Abstract

Rb is critical for promoting cell cycle exit in cells undergoing terminal differentiation. Here we show that during erythroid terminal differentiation, Rb plays a previously unappreciated and unorthodox role in promoting DNA replication and cell cycle progression. Specifically, inactivation of Rb in erythroid cells led to stressed DNA replication, increased DNA damage, and impaired cell cycle progression, culminating in defective terminal differentiation and anemia. Importantly, all of these defects associated with Rb loss were exacerbated by the concomitant inactivation of E2f8. Gene expression profiling and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) revealed that Rb and E2F8 cosuppressed a large array of E2F target genes that are critical for DNA replication and cell cycle progression. Remarkably, inactivation of E2f2 rescued the erythropoietic defects resulting from Rb and E2f8 deficiencies. Interestingly, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) on E2F2 ChIPs indicated that inactivation of Rb and E2f8 synergizes to increase E2F2 binding to its target gene promoters. Taken together, we propose that Rb and E2F8 collaborate to promote DNA replication and erythroid terminal differentiation by preventing E2F2-mediated aberrant transcriptional activation through the ability of Rb to bind and sequester E2F2 and the ability of E2F8 to compete with E2F2 for E2f-binding sites on target gene promoters.

INTRODUCTION

Erythroid cells represent a well-established model system to study terminal differentiation. Erythroid terminal differentiation in mammals is a tightly controlled multistep process that is intimately coupled to the cell cycle (1, 2). It begins at the earliest morphologically recognizable erythroid cells, the proerythroblasts (ProE). ProE undergo 3 to 4 rapid, successive mitotic cell divisions and incur profound maturational changes to generate series of morphologically distinct erythroblasts (EB): basophilic erythroblasts (BasoE), polychromatic erythroblasts (PolyE), and orthochromatic erythroblasts (OrthoE). OrthoE then permanently exit the cell cycle and enucleate to become reticulocytes (Retic), which undergo further maturational changes to become erythrocytes, or mature red blood cells (RBC). Given the intimate link of the cell cycle to erythroid terminal differentiation, it is not surprising that perturbation of the delicate balance between active proliferation and permanent cell cycle exit often results in defective erythroid terminal differentiation and anemia (1–3).

As a transcriptional corepressor, retinoblastoma (Rb) controls a key cell cycle checkpoint at the G1/S transition (4, 5). Consistent with an important role of cell cycle control in erythroid terminal differentiation and erythropoiesis, Rb knockout (KO) embryos are anemic (6–8), a defect that can be suppressed by a functionally normal placenta (9, 10). In addition, inactivation of Rb specifically in hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) or the erythroid lineage leads to mild anemia and mild splenomegaly (11–14). Interestingly, while the role of Rb in the control of postnatal erythropoiesis is cell autonomous (12, 13), Rb appears to elicit both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous signals to maintain normal erythropoiesis during embryogenesis (10, 15, 16). These data suggest that Rb may make different contributions to embryonic erythropoiesis and postnatal erythropoiesis.

It is largely accepted that Rb exerts its function mainly through its interactions with the E2F family of transcription factors (4, 5, 17–20). In mammalian cells, there are eight E2f genes (E2f1 to E2f8) that encode nine E2F proteins, with the E2f3 locus encoding two isoforms, E2F3a and E2F3b (4, 5, 17–20). Based on their structural domains and their impact on gene transcription, E2Fs can be broadly divided into two groups (18). The activator group, consisting of E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3, transcriptionally activates E2F target genes during the G1/S transition of the cell cycle when they are released from Rb binding and inhibition. On the other hand, members of the repressor group transcriptionally repress E2F target genes in quiescent or terminally differentiated cells. Based on their structural domains, the repressor group can be further divided into two subclasses, canonical repressors (E2F4, E2F5, and E2F6) and atypical repressors (E2F7 and E2F8). While transcriptional repression mediated by E2F4 and E2F5 depends on their binding to the Rb pocket protein and the other two pocket proteins, p107 and p130, E2F6-, E2F7-, and E2F8-mediated repression is thought to be pocket protein independent, as none of them contain the consensus pocket-protein-binding domain. Although E2F6 has been shown to exert its repressor function through a polycomb repressor complex (21), it is unclear how E2F7 and E2F8 impose transcriptional repression. Consistent with the intimate interactions between Rb and Rb-pocket-protein-binding E2Fs (i.e., E2F1 to E2F5), numerous studies using in vivo mouse models have shown that E2Fs, particularly activator E2Fs, are important mediators for Rb function in the nervous system, lenses, placentae, and fetal livers (FL) (16, 22–29). However, whether non-pocket-protein-binding E2Fs, namely, E2F6, E2F7, and E2F8, can also mediate Rb function is largely unknown.

We recently uncovered a surprising functional interaction between Rb and E2F8 in the erythroid lineage (12). Specifically, while the inactivation of Rb or E2f8 in HSC or the erythroid lineage led to mild erythropoietic defects, the concomitant inactivation of both genes synergized to trigger severe anemia, which is characterized by profound ineffective erythropoiesis and mild hemolysis. Here we report that the concomitant ablation of Rb and E2f8 in HSC or the erythroid lineage led to a partial differentiation block at a critical stage of erythroid terminal differentiation where cells are programmed to permanently exit the cell cycle. Importantly, we also show that the loss of Rb triggered a series of cell cycle defects that have been previously unappreciated, including stressed DNA replication and prolonged cell cycle progression. Interestingly, these defects were exacerbated by the concomitant loss of E2f8 but were rescued by the inactivation of E2f2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mouse lines used in this study were described previously (30–33). Mx1-Cre-mediated deletion was achieved by 3 to 5 intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 400 μg of poly(I·C) (Sigma) every other day in 4-week-old mice. Mice were sacrificed 8 to 12 weeks after the poly(I·C) injection. EpoR-GFPCre-mediated knockout (KO) mice were sacrificed at 2 to 3 months of age. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

Complete blood counts.

Complete blood count (CBC) analysis was done on an automated instrument (Hemavet FS950; Drew Scientific). Hematological findings were confirmed with peripheral blood smears.

Erythroid cell staging and sorting.

Erythroid cells were staged as previously described (34), using CD44 and forward scatter (FSC)-based fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with CD16/32 blockers (BD Biosciences) and BD Biosciences antibodies against Ter119 (catalog number 553673), CD44 (catalog number 559250), CD11b (catalog number 557657), CD45 (catalog number 557689), and Gr-1 (catalog number 557661). 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; BD Biosciences) was used to exclude dead cells. Single-stage erythroid cells were profiled/sorted on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with Diva software (BD Biosciences). The Ter119+ CD71high population was sorted with eBiosciences antibodies against Ter119 (catalog number 12-5921-83) and CD71 (catalog number 11-0711-85) on a FACSVantage cell sorter (BD Biosciences). For improved cell viability, special sheath buffer (PB2) was used as previously described (35).

ImageStream multispectral imaging analysis.

ImageStream multispectral imaging analysis was done as previously described (36). Briefly, single-cell suspensions of bone marrow (BM) and spleen were blocked with 12.5% rat serum (Sigma) and then stained with Ter119-biotin (catalog number 553672; BD Biosciences) and c-Kit–phycoerythrin (PE) (catalog number 105807; BioLegend) antibodies at 1:100 dilutions and thiazol orange (Sigma) at 2 μg/ml. After a brief wash step, secondary antibody staining was done with PE-Texas Red-streptavidin (catalog number 551487; BD Biosciences) at a 1:400 dilution. After the final wash step, cells were stained with 20 μM Draq5 (Cell Signaling) and analyzed on an ImageStream 100 flow cytometer (EMD Millipore).

Intracellular staining.

For the in vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay, BrdU (Sigma) was administered through i.p. injection at a concentration of 150 μg/g of body weight. Mice were sacrificed after 45 min. Single-cell suspensions prepared from BM cells were stained for erythroid staging as described above, followed by intracellular marker staining with BrdU antibodies using a BrdU-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For γH2AX and phospho-histone 3 (PH3) staining, after staining for erythroid staging, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antibodies against γH2AX (catalog number 16-202A; EMD Millipore) or PH3 (catalog number 06-570; EMD Millipore). For all intracellular marker staining, cells were also stained with 7-AAD to assess the DNA content and were analyzed with Diva software on the FACSAria II cell sorter.

In vitro erythroid differentiation.

An in vitro erythroid differentiation assay was performed as previously described (37).

Gene expression analysis.

RNA was isolated with RNeasy Plus (Qiagen) by using the sorted Ter119+ CD71high population from spleens. Microarray analysis was done on a Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), RNA was isolated from the sorted Ter119+ CD71high population or sorted single-stage erythroid cells. cDNA was synthesized with a first-strand synthesis kit from Invitrogen (catalog number 12328-040). A Sybr green gene expression kit (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the expression levels of genes of interest. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 1% NP-40). Five hundred micrograms of protein lysates was incubated with 2 μg of E2F1 (catalog number sc-193), E2F2 (catalog number sc-633), E2F3 (catalog number sc-878), and E2F8 (catalog number sc-161540) antibodies from Santa Cruz or IgG for 3 h and then with protein G magnetic beads from Millipore (catalog number LSKMAGG02) for another 3 h. Beads were washed with immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer five times and incubated with sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C. Proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and blocked in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h. The blocked membrane was then incubated with the primary E2F antibodies listed above and Rb antibodies (catalog number sc-50; Santa Cruz) at a 1:1,000 dilution in 5% milk–TBST for 2 h. Membranes were subsequently incubated with either conventional or light-chain-specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (catalog number 205-032-176; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) (1:2,000) for 2 h in 5% milk–TBST. Proteins were visualized by using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed by using Magna ChIP protein G-coupled magnet beads (Upstate, Millipore), according to the manufacturer's recommendations, on Ter119+ CD71high BM cells with 5 to 10 μg antibodies (E2F2 [catalog number sc-633] and E2F8 [catalog number sc-161540]; Santa Cruz). The corresponding IgGs served as negative controls. Primers used to amplify the eluted DNA by either conventional PCR or qPCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Molecular combing.

