Abstract

Objectives

In this study, Increasing Viral Testing in the Emergency Department (InVITED), the authors investigated if a brief intervention about human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) risk-taking behaviors and drug use and misuse in addition to a self-administered risk assessment, as compared to a self-administered risk assessment alone, increased uptake of combined screening for HIV and HCV, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and beliefs and opinions on HIV/HCV screening.

Methods

InVITED was a randomized, controlled trial conducted at two urban emergency departments (EDs) from February 2011 to March 2012. ED patients who self-reported drug use within the past three months were invited to enroll. Drug misuse severity and need for a brief or more intensive intervention was assessed using the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two study arms: a self-administered HIV/HCV risk assessment alone (control arm), or the assessment plus a brief intervention about their drug misuse and screening for HIV/HCV (intervention arm). Beliefs on the value of combined HIV/HCV screening, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions on HIV/HCV screening in the ED were measured in both study arms before the HIV/HCV risk assessment (pre), after the assessment in the control arm, and after the brief intervention in the intervention arm (post). Participants in both study arms were offered free combined rapid HIV/HCV screening. Uptake of screening was compared by study arm. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate factors related to uptake of screening.

Results

Of the 395 participants in the study, the median age was 28 years (IQR 23 to 38 years), 44.8% were female, 82.3% had ever been tested for HIV, and 67.3% had ever been tested for HCV. Uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening was nearly identical by study arm (64.5% vs. 65.2%; Δ = −0.7%; 95% CI = −10.1% to 8.7%). Of the 256 screened, none had reactive HIV antibody tests, but seven (2.7%) had reactive HCV antibody tests. Multivariable logistic regression analysis results indicated that uptake of screening was not related to study arm assignment, total ASSIST drug scores, need for an intervention for drug misuse, or HIV/HCV sexual risk assessment scores. However, uptake of screening was greater among participants who indicated placing a higher value on combined rapid HIV/HCV screening for themselves and all ED patients, and those with higher levels of perceived HIV/HCV risk. Uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening was not related to changes in beliefs regarding the value of combined HIV/HCV screening or self-perceived HIV/HCV risk (post- vs. pre-risk assessment with or without a brief intervention). Opinions regarding the ED as a venue for combined rapid HIV/HCV screening were not related to uptake of screening.

Conclusions

Uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening is high and considered valuable among drug using and misusing ED patients with little concern about the ED as a screening venue. The brief intervention investigated in this study does not appear to change beliefs regarding screening, self-perceived risk, or uptake of screening for HIV/HCV in this population. Initial beliefs regarding the value of screening and self-perceived risk for these infections predict uptake of screening.

INTRODUCTION

Screening recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in U.S. emergency departments (EDs) and other health care settings have been evolving in recent years. Although en masse HIV screening is recommended,1,2 a more targeted approach is currently advised for HCV. HCV screening is recommended for those born between 1945 and 1965 (“baby boomers”), and persons at higher risk for infection (e.g., current or previous injection drug use (IDU), intranasal drug use, and those infected with HIV).3–6 The need for HCV screening among the much larger population of drug users who do not inject drugs, and those who are not baby boomers, has not yet been established or fully investigated.7 Because of overlapping risk factors, potential for worsening prognosis when co-infection exists,6 and ease of testing, combined screening for HIV/HCV seems to be a logical approach, although this approach is also understudied.

Emergency departments appear to be an ideal venue to research the value of combined HIV/HCV screening among drug misusers, given the intersection of risk-taking behaviors, lack of access to regular medical care, and the high prevalence of injection and non-injection drug use and misuse among ED patients.8 To the best of our knowledge there have been no studies about combined rapid HIV/HCV screening in EDs, although there have been numerous studies about conventional and rapid HIV screening, and a few published studies about conventional HCV screening. These studies have demonstrated that HCV positivity among urban ED patients is associated with IDU and non-IDU, sexual contact with IV drug users, and a history of hepatitis B infection.9–14 In an ongoing study, Galbraith et al. recently reported preliminary findings of a high yield from HCV screening among baby boomers at their ED.15 In a two-week period, 65% of 874 baby boomers agreed to HCV screening, of whom 12% had positive tests. Because of the higher prevalence16 and mortality of HCV than HIV in the United States,17 and apparent high prevalence among some ED patients,15 more attention to screening for this infection in EDs is needed.

Although HCV screening in EDs has not yet been studied thoroughly, many techniques have been investigated to improve HIV screening uptake with mixed results, including opt-out HIV screening,18–26 financial incentives,27 ED staff or clinician-initiated testing,20,28,29 oral fluid sampling for testing,30 prevention counseling,31 and video or computer-based interventions.32–34 A common barrier to maximizing HIV screening uptake is patient self-perception of not being at risk for HIV,25,28,35–45 although self-perceived and reported vs. actual risk frequently are not congruent.46 As such, self-perception of risk might be a target for screening interventions. In fact, we observed that opt-in rapid HIV screening uptake was 55% after patients completed a self-administered risk assessment about their HIV risk behaviors, whereas in a prior study without a risk assessment, uptake of opt-in rapid HIV screening was less (39%).32,44

It is possible that adding a brief intervention to a self-administered HIV/HCV risk assessment could further increase screening uptake more than a self-administered risk assessment alone. brief interventions using motivational interviewing techniques have been successful in EDs in reducing alcohol abuse and corresponding negative consequences,47,48 and increasing ED patients' confidence in their ability to decrease their alcohol use and increase condom use with regular sexual partners.49 In other settings, brief interventions have been successful in increasing HIV screening uptake,50 increasing knowledge of HIV/HCV risk factors among patients in substance misuse treatment,51 and reducing drug use and unprotected anal sex.52 A brief intervention grounded in the health belief model,53and employing motivational interview techniques, could address self-perceived as well as reported or actual risk for these infections, affect health beliefs about the value of screening for oneself and others, and help motivate patients to assess their risk for HIV/HCV and agree to screening. Such a brief intervention especially might be more efficacious among drug using or misusing ED patients who are probably more cognizant of the possible relationship of their drug use or misuse and sexual risk-taking behaviors to their risk of HIV and HCV acquisition.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if this brief intervention plus a self-administered risk assessment results in greater combined HIV/HCV screening uptake than a self-administered risk assessment alone among drug using and misusing ED patients. The secondary aims of this research were to investigate if there are moderating or mediating factors that influence uptake of combined HIV/HCV screening, such as drug misuse severity and need for a drug misuse intervention; HIV/HCV-risk behaviors; and beliefs about the value of and opinions regarding combined HIV/HCV screening in EDs and self-perceptions of having these infections. Other goals were to examine the effect of a brief intervention on these beliefs, opinions, and self-perceptions; to learn the seroprevalence of unrecognized HIV and HCV infections in this population; and to understand patient preferences regarding HIV/HCV screening in EDs.

