High schools can create a college-going culture that helps students visualize themselves in college, create strategic plans for reaching their postsecondary aspirations, and support school personnel in making college a reality regardless of family income and other economic and social constraints.

Young children dream of becoming firemen, doctors, and teachers; those in middle school imagine themselves as athletes, actors, and criminal investigators. By sophomore year in high school, the overwhelming majority of adolescents expect to attend college, often at elite institutions such as Harvard or Stanford University. Jobs become less defined as the choices for how to acquire them become more immediate. For many students, their dreams of attending highly competitive, expensive private schools are as unrealistic as becoming a movie actor or professional athlete. College ambitions are pervasive, and while some students may set their sights on public state schools or two-year institutions, the overwhelming majority expect to attain a four-year degree and this does not significantly vary by social and economic resources or race and ethnicity. Part of the lack of realism can be traced to the ubiquitous societal view on the importance of college and the lack of information on what it takes to be accepted at a college both in terms of academic preparation and economic and social resources. Applying to a college that matches students’ interests, academic strengths and talents, and personal preferences, as well as family values and resources, is a complicated process.

Applying to and enrolling in postsecondary schools is challenging for all students and it can be especially difficult for low-income and first-generation college students.1 Selecting the right college is a complex undertaking, where access to information and other resources exacerbates existing educational inequalities. High schools serving primarily middle- and high-income students have considerable resources to promote the college-going process and are supported in their efforts by teachers who are poised and parents who are tenacious in furthering postsecondary aspirations. The situation in high schools serving low-income populations, located in urban or rural areas, is quite different. Oftentimes, the schools do not have the resources to offer advanced level courses or college guidance services, and parent knowledge of the college application process and financial aid options is limited.

Recently, a number of interventions have been designed to learn how best to help low-income students enroll and persist in college. These efforts are different from prior programs in that they are targeted at those students whose academic skills and talents would be better matched with more competitive postsecondary institutions and include specific procedures for assisting in the college application process including financial aid options. One of these interventions is the College Ambition Program (CAP), which takes a somewhat broader approach, trying to change the high school culture into one where students not only talk about going to college but also learn more about what it takes to be a competitive applicant and how to match interests with postsecondary options. This chapter describes the intricacies of the college-going process, components of the CAP model, and its implementation, results, and sustainability.

The complexity of the college search process

The experiences of adolescents in high school often determine the trajectory of their academic preparation, educational expectations, and career knowledge—all of which are critical for achieving post-secondary success. Recognizing the importance of advanced academic courses critical for college preparation, many states have increased their high school graduation requirements in subjects like mathematics and science. High schools serving middle- and high-income students tended to offer these courses even before such requirements existed. Not only do these schools have experience offering such courses and teachers with expertise in these subjects, there is support for the students to receive extra help to succeed in these courses. Additionally, parents often hire tutors to assist students not only in remedial courses but also those in advanced levels. In schools serving low-income students, extra help to succeed in these types of college preparation courses is not available nor do parents have the resources to hire tutors. The challenge for the high school is how to offer additional help for these types of courses—which fall outside of the remedial curriculum and courses for students with special needs. Thus, the very first and key part of the college-going process is to encourage students to take advanced level courses and to provide them with the support to succeed in these courses.

In addition to the academic challenges of being prepared for college, there is the actual application process itself. This can be especially difficult both personally and institutionally. On the personal side, students may aspire to certain types of jobs but are unaware of how much education is needed to achieve their goals. Referred to as having unaligned ambitions, this is most common among those students whose parents have not attended postsecondary school, although students in middle- and upper-class families can also be misinformed and overestimate how much education is required for certain jobs. Having unaligned ambitions can affect the types of programs and institutions students are interested in attending.2

