Abstract

In a search of new compounds active against cancer, synthesis of a series of C-5 curcumin analogues was carried out. The new compounds demonstrated good cytotoxicity against chronic myeloid leukemia (KBM5) and colon cancer (HCT116) cell lines. Further, these compounds were found to have better potential to inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in comparison to curcumin, which show their potential to act as anti-inflammatory agents. Some compounds were found to show higher cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines in comparison to curcumin used as standard.

1. Introduction

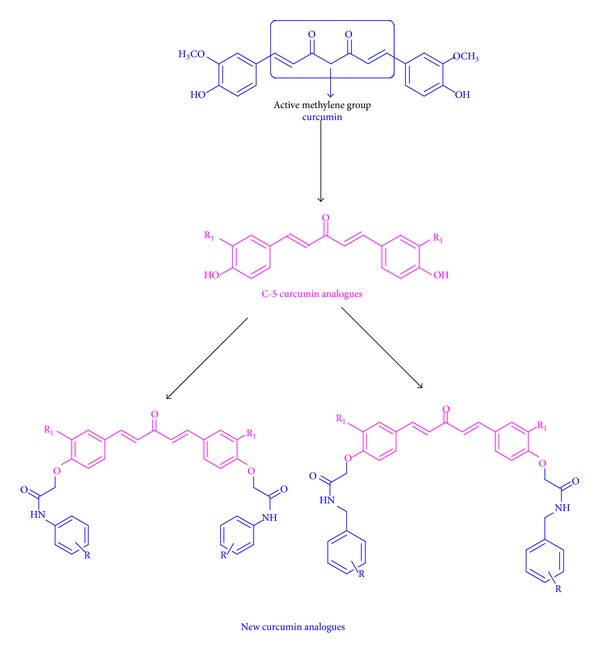

In the last few decades, importance has been given to biologically active natural products as these compounds generally do not have any side effects. The proof of this is the fact that more than 62% of the anticancer drugs approved from 1983 to 1994 are either natural products or natural product analogues [1]. Curcumin and related compounds, termed as curcuminoid, are among the compounds of great interest due to their wide range of biological activities [2–12]. Curcumin ability to inhibit the growth of various types of cancer cells at various stages of cancer progression is due to its potential to act on multiple targets [13–17]. The β-diketone is the structural feature responsible for rapid metabolism of curcumin by aldo-keto reductase in liver [18]. Tremendous research work has been done to improve the bioavailability and absorption of curcumin [19]. Further, in vivo and in vitro studies showed that curcumin undergo rapid metabolism by oxidation, reduction, glucuronidation, and sulfation [20, 21], which occur at 4-OH [22]. In a rational approach to design new curcumin analogues the facts to be taken under consideration are modification of β-diketone moiety and blocking 4-OH of curcumin analogues. In efforts to improve the activity and stability of curcumin analogues, C-5 curcumins have been designed and synthesized by various research groups [23, 24]. It has been reported that C-5 curcumin analogues show better activity and stability in in vitro and in vivo studies [25]. Yamakoshi et al. have done SAR studies on C-5 curcumin analogues. Important outcomes of their studies were that symmetry is important in case of tetrasubstituted C-5 curcumin analogues and 4-position is a possible site for attaching probe to enhance activity [26]. In search of new molecules with good cytotoxicity against cancer cells we planned to synthesize new C-5 curcumin analogues and selected amido-ether linker for blocking 4-OH (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modification of curcumin to get new C-5 curcumin analogues.

As a part of our research work towards development of biologically important hybrid molecules [27], we designed new curcumin analogues. In present work, we report synthesis, theoretical prediction of physicochemical properties, cytotoxicity, and inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation of C-5 curcumin analogues (3a–3p) in human cancer cell lines. New hybrid molecules demonstrated varying level of cytotoxicity against KBM5 and HCT116 cancer cell lines with some compounds being more active than curcumin against both cell lines. Also compounds were found to inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

