Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the rear knee angle range in the set position that allows sprinters to reach greater propulsion on the rear block during the sprint start. Eleven university-track team sprinters performed the sprint start using three rear knee angle conditions: 90°, 115° and 135°. A motion capture system consisting of 8 digital cameras (250 Hz) was used to record kinematic parameters at the starting block phase and the acceleration phase. The following variables were considered: horizontal velocity of the centre of mass (COM), COM height, block time, pushing time on the rear block, percentage of pushing time on the rear block, force impulse, push-off angle and length of the first two strides. The main results show that first, horizontal block velocity is significantly greater at 90° vs 115° and 135° rear knee angle (p<0.05 and p<0.001 respectively) at block clearance and the first two strides; second, during the pushing phase, the percentage of pushing time of the rear leg is significantly greater at 90° vs 135° rear knee angle (p<0.01). No significant difference was found for block time among the conditions. These results indicate that block velocity is the main kinematic parameter affected by rear knee angle during the starting block phase and acceleration phase. Furthermore, the 90° rear knee angle allows for a better push-off of the rear leg than larger angles at the set position. The findings of this study provide some direction and useful practical advice in defining an efficient rear leg biomechanical configuration at the set position.

Keywords: block velocity, motion analysis, set position, sprint technique

INTRODUCTION

In the sprint and hurdles track-and-field races, the sprint start is a crucial skill for a sprinter to maximize performance over race distance. The sprint start is a complex skill characterized by a multi-joint and multi-plane task requiring stretch-shorten cycle type motion and complex muscle coordination in order to reach a large force exerted in the horizontal direction in a short time [13].

Efficient acceleration over the first portion of a race is influenced by the way a sprinter is positioned in the blocks at the set command and the mechanics of leaving the blocks at the sound of the gun [29]. The kinematic and kinetic patterns of elite athletes during the starting block phase and acceleration phase have received considerable attention and many variables have been studied to explain the phenomenon of the sprint start [1, 3, 5–7, 19–22, 27, 28]. The results of these studies indicate that an essential component of the starting technique is the geometry of the body configuration at the set command [2], described in terms of block positioning [14, 23, 27], centre of gravity position and body angles [14, 24, 27]. In particular, “optimal” joint angles of the front and rear leg at the set position are a critical determinant of body configuration, in order to reach a greater horizontal impulse and a high horizontal velocity component [4, 24]. Even if the front leg is the greater contributor to total impulse due largely to its greater contact time during the block phase, the importance of rear leg action has also been reported [1, 10, 24, 30].

The rear knee angle has been shown to range widely in elite sprinters: 91°-102° [2], 115°-138° [4], 90°-154° [1], 118°- 136° [21, 22, 24], 100°-126° [6], 115°-130° [14]. The spread range of rear knee angle values reported in these studies is based on the observed starting block technique used by elite sprinters and may reflect individual preferences; in addition, a rationale for an objective recommended rear knee angle for sprinters at the set position has not been reported yet. It has been shown that elite sprinters are characterized by higher propulsion on the rear block during starting compared with well-trained sprinters [11], as well as similar front and rear peak force at the block during the starting phase [12, 14, 24, 26, 30]. Mero et al. [24] suggested that the between-sprinters differences in set position joint angle might be due to strength differences, with stronger sprinters able to adopt more acute joint angles and extend the joint over a greater range.

As regards the influence of knee joint position on kinetic and electromyographic properties, it has been widely investigated for more than twenty years. A few studies of isometric and isokinetic strength characteristics indicated that knee extension strength is greatest at 115°-120° of flexion [17, 25]. However, strength tests are often single-joint, single-plane, or open kinetic chain tasks, thereby not symbolizing a multi-joint and multi-plane movement-specific contest (e.g. sprint start) to predict the performance during more complex movements.