Another challenge for students (particularly low income and minority) is “undermatching,” which is when students possess the necessary academic preparation to attend a more selective four-year institution, yet choose to attend a less-selective one and sometimes such institutions can end up being more expensive.3 Research examining those students who are undermatched indicates that they are less likely than their peers to complete their degree on time and are more likely to drop out of college altogether.4 One population that seems highly prone to undermatch are those high school students living in rural areas of the United States.5

On the institutional side, the process of seeking out, applying, and enrolling in college is increasing in complexity, driven in part by changes in university marketing and recruitment practices, and rising costs of college and institutional factors such as decreasing campus need-based aid.6 The process of researching, planning, and preparing to go to college is one that requires years of careful consideration, years that need to start well before the senior year. In many high schools with higher than average college attendance numbers, the college selection process heats up in the end of sophomore year with notices of when and how to prepare for college entrance exams and the possibility of applying for early admission. The early admission process begins in earnest in the junior year. Without interventions earlier in the secondary school experience, by senior year, many students who try to begin the college search process can become overwhelmed and simply give up or take a path of least resistance and apply to a local two-year college.

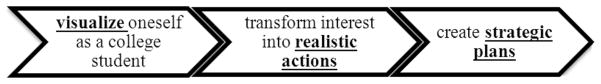

For all students, selecting colleges that align with their interests, skills, and talents requires a strategic planning process that relies on knowledgeable family and school personnel who can provide requisite information for making sound postsecondary choices. As shown in Figure 1.1, Schneider & Stevenson outlined key steps in acquiring the knowledge, skills, and mindsets necessary to be successful in the college search.7

Figure 1.1.

The college search: A theory of action

First, and perhaps most important, a student needs to visualize oneself as a college student. This means not only understanding what the college experience looks and feels like, but also being able to place herself in the shoes of a college student—knowing something about what is expected, the courses one should take, and how to manage their time. Second, a student needs to transform that vision into realistic actions by making tangible connections to actions that can help reach their goal. This might entail taking more rigorous courses, becoming involved in extracurricular activities, or seeking out tutoring to become more proficient in a subject area. Finally, once seeing the connections between the vision of college enrollment and specific actions in high school, a student creates a plan for securing financial aid, navigating relevant deadlines, and settling on where to live and how to make that happen. Parent and family resources in more affluent communities frequently support this third step (often referred to as “helicopter” parents), which often involves specific logistical knowledge and resources including frequent trips to colleges and explicitly going over the details of the first few weeks of postsecondary school. In school contexts with fewer resources, creating strategic plans becomes a much more challenging process, and a student can easily become overwhelmed and unsure of what information is required—from filling out housing forms to understanding what is owed for tuition, and when that amount has to be paid.

Assisting high school students in the college application process

There are a number of interventions currently in place that have been specifically designed to assist low-income students in the college-going process. Some of these focus on completing financial aid forms, others on coaching and mentoring models. Without a doubt, certain key behaviors, such as completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form and submitting on-time college applications, serve as gatekeepers for enrollment. However, focusing exclusively on these tasks has the potential to encourage students to fill out applications for the sake of filling them out, without receiving the necessary mindset and support for following through to enrollment. This is not to say that an effective school-wide program should not focus on FAFSA or college applications; rather, a comprehensive program should attend to these gatekeeping steps as part of a larger spectrum of microlevel shifts in students’ knowledge and attitudes toward college going.

In the past several years, funding and interest have increased in school-based models that place college advisors in low-income schools for a one- to two-year period.8 The advisor, or “coach,” model, functions somewhat akin to other education programs, such as Teach For America (TFA) and The Teaching Fellows (TF), which recruit high-performing, achievement-oriented recent college graduates, provide them with basic training and support, and then place them in high-needs schools. In the case of the National College Advising Corps (NCAC) and other coach models, advisors serve as college coaches, and work with seniors to fill out college applications and submit required financial aid forms. In many cases, coaches are affiliated with the school guidance staff in which they work and spend much of their time in one-on-one meetings with juniors and seniors. Coaches are an important part of developing and sustaining a college-going culture within a school while providing crucial services and support for students to attend college.