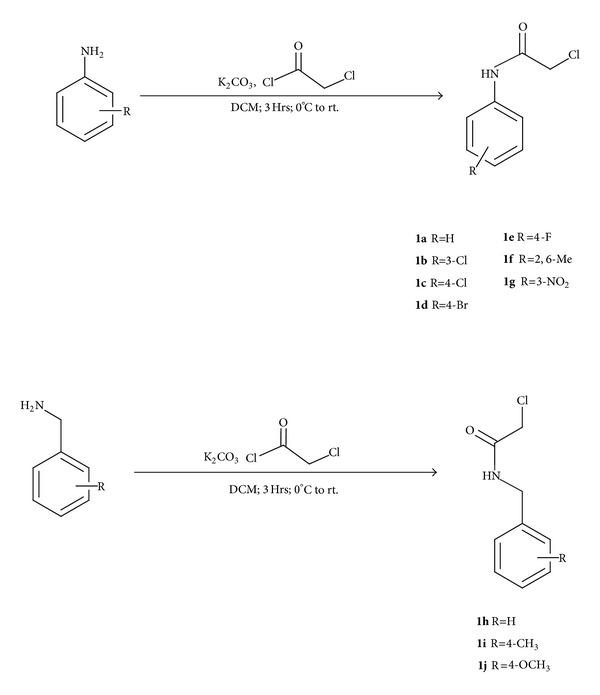

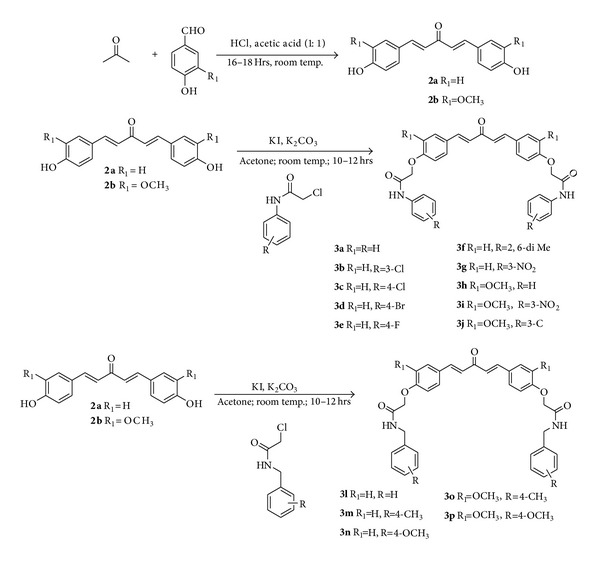

The C-5 curcumin analogues were synthesized by multistep synthesis process. The amido-ether linkers (1a–1j) were synthesized by reaction of respective aromatic amines/benzyl amines with chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of K2CO3 as base and dichloromethane as solvent (Scheme 1). C-5 curcumin analogues (2a, 2b) were synthesized by reaction of 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde/vanillin with acetone in the presence of 1 : 1 acetic acid/HCl solvent as well as catalyst. The C-5 curcumin analogues (2a, 2b) were further reacted with amido-ether linkers (1a–1j) in the presence of K2CO3 as base and acetone as solvent to obtain the desired hybrid molecules (3a–3p) in good yields (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

2.2. Biology

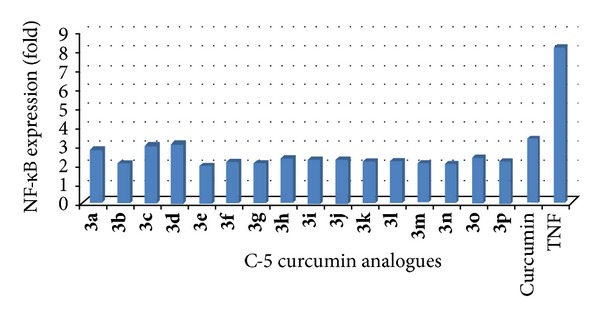

All C-5 curcumin analogues were tested for their cytotoxicity on chronic myeloid leukemia (KBM5) and colon cancer (HCT116) cell lines. However, the cytotoxicity pattern of all analogues was similar for both cell lines (Table 1). In C-5 curcumin nucleus variations were done by substituting –H by –OMe whereas in amido-ether linker substituted aromatic amide and benzylamide derivatives were used. In the case of curcumin analogues with aromatic amides (3a–3k), halogen substituents did not give fruitful results (3c, 3d, 3e) except for compounds 3b and 3k with chloro substituent at 3 and 4 positions, respectively, which demonstrated cytotoxicity better than curcumin in both cancer cell lines. The compounds without any substitution (3a, 3h) were found to be more active than the curcumin but the compound with −OMe group on C-5 curcumin ring (3h) was found most active. Substitution by nitro group in aromatic ring (3g, 3i) resulted in compounds with poor activity. Substitution by methyl groups at the 2,6-positions gave promising results in the case of molecule with –OMe substituent on C-5 curcumin ring (3j) but molecule without any substituent in C-5 curcumin ring demonstrated poor activity (3f). In case of curcumin analogues with benzylamide derivatives the hybrid molecule with –OMe substitution in aromatic ring as well as C-5 curcumin nucleus demonstrated potent activity (3p) whereas other compounds without any substituent (3l) or with –Me (3m, 3o) and –OMe (3n) substituents on aromatic ring exhibited poor cytotoxicity. The newly synthesized compounds were also screened for their potential to inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation (Figure 2). All molecules demonstrated higher potential to inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in comparison to curcumin from which it could be concluded that these compounds can act as very good anti-inflammatory agents.

Table 1.

