Abstract

The generation of reactive nitrogen/oxygen species (RN/OS) represents an important mechanism in erythropoietin (EPO) expression and skeletal muscle adaptation to physical and metabolic stress. RN/OS generation can be modulated by intense exercise and nutrition supplements such as α-lipoic acid, which demonstrates both anti- and pro-oxidative action. The study was designed to show the changes in the haematological response through the combination of α-lipoic acid intake with running eccentric exercise. Sixteen healthy young males participated in the randomised and placebo-controlled study. The exercise trial involved a 90-min run followed by a 15-min eccentric phase at 65% VO2max (-10% gradient). It significantly increased serum concentrations of nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and pro-oxidative products such as 8-isoprostanes (8-iso), lipid peroxides (LPO) and protein carbonyls (PC). α-Lipoic acid intake (Thiogamma: 1200 mg daily for 10 days prior to exercise) resulted in a 2-fold elevation of serum H2O2 concentration before exercise, but it prevented the generation of NO, 8-iso, LPO and PC at 20 min, 24 h, and 48 h after exercise. α-Lipoic acid also elevated serum EPO level, which highly correlated with NO/H2O2 ratio (r = 0.718, P < 0.01). Serum total creatine kinase (CK) activity, as a marker of muscle damage, reached a peak at 24 h after exercise (placebo 732 ± 207 IU · L-1, α-lipoic acid 481 ± 103 IU · L-1), and correlated with EPO (r = 0.478, P < 0.01) in the α-lipoic acid group. In conclusion, the intake of high α-lipoic acid modulates RN/OS generation, enhances EPO release and reduces muscle damage after running eccentric exercise.

Keywords: nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, muscle damage, protein carbonylation, lipid peroxidation

INTRODUCTION

Intense exercise involving eccentric contractions induces skeletal muscle damage including reactive nitrogen/oxygen species (RN/OS) generation, which represents an important mechanism in the adaptation to physical work. Nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as cellular mediators in signal transmission, can activate transcription factors e.g. hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) [6, 10, 17, 22]. HIF-1 is an essential binding element in the 3’ enhancer of the EPO gene, and its activity can be regulated by several different mechanisms including oxygen-dependent pathways and oxygen-independent factors such as sirtuins, protein kinases, microRNAs and RN/OS. The mechanism by which RN/OS acts on HIF-1 and EPO-gene expression is controversially discussed. Fandrey et al. [10] demonstrated that the low endogenous H2O2 production under hypoxic conditions is associated with a high rate of EPO synthesis. In contrast, Chandel et al. [8] reported an increase in H2O2 generation and HIF-1 activity under hypoxic conditions.

Hypoxia is a major regulatory factor for EPO synthesis. However, several chemically diverse antioxidants also can affect HIF-1 activity and EPO expression [11, 15, 18, 27, 31, 37, 38]. α-Lipoic acid is a very interesting antioxidant because of its anti- and pro-oxidative activity. It reduces superoxide and hydroxyl radicals but it can generate H2O2 via auto-oxidation depending on the time and dose of its administration [26]. In animal studies, it has been shown that α-lipoic acid at doses from 12.5 mg · kg-1 to 100 mg · kg-1 body weight improved the anti-oxidative response while doses over 100 g · kg-1 induced pro-oxidative processes [7, 14]. In human studies, α-lipoic acid is used as a dietary supplement at doses from 100 to 1200 mg daily but as a medication it is recommended at high doses (up to 1800 mg · d-1) for a long period (up to 6 months) in diabetic neuropathy and other diseases [2, 26]. The time and dose of α-lipoic acid supplementation seems to be important for α-lipoic acid activity. In our previous study, 600 mg of α-lipoic acid revealed an antioxidant action but did not improve the haematological response [36]. Freudenthaler et al. [11] used very short-term α-lipoic acid treatment (1200 mg) with an infusion pump (20 mg · min-1) during 6 h hypoxia. They did not observe any changes in markers of RN/OS activity or EPO level. Nonetheless, a recent study provided evidence for the use of α-lipoic acid as an EPO adjuvant, reducing the requirement for EPO in patients undergoing haemodialysis [9].