To be sure, there are certain advantages afforded by the coach model. For one, coaches tend to be young, driven, and often come from more diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds than most high school guidance staff. This could likely translate into strong relationships and trust between coaches and students, and encourage more students to follow their advice and apply for admission and aid. In addition, since most coaches tend to be recent college graduates, they are in a unique situation to mentor high school seniors, having just spent time in college and familiar with questions and apprehensions that seniors may have about beginning the process. This would likely improve the “take-up” of advice and counsel from coach to prospective student. College coaches are typically limited to a small set of college-related tasks, namely, working with upperclassmen to encourage filling out applications for admission and financial aid, as well as providing in-the-moment advice and mentoring during one-on-one sessions.

Supporting students in high school: The College Ambition Program

CAP is more holistic in its approach to college entrance and focuses not only on juniors and seniors, but is available to all students as the process begins well before the final two years of high school. Designed to promote a college-going culture in schools, CAP works to improve adolescents’ understanding of the educational requirements for a given career path and assists students in developing the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors to attain that goal. CAP includes four components: (1) tutoring and mentoring, (2) course counseling and advising, (3) financial aid planning and assistance, and (4) college experiences—visits to campuses. Leveraging near-age peers, low-cost mobile technology and texting, and university-based partnership, the CAP model not only supports the development of a college-going culture in high schools, but is built to be sustained by the school after the initial research/trial period ends.

Each of the four components primarily operates through a “CAP Center” that is open three days a week for six hours, including after school. This schedule is designed to be accessible to students while not disrupting class attendance during the day. The CAP Center is an integral part of the school rather than just a supplemental service. Announcements and signs are posted throughout the building, and CAP staff members are encouraged to make presentations in classes and attend school functions. Students are encouraged by their teachers and counselors to attend the Center for tutoring help and college preparation. A full-time CAP site coordinator organizes the mentors and other activities sponsored by CAP, including school-wide events and college visits.

CAP has developed an extensive set of activities, beginning when students first enter high school that helps them make more informed choices about courses and the steps for applying to different types of colleges. One programmatic aspect of CAP is to introduce students to colleges that have specialized programs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Low-income and minority students are underrepresented in STEM fields. Colleges and employers are actively recruiting STEM college majors and projections by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other federal agencies indicate that careers in STEM fields are likely to increase.9

Partnering with the schools’ counseling staff, CAP staff advises students on selecting courses that align with particular careers of interest and curriculum requirements for their individual needs. CAP offers tutorial help using undergraduate students for subjects in which students often have demonstrated difficulty—algebra, statistics, biology, chemistry, physics, and English—all of which are important for college admissions and entrance exams. These near-age undergraduate tutors (often of like race and ethnicity) are clear role models of successful college students. Trained not only to complete homework assignments, the tutors are available during CAP hours as well as after school for help and advice. CAP has been successful in recruiting honors students from local undergraduate STEM programs, who describe their experiences as “an opportunity to give back,” “a chance to help someone like me and the challenges I had,” and “learning more about who I am and whether working in a school is a possibility for my future.”

To address some of the financial pressures low-income families may face in paying for college, CAP has developed a series of materials that go beyond just assisting students through the FAFSA process. CAP supports students in searching for scholarships and additional grants, understanding how much money students are still responsible for after receiving scholarships and/or financial aid, and what actionable steps students and their families need to complete between college acceptance and matriculation in the fall. For example, CAP helps students prepare for invitational interviews to prestigious four-year colleges, relying on the expertise of one of the CAP coordinators who had previously worked in college admissions at an elite university. Additionally, CAP has worked with the law school to assist parents with immigration problems and tax issues that could prevent their children from receiving federal financial aid.

Even when low-income students receive acceptance into college and financial aid, some still fail to matriculate in the fall. CAP intensively works with graduating seniors in May to identify how much money the family and the student needs to begin college in the fall, what health insurance and other forms must be completed, how to plan for living arrangements, how to register for classes, and how to seek employment (especially work-study opportunities).

