Abstract

Although the importance of mast cells (MCs) in response to allergens has been characterized extensively, the contribution of these cells in host defense against bacterial pathogens is not well understood. Previously, we have demonstrated that the release of interleukin-4 by bone marrow-derived MCs inhibits intramacrophage replication of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS). Because pneumonic tularemia is one of the several manifestations of infection by Francisella, it is important to determine whether MCs present in mucosal tissues, i.e. the lung, exhibit similar effects on LVS replication. On the basis of this rationale, we phenotypically compared mucosal mast cells (MMCs) to traditional bone marrow-derived MCs. Both cell types exhibited similar levels of cell surface expression of fragment crystal epsilon receptor I (FcεRI), mast/ stem cell growth factor receptor (c-Kit) and major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI), as well as patterns of granulation. MMCs exhibited a comparable, but somewhat greater uptake of fluorescent-labeled beads compared with MCs, suggesting an increased phagocytic ability. MCs and MMCs co-cultured with primary macrophages exhibited comparable significant decreases in LVS replication compared with macrophages cultured alone. Collectively, these results suggest that MMCs are phenotypically similar to MCs and appear equally effective in the control of intramacrophage F. tularensis LVS replication.

Keywords: mast cell, mucosal mast cell, intramacrophage replication, Francisella tularensis

Introduction

Mast cells (MCs) have historically been considered to be relevant participants in allergic reactions due to prominent expression of IgE and release of histamine.1 Furthermore, there is increasing evidence for the role of these cells in host defenses against invasive pathogens due to the prominence of MCs at mucosal sites and respective effector functions.2 The role of MCs in detection and initiation of early responses to various Gram-negative bacteria is clear from studies detailing (1) increased mortality in MC-deficient mice challenged with Escherichia coli;3 (2) the role of tissue-specific MCs in clearance of E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa;3–5 and (3) the necessity of MCs for host survival via recruitment of neutrophils in response to toxins released by Clostridium difficile.6 Thus, studies involving both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria provide a basis for examining further the role of MCs in controlling bacterial infection.

Following synthesis in the bone marrow, MCs localize to areas including the skin, peritoneum and mucosal tissues, where specialized characteristics are acquired based on the presence of specific proteins in the environmental milieu.7 Differentiated MCs are targeted to their final location based on expression of specific cell surface integrins, i.e. α4β7 in the case of mucosal mast cells (MMCs).7 Moreover, these MCs can be characterized based on tissue-specific granulation patterns.2 Subsequent to MC activation, a complex set of mediators is released, including granule-stored leukotrienes, prostaglandins, cytokines and chemokines.8 MC plasticity is an important feature for adapting to differential environmental cues, as highlighted in experiments of Heib et al.,7 who demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of MCs resulted in the cells acquiring functionalities of cells comprising a specific tissue.7

We have developed an interest in using the Gram-negative facultative intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis as a model organism for elucidating MC function in limiting bacterial infection. We have shown the role of MCs in controlling intracellular replication of F. tularensis in macrophages (the preferential host cell) via release of the cytokine interleukin (IL)-4 and contact-dependent mech-anisms.9 Additional findings from our laboratory indicate that the P815 MC line, which lacks the fragment crystal epsilon receptor I (FcεRI), exhibits a similar degree of control of bacterial replication in J774A.1 macrophages.10 Subsequently, we demonstrated that MC-secreted IL-4 reduces intramacrophage replication by increasing ATP production and phagolysosome acidification, ultimately creating a hostile environment unfavorable for F. tularensis survival.11 Because MCs have historically served as a heterogeneous model of MMCs,7 we sought to directly compare MMCs and MCs in the ability to control F. tularensis intramacrophage replication.

Methods

Mice

All experiments were performed utilizing six-week-old specific pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Frederick, MD, USA). All experiments were performed following approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Bacteria

The live vaccine strain (LVS) strain of F. tularensis was obtained from Dr R Lyons, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA (lot 703-0303-016) and grown in trypticase soy broth supplemented with cysteine.

