Abstract

Mitochondrial calcium uptake stimulates bioenergetics and drives energy production in metabolic tissue. It is unknown how a calcium-mediated acceleration in matrix bioenergetics would influence cellular metabolism in glycolytic cells that do not require mitochondria for ATP production. Using primary human endothelial cells (ECs), we discovered that repetitive cytosolic calcium signals (oscillations) chronically loaded into the mitochondrial matrix. Mitochondrial calcium loading in turn stimulated bioenergetics and a persistent elevation in NADH. Rather than serving as an impetus for mitochondrial ATP generation, matrix NADH rapidly transmitted to the cytosol to influence the activity and expression of cytosolic sirtuins, resulting in global changes in protein acetylation. In endothelial cells, the mitochondrion-driven reduction in both the cytosolic and mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio stimulated a compensatory increase in SIRT1 protein levels that had an anti-inflammatory effect. Our studies reveal the physiologic importance of mitochondrial bioenergetics in the metabolic regulation of sirtuins and cytosolic signaling cascades.

INTRODUCTION

Cells respond to environmental cues largely through receptor-mediated pathways that facilitate Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular endoplasmic reticulum stores (1). Once released into the cytosol, Ca2+ drives energy-intensive signaling pathways that evoke a cellular response. In parallel, Ca2+ is sequestered by functional mitochondria to speed ATP generation (2). Thus, a Ca2+-mediated rise in bioenergetics increases mitochondrial energy production to match cellular energy demand. Imbalances in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling disrupt this delicate balance and over time, manifest as pathogenic processes that contribute to human disease (3).

Mitochondria have a unique ability to decode and transduce cytosolic Ca2+ signals into an energetic output (ATP) to match cellular energetic demand. Specifically, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake regulates bioenergetics both by increasing the supply of reducing equivalents (NADH production) to the electron transport chain and by increasing F1-Fo ATP synthase activity (NADH consumption) (4, 5). The balance between NADH production and NADH oxidation is therefore exquisitely dependent upon both the shape and duration of the mitochondrial Ca2+ signal to activate NADH-generating matrix enzymes, as well as the rate of NADH consumption by the respiratory chain (6). Indeed, a single cytosolic Ca2+ event or sustained Ca2+ increase stimulates a mitochondrial NADH transient that diminishes as NADH is consumed by the respiratory chain (7). Repetitive Ca2+ events conversely trigger a persistent elevation in the NADH signature that reflects a dynamic relationship between Ca2+-stimulated NADH production and respiratory chain activity (8).

As opposed to NADH production, the consumption of NADH by the respiratory chain is related to the cell's energetic demand and depends on metabolic preference (glycolytic or oxidative) and substrate supply to mitochondria (6), as well as sufficient quantities of oxygen and ADP (9). However, the coordination between NADH production and NADH consumption was delineated largely in metabolic cells with robust mitochondrial activity. Many cell types, such as leukocytes (10) and vascular endothelial cells (ECs) (11), have low basal energy requirements and generate ATP primarily through anaerobic mechanisms outside the mitochondria. Nonetheless, endothelial mitochondria rapidly sequester cytosolic Ca2+ transients to influence vascular function (12). Repetitive Ca2+ oscillations are commonly observed in ECs (13–15) and influence NF-κB transcriptional activity (16) and expression of vascular adhesion molecules and interleukins (17, 18). Whether Ca2+-mediated alterations in mitochondrial bioenergetics can influence Ca2+-regulated cytosolic signaling cascades is unclear.