CAP has also designed a special training program for students visiting campuses to assist them in evaluating how the college fits their expectations. In contrast to various other programs or interventions that might offer college visits oftentimes only to high performing students, CAP provides this opportunity to all students at no cost and takes advantage of local programs and foundations that can support the costs associated with each trip. Prior to each visit, students prepare in advance—learning what to look for at each campus and what questions to ask admissions representatives while on the visit. This has been a beneficial experience for many of the students who have never been on a college campus even though they may live only twenty minutes away. Responses from college visit evaluations indicate for some students the visit helped to shape their views on the type of campus where they would feel more “at home” and able to succeed.

Summer outreach

Even if students successfully navigate the college application and selection process during high school, the summer between their graduation and the start of college has been found to be a vulnerable time in which students who intend to enroll in college fail to actually matriculate.10 This phenomenon is commonly referred to as “summer melt.” (See Chapter 4 in this volume.) Based on the research of summer melt, in the spring of 2012, CAP extended its near-age mentoring to a subsample of randomly selected students in the intervention schools as well as in a sample of matched comparison schools. Before graduation, seniors in both CAP and matched comparison schools were asked to fill out an exit survey which included questions about their future plans (attend a university, college, community college, trade school, and so on) and general levels of comfort with the financial aid, registration, and orientation process. Students were also asked to provide multiple means of contact, such as a mobile phone number or an email address.

Selected students were assigned to one of a small group of summer mentors, made up of current undergraduates and graduate students working on campus in the summer. Some mentors worked with CAP during the school year and some responded to a posted announcement on a university-wide service learning job/volunteer board. Each mentor attended a two-hour training with a CAP staff member that covered several topics, including maintaining students’ privacy and confidentiality, tips for mentoring adolescents, and a general background on the most common financial aid questions students might encounter. Following the templates created by Castleman et al., CAP developed a series of contact protocols tailored to specific issues and modes of interaction.11 These included an initial “intake” interview template and several different follow-up protocols for providing more in-depth assistance. One key finding coming out of the summer work was that text messaging serves as a low cost and efficient means of encouraging participation in CAP interventions. Our take-up rates were very close to the rate reported by Castleman et al., with nearly 60 percent of students responding to text message outreach.12 Take-up rates for email contact were much lower, at about 20 percent.

Reinforced by the need to reach students both in and out of school and the initial success of summer mentoring through texting support, in the 2012–2013 school year CAP implemented a randomized “microintervention.” This randomized within-school study allows for more accurate estimation of program effects at the student level as well as reaching more students through a more innovative medium—their cell phone. Advances in smartphone and mobile application (app) technology provide new ways for outreach, especially for adolescents. Using smartphones not only can expand the extent to which information and resources can reach students but it also can provide students with direct interaction and opportunities for obtaining follow-up information from the services.

The use of smartphones in education is also growing among the adolescent population, even those students from low-income households, with approximately one in three students using their phones for help on homework.13 Growth can also be seen in smart-phone companies that spend an estimated $20 billion a year on research and development. Contrast that to the annual spending of the National Science Foundation, around $250 million, it is evident that the ability to use smartphones to support students transitioning to adulthood is not only cutting edge, but is quickly becoming a necessity.

The microintervention experiment intended to provide data for measuring the effects by generating random variation in student participation in CAP through the use of a targeted “nudge.” Rather than directly assigning students to receive the CAP treatment, the probability that a random student takes the treatment is encouraged through the nudge text message with information or upcoming deadlines. This generates experimental-type conditions, but where conducting a randomized experiment is not a possibility (for example, limiting CAP services to a random sample of students within a high school).14 The strength of the encouragement is hypothesized to be driven by simple changes in students’ “default behaviors,” a concept which has been used to more generally motivate another college access intervention.15 In this context, the default behavior of most students is not to employ an available resource for college access (for example, the CAP center) that is nearly costless to the student and potentially quite beneficial.