This study was designed to determine whether intake of high-dose α-lipoic acid before running eccentric exercise demonstrates antioxidative activity and enhances EPO release through changes in RN/OS generation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixteen healthy males participated in this randomised and placebo-controlled study (Table 1). During the study, subjects were requested to avoid nutritional supplements and physical effort for 48 h before and after the exercise trials. All the subjects were informed of the aim of the study and gave their written consent for participation in the project. The protocol of the study was approved by the local ethics committee in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

TABLE 1.

ANTHROPOMETRIC AND BODY COMPOSITION DATA IN SUBJECTS (MEAN ± SD)

| α-Lipoic acid n = 8 | Placebo n = 8 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 20.5 ± 0.1 | 20.9 ± 0.8 | 0.414 |

| Height (cm) | 183.1 ± 4.1 | 175.6 ± 7.1 | 0.072 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.1 ± 4.0 | 72.5 ± 7.7 | 0.677 |

| BMI (kg·m-2) | 22.2 ± 1.0 | 23.3 ± 1.2 | 0.139 |

| FM (kg) | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 14.8 ± 3.5 | 0.235 |

| FM (%) | 17.5 ± 2.0 | 20.1 ± 3.4 | 0.105 |

| FFM (kg) | 61.1 ± 3.5 | 58.2 ± 5.4 | 0.343 |

| FFM (%) | 82.5 ± 2.0 | 79.9 ± 3.4 | 0.105 |

Note: BMI – body mass index; FFM – fat-free mass; FM – fat mass

The maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) was determined on a treadmill Trackmaster TM310 (USA) at the temperature of 22°C and the relative air humidity of 60%. Breath-by-breath oxygen uptake was continuously recorded using the Oxycon Mobile ergospirometric system (Viasys Healthcare Inc., USA). Heart rate was continuously recorded during the test using a portable heart rate telemetry device: Polar Sport Tester T61 (Finland). The test was incremental and progressive; all subjects commenced at a 4.5 mph running speed and it was increased by 0.5 mph every 2 min until the maximal level of recorded parameters was achieved. The VO2max was determined between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m. a week before the beginning of the experiment.

The subjects were assigned to one of two groups: placebo and α-lipoic acid (Thiogamma 600 Wörwag Pharma; 2 × 600 mg · d-1 for 10 days prior to the exercise trial). The exercise trial involved a 90 min run at 65% VO2max (0% gradient) followed by a 15-min eccentric phase (-10% gradient) at 65% VO2max. Blood samples were obtained from the antecubital vein using S-Monovette tubes (Sarstedt, Austria) at pre-exercise and post-exercise periods (20 min, 24 h and 48 h). Within 20 min, blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 g and 4°C for 10 min. Serum for markers of RN/OS activity, EPO and CK was stored at -80°C.

Reactive nitrogen/oxygen species (RN/OS)

Serum nitric oxide (NO) and hydroperoxide (H2O2) concentrations were determined using Oxis Research kit (USA). NO and H2O2 were measured immediately after serum collection, on the day of exercise study. NO and H2O2 detection limits were 0.5 nmol · mL-1 and 6.25 nmol · mL-1, respectively. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) for the NO kit and the H2O2 kit was <10%.

Markers of RN/OS activity

Serum 8-isoprostanes (8-iso) were measured with a Cayman kit (USA). The 8-Iso detection limit for the procedure was 2.7 pg · mL-1, and the intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 6.4%. Lipid peroxide (LPO) and protein carbonyl (PC) concentrations were determined using the Oxis Research kit (USA) and Alexis Biochemicals kit (USA). The detection limits for LPO and PC were 0.1 nmol · mL-1. The intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for LPO and PC kits were <10%.

Erythropoietin

Serum erythropoietin (EPO) level was determined by the enzyme immunoassay method using a commercial kit from R&D Systems (USA). The EPO detection limit for the applied kit was 0.6 mIU · mL-1. The intra-assay CV for the EPO kit was <8%.

Haematological variables

Haemoglobin (HB), haematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) as well as erythrocyte (RBC) and reticulocyte counts (RET) and reticulocyte relative number (percentage) (RET%) were assessed using Sysmex XE-2100 (Japan) in EDTA blood samples.

Creatine kinase

Total serum creatine kinase (CK) activity was used as a marker of muscle damage and was evaluated using an Emapol kit (Poland). The CK detection limit for the applied kit was 6 IU · L-1. The intra-assay CV for the CK kit was 1.85%.