Freshly harvested fetal liver (FL) cells from embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) embryos were labeled with 25 μM iododeoxyuridine (IdU) (catalog number I-7125; Sigma) for 20 min, followed by 20 min of labeling with 50 μM 5-chloro-2′-deoxyuridine (CldU) (catalog number 105478; MP Biomedicals). Labeled OrthoE were sorted by using CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging as described above. Genomic DNA was isolated, digested, combed, and immunostained as described previously (38). Images were taken with a Pathway 855 Bioimager (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed by using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis.

Unless specified otherwise, all statistical analyses were done by using Student's t test with a significance threshold of a P value of <0.05.

Microarray data accession number.

Raw data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE52157 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=alsbaagohhctdqp&acc=GSE52157).

RESULTS

Rb and E2F8 cosuppress E2F-responsive genes important for DNA replication and cell cycle progression.

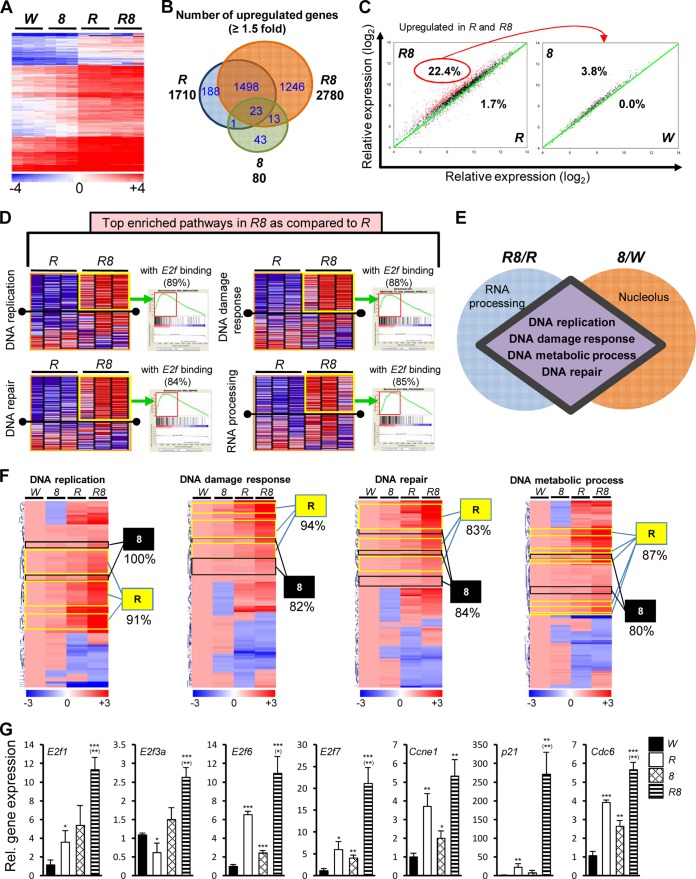

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the synergy of Rb loss and E2F8 loss, we used gene expression profiling to assess molecular changes in Mx1-Cre-mediated KO mice using RNA isolated from sorted Ter119+ CD71high EB. Consistent with the known repressor role of E2F8 and the corepressor role of Rb, the loss of Rb and/or E2f8 led to the upregulation of a plethora of genes (Fig. 1A). Specifically, gene expression profiles for the control mice and the E2f8 KO mice were similar, with very few (80) genes being upregulated in the E2f8 KO mice (Fig. 1A and B). These data are consistent with our previous finding that inactivation of E2f8 alone had virtually no effect on erythropoiesis (12). In addition, gene expression profiles for the Rb KO mice and the Rb;E2f8 double-KO (DKO) mice were also similar, although there were greater gene expression changes in the DKO mice than in the Rb KO mice (Fig. 1A). Importantly, a significant number of genes (1,246, or 44.8%) were specifically upregulated in the DKO mice (Fig. 1B), indicating that the loss of Rb and E2F8 synergizes to activate gene transcription. Interestingly, while 665 genes (22.4%) that were upregulated in the Rb KO mice and the DKO mice were additively or synergistically upregulated in the DKO mice, only 25 (3.8%) of these 665 genes were upregulated in the E2f8 KO mice compared to the control mice (Fig. 1C), suggesting that although the loss of E2F8 alone did not elicit significant gene expression changes, it triggered major derepression of target genes in the absence of Rb. In addition, intravascular hemolysis observed in the DKO mice and the compensational increases in cellular proliferation of erythroid precursors (12) may also contribute to the upregulation of many genes in DKO mice.

FIG 1.

Mx1-Cre-mediated inactivation of Rb and E2f8 synergizes to upregulate E2F-responsive genes. (A) Heat map showing hierarchical clustering of genes that were upregulated in Rb; E2f8 DKO mice compared to control mice (n = 3). In all figures, “W” indicates RbloxP/loxP or Mx1+/Cre mice, “R” indicates RbΔ/Δ mice, “8” indicates E2f8Δ/Δ mice, and “R8” indicates RbΔ/Δ E2f8Δ/Δ mice. A cutoff of 1.5-fold expression compared to W was used. (B) Venn diagrams showing the number of upregulated genes in different KO groups compared to W using a cutoff of 1.5-fold. (C, left) Scatter plot of upregulated genes in R and R8 from panel B showing upregulated (red dots) or downregulated (blue dots) genes in R8 compared to R. (Right) Scatter plot of upregulated genes from the left panel showing upregulated (red dots) or downregulated (blue dots) genes in 8 compared to W. A cutoff of 1.5-fold was used for both plots, with black dots showing genes with expression changes within the cutoff. (D) GSEA heat maps and enrichment plots of enriched pathways upregulated in R8 compared to R. Enriched genes are outlined by yellow boxes in the heat maps and by red boxes in the enrichment plots. (E) Diagram showing shared and unique upregulated pathways in R8 compared to R and in 8 compared to W based on GSEA. Only the top five upregulated pathways were chosen for each comparison. (F) Heat maps of shared pathways from panel E highlighting the R clusters (yellow boxes) and the 8 clusters (black boxes). Numbers under each cluster represent the percentages of genes with E2f-binding sites identified by TFSEARCH. (G) qRT-PCR of Ter119+ CD71high EB from mice of the indicated genotypes for representative genes that showed synergic or additive upregulation in DKO mice based on data shown in panel A (n = 3). Unless specified otherwise, in all figures, asterisks indicate statistical comparisons to W mice, and asterisks in parentheses indicate statistical comparisons to RbΔ/Δ mice (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Given the similar gene expression signatures of Rb KO mice and DKO mice and the overall moderate upregulation of genes in DKO mice compared to Rb KO mice, we used gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (39) to compare gene expression patterns of the two genotypic groups of mice for 1,453 gene sets/pathways. GSEA allows the identification of highly enriched gene sets even with subtle expression changes for individual genes. We obtained a list of pathways that showed statistically significant enrichment (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The top four upregulated and enriched pathways in DKO mice included DNA replication, the DNA damage response, DNA repair, and RNA processing (Fig. 1D; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). To understand whether the E2f8 KO mice harbored similar molecular changes as those harbored by the DKO mice, we identified pathways that were upregulated in E2f8 KO mice compared to control mice. Surprisingly, despite the absence of anemia, E2f8 KO mice displayed molecular changes strikingly similar to those displayed by DKO mice, sharing four of the top five enriched pathways (Fig. 1E; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Upon further examinations of genes with synergistic or additive upregulation in DKO mice, we identified two distinct clusters: cluster R, where most of the genes had higher levels of expression in Rb KO than in E2f8 KO mice, and cluster 8, where most of the genes had higher levels of expression in E2f8 KO than in Rb KO mice (Fig. 1F; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). However, the relative contributions of Rb and E2F8 to these pathways do not seem to be equal, as there were more genes represented in cluster R than in cluster 8 (Fig. 1F; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, while the majority (i.e., >80%) of upregulated genes in the enriched sections of the shared pathways (Fig. 1F) or the top four pathways in DKO mice (Fig. 1D) contained an E2f-binding site(s) in their promoters, the percentages of E2F-binding-site-containing genes in the top four pathways (Fig. 1D) without gene expression changes are much lower: 62% for DNA replication, 53% for the DNA damage response, 55% for DNA repair, and 65% for RNA processing. These data suggest that Rb and E2F8 largely repress these genes through the E2f-binding sites. Importantly, qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes that are synergistically or additively upregulated in DKO mice confirmed the microarray data (Fig. 1G). Collectively, our data suggest that Rb and E2F8 coregulate E2F-responsive genes that are involved in DNA replication, the DNA damage response, DNA metabolic processes, and DNA repair, processes that are important for cell cycle progression.

