 (9.9) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 210 (19.6) | 122 (12.5) | 306 (28.6) | 518 (48.4) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 19 (1.9) | 150 (14.2) | 214 (20.0) |

| Arthritis, N (%) | 169 (15.8) | 147 (15.1) | 296 (27.6) | 490 (45.8) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 39 (4.0) | 154 (14.6) | 216 (20.2) |

| Stroke, N (%) | 7 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) | 21 (2.0) | 59 (5.5) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 1 (0.1) | 16 (0.2) | 53 (5.0) |

| Cancer, N (%) | 27 (2.5) | 5 (0.5) | 57 (5.3) | 90 (8.4) |

| New cases at waves 2-4, N (%) | - | 1 (0.1) | 34 (3.3) | 50 (4.7) |

| Total N | 1071 | 1071 | 1071 | 1071 |

Note: OCD stands for obsessive compulsive disorder.

The number of evaluation missing ranges from 0 (0%) to 13 (1.2%), from 96 (9%) to 175 (16.3%), from 17 (1.6%) to 46 (4.3%), and from 4 (0.4%) to 131 (12.2%), for waves 1 - 4, respectively.

DSM-III criteria were used for waves 1 and 2, whereas DSM-III-R criteria were used for waves 3 and 4.

In analyses of mental disorders, the wave 4 lifetime prevalence estimates according to the cross-sectional retrospective method were markedly lower than estimates based on the prospective cumulative lifetime data from all 4 waves as shown by non-overlapping 95% CIs, as well as the results of McNemar test (Table 2). The lifetime prevalence estimates ascertained by these two methods were 4.5% vs. 13.1%, respectively, for major depression, 0.6% vs. 7.1% for OCD, 2.5% vs. 6.7% for panic disorder, 12.6% vs. 25.3% for social phobia, 9.1% vs. 25.9% for alcohol abuse/dependence, and 6.7% vs. 17.6% for drug abuse/dependence. The ratios of wave 4 over cumulative prevalence estimates ranged from 2 to 12, indicating 2 to 12 fold differences among the two estimates.

Table 2.

Comparison of lifetime prevalence of mental and physical disorder in Wave 4 and cumulative four waves interviews (N = 1071)

| Lifetime prevalence based on Wave 4 | Cumulative lifetime prevalence based on four waves of interviews (1981 – 2005) | Comparison using McNemar testa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%, 95%CI) | N (%, 95%CI) | Chi-square | P | |

| Mental disorders | ||||

| Major depression | 46 (4.5, 3.2 - 5.8) | 140 (13.1, 11.1 - 15.1) | 85.01 | <0.001 |

| OCD | 6 (0.6, 0.1 - 1.1) | 76 (7.1, 5.6 - 8.6) | 64.02 | <0.001 |

| Panic disorder | 26 (2.5, 1.6 - 3.5) | 72 (6.7, 5.2 - 8.2 ) | 43.02 | <0.001 |

| Social phobia | 129 (12.6, 10.5 - 14.6) | 271 (25.3, 22.7 - 27.9) | 120.01 | <0.001 |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 63 (6.7, 5.4 - 8.7) | 188 (17.6, 15.3 - 19.8) | 111.01 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 94 (9.1, 7.3 - 10.9) | 277 (25.9, 23.2 - 28.5) | 177.01 | <0.001 |

| Physical disorders | ||||

| Diabetes | 195(18.2, 16.0 - 21.0) | 216 (20.2, 17.8 - 22.6) | 19.05 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 518 (48.4, 45.5 - 51.6) | 593 (55.4, 52.4 - 58.4) | 72.01 | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 490 (45.8, 42.9 - 48.9) | 578 (54.0, 51.0 - 57.0) | 86.01 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 59 (5.5, 4.2 - 6.9) | 77 (7.2, 5.6 - 8.7) | 16.06 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 90 (8.4, 6.8 - 10.1) | 112 (10.5, 8.6 - 12.3) | 19.05 | <0.001 |

Participants who missed the evaluation at wave 4 interview were excluded.

