Abstract

Background

Genetic alterations have been identified in melanomas according to different levels of sun exposure. Whereas the conventional morphology-based classification provides a clue for tumor growth and prognosis, the new classification by genetic alterations offers a basis for targeted therapy.

Objective

The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the biological behavior of melanoma subtypes and compare the two classifications in the Korean population.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed on patients found to have malignant melanoma in Severance Hospital from 2005 to 2012. Age, sex, location of the tumor, histologic subtype, tumor depth, ulceration, lymph node invasion, visceral organ metastasis, and overall survival were evaluated.

Results

Of the 206 cases, the most common type was acral melanoma (n=94, 45.6%), followed by nonchronic sun damage-induced melanoma (n=43, 20.9%), and mucosal melanoma (n=40, 19.4%). Twenty-one patients (10.2%) had the chronic sun-damaged type, whereas eight patients (3.9%) had tumors of unknown primary origin. Lentigo maligna melanoma was newly classified as the chronic sun-damaged type, and acral lentiginous melanoma as the acral type. More than half of the superficial spreading melanomas were newly grouped as nonchronic sun-damaged melanomas, whereas nodular melanoma was rather evenly distributed.

Conclusion

The distribution of melanomas was largely similar in both the morphology-based and sun exposure-based classifications, and in both classifications, mucosal melanoma had the worst 5-year survival owing to its tumor thickness and advanced stage at the time of diagnosis.

Keywords: Korean, Melanoma, Morphologic feature, Ultraviolet irradiation

INTRODUCTION

The increasing incidence of melanoma and the difficulty to treat this disease has led to many researches in melanoma. Conventionally, cutaneous melanoma has been distinguished according to four main types based on morphology and histology1, superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), nodular melanoma (NM), and acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), by using the World Health Organization classification2. After the skin, melanoma is most likely to arise in the juxtacutaneous mucous membranes, such as the oral mucosa, nasal sinuses, vagina, and anorectal mucosa3. Mucosal melanomas are similar to acral melanomas in histologic appearance and aggressiveness, which has led to the use of the histologic term mucosal lentiginous melanoma4. Mucosal melanoma is another common variant other than cutaneous melanoma.

Recently, genetic alterations such as BRAF and KIT mutations have been identified in melanomas according to different levels of sun exposure, and a new set of classification has been established5. On the basis of the anatomic location of the tumor and the degree of ultraviolet (UV) exposure, melanoma is classified into four subtypes: (1) melanomas that occur on skin without chronic sun-induced damage (non-CSD); (2) melanomas on skin with chronic sun-induced damage (CSD); (3) mucosal melanomas; and (4) acral melanomas2,5. Melanoma of unknown primary site is a unique entity of melanoma that develops in a lymph node, subcutaneous tissues, or visceral organ without a primary lesion6.

Whereas the conventional morphology-based classification provides a clue for tumor growth and characteristics, the new classification by genetic alterations offers a basis for targeted therapy, such as with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (PLX4032) or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (formerly known as STI571)7.

The purpose of this study is to compare the distribution of the subtypes according to both classifications and demonstrate the biological behavior of melanoma subtypes in the Korean population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical records of 206 patients who had been found to have and were treated for malignant melanoma in Severance Hospital (Seoul, Korea) between 2005 and 2012. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Yonsei University, Severance Hospital (IRB No. 4-2012-0165). Clinical data were available in all cases.

Clinicopathological data

Age, sex, location of the tumor, tumor depth, ulceration, lymph node invasion, visceral organ metastasis, treatment modality, and overall survival (OS) were evaluated. Tumor thickness was measured according to Breslow thickness, and OS was defined as the time from the day of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Melanomas were classified by using both the classification that was based on the morphology of the tumor and that suggested by Curtin et al.5 in 2005 according to the level of sun exposure.