As the pattern of the rear leg at the set position is a critical determinant of body configuration, it would be worthwhile to elucidate the effect of different rear knee joint angle degrees during the sprint start performance. In other words, it would be interesting to understand which geometric rear leg configuration allows sprinters to achieve greater propulsion on the rear block during a sprint start, in order to improve their performance over sprint races. Despite the existence of a large body of information regarding the set position, to the authors’ knowledge no experimental study has tried to examine whether changing the angle at the rear knee joint at the set position influences kinematic parameters in sprinters. Therefore, the purpose of this work was to investigate the rear knee angle associated with a greater impulse and a higher horizontal velocity in the starting block phase and acceleration phase. Specifically, this study compared the major kinematic parameters of eleven university-track team sprinters performing sprint starts at three different knee angle conditions in the rear leg at the set position.

Three different rear knee angle conditions (90°, 115° and 135°) were selected for the experiment. These reflect three peculiar values adopted by elite sprinters and the optimal range proposed by isometric and isokinetic strength studies for knee extension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eleven university-track team sprinters (five females and six males) studying at the School of Exercise and Sport Sciences took part in this study. Female and male subjects’ mean age, height and weight (± SD) were 21.4 ± 2.3 and 21.5 ± 1.8 years, 171 ± 3.2 and 175 ± 6.5 cm, and 61.8 ± 3.2 and 64.8 ± 6.1 kg, respectively. Their mean 100 m personal best was 12.0 ± 0.1 s for men and 13.1 ± 0.9 s for women. All measurements were taken in the outdoor season (April-May). The participants had no previous history of osteo-articular traumas or neuropathies in the lower limbs. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in this study, and the protocol was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Verona Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

The kinematic measurements were carried out in the biomechanics laboratory. A professional starting block (Polanik, Poland) was placed against the wall of the laboratory on the rubberized surface. An opto-eletronic motion capture system (MX Ultranet, VICON, Oxford, UK) consisting of eight cameras (MX-13, VICON, Oxford, UK) was used to record the 3D marker trajectories. Cameras were placed on tripods around the volume of movement at a height that permitted optimal detection of the entire movement. The sampling frequency of the system was 250 Hz. Twenty-two retro-reflective passive markers (14 mm in diameter) were placed bilaterally, with bi-adhesive tape, on the following body landmarks: temple, acromion process of the scapula, olecranon process of the ulna, styloid process of the ulna, anterior superior iliac spine, greater trochanter of the femur, lateral epicondyle of the femur, lateral malleolus, calcaneus, and the first and fifth metatarsal head. Dedicated software (Workstation 5.2, VICON, Oxford, UK) was used for digitization and reconstruction of the markers’ positions. The estimation of the total body centre-of-mass (COM) position in the sagittal plane was obtained by a kinematic model of the body: the anatomical structure was assumed to be bilateral with seven rigid anthropometric segments for each body side (foot, shank, thigh, trunk, upper arm, forearm and head) identified in the space by means of motion analysis systems [31]. Inertial parameters of the body segments derived from an anthropometric model based on Dempster's estimates of the segment weight and segment mass-centre location [9].

Sprint Start Testing Protocol

The desired outcome of the starting action was to impart as large a horizontal velocity as possible to the body upon clearing the starting blocks yet also to achieve body positioning conducive to further acceleration.

The rear knee joint angle was determined through the use of three standard goniometers fixed at 90°, 115° and 135° and the position of other body segments occurred respectively to the assumed rear knee angle across the three conditions. Participants were allowed to use their own preferred block spacing (horizontal distance between the front block and the start line, and between the front and rear blocks), and wore their own training shoes.

Following a standardized warm-up, including 10 minutes of light aerobic exercise, dynamic stretching, and familiarization with the sprint protocol, sprint assessment began. Each trial was initiated with the “on your marks” and “set position” commands provided by a qualified starter. After “the gun”, the participants left the starting block and ran as fast as possible for at least 5 m. Ten valid trials were collected for each of the three knee flexion-extension angles of the rear leg (90°, 115° and 135° [total: 30 trials/ participant]) to ensure adequate performance measurement. The whole procedure was carried out in one session and the order of test angles was randomized to prevent any testing effect. The participants were allowed to rest for at least two minutes between trials and ten minutes after ten trials; fatigue was never an issue due to the resting time available throughout the session.