Primary cell generation

Bone marrow cells collected from mouse femurs were grown overnight in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium-containing spent L929 cell supernatant. Adherent cells were maintained in the above media for derivation of macrophages. MCs and MMCs were derived separately from non-adherent cells using different cytokine cocktails. MCs were derived utilizing IL-3 and stem cell factor (SCF) (PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA).9 MMCs were generated by maintaining non-adherent cells with IL-3, SCF, IL-9 and TGF-β (PeproTech) as described by Miller et al.12

In vitro cellular infection

Populations of MCs alone and in co-cultures with macrophages were infected with 100 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of F. tularensis LVS as previously described by Ketavarapu et al.9

Flow cytometric detection of surface marker expression

Cytometric detection of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated c-Kit and FCεRI and phycoerythrin-conjugated major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI) surface markers (all obtained from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) on MCs and MMCs were carried out as previously described using appropriate isotype controls.11 FACSCalibur data were analyzed using CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Fluorescent bead assay

Uptake of fluorescent beads by MCs and MMCs was determined as described previously by Ray et al.,13 except that only mouse cells and rat anti-mouse c-Kit FITC were used for cellular staining.

Staining of MC granules

Wright's staining (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) of MCs and MMCs was carried out as outlined by Thathiah et al.10

Statistics

Student's t-test was used for analysis of bead phagocytosis and LVS replication data. All data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments analyzed independently.

Results

Because MCs and MMCs were differentiated separately over a five-week period using distinct cytokine cocktails from different publications, we examined expression of established MC surface markers on each population at weekly intervals by flow cytometry (Table 1). Cells were stained for expression of FcεRI, c-Kit and MHCI. FcεRI is a MC membrane receptor specific for IgE which is particularly germane to allergic reactions, c-Kit is the MC SCF receptor and MHCI is present in high quantities on the MC membrane upon IL-3 and SCF stimulation.11 To demonstrate the overall prevalence of relevant surface markers, the mean fluorescence intensity for both cell types has been included in Table 1. The purity of the individual cell populations was high (<95%), with other cells such as macrophages present in low numbers, as indicated by staining with the macrophage marker CD11b. Throughout culturing, MCs and MMCs exhibited increased expression of the screened surface markers, indicating further maturation with continued cytokine exposure.

Table 1. Mast cells (MCs) and mucosal mast cells (MMCs) exhibit similar maturation profiles despite differential cell culture conditions*.

| % Cells expressing surface marker/mean fluorescence intensity† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Week 2 | Week 5 | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Cell type | c-Kit | FcεRI | MHCI | c-Kit | FcεRI | MHCI |

| MCs | 44/49 | 38/244 | 53/82 | 80/180 | 88/26 | 98/78 |

| MMCs | 45/59 | 32/360 | 78/84 | 96/170 | 92/28 | 99/87 |

FcεRI, fragment crystal epsilon receptor I; MHCI, major histocompatibility complex I

Data from weeks 2 and 5 are shown to demonstrate ultimate maturation profiles. Results are representative of two independent experiments

Mean fluorescence intensity represents the average output of each fluorophore for the total events acquired