Inhibition of hybrid molecules (3a–3p) on chronic myeloid leukemia (KBM5) and colon cancer (HCT116) cell lines at 5 μM.

| Compound | Percentage growth inhibition KBM5 | Percentage growth inhibition HCT116 | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 76.06 ± 1.45 | 52.71 ± 1.01 | High |

| 3b | 85.52 ± 0.66 | 57.88 ± 0.45 | High |

| 3c | 29.38 ± 2.14 | 20.36 ± 1.48 | Moderate |

| 3d | 36.32 ± 4.30 | 25.17 ± 2.98 | Moderate |

| 3e | 30.09 ± 3.01 | 20.85 ± 2.08 | Moderate |

| 3f | 16.33 ± 4.84 | 11.32 ± 3.36 | Low |

| 3g | 8.65 ± 7.12 | 5.99 ± 4.94 | Low |

| 3h | 86.76 ± 3.09 | 60.13 ± 2.14 | High |

| 3i | 17.67 ± 1.54 | 12.25 ± 1.07 | Low |

| 3j | 87.61 ± 3.43 | 60.72 ± 2.38 | High |

| 3k | 75.09 ± 2.90 | 52.04 ± 2.01 | High |

| 3l | 22.33 ± 3.82 | 15.48 ± 2.65 | Moderate |

| 3m | 13.27 ± 2.08 | 9.20 ± 1.44 | Low |

| 3n | 23.27 ± 1.84 | 16.12 ± 1.28 | Moderate |

| 3o | 10.89 ± 4.25 | 7.55 ± 2.95 | Low |

| 3p | 83.63 ± 0.34 | 57.96 ± 0.24 | High |

| Control | 0.00 ± 3.36 | 0.00 ± 2.33 | |

| Curcumin | 46.00 ± 1.49 | 46.87 ± 1.03 |

Compounds are classified based on potential to inhibit growth of KBM5 cancer cell lines at 5 μM, >60%; high activity, >20%; moderate activity, <20%; low activity.

Figure 2.

Downregulation of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in KBM5 cells. KBM-5 cells were incubated with 5 μM dose of tested compounds for 8 h and then treated with 0.1 nM TNF-α for 30 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared and assayed for NF-κB activation using EMSA. The fold downmodulation of NF-κB as compared to TNF-α is shown.

2.3. Theoretical Predictions of Physicochemical Properties [28–31]

Molinspiration and Osiris software were used for theoretical prediction of physicochemical properties of the new hybrid molecules. The methodology developed by molinspiration is used to calculate m ilogP (octanol/water partition coefficient). Total polar surface area (TPSA) has been reported to be a very good descriptor of various characteristics of compound such as absorption, including intestinal absorption, bioavailability, Caco-2 permeability, and blood brain barrier penetration. Theoretical molecular properties, predicted by molinspiration software, for new C-5 curcumin analogues (3a–3p) are tabulated in Table 2. The values of lipophilicity (log P) and total polar surface area (TPSA) are two important parameters for the prediction of oral bioavailability of drug molecules [32, 33]. It has been reported that molecules with TPSA values of 140 Å2 or more are likely to exhibit poor intestinal absorption [33].

Table 2.

Molinspiration calculations of new curcumin analogues (3a–3p).

| Compound | Molecular properties calculations | Drug likeness properties predictions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.W. | m ilogP | TPSA Å2 | OH–NH interaction | N violation | Vol. | GPCR | ICM | KI | NRL | PI | EI | |

| 3a | 532 | 5.905 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 486 | −0.12 | −0.50 | −0.25 | −0.12 | −0.08 | −0.17 |

| 3b | 601 | 7.213 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 513 | −0.17 | −0.65 | −0.35 | −0.24 | −0.12 | −0.29 |

| 3c | 601 | 7.261 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 513 | −0.16 | −0.65 | −0.35 | −0.23 | −0.11 | −0.41 |

| 3d | 690 | 7.523 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 522 | −0.22 | −0.69 | −0.37 | −0.29 | −0.15 | −0.30 |

| 3e | 568 | 6.232 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 496 | −0.16 | −0.66 | −0.33 | −0.21 | −0.10 | −0.27 |

| 3f | 588 | 5.634 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 552 | −0.28 | −0.88 | −0.50 | −0.39 | −0.19 | −0.17 |

| 3g | 622 | 5.775 | 185 | 2 | 3 | 5.33 | −0.45 | −1.11 | −0.75 | −0.66 | −0.26 | −0.60 |

| 3h | 592 | 5.085 | 112 | 2 | 2 | 537 | −0.27 | −0.88 | −0.49 | −0.42 | −0.15 | −0.42 |

| 3i | 682 | 4.954 | 263 | 2 | 2 | 584 | −0.85 | −1.74 | −1.28 | −1.25 | −0.56 | −1.13 |

| 3j | 648 | 4.814 | 112 | 2 | 1 | 603 | −0.59 | −1.42 | −0.94 | −0.89 | −0.40 | −0.82 |

| 3k | 661 | 6.440 | 112 | 2 | 2 | 564 | −0.39 | −1.11 | −0.69 | −0.63 | −0.25 | −0.61 |

| 3l | 560 | 5.307 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 520 | −0.11 | −0.61 | −0.34 | −0.29 | 0.02 | −0.22 |

| 3m | 588 | 6.204 | 93 | 2 | 2 | 553 | −0.22 | −0.84 | −050 | −0.46 | −0.05 | −0.39 |

| 3n | 620 | 5.421 | 112 | 2 | 2 | 571 | −0.34 | −1.06 | −0.68 | −0.66 | −0.12 | −0.55 |

| 3o | 648 | 5.384 | 112 | 2 | 2 | 604 | −0.54 | −1.39 | −0.94 | −0.95 | −0.28 | −0.81 |

| 3p | 680 | 4.601 | 130 | 2 | 2 | 622 | −0.74 | −1.68 | −1.21 | −1.23 | −0.41 | −1.04 |

| Curcumin | 368 | 2.303 | 93 | 2 | 0 | 332 | −0.06 | −0.20 | −0.26 | 0.12 | −0.14 | −0.08 |