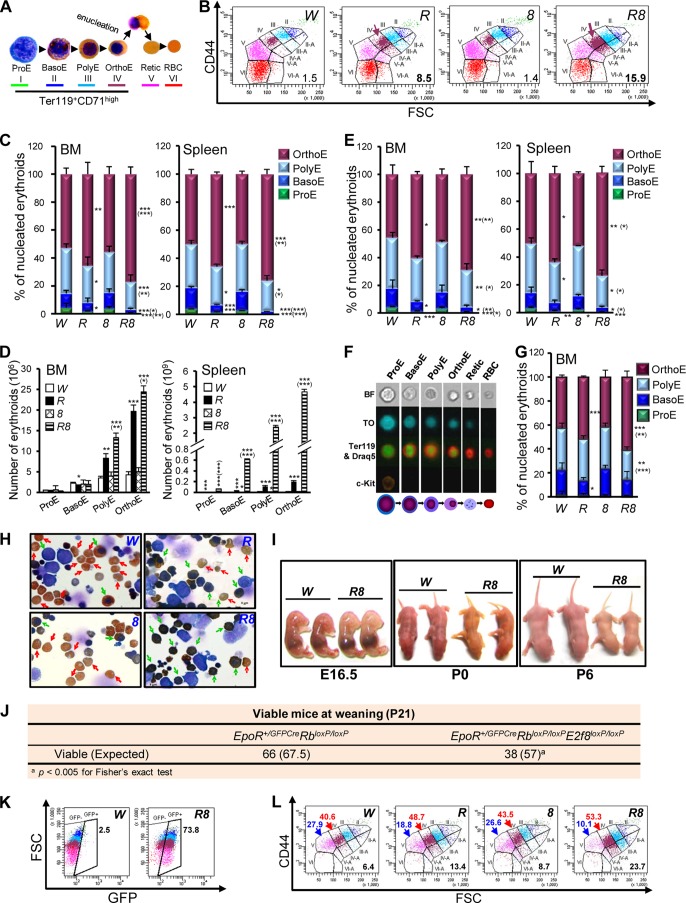

Rb KO and Rb; E2f8 DKO erythroid cells are enriched at the OrthoE stage and are macrocytic.

The gene expression data presented above underscore the collaborative role of Rb and E2F8 in the control of DNA replication and cell cycle progression in erythroid cells. Given the intimate link between cell cycle control and erythroid terminal differentiation, we sought to determine whether the ineffective erythropoiesis observed in the DKO mice can be explained by impaired cell cycle progression. To this end, we first determined whether the ineffective erythropoiesis seen in the DKO mice is associated with a defined stage of erythroid differentiation by using a much improved, CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging system (34), which allowed us to sort erythroid cells or Ter119+ cells into six much-better-separated subpopulations (subpopulations I to VI) (see Fig. S1A to G in the supplemental material) than the CD71-FSC-based staging system (40). Importantly, microscopic examination of cytospins prepared from the sorted subpopulations from bone marrow (BM) cells of wild-type mice confirmed that the six subpopulations represent each of the six morphologically distinguishable differentiation stages (Fig. 2A), with much higher purities (i.e., 91.1 to 99.2%) (see Fig. S1H and I in the supplemental material) than those with the CD71-FSC-based staging system (40). Using this staging system, we found that in both the BM and the spleen of Rb KO mice, there was significant enrichment of OrthoE (and PolyE, to a lesser extent) and depletion of Retic and RBC, defects that were more profound in the DKO mice (Fig. 2B and C). Although the percentages of ProE and BasoE were significantly reduced in Rb KO and DKO mice compared to control mice (Fig. 2C), the absolute numbers of immature cells in these two KO groups were either similar to or more than those in control mice due to stress erythropoiesis in response to anemia (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, CD44-FSC profiles also revealed that both nucleated and enucleated erythroid cells from the DKO mice (and, to a lesser extent, the Rb KO mice) had a wider size range and were larger than those from the control mice (Fig. 2B), reminiscent of clinical findings for human patients with macrocytic anemia, including megaloblastic anemia. Consistent with the erythroid-intrinsic synergy of Rb and E2F8 in promoting erythropoiesis (12), the role of Rb and E2F8 in ensuring normal erythroid terminal differentiation is erythroid intrinsic, as EpoR-GFPCre-mediated inactivation of Rb and E2f8 specifically in the erythroid lineage recapitulated the phenotypes described above (Fig. 2B and E). The above-mentioned differentiation defects were also independently confirmed by ImageStream flow cytometric analysis (36), which combines flow cytometry and single-cell imaging to separate erythroid cells into six differentiation stages (Fig. 2F and G).

FIG 2.

Erythroid cells deficient for Rb and E2f8 are enriched at the OrthoE stage and are macrocytic. (A) Representative microscopic images of benzidine- and Giemsa-stained mouse BM cells representing the six stages of erythroid terminal differentiation. Stages I to IV represent the Ter119+ CD71high subpopulation of erythroid cells. (B) Representative CD44-FSC-based flow cytometric profiles of BM erythroid cells from mice of the indicated genotypes. Subpopulations II to VI represent the corresponding stages depicted in panel A, and subpopulations II-A to VI-A represent “larger” erythroid cells of their corresponding differentiation stages II to VI. Numbers represent percentages of all “larger” erythroid cells (subpopulations II-A to VI-A). (C) CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging for nucleated erythroid cells from mice of the indicated genotypes (n ≥ 3). (D) Absolute numbers of different stages of EB from mice of the indicated genotypes calculated based on data in panel B and total numbers of BM cells and spleen cells from each mouse (n = 3). (E) CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging for nucleated EB from mice of the indicated genotypes (n ≥ 3). (F) Representative ImageStream images for the six differentiation stages of EB (top) and a cartoon depicting the six corresponding stages (bottom). (G) Percentages of nucleated EB from erythroid staging determined by ImageStream analysis (n ≥ 3). (H) Representative images of benzidine- and Wright-Giemsa-stained cytospins prepared from lineage-depleted BM cells harvested 2 days after differentiation induction in an in vitro erythroid differentiation assay. Red arrows depict representative enucleated erythroid cells (i.e., Retic and RBC), and green arrows depict representative nucleated erythroid cells. (I) Representative images of E16.5 embryos and pups from postnatal day 0 (P0) and P6. (J) Analysis of viable pups at postnatal day 21 (P21) that were derived from intercrosses between RbloxP/loxP and EpoR+/GFPCre; RbloxP/loxP mice or between RbloxP/loxP; E2f8loxP/loxP and EpoR+/GFPCre; RbloxP/loxP; E2f8loxP/loxP mice. (K) Representative flow cytometric plots showing GFP expression in FL erythroid cells. Numbers represent the percentages of GFP+ erythroid cells. (L) Representative CD44-FSC-based flow cytometric profiles of all FL erythroid cells. Numbers represent percentages of OrthoE (red), Retic (blue), and macrocytic cells (subpopulations II-A to VI-A) (black). Data in panels A to D and F to H are from the Mx1-Cre system, and data in panels E and I to L are from the EpoR-GFPCre system.

To complement the in vivo erythroid staging analyses described above, we isolated lineage-depleted HSC and progenitors from the BM, expanded them in the presence of erythropoietin (EPO; Amgen) to favor the erythroid lineage, and differentiated them in vitro into Retic and RBC. As shown in Fig. 2H, at day 2, when the majority of control and E2f8 KO cells differentiated and efficiently enucleated, DKO cells and Rb KO cells (to a lesser extent) were impaired in undergoing terminal differentiation and enucleation, as evidenced by many nucleated erythroid progenitors, fewer enucleated cells, and weaker benzidine staining, resembling the differentiation defects observed in vivo (Fig. 2B and C). Taken together, data from our in vivo erythroid staging and in vitro erythroid differentiation assays indicate that DKO erythroid cells experienced significant enrichment of OrthoE and reduction of Retic and RBC, leading to the severe anemia.

Rb and E2F8 collaborate to promote embryonic erythropoiesis.

We have previously shown that the concomitant ablation of Rb and E2f8 specifically in the erythroid lineage by the EpoR-GFPCre knock-in allele (30) synergized to induce severe anemia in adult mice (12). Analysis of prenatal and postnatal EpoR+/GFPCre; RbloxP/loxP; E2f8loxP/loxP mice revealed that anemia was already evident in E16.5 embryos (Fig. 2I). Compared to the pinkish newborn control mice, newborn DKO mice had a distinct yellowish coloration (postnatal day zero [“P0”]) (Fig. 2I), exhibited growth retardation (“P0”) (Fig. 2I), failed to thrive (“P6”) (Fig. 2I), and showed reduced viability at weaning (Fig. 2J). Given the anemic appearance of the DKO embryos, we determined whether FL-derived erythropoiesis was also compromised. Since the EpoR-GFPCre allele also expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) (30), we used flow cytometric analysis to assess Cre expression using GFP as a surrogate. As shown in Fig. 2K, in FL cells from E15.5 DKO embryos, 73.8% of erythroid cells were GFP positive (GFP+), suggesting that Cre is expressed in the majority of erythroid cells in the FL. Importantly, CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging of FL cells from E15.5 control and KO embryos showed enrichment of OrthoE and a reduction of Retic in DKO embryos (and, to a lesser extent, Rb KO embryos) compared to control embryos or E2f8 KO embryos (Fig. 2L). Like their BM counterparts, Rb KO and DKO FL erythroid cells were also macrocytic (Fig. 2L). These data suggest that Rb and E2F8 collaborate to promote erythroid terminal differentiation for both FL-derived embryonic erythropoiesis and BM-derived postnatal erythropoiesis.

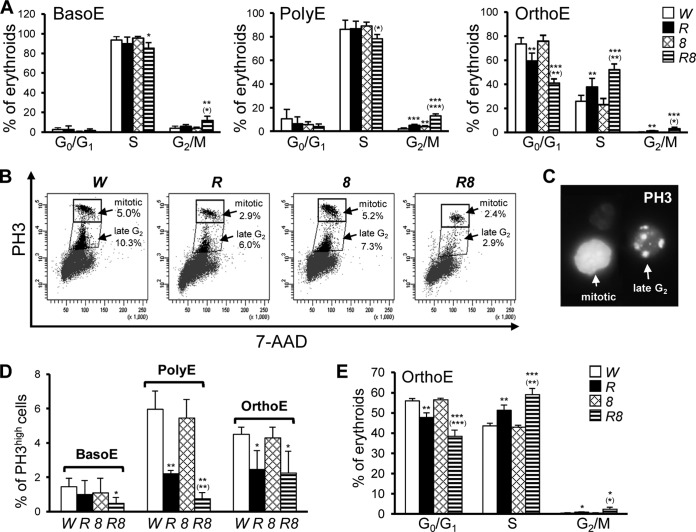

Rb KO and Rb; E2f8 DKO erythroid cells display distinct cell cycle defects.