The text messages were sent between 3:30 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. on three consecutive Mondays in the month of February. Each week, the text message highlighted a different aspect of CAP services, including help with college applications, filling out the FAFSA, and searching for scholarships and awards to reduce the cost of attendance. The full text of each message is below. (Note: each message is customized to match school characteristics, such as CAP center location, and so on.)

Week One: It’s not too late to apply for college! Most schools accept applications until March 1st or even later. Stop by CAP in Rm 305 today to get application help.

Week Two: Worried about paying for college? You could qualify for up to half off your college tuition. Stop by CAP in Rm 305 today to learn more about financial aid.

Week Three: Need help finding scholarships for college? Not sure where to look? The CAP Center in Rm 305 can help you find extra money for college. Stop by soon!

The research utilizing text messaging as part of CAP is preliminary and ongoing, but we expect that this will be a cost effective and efficient means of boosting CAP participation in treatment schools. More importantly, it provides within school randomized estimates of take-up. Based on results from first year of the nudge experiment, we find among those students who received the nudge compared to students who did not that the treated were more likely to visit the CAP center (t = 19, p < .0001). Given the relatively low cost of the intervention (about $6 per student), the limited labor required, and its ability to reach students personally, we are optimistic that this design will be useful in a larger set of treatment schools and as a practical way to get students knowledge and helpful information.

Preliminary findings

To measure the impact of CAP on college going, multiple measures were created and obtained from student, mentor, and teacher surveys, CAP coordinator logs and sign-in data, and intensive interviews with students, teachers, and other school staff. Items on CAP student questionnaires were drawn from national student surveys, which facilitate comparison of CAP survey data with nationally representative samples. Survey measures included items on postsecondary expectations, college ambition, perceptions of college cost, financial aid, various actors’ influence on the college planning/application process, students’ math and science perceptions, and demographic variables of interest. College enrollment and choice of major data are obtained from the senior exit survey. The CAP data are also augmented with additional data from school administrative records. After three years, the following briefly describes the first set of findings, from analyses of the surveys and interviews.

Student responses on surveys merged with state data were analyzed using several statistical procedures. The following results are based on six high schools in mid-Michigan that participated as either a treatment or a control school. Using pre- and postsurvey data from high school seniors in both treatment and control schools, the analysis examines the impact of the CAP intervention on seniors’ intent to enroll in postsecondary institution immediately after their high school graduation. This impact analysis employs logistic regression to measure several potential postsecondary intentions taken in the senior year including no college, attendance at a two-year college, and attendance at a four-year college and their eventual destinations fall 2012.16 Results from these inferential statistics indicate that among those students who participated in CAP in the first three years, students in urban schools were significantly less likely to expect to attend a four-year college compared to their counterparts in the rural schools; on average, urban students were 21 percentage points lower than rural students in their expectations. Minority students were also significantly less likely to expect to attend a four-year college, with a predicted probability 7 percentage points lower than nonminority students.

Consistent with previous research, males are more likely than females to pursue a degree in STEM; in our sample the predicted probability for males to be interested in a STEM major was 13.5 percentage points higher than the females. There was a difference between urban and rural schools in STEM major as well; the predicted probability for urban schools was 4 percentage points higher than rural schools. Examining the differences between the treatment and control schools, students in the treatment schools were more likely to show interest in pursuing a STEM major, with a difference in predicted probability of 5.7 percentage points.

A preliminary analysis of actual postsecondary enrollment rates with a partial sample of treatment schools shows a positive and significant treatment effect on all postsecondary enrollment (t = 29.90, p < .0001). The sample for this statistical analysis included a large sample (n > 1,000) of students in both treatment and control groups and made use of actual postsecondary enrollment data from 2006–2007 to 2010–2011. These results are consistent with prior simulation estimates using propensity-matching techniques with large national datasets.17 While we are encouraged by these results, they are still preliminary and do not meet the conditions by which one could estimate a causal link between treatment and enrollment. As we continue to add treatment schools and expand our control sample, we will further systematically and rigorously examine this relationship.