GPCRL: GPCR ligand; ICM: ion channel modulator; KI: kinase inhibitor; NRL: nuclear receptor ligand; PI: protease inhibitor; EI: enzyme inhibitor.

Theoretical molecular properties, predicted by Osiris software, for new C-5 curcumin analogues (3a–3p) are tabulated in Table 3 which include toxicity risks (mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, irritation, and reproduction) and physicochemical properties (m i log P, solubility, drug likeness, and drug score) of compounds (3a–3p). Toxicity risk alerts give probability of harmful risks under specified category. From data in Table 3 it is clear that most of the molecules are supposed to be nonmutagenic, nonirritating with no reproductive effects. The drug score is sum of various parameters such as drug likeness, m i Log P, log S, molecular weight, and toxicity risks in the form of single valued figure that may be used to judge the compounds overall capability to qualify requirements for a drug. It was found that most of the compounds (3a–3p) have properties comparable to that of the standard compound curcumin.

Table 3.

Osiris calculations of new curcumin analogues (3a–3p).

| Compound | Prediction of toxicity risk | Molecular properties calculations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUT | TUMO | IRRI | REP | M.W. | ClogP | logS | D-L | D-S | |

| 3a | G | G | G | G | 532 | 5.04 | −6.57 | 2.13 | 0.29 |

| 3b | G | G | G | G | 600 | 6.26 | −8.04 | 3.80 | 0.19 |

| 3c | G | G | G | G | 600 | 6.26 | −8.04 | 4.59 | 0.20 |

| 3d | G | G | G | G | 688 | 6.43 | −8.24 | 1.80 | 0.16 |

| 3e | G | G | G | G | 568 | 5.15 | −7.20 | 2.53 | 0.25 |

| 3f | G | G | G | G | 588 | 6.30 | −7.95 | 5.78 | 0.20 |

| 3g | Y | Y | G | G | 622 | 4.78 | −7.49 | −1.47 | 0.09 |

| 3h | G | G | G | G | 592 | 4.83 | −6.61 | 3.27 | 0.28 |

| 3i | Y | Y | G | G | 682 | 4.57 | −7.53 | −0.33 | 0.11 |

| 3j | G | G | G | G | 648 | 6.09 | −7.98 | 6.77 | 0.19 |

| 3k | G | G | G | G | 660 | 6.05 | −8.08 | 5.70 | 0.18 |

| 3l | G | G | G | G | 560 | 4.61 | −6.20 | 3.91 | 0.32 |

| 3m | G | G | G | G | 588 | 5.24 | −6.89 | 2.97 | 0.25 |

| 3n | G | G | G | G | 620 | 4.40 | −6.24 | 4.60 | 0.33 |

| 3o | G | G | G | G | 480 | 5.03 | −6.93 | 4.18 | 0.24 |

| 3p | G | G | G | G | 680 | 4.19 | −6.27 | 5.88 | 0.28 |

| Curcumin | G | G | G | G | 368 | 2.97 | −3.62 | −3.95 | 0.39 |

G = no toxicity risk; Y = low toxicity risk; R = high toxicity risk; MUT: mutagenic; TUMO: tumorigenic; IRRI: irritant; REP: reproductive effective; Mol. Wt.: molecular weight in g/mol; ClogP: log of octanol/water partition coefficient; S: solubility; D-L: drug likeness; D-S: drug score.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

All chemicals used in synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Himedia. Thin layer chromatography (Merck TLC silica gel 60 F254) was used to monitor the progress of reactions. The compounds were purified when needed by silica gel column (60–120 meshes). Melting points were determined on EZ-Melt automated melting point apparatus, Stanford Research systems, and are uncorrected. IR (chloroform/film) spectra were recorded using Perkin-Elmer FT-IR spectrophotometer and values are expressed as υ max cm−1. Mass spectra were recorded in waters micromass LCT Mass Spectrometer. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Jeol ECX spectrospin at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively, in deuterated solvents with TMS as an internal standard. Chemical shift values are recorded on δ ppm and the coupling constants J are in Hz.

3.2. General Procedure for Synthesis of N-Phenyl and N-Benzyl Acetamides (1a–1j)

To a stirred solution of respective aromatic amine derivatives/benzyl amine derivatives (10 mmol) in dichloromethane, 30 mmol of K2CO3 was added. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0°C and chloroacetyl chloride (11 mmol) was added slowly drop wise. After addition of chloroacetyl chloride reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 3 hours. After completion of reaction solvent was evaporated with rota evaporator and residue obtained was filtered and washed thoroughly with water. The product obtained (1a–1j) was pure enough to be used as such in subsequent steps.

