Abstract

Background

A number of clinical and experimental studies have investigated the effect of atorvastatin on atrial fibrillation (AF), but the results are equivocal. This meta-analysis was performed to evaluate whether atorvastatin can reduce the risk of AF in different populations.

Methods

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database for all published studies that examined the effect of atorvastatin therapy on AF up to April 2014. A random effects model was used when there was substantial heterogeneity and a fixed effects model when there was negligible heterogeneity.

Results

Eighteen published studies including 9952 patients with sinus rhythm were identified for inclusion in the analysis. Ten studies investigated primary prevention of AF by atorvastatin in patients without AF, seven studies investigated secondary prevention of atorvastatin in patients with AF, and one study investigated mixed populations of patients. Overall, atorvastatin was associated with a decreased risk of AF (odds ratio (OR) 0.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.36–0.70, P < 0.0001). However, subgroup analyses showed that in the primary prevention subgroup (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.38–0.81, P = 0.002), atorvastatin reduced the risk of new-onset AF in patients after coronary surgery (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.68, P = 0.0002), but had no beneficial effect in patients without coronary surgery (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.59–1.58, P = 0.89); in the secondary prevention subgroup, atorvastatin had no beneficial effect on AF recurrence in patients with electrical cardioversion (EC) (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.25–1.32, P = 0.19) or without EC (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.14–1.06, P = 0.06).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests that atorvastatin has an overall protective effect against AF. However, this preventive effect was not seen in all types of AF. Atorvastatin was significantly associated with a decreased risk of new-onset AF in patients after coronary surgery. Moreover, atorvastatin did not prove to exert a significant protective effect against the AF recurrences in both patients who had experienced sinus rhythm restoration by means of EC and those who had obtained cardioversion by means of drug therapy. Thus, further prospective studies are warranted.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Atorvastatin, Meta-analysis

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in clinical practice and is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality [1,2]. However, the mechanism of AF remains incompletely understood and treatment is not satisfactory. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have suggested that inflammation and oxidative stress contribute to atrial remodeling and play an important role in AF development [2-4]. It has been suggested that statin medications may be beneficial in protecting against AF, because of their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [5]. Recent meta-analyses [6,7] of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that statin therapy was significantly associated with a decreased risk of AF in different patient populations. Atorvastatin is a highly effective statin medication and is widely used clinically. It is the most studied statin in relation to AF [6,7], but the results are equivocal. We therefore performed this meta-analysis to evaluate whether atorvastatin can reduce the risk of AF in different populations.

Methods

Literature search and inclusion criteria

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database for all published studies that examined the effect of atorvastatin therapy on AF up to April 2014. We conducted text searches with the search terms “atorvastatin” and “atrial fibrillation”. We also manually searched references from selected clinical trials, recent meta-analyses and review articles.

We included studies that met the following specified criteria: (1) comparison of atorvastatin with placebo or control treatment, regardless of the background therapy; (2) randomized controlled human trials; (3) new-onset AF or recurrent AF in each group as an outcome.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted the following information from each study: (1) study population sample size and characteristics; (2) dose and duration of treatment; (3) outcome measures. One reviewer abstracted the data, and then the other checked the documentation. They finally reached an agreement on the data by consensus. We used the Jadad score [8] to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical calculations with RevMan version 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We allocated the results of each study as dichotomous frequency data to evaluate the effect of atorvastatin on new-onset AF or recurrence of AF. We calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for new-onset or recurrent AF in each trial separately, and for combinations of studies according to fixed-effect and random-effect models. We used the chi-squared test to assess heterogeneity and I2 to quantify heterogeneity. If the chi-squared test P-value was > 0.10 and I2 was < 50%, we analyzed the data using a fixed-effect model (the Mantel–Haenszel method), otherwise we used a random-effect model [9,10]. If the heterogeneity was significant, we attempted to explain the differences based on the patient clinical characteristics of the included studies. The P-value threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05 for the effect sizes. We also used Begg and Egger tests [11,12] to assess the presence of publication bias.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