Student perspectives

In summer 2012, intensive qualitative interviews were conducted with a randomly selected group of seniors regarding their plans for the fall, what they were doing over the summer, and their expectations and concerns about graduating high school and entering college.18 These interviews provide a rich source of data that highlights the development and familial resources these students face, in combination with institutional, school-related problems. Preliminary findings point to issues of individuation and independence (that is, the developmental process of young adults including their self-concept, sense of responsibilities, and behaviors) in leaving home for college.19 Leaving home for college raises concerns among students even if they plan on living at home while attending community college.

One of the overriding themes from the interviews indicate that familial and parental support, often conceived of as a universal asset to developing college ambition, appears to function in highly complex ways in students’ lives. For example, there seems to be a difference between parental support in urban and rural families, where parental support in urban contexts encourages students to go out on their own, while parental support in rural contexts tends to encourage students to stay close to home for a longer period. The following quotes extracted from some of the interviews transcribed and coded for issues of self-esteem, independence, and strategic planning underscore these differences and illustrate how students’ development and familial resources interact with the school and academic context in transitioning from high school to college.

Miranda lives in a rural community and plans to pursue a career in the medical field. At first she thought about attending a four-year college but she worried that she was not ready for such a big transition. Her family is supporting her to attend a two-year college and live at home. “My parents wanted me to go to college and pushed that. I’ve talked to people older than me at CAP lab and stuff and I said my parents always pushed me to go. One student in the CAP center said, ‘Oh, my parents never did, that wasn’t even talked about.’ That was shocking to me, because my parents have always pushed that.” However, when it came time to complete the FAFSA, Miranda received less support. “My mom was really upset. She actually did a lot of it. She said if you don’t get anything from this then I’m not doing it again. I know they want you to do it every single year, but if you don’t benefit from it then why am I going to waste my time.”

Helen also lives in a rural area and plans to attend a four-year college in the fall. She discusses the lack of college resources in her life: “I don’t really talk to many people who have gone to college. I don’t get a chance to really talk to them. Because I’m not close enough to them to even care to ask. And I don’t want to get all personal with somebody if they’re not like a close friend. I don’t want to pry into their life or anything. So I usually just let it go.” She describes the resistance she faced from her aunt, who suggested that she pursue a two-year degree rather than attend a university. “[She] was all like ‘you couldn’t afford university anyways so you might as well just go to [community college]’ but Helen resolved, “I’m not going to let my financial situation hold me back from doing what I want to do.” She further explains the challenges of talking with her mother, who did not attend any postsecondary school. “She is hard to have a conversation with. She doesn’t understand anything.” Instead Helen has turned for help from a friend’s parent, “My best friend, Allie …her mom has helped me out a lot. Looking at all my stuff and showing me how to do everything. She helped me with the housing because she helped Allie do hers. These people are the ones that help me out …the ones that know what to do. My mom is kind of clueless.”

While the familial support may differ by context, both rural and urban first-generation students faced challenges in accessing the necessary information and resources. One urban two-year college-bound student, Sarafina, describes getting advice from others she knew, “And I was thinking to myself one day, well, how am I supposed to do all of this and college? And so I would ask other college students, [and] my sisters, because I trust them, and they’re all, ‘Oh no, it’s fine. You’re only going into class for a couple of hours for maybe one or two days a week’, and it’s like, ‘Ok, if you say so.’” She explains that she got information from counselors at school because, as a first-generation student, “My parents couldn’t really talk about it.”