Note: CI stands for confidence interval, OCD stands for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

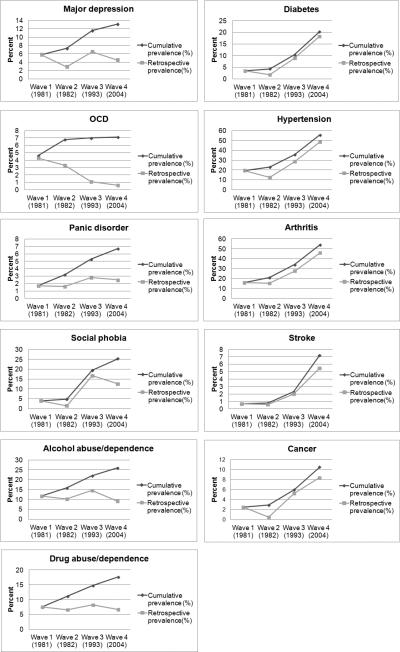

In contrast, retrospective lifetime prevalence estimates of physical disorders ascertained at wave 4 were much closer to those based on cumulative data from all 4 waves. The ratios of wave 4 over cumulative prevalence estimates ranged from 1.1 to 1.3. However, the 95% CIs for the retrospective prevalence and cumulative prevalence of hypertension and arthritis did not overlap, indicating that retrospective lifetime prevalence were lower than cumulative lifetime prevalence for these disorders. These findings were corroborated by McNemar tests which indicated significantly higher lifetime cumulative prevalence estimates across all physical disorders. The prevalence estimates ascertained by the two methods were 18.2% vs. 20.2%, respectively, for diabetes, 48.4% vs. 55.4% for hypertension, 45.8% vs. 54.0% for arthritis, 5.5% vs. 7.2% for stroke, and 8.4% vs. 10.5% for cancer (Table 2). Figure 1 presents cumulative prevalence and retrospective lifetime prevalence of mental and physical disorders at each wave (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative vs. retrospective lifetime prevalence of mental (left) and physical (right) disorders at each wave (%). OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Excluding participants with an MMSE score <24 did not meaningfully change the results. After excluding these participants, the retrospective vs. prospective lifetime prevalence was 3.8% vs. 12.8% for major depression, 0.7% vs. 7.0% for OCD, 2.4% vs. 6.6% for panic disorder, 14.5% vs. 27.1% for alcohol abuse/dependence, and 6.7% vs. 19.4% for drug abuse/dependence, respectively.

Characteristics associated with failure to recall history of mental disorder

Among participants with a lifetime history based on prospective cumulative evaluation across 4 waves, 94 (67%), 70 (92%), 46 (64%), 183 (66%), and 125 (66%) did not meet the criteria for MDD, OCD, panic disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, and drug abuse/dependence, respectively at the wave 4 retrospective evaluation. Compared to participants aged ≤49 years, participants aged ≥60 years had a greater odds of failing to recall lifetime history of MDD (odds ratio [OR]; 6.7, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 - 29.1), panic disorder (OR; 14.4, 95% CI, 2.0 - 106.4), alcohol abuse/dependence (OR; 16.4, 95% CI, 5.6 – 48.5) and drug abuse/dependence (OR; 22.6, 95% CI, 2.2 – 233.0) (Table 3). Participants aged 50-59 years also had a greater odds of failing to recall panic disorder (OR; 5.4, 95% CI, 1.4 - 20.2) and alcohol abuse/dependence (OR; 1.9, 95% CI, 1.1 - 3.6) at wave 4. Higher educational attainment (12+ years vs. <12 years) correlated with greater risk of underreporting of social phobia (OR; 3.1, 95% CI, 1.6 – 5.9). In contrast, visits to a mental health professional within the 6 months prior to the wave 4 interview were associated with a lower likelihood of recall failure of OCD at wave 4 (OR; 0.04, 95% CI, 0.0-0.7). Being disabled or unemployed at wave 4 was negatively associated with recall failure of social phobia (OR; 0.3, 95% CI, 0.1-0.9). None of the other socio-demographic characteristics were associated with failure to recall past mental disorder episodes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of failure of recall at previously reported lifetime history of mental disorders at wave 4 interview.

| Mental disorder | Predictor | OR for failure of recall | 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Major depression | Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 50 - 59 years old | 2.01 | 0.85 | 4.75 | |

| 60+ years old | 6.69* | 1.54 | 29.06 | |

| Male sex (female) | 2.19 | 0.79 | 6.10 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 0.71 | 0.29 | 1.74 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 1.50 | 0.46 | 4.93 | |

| Married (not married) | 0.76 | 0.34 | 1.72 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.46 | 0.18 | 1.14 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 0.91 | 0.26 | 3.26 | |

| Keeping house | 2.42 | 0.77 | 7.68 | |

| Retired | - | - | - | |

| OCD | Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 50 - 59 years old | 18.43 | 0.88 | 385.15 | |