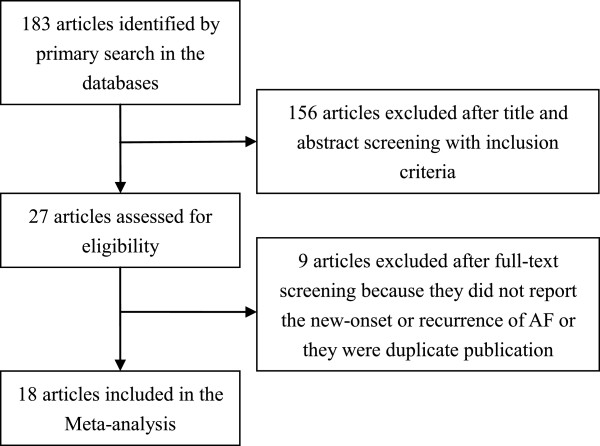

Eighteen published studies [13-30] including 9952 patients with sinus rhythm were identified for inclusion in the analysis. The process of study selection is summarized in Figure 1. These studies compared the use of atorvastatin vs. no statins on AF in various populations. Ten studies [15,17-19,21-24,26,28] investigated the use of atorvastatin in primary prevention of AF in patients after cardiac surgery (n = 8) [15,17,19,21-24,28] or implantation of a pacemaker (n = 1) [18], or in patients with a prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (n = 1) [26]. Seven studies [14,16,20,25,27,29,30] investigated the use of atorvastatin in secondary prevention of AF in patients who received electrical cardioversion (EC; n = 4) [16,20,25,27], catheter ablation (n = 2) [29,30] or pharmacological treatment (n = 1) [14]. The MIRACL trial [13] included both AF and non-AF patients, so MIRACL-1 and MIRACL-2 were used to represent the primary and secondary prevention subgroups. These studies were published between 2004 and 2013 and the sample sizes ranged from 40 to 4731. Intervention strategies of atorvastatin and documentation of AF were also variable. The studies received Jadad scores of 2 (n = 5) [16,18,21,27,30], 3 (n = 3) [14,19,24], 4 (n = 3) [15,23,29], or 5 (n = 7) [13,17,20,22,25,26,28] points. The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of the study selection and exclusion process. AF: atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study, year | n | Population | Dosage | Duration | Endpoint | Documentation of AF | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIRACL 2004 [13] |

3087 |

Acute coronary syndrome |

80 mg/d |

16 weeks |

New onset or recurrence of AF |

Follow-up with ECG |

5 |

| Dernellis et al. 2005 [14] |

80 |

Paroxysmal AF |

20–40 mg/d |

4–6 months |

Recurrence of AF |

48-h ambulatory ECG monitoring |

3 |

| Chello et al. 2006 [15] |

40 |

Coronary bypass surgery |

20 mg/d |

3 weeks |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring |

4 |

| Ozaydin et al. 2006 [16] |

48 |

Persistent AF and scheduled EC |

10 mg/d |

3 months |

Recurrence of AF |

24-h ambulatory ECG monitoring |

2 |

| ARMYDA-3 2006 [17] |

200 |

Cardiac surgery |

40 mg/d |

30 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring after the operation, then follow-up with ECG |

5 |

| Tsai et al. 2008 [18] |

106 |

Bradyarrhythmia and implantation of pacemaker |

20 mg/d |

1 year |

AF/AHE ≥ 10 min |

Pacemaker interrogation |

2 |

| Song et al. 2008 [19] |

124 |

Off-pump coronary bypass surgery |

20 mg/d |

30 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring after the operation, then follow-up with ECG |