METHODS

Study Design

This study, Increasing Viral Testing in the ED (InVITED), was a randomized, controlled trial that evaluated a brief intervention about HIV and HCV self-perceived risk and risk-taking behaviors in conjunction with drug use and misuse. The study was conducted over a 13-month period from February 2011 through March 2012. The hospital institutional review board approved the study.

Study Setting and Population

Two urban EDs in the same hospital system in Providence, Rhode Island participated. They are affiliated with the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. The Rhode Island Hospital ED is at a Level I trauma center and has an annual patient volume of over 100,000 adult visits, and the Miriam Hospital ED is in a community hospital with an annual patient volume of > 55,000 adult visits. Among all samples submitted to this hospital system's laboratory July 2012 through June 2013 for HIV and hepatitis B/C testing, the seroprevalence was 2.9% for hepatitis B surface antigen, 5.3% for HCV antibody, and 1.3% for HIV antibody (unpublished data). Rhode Island consistently ranks as having one of the highest percentages of its citizens reporting illicit drug use, and one of the highest reported prevalences of drug dependency in the United States (9% to 13%).54

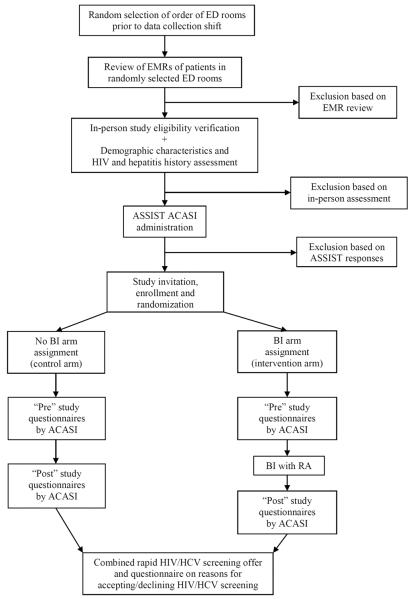

The InVITED study was performed two shifts per day (8:00 am to 4 pm, and 4 pm to midnight), seven days a week, when bilingual (English and Spanish-speaking) research assistants (RAs) could conduct the study. RAs randomly selected patients for study eligibility evaluation using an internet-based random selection program (www.random.org). Before each shift, the RA generated lists of the patient rooms in each ED in random order. The RAs first evaluated the ED electronic medical record (EMR) of patients who were selected (Figure 1). If the ED EMR review indicated that the patient was potentially eligible for the study, the RAs would ask about his or her demographic characteristics [Data Supplement 1], confirm study eligibility through a brief interview, and administer the subsequent study instruments. Patients were study eligible if they used or misused any type of drug within the prior 3 months (per the modified ASSIST survey); were 18 to 64 years old; English- or Spanish-speaking; not critically ill or injured; not prison inmates, under arrest, or undergoing home confinement; not presenting for acute psychiatric illness; not intoxicated; not known to have previous reactive HIV or HCV tests (per self-report or ED EMR mention of these infections); and not having a physical disability or mental impairment that prevented providing consent. HIV and HCV status was clarified twice: when the RAs first approached the patients, and during screening questions about history of previous testing for these infections [Data Supplement 2]. Patients were not offered incentives to participate; and ED staff members were not permitted to encourage, refer, or discourage patients to be in the study.

Figure 1. InVITED Study Flow Diagram.

EMRs = electronic medical records; ASSIST = Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; ACASI = audio computer-assisted self-interviewer; BI = brief intervention; RA = research assistant; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus

Study Protocol

Substance use or misuse was assessed using the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test, Version 3 (ASSIST).55 Per World Health Organization recommendations, an ASSIST score of four or more points for any drug category suggests a need for brief intervention, and a score of ≥ 27 points suggests a need for a more intensive intervention. Because the ASSIST was originally created as an interviewer-administered questionnaire, it does not inquire about some drug categories that are more applicable for a U.S. population, it groups some drugs into categories that have different use and misuse profiles, and based on our experience with a pilot study with the ASSIST,56 we adapted the ASSIST for an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) format and added or expanded drug categories for this study [Data Supplement 3]. We conducted standard cognitive-based assessments57–60 of the adapted ASSIST among ten English- and ten Spanish-speaking ED patients in an iterative fashion to confirm that participants comprehended the instructions, questions, and responses, and easily used the ACASI format. Cronbach's α ranged from 0.86 to 0.95 for the drug categories assessed in our adapted ASSIST.

We further queried participants about the specific drugs that they had used within the past three months and if they had been injected or prescribed [Data Supplement 3]. We also adapted for InVITED an HIV/HCV risk-taking behaviors questionnaire [Data Supplement 4] from our previous studies on HIV risk.61,62 The questionnaire asked about IV drug use and sexual behaviors by sex, according to type of sexual partner (main, casual, or exchange). We also adapted questions from our previous studies' brief questionnaires on the value of combined HIV/HCV screening (for all ED patients and for the participant), self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions on and preferences regarding HIV/HCV screening in the ED on a 0 to 4 point scale (e.g., no risk to very much at risk) [Data Supplement 5].32,63

If not previously translated, the questionnaires were translated from English into Spanish then back-translated into English using accepted techniques,64–67 and were reviewed by Spanish-speaking members of the research staff to ensure translation accuracy. The reading level of all questionnaires in English was at a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 6.2 (Microsoft Word) and the reading level of the questionnaires in Spanish was at a Huerta Reading Ease score of 80, indicating an easy level of difficulty.68 Participants completed the questionnaires in approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

InVITED Study Protocol

The RAs first queried patients about their demographic characteristics using instruments developed for and used in previous studies,44 as well as their history of HIV, HCV, and hepatitis B testing and hepatitis B vaccination (Figure 1). Those who stated that they never had a reactive HIV or HCV test were asked to continue with screening for study eligibility. Patients who reported drug use within the past three months through the ASSIST were invited to enter the randomized, controlled trial. Patients were informed during the consent process that they were being asked to enter a randomized, controlled trial regarding reducing their drug use and misuse and its relationship to HIV and HCV, but were not informed that they later would be offered combined rapid HIV/HCV screening. Participants also were informed that we had obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to prevent the researchers from being forced to disclose information about participant drug use and misuse.

After consent was obtained, participants were randomly assigned using block randomization to one of two study arms: HIV/HCV risk assessment alone (control arm), or brief intervention plus HIV/HCV risk assessment (intervention arm). After enrollment, participants in both arms completed the study (“pre”) questionnaires (the value of combined HIV/HCV screening, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening questionnaires [Data Supplement 5]), followed by the HIV/HCV risk assessment (Data Supplement 4). Participants randomly assigned to the control study arm then repeated the study (“post”) questionnaires [Data Supplement 5]. Those assigned to the intervention arm underwent the brief intervention [Data Supplement 6] and then completed the same “post” questionnaires [Data Supplement 5]. Participants completed the questionnaires confidentially using ACASI on a tablet personal computer. The RAs were blinded to the questionnaire responses.