The staging was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines for melanoma at the time of diagnosis8. The AJCC Melanoma Staging Database divides melanoma into four stages: localized melanoma (stages I and II), regional metastatic melanoma (stage III), and distant metastatic melanoma (stage IV).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by using PASW Statistics 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc ver. 12.7.4 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium). Categorical data were described by using numbers and percentages. The 5-year survival and OS of the patients were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared by using the log-rank test. All tests were two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Melanoma subtypes in the Korean population

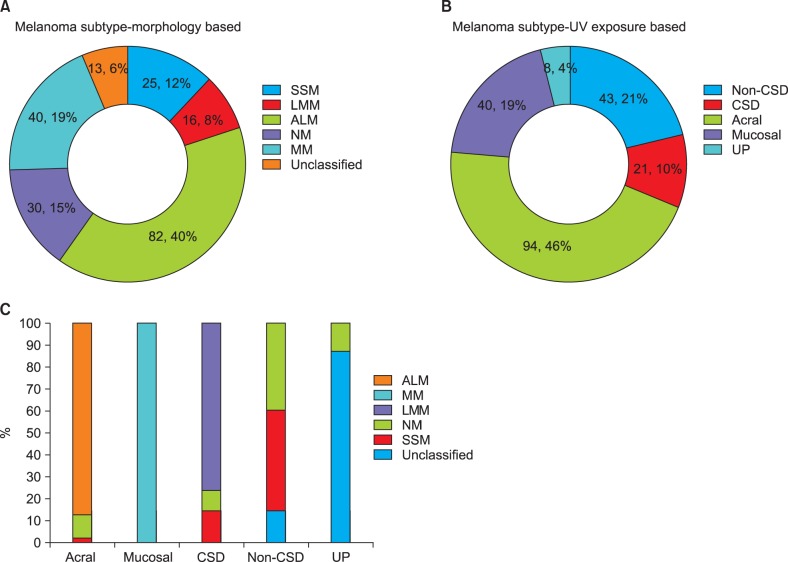

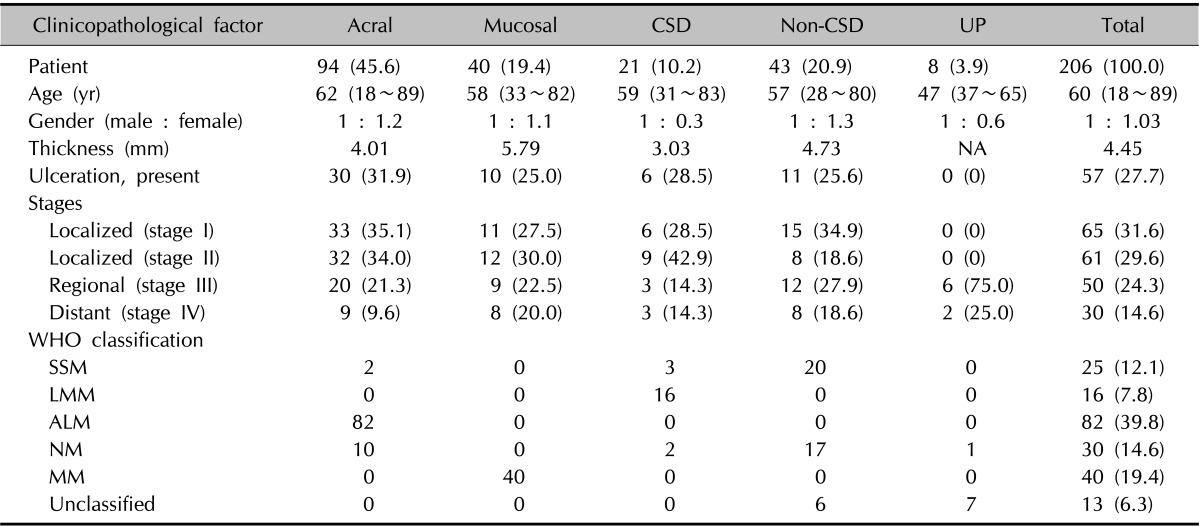

Of the 206 cases, the most common type was acral melanoma (n=94, 45.6%) followed by the non-CSD type (n=43, 20.9%) and mucosal melanoma (n=40, 19.4%). Twenty-one patients (10.2%) had the CSD type, whereas eight patients (3.9%) had tumors of unknown primary origin (Table 1, Fig. 1). The unknown primary origin type was diagnosed in patients who had an initial presentation of melanoma in the lymph nodes, subcutaneous tissue, or visceral organ without a known primary site6.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinicopathological factors

Values are presented as number (%), median (range), or number only.