3 |

| Almroth et al. 2009 [20] |

234 |

Persistent AF and scheduled EC |

80 mg/d |

30 days |

Recurrence of AF |

Follow-up with ECG |

5 |

| Melina et al. 2009 [21] |

632 |

Coronary bypass surgery |

40 mg/d |

Not mentioned |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

Not mentioned |

2 |

| Ji et al. 2009 [22] |

140 |

Off-pump coronary bypass surgery |

20 mg/d |

13 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring or 12-lead ECG |

5 |

| Spadaccio et al. 2010 [23] |

50 |

Coronary bypass surgery |

20 mg/d |

7 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring |

4 |

| Sun et al. 2011 [24] |

100 |

Coronary bypass surgery |

20 mg/d |

14 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring |

3 |

| SToP AF 2011 [25] |

64 |

Persistent AF and scheduled EC |

80 mg/d |

12 months |

Recurrence of AF |

Follow-up with ECG and 24-h ambulatory ECG monitoring |

5 |

| SPARCL 2011 [26] |

4731 |

Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack |

80 mg/d |

4.8 years |

New-onset AF |

Follow-up with ECG |

5 |

| Demir et al. 2011 [27] |

48 |

Persistent AF and scheduled EC |

40 mg/d |

2 months |

Recurrence of AF |

Weekly follow-up with ECG |

2 |

| Baran et al. 2012 [28] |

60 |

Coronary bypass surgery |

40 mg/d |

30 days |

New-onset AF after cardiac surgery |

ECG monitoring after the operation, then follow-up with ECG |

5 |

| Suleiman et al. 2012 [29] |

125 |

AF undergoing catheter ablation |

80 mg/d |

3 months |

Recurrence of AF |

Follow-up with ECG and 72-h ambulatory ECG monitoring |

4 |

| Jiang et al. 2013 [30] | 101 | AF undergoing catheter ablation | 40 mg/d | 6 months | Recurrence of AF | Not mentioned | 2 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AHE: Atrial high rate episode; ARMYDA-3: Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Dysrhythmia After cardiac surgery study; EC: Electrical cardioversion; ECG: Electrocardiogram; MIRACL: Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering study; SPARCL: Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels; SToP AF: statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial.

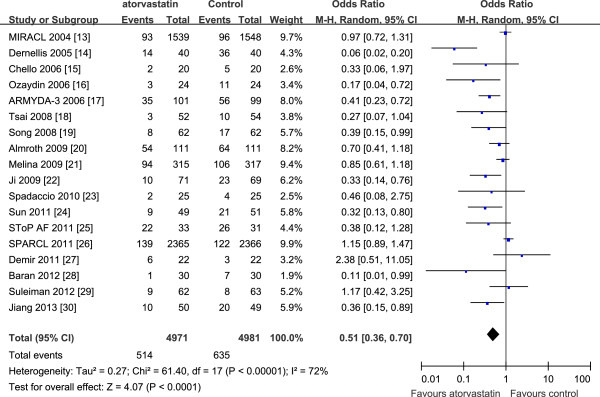

Results of the meta-analysis

The meta-analysis of all included studies indicated that atorvastatin was effective for the prevention of AF (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.36–0.70, P < 0.0001), but there was substantial heterogeneity (P < 0.00001, I2 = 72%). The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effect of atorvastatin on atrial fibrillation. ARMYDA-3: atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial dysrhythmia after cardiac surgery study; CI: confidence interval; MIRACL: myocardial ischemia reduction with aggressive cholesterol lowering study; SPARCL: Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels; SToP AF: statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial.