Data analysis

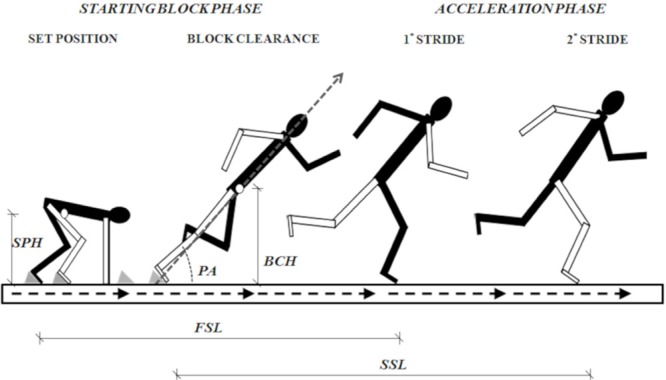

To analyze the efficiency of three different rear knee angles conditions, three critical events in the starting block phase (set position, pushing phase and block clearance) were identified, and the first and the second strides were considered to analyze the acceleration phase (Fig. 1). In this study the term “stride” is used to define a complete cycle, from foot contact to the next contact of that same foot. For both phases, different kinematic parameters were calculated using Matlab 7.1 (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

FIG. 1.

GRAPHIC REPRESENTATION ON SAGITTAL PLANE OF THE STARTING BLOCK PHASE AND ACCELERATION PHASE USED FOR THE KINEMATIC ANALYSIS.

Note: The geometric variables are shown in the graph: the set position height (SPH) and the block clearance height of COM (BCH), the push-off angle (PA), the first (FSL) and the second (SSL) stride length. In the graph the right limbs are in black and the left are in white.

Set Position

In order to assess the effect of the three rear knee angles on whole body posture in the starting block phase the height of the COM at the set position, namely set position height (SPH), was calculated.

Block Clearance

This event refers to the instant when the front foot leaves contact with the block [16]. At this event the horizontal velocity and height of the COM (block clearance velocity [BCV] and block clearance height [BCH]) were calculated.

To characterize the efficiency of the starting block phase and the pushing of the rear leg, the pushing phase event was analyzed. This event comprises the time from the first movement in the set position to block clearance. The duration of this event (block time), the pushing time on the rear block (PTRB) and the percentage of the pushing time on the rear block (%PTRB) were measured. The average force impulse (Fimpulse) and the average velocity of COM (VblockMean) were also calculated. Fimpulse was calculated as:

Fimpulse ≈ BCV x m

where BCV is the horizontal velocity of the COM at the block clearance (measured with the motion analysis system) and m is the body mass. Moreover, the push-off angle (PA) was taken between the horizontal and the line joining the COM to the front toe at block clearance (Fig. 1).

First and Second Strides

The lengths of the first two strides were measured: the first stride length (FSL) was the distance covered by the first metatarsal head marker on the rear leg between take-off from the block and first foot contact; the second stride length (SSL) was the distance covered by the first metatarsal head marker on the front leg between take-off, from the block and first foot contact (Fig. 1).

Furthermore, the velocity of the COM was taken at the first and second strides (FSV and SSV respectively), which indeed corresponded to the first and second foot take-off respectively.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 12.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Means and standard deviations were computed for each outcome variable. Repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to test the effect of rear knee angle (three levels: 90°, 115° and 135°) on horizontal velocity of the COM (three levels: BCV, FSV and SSV), the stride length (two levels: FSL and SSL) and COM height (two levels: SPH and BCH). One-way ANOVA was performed to test the effect of rear knee angle on PA, block time, PTRB, %PTRB and Fimpulse. The Mauchly test was used to validate the one-way ANOVA; in case the sphericity assumption was not met, the Huynh–Feldt correction for the degrees of freedom was applied. Levene's test was used to test the homogeneity of variance. The criterion alpha level for significance was set at p<0.05 for all analyses. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni post-hoc test when significant effects were found. The Games-Howell post-hoc test was used in case the population variances were unequal.

RESULTS

Preliminary analysis showed no significant differences for age, height and weight between females and males (p>0.3 for all; Mann-Whitney test). Hence, for the kinematic parameters analysis female and males were merged into a single group.

The results of kinematic variables analyzed are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3.

TABLE 1.