Compared to the rural schools, the urban ones have more access to more resources, courses, and college-preparation materials. Sarafina describes the college preparation she received as a part of the International Baccalaureate Program (IB) at her school, “The IB teachers they say over and over and over again, more than any other teachers. This is a syllabus, this is what it’s going to be like in college; you might want to keep up.”

Helen (see above) on the other hand, discusses her frustration with the lack of adequate academic challenge and college preparation at her school. She compares her public school with the local Catholic school, explaining that the teachers have high standards and that the students there have higher test scores as a result. “We are just kind of like–left. I don’t think they did enough for us. I think they could have done more especially preparing us for college. We only offer two AP classes, AP biology and AP English. I didn’t do those. I took CP (college prep) English and even that was still a joke. Like, there was nothing college prep about it; our papers were worth ten points.”

Friends and peers appear to help one another contributing to the college-going attitudes and behaviors of each other. John, a rural student intending to transfer to a four-year college after starting at a community college, describes the way his friends supported each other to pursue their college goals, “They have similar goals, going for four-year degrees, or maybe a little more afterwards … Everybody is in the same boat asking questions senior year, ‘Where are you going to college? Do you think it’s going to be hard’ kind of questions. Everyone is working on each other.” An urban four-year college-bound student, Lloyd, describes the pressure he felt from his peers in honors classes to follow a similar path to college. “I take a lot of honors classes so most of the people in my classes are college bound. So I mean, I think they have influenced me a lot as far as the want to get good grades and the want to go to college and I mean everybody else around me is doing it, shoot, end up the only one not doing it.”

An urban two-year college-bound student, Brittany, describes the college press among her peers. “We always talked about college since we were freshman in high school. ‘What are you going to do? Where are you going to be?’ Like we were little kids still. ‘When I grow up I want to be this that and the other.’ So my friends and I, we stayed on track together. We always helped each other study. We always helped each other with homework. Sometimes we didn’t do homework, but we said, ‘Girl, we got to get that work done!’” Even when she had a baby in the middle of her junior year, her friends provided support to help her keep up. They would say, “‘If you need me to watch him so you can get something done, I’ll do it.’ They were more than ‘let me be there for you’ and I was like, Ok. So my friends influenced me by making sure I stayed on task and ‘do you need help with your homework’ ‘did you get what you missed when you had Jay?’ I got it. Thanks everybody. My friends are good.”

Sustainability, policy, and practical applications

CAP is specifically designed for low-income public high schools and seeks to operate at a relatively small price tag so that the lessons learned can be modeled into existing programs. One consideration for new intervention programs like CAP is to plan how to make these programs sustainable beyond two or three years—specifically, how to access and train human and intellectual resources in the school that can take over the school-wide intervention. One possible idea is to leverage younger teachers in the building who may be pursuing advanced degrees in educational leadership (required to become a building principal or district administrator). Most degree programs require teachers to take on a specific leadership role often focused on reaching struggling students. Another idea is to include time in the CAP center as part of the internship experience for beginning high school teachers. In the future, CAP will be working with the secondary teacher education program to determine if the training of high school teachers can incorporate such experiences into their programmatic requirements.

As the demand for a college-educated population increases, so have the numbers of interventions, many of which include components, such as training for counselors to improve their college counseling expertise, offering schools tutoring and mentoring staff, providing information and assisting students with filling out financial aid forms, and taking students on college visits. While helpful, these interventions typically focus on one aspect of the college-going process, and few deliver training for accessing and using the information that many parents and students need to understand the material they receive. In contrast to these one-dimensional reforms, CAP is specifically designed to be an intervention that comprehensively connects several important aspects of the college-going process. Extending support services to students through the use of text messaging as well over the summer through simple, cost-effective outreach might further increase the likelihood of students successfully fulfilling their postsecondary aspirations. The process of navigating the myriad challenges students face on the road to college enrollment cannot be solved by interventions that focus support on the senior year. Rather, a truly comprehensive approach must meet students in all grades (9–12) where they are, and begin to build skills and mindsets to smooth the process as they grow older. A fixation on the gatekeepers of college going ignores the many challenges low-income students face along the way, leading many to arrive at the gate, but far fewer to walk through.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Barbara Schneider, John A. Hannah Chair and University Distinguished Professor at Michigan State University.