In the present study, we delineate a fundamental mechanism by which repetitive Ca2+ signals influence mitochondrial bioenergetics and intracellular signaling independent of ATP generation. Continual Ca2+ transients enhance mitochondrial Ca2+ loading and result in a persistent elevation in matrix NADH. Using primary human ECs as a model system, we demonstrate that Ca2+-stimulated mitochondrial NADH generation is shuttled to the cytosol as a bioenergetic cue to influence signaling. Specifically, mitochondrion-to-cytosol NADH transmission influences the expression of sirtuins, resulting in altered protein acetylation and cellular activation. Thus, matrix NADH metabolism is a key rheostat by which mitochondria integrate and decode cytosolic Ca2+ signals to influence cytosolic signaling cascades and nuclear gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) (Invitrogen) were cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions and used between passages 5 and 10. AD-293 cells (Stratagene) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. J774 macrophages (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. For plasmid expression experiments, HPAECs were transfected with 0.25 μg DNA using the Neon electroporation system (Invitrogen). The AD-293 calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) stable clone was generated by transfection (Lipofectamine 2000) with a Flag-CaSR plasmid followed by G418 selection. To reduce confluence-dependent variability in the NAD+/NADH ratio and sirtuin activities, all experiments were performed on confluent cells plated 2 to 3 days before assays.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10 mM nicotinamide and 10 μM trichostatin A for acetylation experiments. For Western blotting, 25 μg proteins was electrophoresed on NuPAGE 4 to 12% Bis-Tris acrylamide gels (Invitrogen), transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and probed with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. For immunoprecipitation, 2 mg cell lysate was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with A/G Plus agarose beads (Santa Cruz). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific) were used for detection.

Cellular respiration.

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured using the XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). HPAECs were plated in Seahorse 24-well assay plates, 30,000 cells/well, in M200 growth medium 48 h before the assay. OCR and ECAR measurements were performed in XF assay medium (Seahorse Bioscience) at 10-min intervals.

Intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) imaging.

Cells plated on MatTek dishes were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2 AM; Molecular Probes) in ECM buffer (120 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM Na-HEPES, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 2.0% bovine serum albumin [BSA] [pH 7.4]), with 100 μM sulfinpyrazone and 0.003% pluronic acid for 30 min at room temperature. After dye loading, cells were washed and imaged in ECM buffer with 0.25% BSA and 100 μM sulfinpyrazone using a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope calibrated for Fura-2 fluorescence (Molecular Probes). Spectral analysis of Ca2+ oscillations was measured as described previously (19). Mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) changes were measured with the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based genetically encoded mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator Cameleon D3cpv (Addgene plasmid 36324) (20). Images were acquired every 10 s with an LSM510 META Zeiss confocal microscope using a Fluar 40×/1.3 oil objective at 405/488 nm excitation/emission. Ratio images were obtained by dividing the intensity of the FRET channel to the intensity of the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) channel. The sensor response was calibrated at the end of the experiment for each cell by measuring Rmin (5 μM ionomycin and 5 mM EGTA) and Rmax (5 μM ionomycin and 5 mM CaCl2) (21).

NADH and NAD+/NADH ratio measurements.

Mitochondrial NADH fluorescence was measured with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a xenon arc lamp and DeltaRamX monochromator (Photon Technology International) and an Evolve 512 electron-modifying charge-coupled-device (EMCCD) camera (Photometrics) with the assistance of EasyRatioPro software using a UV filter. Specificity for mitochondrial NADH was determined by colocalization with the mitochondrial dye MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen).

Cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio was measured using the genetically encoded ratiometric fluorescence indicator Peredox (Addgene plasmid 32383) (22). Green and red fluorescence images were acquired every 20 s with an LSM510 META Zeiss confocal microscope using a Fluar 40×/1.3 oil objective at excitation wavelengths of 405 nm and 543 nm. Images were background corrected, and green-to-red ratio images were obtained using ImageJ software. For each cell, ratio data were normalized to the minimal green-to-red ratio signal obtained with 10 mM pyruvate. For quantitative measurements, the Peredox sensor was calibrated in ECM buffer without glucose by changing extracellular concentrations of lactate and pyruvate as previously described (23). Total intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio was measured using the EnzyChrom NAD+/NADH assay kit (BioAssay Systems). Intracellular lactate and pyruvate concentrations were measured using the lactate assay kit and pyruvate assay kit (Cayman Chemical) and used to calculate the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio (24).

Leukocyte adhesion assay.