3.3. General Procedure for Synthesis of C-5 Curcumin Analogues (2a–2b)

To a stirred solution of acetone (30 mmol) in 1 : 1 acetic acid/HCl p-hydroxybenzaldehyde/vanillin (63 mmol) was added, respectively. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 16–18 hours at room temperature. After completion of reaction, the product was precipitated by addition of water to reaction mixture. The precipitate obtained was filtered, washed with water, and recrystallized from ethanol to get pure compound (2a, 2b) in good yield.

3.4. General Procedure for Synthesis of New C-5 Curcumin Analogues (3a–3p)

To a stirred solution of C-5 curcumin analogue (2a/2b) (0.84 mmol) in acetone, 0.25 mmol of KI and 2.52 mmol of K2CO3 were added. Further, 1.7 mmol of respective amide (1a–1j) was added to reaction mixture and it was allowed to stir at room temperature for 10–12 hours. After completion of reaction, monitored by TLC, the solvent was evaporated and residue obtained was filtered and washed with water. The crude product obtained was purified by column chromatography using ethyl acetate/hexane as eluent to get desired compounds in good yield (3a–3p).

3.4.1. 2, 2′-(((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy)bis(N-zhenylacetamide) 3a

Yield 80% (yellow solid); m.p. 193–195°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3377, 3058, 2914, 1679, 1649, 1599, 1534, 1507, 1442, 1328, 1248, 1173, 1098, 1058, 984, 837, and 755; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 4.77 (s, 4H), 7.06 (t, 3H, J = 3.7 Hz), 7.08 (d, 3H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.19 (d, 1H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.29 (d, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.32 (d, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.42 (d, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.54 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.62 (d, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.71 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.75 (d, 3H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 10.11 (brs, 2H); TOF-MS m/z: 533.1998 (M + 1), calculated for C33H28N2O5: 532.1878.

3.4.2. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(3-chlorophenyl)acetamide) 3b

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 206–208°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3400, 2914, 1678, 1651, 1593, 1508, 1423, 1244, 1173, 1071, 996, 830, and 772; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 4.78 (s, 4H), 7.06 (d, 4H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.12 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.33 (t, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.37–7.46 (m, 1H), 7.53 (t, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.69 (d, 1H, J = 16.8 Hz), 7.74 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 7.82 (s, 2H); TOF-MS m/z: 601.1219 (M + 1), calculated for C33H26Cl2N2O5: 600.1345.

3.4.3. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-chlorophenyl)acetamide) 3c

Yield 85% (light yellow solid); m.p. 219–221°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3330, 2929, 1672, 1643, 1599, 1508, 1400, 1249, 1170, 1093, 1009, 974, 833, and 702; 1H NMR (δ 6-DMSO, 400 MHz): δ 4.77 (s, 4H), 7.07 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.20 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.35 (d, 2H, J = 5.1 Hz), 7.38 (d, 2H, J = 5.1 Hz), 7.44–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.65 (d, 2H, J = 5.1 Hz), 7.67 (d, 2H, J = 2.9 Hz), 7.68 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 7.75 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 601.1219 (M+1), calculated for C33H26Cl2N2O5: 600.1345.

3.4.4. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-bromophenyl)acetamide) 3d

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 210–212°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3385, 2927, 1689, 1644, 1602, 15.08, 1397, 1244, 1172, 1065, 1008, 831, and 703; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6,400 MHz): δ 4.77 (s, 4H), 7.06 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.48 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.60 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.71 (d, 2H, J = 16.5 Hz), and 7.74 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 689.0208 (M + 1), calculated for C33H26Br2N2O5: 688.0355.

3.4.5. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-fluorophenyl)acetamide) 3e

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 263-264°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3385, 3043, 2916, 1678, 1647, 1602, 1585, 1536, 1508, 1411, 1340, 1247, 1173, 1098, 1059, 984, 834, and 733; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.77 (s, 4H), 7.08 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.15 (d, 1H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.16 (d, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.18 (d, 1H, J = 5.9 Hz), 7.22 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.65 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 2.2 Hz, J 2 = 2.9 Hz), 7.66 (d, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.67 (d, 1H, J = 6.2 Hz), 7.72 (d, 1H, J = 16.1 Hz), and 7.76 (d, 5H, J = 8.8 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 569.1810 (M + 1), calculated for C33H26F2N2O5: 568.1648.

3.4.6. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)acetamide) 3f

Yield 81% (yellow solid); m.p. 225–227°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3404, 2924, 1674, 1622, 1601, 1509, 1422, 1226, 1172, 1098, 980, 826, 764, and 703; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 2.11 (s, 12H), 4.81 (s, 4H), 7.07 (d, 6H, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.11 (d, 4H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.74 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), and 7.78 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 589.2624 (M + 1), calculated for C37H36N2O5: 588.2354.