Statistical analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used to determine the effect of exercise and α-lipoic acid on analysed parameters [(pre-exercise vs. post-exercise) × (placebo vs. α-lipoic acid)]. Tukey's post-hoc test was used to determine differences between group means. The relationships between variables were determined using Pearson's correlation and linear regression. All results are expressed as mean and standard deviation (x ± SD). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica 10 and the statistical package R2.10.0 (R Development Core Team 2009).

RESULTS

Reactive nitrogen/oxygen species

The running eccentric exercise caused a significant increase in NO and H2O2 concentrations. Changes in H2O2 already occurred at 20 min after exercise and were higher than changes in NO generation. The H2O2 level was still elevated (P<0.001) at 48 h after exercise. ANOVA showed a significant interaction between α-lipoic acid and exercise. α-Lipoic acid intake increased H2O2 concentration 2-fold at pre-exercise but reduced changes in H2O2 and NO during recovery. Changes in NO/H2O2 ratio were mainly dependent on H2O2 level. α-Lipoic acid reduced the NO/H2O2 ratio 2-fold at pre-exercise, 20 min and 24 h, but elevated it at 48 h after exercise (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

SELECTED NITRO-OXIDATIVE STRESS MARKERS IN α-LIPOIC ACID (N = 8) AND PLACEBO (N = 8) GROUPS (MEAN ± SD)

| Pre-exercise (after 10-d placebo or α-lipoic acid intake) | Post-exercise 20 min | Post-exercise 24 h | Post-exercise 48 h | P-value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO nmol·mL-1 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 26.64 ± 4.96 | 31.67 ± 7.35 | 34.37 ± 8.77 | 30.33 ± 7.56 | 0.215 |

| Placebo | 32.99 ± 4.76 | 35.08 ± 5.45 | 45.65 ± 5.58 | 35.88 ± 4.91 | <0.001 |

| H2O2nmol·mL-1 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 25.01 ± 2.21 | 22.05 ± 4.97 | 25.73 ± 2.72 | 17.04 ± 1.84 | <0.001 |

| Placebo | 13.71 ± 3.39 | 30.26 ± 4.37 | 20.99 ± 3.42 | 26.28 ± 2.61 | <0.001 |

| NO/H2O2 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 1.07 ± 0.24 | 1.52 ± 0.55 | 1.35 ± 0.36 | 1.80 ± 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Placebo | 2.57 ± 0.87 | 1.19 ± 0.28 | 2.24 ± 0.55 | 1.38 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| 8-iso pg·mL-1 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 18.43 ± 3.90 | 31.92 ± 8.31 | 17.83 ± 5.83 | 16.67 ± 3.85 | 0.479 |

| Placebo | 24.38 ± 8.40 | 40.92 ± 6.32 | 22.00 ± 6.68 | 27.68 ± 8.29 | <0.001 |

| LPO nmol·mg-1 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 1.75 ± 0.56 | 2.22 ± 0.38 | 2.04 ± 0.61 | 1.77 ± 0.57 | 0.275 |

| Placebo | 1.37 ± 0.42 | 2.50 ± 0.58 | 2.16 ± 0.71 | 1.55 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| PC nmol·mg-1 | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 5.20 ± 0.95 | 6.66 ± 1.33 | 6.65 ± 1.54 | 6.87 ± 1.05 | <0.05 |

| Placebo | 4.60 ± 0.77 | 6.78 ± 1.43 | 7.40 ± 1.88 | 5.67 ± 1.62 | <0.05 |

Note: The first P-value for each variable is the group x time interaction effect, and the second is the time effect.

Abbreviations: NO nitric oxide, H2O2 hydrogen peroxide, 8-isoprostanes, LPO lipid peroxides, PC protein carbonyls

Markers of RN/OS activity

The running eccentric exercise significantly elevated 8-iso, LPO and PC concentrations at 20 min and 24 h after exercise. α-Lipoic acid prevented post-exercise changes in 8-iso, LPO and PC levels; thus it revealed antioxidative activity. However, there were no significant differences in LPO and PC between placebo and α-lipoic acid (Table 2).