Following the study “post” questionnaires, the RA offered participants in both study arms free rapid HIV and HCV screening (opt-in; Data Supplement 7). The main reason for accepting or declining screening was recorded, as well as patient preferences regarding HIV/HCV screening in the ED. At the end of the study encounter in the ED, the RAs provided all study participants with a brochure of local drug misuse resources and services and a brochure about HIV and HCV on how to minimize infection risk, and offered them an opportunity to discuss and how to obtain services to reduce their drug misuse.

Description of the Brief Intervention

The primary goal of the brief intervention was to motivate participants to consent to rapid testing for HIV and HCV. A brief outline of the brief intervention content is in Data Supplement 6. The brief intervention sessions were approximately 20 to 30 minutes in duration and were based on two theoretically driven approaches to behavior change: motivational interview,69 and the health belief model.53 During the brief intervention the RAs often took on the role of health educators by providing participants with information about potential exposure risks for HIV/HCV they might have encountered, and also about the importance of screening for these infections. These educational components reflected the core tenets of the health belief model of increasing perceived risk for HIV/HCV, severity of consequences of these infections, benefits of prevention behavior and testing, and self-efficacy to engage in prevention behavior.70,71 The RAs used motivational interview techniques (e.g. decisional balance, discussing goals and values)72 to facilitate a discussion about behavior changes that participants were motivated to engage in that could reduce risks for HIV and HCV, as well as improve their physical and emotional well-being. Chief topics discussed that could achieve these goals included reducing or stopping substance use, increasing use of safer sexual behaviors, requiring sexual partners to engage in safer sexual behaviors, and engaging in substance abuse treatment.

Prior to the study onset, the RAs underwent motivational interview training by a certified trainer as well as training on delivery of the brief intervention according to the study protocol. The RAs each had over 50 hours of mock brief intervention practice prior to engaging participants in the study. In addition, the RAs were certified by the state as HIV and HCV prevention counselors, had training in rapid HIV and HCV testing techniques, practiced the study protocol and procedures, and underwent didactic instruction by the investigators on relevant substance misuse and HIV and HCV topics. The RAs met with the study investigators throughout the study to discuss clinical and procedural issues arising from the delivery of the brief intervention. Prior to the onset of the study, we also conducted a pilot study among 132 ED patients in which we employed the adapted ASSIST as well as the additional questions about the specific drugs they used or misused as a tool to identify 50 patients who used or misused drugs within the previous three months. Among these 50 patients, we performed a pilot randomized controlled trial of our brief intervention and evaluated uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening. We revised our brief intervention and study protocol and procedures based on our observations.

Combined rapid HIV/HCV screening

The RAs performed rapid HIV testing using the OraQuick Advance rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test and rapid HCV testing using OraQuick HCV rapid antibody test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA). Sample collection was either via fingerstick or through use of the Diff-Safe (Alpha Scientific Corporation, Malvern, PA) device if a phlebotomized sample was available. Participants were provided the results of their tests while in the ED and were offered risk reduction counseling for HIV and HCV. Participants whose rapid tests were positive underwent counseling in the ED by the RAs, had phlebotomized samples obtained for confirmatory testing, and were arranged follow-up to obtain their final test results, and to be evaluated for further as-needed care, including hepatitis A and B vaccination.

Data Analysis

We based our sample size estimate on the primary outcome of uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening. Using the results from two previous studies on rapid HIV screening in which 39.3% agreed to be screened for HIV when a risk assessment was performed, and in which 55% agreed to be screened after an ACASI-based HIV risk assessment,44 we hypothesized that among this drug misusing population there could be at least an additional 15% absolute increase (55% vs. 70%) in uptake of HIV/HCV screening among participants who undergo risk assessment plus brief intervention compared to those who undergo risk assessment alone. Based on this hypothesis, we estimated requiring a sample size of 235 per arm with 80% power, or 164 per arm for 90% power using Pearson's chi-square test with a two-sided Type I error rate of 0.05.

Based on our previous studies,61,62 we calculated an HIV/HCV sexual risk behavior score using the relevant items from the HIV/HCV risk behavior questionnaire. The score was the sum of the risk behaviors. Two points were assigned for every yes response and one point for refused to answer/don't know responses. Because the types of sexual behaviors possibly differ by sex (e.g., male-male sexual intercourse, women having sex with men who have sex with men), we calculated the sexual risk behavior scores separately by sex. The highest possible score was 58 for females and 158 for males. There were too few IDUs to calculate a comparable score for IDU HIV/HCV risk behaviors.

Study eligibility assessments and enrollment were summarized using the recommended CONSORT approach for randomized, controlled trials.73 Participant demographic characteristics and HIV, hepatitis B, and HCV testing history were summarized (median and interquartile range [IQR], or proportions) and then compared by study arm using Wilcoxon's test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. ASSIST scores (mean, standard error) by substance category, for all drug categories combined, and for all substances combined were calculated by study arm and compared using Student's t-test. Specific drugs that participants reported using in the past three months, and responses to the HIV/HCV risk-taking behavior questionnaire, were summarized by study arm. For these and all other analyses, a two-sided α = 0.05 level of significance was used.

For the primary outcome, uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening by study arm and differences across study arms were calculated along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In secondary analyses, separate multivariable logistic regression models were created using uptake of screening as the outcome and study arm, total drug ASSIST score, and HIV/HCV sexual risk score as covariates adjusting for demographic characteristics, HIV/HCV testing history, and study RA. Additional multivariable logistic regression models were created using uptake of screening as the outcome and pre-, post-, and post-pre change (Δ) in responses to the combined HIV/HCV screening, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening questionnaires as covariates, adjusting for demographic characteristics, HIV/HCV testing history, and study RA. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% CIs were estimated. Hosmer-Lemeshow testing was used to confirm model fitness.

For the secondary objectives, responses to the value of combined HIV/HCV screening, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening questionnaires were summarized (mean and standard error pre-, post-, and post-pre Δ) by study arm, and differences in the post-pre Δs between study arms were calculated along with corresponding 95% CIs. Multivariable linear regression models were created using post-pre Δs in responses as the outcome and study arm, total drug ASSIST score, and HIV/HCV sexual risk score as covariates, adjusting for demographic characteristics, HIV/HCV testing history, and study RA. Beta coefficients (βs) with corresponding 95% CIs were estimated. Preferences regarding HIV/HCV screening were summarized by study arm and compared using Pearson's chi-square testing. All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.

