Abstract

Posttranslational addition of Arg to proteins, mediated by arginyltransferase ATE1 has been first observed in 1963 and remained poorly understood for decades since its original discovery. Recent work demonstrated the global nature of arginylation and its essential role in multiple physiological pathways during embryogenesis and adulthood and identified over a hundred of proteins arginylated in vivo. Among these proteins, the prominent role belongs to the actin cytoskeleton and the muscle, and follow up studies strongly suggests that arginylation constitutes a novel biological regulator of contractility. This review presents an overview of the studies of protein arginylation that led to the discovery of its major role in the muscle.

Discovery of protein arginylation and arginyl transfer enzyme (ATE1)

Protein arginylation was originally discovered in 1963, when it was found that ribosome-free extracts from cells and tissues exhibit prominent incorporation of specific radioactive amino acids. This phenomenon proved to be dependent on tRNA, but did not require any other components of the translation machinery. The amino acids were found to be transferred from aminoacyl tRNAs onto existing proteins, thus causing a posttranslational modification. Such ribosome-independent amino acid incorporation was first observed in prokaryotes using Leu and Phe [1–4], and subsequently was discovered in liver extracts using Arg [5, 6]. Attempts to observe incorporation of other amino acids in a similar way had failed, showing that this new mechanism is indeed specific to Leu/Phe in bacteria and Arg in mammals. All the accumulating evidences then indicated that this discovery represents a true posttranslational modification [6–8].

In summary, at the time of the discovery it was found that (i) this system is independent of regular conventional protein synthesis, and (ii) this system depends on a new enzyme that modifies the existing proteins by addition of Arg [1–3, 6, 9]. Thus, this system was originally named “soluble amino acid incorporation system”. However, International Enzyme Nomenclature Commission headed by late Dr. Waldo Cohn during the late 1970s decided that the official name for this protein should be Arginyl-tRNA Protein Transferase.

It should be noted that amino acid addition to proteins is not a unique phenomenon in eukaryotic systems, which also contain enzymes mediating posttranslational glycylation (addition of Gly [10]), glutamylation (addition of Glu [11]), and tyrosination (addition of Tyr [12, 13]) (see also [14, 15] for recent reviews). But these other modifications, described primarily for tubulin, do not utilize aminoacyl-tRNA.

Studies in different systems resulted in biochemical identification of this enzyme in plants [16] and in guinea-pig hair follicles [17]. In 1990, this enzyme was cloned and characterized in yeast, receiving its current name ATE1 (for Arginyl Transfer Enzyme [18]). Since ATE1 transfers Arg from arginyl tRNA, the arginylation reaction depends on Arg-tRNA synthetase activity in cells [19]. Later studies identified Ate1 genes in multiple species, and it is now known that ATE1 is present in all eukaryotes [16, 18, 20, 21]. In mice and human (and possibly some of the lower species), Ate1 gene encodes at least four isoforms generated by alternative splicing [20–22]. While evidence indicates that these isoforms have different activity, tissue expression, and substrate specificity, the functional distinction between these isoforms in vivo remains unclear.