| 60+ years old | 1.90 | 0.05 | 70.44 | |

| Male sex (female) | 1.56 | 0.10 | 24.55 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 0.45 | 0.04 | 4.97 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 1.35 | 0.07 | 27.13 | |

| Married (not married) | 3.29 | 0.18 | 60.45 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.04* | 0.00 | 0.68 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 0.44 | 0.02 | 8.89 | |

| Keeping house | 1.35 | 0.06 | 32.47 | |

| Retired | - | - | - | |

| Panic disorder | Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 50 - 59 years old | 5.38* | 1.43 | 20.21 | |

| 60+ years old | 14.42* | 1.96 | 106.36 | |

| Male sex (female) | 1.83 | 0.33 | 9.96 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 1.14 | 0.30 | 4.34 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 0.80 | 0.20 | 3.21 | |

| Married (not married) | 1.48 | 0.43 | 5.10 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.49 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 1.68 | 0.37 | 7.62 | |

| Keeping house | 1.01 | 0.22 | 4.68 | |

| Retired | - | - | - | |

| Social phobia | Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 50 - 59 years old | 0.74 | 0.37 | 1.47 | |

| 60+ years old | 1.21 | 0.54 | 2.73 | |

| Male sex (female) | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.83 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 0.87 | 0.49 | 1.54 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 3.07* | 1.60 | 5.87 | |

| Married (not married) | 1.54 | 0.87 | 2.73 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.58 | 0.27 | 1.25 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 0.32* | 0.11 | 0.93 | |

| Keeping house | 0.53 | 0.24 | 1.18 | |

| Retired | 1.21 | 0.44 | 3.33 | |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | ||||

| Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| 50 - 59 years old | 1.94* | 1.05 | 3.60 | |

| 60+ years old | 16.41* | 5.56 | 48.48 | |

| Male sex (female) | 0.75 | 0.39 | 1.43 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 1.33 | 0.70 | 2.50 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 1.24 | 0.65 | 2.35 | |

| Married (not married) | 1.85* | 1.02 | 3.33 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.97 | 0.43 | 2.20 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 0.85 | 0.32 | 2.25 | |

| Keeping house | 0.70 | 0.24 | 2.07 | |

| Retired | 0.33 | 0.11 | 1.02 | |

| Drug abuse/dependence | ||||

| Age (− 49 years old) | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| 50 - 59 years old | 1.87 | 0.89 | 3.91 | |

| 60+ years old | 22.64* | 2.20 | 232.96 | |

| Male sex (female) | 0.59 | 0.28 | 1.28 | |

| Caucasian (minority racial ethnic group ) | 1.21 | 0.55 | 2.63 | |

| 12 + years education (−11 years) | 2.04 | 0.92 | 4.50 | |

| Married (not married) | 1.65 | 0.82 | 3.34 | |

| Any mental health visit within 6 months (no visit) | 0.51 | 0.21 | 1.27 | |

| Employed | 1.0 (ref) | |||

| Not employed or disabled | 0.66 | 0.21 | 2.10 | |

| Keeping house | 0.93 | 0.31 | 2.76 | |

| Retired | 0.23 | 0.04 | 1.22 | |

Note: OR stands for odds ratios obtained in multivariable logistic regression, CI stands for confidence interval, OCD stands for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

p < 0.05.

Sensitivity analysis

In the comparison of lifetime prevalence of mental disorders using retrospective data from wave 2 with cumulative data from waves 1 and 2, retrospective data consistently underestimated the prevalence of all mental disorders studied; retrospective estimates from ranging 1.2 to 3.1 times lower than cumulative prevalence (Supplemental Table 1). Similarly, estimates of lifetime prevalence of mental disorders obtained retrospectively at wave 4 were 1.6 to 2.7 times lower than estimates of based on cumulative prevalence using data from waves 3 and 4 (Supplemental Table 2).

COMMENTS

We found that estimates of the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders were 2 to 12 times lower when based on cross-sectional retrospective reports from a single interview compared to estimates based on cumulative reports from multiple interviews. This was true for the range of disorders we studied. This finding corroborates previous research comparing lifetime prevalence estimates based on one retrospective interview with those based on multiple interviews.13,15,16 Past studies, however, were mainly based on samples of children, adolescents and young adults. Findings from the present study indicate that failure to recall lifetime episodes of mental disorders is not limited to this age range and extends to midlife, when mental disorders are most prevalent,24 and to older adulthood.