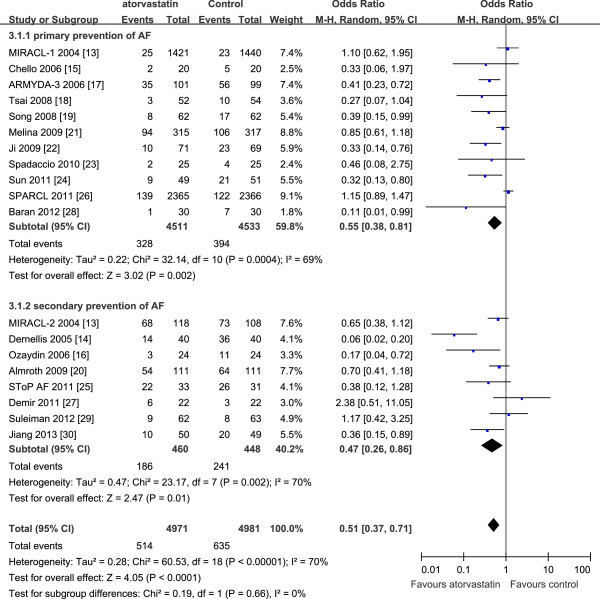

Subgroup analysis

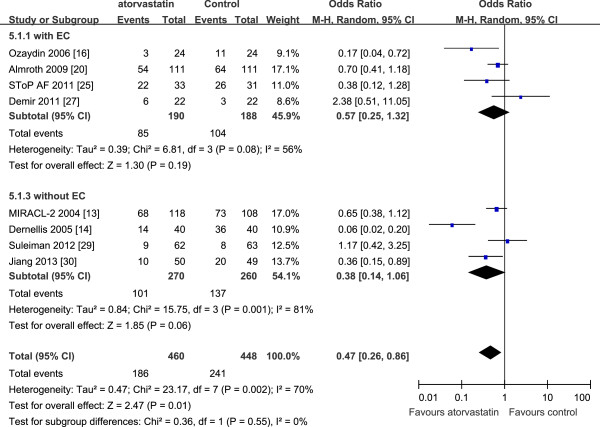

A subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of atorvastatin on primary and secondary prevention of AF. The results showed that atorvastatin was effective for both primary prevention (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.38–0.81, P = 0.002) and secondary prevention (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.26–0.86, P = 0.01) of AF. However, the heterogeneity remained substantial (primary prevention: P = 0.0004, I2 = 69%; secondary prevention: P = 0.002, I2 = 70%) in both groups. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Primary and secondary prevention of AF with atorvastatin. AF: atrial fibrillation; ARMYDA-3: atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial dysrhythmia after cardiac surgery study; CI: confidence interval; MIRACL: myocardial ischemia reduction with aggressive cholesterol lowering study; SPARCL: Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels; SToP AF: statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial.

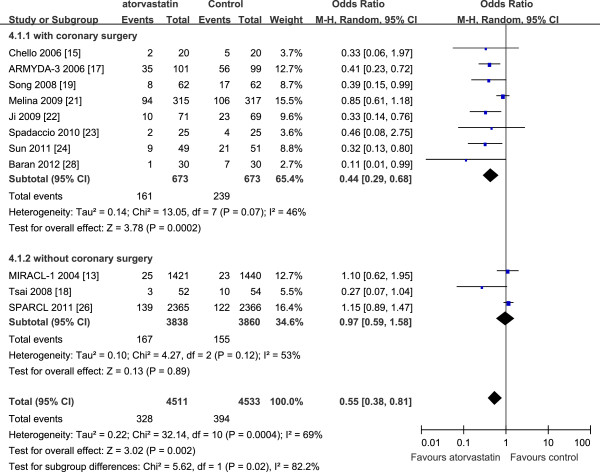

Eleven trials [15,17-19,21-24,26,28] that investigated the use of atorvastatin in primary prevention of AF were divided into two subgroups on the basis of whether patients underwent coronary surgery. The results of subgroup analysis showed that atorvastatin was effective in reducing the risk of AF in patients after coronary surgery (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.68, P = 0.0002), although there was heterogeneity (P = 0.07, I2 = 46%), but showed no beneficial effect in patients without coronary surgery (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.59–1.58, P = 0.89), again showing heterogeneity (P = 0.12, I2 = 53%). The results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Primary prevention of AF with atorvastatin in patients with or without coronary surgery. AF: atrial fibrillation; ARMYDA-3: atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial dysrhythmia after cardiac surgery study; CI: confidence interval; MIRACL: myocardial ischemia reduction with aggressive cholesterol lowering study; SPARCL: Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels.