Erythropoietin

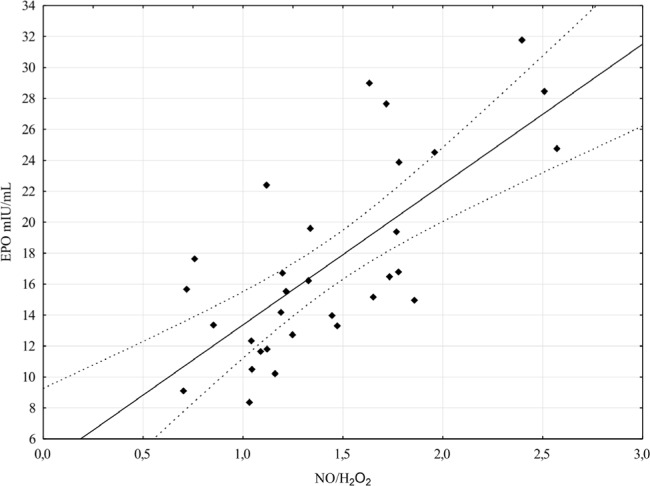

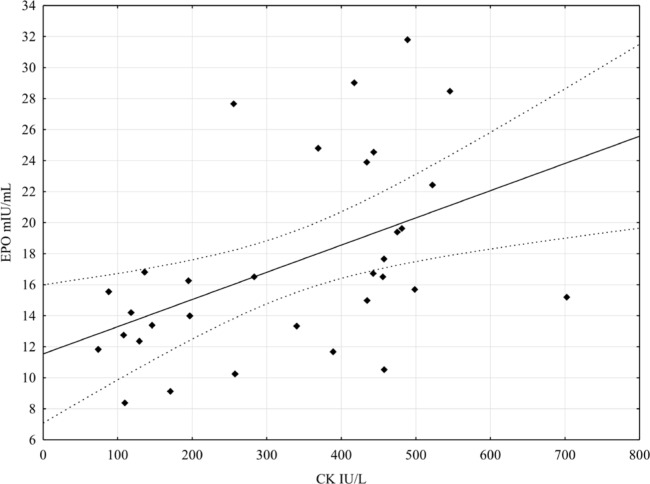

The exercise trial significantly increased EPO concentration at 20 min post-exercise. α-Lipoic acid enhanced EPO production both before exercise and during recovery. EPO level was especially high at 48 h after exercise. Interestingly, EPO did not correlate with NO and H2O2 separately but correlated with NO/H2O2 ratio in the α-lipoic acid group (Figure 1). EPO also correlated with total CK activity (r = 0.478, P<0.01), which reached a peak at 24 h after exercise (Figure 2). This means that changes in RN/OS generation and muscle damage are important factors affecting EPO release.

FIG. 1.

THE RELATION OF ERYTHROPOIETIN (EPO) LEVEL WITH NITRIC OXIDE AND HYDROGEN PEROXIDE RATIO (NO/H2O2) FOLLOWING EXERCISE TRIAL IN α-LIPOIC ACID GROUP (N = 8)

Note: r = 0.718, P<0.01

FIG. 2.

THE RELATION OF ERYTHROPOIETIN (EPO) LEVEL TO TOTAL CREATINE KINASE (CK) ACTIVITY FOLLOWING EXERCISE TRIAL IN α-LIPOIC ACID GROUP (N = 8)

Note: r = 0.478, P < 0.01.

Haematological variables

HB concentration did not change following exercise but it was significantly elevated after α-lipoic acid at pre-exercise, 20 min, and 24 h post-exercise. Other haematological variables did not change after either exercise and α-lipoic acid; however, RBC and RET numbers as well as MCV tended to high values after α-lipoic acid intake (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

ERYTHROPOIETIN AND HAEMATOLOGICAL VARIABLES IN α-LIPOIC ACID (N = 8) AND PLACEBO (N = 8) GROUPS (MEAN ± SD)

| Pre-exercise (after 10-d placebo or α-lipoic acid intake) | Post-exercise 20 min | Post-exercise 24 h | Post-exercise 48 h | P-value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPO (mIU·mL-1) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 12.36 ± 2.50 | 16.51 ± 5.52 | 19.63 ± 10.25 | 23.90 ± 11.24 | 0.154 |

| placebo | 7.22 ± 1.31 | 13.41 ± 4.89 | 10.95 ± 4.85 | 10.71 ± 5.16 | <0.01 |

| HB (g·dL-1) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 16.00 ± 0.45 | 16.09 ± 0.45 | 15.64 ± 0.82 | 15.23 ± 0.71 | 0.457 |