KINEMATIC VALUES FOR CENTRE OF MASS AT BLOCK CLEARANCE

| 90° | 115° | 135° | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block clearance | |||

| BCH (m) | 0.82 ± 0.05 ^ | 0.82 ± 0.04 ^ | 0.81 ± 0.04 |

| BCV (m ·s-1) | 2.67 ± 0.26°§ | 2.62 ± 0.23 | 2.56 ± 0.24 |

| PA (°) | 40.42 ± 2.74 | 40.23 ± 2.13 | 39.77 ± 2.50 |

Note: BCH = height of the centre of mass; BCV = horizontal velocity of centre of mass; PA= push-off angle.

p<0.05 vs. 115°

p<0.01 vs. 135°

p<0.001 vs. 135°.

TABLE 2.

KINEMATIC VALUES FOR CENTRE OF MASS DURING ACCELERATION PHASE (FIRST AND SECOND STRIDE)

| 90° | 115° | 135° | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSV (m·s-1) | 2.69 ± 0.31°§ | 2.61 ± 0.27 | 2.58 ± 0.30 |

| FSL (m) | 1.23 ± 0.12 | 1.22 ± 0.11 | 1.21 ± 0.13 |

| SSV (m·s-1) | 3.66 ± 0.29°§ | 3.63 ± 0.25 | 3.59 ± 0.29 |

| SSL (m) | 1.96 ± 0.17 | 1.94 ± 0.12 | 1.93 ± 0.17 |

Note: FSV and SSV = horizontal velocity at first and second foot contact, respectively; FSL and SSL = distance between take-off from the block and the first foot contact.

p<0.05 vs. 115°

p<0.001 vs. 135°.

TABLE 3.

KINEMATIC VALUES FOR CENTRE OF MASS DURING PUSHING PHASE

| Pushing phase | 90° | 115° | 135° |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLOCK TIME (s) | 0.354 ± 0.015 | 0.348 ± 0.016 | 0.355 ± 0.01 |

| PTRB (s) | 0.12 ± 0.01 ^ | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| PTRB (%) | 34.62 ± 3.60 ^ | 31.30 ± 3.52 | 28.65 ± 3.5 |

| VblockMean (m·s-1) | 1.44 ± 0.11 | 1.43 ± 0.08 | 1.36 ± 0.06 |

| F Impulse (N·s) | 175.00 ± 26.4 | 9 172.00 ± 25.4 | 9 168.35 ± 25. |

Note: PTRB = pushing time on the rear block; VblockMean = average velocity of centre of mass during pushing phase; Fimpulse=average force impulse.

p<0.01 vs. 135°.

The height of the COM at the set position (SPH) and at the block clearance (BCH) was 0.57 ± 0.03m and 0.82 ± 0.04 m, respectively. Statistical analysis revealed a significant main effect of the height of the COM at both SPH and BCH [F(1,10)=580.41, p<0.001], but no significant effect of the rear knee angle conditions. A significant interaction was found between SPH and BCH and the rear knee angle conditions [F(2,20)=12.47, p<0.001]. Post hoc comparisons showed that the 90° knee condition had lower SPH than 135° (p<0.01), whereas 90° and 115° knee conditions had higher BCH than 135° (p<0.01) (Table 1).