Since one key event during erythroid terminal differentiation is timely cell cycle exit at the OrthoE stage, we sought to determine whether cell cycle dysregulation contributes to the enrichment of OrthoE in Rb KO mice and DKO mice. Using an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging for BM cells, we observed that in control mice, the vast majority of BasoE and PolyE were in S phase (Fig. 3A), consistent with their expected highly proliferative status. However, there was no significant increase in proportions of S-phase cells for these two early stages of EB from any group of KO mice compared to those from the control mice. In sharp contrast, there was a significant increase in the number of OrthoE in S phase in Rb KO mice compared to control mice, a phenotype that was more severe in the DKO mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, in the DKO mice, there were significant increases in numbers of G2/M-phase cells for all three differentiation stages (Fig. 3A). To determine whether the G2/M-phase cells in the Rb KO mice and the DKO mice were mitotic or still in the G2 phase, we used a widely accepted mitotic marker, phospho-histone 3 (PH3), to quantify mitotic cells or late-G2-phase cells. Surprisingly, despite increased percentages of S-phase cells and G2/M-phase cells, DKO EB, and, to a lesser extent, Rb KO EB, showed a decreased number of cells in mitosis or in late G2 phase (Fig. 3B to D), strongly suggesting a slow G2/M transition or the presence of an early G2 arrest in these EB. These data are consistent with a previous report showing that in addition to regulating the G1/S transition, the Rb/E2F pathway also plays an important role during the G2/M transition (41). Importantly, all of the above-mentioned cell cycle defects were also observed in OrthoE from Rb KO FL cells and DKO FL cells (Fig. 3E).

FIG 3.

EpoR-GFPCre-mediated inactivation of Rb and E2f8 in erythroid cells leads to cell cycle defects during erythroid terminal differentiation. (A) Cell cycle analysis of EB from BM based on an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging (n ≥ 3). (B) Representative flow cytometric plots of PH3high and PH3low populations in combined BasoE, PolyE, and OrthoE stages. (C) Representative microscopic image of sorted cells in panel B showing PH3high (mitotic) and PH3low (late-G2-phase) cells. (D) Quantification of PH3high cells in BasoE, PolyE, and OrthoE from data in panel B (n = 3). (E) Cell cycle analysis of FL OrthoE based on an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging (n ≥ 3).

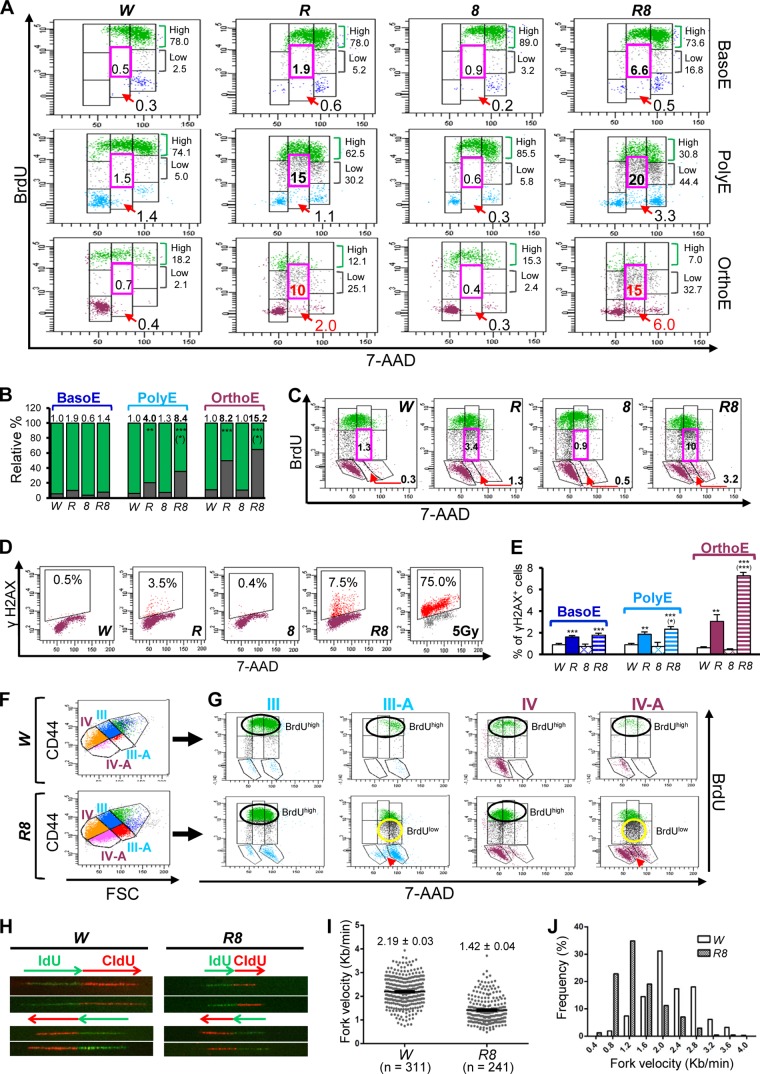

Rb KO and DKO OrthoE experience stressed DNA replication.

Previous studies have shown that inactivation of Rb in cells undergoing terminal differentiation in lenses, hind brains, placentae, and muscles led to an increase in the number of BrdU+ cells, assessed by BrdU immunostaining (16, 27, 29, 42). These data were interpreted as unscheduled DNA replication resulting from the loss of G1/S checkpoint control by Rb. However, the increased number of BrdU+ cells may also be a result of slower S-phase progression. To explore this possibility, we assessed levels of BrdU uptake by examining flow cytometric profiles from the in vivo BrdU incorporation assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, in the control mice and the E2f8 KO mice, the vast majority of BrdU+ cells had high levels of BrdU uptake (green dots), indicating efficient DNA replication. In sharp contrast, in Rb KO mice, EB, particularly late stages of EB (i.e., PolyE and OrthoE), had markedly lower BrdU uptake than did those from either control or E2f8 KO mice. For example, in the Rb KO mice, despite the presence of increased numbers of OrthoE in S phase, there was a 14-fold increase in the BrdUlow subpopulation with S-phase DNA content (Fig. 4A, pink boxes) compared to the control mice (i.e., 0.7% versus 10%) (Fig. 4A), strongly suggesting the presence of stressed DNA replication. In Rb KO OrthoE, even cells with DNA content close to 4n often had lower rates of BrdU uptake, further supporting the presence of stressed DNA replication. Importantly, this defect progressively worsened during terminal differentiation, as in the Rb KO mice, there was a gradual increase in the ratio of BrdUlow cells to BrdUhigh cells from BasoE to OrthoE compared to the control mice (Fig. 4A and B). As expected, all the defects described above were exacerbated in DKO mice (Fig. 4A and B) and were recapitulated in FL cells (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that Rb and E2F8 collaborate to prevent stressed DNA replication.

FIG 4.

Inactivation of Rb and E2f8 by EpoR-GFPCre synergizes to trigger stressed DNA replication. (A) Representative cell cycle profiles for sorted BM cells from an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging (n = 3). Cells were gated for G0/G1 phase, S-phase BrdUlow (gray dots) and S-phase BrdUhigh (green dots) cells, BrdUlow cells with S-phase DNA content (2n to 4n) (pink boxes), BrdU− cells with S-phase DNA content (red arrows), and cells in G2/M phase. (B) Percentage of BrdUhigh (green) and BrdUlow (gray) cells from data in panel A (n = 3). Numbers above each bar represent average fold changes of the ratios of BrdUlow/BrdUhigh cells in the KO groups compared to those in W. (C) Representative cell cycle profiles for OrthoE in FL cells from E15.5 embryos assessed by an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging. Numbers in pink boxes represent percentages of BrdUlow cells with S-phase DNA content, and numbers by red arrows represent percentages of BrdU− cells with S-phase DNA content. (D) Representative flow cytometric plots of γH2AX+ OrthoE from BM cells. Wild-type BM cells irradiated with 5 Gy of gamma rays served as a positive control. (E) Quantifications of γH2AX+ BM cells from mice of the indicated genotypes (n = 3). (F and G) Representative CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging profiles (F) and representative cell cycle profiles (G) of PolyE and OrthoE from FL cells of E15.5 W and R8 embryos to compare normocytic EB with macrocytic EB, highlighting cells with high BrdU uptake (BrdUhigh) (black circles), low BrdU uptake (BrdUlow) (yellow circles), or no BrdU uptake (BrdU−) (red arrowheads). (H) Representative images from molecular combing analysis. (I) Beeswarm plots of DNA replication fork velocity of OrthoE in FL cells from E13.5 embryos. Single replication signals are presented as individual dots, with mean values ± standard errors of the means being depicted as black lines/bars. Numbers are mean values ± standard errors of the means. n indicates the number of DNA fibers scored. (J) Histogram of fork velocity distribution of data from panel F (P < 0.0001 by Mann-Whitney test).