| placebo | 14.60 ± 0.53 | 15.26 ± 0.77 | 14.50 ± 0.84 | 14.59 ± 0.67 | <0.05 |

| RBC (mln·mm-3) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 5.42 ± 0.26 | 5.44 ± 0.22 | 5.32 ± 0.13 | 5.17 ± 0.16 | 0.708 |

| placebo | 5.17 ± 0.18 | 5.14 ± 0.20 | 5.01 ± 0.26 | 5.03 ± 0.27 | >0.05 |

| HCT (%) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 47.70 ± 1.12 | 47.38 ± 1.23 | 47.10 ± 1.47 | 45.74 ± 1.76 | 0.627 |

| placebo | 45.00 ± 1.49 | 44.69 ± 1.91 | 43.46 ± 1.94 | 43.69 ± 1.66 | <0.05 |

| RET (%) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 7.75 ± 1.39 | 7.63 ± 1.49 | 7.88 ± 1.36 | 6.38 ± 1.22 | 0.081 |

| placebo | 5.38 ± 0.86 | 4.88 ± 0.93 | 4.88 ± 0.78 | 5.50 ± 1.00 | >0.05 |

| MCV (fL) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 89.13 ± 2.21 | 88.69 ± 2.23 | 88.99 ± 2.37 | 89.53 ± 1.81 | 0.998 |

| placebo | 86.29 ± 2.41 | 85.84 ± 2.41 | 85.89 ± 2.27 | 86.53 ± 2.07 | >0.05 |

| MCH (pg·RBC-1) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 29.87 ± 1.35 | 29.97 ± 1.45 | 29.84 ± 1.33 | 29.87 ± 1.36 | 0.999 |

| placebo | 28.98 ± 0.89 | 29.16 ± 0.90 | 29.05 ± 0.94 | 29.04 ± 0.78 | >0.05 |

| MCHC (g·dL-1) | |||||

| α-lipoic acid | 33.18 ± 0.89 | 33.50 ± 1.00 | 33.29 ± 0.93 | 33.18 ± 0.94 | 0.997 |

| placebo | 33.36 ± 0.36 | 33.73 ± 0.23 | 33.39 ± 0.53 | 33.36 ± 0.52 | >0.05 |

Note: The first P-value for each variable is the group x time interaction effect, and the second is the time effect.

Abbreviations: EPO – erythropoietin, HB – haemoglobin, RBC – red blood cells, HCT – haematocrit, RET – reticulocytes, MCV – mean cell volume, MCH – mean corpuscular haemoglobin, MCHC – mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration

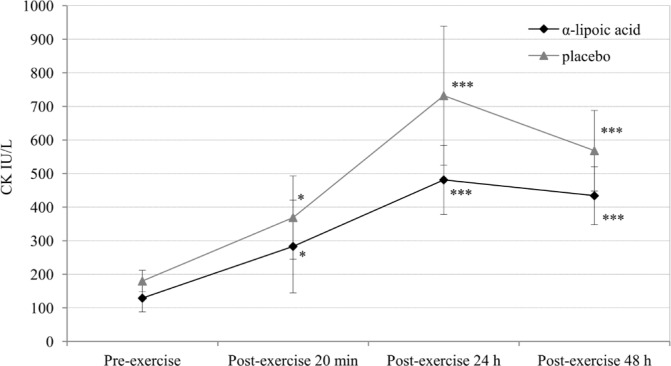

Creatine kinase

Total initial CK activity was slightly lower in the α-lipoic acid group than in placebo but the difference was not statistically significant. Interestingly, in the group treated with α-lipoic acid, CK activity was significantly lower than in placebo during recovery. The CK peak values were reached at 24 h after the cessation of exercise in both groups (481 ± 103 IU · L-1 vs. 732 ± 207 IU · L-1) and then gradually fell until 48 h post-exercise (434 ± 86 IU · L-1 vs. 568 ± 120 IU · L-1) (Figure 3).

FIG. 3.