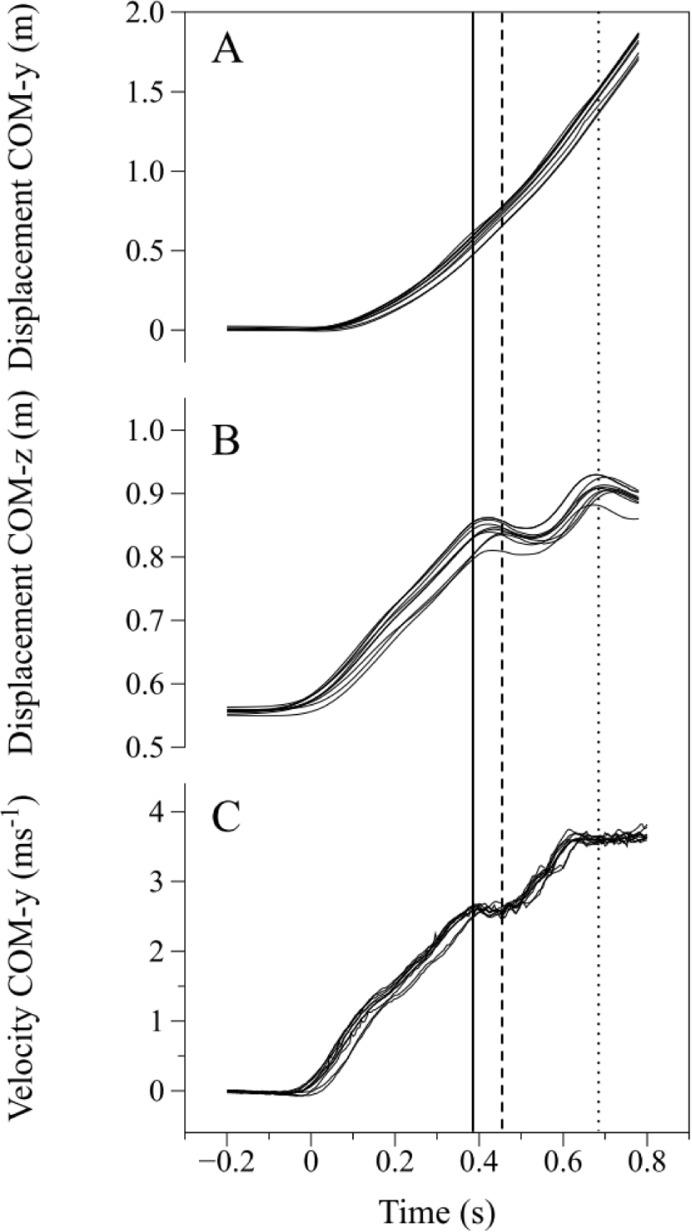

Fig. 2(A-C) shows a representative profile of the displacement of the COM in the anterior-posterior (A) and vertical direction (B), and the velocity profile of the COM in the anterior-posterior direction (C); the time instants of BCV, FSV and SSV are also indicated. The pattern profiles of the COM displacement and velocity were similar across the three angle conditions on the rear knee (90°, 115° and 135°) and trials.

FIG. 2.

AVE TIME PROFILES OF THE COM DISPLACEMENT IN THE ANTERO-POSTERIOR DIRECTION (Y) (A), IN THE VERTICAL DIRECTION (Z) (B) AND THE HORIZONTAL VELOCITY IN THE ANTERO-POSTERIOR DIRECTION (Y) ARE PRESENTED FOR THE SERIES OF TEN INDIVIDUAL TRIALS BY A REPRESENTATIVE SUBJECT FOR THE CONDITION OF THE KNEE REAR ANGLE AT 90°.

The solid, dashed, and dotted line represent the average block clearance velocity (BCV), the first stride velocity (FSV) and the second stride velocity (SSV), respectively, within the condition

The velocity profile of the COM during the first two strides was characterized by two peaks, which occurred at BCV and about 50 ms before the second stride, respectively (Fig. 2C).

BCV, FSV and SSV were 2.62 ± 0.24, 2.63 ± 0.29, 3.63 ± 0.27 m·s-1, respectively. The ANOVA test showed a significant effect of the block clearance, the first and second strides and knee angles (90°, 115° and 135°) on COM velocity [F(2,20)=53.58, p <0.001 and F(2,20)=17.46, p<0.001, respectively]. Pair-wise comparisons revealed no significant difference between BCV and FSV, whereas SSV was significantly higher than BCV and FSV (p<0.001). Regarding the rear knee angle conditions, pair-wise comparisons showed higher COM velocity at 90° vs 115° (p=0.039) and vs 135° (p <0.001) at the block clearance and along the two first strides (Tables 1 and Table 2).

The push-off angle (PA) was 40.42 ± 2.74, 40.24 ± 2.13 and 39.77 ± 2.50 degrees for the 90°, 115° and 135° knee angle condition, respectively (Table 1). One-way ANOVA revealed no significant difference among the three rear knee angle conditions.

No significant differences were found among the rear knee angle conditions for block time, average velocity of COM (VblockMean) and for Fimpulse, although the average values for VblockMean and for Fimpulse were greater at the 90° knee rear angle condition than at the 115° and 135° (Table 3).