CSD: chronic sun-induced damage, UP: unknown primary, NA: not applicable, SSM: superficial spreading melanoma, LMM: lentigo maligna melanoma, ALM: acral lentiginous melanoma, NM: nodular melanoma, MM: mucosal melanoma.

Fig. 1.

(A) Melanoma subtypes based on morphology and histology. (B) Melanoma subtypes based on the level of ultraviolet (UV) exposure. (C) Proportion of conventional histologic subtypes in the UV exposure-based classification. SSM: superficial spreading melanoma, LMM: lentigo maligna melanoma, ALM: acral lentiginous melanoma, NM: nodular melanoma, MM: mucosal melanoma, CSD: chronic sun-induced damage, UP: unknown primary.

The median age of patients with the acral type was 62 years (range, 18~89 years), ranking as the oldest median age among the subtypes, whereas patients with tumors of unknown primary origin had the youngest median age of 47 years. The other subtypes showed no significant differences. The male-to-female ratio of the total included patients was 1 : 1.03. The ratio was increased more than threefold in the CSD type, whereas the other types did not show such a gap (Table 1).

The mucosal type was the thickest subtype (thickness, 5.79 mm), followed by the non-CSD type (4.73 mm), acral type (4.01 mm), and CSD type (3.03 mm). With the classification based on the morphology and histology, NM showed a Breslow thickness of 6.86 mm, ALM 3.34 mm, LMM 2.84 mm, and SSM 1.72 mm.

In the CSD type, 71.4% of the patients had localized melanoma (stages I and II), whereas in the non-CSD and mucosal types, localized melanoma was seen less frequently (53.5% and 57.5% of the patients, respectively) (Table 1).