CHANGES IN TOTAL SERUM CREATINE KINASE (CK)

Note: *P < 0.05, *P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 significantly different compared with pre-exercise level. CK activity was significantly different (P < 0.05) in α-lipoic acid compared with placebo at 24 h post-exercise.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have concluded that intracellular RN/OS production is a required signal for the exercise adaptation that occurs in the cardiovascular system and skeletal muscles in response to repeated exercise [29]. Our results have shown that running eccentric exercise elevates NO and H2O2 generation. However, a rise in H2O2 occurred before changes in NO level. Lima-Cabello et al. [22] demonstrated that muscle contractions modulate the NO synthesis via NO synthases (NOS) through the signalling pathways are controlled by H2O2-activated nuclear factor κB. Therefore antioxidants affecting H2O2 generation can indirectly modulate NO release.

The applied high α-lipoic acid dose increased H2O2 but reduced NO concentration. This could be caused by inhibition of an inducible isoform of NOS expression by α-lipoic acid through destabilization of its mRNA, resulting in decreased NO production [35]. The excess NO reacts with the superoxide anion to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO-), which can induce mitochondrial dysfunction, lipid and protein oxidation [28]. α-Lipoic acid shows the ability to react directly with ONOO- and to reduce nitro-oxidative stress [33]. It has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing various diseases in which RN/OS have been implicated, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension and radiation injury [30].

The measure of RN/OS markers such as 8-iso, LPO and PC can offer an empirical view on the complex process of peroxidation and carbonylation followed by diseases, aging or exhaustive exercise [29]. Our study confirmed the effectiveness of α-lipoic acid in the protection of lipids and proteins against over-activity of RN/OS. The used markers of RN/OS activity decreased following high α-lipoic acid intake, especially lipid peroxidation products 8-iso and LPO. Previously, a few researchers reported a positive effect of α-lipoic acid on lipid composition in various tissues. Manda et al. [23] observed a significant decrease in peroxidation products in X-irradiated mouse cerebellar tissue following treatment with α-lipoic acid. Baydas et al. [1] demonstrated an α-lipoic acid-mediated protective effect against lipid peroxidation in the glial cells of diabetic rats.

NO and H2O2 are involved in signal transduction pathways. H2O2 was previously indicated as part of the O2-sensing mechanism stabilizing transcription factor HIF-1 and regulating EPO expression, and as a signal for cell growth and differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells [17]. The next observations indicated the key role of NO in HIF-1α stabilization [6]. According to Haase [13], during hypoxia transcriptional activity of HIF-1 is more dependent on changes in H2O2, whereas during non-hypoxic conditions HIF-1 activity is related to NO, pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-β and TNFα, as well as growth factors including epidermal growth factor, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor I. We observed that α-lipoic acid elevates H2O2 and EPO, and reduces NO level at rest. This means that H2O2 may be more involved in EPO release than NO. Although EPO did not separately correlate with H2O2 and NO, it highly correlated with the ratio of NO to H2O2. We suppose that EPO synthesis may require changes in levels of both molecules. It was recently reported that HIF-1 transcriptional activity and EPO expression are achieved through two parallel pathways: a decrease in O2-dependent hydroxylation of HIF-1 and S-nitrosylation of HIF-1 pathway components [16].

α-Lipoic acid can effect muscle regeneration through regulation of RN/OS and EPO production. Endogenously produced EPO and/or expression of the EPO receptor gives rise to autocrine and paracrine signalling in skeletal muscles particularly during hypoxia and injury conditions. In the last decade, numerous studies have confirmed that apart from its haematopoietic effect, EPO is active in muscle, neural, endothelial, cardiovascular and renal tissues [21, 25]. In skeletal muscles, EPO stimulates proliferation of myoblasts and has a potential role in muscle mass maintenance. Furthermore, EPO directly contributes to increased PGC-1α activity and affects skeletal muscle development and the balance of slow and fast-twitch fibre determination [34]. High α-lipoic acid intake increased EPO concentration and reduced total CK activity at 24 h and 48 h after exercise. A significant positive correlation was observed between CK and EPO. Mille-Hamard et al. [25] reported that EPO exerts both direct and indirect muscle-protecting effects during intense exercise. However, the authors stressed that the signalling pathway involved in protective effects of EPO remains to be described in detail.