The pushing time on the rear block (PTRB) was significantly different among rear knee angle conditions, as well as %PTRB, (F(2,20)=7.402, p=0.002; F(2,20)=7.742, p=0.002, respectively). Post hoc comparisons showed that the 90° knee condition had greater PTRB and %PTRB than 135° [p<0.01 for both (Table 3)].

Although the participants were not asked to perform the starting block trials covering the distance with the longest strides, all of them performed four strides within the 5 m of motion capture recording volume. The first stride length (FSL) and the second stride length (SSL) were 1.22 ± 0.12 m and 1.94 ± 0.15 m, respectively (Table 2). The ANOVA test showed a significant main effect between FSL and SSL [F(1,10)=1582.81, p<0.001], but no significant changes in the stride length due to different angle conditions. Pair-wise comparison showed that SSL was significantly longer than FSL at any knee angle conditions (p<0.001) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The present work was designed to examine the effects of different rear knee angle in the set position on kinematic performance outcomes during the sprint start. The study focused on block phases (set position, pushing phase and block clearance), and acceleration phase (first and second stride). The results reveal some interesting kinematic aspects of the rear leg technique influencing the sprint start in university-level sprinters.

A first finding is that horizontal COM velocity increased significantly at the block clearance (BCV) and along the first two strides (FSV, SSV) when switching from 135° to 115° and then to 90° rear knee angle (Tables 1, 2). The horizontal velocity is directly determined by Fimpulse. No significant difference was found among the three rear knee angle conditions for Fimpulse, although it was greater at 90° than 115° and 135° (Table 3). In accordance with classic mechanical physics, as impulse is equal to the product of force and time, an increased block velocity could be due to either an increase in the net propulsion force generated or to an increased push duration. In this study no difference in the duration (block time) of the applied force was found among the three rear angle conditions (Table 3), so it can be assumed that the greater horizontal block velocity and Fimpulse at 90° compared to the 115° and 135° knee angle condition may be due to an increased horizontal force production and not to an increase in the duration of the push against the blocks. Although force measurements were not taken in this study, it can be speculated that these findings indicate and reinforce the previous suggestions of Mero et al. [24] that the amount of horizontal force achieved is a more important factor than the time to produce it. In our sample the values of block clearance velocity (BCV), first stride velocity (FSV), second stride velocity (SSV) and Fimpulse (Tables 1-3) were lower than those of elite sprinters [21, 24, 28], and similar to those observed in the literature for less-than-elite sprinters [21, 27]. These results were expected given the lack of specific motor patterns adapted to the sprint task in the sample used for laboratory analysis. Therefore, the level of ability, technique and strength capacity could explain this difference. It is interesting to highlight that a 90° knee angle condition may be a strategy that allows sprinters to maximize his or her strength capacity the best.

The time and percentage of pushing of the rear leg (PTRB,%PTRB) were significantly different among the three rear knee angle conditions (Table 3). The results of the present study show a higher PTRB and %PTRB at 90° vs 115° and 135° condition (0.12 s vs 0.11 s and 0.09 s and 34.62% vs 31.30% and 28.65%, respectively). This suggests that a smaller knee joint angle allows the rear leg to contribute more to acceleration during the starting block phase; this appears to be associated with a powerful start (i.e. greater velocity achieved in less time) and, consequently, with a better performance.

The push-off angle (PA) at block clearance was similar in the three knee angle conditions (40.42° at 90°, 40.23° at 115° and 39.77° at 135°, Table 1). These values are in line with the range (from 32° to 42°) reported for skilled sprinters by Mero and colleagues [21, 24]. The angle between the horizontal and the line joining the COM to the toe at block clearance is an important parameter in achieving an optimum horizontal velocity; an angle below 50° ensures a lesser vertical and a greater horizontal component of COM velocity [14, 24]. However, the best PA in a sprint block start is a matter of debate; for example, Hoster and May [15] stated that the thrust angle during block clearance should be as low as possible in order to facilitate horizontal impulse generation; whereas Korchemny [18] suggests that the athlete should leave the blocks at a PA of 40°-50° because this would allow the athlete to attain a better transition phase. The data in this study revealed that knee rear angle does not influence the direction of force application.