Biological pathways regulated by arginylation

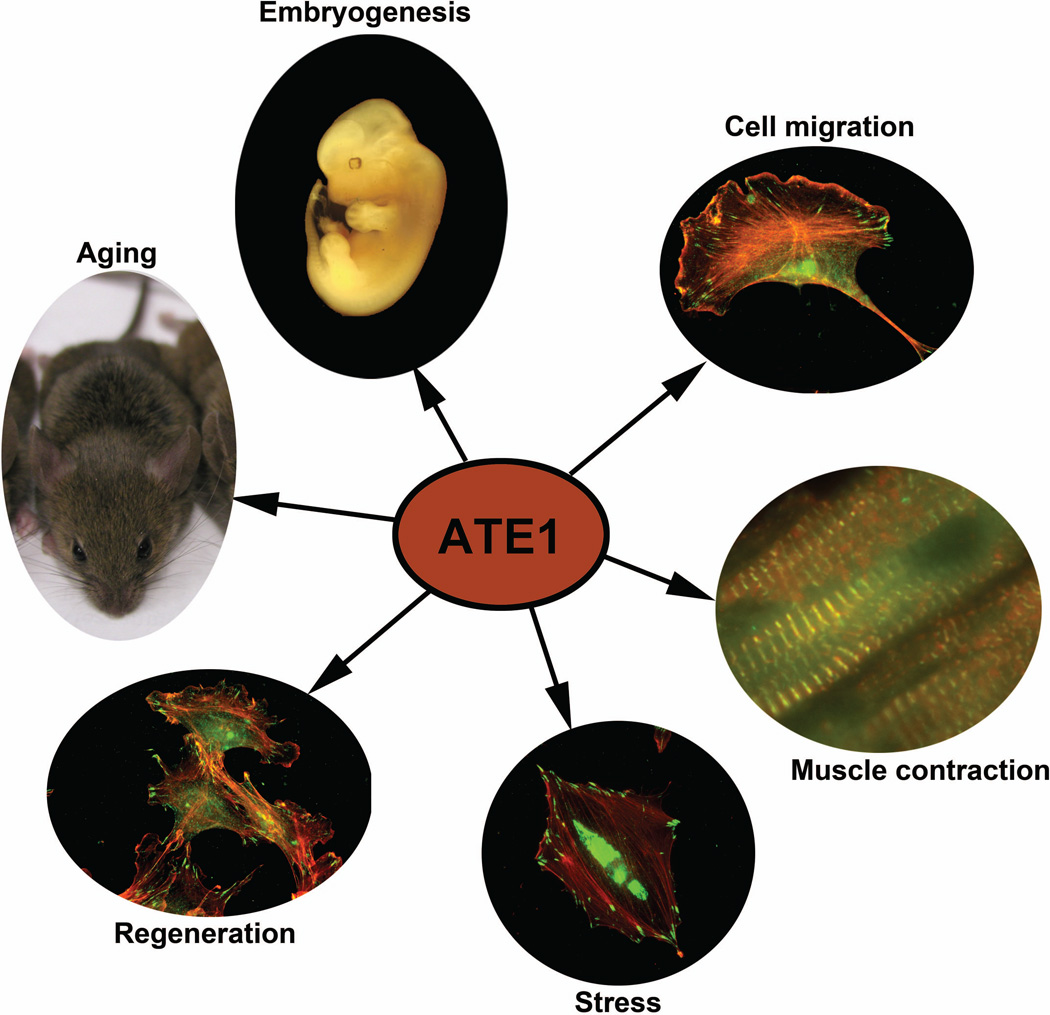

Ate1 knockout in yeast does not affect their viability [18], a finding that triggered the long-term label for arginylation as a “non-essential” process. However, later studies in other biological systems demonstrated that this was, in fact, far from true. A series of later studies implicated arginylation in regulation of embryogenesis [23] aging [24, 25], stress and heat shock , [26–28], regenerative processes [29–32], and protein degradation in the skeletal muscle [33]. In mice, Ate1 knockout results in embryonic lethality, abnormal cardiac morphogenesis, and impaired angiogenesis. Detailed analysis of tissue-specific and complete Ate1 knockout mouse models reveals defects in neural crest-dependent craniofacial morphogenesis [34], the formation and contractility of the cardiac muscle [35], and abnormalities in gametogenesis [36]. Postnatal deletion of Ate1 affects multiple physiological systems, leading to weight loss, mental retardation, and infertility [37]. Ate1 deletion in Arabidopsis thaliana leads to delayed leaf senescence [38, 39], defective shoot and leaf development [40] and abnormal seed germination [41]. Genomic screens show that while Ate1 does not affect viability of C. elegans it leads to embryonic lethality in Drosophila, suggesting that the key physiological systems that depend on arginylation for survival have evolved somewhere between these species [42]. Thus, arginylation is essential in many eukaryotic systems and is implicated in a number of physiological pathways (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Major biological pathways regulated by arginylation.

Identification of arginylated proteins in vivo

Ever since the original discovery of arginylation in 1963, the biggest question in the field revolved around the identity of proteins arginylated in vivo, which would likely point to its biological role as well as to its specific intracellular functions. However, identification of arginylated proteins remained an elusive task, largely due to the fact that Arg added to proteins by the action of ATE1 would be too similar to that incorporated by conventional translation, and thus any distinction of posttranslationally arginylated proteins from the bulk of proteins produced via translation is extremely difficult.

