To the Editor:

If 80+ year-old healthy individuals are asked to memorize a list of words, the mean performance is expected to be substantially lower than the mean performance of healthy individuals who are 50–60 years old1. This effect has been repeatedly detected innumerous cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations (for a review see2) and is thought to reflect a fundamental age-related decline of memory capacity. Are all individuals prone to this aging effect? Are there some who are likely to have avoided it? If so, what are the factors that contribute to their resilience? These are the questions addressed by the Northwestern University SuperAging Study.

The first step was to identify a subset of individuals at or above the age of 80 who are most likely to have avoided age-related involutional changes of memory. To this end, we recruited healthy seniors 80 years and older whose performance on the delayed recall portion of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT Delay) was at or above the average normative values for individuals in the 56–66 year range1. We further required performance on non-memory tasks such as the 30-item Boston Naming Test (BNT-30), the Trail-Making Test Part B (TMT Part B), and Category Fluency (“Animals”) to be within or above one standard deviation of the average range for 80 year-olds according to published age-and-demographically-adjusted norms3–5. We designated these carefully selected individuals as “SuperAgers”.

Initial investigations showed that SuperAgers have distinct genetic, anatomic, and histopathologic markers 6. In specific, they did not show the common pattern of age-related atrophy in the cerebral cortex, they had a lower frequency of the e4 allele of apolipoprotein E and their brains showed fewer markers of Alzheimer pathology6, 7. In this letter, we report preliminary longitudinal neuropsychological performance of 18 community-dwelling SuperAgers (mean age 82.2±2.4 years) at baseline and at 18-month follow-up. The purpose was to determine whether the performance parameters that qualified them as SuperAgers could be maintained during this relatively short interval.