RESULTS

The results of these assessments, study enrollment, and random assignments are reported in Figure 2. Commensurate with their annual ED patient volumes, 63.3% of the 395 participants were recruited at the trauma center and 36.7% at the community hospital ED. As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in the distribution of demographic characteristics and HIV and hepatitis testing histories of the 395 participants by study arm. ASSIST scores by drug categories, total ASSIST drug scores, total ASSIST scores, and the proportions of participants who would have qualified for no brief intervention, a brief intervention, or more intensive intervention by drug category (per WHO recommendations) were similar by study arm (Table 2). ASSIST drug category scores were highest for tobacco products, followed by marijuana, alcohol, prescription analgesics, cocaine or crack, and benzodiazepines. See Data Supplement 8 for further details of drug use and misuse by study arm.

Figure 2. InVITED Eligibility Assessment and Enrollment.

HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus

Table 1.

InVITED participants' demographic characteristics and HIV, hepatitis B and C testing history

| Characteristics | No Intervention n=197 | Intervention n=198 | P< |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (IQR) | 27.0 (23.0–35.0) | 28.0 (22.0–39.0) | |

| Sex | 0.80 | ||

| Female | 55.8 | 54.5 | |

| Male | 44.2 | 45.5 | |

| Ethnicity/race | 0.07 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 62.9 | 69.2 | |

| White, Hispanic | 7.6 | 6.1 | |

| Black or African American, non-Hispanic | 20.3 | 15.7 | |

| Black or African American, Hispanic | 4.6 | 8.1 | |

| Other | 4.6 | 1.0 | |

| Years of formal education | 0.27 | ||

| < 12 years | 28.4 | 26.3 | |

| Grade 12 | 27.9 | 36.4 | |

| College 1–3 years | 31.5 | 24.7 | |

| College 4 years (college graduate)/ > college | 12.2 | 12.6 | |

| Health insurance status | 0.28 | ||

| Private | 36.0 | 34.8 | |

| Governmental | 26.4 | 33.3 | |

| None | 37.6 | 31.8 | |

| Partner status | 0.81 | ||

| Married | 11.7 | 14.6 | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 12.2 | 12.6 | |

| Never married | 55.8 | 52.0 | |

| Unmarried couple | 20.3 | 20.7 | |

| Homelessness | 0.12 | ||

| Currently homeless | 7.6 | 11.1 | |

| Past 12 months homeless | 2.0 | 5.1 | |

| Never/not homeless past 12 months | 90.4 | 83.8 | |

| Employment status | 0.90 | ||

| Employed | 45.7 | 42.9 | |

| Disability | 15.7 | 17.7 | |

| Student | 11.7 | 13.1 | |

| Unemployed | 26.9 | 26.3 | |

| Usual source of medical care | 0.16 | ||

| Private clinic/practice | 33.5 | 38.9 | |

| Hospital or community health clinics | 23.9 | 27.3 | |

| ED | 35.5 | 30.8 | |

| Urgent care center | 7.1 | 3.0 | |

| Born in the United States | 0.85 | ||

| Yes | 90.9 | 91.4 | |

| No | 9.1 | 8.6 | |

| Family status | 0.49 | ||

| Never had children | 51.8 | 47.0 | |

| I have children < 17-years-old | 37.6 | 43.4 | |

| I have children ≥ 17-years-old | 10.7 | 9.6 | |

|

| |||

| Testing history | |||

|

| |||

| History of any HIV test | 0.59 | ||

| Tested, but not part of a blood donation | 37.6 | 34.8 | |

| Tested as part of a blood donation | 12.7 | 14.6 | |

| Tested and donated blood | 33.5 | 31.3 | |

| No known HIV test | 16.2 | 18.2 | |

| Don't know if ever tested | 0.0 | 1.0 | |

| History of any HBV test | 0.59 | ||

| Tested, but not part of a blood donation | 26.4 | 22.2 | |

| Tested as part of a blood donation | 23.4 | 26.8 | |

| Tested and donated blood | 22.8 | 19.2 | |

| No known HBV test | 23.9 | 28.8 | |

| Don't know if ever tested | 3.6 | 3.0 | |

| Hepatitis B vaccination | 0.80 | ||

| Yes | 49.7 | 46.5 | |

| No | 47.7 | 51.0 | |

| Don't know | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| History of any HCV test | 0.99 | ||

| Tested, but not part of a blood donation | 21.8 | 20.7 | |

| Tested as part of a blood donation | 27.9 | 26.3 | |

| Tested and donated blood | 18.3 | 19.7 | |

| No known HCV test | 28.4 | 29.3 | |

| Don't know if ever tested | 3.6 | 4.0 | |

HBV = Hepatitis B virus; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus

p values by Pearson's chi-square /Fisher's exact tests

Data are reported as percentages except where otherwise noted

Table 2.

InVITED participants ASSIST scores and WHO recommendations for an intervention by study arm

| No Intervention n=197 |

Intervention n=198 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASSIST Scores | WHO recommendations |

ASSIST Scores | WHO recommendations |

p-value (ASSIST) | |||||

| No intervention | Brief intervention | Intensive intervention | No intervention | Brief intervention | Intensive intervention | ||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Mean (SE) | % | % | % | Mean (SE) | % | % | % | p < | |

| Specific Substances | |||||||||

| Tobacco products | 12.08 (0.75) | 35.5 | 54.8 | 9.6 | 14.07 (0.77) | 29.3 | 54.5 | 16.2 | 0.56 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 8.99 (0.69) | 72.1 | 18.8 | 9.1 | 9.51 (0.71) | 66.7 | 23.2 | 10.1 | 0.56 |

| Marijuana | 11.27 (0.71) | 24.9 | 64.5 | 10.7 | 11.60 (0.70) | 25.8 | 62.6 | 11.6 | 0.56 |

| Cocaine or crack | 2.37 (0.49) | 88.8 | 8.1 | 3.0 | 2.62 (0.54) | 87.4 | 8.6 | 4.0 | 0.56 |

| Methamphetamines | 0.47 (0.16) | 97.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.45 (0.15) | 97.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Inhalants | 0.25 (0.17) | 99.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.04 (0.02) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Hallucinogens | 0.36 (0.12) | 97.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.26 (0.10) | 98.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Illicit opioids | 0.92 (0.34) | 96.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.86 (0.32) | 95.5 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.56 |

| Gamma-hydroxybutyrate | 0.05 (0.03) | 99.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.03 (0.03) | 99.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Amphetamines | 0.49 (0.19) | 96.4 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 0.33 (0.14) | 97.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Benzodiazepines | 1.44 (0.38) | 92.4 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 1.34 (0.39) | 93.4 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.56 |

| Barbiturates | 0.01 (0.01) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 (0.02) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Methadone or buprenorphine | 0.68 (0.27) | 95.9 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 0.14 (0.08) | 98.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.56 |

| Prescription opioid analgesics | 2.57 (0.45) | 82.2 | 15.7 | 2.0 | 3.00 (0.58) | 85.9 | 9.1 | 5.1 | 0.56 |

| Total ASSIST drug score | 20.87 (1.82) | 20.71 (1.59) | 0.99 | ||||||

| Total ASSIST score | 41.94 (2.58) | 44.29 (2.36) | 0.72 | ||||||

| WHO recommended interventions | 15.8 | 69.5 | 14.7 | 16.2 | 65.2 | 18.7 | 0.54 | ||

SE = Standard Error; ASSIST = Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; WHO = World Health Organization

p-values were calculated using chi-square (for specific substances ASSIST scores) and Student's t (for total ASSIST scores) tests.