3.4.7. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(3-nitrophenyl)acetamide) 3g

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 185–187°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3380, 3122, 2913, 1703, 1648, 1600, 1527, 1508, 1425, 1350, 1242, 1173, 1069, 974, and 830; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 4.82 (s, 4H), 7.08 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.60 (t, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.72 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.75 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.91 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 2.2 Hz, J 2 = 6.6 Hz), 7.98 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), and 8.66 (t, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 623.1700 (M + 1), calculated for C33H26N4O9: 622.1546.

3.4.8. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-phenylacetamide) 3h

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 208–210°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3371, 2937, 1693, 1644, 1617, 1593, 1509, 1485, 1422, 1309, 1261, 1189, 1093, 1034, 978, 826, and 720; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 4.01 (s, 6H), 4.69 (s, 4H), 6.97 (d, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz), 7.00 (d, 2H, J = 1.5 Hz), 7.15 (d, 1H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.17 (s, 1H), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 1.5 Hz), 7.24 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 1.5, J 2 = 6.6 Hz), 7.35 (d, 3H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, 4H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.69 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), and 8.75 (brs, 2H); TOF-MS m/z: 593.2210 (M + 1), calculated for C35H32N2O7: 592.2340.

3.4.9. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(3-nitrophenyl)acetamide) 3i

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 173–175°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3381, 3102, 2930, 1693, 1657, 1597, 1531, 1425, 1350, 1256, 1140, 1100, 1030, 981, 803, and 737; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 3.88 (s, 6H), 4.82 (s, 4H), 7.00 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.30 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 1.5 Hz, J 2 = 6.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.61 (d, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.65-7.66 (m, 2H), 7.71 (d, 1H, J = 5.9 Hz), 7.75 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.95 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.64 (brs, 2H), and 10.67 (s, 2H); TOF-MS m/z: 683.1911 (M + 1), calculated for C35H30N4O11: 682.1877.

3.4.10. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)acetamide) 3j

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 216-217°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3390, 3246, 3019, 2921, 1669, 1618, 1589, 1510, 1469, 1338, 1253, 1142, 1098, 1033, 982, 852, and 771; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 2.13 (s, 12H), 3.87 (s, 6H), 4.80 (s, 4H), 7.04 (d, 8H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.25 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.33 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 2.2 Hz, J 2 = 6.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.70 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), and 9.42 (brs, 2H); TOF-MS m/z: 649.2836 (M + 1), calculated for C39H40N2O7: 648.2734.

3.4.11. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-chlorophenyl)acetamide) 3k

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 117–119°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3371, 2937, 1693, 1644, 1593, 1509, 1465, 1261, 1142, 1093, 1034, 978, 826, and 720; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 3.87 (s, 6H), 4.67 (s, 4H), 6.98 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.37 (d, 5H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.44 (s, 3H), 7.64 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 7.68 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 661.1430 (M + 1), calculated for C35H30Cl2N2O7: 660.1375.

3.4.12. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis (4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-benzylacetamide) 3l

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 278-279°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3371, 3281, 2919, 1671, 1655, 1585, 1509, 1423, 1317, 1232, 1175, 1058, 988, 831, and 750; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 4.34 (d, 4H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.62 (s, 2H), 7.04 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.19 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.22 (d, 4H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.23 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 7.28 (d, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.30 (d, 1H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.72 (d, 2H, J = 15.4 Hz), 7.74 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 8.68 (t, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 561.2311 (M + 1), calculated for C35H32N2O5: 560.2456.

3.4.13. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene)) bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-methylbenzyl)acetamide) 3m

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 218–220°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3326, 3047, 2915, 2839, 1658, 1593, 1538, 1511, 1423, 1335, 1293, 1250, 1175, 1062, 1031, 982, 832, and 753; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 2.25 (s, 6H), 4.28 (d, 4H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.60 (s, 4H), 7.03 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.09 (d, 4H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.12 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.72 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.74 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 8.62 (t, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 589.2624 (M + 1), calculated for C37H36N2O5: 588.2658.

3.4.14. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-methoxybenzyl)acetamide) 3n

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 255–257°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3326, 3037, 2915, 2839, 1658, 1598, 1538, 1511, 1423, 1335, 1293, 1250, 1176, 1113, 1062, 1031, 982, 832, and 753; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 3.70 (s, 6H), 4.26 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 4.59 (s, 4H), 6.85 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.03 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.16 (d, 4H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.19 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.71 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.73 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), and 8.60 (t, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d 6, 100 MHz): δ 41.29, 55.02, 66.97, 113.63, 115.24, 123.85, 127.99, 128.62, 130.21, 131.19, 142.10, 158.21, 159.57, 167.26, and 188.21; TOF-MS m/z: 621.2523 (M + 1), calculated for C37H36N2O7: 620.2453.