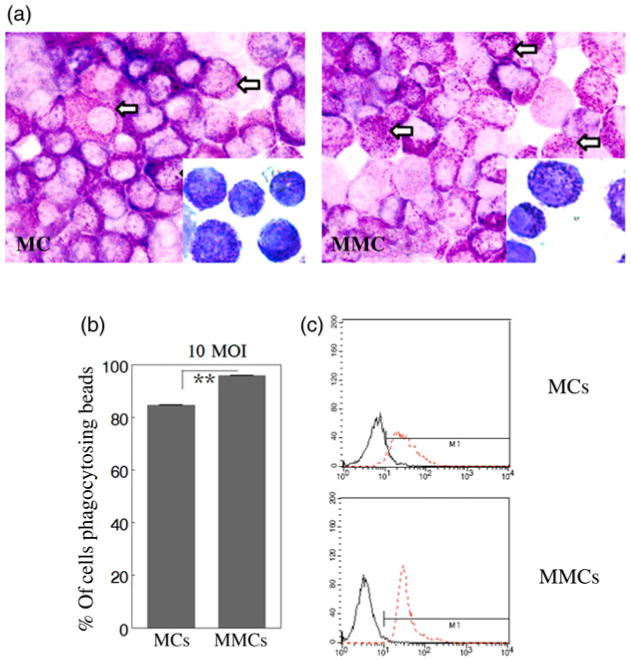

Wright staining was performed on each MC culture after approximately four weeks of maturation to qualitatively characterize MC and MMC populations (representative images in Figure 1a). Both cell populations exhibited characteristic patterns with nuclei staining blue with large, deeply purple-stained basophilic granules visible inside the cells and a lighter purple-stained cytoplasm. External granules were also visible, indicating degranulation occurring in some MCs and MMCs. To determine possible differences in phagocytic activity, MCs and MMCs were incubated with fluorescent beads of approximately the same size as Francisella, with the expectation of comparable uptake patterns, at concentrations of 10 or 100 beads/cell for 2 h and analyzed for uptake by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1b, both MCs and MMCs exhibited a similar, although significantly different (P < 0.05), gross capacity for uptake of labeled beads with MCs less than that observed for MMCs (85% and 95%, respectively). This numerical difference in bead uptake between populations was further illustrated by the histograms in Figure 1c, which compares the 10 beads/cell experimental data to control cells containing no beads. The 100 beads/cell condition (data not shown) appears to represent a situation of large bead excess, as the respective histograms for both cell populations were found to overlay those exposed to 10 beads/cell.

Figure 1.

(a) Mast cells (MCs) and mucosal mast cells (MMCs) exhibit similar morphology and granulation patterns. Wright's stain was utilized to examine morphology and visualize the presence of granules in MCs and MMCs by brightfield microscopy at 400× final magnification with 1000× final magnification inserts. White arrows indicate basophilic granules. (b) Comparison of phagocytic bead uptake of MCs and MMCs. The values are statistically different but similar. MCs and MMCs were cultured with fluorescent beads at 10 or 100 beads/cell for 2 h and then analyzed by flow cytometry to measure capacity for bead uptake. Only data for 10 beads/cell are shown. Bars represent the population of cells positive for bead uptake. Unpaired t-test **P < 0.05. (c) Histograms are shown to indicate MC and MMC bead uptake at 10 beads/cell (red dotted line) compared with control sample containing no beads (solid black line). The MMCs appear more likely to uptake multiple beads, while the larger distribution of the MC population suggests variability in uptake. Results are representative of one experiment performed in triplicate, with 10,000 events acquired per trial

Given the comparable phagocytic activity of MCs and MMCs, we sought to determine whether these cells exhibited a similar trend with regard to controlling intramacrophage replication of F. tularensis. MCs and MMCs alone, or in co-culture with bone marrow-derived macrophages, were infected with an excess of LVS (100 MOI). As shown in Figure 2, a marked three-log (1000-fold) increase in replication within infected macrophages was observed between 3 and 24 h. In contrast, significantly (P < 0.05) less bacterial replication within MCs, MMCs and in co-cultures after 24 h was observed when compared with LVS-infected macrophages, although the initial amount of LVS uptaken by each MC type was similar to macrophages alone at 3 h. When co-cultured with MCs and MMCs, macrophages exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) decreased (∼2.5 log) LVS replication at 24 h compared with macrophages cultured alone. Collectively, these results support the theme that MMCs are as effective as MCs in controlling intramacrophage F. tularensis replication.

Figure 2.

Mast cells (MCs) and mucosal mast cells (MMCs) similarly inhibit intramacrophage replication of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) in vitro. Macrophages (Macs), MCs and MMCs, or co-cultures at a total density of 5 × 105 cells/well were infected with LVS (multiplicity of infection = 100) for 2 h, treated with gentamicin for an additional 1 h, then lysed or cultured in fresh media. Lysates were dilution plated for bacterial enumeration at 3 and 24 h post-infection. Unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05. Results are representative of two independent experiments

Discussion

MCs have historically been utilized as a heterogeneous culture model of MMC-like cells. While both MCs and MMCs are derived from hematopoietic stem cell precursors, exposure to environmental factors at the ultimate target site may influence specific characteristics of each cell type.14 Although the differentiation mechanism remains to be elucidated, the bone marrow used to generate MMCs likely gives rise to many common characteristics of MCs and MMCs observed in this study. FcεRI and c-Kit are defined MC surface markers, while the appearance of the MHCI marker has been attributed to stimulation with IL-3 and SCF.1 MC plasticity is highlighted by the ability of these cells to adapt phenotypically to unfamiliar environmental cues.7 Furthermore, the presence of IL-9, a potent stimulator of MC proliferation,12 may account for the increased number of cells in the MMC culture compared with the MC culture (C Hunter & B Arulanandam, unpublished observations).