Michael Broda, University Distinguished Fellow at Michigan State University.

Justina Judy, Doctoral candidate in Educational Policy and Economics of Education Fellow at Michigan State University.

Kri Burkander, Doctoral candidate in Educational Policy at Michigan State University.

Notes

- 1.Hoxby C, Avery C. NBER Working Paper 18586. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. The missing “One-Offs”: The hidden supply of high-achieving, low income students. [Google Scholar]; Hoxby C, Turner S. SIEPR Discussion Paper No 12–014. Stanford, CA: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research; 2013. Expanding college opportunities for high-achieving, low income students. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider B, Stevenson D. The ambitious generation: America’s teenagers, motivated but directionless. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roderick M, Coca V, Nagaoka J. Potholes on the road to college: High school effects in shaping urban students’ participation in college application, four-year college enrollment, and college match. Sociology of Education. 2011;84:178–211. [Google Scholar]; Smith J, Pender M, Howell J. The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. Economics of Education Review. 2013;32:247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen W, Chingos M, McPherson M. Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoxby, Avery 2012 [Google Scholar]; Smith J, Pender M, Howell J. The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. The College Board Advisory and Policy Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]; Schneider B, Broda M, Judy J. Improving postsecondary outcomes for low-income students. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Education Effectiveness (SREE) Spring 2013 Conference; Washington, DC. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinzie J, Palmer M, Hayek J, Hossler D, Jacob SA, Cummings H. Fifty years of college choice: Social, political and institutional influences on the decision-making process. 3. Vol. 5. Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation for Education; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider, Stevenson 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 8.See the National College Advising Corps. ( http://www.advisingcorps.org), and local- and state-level affiliates.

- 9.Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Employment projections: 2008–2018 summary. 2009 Retrieved October 20, 2011, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/ecopro12102009.htm.; National Science Board (NSB) Preparing the next generation of STEM innovators: Identifying and developing our nation’s human capital. Arlington, VA: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold KD, Fleming S, DeAnda MA, Castleman BL, Wartman KL, Price P. The summer flood: The invisible gap among low-income students. Thought and Action. 2009 Fall;:23–34. [Google Scholar]; Castleman BL, Arnold KD, Wartman KL. Stemming the tide of summer melt: An experimental study of the effect of post-high school summer intervention on low-income students’ college enrollment. The Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness. 2012;5(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castleman, et al. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castleman, et al. 2012 The data needed to make this inference is not available yet. In summer 2013, we expect to receive outcome data from the State of Michigan via the National Student Clearinghouse. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khadaroo ST. Not just 4 texting: 1 in 3 middle-schoolers uses smart phones for homework. The Christian Science Monitor. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Education/2012/1129/Not-just-4-texting-1-in-3-middle-schoolers-uses-smart-phones-for-homework.

- 14.Frangakis C, Rubin D, Zhou XH. Clustered encouragement design with individual noncompliance: Bayesian inference and application to Advance Directive Forms. Biostatistics. 2004;3(2):147–164. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrell S, Sacerdote B. Late interventions matter too: The case of college coaching in New Hampshire. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Data used in this analysis are restricted to students in the 12th grade during the 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 school year. This sample included a total of 1,070 12th grade students from the treatment and control high schools. The survey response rate across the schools was 80 percent

- 17.Schneider B, Khawand C, Judy J. The College Ambition Program: Improving opportunities for High School Students Transitioning to College. Paper presented at the spring conference of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness; Washington, DC. Mar, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkander K. Ambition in transition: Voices from rural and urban students regarding the transition from high school to college. 2013. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erikson EH. Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; Blos, P. (1967). The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1968;22:162–186. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1967.11822595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.