HPAECs were plated into 96-well plates and cultured until confluent. J774 macrophages were stained with 1 μM Cell Tracker Green (Molecular Probes) for 0.5 h at 37°C. A total of 3 × 105 macrophages were placed on top of HPAECs and allowed to adhere to endothelial cells for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed vigorously with HBSS, and the fluorescence of adherent J774 macrophages was measured using a Synergy 4 fluorescence plate reader (BioTek) at 490-nm excitation and 525-nm emission wavelengths. Images of J774 macrophages adherent to HPAECs were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a 10× objective and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter.

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of mRNA expression was performed using a Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) on cDNAs synthesized using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen) from previously purified mRNA (RNeasy minikit; Qiagen).

ATP content.

ATP levels were measured using the EnzyLight assay kit (BioAssay Systems).

Statistical analysis.

The data are shown as means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs) from 3 or more independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using Student's t test, and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reagents.

Pan-acetylated lysine, SIRT2 (sirtuin 2), SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, p53, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), actin, histone H3, and acetyl-histone H3 antibodies were from Cell Signaling. SIRT1 and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) antibodies were from Invitrogen.

RESULTS

Receptor-mediated Ca2+ oscillations stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ loading in primary human pulmonary artery endothelial cells.

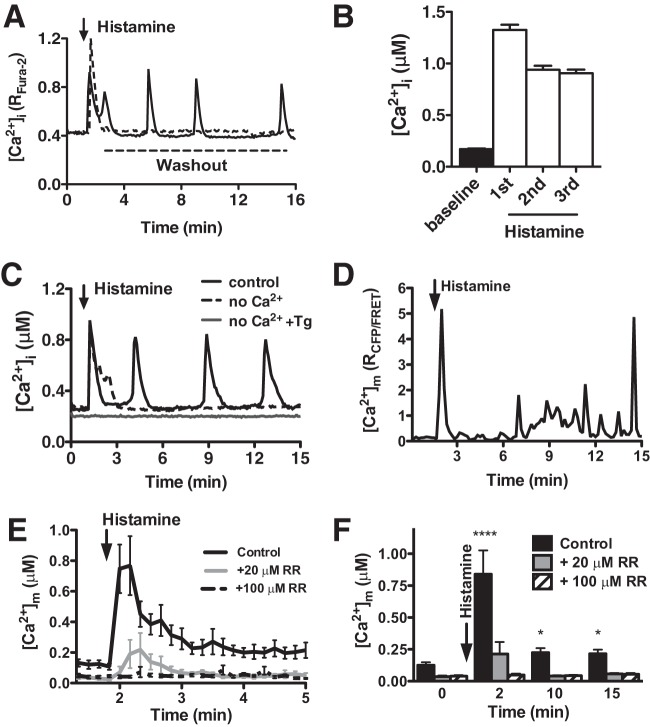

Oscillatory Ca2+ waves are a common event in both excitable and nonexcitable cells and control processes ranging from fertilization to cell death (25). The inflammatory agonist histamine activates ECs by initiating repetitive Ca2+ signals (26) that regulate vascular permeability, leukocyte recruitment, and vasomotor tone (27). In primary human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs), histamine (100 nM) triggered a rapid mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) that presented as an oscillatory pattern for as long as histamine was present in the extracellular environment (Fig. 1A). Kinetically, [Ca2+]i oscillations rose rapidly from 0.171 ± 0.006 μM at rest to an initial amplitude of 1.155 ± 0.05 μM that decreased slightly but remained consistent during subsequent transients (Fig. 1B). While the biophysical patterning of the histamine-induced Ca2+ response was heterogeneous over a wide range of concentrations, a majority of cells between 100 nM and 500 nM histamine exhibited oscillations with a mean frequency of ∼2 mHz (Table 1). At histamine concentrations below 100 nM, the [Ca2+]i response was comprised primarily of a single transient. Conversely, histamine at 1 μM resulted in a single [Ca2+]i event that decreased but remained elevated ∼50% over baseline (“plateau”). Mechanistically, histamine triggered an initial release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum that required sufficient extracellular Ca2+ to refill the intracellular stores and sustain the oscillatory phenotype (Fig. 1C and Table 1). Mitochondria are important buffers that uptake and release cytosolic Ca2+ and in doing so, dramatically shape intracellular Ca2+ signaling patterns (28). To evaluate the effects of [Ca2+]i oscillations on mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) was measured via confocal microscopy using the FRET-based genetically encoded mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator Cameleon D3cpv (20). Cameleon D3cpv measurements of [Ca2+]m showed a rapid and significant increase in matrix Ca2+ that coincided with the first histamine-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transient (i.e., initial release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores) (Fig. 1D). Although the simultaneous measurement of both cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ was not possible using the Cameleon D3cpv indicator, [Ca2+]m exhibited a heterogeneous response that presented as repetitive [Ca2+]i transients (i.e., oscillations). While these individual transients are masked when averaging all cells in the field, mean [Ca2+]m was higher at any time point after histamine stimulation (Fig. 1E and F). Biophysically, [Ca2+]m rose from 0.126 ± 0.022 μM at baseline to 0.839 ± 0.186 μM immediately after histamine treatment and then decreased to 0.224 ± 0.035 μM and remained statistically elevated at later time points. This finding suggests that repetitive mitochondrial Ca2+ loading serves to persistently elevate Ca2+ over baseline. Inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake with the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter blocker Ruthenium Red significantly decreased the amplitude of the first [Ca2+]m transient in a dose-dependent manner and abolished the subsequent elevation in [Ca2+]m following histamine stimulation (Fig. 1E and F) with no effect on [Ca2+]i oscillatory pattern (data not shown). Together, these results show synchronized mitochondrial Ca2+ loading during histamine-induced cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations that effectively serve to elevate matrix Ca2+ content.

FIG 1.

Receptor-mediated Ca2+ oscillations stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ loading in primary endothelial cells. (A) Single-cell oscillatory [Ca2+]i mobilization pattern in a representative HPAEC stimulated with histamine (100 nM) as demonstrated by the raw Fura-2 ratio. The addition of histamine is indicated by the arrow. Removal of histamine (washout) after 15 s eliminates the development of Ca2+ oscillations. (B) Fura-2 AM quantification of [Ca2+]i in HPAECs at baseline and after treatment with histamine (100 nM) (during the first, second, and third [Ca2+]i transients) (mean plus standard error of the mean [SEM] [error bar]; n = 109). (C) Representative single-HPAEC [Ca2+]i mobilization response to histamine in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and in which the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store was predepleted with thapsigargin (Tg) (1 μM) for 20 min prior to the histamine addition. (D) Oscillatory [Ca2+]m transients in a representative single cell as assessed by the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor Cameleon D3cpv and represented as the CFP/FRET ratio after histamine stimulation (100 nM). (E) Mean calibrated [Ca2+]m of HPAECs during histamine addition (100 nM). Data are shown as means ± SEMs from control cells (n = 31) and those pretreated with Ruthenium Red (RR) (20 μM, n = 26; 100 μM, n = 37). (F) Calibrated [Ca2+]m at the indicated time intervals in control cells and those pretreated with 20 μM and 100 μM Ruthenium Red. The values that are significantly different by Student's t test are indicated by asterisks as follows: ****, P < 0.0001; *, P < 0.05.

TABLE 1.

Percentage of responding HPAECs and corresponding mean frequency of calcium oscillations in response to increasing doses of histamine

| Buffer and histamine concn (nM) | % HPAECs (mean ±SEM) showing: |

Frequency (mHz) (mean ± SEM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Ca2+ transient | Ca2+ oscillations | Ca2+ plateau | ||

| Ca2+-containing buffer | ||||

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 | 30 ± 10 | 45 ± 10 | 2.5 ± 2.5 | 1.48 ± 0.18 |