Eight trials [14,16,20,25,27,29,30] that investigated the use of atorvastatin in secondary prevention of AF were divided into two subgroups on the basis of whether patients underwent EC. The results of subgroup analysis showed that atorvastatin had no beneficial effect either in patients with EC (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.25–1.32, P = 0.19) or without EC (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.14–1.06, P = 0.06). The heterogeneity remained substantial (with EC: P = 0.08, I2 = 56%; without EC: P = 0.001, I2 = 81%) in both groups. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Secondary prevention of AF with atorvastatin in patients with or without EC. AF: atrial fibrillation; CI: confidence interval; EC: electrical cardioversion; MIRACL: myocardial ischemia reduction with aggressive cholesterol lowering study; SToP AF: statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

The results were similar when studies with Jadad score < 3 [16,18,21,27,30] were removed from the analysis (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.32–0.73; P = 0.0004). These studies were also excluded when performing the subgroup analyses and no obvious change in effect size was detected. However, there was little heterogeneity in the coronary surgery subgroup (P = 0.96, I2 = 41%), so a fixed-effect model was used to analyze the data. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis

| |

Number of trials |

Effect size, odds ratio (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | After excluding 5 trials # | Total | After excluding 5 trials # |

| Overall |

18 |

13 |

0.51 (0.36 to 0.70) |

0.49 (0.32 to 0.73) |

| Primary prevention |

11 |

9 |

0.55 (0.38 to 0.81) |

0.51 (0.31 to 0.84) |

| With coronary surgery |

8 |

7 |

0.44 (0.29 to 0.68) |

0.36 (0.25 to 0.51) |

| Without coronary surgery |

3 |

2 |

0.97 (0.59 to 1.58) |

1.14 (0.91 to 1.43) |

| Secondary prevention |

8 |

5 |

0.47 (0.26 to 0.86) |

0.46 (0.22 to 0.96) |

| With electrical cardioversion |

4 |

2 |

0.57 (0.25 to 1.32) |

0.63 (0.39 to 1.03) |

| Without electrical cardioversion | 4 | 3 | 0.38 (0.14 to 1.06) | 0.38 (0.09 to 1.62) |

CI: confidence interval; #Studies with Jadad score <3 were removed from the analysis.

Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s and Egger’s tests when the subgroup analyses were performed. Publication bias was statistically insignificant in patients with EC (Begg, P = 1.00; Egger, P = 0.81), in patients without EC (Begg, P = 0.73; Egger, P = 0.45), in patients without coronary surgery (Begg, P = 0.30; Egger, P = 0.34), and in patients with coronary surgery when a trial with Jadad score < 3 was excluded [21] (Begg, P = 0.55; Egger, P = 0.18).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that excluded bias caused by different types of statins, and only assessed the efficacy of atorvastatin on the prevention of AF in different populations. The meta-analysis suggested that atorvastatin could protect against AF overall. However, subgroup analysis indicated that this preventive effect was not seen in all types of AF. Atorvastatin was significantly associated with a decreased risk of new-onset AF in patients after coronary surgery, while atorvastatin did not prove to exert a significant protective effect against the AF recurrences in both patients who had experienced sinus rhythm restoration by means of EC and those who had obtained cardioversion by means of drug therapy.

Atorvastatin is widely used in clinical practice, and more clinical studies related to AF have been carried out with atorvastatin than with other statins. In the latest meta-analysis [7], 28 RCTs were included to evaluate the preventive effect of statin therapy on AF. Of the 28 trials, atorvastatin was studied in 16, indicating that atorvastatin has the most evidenced-medicine data on AF. The meta-analysis [7] included all types of statins and suggested that statin therapy reduced AF significantly, with an OR of 0.69 (95% CI 0.57–0.83). The present meta-analysis suggests that atorvastatin is a highly effective statin medication in reducing AF, with an overall OR of 0.51 (95% CI 0.36–0.70). Rosuvastatin is another highly effective statin, but only limited data are available about its potential effect on AF. A previous meta-analysis of rosuvastatin [31] only included four RCTs and showed that it reduced the risk of AF by 30% (relative risk 0.70, 95% CI 0.54–0.91).

The preventive effect of atorvastatin against AF did not appear to be dose-dependent, as the trials that used a high dose of atorvastatin (80 mg/day) [13,20,25,26,29] did not have lower ORs. Trials with different doses of atorvastatin were limited and with significant heterogeneity in the study populations, so subgroup analysis according to different doses was not performed in our meta-analysis. A previous meta-analysis [32] even came to the conclusion that the preventive effect of atorvastatin on AF may be more significant at a lower dose (10–40 mg/day), while a recent study [33] on patients undergoing cardiac surgery suggested that the preventive effect of atorvastatin on postoperative AF was not dose-dependent.