Early studies attempted to tackle arginylated protein identification by using various protein and peptide substrates in an in vitro reaction which utilized enriched ribosome-free fractions from cell extracts as the source of ATE1 activity. Other strategies involved developing methods for observing translation-independent Arg incorporation by inhibiting protein synthesis and detecting protein bands on the gel that contain radioactively labeled added Arg. Using these methods, it was found that Arg can be incorporated into membranes and chromatin [6, 9, 43], as well as dozens of gel bands in preparations from different tissues and/or different species [44], [24, 45–47], [48–50]. In vitro and in vivo ATE1 targets identified in earlier studies include ornithine decarboxylase [51–53], regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) [54, 55], BSA, alpha-lactalbumin, and thyroglobulin, (arginylated on the N-terminus after the removal of signal peptides [19, 56]). Another class of ATE1 targets includes regulatory peptides and hormones, including neurotensin (identified in vivo, [57], as well as in-vitro-tested beta-melanocyte stimulating hormone [58], insulin [59], and angiotensin II [58]. A pattern that emerged in the course of these studies suggested only one commonality: ATE1 appeared to exhibit strong preference to proteins and peptides containing N-terminally exposed acidic residues, Asp or Glu.

A new era in identification of arginylated proteins opened after the development of high precision mass spectrometry methods, which enabled higher throughput screens that could reveal in vivo proteins and peptides containing posttranslationally added Arg [60, 61]. This analysis has enabled identification of multiple additional arginylated proteins in complex samples from different tissues and cell types, expanding the list of known arginylated proteins to hundreds and suggesting that this posttranslational modification can potentially play a truly global role. In addition, this analysis suggested that N-terminal arginylation in vivo may not be restricted to Asp and Glu. Multiple peptides containing posttranslationally added Arg on the N-terminus of virtually every other exposed amino acid residue were also discovered. To date, it is not clear whether this new type of arginylation is also mediated by ATE1 or if other arginyltransferases with different substrate specificity also exist in vivo. It is clear, however, that the studies of protein arginylation and its specificity are still in the beginning stages.

Functional consequences of arginylation on protein targets

Identification of ATE1 as the enzyme mediating arginylation (Balzi 1990) came in the wake of the discovery of the N-end rule pathway of protein degradation, which relates the identity of the N-terminal residue to the protein’s half-life. According to these studies, test substrates engineered to include N-terminally exposed Arg are metabolically unstable in yeast [62, 63]. Furthermore, engineered proteins which contained N-terminal Asp and Glu undergo N-terminal arginylation in yeast, rendering them metabolically unstable [63–65]. Independently it was also found that N-terminal Arg attracts Ub conjugation machinery, which can lead to protein ubiquitination and degradation [66]. All this evidence converged into a prevailing view that arginylation in vivo constitutes a mechanism for degradation of pre-processed proteins or proteolytic fragments that bear Asp and Glu on their N-termini.

Recent functional studies expanded this view, suggesting that protein degradation may not be the only, or even the prevalent function of arginylation. First, these screens themselves, performed on protein fractions isolated from wild type (i.e., arginylation-positive) cell and tissue extracts, relied on abundance of arginylated proteins, and thus were naturally biased against those proteins which are metabolically unstable after arginylation. Functional studies on some of these proteins further confirmed that arginylation may have nothing to do with regulation of their metabolic stability. Arginylation of calreticulin during the ER stress facilitates its role in stress granules rather than cause its removal from the cells [67–70]. Arginylation of beta amyloid protein was suggested to facilitate its alpha helical conformation, preventing its pathological misfolding and accumulation [71]. Arginylation of a proteolytic fragment of the cell adhesion protein talin mediates its novel role in cell-cell adhesion [72]. Arginylation of myosin in platelets affects its regulation by prosphorylation and its normal contractility [73]. N-terminal arginylation of beta actin facilitates cell migration [74] and actin polymerization in vivo [75], independently of proteasome-mediated degradation.

In the case of beta actin, an unexpected link to arginylation-dependent degradation suggests that such degradation is likely responsible for removal of the closely homologous gamma actin if it becomes incorrectly arginylated in cells. Such selection occurs through an unconventional mechanism that relates mRNA coding sequence to protein stability and translation rates [76]. Thus, in the case of actins (and possibly other closely homologous but selectively arginylated protein isoforms), ubiquitin-dependent degradation appears to be a mechanism to ensure the selectivity of arginylation toward specific protein targets.