Owing to localization at mucosal interfaces where contact with foreign pathogens would be likely, MMCs may be slightly more efficient at phagocytosis,14 as observed in this study. MMCs appeared to exhibit a greater bead uptake response, evidenced by the sharp histogram peak of high intensity in contrast with the more variable range of phagocytic activity exhibited by MCs possibly indicating uptake of fewer beads based on the broader but less intense histogram (Figure 1c). To support this, we microscopically counted the fluorescent beads and noticed an ∼2-fold increase in internally visible beads in MMCs versus MCs (data not shown), although this difference may not be physiologically important.

We have previously demonstrated that MCs are able to amplify the immune response of other innate immune cells to bacterial pathogens.9,10 In spite of the excess of LVS, only portions of bacteria were taken up by the MCs in this study. However, this level of infection, sufficient for IL-4 production, repressed intramacrophage replication of Francisella in co-culture with MCs or MMCs.9 The degree of LVS replication in MCs, MMCs, macrophages and co-cultures is consistent with our previously published work.9–11 Similar results have also been observed with a non-FCεRI-bearing P815 MC line in co-culture with the J774A.1 macrophage cell line.10 More specifically, secretion of IL-4 and contact-dependent mechanisms have been shown to inhibit intramacrophage replication and apoptosis associated with increased ATP production and phagosomal acidification in macrophages.11 We have now provided evidence that MMCs, like MCs, exhibit a similar capacity to control intramacrophage LVS replication.

Acknowledgments

This research has been performed with funding provided by the NIH (Grant P01 AI057986) and the Army Research Office of the Department of Defense under Contract No. W911NF-11-1-0136.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors participated in the design, interpretations of the studies, analysis of the data and review of the manuscript. CH, MNG and BA wrote the manuscript; CH and AR performed the experiments; CH, AR and J-JY analyzed the data; J-JY, JC and MNG provided technical expertise; BA designed the experiments; and MNG, JC and BA edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Frossi B, De Carli M, Pucillo C. The mast cell: an antenna of the microenvironment that directs the immune response. J Leukocyte Biol. 2004;75:579–85. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kneilling M, Rocken M. Mast cells: novel clinical perspectives from recent insights. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:488–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malaviya R, Ikeda T, Ross E, Abraham SN. Mast cell modulation of neutrophil influx and bacterial clearance at sites of infection through TNF-α. Nature. 1996;381:77–80. doi: 10.1038/381077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland RE, Olsen JS, McKinstry A, Villalta SA, Wolters PJ. Mast cell IL-6 improves survival from Klebsiella pneumoniae and sepsis by enhancing neutrophil killing. J Immunol. 2008;181:5598–605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siebenhaar F, Syska W, Weller K, Magerl M, Zuberbier T, Metz M, Maurer M. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa skin infections in mice is mast cell-dependent. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1910–6. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wershil BK, Castagliuolo I, Pothoulakis C. Direct evidence of mast cell involvement in Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced enteritis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:956–64. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heib V, Becker M, Taube C, Stassen M. Advances in the understanding of mast cell function. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:683–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall J, Jawdat D. Mast cells in innate immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ketavarapu J, Rodriguez A, Yu J, Cong Y, Murthy A, Forsthuber T, Guentzel M, Klose K, Berton M, Arulanandam B. Mast cells inhibit intramacrophage Francisella tularensis replication via contact and secreted products including IL-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9313–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707636105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thathiah P, Sanapala S, Rodriguez A, Yu J, Murthy A, Guentzel M, Forsthuber T, Chambers J, Arulanandam B. Non-FcεR bearing mast cells secrete sufficient interleukin-4 to control Francisella tularensis replication within macrophages. Cytokine. 2011;55:211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez A, Yu J, Murthy A, Guentzel M, Klose K, Forsthuber T, Chambers J, Berton M, Arulanandam B. Mast cell/IL-4 control of Francisella tularensis replication and host cell death is associated with increased ATP production and phagosomal acidification. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:217–26. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller H, Wright S, Knight P, Thornton E. A novel function for transforming growth factor- β1: upregulation of the expression and the IgE-independent extracellular release of a mucosal mast cell granule-specific β-chymase, mouse mast cell protease-1. Blood. 1999;93:3473–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray H, Chu P, Wu T, Lyons C, Murthy A, Guentzel M, Klose K, Arulanandam B. The Fischer 344 Rat reflects human susceptibility to Francisella pulmonary challenge and provides a new platform for virulence and protection studies. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bischoff SC. Physiological and pathophysiological functions of intestinal mast cells. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:185–205s. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]