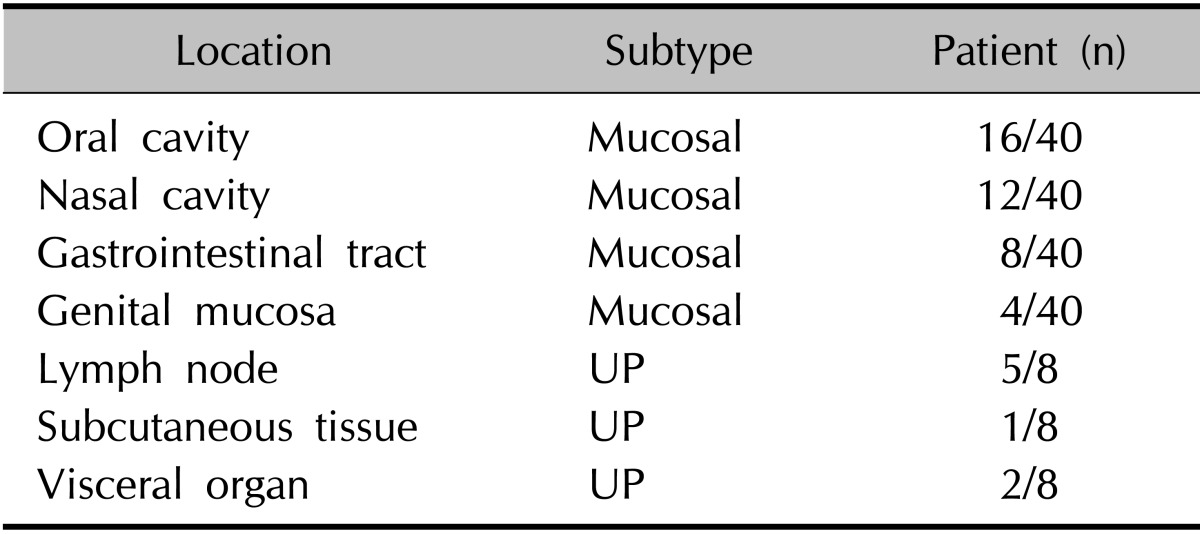

Anatomic location of mucosal melanoma and melanoma of unknown primary origin

Among the 40 cases of mucosal melanoma, 16 were melanoma arising from the oral cavity, such as the buccal mucosa and gingiva, whereas 12 were melanoma arising from the nasal cavity, such as the nasal mucosa or nasopharynx. Eight patients had melanoma from the gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and rectum), and four patients had melanoma from the genital mucosa (vagina and vulva) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anatomaic location of mucosal melanoma and melanoma of unknown primary origin

UP: melanoma of unknown primary origin.

Of the eight cases of melanoma from unknown origin, five cases were arising from a lymph node, one arising from the subcutaneous tissue of the trunk, and two were from a visceral organ such as the spine and the brain (Table 2).

Comparison of the two classifications

All of the LMM cases were newly classified as the CSD type, and all of the ALM cases were classified into the acral type. Of the SSMs, 80.0% (20 of 25) were newly grouped as the non-CSD type. However, NM seemed to be rather evenly distributed. Among the 30 NM patients, 17 patients (56.7%) were grouped into the non-CSD type, 10 patients (33.3%) into the acral type, 2 patients (6.7%) into the CSD type, and 1 patient (3.3%) into the unknown primary origin type (Table 1). The unclassified types include melanomas such as desmoplastic melanoma and spitzoid melanoma, and these unclassified types were reclassified into the non-CSD type (n=6, 46.1%) and the unknown primary type (n=7, 53.8%) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

