Dear Sir:

We appreciate the important work from Ng et al (1) characterizing the dose-response relation between vitamin D intake and changes in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations in African Americans. We are, however, concerned that their approach has resulted in considerable overestimation of the intake of vitamin D needed by this population group. Specifically, the researchers’ a priori determination that vitamin D adequacy is achieved when 97.5% of the population achieves serum concentrations of 20 ng/mL—the concentration linked to the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) value of the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs)—is a misuse of the RDA reference value as outlined by the Institute of Medicine (2, 3) and as discussed by others (4–6).

In short, the definition of adequacy used by Ng et al is inappropriate for application to population groups. One cannot infer that persons with measures below the RDA—or in this case, the RDA-associated serum concentration—are inadequate, because, by definition, the RDA-associated serum concentration reflects a value that exceeds the needs of most individuals (2). Many persons below the RDA value have adequate status because a dose-response (or intake-adequacy) relation reflects a distribution of values across a population. Given this inherent variability, the appropriate approach to achieve a low prevalence of inadequacy within a population group—as verified by statistical modeling—is to shift the intake distribution so that most of the population (97.5%) has intakes above the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), not above the RDA (3). The same approach applies to achieving serum values above the EAR-associated value, not above the RDA-associated value (6).

Therefore, the approach taken by Ng et al (1) should have been to estimate how much vitamin D is needed to ensure a low prevalence of serum 25(OH)D concentrations below that specified as the EAR-associated value (ie, 16 ng/mL), not how much is needed to ensure that 97.5% of the population group achieves serum concentrations associated with a cutoff defined as the RDA-associated measure (ie, 20 ng/mL). The latter approach “forces” the majority of the population group to achieve serum concentrations that are greater, often considerably greater, than those needed to ensure adequacy, and in turn artificially inflates the needed increase in intakes of the group being studied. As can be seen in Figure 3 of Ng et al, a notably lower dose would have been suggested if the solid line had been drawn at 16 ng/mL, rather than at 20 ng/mL. The Ng et al analysis will be of much interest to those working in the vitamin D field and should therefore be corrected to reflect the intake amount needed to reduce the number of African Americans with serum 25(OH)D concentrations <16 ng/mL.

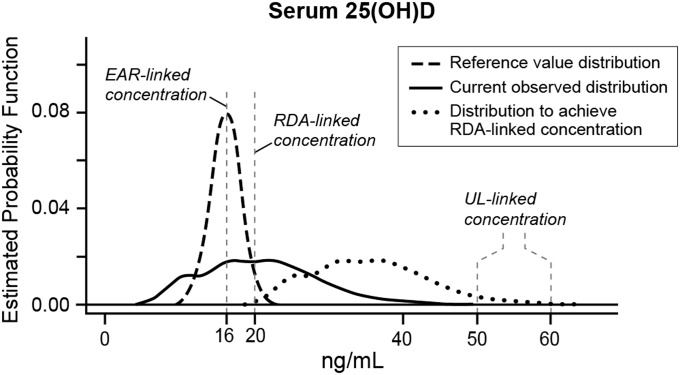

This misapplication of the RDA value is not unique to this research group (5), and clearly it is tempting to use the RDA-associated serum concentration as the goal to ensure adequacy for nearly all. This approach, however, is not only inconsistent with the Institute of Medicine–recommended methodology that considers the variability in requirements within a population, it also increases the possibility of adverse effects if it results in a proportion of the population’s intakes above the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL). To illustrate this possibility, data published elsewhere for adults aged 19–70 y from NHANES 2005–2006 (6) are shown in Figure 1, which includes the DRI-established requirement distribution for serum 25(OH)D (dashed line) and the current observed serum 25(OH)D distribution for adults aged 19–70 y (solid line). Also shown in Figure 1 is the effect of shifting the current observed distribution so that all but 2.5% achieve the RDA-associated concentration (dotted line, without adjustment for a potential nonlinear relation between intake and serum increases). Some members of the population are likely to exceed the UL. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations approaching the UL may be of particular concern for African Americans. A recent publication (7) confirmed a reverse J-shaped association between 25(OH)D and all-cause mortality for NHANES participants and also showed an increased risk of mortality in non-Hispanic blacks that exceeded that for non-Hispanic whites at serum 25(OH)D concentrations of 40–47.6 ng/mL (RR: 2.1 in blacks compared with 1.1 in whites) and at ≥48 ng/mL (RR: 2.4 for blacks compared with 1.6 for whites; referent is 30–39.6 ng/mL). Although these risk estimates may not differ statistically (likely reflecting the small sample size of non-Hispanic blacks), the point estimates suggest a basis for concern for greatly increased serum 25(OH)D concentrations among this population group.

FIGURE 1.

Serum 25(OH)D reference distribution with a comparison of observed serum 25(OH)D concentrations for adults aged 19–70 y in NHANES 2005–2006 (n = 3871) with the observed distribution shifted so that 97.5% of the sample achieve 20 ng/mL. The reference distribution was derived by using the mean (95th percentile) specified by the Institute of Medicine (2) with a calculated SD = 5.0 nmol/L on the basis of normality. The estimated probability function indicates the frequency of each concentration in the sample. Modified from reference 6 and reproduced with permission from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; RDA, Recommended Dietary Allowance; UL, Tolerable Upper Level; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

In addition, we note that Ng et al (1) did not take into account another key component in the setting of DRIs. That is, the nutrient dose-response relation must reflect the total exposure rather than an added exposure superimposed on an undefined underlying exposure. Their study as designed focused only on the contribution from the supplements administered; it failed to account for the “background” intake from dietary sources. Background vitamin D intake is not insignificant [estimated at 200–428 IU/d for age groups ≥1 y (6)] and, importantly, baseline vitamin D intake appears to alter the dose-response relation (8).

Finally, in considering the issues raised by Ng et al (1), it is important to keep in mind that African Americans are an understudied population group for whom target serum concentrations of vitamin D are unclear, especially because the DRI was established on the basis of bone health, for which African Americans have an advantage relative to white populations (9). Furthermore, as shown by the recent report from Powe et al (10) concerning vitamin D binding protein among blacks, they may also experience genetic variation and other differences relative to the metabolism or bioavailability of vitamin D that have not been clearly elucidated. More research is needed in this population to discern vitamin D requirements; in the meantime, available research should at least appropriately apply the DRI constructs, and include contributions of diet, to build this literature.

Acknowledgments

The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ng K, Scott JB, Drake BF, Chan AT, Hollis BW, Chandler PD, Bennett GG, Giovannucci EL, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Dose response to vitamin D supplementation in African Americans: results of a 4-arm, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:587–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: applications in dietary assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: applications in dietary planning. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SP, Barr SI. Practice paper of the American Dietetic Association: using the Dietary Reference Intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:762–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trumbo PR, Barr SI, Murphy SP, Yates AA. Dietary Reference Intakes: cases of appropriate and inappropriate uses. Nutr Rev 2013;71:657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CL, Carriquiry AL, Bailey RL, Sempos CT, Yetley EA. Appropriateness of the probability approach with a nutrient status biomarker to assess population inadequacy: a study using vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:72–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sempos CT, Druazo-Arvizu RA, Dawson-Hughes B, Yetley EA, Looker AC, Schleicher RL, Cao G, Burt V, Kramer H, Bailey RL, et al. Is there a reverse J-shaped association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and all-cause mortality? Results from the U.S. nationally representative NHANES. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, Miller PD, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, Tamez H, Zhang D, Bhan I, Karumanchi A, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]