3.4.15. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-Oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-methylbenzyl)acetamide) 3o

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 209–211°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3332, 3268, 3074, 2922, 2837, 1662, 1592, 1547, 1510, 1465, 1310, 1256, 1196, 1166, 1138, 1032, 978, 852, 801, 762; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.33 (s, 6H), 3.78 (s, 6H), 4.49 (d, 4H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.62 (s, 4H), 6.92 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 6.96 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.10 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.14 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.15 (d, 5H, J = 3.7 Hz), 7.18 (d, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz), 7.21 (d, 3H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.67 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz); TOF-MS m/z: 649.2836 (M + 1), calculated for C39H40N2O7: 648.2759.

3.4.16. 2, 2′-((((1E,4E)-3-oxopenta-1,4-diene-1,5-diyl)bis(2-methoxy-4,1-phenylene))bis(oxy))bis(N-(4-methoxybenzyl) acetamide) 3p

Yield 87% (yellow solid); m.p. 167–169°C; IR (KBr film) υ max cm−1: 3417, 3286, 3051, 2931, 2835, 1655, 1586, 1512, 1464, 1305, 1248, 1185, 1145, 1031, 972, 841, 080, and 768; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6, 400 MHz): δ 3.71 (s, 6H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 4.26 (d, 4H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.59 (s, 4H), 6.86 (d, 5H, J = 8.1 Hz), 6.96 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.17 (d, 5H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.24 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), 7.29 (dd, 2H, J 1 = 1.5 Hz, J 2 = 6.6 Hz), 7.69 (d, 2H, J = 16.1 Hz), and 8.40 (t, 2H, J = 5.9 Hz); 13C NMR (DMSO-d 6, 100 MHz): δ 41.39, 55.05, 55.73, 68.02, 111.12, 113.66, 113.92, 122.79, 124, 128.59, 128.68, 131.07, 142.46, 149.52, 158.26, 167.38, and 188.11; TOF-MS m/z: 681.2734 (M + 1), calculated for C39H40N2O9: 680.2652.

3.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

KBM5 and HCT116 were used for anticancer assay. The cytotoxic effect of C-5 curcumin analogues was determined by MTT assay [34]. Briefly, HCT116 and KBM5 cells (5 × 104 cells/mL) were treated with 5 μM of indicated test sample in a final volume of 0.1 mL at 37°C for 72 h. Thereafter, 1 mg/mL of MTT solution was added to the untreated/treated cells. After 2 h incubation at 37°C, 0.1 mL of the cell lysis buffer (20% SDS; 50% dimethylformamide; pH 4.7) was added. After an overnight incubation at 37°C, the OD at 590 nm were measured using a 96-well multiscanner autoreader (Dynatech MR 5000, Chantilly, VA), with the extraction buffer as a blank and reduction in viability as per treatment was calculated by comparing with untreated cells as control.

3.6. Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Potential: Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

To determine the anti-inflammatory potential of curcumin analogues, downmodulation in NF-κB activation was measured in untreated and treated KBM5 cells. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed with nuclear extract of treated-, untreated-, and induced-cells as described previously [35]. In brief, nuclear extracts prepared from cancer cells were incubated with 32P end-labeled 45-mer double-stranded NF-κB oligonucleotide (15 μg of protein with 16 fmol of DNA) from the HIV long terminal repeat (5′-TTGTTACAAGGGACTTTC CGCTG GGGACTTTC CAGGGA GGCGT GG-3′, with NF-κB-binding sites) for 30 min at 37°C. The resulting protein-DNA complex was separated from free oligonucleotides on 6.6% polyacrylamide gels. The dried gels were visualized by Phosphor-Imager imaging device (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), and radioactive bands were quantified using Image Quant software.

4. Conclusion

These new curcumin analogues exhibited good potential to inhibit TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation so they can be further optimised to get lead molecule with good anti-inflammatory activity. Some of these compounds also exhibited potent cytotoxicity against KBM5 and HCT116 cancer cell lines so further modifications of these molecules could be done to get a lead molecule for further studies.