However, other lines of studies continue to argue toward the “conventional” degradation-dependent function of ATE1. Arginylation renders RGS4 and RGS5 metabolically unstable [54, 55]. Since these proteins negatively regulate cardiac morphogenesis, this mechanism may possibly be responsible for cardiac abnormalities seen in Ate1 knockout mouse embryos [23], which can potentially be explained by accumulation of RGS in the absence of arginylation. Arginylation has also been implicated in targeting oxidized proteins [59] and proposed to regulate oxygen sensing [54, 77]. It is likely that both degradation-dependent and degradation-independent effects play a role in protein regulation by arginylation in vivo.

Mid-Chain Arginylation of Intact Proteins

A recent discovery of a new type of arginylation, on midchain sites of intact proteins, has significantly expanded the potential biological scope of arginylation.

All the past screens and identification strategies for proteins arginylated in vivo relied on the postulate that proteins can only be arginylated at the N-terminus. This postulate originated from the assumption that a reaction of amino acid addition to a protein that utilizes charged tRNA must resemble the peptide elongation step on the ribosome (and thus must target the amino group of the N-terminal residue). Later on, the discovery and characterization of the N-end rule pathway reinforced the impression that arginylation, as a branch of this pathway, concerns exclusively the protein’s N-terminus. However, since arginylation by ATE1 was clearly prevalent toward Asp and Glu, this assumption meant that intact proteins can never be arginylated (since they all start with the N-terminal Met), and that only the action of specific aminopeptidases and proteases can expose the target site for arginylation. This, in turn, limited the potential pool of arginylation substrates to a subset of proteins that must be pre-processed prior to arginylation.

An apparent contradiction to this postulate emerged with the discovery that the biological peptide neurotensin can be isolated from an in vivo neuropeptide fraction with Arg added to a midchain Glu [57]. While there was no indication in this study whether this midchain reaction could be performed by ATE1 and whether it occurred on other peptides or proteins, it opened a possibility that arginylation in vivo may happen by different mechanisms that enable modification of intact proteins, in addition or instead of the conventionally postulated mechanism of Arg addition to the N-terminus.

A recent study performed a mass spectrometry screen without imposing the N-terminus restriction and assuming that Arg can be added to any Asp and Glu residue regardless of its position within the peptide (Wang et al, in press). Remarkably, screening under these conditions revealed a large number of proteins modified on midchain Asp and Glu in otherwise intact sequence. Follow-up studies showed that this reaction could be directly mediated by ATE1 in addition to the N-terminal reaction. Moreover, evidence suggested that midchain addition of Arg may be prevalent in the case of protein rather than peptide substrates. This discovery greatly expands the potential biological scope of arginylation, suggesting that in addition to protein fragments and pre-processed proteins it may also regulate intact proteins similarly to other global posttranslational modifications.

Regulation of arginylation

One of the big questions that remains relatively unexplored in protein arginylation field is the question of how this posttranslational modification is regulated in vivo. ATE1 expression exhibits a prominent peak at mid-development [20] and decreases during aging [24]. ATE1 levels can also vary significantly in different tissues [21]. Various proteins, drugs, and physiological compounds can significantly affect posttranslational Arg incorporation in vivo, however most of them are likely acting via non-specific mechanisms (see [42] for a recent review). It is feasible to imagine that proteins or non-protein inhibitors may exist in vivo that could potentially regulate the ATE1 enzyme itself or its molecular complex in vivo.

Another well characterized regulator of arginylation involves ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. For those proteins which are rendered metabolically unstable after arginylation, ubiquitin can facilitate their rapid removal. As demonstrated in the case of beta and gamma actin [72], this mechanism can efficiently facilitate arginylation specificity and ensure the removal of closely homologous proteins that were not meant to be arginylated in vivo.

Finally, an attractive, but so far hypothetical activity that could regulate arginylation in vivo involves de-arginylation enzyme(s), which may be capable of removal of posttranslationally added Arg from protein substrates. The action of these enzymes, if they exist, is expected to resemble the action of previously characterized Aminopeptidase B (which can remove Arg from the protein and peptide N-terminus) and Carboxypeptidase B (which can in principle remove Arg from the side chain carboxyl groups). Finding whether these or other similar enzymes may be involved in regulation of arginylation in vivo constitutes an exciting direction of further studies.