The lifetime prevalence estimates of common physical disorders presented a strong contrast in that they did not differ meaningfully between the two ascertainment methods. The contrast between recall of mental and physical disorders is noteworthy and may be attributable to differences in assessment, age of onset and course of these disorders. While ascertainment of mental disorders in our study was based on symptom criteria (i.e., endorsement of a certain number of symptoms from various categories), ascertainment of physical illnesses was based on a participant's report of presence vs. absence of a particular physical disorder (e.g., diabetes, hypertension). Furthermore, many of the mental disorders assessed in this study have an early age of onset and a course characterized by remission and relapse, whereas the medical conditions assessed are typically illnesses of middle and older age and tend to have a chronic, non-remitting course. These differences can partly explain variations in recall. The results of our logistic regression analyses support these conclusions; older participants were less likely to recall past psychiatric episodes, whereas participants with recent mental health visits were more likely to recall past psychiatric episodes. Mental disorders have a lower point- and 1-year prevalence in older age groups 1,2,25 and participants who are currently in treatment are more likely to meet criteria for current mental illness. Besides simply forgetting previous episodes, positive reframing of past episodes based on current circumstances may also lead to recall failure. 26 Finally, mental disorders are still associated with a substantial level of stigma, 27 potentially leading to less willingness to disclose psychiatric symptoms. The level of stigma may be evolving over calendar time, with less stigma now than earlier times, leading older individuals to be less likely to recall or report symptoms than younger individuals, contributing to the failure of recall.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has compared the lifetime prevalence estimates of both mental and physical illnesses using retrospective and prospective approaches across the adult lifespan. The study also extends past research comparing estimates in adolescents and young adult samples13,16 or limited to depression.9-12 In our study, subjects were followed from an average age of 35 ± 13 to 59 ± 13 years and we evaluated several mental disorders. Nevertheless, our results are similar to those of the study by Moffit et al.13 who showed higher lifetime prevalence estimates of psychiatric diagnoses across ages 18 to 32 years, compared to retrospective assessments. Taken together, these studies raise doubts about the validity of lifetime prevalence estimates of mental disorders obtained in retrospective population surveys. Given the results of the present study, the true lifetime prevalence of mental disorders may be considerably higher than those reported based on retrospective data - particularly in studies of middle-aged and older adults. The findings also suggest that surveys with a retrospective evaluation of mental disorders may not be appropriate for etiological research on the mental disorders as many individuals with lifetime history of such disorders would be misclassified as negative cases.

The estimates of lifetime prevalence of mental disorders ascertained by multiple interviews in this study are lower than those of the studies Moffitt et al. or Olino et al. 13,16 For instance, in our study the lifetime the prevalence of MDD was estimated at 13% compared to 41% in Moffitt and colleagues’ study. Several factors may be contributing to this discrepancy, including differences in age and racial distribution of the samples and assessment instruments. Alternatively, we may have missed a substantial amount of information related to mental disorders before age 35—the average age of the ECA sample at baseline. Thus, even the cumulative ECA data may have underestimated the true lifetime prevalence of many mental disorders, especially those with early ages of onset.

It might be plausible that the association of failure to recall past psychiatric symptoms with older age demonstrated in this study is due to the influence of cognitive decline, since older age is one of the major risk factors of cognitive decline. However, excluding subjects with MMSE score lower than 24 did not change our conclusions. In addition, we also entered MMSE score as a continuous variable and, separately, as a discrete variable (MMSE score < 24 vs. 24 or higher) in the regression analyses. In these analyses, MMSE scores did not predict recall failure of any mental disorders (data not shown). Therefore the correlation of older age and recall failure of psychiatric symptoms may be due to factors other than significant cognitive decline. However, as reported in our previous study, 17 cognitive impairments at baseline was associated with loss to follow-up, therefore participants of this study may be less cognitively impaired than a random sample of same age general population. In addition, since 12% of participants in this study did not complete the MMSE evaluation, it might be possible that we have underestimated the impact of cognitive impairment on recall. On the other hand, more sensitive measures of cognitive impairment might reveal a contribution of cognitive decline to failure to recall past episodes of mental disorders.