In our meta-analysis, subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of atorvastatin on AF in different populations. Atorvastatin showed less atrial antiarrhythmic properties than expected in different populations, especially in the prevention of AF recurrence. In the primary prevention subgroup, the results showed that atorvastatin was significantly associated with a decreased risk of new-onset AF in patients after coronary surgery (Figure 4), which was in accord with other recent meta-analyses [7,34]. However, atorvastatin did not appear to protect against new-onset AF in patients who did not undergo coronary surgery (Figure 4). However, as only three trials were included in this subgroup and there was significant heterogeneity among them, it is inappropriate to come to the conclusion that atorvastatin was ineffective in this population. A recent meta-analysis [7] included nine RCTs and also found a negative result, which the authors suggested may be attributed to a relatively short follow-up time. In our secondary prevention subgroup, when trials were divided into two groups of patients with or without EC, the results showed that atorvastatin had no beneficial effect on the recurrence of AF in either group (Figure 5). These results contrasted with previous meta-analyses [6,35], which suggested that statin therapy significantly decreased the risk of AF recurrence in patients with or without EC. In our subgroup analysis, because only four trials were included in each subgroup and the study population of each study was relatively small, it is inappropriate to come to the conclusion that atorvastatin is ineffective in the secondary prevention of AF, and further investigation is required.

At present, an increasing amount of evidence suggests that inflammation and oxidative stress may play important roles in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of AF [2,36,37]. The mechanism of action of statins in the treatment of AF is suggested to be related to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [4,38]. The capacity of statins to reduce inflammation is relatively well established. Eight trials [14-17,22,24,25,28] in our meta-analysis proved that atorvastatin could reduce inflammatory biomarkers, especially in patients after cardiac surgery [15,17,22,24,28] when there was obvious acute inflammation. Furthermore, the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) is considered to be a very important cellular source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the human body, while excessive production of ROS is likely involved in the structural and electrical remodeling of the heart, and contributes to atrial fibrosis and AF [39]. Atorvastatin could inhibit ROS generation via downregulation of NOX2, thus protecting against AF [40]. In recent years, myeloperoxidase (MPO), a heme enzyme abundantly expressed by neutrophils, was shown to be a crucial prerequisite for atrial fibrosis and AF [2,41]. Statins could strongly inhibit MPO mRNA expression in human and murine monocyte-macrophages, and consequently reduce MPO protein and enzyme activity [42]. These may be the underlying mechanisms of statin therapy on AF and deserve further investigation.

This meta-analysis indicated that patients who underwent coronary surgery derived more benefit from atorvastatin in the prevention of AF than other populations. The reasons can be summarized as follows. The postoperative course of a coronary surgery is characterized by severe inflammation and oxidative stress resulting from extracorporeal circulation and surgical manipulation of the epicardial coronary vessels. Thus the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of atorvastatin as mentioned above may account for its beneficial effects in these patients. AF after coronary surgery is mainly caused by elevations in atrial pressure, autonomic nervous system imbalance, myocardial ischemic damage and so on [43], thus it can regress over time with surgery recovery. However, non-postoperative AF, especially recurrent AF, is often caused by atrial remodeling such as atrial dilation and fibrosis [44]. This remodeling encompasses changes in electrical, contractile, and structural properties of the atria and may be less responsive to atorvastatin compared with postoperative AF.

This meta-analysis has the following limitations. Only published RCTs were included in our meta-analysis, so publication bias was unavoidable. Although subgroup analyses were performed according to different populations, heterogeneity still existed among the trials, such as sample size, the dose and duration of atorvastatin treatment, and documentation of AF. The trials were limited according to the numbers in some subgroups, so the results were less persuasive.

Conclusions

The meta-analysis suggested that atorvastatin has an overall protective effect against AF. However, subgroup analysis indicated that this preventive effect was not seen in all types of AF. Atorvastatin was significantly associated with a decreased risk of new-onset AF in patients after coronary surgery. Moreover, atorvastatin did not prove to exert a significant protective effect against the AF recurrences in both patients who had experienced sinus rhythm restoration by means of EC and those who had obtained cardioversion by means of drug therapy. Thus, more large-scale prospective RCTs are required to investigate whether atorvastatin is an effective medication for the prevention of AF in different populations.