Per the HIV/HCV risk behavior questionnaire responses, past three-month IDU was 1.8% in the no intervention arm and 1.9% in the intervention arm among males and 0% among females in both study arms, and none in either study arm reported sharing any injection-drug paraphernalia within the past three months. HIV/HCV sexual risk scores were: mean 10.9, median 10 (IQR 5 to 14) for women, and mean 11.8, median 12 (IQR 8 to 16) for men, in the both arms. Scores on the questionnaire were comparable between study arms (p < 0.44). Most participants reported having a main sexual partner within the past three months and/or a casual sexual partner, while few noted exchange partners. Lack of condom use was frequent, especially with main and casual partners, and more participants reported knowing that their partners had sexually transmitted diseases than having HIV or HCV. The total number of sexual partners without condom use were similar between the two study arms, yet men tended to report higher numbers of sexual partners than women. Few (2%) men reported having sex with other men, although 7.3% of women reported that they knew their male sexual partners had sex with other men. See Data Supplement 9 for further details about IDU and sexual HIV/HCV risk behaviors reported by participants.

Uptake of Combined Rapid HIV/HCV Screening

As shown in Table 3, uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening was nearly identical by study arm (64.5% vs. 65.2%; Δ = −0.7%; 95% CI = −10.1% to 8.7%). Of the 256 screened, none had reactive HIV antibody tests, but seven (2.7%; four in the intervention arm and three in the control arm) had reactive HCV antibody tests. Of these, two later revealed that they already knew they previously had reactive HCV antibody tests, which left five (2.0%) who did not previously have reactive HCV antibody tests. Of these five participants, the age range was 25 years to 41 years, all were male, four reported previous HCV testing, two reported previous or recent IDU, and none reported male-male sex. Data Supplement 10 provides further details about the HCV-reactive antibody participants.

Table 3.

Change in beliefs and opinions on HIV/HCV screening and risk and uptake of HIV/HCV screening

| Belief or Opinion | No Intervention n=197 | Intervention n=198 | Intervention - No Intervention Δ1 - Δ2 (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Pre | Post | Post - Pre Δ1 | Pre | Post | Post - Pre Δ2 | ||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | ΔMean (95% CI) | |||

| Change in value of combined HIV/HCV screening | |||||||

| Value for all | 3.36 (0.07) | 3.26 (0.07) | −0.09 (0.06) | 3.46 (0.06) | 3.40 (0.07) | − 0.06 (0.06) | 0.037 (−0.13 to 0.20) |

| Value for me | 2.54 (0.10) | 2.63 (0.10) | 0.08 (0.07) | 2.64 (0.10) | 2.72 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.09) | −0.004 (−0.23 to 0.22) |

| Change in self-perception of HIV/HCV risk | |||||||

| HIV | 0.58 (0.07) | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.77 (0.07) | 0.85 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.062 (−0.083 to 0.21) |

| HCV | 0.52 (0.06) | 0.53 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.091 (−0.055 to 0.24) |

| Change in opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening | |||||||

| ED is too stressful place for testing | 2.05 (0.08) | 1.83 (0.08) | −0.19 (0.08) | 1.95 (0.08) | 1.75 (0.07) | −0.18 (0.08) | −0.23 (−0.49 to 0.034) |

| ED is not a private enough place for testing | 2.21 (0.09) | 1.89 (0.08) | −0.29 (0.08) | 2.03 (0.09) | 1.79 (0.08) | −0.23 (0.08) | −0.048 (−0.26 to 0.17) |

| Being tested in the ED delays medical care | 2.16 (0.09) | 1.73 (0.06) | −0.45 (0.08) | 2.20 (0.08) | 1.67 (0.07) | −0.51 (0.07) | −0.001 (−0.22 to 0.22) |

| Being tested in the ED takes too long | 2.16 (0.10) | 1.76 (0.07) | −0.39 (0.09) | 2.28 (0.09) | 1.68 (0.07) | −0.62 (0.09) | 0.041 (−0.18 to 0.26) |

| % | % | Δ% (95% CD) | |||||

| Uptake of HIV/HCV screening | 64.5 | 65.2 | −0.7 (−10.1 to 8.7) | ||||

Δ= Difference; SE = Standard Error; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus

Per the results of the multivariable logistic regression analyses (Table 4), uptake of screening was not related to study arm assignment, total drug ASSIST score, HIV/HCV sexual risk score, or WHO recommendations on need for any drug misuse intervention, after adjustment for demographic characteristics, HIV/HCV testing history, or study RA. However, before (“pre”) and after (“post”) taking the HIV/HCV risk assessment (and brief intervention), uptake of screening was greater among participants who indicated placing a higher value on combined rapid HIV/HCV screening for themselves and all ED patients, and those with higher levels of perceived HIV/HCV risk (Table 4). Changes in beliefs regarding the value of combined HIV/HCV screening or self-perceived HIV risk post- vs. pre-HIV/HCV risk assessment (with or without the brief intervention) were not related to uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening. Opinions regarding the ED as a location for combined rapid HIV/HCV screening were not related to uptake of screening.

Table 4.

Relationship of beliefs, self-perception of risk and opinions on uptake of HIV/HCV screening

| Belief or Opinion | Uptake of HIV/HCV screening* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Post – Pre Difference | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Change in value of combined HIV/HCV screening | |||

| Value for all | 1.37 (1.06–1.78) | 1.30 (1.02–1.66) | 1.03 (0.77–1.39) |

| Value for me | 1.34 (1.13–1.59) | 1.40 (1.17–1.67) | 1.01 (0.82–1.23) |

| Change in self-perception of HIV/HCV risk | |||

| HIV | 1.43 (1.08–1.89) | 1.35 (1.03–1.77) | 0.91 (0.65–1.27) |

| HCV | 1.51 (1.10–2.07) | 1.34 (1.02–1.78) | 0.92 (0.64–1.31) |

| Change in opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening | |||

| ED is too stressful place for testing | 0.79 (0.63–1.00) | 0.58 (0.46–0.73) | 0.74 (0.58–0.95) |

| ED is not a private enough place for testing | 0.82 (0.67–0.99) | 0.69 (0.55–0.85) | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) |

| Being tested in the ED delays medical care | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 0.62 (0.47–0.81) | 1.00 (0.78–1.29) |

| Being tested in the ED takes too long | 0.72 (0.56–0.91) | 0.63 (0.49–0.80) | 0.90 (0.70–1.15) |

Models adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity/race, years of formal education, health insurance status, partner status, employment status, usual source of medical care, HIV and HCV testing history, and study research assistant.

HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus; OR = Odds Ratio

Beliefs on Value of, Self-perceived Risk for, and Opinions Regarding ED Rapid HIV/HCV Screening

In both study arms, prior to the risk assessment (or brief intervention), all participants placed a relatively higher value (3.4 on a 0 to 4 scale among all participants) on combined rapid HIV/HCV screening for all ED patients and to a lesser degree for themselves (2.6 on a 0 to 4 scale). Likewise, self-perceived risk among all participants for having an HIV or HCV infection was low (0.68 for HIV and 0.60 for HCV on a 0 to 4 scale). Participants in both study arms also had moderate concerns regarding the ED as a venue for combined rapid HIV/HCV screening (1.9 to 2.2 for all four questions on a 0 to 4 scale). After the risk assessment (or brief intervention), beliefs in the value of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening did not change substantially in either study arm, nor did self-perceived risk for these infections (Table 3). However, concerns regarding the ED as a venue for screening decreased in both study arms. There were no differences between the brief intervention and control study arms in regards to changes in beliefs about the value of combined HIV/HCV screening, self-perception of HIV/HCV risk, and opinions about HIV/HCV screening, post- vs. pre-HIV/HCV risk assessment (with or without the brief intervention) (Table 3). Per the results of the multivariable linear regression analyses (Table 5), change in beliefs about the value of screening, self-perceived risk for HIV/HCV, and opinions regarding the ED as a venue for screening were not related to study arm assignment, total drug ASSIST score, HIV/HCV sexual risk score, or WHO recommendations on need for any drug misuse intervention, after adjustment for demographic characteristics, HIV/HCV testing history, or study RA.

Table 5.

Relationship of beliefs, self-perception of risk opinions, and uptake of screening to study arm, ASSIST score, and HIV/HCV sexual risks

| Opinion or Belief Question | WHO recommendations* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Arm* β (95% CI) | Total Drug Score* β (95% CI) | Sex Risk Score* β (95% CI) | No intervention | Brief intervention β (95% CI) | Intensive intervention β (95% CI) | |

| Change in value of combined HIV/HCV screening | ||||||

| Value for all | 0.02 (−0.2 to 0.2) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.02) | REF | 0.13 (−0.11 to 0.19) | 0.01 (−0.30 to 0.32) |

| Value for me | 0.01 (−0.2 to 0.2) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.03) | REF | −0.41 (−0.74 to −0.08) | −0.29 (−0.72 to 0.13) |

| Change in self-perception of HIV/HCV risk | ||||||

| HIV | 0.07 (−0.08 to 0.2) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | REF | −0.03 (−0.23 to 0.18) | 0.08 (−0.19 to 0.36) |

| HCV | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.3) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.02) | REF | −0.01 (−0.23 to 0.20) | 0.06 (−0.21 to 0.34) |

| Change in opinions regarding ED-based HIV/HCV screening | ||||||

| ED is too stressful place for testing | −0.01 (−0.23 to 0.23) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | REF | −0.09 (−0.42 to −0.23) | 0.11 (−0.31 to 0.52) |

| ED is not a private enough place for testing | 0.05 (−0.18 to 0.28) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | REF | −0.08 (−0.40 to 0.25) | −0.20 (−0.61 to 0.22) |

| Being tested in the ED delays medical care | −0.05 (−0.27 to 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | REF | 0.08 (−0.24 to 0.40) | −0.13 (−0.54 to 0.27) |

| Being tested in the ED takes too long | −0.25 (−0.52 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.08) | REF | −0.02 (−0.41 to 0.36) | −0.25 (−0.73 to 0.23) |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Uptake of HIV/HCV screening | 1.08 (0.69 to 1.70) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | REF | 1.76 (0.95 to 3.28) | 2.29 (1.00 to 5.25) |

Models adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity/race, years of formal education, health insurance status, partner status, employment status, usual source of medical care, HIV and HCV testing history, and study research assistant.

β = beta; Δ = difference; ASSIST = Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus; OR = odds ratio; REF = reference; WHO = World Health Organization

Preferences Regarding HIV/HCV Screening in the ED

The most common reason for accepting combined rapid HIV/HCV screening among all participants was “Convenient to be tested now in the emergency department” (42%), and the most common reason for declining it was “Don't believe it's necessary for me/not at risk” (31%). The reasons for declining the screening did not differ by study arm (p < 0.12), but more in the intervention arm reported convenience as a reason to be tested than in the control arm (50.4% vs. 33.3%; p < 0.02). Among all participants, most (80%) preferred to be offered testing for both HIV and HCV as opposed to either being offered separately, and these preferences did not differ by study arm (p < 0.38). The most common reason of preference for testing for HIV only is “I have heard a lot about HIV” (46%), and the most common reason of preferring to be offered testing for HCV only is “I know I am not at risk for the other infection” (43%). The reasons for preferring being offered only HIV or HCV testing did not differ by study arm (HIV only, p < 0.37; HCV only, p < 0.70). Further details about acceptance or decline of testing are provided in Data Supplement 11.

DISCUSSION

The InVITED study results provide some interesting lessons regarding combined rapid HIV/HCV screening in EDs among a drug using and misusing population. First, uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening was relatively high (about 65% among all participants), and few participants had concerns about the ED as a venue for screening for these infections. Further, uptake of screening for HIV/HCV was higher than our previous opt-in rapid HIV screening among a general ED population when offered without an intervention or risk assessment (39%), and after a risk assessment with or without computer-based tailored feedback about risk-taking behaviors (55%).32,44 These findings indicate that this population is receptive to combined screening for these infections as well as this venue for screening, even in the absence of incentives. Of course, a drug misusing population might have a higher self-perception of risk, perceived need, or level of receptivity for screening for these infections than non-drug users, which cannot be determined by the results of this study. It is important to note, although from a small sample, that only two of those newly diagnosed with HCV reported IDU, and none were baby boomers or were HIV-infected men who reported male-male sex. Further study is needed to determine if HCV screening recommendations should be expanded, as has been advocated.74

Second, the strongest indicators of uptake of combined rapid HIV/HCV screening were initial beliefs about the value of this screening and self-perception of risk for these infections. Third, use of a risk assessment and the brief intervention performed in this study do not appear to be helpful in changing beliefs and opinions regarding combined HIV/HCV screening or self-perception of risk for these infections. These findings taken together suggest that among this drug misusing population, their beliefs and receptivity to screening are not affected by either the potential self-reflection of a risk assessment or a motivational interview centered around drug use/misuse and its relationship to HIV/HCV risk and the value of screening. However, it might be premature to conclude that these approaches are not useful. One limitation of the design of this study is that willingness to undergo combined rapid HIV/HCV screening could not be assessed prior to initiation of the intervention without potentially contaminating the effect of the evaluation of the brief intervention. As such, the value of the HIV/HCV risk assessment itself as a means of increasing uptake of screening cannot be measured, although we observed that it did affect beliefs about the value of screening for participants themselves but not self-perception of risk. Beliefs in overall value screening might be a target for interventions which might affect screening uptake. The HIV/HCV risk self-assessment itself may have been an intervention that negated the necessity to address risk through an in-person intervention. This assessment reactivity effect possibility has been raised, mainly in substance abuse research.75 Future studies using a no-assessment control group or assessment of risk after the invitation for testing may be necessary to un-confound the potential interventional effect of a risk assessment and determine if a brief intervention, risk assessment, or both improves screening uptake more than a control condition. Further, because uptake of screening was relatively high, and because initial beliefs, opinions and self-perception of risk for these infections were the strongest predictors of screening uptake, selective utilization of HIV/HCV risk assessments and brief intervention could be a more efficient approach to screening. We hope to investigate this possibility in future studies.