The increase in serum CK activity is normally related to intense physical activity and strongly correlates with the type and the amount of exercise. It depends on the degree of injury of the skeletal muscle cell structure. Therefore, CK is widely used in monitoring of training load, physical efficacy and overtraining in athletes. The skeletal muscles performing eccentric exercise are particularly exposed to damage as the result of disruption of sarcomeres, leading to intensified CK efflux into the extracellular space and markedly higher CK activity in the blood [24]. The study revealed differences in CK response to eccentric exercise depending on α-lipoic acid intake. Participants supplemented with α-lipoic acid had significantly lower CK activity than control individuals taking placebo. This was in line with earlier observations of Kim and Chae [20], who demonstrated significantly lower CK values in rats supplemented with α-lipoic acid for 6 weeks irrespectively of exercise. One of the postulated reasons of lower muscle injury could be membrane protective effects of α-lipoic acid against exercise-induced oxidative damage as the result of attenuation of lipid peroxidation and membrane permeability [12]. Although the CK activity shows remarkable intra- and inter-individual variations under exercise condition, some authors have defined a blurred boundary between harmless and damaging physical activities at the level of about 300-500 IU · mL-1 of the enzyme activity [3]. α-Lipoic acid intake significantly reduced excessive CK efflux during exercise performance thus suggesting its muscle protective capabilities in the study. This highly beneficial effect could be a matter of particular interest for the future in preventing an extremely high CK response to exercise rhabdomyolysis in athletes [4, 19] and statin-induced rhabdomyolysis in a substantial proportion of patients treated for dyslipidaemia [5, 32].