Arginylation as a regulator of cardiac contractility and the heart muscle

One of the main originally described phenotypes in arginylation-deficient ATE1 knockout mouse was a defect of cardiac morphogenesis, resulting in severe malformations and hypoplasia of the heart [23]. Follow-up studies showed that in addition to these gross morphogenic defects the cardiac muscle was also severely malformed, with multiple abnormalities in the myofibril structure leading to defects in cardiac contractility and likely contributing to embryonic lethality in these mice. These results suggested that the heart in general and cardiac myofibrils in particular constitute a major physiological system regulated by arginylation.

To dissect the specific role of ATE1 in the heart, a conditional knockout mouse line was constructed, in which targeted deletion of ATE1 was confined to the heart muscle (driven by alpha myosin heavy chain promoter that activates in differentiated cardiomyocytes)[78]. In these mice, cardiac morphogenesis occurred normally, suggesting that these early morphogenic defects are not specific to cardiomyocytes and/or originate at stages preceding heart formation in the embryo. However, the myofibrils from ATE1-deficient hearts showed defects largely similar to those observed in the embryos of complete ATE1 knockout (Fig. 2), suggesting that the formation and contractility of myofibrils within the cardiomyocytes depends on arginylation in these cells. With age, these heart-specific ATE1 knockout mice developed severe dilated cardiomyopathy and thrombosis, leading to high rates of lethality due to heart failure after 6 months of age.

Figure 2.

Knockout of arginyltransferase ATE1 leads to major defects in the heart muscle. Electron micrographs of wild type (WT) and ATE1 knockout (KO) muscle show diffuse Z-bands, irreglar sarcomere lengths, and overall disintegration of the cardiac myofibrils, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. See [78] for further details.

Mass spectrometry analysis of the isolated myofibrils identified a limited subset of proteins that are arginylated, most of them implicated directly in contractility and/or in the maintenance of the structural integrity of the myofibrils (Table 1). Their identity also raised a possibility that regulation of the muscle structure and contractility by arginylation may constitute a general mechanism that also affects other types of muscle and regulates their properties, interactions, and possibly metabolic stability.

Table 1.

Arginylated proteins in cardiac myofibrils.

| Name | Accession | Arginylated Residue |

|---|---|---|

| alpha actinin 2 | NP_150371.4 | L510 |

| fibrillin 1 | NP_032019.2 | E640**, Q671, L1266, E1794* |

| laminin gamma 1 | NP_034813.2 | E803* |

| myosin heavy polypeptide 6 | NP_034986.1 | L747^, K999^, L1001^, **, V1027^, L1486^, Q1534, L1578*, N1647 |

| myosin light polypeptide 3 | NP_034989.1 | A20, T81**, M117 |

| titin N2B | NP_082280.2 | L7960, V15013, C24818* |

| tropomyosin alpha-1 | NP_077745.2 | L50, K77 |

| cardiac troponin T2 | NP_001123650.1 | A184 |

also found arginylated in myosin heavy polypeptide 7 (Myh7; NP_542766.1; L745, K997, L999, V1025, L1484, and L1576)

found as monomethylated Arg as desribed in [79]

found as dimethylated Arg as desribed in [79]

Uncovering the exact role of arginylation on each of these sites constitutes an exciting direction of further studies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM104003 to A.K.