A relevant parameter affecting body geometrical configuration during the starting block phase was the height of COM. In the general population the position of the centre of mass of the human body depends on gender. In our sample, the Mann-Whitney test showed no significant differences between females and males for the height of COM at the set position and the block clearance instants (p>0.2 for both), possibly because of similar height in the two genders.

In our sample the average height of COM at the set position (SPH) and the block clearance (BCH) were 0.57 and 0.82 m, respectively. These figures are in the range found in the literature, SPH: 0.48-0.66 m [1, 6, 7, 14, 27, 28], BCH: 0.70-0.83 m [27, 28]. Small but significant differences in SPH and BCH were found among rear knee angles; in particular SPH was lower at a 90° rear knee angle than a 135° angle and BCH was higher at 90° and 115° than 135°. The finding of higher BCH at 90° and 115° rather than 135° (Table 1) suggests that a smaller rear knee angle allows for a more effective transition phase since it is associated with higher block clearance velocity and velocity of the first two strides. A smaller rear knee angle also results in a BCH closer to that of elite sprinters [28]. However, it should be noted that a great amount of variability in SPH and BCH exists among athletes and these parameters do not seem to be determinant in general sprint performance.

After take-off from the blocks, a runner accelerates by increasing stride length and stride rate. The second stride length (SSL) was significantly longer than the first stride length (FSL) irrespective of the rear knee angle condition (Table 2), but there were no significant differences among the three rear knee angle conditions. The increase in length during the first strides from the block has been advocated as part of an optimal start [18]. In this study the average lengths of the first (FSL) and second stride (SSL) were 1.22 and 1.94 m, respectively; the first figure is within the range [1] found in male world-class sprinters (1.13-1.42 m), while the second figure is at the lower limit (1.97-2.31 m). The low value of the SSL was expected in our group, as stride length is a complex parameter that depends on many factors including the efficiency of biochemical energetic processes in working muscles and the intramuscular coordination of agonists and antagonists. Coordination and strength capacity should be improved considerably with resistance training [8], inducing an increase in muscle strength associated with neural adaptation and muscular hypertrophy. Therefore, in sprinters, integration of both technical aspects and strength conditioning training sessions is suggested.

The findings of the present study indicate that, among the measured kinematic parameters BCV, FSV and SSV, the time of pushing of the rear leg and its percentage were mainly affected by the rear knee angle. Thus it can be suggested that a 90° rear knee angle at the set position could be a strategy to facilitate the push action of the rear leg in sprinters.

CONCLUSIONS

In a sprint start, coaches and athletes aim to achieve an optimum set position in order to enable the maximum block velocity. Achieving an optimal movement stereotype is a long-term process; therefore a proper training methodology is critically needed to guide lesser skilled sprinters to their best performance level. The results of this study suggest that coaches and athletes should pay more attention to the rear knee angle during the training process in order to reach a high horizontal velocity during the starting block phase and the acceleration phase. In particular, these findings provide some direction and useful practical advice in defining an efficient rear leg biomechanical configuration at the set position. Moreover, it would be interesting to explore whether a higher level of sprint performance might be achieved with the 90° rear knee angle condition confirming the strategy assumed by some elite sprinters. It would also be worth examining musculoskeletal properties through electromyographic analysis with the 90° rear knee angle in an attempt to better understand the influence of lower limb muscles that have an impact on the technique of rear leg action.