Consistent with the presence of DNA replication stress in Rb KO mice and DKO mice, OrthoE (and, to a lesser extent, BasoE and PolyE) from both mutant mice also showed increased DNA damage, as evidenced by a 7-fold increase (for Rb KO mice) and a 15-fold increase (for DKO mice) in the numbers of cells positive for γH2AX (Fig. 4D and E), a classical marker for double-stranded DNA breaks. In addition, OrthoE from both mutant mice accumulated significantly higher numbers of BrdU-negative (BrdU−) cells with S-phase DNA content (Fig. 4A and C, red arrows). These data suggest an extended S phase or the presence of S-phase arrest in Rb KO OrthoE and DKO OrthoE, a defect that is reminiscent of the increased subpopulations of EB with S-phase DNA content but lacking active DNA synthesis that were observed previously in human patients with megaloblastic anemia (43, 44). Furthermore, although in control embryos, both macrocytic and normocytic EB with 2n to 4n DNA content had similarly high levels of BrdU uptake (Fig. 4G, black circles), in the DKO embryos, a substantial fraction of macrocytic EB with 2n to 4n DNA content had either low BrdU uptake (Fig. 4G, yellow circles) or no BrdU uptake (Fig. 4G, red arrowheads), despite the fact that the majority of their normocytic counterparts had high levels of BrdU uptake (Fig. 4F and G). Together, our data strongly suggest that Rb KO OrthoE and DKO OrthoE, instead of exiting the cell cycle, experienced progressively worsening defects in DNA replication, DNA damage, and cell cycle progression, leading to impaired cell cycle progression, macrocytosis, and a partial differentiation block.

To delineate the cellular mechanisms underlying the DNA replication stress described above, we employed a DNA molecular combing approach to directly assess the DNA replication speed of sorted OrthoE from FL cells of E13.5 embryos. As shown in Fig. 4H and I, OrthoE from a DKO embryo showed a 35% reduction of replication fork velocity compared to those from the control embryo (1.42 ± 0.04 kb/min versus 2.19 ± 0.03 kb/min; P = 2E−46 by Student's t test). Importantly, there was a substantial increase in the percentage of slowly replicating forks in the DKO sample compared to that in the control sample (Fig. 4J). For example, there were six times as many forks with an estimated velocity of 1.4 kb/min or lower in the DKO embryo as in the control embryo (i.e., 60% versus 10%). These data, coupled with the increased DNA damage in DKO OrthoE (Fig. 4D and E), suggest the presence of replication fork stalling in these cells.

Inactivation of E2F2 rescues erythropoietic defects in DKO mice.

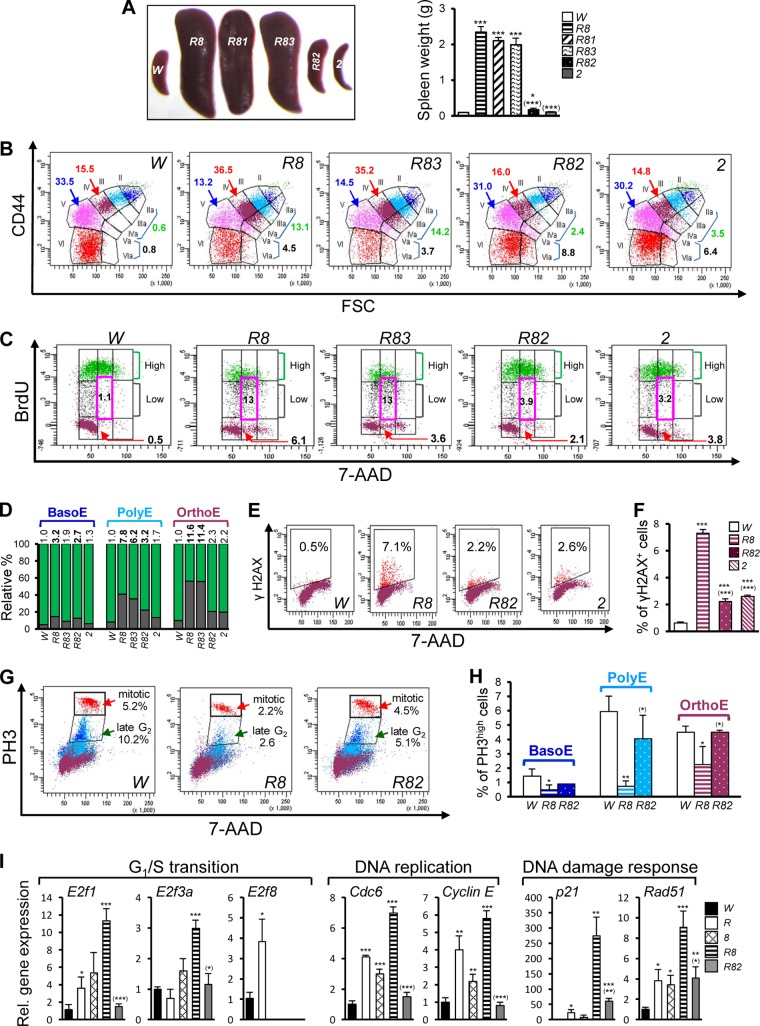

Given the massive E2F target gene activation in the DKO mice (Fig. 1), we sought to determine whether E2F1, E2F2, or E2F3 contributed to the global E2F target gene activation and the severe anemia that resulted from the Rb and E2F8 deficiencies. Using an Mx1-Cre-mediated, HSC-specific KO system to generate triple-KO (TKO) mice deficient for Rb, E2F8, and E2F1, E2F2, or E2F3, we found that although the loss of E2f1 had no obvious impact on the severe anemia and profound splenomegaly observed for the Rb; E2f8 DKO mice, the loss of E2f3 slightly suppressed such defects (Fig. 5A and Table 1). Importantly, the loss of E2f2 essentially rescued all the erythropoietic defects manifested in the DKO mice, as evidenced by increased hemoglobin levels, increased RBC levels, increased hematocrit, and attenuated splenomegaly (Fig. 5A and Table 1). In addition, CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging confirmed that the loss of E2f2 also rescued the erythroid differentiation defects observed in the DKO mice, as evidenced by the relatively normal percentages of OrthoE, Retic, RBC, and macrocytic nucleated erythroid cells (stages IIa to IVa) in the Rb; E2f2; E2f8 TKO mice (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the loss of E2f2 substantially suppressed all of the cell cycle defects in OrthoE of the DKO mice, including inefficient DNA replication (Fig. 5C and D), increased DNA damage (Fig. 5E and F), and reduced numbers of mitotic cells (Fig. 5G and H). Importantly, the aberrant upregulation of E2F target genes observed in the DKO mice was also reversed or suppressed by the E2f2 loss (Fig. 5I). It is worth noting that compared to control mice, the Rb; E2f2; E2f8 TKO mice exhibited several mild defects, such as fewer RBC, increased mean cell volume (MCV) for Retic and RBC, slightly increased numbers of BrdUlow cells, and slightly increased DNA damage (Fig. 5B to F and Table 1). However, these defects were most likely a consequence of the E2f2 loss, as E2f2−/− mice displayed defects similar to those displayed by the TKO mice (Fig. 5B to F and Table 1).

FIG 5.

Deletion of E2f2 rescues the erythropoietic defects observed in Mx1-Cre-mediated Rb;E2f8 DKO mice. (A) Representative images of spleens (left) and average spleen weight (right) of mice of the indicated genotypes (n ≥ 3). In all figures, “R81” indicates RbΔ/Δ; E2f8Δ/Δ; E2f1−/− mice, “R82” indicates RbΔ/Δ; E2f8Δ/Δ; E2f2−/− mice, “R83” indicates RbΔ/Δ; E2f8Δ/Δ; E2f3Δ/Δ mice, and “2” indicates E2f2−/− mice. Asterisks reflect P values for statistical comparisons to W mice, and asterisks in parentheses are P values for statistical comparisons to R8 mice. (B) Representative CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging flow cytometric plots of BM cells. Numbers represent the percentages of OrthoE (red), Retic (blue), macrocytic nucleated EB (green), and macrocytic enucleated erythroid cells (black). (C) Representative cell cycle profiles for OrthoE of BM cells from an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay and CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging. DNA profiles were gated as described in the legend of Fig. 4A. (D) Percentages of BrdUhigh (green) and BrdUlow (gray) cells from data in panel C (n = 2). Numbers above each bar represent average fold changes of the ratios of BrdUlow/BrdUhigh in the KO groups compared to those in W. (E and F) Representative flow cytometric plots of OrthoE (E) and quantifications (F) of γH2AX+ cells from BM cells (n = 3). (G and H) Representative flow cytometric plots (G) and quantifications (H) of BM cells showing mitotic cells (PH3high cells) and late-G2-phase cells (PH3low) (n = 3). (I) Relative gene expression measured by qRT-PCR analysis of Ter119+ CD71high EB for representative genes that are involved in the G1/S transition, DNA replication, and the DNA damage response (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

CBC analysis of hematological parameters of peripheral blooda

| Parameter | Mean value for mouse genotype ± SD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RbloxP/loxP | RbΔ/Δ E2f8Δ/Δ | RbΔ/Δ E2f8Δ/Δ E2f1−/− | RbΔ/Δ E2f8Δ/Δ E2f2−/− | RbΔ/Δ E2f8Δ/Δ E2f3Δ/Δ | E2f2−/− | |

| RBC (1012 cells/liter) | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 4.43 ± 0.4*** | 5.0 ± 0.1***(***) | 8.0 ± 0.6***(***) | 6.6 ± 1.4***(**) | 7.1 ± 0.4***(***) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 0.5*** | 8.4 ± 0.4*** | 14.7 ± 3.0(***) | 10.7 ± 2.5**(*) | 14.3 ± 1.4(***) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.4 ± 1.6 | 24.6 ± 1.5*** | 29.8 ± 4.4***(*) | 44.7 ± 3.0***(***) | 34.3 ± 8.0*(*) | 43.8. ± 5.4(***) |

| RDW (%) | 17.7 ± 0.9 | 25.7 ± 3.0*** | 21.5 ± 1.3* | 24.4 ± 2.0*** | 16.8 ± 4.2** | 26.4 ± 2.2** |

| MCV (fl) | 45.2 ± 2.0 | 54.6 ± 3.7*** | 59.3 ± 7.0*** | 56.3 ± 4.4*** | 52.0 ± 4.3 | 62.1 ± 7.3*** |

| MCH (pg) | 15.9 ± 0.9 | 17.9 ± 1.2** | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 17.8 ± 1.2** | 16.3 ± 1.2 | 20.3 ± 1.5***(*) |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 35.2 ± 1.4 | 32.1 ± 1.2*** | 28.3 ± 2.7***(*) | 29.8 ± 2.4*** | 31.3 ± 0.6*** | 32.8 ± 1.6* |