Abbreviations

AF: Atrial fibrillation; RCTs: Randomized clinical trials; EC: Electrical cardioversion; MIRACL: Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering study; ARMYDA-3: Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Dysrhythmia After cardiac surgery study; SToP AF: Statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial; SPARCL: Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels; NOX: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; MPO: Myeloperoxidase.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

QY conceived the study, participated in the design, collected the data, performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. XY conceived the study, collected the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. YL performed statistical analyses and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Qian Yang, Email: yangqian8411@163.com.

Xiaoyong Qi, Email: hbghxiaoyong_q@126.com.

Yingxiao Li, Email: hbghdgs@163.com.

References

- Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph V, Andrie RP, Rudolph TK, Friedrichs K, Klinke A, Hirsch-Hoffmann B, Schwoerer AP, Lau D, Fu X, Klingel K, Sydow K, Didie M, Seniuk A, von Leitner EC, Szoecs K, Schrickel JW, Treede H, Wenzel U, Lewalter T, Nickenig G, Zimmermann WH, Meinertz T, Boger RH, Reichenspurner H, Freeman BA, Eschenhagen T, Ehmke H, Hazen SL, Willems S, Baldus S. Myeloperoxidase acts as a profibrotic mediator of atrial fibrillation. Nat Med. 2010;16:470–474. doi: 10.1038/nm.2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issac TT, Dokainish H, Lakkis NM. Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll of Cardiol. 2007;50:2021–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho-Gomes AC, Reilly S, Brandes RP, Casadei B. Targeting inflammation and oxidative stress in atrial fibrillation: role of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase inhibition with statins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1268–1285. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam O, Neuberger HR, Bohm M, Laufs U. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 2008;118:1285–1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang WT, Li HJ, Zhang H, Jiang S. The role of statin therapy in the prevention of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:744–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchier L, Clementy N, Babuty D. Statin therapy and atrial fibrillation: systematic review and updated meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013;28:7–18. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835b0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Chaitman B, Goldberger J, Szarek M, Sasiela WJ. Effect of intensive statin treatment on the occurrence of atrial fibrillation after acute coronary syndrome: an analysis of the MIRACL trial. Circulation. 2004;110(Suppl):S740. [Google Scholar]