Conflict of interest

none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atwater A. Kinematic analysis of sprinting. Track Field Q. Rev. 1982;82:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann W. Sprint start characteristics of female sprinters. In: Ayalon A, editor. Proceedings of an International Seminar in Biomechanics of Sport Games and Sport Activities, Wingate Institute, Israel. 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezodis N.E, Salo A.I, Trewartha G. Choise of sprint start performance measure affects the performance-based ranking within a group of sprinters: which is the most appropriate measure? Sports Biomech. 2010;9:258–269. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2010.538713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borzov V. Optimal starting position. Mod. Athlete. Coach. 1980;18:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw E.J, Maulder P.S, Keogh W.L. Biological movement variability during the sprint start: Performance enhancement or hindrance? Sports Biomech. 2007;6:246–260. doi: 10.1080/14763140701489660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Čoh M, Jošt B, Škof B, Tomažin K, Dolence A. Kinematic and kinetic parameters of sprint start and start acceleration model of top sprinters. Gymnica. 1998;28:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Čoh M, Tomažin K. Kinematic analysis of the sprint start and acceleration from the blocks. New. Stud. Athletics. 2006;21:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delecluse C. Influence of strength training on sprint running performance. Current findings and implications for training. Sports Med. 1997;24:147–156. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dempster W.T. Space requirements of the seated operator. US Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, WADC Technical Rep. 1995:55–159. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortier S, Basset F.A, Mbourou G.A, Favérial J, Teasdale N. Starting block performance in sprinters: a statistical method for identifying discriminative parameters of effect of providing feedback over a 6-week period. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2005;4:134–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagnon M.A. Kinetic analysis of the standing starts in female sprinters of different ability. In: Asmussen E, Jorgensen K, editors. Biomechanics VI –B. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1978. pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guissard N, Duchateau J. Electromyography of the sprint start. J Hum Movement Studies. 1990;18:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harland M.J, Andrews M.H, Steele J.R. Instrumented start blocks: A quantitative coaching aid. In: Bauer T. Ontario., editor. XIII International Symposium for Biomechanics in Sport. 1995. pp. 367–370. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harland M.J, Steele J.R. Biomechanics of the sprint start. Sports Med. 1997;23:11–20. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199723010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoster M, May E. Notes on the biomechanics of the sprint start. Athl. Coach. 1979;13:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kistler J.W. Study of the distribution of the force exerted upon the blocks in starting the sprint from various starting positions. Res. Q. 1934;5(Suppl 1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knapik J.T, Wright J.E, Mawdsley R.H, Braun J. Isometric, isotonic, and isokinetic torque variations in four muscle groups through a range of joint motion. Phys. Ther. 1983;63:938–947. doi: 10.1093/ptj/63.6.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korchemny R. A new concept for sprint start and acceleration training. New Stud Athletics. 1992;7:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraan G.A, van Veen J, Snijders C.J, Storm J. Starting from standing;why step backwards? J. Biomech. 2001;34:211–215. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuitunen S, Komi P.V, Kyrolainen H. Knee and ankle joint stiffness in sprint running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002;34:166–173. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mero A. Force-time characteristics and running velocity of male sprinters during the acceleration phase of sprinting. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 1988;59:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mero A, Komi P.V. Reaction-time and electromyography activity during a sprint start. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990;61:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00236697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mero A, Kuitunen S, Harland M, Kyrolainen H, Komi P.V. Effects of muscle-tendon length on joint moment and power during sprint starts. J. Sports Sci. 2006;24:165–173. doi: 10.1080/02640410500131753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mero A, Luhtanen P, Komi P.V. A biomechanical study of the sprint start. Scand. J. Sports Sci. 1983;5:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray M.P, Gardner G.M, Mollinger L.A, Sepic S.B. Strength of isometric and isokinetic contractions: Knee muscles of men aged 20 to 86. Phys. Ther. 1980;60:412–419. doi: 10.1093/ptj/60.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natta F, Breniere Y. Influence the la posture initiale sur la dynamique du dèpart de sprint en starting-blocks. Sci. Motricitè. 1998;34:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schot P.K, Knutzen K.M. A biomechanical analysis of four sprint start positions. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 1992;63:137–147. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slawinski J, Bonnefoy A, Levêque J.M, Ontanon G, Riquet A, Dumas R, Chèze L. Kinematic and kinetic comparisons of elite and well-trained sprinters during sprint start. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010;24:896–905. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ad3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tellez T, Doolittle D. Sprinting from start to finish. Track Technique. 1984;88:2802–2805. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Coppenolle H, Delecluse C, Goris M, Bohets W, Vanden Eynde E. Technology and development of speed: evaluation of the start, sprint and body composition of Pavoni, Cooman and Desruelles. Athl Coach. 1989;23:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winter A.D. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement’. Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. 3rd edition 2005. [Google Scholar]