Fourth, the level of drug misuse severity is minimally related to uptake of screening for these infections in this sample. This finding potentially indicates a disconnect between behaviors and risk, or that patients with the highest risk factors for HIV and HCV infections were not well represented in this sample. If the first explanation were true, it would imply that this disconnect would indicate the value of an intervention, although the brief intervention we applied in this study might not be the best approach to resolving this apparent problem. However, given the low IDU and other risk factors in this population, the indirect relationship between non-IDU and risk for HIV (primarily through sexual activity), and controversial association with HCV risk, it can be argued that the lack of an association between level of drug misuse severity and uptake of screening could be expected. On the other hand, it might indicate a need to revise the brief intervention to strengthen awareness of the link between drug use and misuse, risk for these infections, and need for screening.

The translation effect of the approaches employed in this study is not yet known. The methodologies and resultant findings from HIV screening studies in EDs have varied widely and makes direct comparisons challenging, although screening uptake in this study was relatively high. However, the application of the approach used in this study in other EDs might be limited to EDs that have the resources to use staff to conduct brief interventions and screening. Although this study demonstrated feasibility of performing a brief intervention among a drug using or misusing ED population to affect HIV/HCV screening uptake, it does not address how this approach might be implemented, and how it might be more or less efficacious than other approaches to improve HIV/HCV screening uptake in EDs. The use of existing staff or other models would be helpful in understanding if this approach can be implemented in a resource-responsive and effective manner. Future studies evaluating implementation strategies and direct comparisons to other approaches, so that an optimal approach or battery of approaches EDs might choose, are needed.

LIMITATIONS

Although care was taken to reach a representative sample of drug misusers at these two EDs, those who were excluded (e.g., presented when data were not collected, spoke languages other than English or Spanish, met exclusion criteria) might have different drug misuse profiles and responses to the risk assessment and brief intervention. The preponderance of marijuana-only users, who might have a lower risk profile for HIV/HCV, might have affected screening uptake and the effect of the brief intervention as well as the observed HIV and HCV prevalence. Subgroup analyses by substance use category were not possible under the limits of the sample of this study. In addition, this study cannot claim to represent the diversity of patients at all EDs, or those with dissimilar patient populations. The study eligibility assessment process during which patients were asked about their HIV/HCV status and testing history might also have affected enrollment, although few patients declined participation. Yet, it might have served to prime patients or pique their interest in testing, which might have increased HIV/HCV screening uptake, although this effect would likely be equal in both study arms. Unmeasured confounders could have influenced the study findings, despite the random assignment of participants and adjustments for covariates of interest. The brief intervention itself might not have been appropriate to the needs of these participants, even though it was theoretically grounded and its components were relevant to the topics discussed. Future studies can consider other approaches that might be more efficacious. The study also cannot measure what effect on the outcomes would have occurred if ED rather than research staff had administered the brief intervention. Other measures of drug misuse and HIV/HCV risk-taking behaviors might also have led to different study findings. Also, because no follow-up assessments were conducted with these participants, we cannot determine if the intervention had potentially positive effects on future HIV/HCV risk-taking behaviors, substance use, or HIV/HCV testing uptake. Further, although extensive training and preparation of the RAs was undertaken prior to the study onset, a defined brief intervention protocol used, and clinical oversight discussions conducted with the research assistants about their interventions, the brief intervention sessions were not audiotaped, and thus their precise content and fidelity were not monitored in this manner.

CONCLUSIONS

Uptake of combined rapid HIV and HCV screening is high and considered valuable among drug using/misusing ED patients with little concern about the ED as a venue for screening. Initial beliefs regarding the value of screening and self-perceived risk for these infections are the strongest predictor of uptake of screening. The brief intervention investigated in this study does not appear to change beliefs regarding screening, self-perceived risk, or uptake of screening for HIV and HCV in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research team gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Ms. Vera Bernardino for recruiting participants into the study and preparing the data for analysis and publication. The research team also would like to thank Ms. Ayanaris Reyes for helping initiate the project.

Disclosures: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA28645), the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Centers for AIDS Research (P30 AI042853), the Gilead Foundation and by an unrestricted donation of rapid hepatitis C test kits from OraSure Technologies, Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01419899. Dr. Merchant, an associate editor for this journal, had no role in the peer-review process or publication decision for this paper.

Footnotes

Presentations: none

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA, U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyer VA, U.S. Preventative Services Task Force Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:349–57. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw D, Matthews G, Danta M. Sexually transmitted hepatitis C infection: the new epidemic in MSM? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:66–72. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: 2013. (DAWN Series D-39). HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brillman JC, Crandall CS, Florence CS, Jacobs JL. Prevalence and risk factors associated with hepatitis C in ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:476–80. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.32642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelen GD, Green GB, Purcell RH, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in emergency department patients. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1399–404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205213262105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall MR, Ray D, Payne JA. Prevalence of Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus in a Grand Rapids, Michigan emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(3):401–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloan EP, McGill BA, Zalenski R, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus seroprevalence in an urban trauma population. J Trauma. 1995;38:736–41. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan AJ, Zone-Smith LK, Hannegan C, Norcross ED. The prevalence of hepatitis C in a regional level I trauma center population. J Trauma. 1992;33:126–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee KJ, Albertson TE, Kizer KW, Burns MJ, Hughes MJ, Ascher MS. A comparison of HIV-1, HBV, and HTLV-I/II seroprevalence rates of injured patients admitted through California emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:397–401. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galbraith JW, Franco RA, Rodgers JS, et al. Screening in emergency department identifies a large cohort of unrecognized chronic hepatitis C virus infection among baby boomers. Abstract LB-6. 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD 2013); Washington, DC. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed Apr 19, 2014];Viral hepatitis surveillance, United States 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/2011Surveillance/