Shown are means ± standard deviations (n ≥ 3/genotypic group). RDW, red blood cell distribution width; MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean cell hemoglobin; MCHC, mean cell hemoglobin concentration. Asterisks represent P values for statistical comparisons to control (RbloxP/loxP or Mx1+/cre) mice, and asterisks in parentheses represent P values for statistical comparisons to RbΔ/Δ; E2f8Δ/Δ mice (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

It is important to note that since our microarray data were derived from the Ter119+ CD71high subpopulation, which includes ProE, BasoE, PolyE, and OrthoE, and since the loss of E2f2 rescued the OrthoE enrichment defect seen in DKO mice, the massive derepression of E2F target genes observed in DKO mice (Fig. 1A) and the reversal of such aberrant gene expressions in Rb; E2f2; E2f8 TKO mice (Fig. 5I) may result from the higher representation of OrthoE in the DKO samples if there were higher levels of gene expression in OrthoE than in the other three differentiation stages. However, two pieces of evidence suggest that this is very unlikely. First, qRT-PCR analysis of representative genes from various upregulated, enriched pathways using sorted BasoE, PolyE, OrthoE, and Retic from the BM of wild-type mice showed that transcripts of all analyzed genes except E2f2 were gradually downregulated during erythroid terminal differentiation (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). In addition, heat maps of representative genes (see Fig. S2A) were comparable to those generated by analyzing the equivalent raw gene expression data from FL cells from the Lodish group (45) (see Fig. S2B and C). Second, heat maps generated by analyzing the raw gene expression data from the Lodish group (45) for genes involved in representative upregulated pathways seen in the DKO mice indicated that almost all genes were downregulated in the late stages (i.e., R4 and R5) of erythroid terminal differentiation (see Fig. S2D).

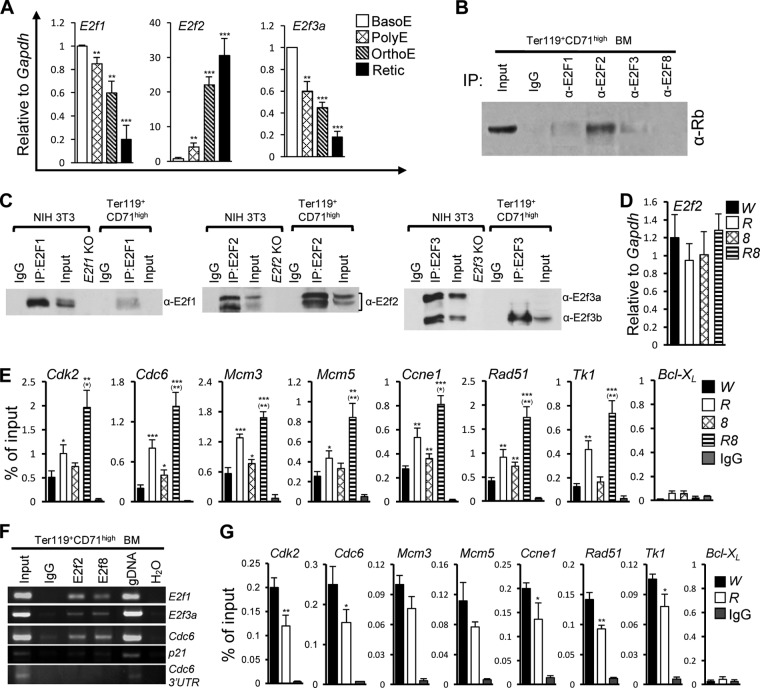

Loss of Rb and E2F8 synergizes to increase E2F2 binding to target gene promoters.

To understand why the loss of E2f2, but not the loss of E2f1 or E2f3, rescued the erythropoietic defects in DKO mice, we determined whether E2F2 was more abundant in late-stage EB from BM cells of wild-type mice than E2F1 and E2F3 by measuring mRNA levels of E2f1, E2f2, and E2f3a in sorted BasoE, PolyE, OrthoE, and Retic. We found that of the three E2Fs, E2F2 was the only E2F member whose mRNA levels increased in late-stage EB (Fig. 6A), consistent with data from a previous report on mouse FL cells (23). In line with this, among the three E2Fs, E2F2 was the most abundant E2F that is associated with Rb in erythroid progenitors (Fig. 6B). The lack of Rb binding by E2F1 or E2F3 in erythroid progenitors (Fig. 6B) is not due to inefficient pulldown by E2F1 or E2F3 antibodies, as E2F1 antibodies and E2F3 antibodies pulled down E2F1 and E2F3, respectively, in NIH 3T3 cells as efficiently as E2F2 antibodies pulled down E2F2 (Fig. 6C). Although neither E2F1 nor E2F3 antibodies pulled down much E2F1 or E2F3 protein in Ter119+ CD71high EB, this is most likely because of the relatively low abundances of E2F1 and E2F3 in these cells, as there was almost no detectable E2F1 or E2F3a in the input lysates (Fig. 6C, compare E2F levels in the “Input” lane with those in the corresponding “IP” lane).

FIG 6.

Loss of Rb and E2F8 synergizes to increase E2F2 binding to target gene promoters. (A) Relative gene expression levels of E2f1, E2f2, and E2f3a measured by qRT-PCR analysis in different stages of EB from BM of wild-type mice (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistical comparisons to BasoE (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (B and C) Immunoprecipitation of the indicated E2Fs from Ter119+ CD71high EB of wild-type BM cells or NIH 3T3 cells, followed by Western blots with the indicated antibodies. IgG served as a negative control for IP. “Input” represents lysates equivalent to 5% of the total lysates used for each IP. In panel C, IgG light-chain-specific secondary antibodies were used for Western blots, and lysates from various E2f KO NIH 3T3 cells served as negative controls for Western blots. (D) Relative gene expression levels of E2f2 in Ter119+ CD71high EB from BM of mice of the indicated genotypes using the Mx1-Cre-mediated KO system (n = 3). (E) E2F2 ChIP qPCR of E2F2 binding to representative E2F target gene promoters in Ter119+ CD71high EB from BM of different genotypic groups of mice using the Mx1-Cre-mediated KO system. Bcl-XL (a non-E2F-target gene) and IgG served as negative controls. (F) ChIP PCR analysis of Ter119+ CD71high wild-type BM cells. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as a positive control, whereas IgG and the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the Cdc6 gene were used as negative controls. (G) E2F8 ChIP qPCR of E2F8 binding to representative E2F target gene promoters in Ter119+ CD71high EB from BM of W and R mice using the Mx1-Cre-mediated KO system. Bcl-XL and IgG served as negative controls.

The striking suppression of erythropoietic defects in DKO mice by E2f2 loss prompted us to assess the possibility that Rb and E2F8 synergize to promote erythropoiesis by cosuppressing E2f2. Surprisingly, neither Rb nor E2F8 seems to transcriptionally regulate E2f2, as qRT-PCR analysis showed that the loss of Rb and/or E2f8 did not significantly increase E2f2 mRNA levels in Ter119+ CD71high EB (Fig. 6D). Intriguingly, despite the lack of transcriptional regulation of E2f2 by Rb or E2F8, qPCR of E2F2 ChIPs indicated that there was more E2F2 bound to E2f-binding sites on promoters of several representative E2F-responsive genes in Rb KO EB and the E2f8 KO EB than in control EB (Fig. 6E). Importantly, E2F2 occupancies at the target gene promoters were further enhanced synergistically in the DKO EB (Fig. 6E). These data raise the possibility that Rb and E2F8 synergize to downmodulate E2F2-mediated transcriptional activities. Consistent with this notion, in wild-type Ter119+ CD71high EB, E2F2 (but not E2F8) was found to be bound by Rb (Fig. 6B), and E2F2 and E2F8 co-occupied the promoter regions consisting of the E2f-binding site(s) of several target genes (Fig. 6F). In addition, the loss of Rb, which releases more free E2F2, led to reduced E2F8 occupancies in target gene promoters (Fig. 6G), suggesting that E2F2 competes with E2F8 for binding to target gene promoters.