References

- 1.Kaji A, Kaji H, Novelli GD. A soluble amino acid incorporating system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1963;10:406–409. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaji A, Kaji H, Novelli GD. Soluble Amino Acid-Incorporating System. Ii. Soluble Nature of the System and the Characterization of the Radioactive Product. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:1192–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaji A, Kaji H, Novelli GD. Soluble Amino Acid-Incorporating System. I. Preparation of the System and Nature of the Reaction. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:1185–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Momose K, Kaji A. Soluble amino acid-incorporating system. 3. Further studies on the product and its relation to the ribosomal system for incorporation. J Biol Chem. 1966;241(14):3294–3307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaji H, Novelli GD, Kaji A. A Soluble Amino Acid-Incorporating System from Rat Liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;76:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaji H. Further studies on the soluble amino acid incorporating system from rat liver. Biochemistry. 1968;7(11):3844–3850. doi: 10.1021/bi00851a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soffer RL. The arginine transfer reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;155(1):228–240. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(68)90352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemper B, Habener JF. Non-rebosomal incorporation of arginine into a specific protein by a cell-free extract of parathyroid tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;349(2):235–239. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(74)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaji H, Rao P. Membrane modification by arginyl tRNA. FEBS Lett. 1976;66(2):194–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redeker V, Levilliers N, Schmitter JM, Le Caer JP, Rossier J, Adoutte A, Bre MH. Polyglycylation of tubulin: a posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science. 1994;266(5191):1688–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.7992051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kann ML, Soues S, Levilliers N, Fouquet JP. Glutamylated tubulin: diversity of expression and distribution of isoforms. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55(1):14–25. doi: 10.1002/cm.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arce CA, Rodriguez JA, Barra HS, Caputo R. Incorporation of L-tyrosine, L-phenylalanine and L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine as single units into rat brain tubulin. Eur J Biochem. 1975;59(1):145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallak ME, Rodriguez JA, Barra HS, Caputto R. Release of tyrosine from tyrosinated tubulin. Some common factors that affect this process and the assembly of tubulin. FEBS Lett. 1977;73(2):147–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulinski JC. Tubulin Posttranslational Modifications: A Pushmi-Pullyu at Work? Developmental Cell. 2009;16(6):773–774. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond JW, Cai D, Verhey KJ. Tubulin modifications and their cellular functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manahan CO, App AA. An Arginyl-Transfer Ribonucleic Acid Protein Transferase from Cereal Embryos. Plant Physiol. 1973;52(1):13–16. doi: 10.1104/pp.52.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lock RA, Harding HW, Rogers GE. Arginine transferase activity in homogenates from guinea-pig hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 1976;67(5):582–586. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balzi E, Choder M, Chen WN, Varshavsky A, Goffeau A. Cloning and functional analysis of the arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase gene ATE1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(13):7464–7471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciechanover A, Ferber S, Ganoth D, Elias S, Hershko A, Arfin S. Purification and characterization of arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase from rabbit reticulocytes. Its involvement in post-translational modification and degradation of acidic NH2 termini substrates of the ubiquitin pathway. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(23):11155–11167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon YT, Kashina AS, Varshavsky A. Alternative splicing results in differential expression, activity, and localization of the two forms of arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase, a component of the N-end rule pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(1):182–193. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai R, Kashina A. Identification of mammalian arginyltransferases that modify a specific subset of protein substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(29):10123–10128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504500102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu RG, Brower CS, Wang H, Davydov IV, Sheng J, Zhou J, Kwon YT, Varshavsky A. Arginyltransferase, its specificity, putative substrates, bidirectional promoter, and splicing-derived isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(43):32559–32573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon YT, Kashina AS, Davydov IV, Hu RG, An JY, Seo JW, Du F, Varshavsky A. An essential role of N-terminal arginylation in cardiovascular development. Science. 2002;297(5578):96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1069531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamon KD, Kaji H. Arginyl-tRNA transferase activity as a marker of cellular aging in peripheral rat tissues. Exp Gerontol. 1980;15(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaji H, Hara H, Lamon KD. Fixation of cellular aging processes by SV40 virus transformation. Mech Ageing Dev. 1980;12(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(80)90095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamon KD, Vogel WH, Kaji H. Stress-induced increases in rat brain arginyl-tRNA transferase activity. Brain Res. 1980;190(1):285–287. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bongiovanni G, Fissolo S, Barra HS, Hallak ME. Posttranslational arginylation of soluble rat brain proteins after whole body hyperthermia. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56(1):85–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<85::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao P, Kaji H. Effect of temperature on arginine incorporation by ribosomeless extracts of cells transformed by a temperature-sensitive mutant of Rous sarcoma virus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;477(4):394–403. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(77)90257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka Y, Kaji H. Incorporation of arginine by soluble extracts of ascites tumor cells and regenerating rat liver. Cancer Res. 1974;34(9):2204–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty G, Ingoglia NA. N-terminal arginylation and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in nerve regeneration. Brain Res Bull. 1993;30(3–4):439–445. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90276-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu NS, Chakraborty G, Hassankhani A, Ingoglia NA. N-terminal arginylation of proteins in explants of injured sciatic nerves and embryonic brains of rats. Neurochem Res. 1993;18(11):1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/BF00978361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YM, Ingoglia NA. N-terminal arginylation of sciatic nerve and brain proteins following injury. Neurochem Res. 1997;22(12):1453–1459. doi: 10.1023/a:1021998227237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon V, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. The N-end rule pathway catalyzes a major fraction of the protein degradation in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(39):25216–25222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurosaka S, Leu NA, Zhang F, Bunte R, Saha S, Wang J, Guo C, He W, Kashina A. Arginylation-dependent neural crest cell migration is essential for mouse development. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(3):e1000878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rai R, Wong CC, Xu T, Leu NA, Dong DW, Guo C, McLaughlin KJ, Yates JR, 3rd, Kashina A. Arginyltransferase regulates alpha cardiac actin function, myofibril formation and contractility during heart development. Development. 2008;135(23):3881–3889. doi: 10.1242/dev.022723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leu NA, Kurosaka S, Kashina A. Conditional Tek promoter-driven deletion of arginyltransferase in the germ line causes defects in gametogenesis and early embryonic lethality in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brower CS, Varshavsky A. Ablation of arginylation in the mouse N-end rule pathway: loss of fat, higher metabolic rate, damaged spermatogenesis, and neurological perturbations. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida S, Ito M, Callis J, Nishida I, Watanabe A. A delayed leaf senescence mutant is defective in arginyl-tRNA:protein arginyltransferase, a component of the N-end rule pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;32(1):129–137. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:115–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graciet E, Walter F, Maoileidigh DO, Pollmann S, Meyerowitz EM, Varshavsky A, Wellmer F. The N-end rule pathway controls multiple functions during Arabidopsis shoot and leaf development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(32):13618–13623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906404106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holman TJ, Jones PD, Russell L, Medhurst A, Ubeda Tomas S, Talloji P, Marquez J, Schmuths H, Tung SA, Taylor I, Footitt S, Bachmair A, Theodoulou FL, Holdsworth MJ. The N-end rule pathway promotes seed germination and establishment through removal of ABA sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(11):4549–4554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saha S, Kashina A. Posttranslational arginylation as a global biological regulator. Dev Biol. 2011;358(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaji H. Amino-terminal arginylation of chromosomal proteins by arginyl-tRNA. Biochemistry. 1976;15(23):5121–5125. doi: 10.1021/bi00668a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohley P, Kopitz J, Adam G, Rist B, von Appen F, Urban S. Post-translational arginylation and intracellular proteolysis. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1991;50(4–6):343–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallak ME, Barra HS, Caputto R. Posttranslational incorporation of [14C]arginine into rat brain proteins. Acceptor changes during development. J Neurochem. 1985;44(3):665–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb12865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takao K, Samejima K. Arginyl-tRNA-protein transferase activities in crude supernatants of rat tissues. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22(9):1007–1009. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallak ME, Bongiovanni G, Barra HS. The posttranslational arginylation of proteins in different regions of the rat brain. J Neurochem. 1991;57(5):1735–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb06375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner BJ, Margolis JW. Post-translational arginylation in the bovine lens. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53(5):609–614. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fissolo S, Bongiovanni G, Decca MB, Hallak ME. Post-translational arginylation of proteins in cultured cells. Neurochem Res. 2000;25(1):71–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1007539532469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao P, Kaji H. Comparative studies on isoaccepting arginyl tRNAs from transformed cells and their utilization in post-translational protein modification. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;181(2):591–595. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kopitz J, Rist B, Bohley P. Post-translational arginylation of ornithine decarboxylase from rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1990;267(2):343–348. doi: 10.1042/bj2670343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bohley P, Kopitz J, Adam G. Surface hydrophobicity, arginylation and degradation of cytosol proteins from rat hepatocytes. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1988;369(Suppl):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bohley P, Kopitz J, Adam G. Arginylation, surface hydrophobicity and degradation of cytosol proteins from rat hepatocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;240:159–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1057-0_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davydov IV, Varshavsky A. RGS4 is arginylated and degraded by the N-end rule pathway in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(30):22931–22941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee MJ, Tasaki T, Moroi K, An JY, Kimura S, Davydov IV, Kwon YT. RGS4 and RGS5 are in vivo substrates of the N-end rule pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(42):15030–15035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507533102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soffer RL. Enzymatic modification of proteins. 4. Arginylation of bovine thyroglobulin. J Biol Chem. 1971;246(5):1481–1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eriste E, Norberg A, Nepomuceno D, Kuei C, Kamme F, Tran DT, Strupat K, Jornvall H, Liu C, Lovenberg TW, Sillard R. A novel form of neurotensin post-translationally modified by arginylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(42):35089–35097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soffer RL. Enzymatic arginylation of beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and of angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(7):2626–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang N, Donnelly R, Ingoglia NA. Evidence that oxidized proteins are substrates for N-terminal arginylation. Neurochem Res. 1998;23(11):1411–1420. doi: 10.1023/a:1020706924509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong CCL, Xu T, Rai R, Bailey AO, Yates JR, Wolf YI, Zebroski H, Kashina A. Global Analysis of Posttranslational Protein Arginylation. PLoS Biology. 2007;5(10):e258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu T, Wong CCL, Kashina A, Yates JR., III Identification of posstranslationally arginylated proteins and peptides by mass spectrometry. Nature Protocols. 2009;43(3):325–332. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986;234(4773):179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonda DK, Bachmair A, Wunning I, Tobias JW, Lane WS, Varshavsky A. Universality and structure of the N-end rule. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(28):16700–16712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule. Cell. 1992;69(5):725–735. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90285-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Varshavsky A. The N-end rule. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1995;60:461–478. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elias S, Ciechanover A. Post-translational addition of an arginine moiety to acidic NH2 termini of proteins is required for their recognition by ubiquitin-protein ligase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(26):15511–15517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpio MA, Decca MB, Lopez Sambrooks C, Durand ES, Montich GG, Hallak ME. Calreticulin-dimerization induced by post-translational arginylation is critical for stress granules scaffolding. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(7):1223–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez Sambrooks C, Carpio MA, Hallak ME. Arginylated calreticulin at plasma membrane increases susceptibility of cells to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(26):22043–22054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carpio MA, Lopez Sambrooks C, Durand ES, Hallak ME. The arginylation-dependent association of calreticulin with stress granules is regulated by calcium. Biochem J. 2010;429(1):63–72. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Decca MB, Carpio MA, Bosc C, Galiano MR, Job D, Andrieux A, Hallak ME. Post-translational arginylation of calreticulin: a new isospecies of calreticulin component of stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(11):8237–8245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608559200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bongiovanni G, Fidelio GD, Barra HS, Hallak ME. The post-translational incorporation of arginine into a beta-amyloid peptide increases the probability of alpha-helix formation. Neuroreport. 1995;7(1):326–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang F, Saha S, Kashina A. Arginylation-dependent regulation of a proteolytic product of talin is essential for cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(6):819–836. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lian L, Suzuki A, Hayes V, Saha S, Han X, Xu T, Yates JR, Poncz M, Kashina A, Abrams CS. Loss of ATE1-mediated arginylation leads to impaired platelet myosin phosphorylation, clot retraction, and in vivo thrombosis formation. Haematologica. 2013 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.093047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karakozova M, Kozak M, Wong CC, Bailey AO, Yates JR, 3rd, Mogilner A, Zebroski H, Kashina A. Arginylation of beta-actin regulates actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Science. 2006;313(5784):192–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1129344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saha S, Mundia MM, Zhang F, Demers RW, Korobova F, Svitkina T, Perieteanu AA, Dawson JF, Kashina A. Arginylation regulates intracellular actin polymer level by modulating actin properties and binding of capping and severing proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(8):1350–1361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang F, Saha S, Shabalina SA, Kashina A. Differential arginylation of actin isoforms is regulated by coding sequence-dependent degradation. Science. 2010;329(5998):1534–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1191701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu RG, Sheng J, Qi X, Xu Z, Takahashi TT, Varshavsky A. The N-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature. 2005;437(7061):981–986. doi: 10.1038/nature04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kurosaka S, Leu NA, Pavlov I, Han X, Ribeiro PA, Xu T, Bunte R, Saha S, Wang J, Cornachione A, Mai W, Yates JR, 3rd, Rassier DE, Kashina A. Arginylation regulates myofibrils to maintain heart function and prevent dilated cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53(3):333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]