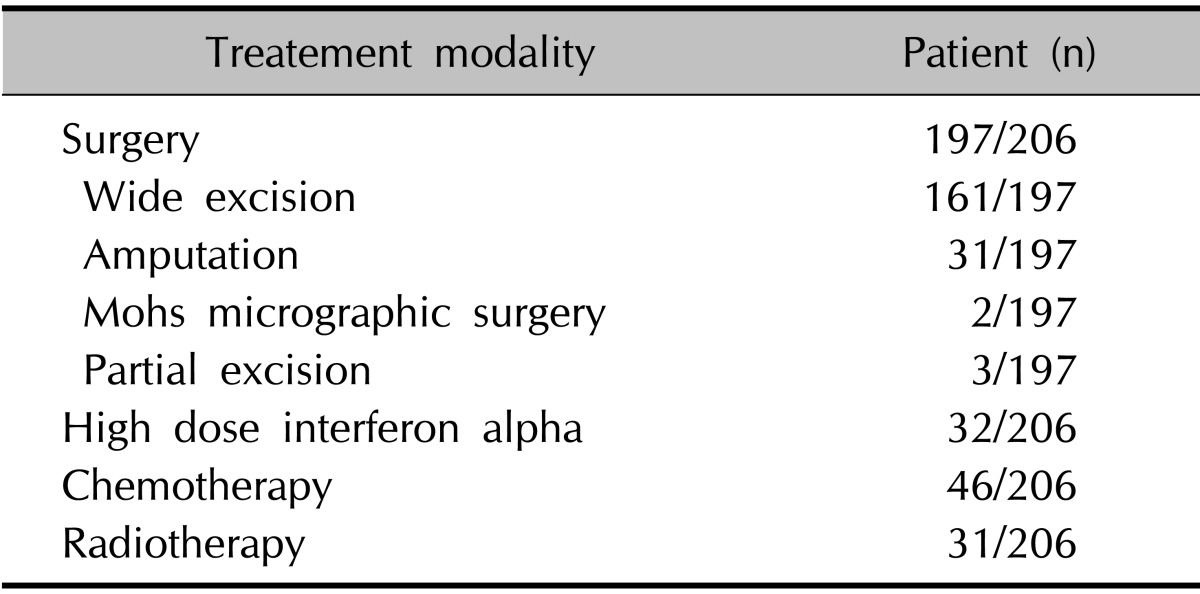

Melanoma treatment

Most of the patients found to have malignant melanoma received operation in variable manners. Excluding 9 patients who were unable to undergo surgery owing to their poor general condition, 197 patients (95.6%) received surgery under general anesthesia. Most of the patients (n=161, 78.1%) underwent wide excision, whereas amputation was done in 31 patients (15.0%). Two patients with LMM had Mohs micrographic surgery, and three patients had partial excision of the melanoma but not complete excision owing to the metastatic site, such as the spine or chest wall (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment modality of the melanoma patients

In addition to surgery, 32 patients had high-dose interferon-α treatment, 46 patients had a chemotherapy regimen of dacarbazine, and 31 patients with metastasis in such sites as the spine or head and neck received radiotherapy (Table 3). Many patients received a combination of more than one systemic therapy. As this study was a retrospective study in which the patients were enrolled between 2005 and 2012 and followed until 2012 December, no patients were treated with targeted therapy such as the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib.

Survival of the subtypes in Korean population

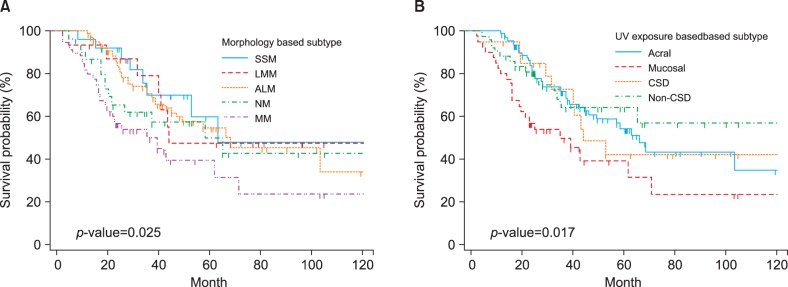

Concerning patient survival, mucosal melanoma had the worst 5-year survival in both classifications (p<0.05), owing to its tumor thickness and advanced stage at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 2). The median survival of the total enrolled patients was 61 months, whereas mucosal melanoma patients had the shortest median survival of 34 months. Mucosal melanoma had a hazard ratio of 2.07 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12~3.82) compared with acral melanoma, and a hazard ratio of 2.25 (95% CI, 1.12~4.53) compared with non-CSD melanoma. In the morphology-based classification, mucosal melanoma had a hazard ratio of 2.23 (95% CI, 1.09~4.84) compared with SSM, and a hazard ratio of 2.12 (95% CI, 1.15~3.89) compared with ALM.

Fig. 2.

(A) Five-year survival curve of subtypes according to morphology-based classification. (B) Five-year survival curve of subtypes according to ultraviolet (UV) exposure-based classification. SSM: superficial spreading melanoma, LMM: lentigo maligna melanoma, ALM: acral lentiginous melanoma, NM: nodular melanoma, MM: mucosal melanoma, CSD: chronic sun-induced damage.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of melanoma has increased significantly worldwide during the last several decades. As the classic consensus for diagnosing melanoma is based on histopathologic evaluation of biopsy specimens1, melanoma has been classified according to the morphological and architectural features of the tumor2.

In Caucasian data, SSM is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 70% of all cutaneous melanomas9. However, in Asians, ALM is the most common type, accounting for roughly 45%~66%10. Our data (Fig. 1) show that ALM has the highest incidence, which is consistent with previous data in Korean melanoma patients11.