DISCUSSION

As a potent tumor suppressor, Rb controls a key cell cycle checkpoint at the G1/S transition to prevent aberrant cell cycle entry and cancer (18, 46–49). At the cellular level, Rb inhibits DNA replication in an E2F-dependent manner (50). During normal development, Rb is thought to play a similar role in ensuring permanent cell cycle exit in terminally differentiating cells (16, 27, 29, 42). A hallmark phenotype of Rb deficiency in this setting is the increased S-phase population in cells that are programmed for permanent cell cycle exit and terminal differentiation. The increased percentage of S-phase cells, assessed by BrdU immunostaining, led to the notion that the inactivation of Rb triggers unscheduled DNA replication and untimely cell cycle entry. In the present study, however, we uncovered a previously unknown and unorthodox role of Rb in promoting DNA replication and cell cycle progression. Using a much-improved CD44-FSC-based erythroid staging system in combination with an in vivo BrdU incorporation assay, we were able to distinguish between the BrdUhigh subpopulation and the BrdUlow subpopulation, which would be difficult to discern by using the conventional BrdU immunostaining approach on tissue sections. We demonstrated that during erythroid terminal differentiation, inactivation of Rb led to progressively worsening cellular defects that culminated in OrthoE with inefficient DNA replication, increased DNA damage, and impaired cell cycle progression. Given that OrthoE are normally programmed to permanently exit the cell cycle, we propose that the increased S-phase fraction of Rb-deficient OrthoE is not only because of untimely S-phase entry but also a reflection of extended S phase resulting from stressed DNA replication and impaired S-phase progression, defects that were previously unknown to be associated with Rb deficiency. Importantly, all of these defects associated with Rb loss were exacerbated in the absence of E2F8, suggesting that E2F8 collaborates with Rb to promote erythropoiesis by preventing stressed DNA replication to ensure normal cell cycle progression. We speculate that inefficient DNA replication in Rb-deficient OrthoE resulted from a conflict between enforced cell cycle entry that is associated with aberrantly high levels of transcriptional activities and programmed cell cycle exit that renders the cellular machinery incompatible for unperturbed DNA replication. Interestingly, a recent report showed that in newly transformed human keratinocytes with an aberrantly activated Rb/E2F pathway, cellular nucleotide levels were significantly reduced, a defect that caused DNA replication stress and DNA damage, ultimately leading to genomic instability (51). Since the DNA metabolic process pathway was among the top five upregulated and enriched pathways in DKO mice, whether nucleotide imbalance or insufficiency contributes to stressed DNA replication in the untransformed, primary Rb KO or DKO erythroid cells warrants further investigation.

Early studies using mouse embryonic fibroblasts established a functional link between Rb and E2F1 to E2F3, as the inactivation of Rb leads to the release of these E2Fs that are bound and sequestered by functional Rb in quiescent cells (4, 5). Importantly, more recent work using in vivo mouse models demonstrated that E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3 activators can mediate Rb function in vivo (16, 22–29). In the erythroid lineage, we have shown that E2F2 plays a predominant role in mediating the synergy between Rb and E2F8, as the loss of E2f2 ameliorated essentially all of the erythropoietic defects observed in the DKO mice. While the precise mechanism underlying the rescue of the DKO phenotype by E2F2 loss remains to be addressed, it is possible that the loss of E2F2 simply rescues defects resulting from an Rb deficiency, thereby returning the situation in the Rb;E2f8 DKO mice to that in the E2f8 KO mice. We also showed that virtually all mild defects observed in the Rb; E2f2; E2f8 TKO mice were similar to those seen in the E2f2−/− mice, suggesting that while the loss of E2f2 rescues defects that resulted from Rb and E2F8 deficiencies, the loss of Rb and E2f8 does not mitigate the defects observed in the E2f2−/− mice. Consistent with an important role of E2F2 in erythroid terminal differentiation and in mediating the synergy between Rb loss and E2F8 loss, during embryogenesis, the inactivation of E2f2 led to cell cycle defects in FL erythroid cells but suppressed erythropoietic defects resulting from an Rb deficiency (23). The importance of E2F2 in regulating erythropoiesis is further supported by the recent finding that E2F2 forms a tricomplex with Rb and GATA1 that is required to stall cell proliferation and to promote erythroid terminal differentiation (52).

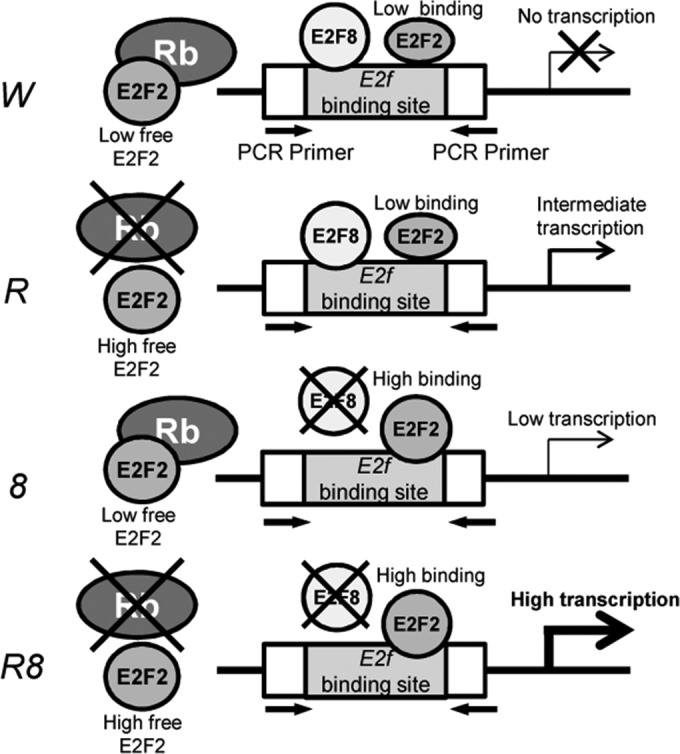

It has been well documented that Rb function depends largely on the transcriptional activities of E2Fs that have a pocket-protein-binding domain (16, 22–29). Our gene expression microarray data indicate that E2F8, an atypical E2F repressor that does not have a consensus pocket-protein-binding domain, synergizes with Rb to maintain the transcriptional repression of genes, as the inactivation of Rb and E2f8 led to a massive derepression of E2F-responsive genes, many of which were enriched for pathways related to the cell cycle defects observed in the DKO mice. To our knowledge, this is the first instance where a non-pocket-protein-binding E2F can synergize, at the molecular level, with Rb to impose potent transcriptional repression, despite the fact that the loss of E2f8 alone neither causes any measurable cellular defects nor incurs substantial derepression of E2F target genes. Interestingly, despite a lack of transcriptional regulation of E2f2 by Rb or E2F8, in the absence of Rb and/or E2F8, more E2F2 was recruited to E2f-binding sites of target gene promoters. These data, coupled with the data showing that E2F2 and E2F8 occupied the same E2f-binding sites on target gene promoters and that Rb deficiency led to reduced E2F8 binding to target gene promoters, strongly suggest that Rb and E2F8 synergize to promote erythroid terminal differentiation by preventing aberrant gene activations by E2F2 through the ability of Rb to bind/sequester E2F2 and the ability of E2F8 to compete with E2F2 for E2f-binding sites on target gene promoters. We propose a working model to explain how E2F8 functionally synergizes with Rb to prevent E2F2-mediated aberrant target gene activation and defective terminal differentiation (Fig. 7). In wild-type OrthoE, which are programmed to exit the cell cycle, Rb binds to and sequesters the activator E2F2, thereby preventing E2F2-mediated untimely transcriptional activation of target genes that are important for cell cycle entry. In addition, as a transcriptional repressor, E2F8 can compete with E2F2 for E2f-binding sites of target gene promoters, thereby further downmodulating E2F2-mediated aberrant transcriptional activation. In Rb-deficient OrthoE, while E2F2 is expected to be free from Rb binding and inhibition, E2F8 can compete with E2F2 for E2f-binding sites of target gene promoters, thereby minimizing E2F2-mediated upregulation of target genes and leading to mild defects in erythropoiesis. In E2F8-deficient OrthoE, Rb binding and inhibition of E2F2 may be sufficient to prevent aberrant activation of E2F target genes by E2F2, resulting in almost no erythropoietic defects. Importantly, in OrthoE deficient for both Rb and E2F8, both E2F2 suppression arms are lost: there is neither Rb to bind and sequester E2F2 nor E2F8 to compete with E2F2 for E2f-binding sites on target gene promoters, leading to uncontrolled, aberrant E2F2-mediated transcriptional activation of target genes. Taken together, our data provide a plausible and novel mechanism by which a non-pocket-protein-binding E2F can functionally synergize with a pocket protein to maintain transcriptional repression by cosuppressing aberrant transcriptional activities of E2F2.

FIG 7.

Working model of how Rb and E2F8 synergize to increase E2F2 binding to target gene promoters. Arrows depict primers used for ChIP PCR and ChIP qPCR.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Amgen for providing erythropoietin and Harvey Lodish and Joe Shuga for their help with the in vitro erythroid differentiation assay. We also thank Gustavo Leone and Alain de Bruin for providing the E2f8loxP/loxP mice, Ursula Klingmueller and James D. Engel for providing the EpoR-GFPCre mice, Kathleen McGrath and Scott Peslak for the ImageStream procedure, Utz Herbig for immunofluorescence staining, and Nury Yim, Dan Li, Lester Foldi, and Mai Abd Al Qader for technical assistance.