- 17.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:271–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bender B, et al. Use of kiosks and patient understanding of opt-out and opt-in consent for routine rapid human immunodeficiency virus screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:287–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA. 2010;304:284–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman AE, Sattin RW, Miller KM, Dias JK, Wilde JA. Acceptance of rapid HIV screening in a southeastern emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1156–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sankoff J, Hopkins E, Sasson C, Al-Tayyib A, Bender B, Haukoos JS. Payer status, race/ethnicity, and acceptance of free routine opt-out rapid HIV screening among emergency department patients. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:877–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sattin RW, Wilde JA, Freeman AE, Miller KM, Dias JK. Rapid HIV testing in a southeastern emergency department serving a semiurban-semirural adolescent and adult population. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S60–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoxhaj S, Davila JA, Modi P, et al. Using nonrapid HIV technology for routine, opt-out HIV screening in a high-volume urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minniear TD, Gilmore B, Arnold SR, Flynn PM, Knapp KM, Gaur AH. Implementation of and barriers to routine HIV screening for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1076–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White DA, Scribner AN, Vahidnia F, et al. HIV screening in an urban emergency department: comparison of screening using an opt-in versus an opt-out approach. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haukoos JS, Witt MD, Coil CJ, Lewis RJ. The effect of financial incentives on adherence with outpatient human immunodeficiency virus testing referrals from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:617–21. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pisculli ML, Reichmann WM, Losina E, et al. Factors associated with refusal of rapid HIV testing in an emergency department. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:734–42. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walensky RP, Reichmann WM, Arbelaez C, et al. Counselor- versus provider-based HIV screening in the emergency department: results from the universal screening for HIV infection in the emergency room (USHER) randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White DA, Warren OU, Scribner AN, Frazee BW. Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in an emergency department despite an HIV screening program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:245–50. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ubhayakar ND, Lindsell CJ, Raab DL, et al. Risk, reasons for refusal, and impact of counseling on consent among ED patients declining HIV screening. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merchant RC, Clark MA, Langan TJt, Mayer KH, Seage GR, 3rd, DeGruttola VG. Can computer-based feedback improve emergency department patient uptake of rapid HIV screening? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S114–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aronson ID, Bania TC. Race and emotion in computer-based HIV prevention videos for emergency department patients. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:91–104. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calderon Y, Haughey M, Leider J, Bijur PE, Gennis P, Bauman LJ. Increasing willingness to be tested for human immunodeficiency virus in the emergency department during off-hour tours: a randomized trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:1025–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31814b96bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glick NR, Silva A, Zun L, Whitman S. HIV testing in a resource-poor urban emergency department. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:126–36. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.126.29391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrantz SJ, Babcock CA, Theodosis C, et al. A targeted, conventional assay, emergency department HIV testing program integrated with existing clinical procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Almeida KW, Kierzek G, de Truchis P, et al. Modest public health impact of nontargeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in 29 emergency departments. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:12–20. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christopoulos KA, Schackman BR, Lee G, Green RA, Morrison EA. Results from a New York City emergency department rapid HIV testing program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:420–2. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b7220f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta SD, Hall J, Lyss SB, Skolnik PR, Pealer LN, Kharasch S. Adult and pediatric emergency department sexually transmitted disease and HIV screening: programmatic overview and outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:250–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, Couture EF, Newman DR, Weinstein RA. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva A, Glick NR, Lyss SB, et al. Implementing an HIV and sexually transmitted disease screening program in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:564–72. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, et al. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):21–6. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czarnogorski M, Brown J, Lee V, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection in those who decline HIV screening in an urban emergency department. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011:879065. doi: 10.1155/2011/879065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merchant RC, Seage GR, Mayer KH, Clark MA, DeGruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christopoulos KA, Weiser SD, Koester KA, et al. Understanding patient acceptance and refusal of HIV testing in the emergency department. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pringle K, Merchant RC, Clark MA. Is self-perceived HIV risk congruent with reported HIV risk among traditionally lower HIV risk and prevalence adult emergency department patients? Implications for HIV testing. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:573–84. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cherpitel CJ, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Ye Y, Bond J. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in a Polish emergency department: three-month outcomes of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:982–90. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonar EE, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Computer-enhanced interventions for drug use and HIV risk in the emergency room: preliminary results on psychological precursors of behavior change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carey MP, Coury-Doniger P, Senn TE, Vanable PA, Urban MA. Improving HIV rapid testing rates among STD clinic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2008;27:833–8. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn KE, Saulsgiver KA, Patrick ME, Heil SH, Higgins ST, Sigmon SC. Characterizing and improving HIV and hepatitis knowledge among primary prescription opioid abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:625–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. A randomized controlled trial utilizing motivational interviewing to reduce HIV risk and drug use in young gay and bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:9–18. doi: 10.1037/a0035311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:328–35. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2007. (NSDUH Series H-32). Office of Applied Studies. DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Humeniuk R, Ali R. [Accessed Apr 19, 2014];Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and pilot brief intervention: a technical report of phase II findings of the WHO ASSIST Project. Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/assist_technicalreport_phase2_final.pdf.

- 56.Youmans Q, Merchant RC, Baird JR, Langan TJt, Nirenberg T. Prevalence of alcohol, tobacco and drug misuse among Rhode Island hospital emergency department patients. Med Health R I. 2010;93:44–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jobe JB, Mingay DJ. Cognitive research improves questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1053–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sudman S, Bradburn NM, Schwarz N. Thinking about answers: the application of cognitive processes to survey methodology. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willis GB, Royston P, Bercini D. The use of verbal report methods in the development and testing of survey questionnaires. Appl Cog Psychol. 1991;5:251–67. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. SAGE Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merchant RC, Freelove SM, Langan TJ, et al. The relationship of reported HIV risk and history of HIV testing among emergency department patients. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:61–74. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trillo AD, Merchant RC, Baird JR, Ladd GT, Liu T, Nirenberg TD. Interrelationship of alcohol misuse, HIV sexual risk and HIV screening uptake among emergency department patients. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Merchant RC, Clark MA, Seage GR, 3rd, Mayer KH, Degruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient perceptions and preferences on opt-in rapid HIV screening program components. AIDS Care. 2009;21:490–500. doi: 10.1080/09540120802270284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones PS, Lee JW, Phillips LR, Zhang XE, Jaceldo KB. An adaptation for Brislin's translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs Res. 2001;50:300–4. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry WJ, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1986. pp. 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carroll JS, Holman TB, Segura-Bartholomew G, Bird MH, Busby DM. Translation and validation of the Spanish version of the RELATE questionnaire using a modified serial approach for cross-cultural translation. Fam Process. 2001;40:211–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fernandez Huerta JM. [Simple readability measures] (Spanish) Consigna. 1959;214:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller WRRS. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kinzie MB. Instructional design strategies for health behavior change. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64:527–37. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Edlin BR. Hepatitis C screening: getting it right. Hepatology. 2013;57:1644–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.26194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277:301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.