Among the risk factors of melanoma, the most important factor is known to be a history of periodic and intense sun exposure during childhood and adolescence12. Considering that UV light exposure is an inseparable factor for melanoma development, Curtin et al.5 reported in 2005 that there are distinct sets of genetic alternations in melanoma with different susceptibilities to UV exposure.

Curtin et al.5 divided the types according to the level of UV exposure: (1) melanomas that occur on skin with non chronic sun damage; (2) melanomas on skin with chronic sun damage; and melanomas that arise without obvious exposure to light, which include (3) mucosal melanomas and (4) acral melanomas.

In the Caucasian data of 1,112 cases by Greaves et al.13, the non-acral cutaneous type, which refers to the non-CSD and CSD types, constituted 69.6%, whereas the acral type constituted only 10%. In the Chinese data of 502 cases representing the Asian population, the most prevalent type was the acral type (38.4%) followed by the mucosal type (33.3%)7. There is a noticeable difference in the proportion of melanoma subtypes in Caucasian and Asian populations, and the finding of our study was consistent with the Chinese data (Fig. 1).

The single most important prognostic factor for survival in localized melanoma is tumor thickness, measured from the top of the granular layer to the greatest depth of tumor invasion14. It is well known that NM often lacks a radial growth phase and thus presents with rapid evolution15; consistent with these facts, NM had the thickest Breslow thickness (6.86 mm) in our study. Although mucosal melanoma had a Breslow thickness of 5.79 mm, it had a greater proportion of advanced-staged tumors (stage 3 and stage 4: 42.5%) than NM (stage 3 and stage 4: 36.5%) and showed the worst prognosis among the subtypes in the morphology-based classification and also in the UV exposure-based classification.

In summary, this study reveals that the two classifications share many cases in common, such as cases of ALM with the acral type and LMM with the CSD type. On the basis of the tumor-node-metastases (TNM) stage, mucosal melanoma was associated with poor prognosis in Korean melanoma patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0022376).

References

- 1.McGovern VJ, Mihm MC, Jr, Bailly C, Booth JC, Clark WH, Jr, Cochran AJ, et al. The classification of malignant melanoma and its histologic reporting. Cancer. 1973;32:1446–1457. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197312)32:6<1446::aid-cncr2820320623>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, Lasithiotakis K, Garbe C, Pinkel D, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey M, Mathew A, Abraham EK, Ahamed IM, Nair KM. Primary malignant melanoma of the mucous membranes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1998;24:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(98)80011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elder DE, Jucovy PM, Tuthill RJ, Clark WH., Jr The classification of malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:315–320. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198000240-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasgupta T, Bowden L, Berg JW. Malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1963;117:341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong Y, Si L, Zhu Y, Xu X, Corless CL, Flaherty KT, et al. Large-scale analysis of KIT aberrations in Chinese patients with melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1684–1691. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon SE, Cho KH, Hwang JH, Kim JA, Youn JI. A statistical study of cutaneous malignant tumors. Korean J Dermatol. 1998;36:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roh MR, Kim J, Chung KY. Treatment and outcomes of melanoma in acral location in Korean patients. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:562–568. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titus-Ernstoff L, Perry AE, Spencer SK, Gibson JJ, Cole BF, Ernstoff MS. Pigmentary characteristics and moles in relation to melanoma risk. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:144–149. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greaves WO, Verma S, Patel KP, Davies MA, Barkoh BA, Galbincea JM, et al. Frequency and spectrum of BRAF mutations in a retrospective, single-institution study of 1112 cases of melanoma. J Mol Diagn. 2013;15:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3622–3634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demierre MF, Chung C, Miller DR, Geller AC. Early detection of thick melanomas in the United States: beware of the nodular subtype. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:745–750. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]