- Dernellis J, Panaretou M. Effect of C-reactive protein reduction on paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chello M, Patti G, Candura D, Mastrobuoni S, Di Sciascio G, Agro F, Carassiti M, Covino E. Effects of atorvastatin on systemic inflammatory response after coronary bypass surgery. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:660–667. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201407.89977.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaydin M, Varol E, Aslan SM, Kucuktepe Z, Dogan A, Ozturk M, Altinbas A. Effect of atorvastatin on the recurrence rates of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1490–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti G, Chello M, Candura D, Pasceri V, D’Ambrosio A, Covino E, Di Sciascio G. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: results of the ARMYDA-3 (Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Dysrhythmia After cardiac surgery) study. Circulation. 2006;114:1455–1461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CT, Lai LP, Hwang JJ, Wang YC, Chiang FT, Lin JL. Atorvastatin prevents atrial fibrillation in patients with bradyarrhythmias and implantation of an atrial-based or dual-chamber pacemaker: a prospective randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2008;156:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YB, On YK, Kim JH, Shin DH, Kim JS, Sung J, Lee SH, Kim WS, Lee YT. The effects of atorvastatin on the occurrence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Am Heart J. 2008;156:373 e379-316. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almroth H, Hoglund N, Boman K, Englund A, Jensen S, Kjellman B, Tornvall P, Rosenqvist M. Atorvastatin and persistent atrial fibrillation following cardioversion: a randomized placebo-controlled multicentre study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:827–833. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melina G Angeloni E Di Nucci G Benedetto U Fiorani B Sclafani G Comito C Tonelli E Refice S Sinatra R Preoperative HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing CABG: A prospective randomised trial Eur Heart J 200930Suppl 13218664464 [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Mei Y, Wang X, Sun Y, Feng J, Cai J, Xie S, Chi L. Effect of preoperative atorvastatin therapy on atrial fibrillation following off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Circ J. 2009;73:2244–2249. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaccio C, Pollari F, Casacalenda A, Alfano G, Genovese J, Covino E, Chello M. Atorvastatin increases the number of endothelial progenitor cells after cardiac surgery: a randomized control study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;55:30–38. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181c37d4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Ji Q, Mei Y, Wang X, Feng J, Cai J, Chi L. Role of preoperative atorvastatin administration in protection against postoperative atrial fibrillation following conventional coronary artery bypass grafting. Int Heart J. 2011;52:7–11. doi: 10.1536/ihj.52.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi S, Shukrullah I, Veledar E, Bloom HL, Jones DP, Dudley SC. Statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation trial (SToP AF trial) J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:414–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01925.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GG, Chaitman BR, Goldberger JJ, Messig M. High-dose atorvastatin and risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack: analysis of the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial. Am Heart J. 2011;161:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir K, Can I, Koc F, Vatankulu MA, Ayhan S, Akilli H, Aribas A, Alihanoglu Y, Altunkeser BB. Atorvastatin given prior to electrical cardioversion does not affect the recurrence of atrial fibrillation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation who are on antiarrhythmic therapy. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:464–469. doi: 10.1159/000327674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran C, Durdu S, Dalva K, Zaim C, Dogan A, Ocakoglu G, Gurman G, Arslan O, Akar AR. Effects of preoperative short term use of atorvastatin on endothelial progenitor cells after coronary surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:963–971. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9321-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman M, Koestler C, Lerman A, Lopez-Jimenez F, Herges R, Hodge D, Bradley D, Cha YM, Brady PA, Munger TM, Asirvatham SJ, Packer DL, Friedman PA. Atorvastatin for prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Wang X, Zeng L, Tu S, Zhang Z. Atorvastatin therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation ablation to maintain sinus rhythm. Heart. 2013;99(Suppl 3):A192. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Korantzopoulos P, Li L, Li G. Preventive effects of rosuvastatin on atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:3058–3060. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhang Y, Gao M, Wang J, Wang Q, Wang X, Su L, Hou Y. Statin therapy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1051–1062. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.11.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourliouros A, Valencia O, Hosseini MT, Mayr M, Sarsam M, Camm J, Jahangiri M. Preoperative high-dose atorvastatin for prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn EW, Liakopoulos OJ, Stange S, Deppe AC, Slottosch I, Choi YH, Wahlers T. Preoperative statin therapy in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of 90,000 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:17–26. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffredo L, Angelico F, Perri L, Violi F. Upstream therapy with statin and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. Review of the literature and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi S, Sovari AA, Dudley SC Jr. Atrial fibrillation: the emerging role of inflammation and oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10:262–268. doi: 10.2174/187152910793743850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Dokainish H, Tsai P, Lakkis N. Update on the association of inflammation and atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:1064–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam O, Laufs U. Rac1-mediated effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) in cardiovascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1238–1250. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn JY, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen H, Liu D, Ping P, Weiss JN, Cai H. Oxidative stress in atrial fibrillation: an emerging role of NADPH oxidase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly SN, Jayaram R, Nahar K, Antoniades C, Verheule S, Channon KM, Alp NJ, Schotten U, Casadei B. Atrial sources of reactive oxygen species vary with the duration and substrate of atrial fibrillation: implications for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Circulation. 2011;124:1107–1117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs K, Baldus S, Klinke A. Fibrosis in atrial fibrillation - role of reactive species and MPO. Front Physiology. 2012;3:214. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AP, Reynolds WF. Statins downregulate myeloperoxidase gene expression in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue CW Jr, Creswell LL, Gutterman DD, Fleisher LA. Epidemiology, mechanisms, and risks: American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for the prevention and management of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2005;128(Suppl 2):9S–16S. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2_suppl.9s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, Goette A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:265–325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]