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the current results confirm the antioxidative properties of α-lipoic acid, and indicate a possible use of α-lipoic acid to improve EPO production and skeletal muscle regeneration through changes in the RN/OS ratio at rest and after exercise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant NN404 155534 from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, and from the University School of Physical Education Poznan, Poland.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baydas G, Donder E, Kiliboz M, Sonkaya E, Tuzcu M, Yasar A, Nedzvetskii VS. Neuroprotection by α-lipoic acid in streptozocin-induced diabetes. Biochemistry. 2004;69:1001–1005. doi: 10.1023/b:biry.0000043542.39691.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilska A, Dudek M, Iciek M, Kwiecien I, Jezewicz-Sokolowska M, Filipek B, Wlodek L. Biological actions of lipoic acid associated with sulfane sulfur metabolism. Pharmacol. Reports. 2008;60:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brancaccio P, Maffulli N, Limongelli F.M. Creatine kinase monitoring in sport medicine. Br. Med. Bull. 2007;81-82:209–230. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brancaccio P, Maffulli N, Politano L, Lippi G, Limongelli F.M. Perisitent hyperCKemia in athletes. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons J. 2001;1:31–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewster L.M, Mairuhu G, Sturk A, van Montfrans G.A. Distribution of creatine kinase in the general population: implications for statin therapy. Am. Heart J. 2007;154:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brüne B, Zhou J. The role of nitric oxide (NO) in stability regulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:845–855. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cakatay U. Pro-antioxidant activities of α-lipoic acid and dihydrolipoic acid. Medical Hypotheses. 2006;66:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandel N.S, McClintock D.S, Feliciano C.E, Wood T.M, Melendez J.A, Rodriguez A.M, Schumacker P.T. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Nakib G.A, Mostafa T.M, Abbas T.M, El-Shishtawy M.M, Mabrouk M.M, Sobh M.A. Role of alpha-lipoic acid in the management of anemia in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2013;6:161–168. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S49066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fandrey J, Frede S, Jelkmann W. Role of hydrogen peroxide in hypoxia-induced erythropoietin production. Biochem. J. 1994;303:507–510. doi: 10.1042/bj3030507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freudenthaler S.M, Schreeb K.H, Wiese A, Pilz J, Gleiter C.H. Influence of controlled hypoxia and radical scavenging agents on erythropoietin and malondialdehyde concentrations in humans. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2002;174:231–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2002.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorąca A, Huk-Kolega H, Piechota A, Kleniewska P, Ciejka E, Skibska B. Lipoic acid – biological activity and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Rep. 2011;63:849–858. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factors in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2006;291:F271–F281. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00071.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han P, Yin J, He P, Ma Xi. Dose-effect study of lipoic acid supplementation on growth performance in a weaned rat model. J. Anim. Sci. Biotech. 2011;2:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildebrandt W, Alexander S, Bärtsch P, Dröge W. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on the hypoxic ventilatory response and erythropoietin production: linkage between plasma thiol redox state and O2 chemosensitivy. Blood. 2002;99:1552–1555. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho J.J.D, Man H.S.J, Marsden P.A. Nitric oxide signalling in hypoxia. J. Mol. Med. 2012;90:217–231. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang L.E, Arany Z, Livingston D.M, Bunn H.F. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor depends primarily upon redox-sensitive stabilization of its alpha subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:32253–32259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jelkmann W, Pagel H, Hellwig T, Fandrey J. Effects of antioxidant vitamins on renal and hepatic erythropoietin production. Kidney Int. 1997;51:497–501. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenney K, Landau M.E, Gonzales R.S, Hundertmark J, O'Brien K, Campbell W.W. Serum creatine kinase after exercise: drawing the line between physiological response and exertional rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:356–362. doi: 10.1002/mus.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim H.T, Chae C.H. Effect of exercise and α-lipoic acid supplementation on oxidative stress in rats. Biol. Sport. 2006;23:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamon S, Russell A.P. The role and regulation of erythropoietin (EPO) and its receptor in skeletal muscle: how much do we really know? Front Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima-Cabello E, Cueavas M.J, Garatachea N, González-Gallego J. Eccentric exercise induces nitric oxide synthase expression through nuclear factor-κB modulation in rat skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;108:575–583. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00816.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manda K, Ueno M, Moritake T, Anzai K. Radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction and cerebellar oxidative stress in mice: protective effect of alpha-lipoic acid. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;177:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKune A.J, Semple S.J, Peters-Futre E.M. Acute exercise-induced muscle injury. Biol. Sport. 2012;29:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mille-Hamard L, Billat V.L, Henry E, Bonnamy B, Joly F, Benech P, Barrey E. Skeletal muscle alterations and exercise performance decrease in erythropoietin-deficient mice: a comparative study. BMC Med. Genomics. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moini H, Packer L, Saris N.E.L. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant of α-lipoic acid and dihydrolipoic acid. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002;182:84–90. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niess A.M, Fehrenbach E, Lorenz I, Müller A, Northoff H, Dickhuth H.H. Antioxidant intervention does not affect the response of plasma erythropoietin to short-term normobaric hypoxia in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;96:1231–1235. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00803.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacher L, Beckman J.S, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers S.K, Jackson M.J. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1243–1276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochette L, Ghibu S, Richard C, Zeller M, Cottin Y, Vergely C. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of α-lipoic acid and therapeutic potential. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013;57:114–125. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sentürk U.K, Yalcin O, Gunduz F, Kuru O, Meiselman H.J, Baskurt O.K. Effect of antioxidant vitamin treatment on the time course of haematological and hemorheological alterations after an exhausting exercise episode in human subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;98:1272–1279. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00875.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomaszewski M, Stępień K.M, Tomaszewska J, Czuczwar S.J. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:859–866. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trujillo M, Radi R. Peroxynitrite reaction with the reduced and the oxidized forms of lipoic acid: new insights into the reaction of peroxynitrite with thiols. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;397:91–98. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Jia Y, Rogers H, Suzuki N, Gassmann M, Wang Q, McPherron A.C, Kopp J.B, Yamamoto M, Noguchi C.T. Erythropoietin contributes to slow oxidative muscle fiber specification via PGC-1α and AMPK activation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013;45:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada M, Kaibori M, Tanaka H, Habara K, Hijikawa T, Tanaka Y, Oishi M, Okumura T, Nishizawa M, Kwon A.H. α-Lipoic acid prevents the induction of iNOS gene expression through destabilization of its mRNA in pro-inflammatory cytokine-stimulated hepatocytes. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012;57:943–95. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-2012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zembron-Lacny A, Slowinska-Lisowska M, Szygula Z, Witkowski K, Szyszka K. The comparison of antioxidant and hematological properties of N-acetylcysteine and alpha-lipoic acid in physically active males. Physiol. Res. 2009;58:855–861. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zembron-Lacny A, Slowinska-Lisowska M, Szygula Z, Witkowski Z, Szyszka K. Modulatory effect of N-acetylcysteine on pro-antioxidant status and haematological response in healthy men. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2010;66:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s13105-010-0002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z.G, Xu P, Liu Q, Yu C.H, Zhang Y, Chen S.H. Effect of tea polyphenols on cytokine gene expression in rats with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2006;6:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]