In our study, lifetime prevalence estimates of mental disorders were defined by meeting the diagnostic criteria at any time over the lifetime. Therefore, any discrepancy between cumulative diagnoses and the wave 4 retrospective cross-sectional diagnoses would, by definition, indicate lack of accuracy of wave 4 diagnosis, suggesting that prevalence estimates of mental disorders in retrospective data may be less accurate than cumulative data. Recall of mental disorders can be affected by many factors such as aging, stigma, and interaction with a mental health professional as discussed above. Also it might be possible that recency, chronicity or severity of illness could affect recall although we were not able to assess the impact of these latter factors in this study. However, unemployment/disability, which is associated with severity of mental health conditions was associated with lower likelihood of failure to recall of some mental disorders, as was recent mental health contact which may be associated with the recency of mental health problems. Since we used participants’ employment status at wave 4 interview, it is possible that recent mental illness episodes at wave 4 would be associated more strongly with both recall of such episodes and unemployment or disability status at this wave.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, the ECA study used different versions of DSM criteria for waves 1-2 and waves 3-4 although our sensitivity analysis similarly showed differences between wave 2 estimates and waves 1 and 2 cumulative estimates and between wave 4 estimates and waves 3 and 4 cumulative estimates. Second, it did not include all mental disorders. In particular, we were unable to assess several anxiety disorders which tend to have a recurrent or chronic course (e.g., diabetes and arthritis), because they were not assessed in all waves. Likewise, we were not able to assess physical illnesses with early onset, and an episodic nature, such as asthma, infectious diseases, or head injury. Future studies should include such episodic, remitting physical conditions to examine whether these attributes could explain differences in recall with mental disorders. Third, further analyses may be needed to compare participants who consistently recalled mental disorders in all four waves and those do not; however, the modest sample size of this study did not permit such analyses. Fourth, since we limited our samples to participants who were interviewed at both waves 1 and 4, this selective attrition would impact representativeness and external validity of our results, although it would not impact the internal validity of our findings. Finally, as discussed above, we were unable to consider the duration, the severity, or the time since the last episode of mental and physical disorders despite past studies demonstrating an association between these factors and recall of past symptoms.10-12 It is also important to examine whether mental or physical health crises differently affect recall of mental disorders and physical disorders, but health crisis data were not available in the ECA. All of these issues should be investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, and in the context of these limitations, the results of our study raise questions about the accuracy of lifetime prevalence estimates of mental disorders in general population surveys based on a single retrospective recall. When comparing cumulative reports over multiple waves and cross-sectional reports of medical conditions, self-reports of lifetime mental disorders may grossly underestimate the true lifetime prevalence of mental disorders.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIDA grant DA026652.

Dr. Spira is supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award (1K01AG033195) from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Takayanagi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the united states. results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade L, Walters EE, Gentil V, Laurenti R. Prevalence of ICD-10 mental disorders in a catchment area in the city of sao paulo, brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(7):316–325. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The christchurch health and development study: Review of findings on child and adolescent mental health. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(3):287–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the united states: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the united states: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, et al. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1997–2010. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson R, Bogner HR, Coyne JC, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW. Personal characteristics associated with consistency of recall of depressed or anhedonic mood in the 13-year follow-up of the baltimore epidemiologic catchment area survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(5):345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells JE, Horwood LJ. How accurate is recall of key symptoms of depression? A comparison of recall and longitudinal reports. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):1001–1011. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews G, Anstey K, Brodaty H, Issakidis C, Luscombe G. Recall of depressive episode 25 years previously. Psychol Med. 1999;29(4):787–791. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Bulloch AG, D'Arcy C, Streiner DL. Recall of recent and more remote depressive episodes in a prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(5):691–696. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med. 2010;40(6):899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: A prospective cohort analysis from the great smoky mountains study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(3):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olino TM, Shankman SA, Klein DN, et al. Lifetime rates of psychopathology in single versus multiple diagnostic assessments: Comparison in a community sample of probands and siblings. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(9):1217–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton WW, Kalaydjian A, Scharfstein DO, Mezuk B, Ding Y. Prevalence and incidence of depressive disorder: The baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981-2004. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(3):182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule. its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule: Version III. St. Louis: Washington University School of Medicine. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins L. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule: Version III revised (DIS-III-R) Washington University School of Medicine; St. Louis: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cumming G. Inference by eye: Reading the overlap of independent confidence intervals. Stat Med. 2009;28(2):205–220. doi: 10.1002/sim.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland M. An introduction to medical statistics. Oxford Medical Publications; Oxford, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Wang PS. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the united states. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:115–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: Results of the netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33(12):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streiner DL, Patten SB, Anthony JC, Cairney J. Has 'lifetime prevalence' reached the end of its life? an examination of the concept. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18(4):221–228. doi: 10.1002/mpr.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: A review of population studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(3):163–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.