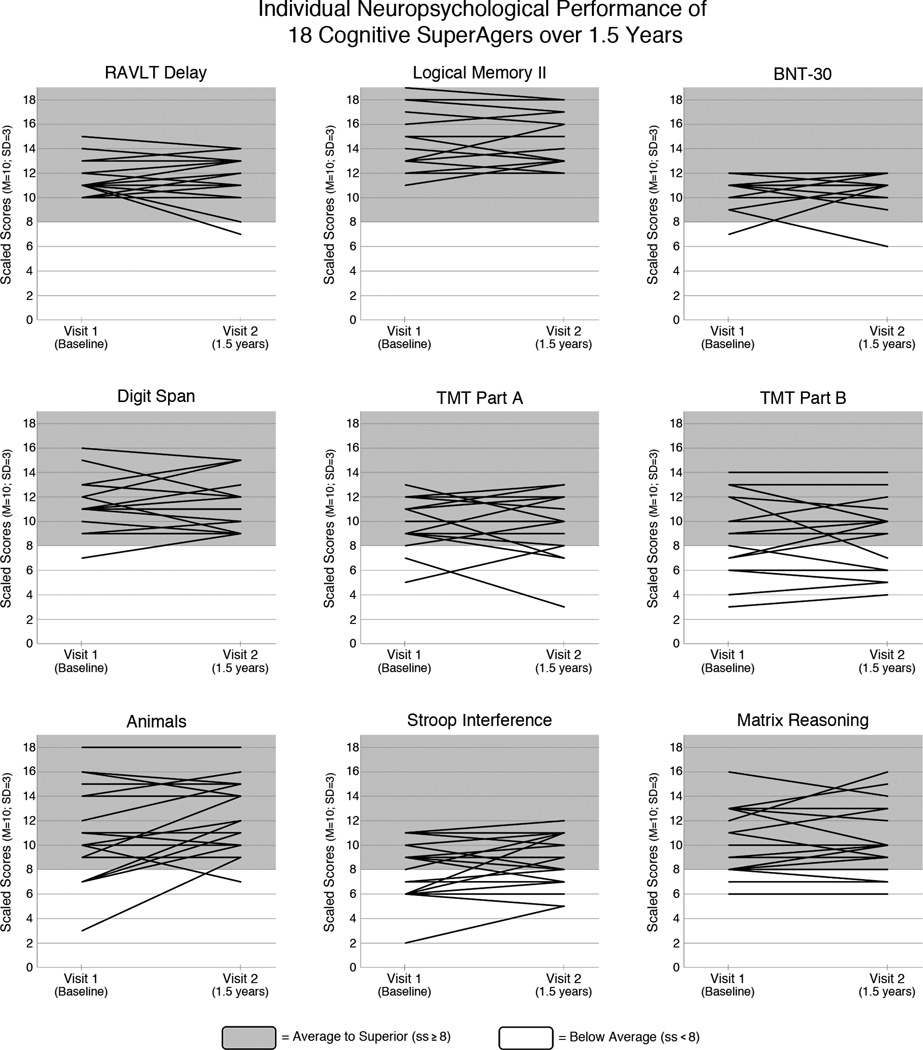

Paired t-tests were used to determine stability of longitudinal cognitive performance on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery of tests administered. On average, SuperAgers did not show significant decline on any neuropsychological measure of memory, attention, language, or executive function from baseline to 18-months (p>0.05 for each test, see Figure 1 for individual performance on each test), suggesting they maintained as a group stable cognitive performance in both memory and non-memory domains.

Figure 1.

Individual neuropsychological performance scores for all measures are shown at baseline and at 18-month follow-up. Raw scores were converted to scaled scores (ss; mean = 10; standard deviation = 3) based on normative values for individuals in their 50s and 60s1, 3–5, 9–11. Shading indicates performance levels (when converted to scaled scores based on younger norms) of above average (grey, scaled score ≥8) or below average (white, scale score <8). Spaghetti plots demonstrate that the majority of SuperAgers demonstrate generally intact cognitive scores after an 18-month period when using younger norms. Note: Memory tasks include the RAVLT Delayed Recall portion and Logical Memory II subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-III; language tasks include the 30-item Boston Naming Test (“BNT-30”), and Category Fluency (“Animals”); measures of attention include the Digit Span subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III, and the Trail-Making Test Part-A (“TMT Part A”); and measures of executive functioning include the interference subtest of the Stroop task (“Stroop Interference”), the Trail-Making Test Part-B (“TMT Part B”), and the Matrix Reasoning (“Matrix Reasoning”) subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III.

While several studies of successful aging exist8, none have prospectively followed elderly individuals defined on the basis of the stringent criterion that we applied to SuperAgers, namely an episodic memory performance at a level that would be deemed “normal” for individuals 20–30 years younger. Two possibilities need to be considered. One is that SuperAgers were at a much higher level of performance when 50–60 years old and that the current scores are compatible with customary age-related declines. The second, and more interesting possibility, is that SuperAgers are resistant to age-related cognitive decline. Our findings provide initial support for the second possibility, suggesting that SuperAgers may represent a different and unusually benign trajectory of cognitive aging. Confirmation of this possibility will be based on showing stability over longer periods of time, and especially on the demonstration that rate of change in cognition is slower than what is seen in cognitively average individuals of the same age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Sources: This project was supported by a grant from the American Psychological Foundation, The Davee Foundation, the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG13854), an NRSA fellowship from the National Institute on Aging (F31-AG043270-01), and an Early Investigator Grant from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Fund, Illinois Department of Public Health.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: Tamar Gefen, Sandra Weintraub, and Emily Rogalski contributed to the study conceptualization and design. Tamar Gefen, Emily Shaw, John Stratton, Adam Martersteck, Kristen Whitney, and Emily Rogalski contributed to the acquisition of data and generation of images. Tamar Gefen, John Stratton, Sandra Weintraub, Marsel Mesulam, and Emily Rogalski analyzed and interpreted data. Alfred Rademaker provided consultation for statistical analysis. Tamar Gefen, Sandra Weintraub, Marsel Mesulam, and Emily Rogalski edited and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and data accuracy. Emily Rogalski, Sandra Weintraub, and Marsel Mesulam supervised the study from initiation to completion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt M. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedden T, Gabrieli JD. Insights into the ageing mind: A view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:87–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE, et al. Neuropsychological tests' norms above age 55: COWAT, BNT, MAE token, WRAT-R reading, AMNART, STROOP, TMT, and JLO. Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;10:262–278. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heaton R, Miller S, Taylor M, et al. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Adjusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirk SD, Mitchell MB, Shaughnessy LW, et al. A web-based normative calculator for the uniform data set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:32. doi: 10.1186/alzrt94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogalski EJ, Gefen T, Shi J, et al. Youthful memory capacity in old brains: Anatomic and genetic clues from the Northwestern SuperAging Project. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25:29–36. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison TM, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, et al. Superior memory and higher cortical volumes in unusually successful cognitive aging. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18:1081–1085. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsler DW. Memory Scale—Third edition. Administration and scoring manual. USA: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wechsler DW. Adult Intelligence Scale—Third edition. Administration and scoring manual. USA: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden C. Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses. Chicago: Skoelting; 1978. [Google Scholar]