This study was supported by grants from the Leukemia Research Foundation, the New York Community Trust, and the Foundation of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01651-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hattangadi SM, Wong P, Zhang L, Flygare J, Lodish HF. 2011. From stem cell to red cell: regulation of erythropoiesis at multiple levels by multiple proteins, RNAs, and chromatin modifications. Blood 118:6258–6268. 10.1182/blood-2011-07-356006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinman RA. 2002. Cell cycle regulators and hematopoiesis. Oncogene 21:3403–3413. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walkley CR, Sankaran VG, Orkin SH. 2008. Rb and hematopoiesis: stem cells to anemia. Cell Div. 3:13. 10.1186/1747-1028-3-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyson N. 1998. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 12:2245–2262. 10.1101/gad.12.15.2245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nevins JR. 1998. Toward an understanding of the functional complexity of the E2F and retinoblastoma families. Cell Growth Differ. 9:585–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke AR, Maandag ER, van Roon M, van der Lugt NM, van der Valk M, Hooper ML, Berns A, te Riele H. 1992. Requirement for a functional Rb-1 gene in murine development. Nature 359:328–330. 10.1038/359328a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacks T, Fazeli A, Schmitt EM, Bronson RT, Goodell MA, Weinberg RA. 1992. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature 359:295–300. 10.1038/359295a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee EY, Chang CY, Hu N, Wang YC, Lai CC, Herrup K, Lee WH, Bradley A. 1992. Mice deficient for Rb are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and haematopoiesis. Nature 359:288–294. 10.1038/359288a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Bruin A, Wu L, Saavedra HI, Wilson P, Yang Y, Rosol TJ, Weinstein M, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2003. Rb function in extraembryonic lineages suppresses apoptosis in the CNS of Rb-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:6546–6551. 10.1073/pnas.1031853100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu L, de Bruin A, Saavedra HI, Starovic M, Trimboli A, Yang Y, Opavska J, Wilson P, Thompson JC, Ostrowski MC, Rosol TJ, Woollett LA, Weinstein M, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2003. Extra-embryonic function of Rb is essential for embryonic development and viability. Nature 421:942–947. 10.1038/nature01417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daria D, Filippi MD, Knudsen ES, Faccio R, Li Z, Kalfa T, Geiger H. 2008. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor is a critical intrinsic regulator for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells under stress. Blood 111:1894–1902. 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu T, Ghazaryan S, Sy C, Wiedmeyer C, Chang V, Wu L. 2012. Concomitant inactivation of Rb and E2f8 in hematopoietic stem cells synergizes to induce severe anemia. Blood 119:4532–4542. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankaran VG, Orkin SH, Walkley CR. 2008. Rb intrinsically promotes erythropoiesis by coupling cell cycle exit with mitochondrial biogenesis. Genes Dev. 22:463–475. 10.1101/gad.1627208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walkley CR, Shea JM, Sims NA, Purton LE, Orkin SH. 2007. Rb regulates interactions between hematopoietic stem cells and their bone marrow microenvironment. Cell 129:1081–1095. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iavarone A, King ER, Dai XM, Leone G, Stanley ER, Lasorella A. 2004. Retinoblastoma promotes definitive erythropoiesis by repressing Id2 in fetal liver macrophages. Nature 432:1040–1045. 10.1038/nature03068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel PL, Wu L, de Bruin A, Chong JL, Chen WY, Dureska G, Sites E, Pan T, Sharma A, Huang K, Ridgway R, Mosaliganti K, Sharp R, Machiraju R, Saltz J, Yamamoto H, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2007. Rb is critical in a mammalian tissue stem cell population. Genes Dev. 21:85–97. 10.1101/gad.1485307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bracken AP, Ciro M, Cocito A, Helin K. 2004. E2F target genes: unraveling the biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:409–417. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. 2009. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:785–797. 10.1038/nrc2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimova DK, Dyson NJ. 2005. The E2F transcriptional network: old acquaintances with new faces. Oncogene 24:2810–2826. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. 2002. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:11–20. 10.1038/nrm714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimarchi JM, Fairchild B, Wen J, Lees JA. 2001. The E2F6 transcription factor is a component of the mammalian Bmi1-containing polycomb complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:1519–1524. 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong JL, Tsai SY, Sharma N, Opavsky R, Price R, Wu L, Fernandez SA, Leone G. 2009. E2f3a and E2f3b contribute to the control of cell proliferation and mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:414–424. 10.1128/MCB.01161-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dirlam A, Spike BT, Macleod KF. 2007. Deregulated E2f-2 underlies cell cycle and maturation defects in retinoblastoma null erythroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:8713–8728. 10.1128/MCB.01118-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EY, Cam H, Ziebold U, Rayman JB, Lees JA, Dynlacht BD. 2002. E2F4 loss suppresses tumorigenesis in Rb mutant mice. Cancer Cell 2:463–472. 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00207-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee EY, Yuan TL, Danielian PS, West JC, Lees JA. 2009. E2F4 cooperates with pRB in the development of extra-embryonic tissues. Dev. Biol. 332:104–115. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parisi T, Yuan TL, Faust AM, Caron AM, Bronson R, Lees JA. 2007. Selective requirements for E2f3 in the development and tumorigenicity of Rb-deficient chimeric tissues. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:2283–2293. 10.1128/MCB.01854-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra HI, Wu L, de Bruin A, Timmers C, Rosol TJ, Weinstein M, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2002. Specificity of E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3 in mediating phenotypes induced by loss of Rb. Cell Growth Differ. 13:215–225 http://cgd.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/13/5/215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziebold U, Lee EY, Bronson RT, Lees JA. 2003. E2F3 loss has opposing effects on different pRB-deficient tumors, resulting in suppression of pituitary tumors but metastasis of medullary thyroid carcinomas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6542–6552. 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6542-6552.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziebold U, Reza T, Caron A, Lees JA. 2001. E2F3 contributes both to the inappropriate proliferation and to the apoptosis arising in Rb mutant embryos. Genes Dev. 15:386–391. 10.1101/gad.858801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinrich AC, Pelanda R, Klingmuller U. 2004. A mouse model for visualization and conditional mutations in the erythroid lineage. Blood 104:659–666. 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. 1995. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science 269:1427–1429. 10.1126/science.7660125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Ran C, Li E, Gordon F, Comstock G, Siddiqui H, Cleghorn W, Chen HZ, Kornacker K, Liu CG, Pandit SK, Khanizadeh M, Weinstein M, Leone G, de Bruin A. 2008. Synergistic function of E2F7 and E2F8 is essential for cell survival and embryonic development. Dev. Cell 14:62–75. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vooijs M, te Riele H, van der Valk M, Berns A. 2002. Tumor formation in mice with somatic inactivation of the retinoblastoma gene in interphotoreceptor retinol binding protein-expressing cells. Oncogene 21:4635–4645. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Zhang J, Ginzburg Y, Li H, Xue F, De Franceschi L, Chasis JA, Mohandas N, An X. 2013. Quantitative analysis of murine terminal erythroid differentiation in vivo: novel method to study normal and disordered erythropoiesis. Blood 121:e43–e49. 10.1182/blood-2012-09-456079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peslak SA, Wenger J, Bemis JC, Kingsley PD, Frame JM, Koniski AD, Chen Y, Williams JP, McGrath KE, Dertinger SD, Palis J. 2011. Sublethal radiation injury uncovers a functional transition during erythroid maturation. Exp. Hematol. 39:434–445. 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGrath KE, Bushnell TP, Palis J. 2008. Multispectral imaging of hematopoietic cells: where flow meets morphology. J. Immunol. Methods 336:91–97. 10.1016/j.jim.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuga J, Zhang J, Samson LD, Lodish HF, Griffith LG. 2007. In vitro erythropoiesis from bone marrow-derived progenitors provides a physiological assay for toxic and mutagenic compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:8737–8742. 10.1073/pnas.0701829104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu H, Maunakea AK, Martin MM, Huang L, Zhang Y, Ryan M, Kim R, Lin CM, Zhao K, Aladjem MI. 2013. Methylation of histone H3 on lysine 79 associates with a group of replication origins and helps limit DNA replication once per cell cycle. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003542. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Socolovsky M, Gross AW, Lodish HF. 2003. Role of Ras signaling in erythroid differentiation of mouse fetal liver cells: functional analysis by a flow cytometry-based novel culture system. Blood 102:3938–3946. 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishida S, Huang E, Zuzan H, Spang R, Leone G, West M, Nevins JR. 2001. Role for E2F in control of both DNA replication and mitotic functions as revealed from DNA microarray analysis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4684–4699. 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4684-4699.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huh MS, Parker MH, Scime A, Parks R, Rudnicki MA. 2004. Rb is required for progression through myogenic differentiation but not maintenance of terminal differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 166:865–876. 10.1083/jcb.200403004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wickramasinghe SN, Cooper EH, Chalmers DG. 1968. A study of erythropoiesis by combined morphologic, quantitative cytochemical and autoradiographic methods. Normal human bone marrow, vitamin B12 deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Blood 31:304–313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida Y, Todo A, Shirakawa S, Wakisaka G, Uchino H. 1968. Proliferation of megaloblasts in pernicious anemia as observed from nucleic acid metabolism. Blood 31:292–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong P, Hattangadi SM, Cheng AW, Frampton GM, Young RA, Lodish HF. 2011. Gene induction and repression during terminal erythropoiesis are mediated by distinct epigenetic changes. Blood 118:e128–e138. 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Classon M, Harlow E. 2002. The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:910–917. 10.1038/nrc950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeGregori J. 2004. The Rb network. J. Cell Sci. 117:3411–3413. 10.1242/jcs.01189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nevins JR. 2001. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10:699–703. 10.1093/hmg/10.7.699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van den Heuvel S, Dyson NJ. 2008. Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:713–724. 10.1038/nrm2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angus SP, Mayhew CN, Solomon DA, Braden WA, Markey MP, Okuno Y, Cardoso MC, Gilbert DM, Knudsen ES. 2004. RB reversibly inhibits DNA replication via two temporally distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:5404–5420. 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5404-5420.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bester AC, Roniger M, Oren YS, Im MM, Sarni D, Chaoat M, Bensimon A, Zamir G, Shewach DS, Kerem B. 2011. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell 145:435–446. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadri Z, Shimizu R, Ohneda O, Maouche-Chretien L, Gisselbrecht S, Yamamoto M, Romeo PH, Leboulch P, Chretien S. 2009. Direct binding of pRb/E2F-2 to GATA-1 regulates maturation and terminal cell division during erythropoiesis. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000123. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.