Acknowledgments

Amit Anthwal and Bandana K. Thakur are thankful to UGC for research fellowship. M. S. M. Rawat thanks University Grants Commission (F4-10/2010 (BSR) dated March 7, 2012), New Delhi, India, for financial support.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Cragg GM, Newman DJ, Snader KM. Natural products in drug discovery and development. Journal of Natural Products. 1997;60:52–60. doi: 10.1021/np9604893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao DS, Sekhara NC, Satyanarayana MN, Srinivasan M. Effect of curcumin on serum and liver cholesterol levels in the rat. Journal of Nutrition. 1970;100(11):1307–1315. doi: 10.1093/jn/100.11.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patil TN, Srinivasan M. Hypocholesteremic effect of curcumin in induced hypercholesteremic rats. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1971;9(2):167–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keshavarz K. The influence of turmeric and curcumin on cholesterol concentration of eggs and tissues. Poultry Science. 1976;55(3):1077–1083. doi: 10.3382/ps.0551077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soudamini KK, Unnikrishnan MC, Soni KB, Kuttan R. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation and cholesterol levels in mice by curcumin. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1992;36:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soni KB, Kuttan R. Effect of oral curcumin administration on serum peroxides and cholesterol levels in human volunteers. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1992;36(4):273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain MS, Chandrasekhara N. Effect of curcumin on cholesterol gallstone induction in mice. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1992;96:p. 288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asai A, Miyazawa T. Dietary curcuminoids prevent high-fat diet-induced lipid accumulation in rat liver and epididymal adipose tissue. The Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(11):2932–2935. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramírez-Tortosaemail MC, Mesa MD, Aguilera MC, et al. Oral administration of a turmeric extract inhibits LDL oxidation and has hypocholesterolemic effects in rabbits with experimental atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1999;147(2):371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naidu KA, Thippeswamy NB. Inhibition of human low density lipoprotein oxidation by active principles from spices. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2002;229(1-2):19–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1017930708099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patro BS, Rele S, Chintalwar GJ, Chattopadhyay S, Adhikari S, Mukherjee T. Protective activities of some phenolic 1,3-diketones against lipid peroxidation: possible involvement of the 1,3-diketone moiety. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:p. 364. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020402)3:4<364::AID-CBIC364>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava R, Puri V, Srimal RC, Dhawan BN. Effect of curcumin on platelet aggregation and vascular prostacyclin synthesis. Arzneimittelforschung. 1986;36:715–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anand P, Sundaram C, Jhurani S, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin and cancer: an “old-age” disease with an, age-old , solution. Cancer letters. 2008;267(1):133–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kunnumakkara AB, Anand P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of different cancers through interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins. Cancer Letters. 2008;269(2):199–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal BB, Kunnumakkara AB, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Sung B, Anand P. Potential of spice-derived phytochemicals for cancer prevention. Planta Medica. 2008;74:p. 1560. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal BB, Kumar A, Bharti AC. Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Research. 2003;23(1):363–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008;75(4):787–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang G, Li X, Chen L, et al. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activities of monocarbonyl analogues of curcumin. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(4):1525–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad S, Tyagi AK, Aggarwal BB. Recent developments in delivery, bioavailability, absorption and metabolism of curcumin: the golden pigment from golden spice. Cancer Research Treatment. 2014;46(1):2–18. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.46.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan MH, Huang TM, Lin JK. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metabolism & Disposition. 1999;27:486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ireson CR, Jones DJ, Orr S, et al. Metabolism of the cancer chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat intestine. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11(1):105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer E, Hoehle SI, Walch SG, Riess A, Solyom AM, Metzler M. Curcuminoids form reactive glucuronides in vitro . Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55:538–544. doi: 10.1021/jf0623283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson TP, Ehlers T, Hubbard RB, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of angiogenesis inhibitors: aromatic enone and dienone analogues of curcumin. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2003;13(1):115–117. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohtsu H, Xiao Z, Ishida J, Nagai M, Wang HK, Itokawa H. Antitumor agents. 217. Curcumin analogues as novel androgen receptor antagonists with potential as anti-prostate cancer agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;45:5037–5042. doi: 10.1021/jm020200g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang G, Shao L, Wang Y, et al. Exploration and synthesis of curcumin analogues with improved structural stability both in vitro and in vivo as cytotoxic agents. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;17:2623–2631. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamakoshi H, Ohori H, Kudo C, et al. Structureactivity relationship of C5-curcuminoids and synthesis of their molecular probes thereof. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;18(3):1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anthwal A, Rajesh UC, Rawat MSM, et al. Novel metronidazole-chalcone conjugates with potential to counter drug resistance in Trichomonas vaginalis . European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;79:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parvez A, Meshram J, Tiwari V, et al. Pharmacophores modeling in terms of prediction of theoretical physico-chemical properties and verifcation by experimental correlations of novel coumarin derivatives produced via Betti’s protocol. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;45(9):4370–4378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parvez A, Jyotsna M, Taibi BH. Theoretical prediction and experimental verification of antibacterial potential of some monocyclic β-lactams containing two synergetic buried antibacterial pharmacophore sites. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon and the Related Elements. 2010;185:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30. http://www.molinspiration.com/

- 31. http://www.osiris.com.

- 32.Chang LCW, Spanjersberg RF, Beukers MW, Ijzerman AP. 2,4,6-Trisubstituted pyrimidines as a new class of selective adenosine A-1 receptor antagonists. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;47:6529–6540. doi: 10.1021/jm049448r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark DE. Rapid calculation of polar molecular surface area and its application to the prediction of transport phenomena. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1999;88(8):807–814. doi: 10.1021/js9804011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haridas V, Darnay BG, Natarajan K, Heller R, Aggarwal BB. Overexpression of the p80 TNF receptor leads to TNF-dependent apoptosis, nuclear factor-kappa B activation, and c-Jun kinase activation. The Journal of Immunology. 1998;160:p. 3152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaturvedi MM, Mukhopadhyay A, Aggarwal BB. Assay for redox-sensitive transcription factor. Methods in Enzymology. 2000;319:585–602. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)19055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]