| 100 | 21.56 ± 8.44 | 67.78 ± 4 | 8.9 ± 5.88 | 2.74 ± 0.18 |

| 300 | 24.17 ± 19.61 | 45.31 ± 16.55 | 27.07 ± 10.9 | 2.44 ± 0.25 |

| 500 | 14.8 ± 7.78 | 45.94 ± 7.85 | 39.26 ± 7.6 | 2.15 ± 0.13 |

| 1,000 | 16.71 ± 3.78 | 17.34 ± 3.36 | 65.95 ± 7.13 | 1.45 ± 0.09 |

| Ca2+-free buffer | ||||

| 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100 | 27.82 ± 2.62 | 2.16 ± 1.26 | 0 | 0.24 ± 0.08 |

| 300 | 79.67 ± 3.67 | 2.67 ± 1.45 | 0 | 0.64 ± 0.01 |

| 500 | 91.3 ± 8.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.06 ± 0.05 |

| 1,000 | 89.6 ± 10.4 | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 0 | 1.09 ± 0.05 |

Sustained mitochondrial Ca2+ loading regulates mitochondrial NADH accumulation.

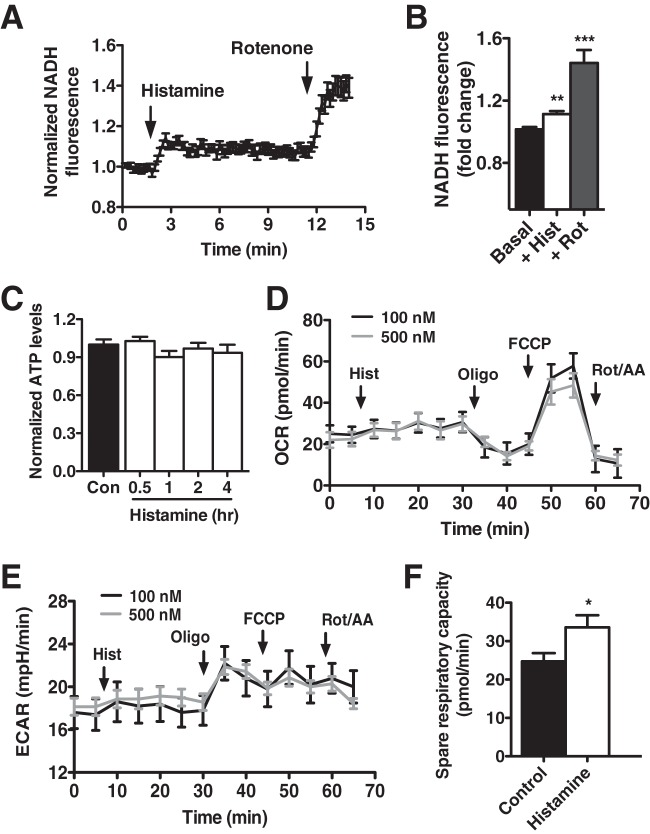

Mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ activates the Ca2+-sensitive enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (2) to speed mitochondrial NADH production (7, 29). Indeed, the histamine-induced elevation in matrix Ca2+ triggered a significant and sustained mitochondrial NADH accumulation (+11.4% ± 0.02% with respect to baseline) as measured by time course fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A and B) that was maximized by the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone. In energetic tissue, NADH funnels electrons into the respiratory chain to drive oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis (30). However, endothelial cells are largely glycolytic and do not rely on mitochondria as primary energy generators (31). We estimated that approximately 60% of intracellular ATP production was derived via glycolytic mechanisms and that histamine challenge did not change the relative contribution of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (data not shown). In support, histamine treatment did not increase total cellular ATP production in HPAECs (Fig. 2C). Similarly, HPAECs exhibited a low basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) that was unaffected by histamine stimulation as measured with a Seahorse analyzer (Fig. 2D). Likewise, Seahorse measurements of the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) showed no change in the glycolytic flux after histamine (Fig. 2E). The accumulation of NADH in response to histamine did, however, coincide with an enhanced spare respiratory capacity measured upon trifluorocarbonylcyanide phenylhydrazine (FCCP)-mediated uncoupling as the difference between carbonilcyanide FCCP -stimulated and basal OCR (Fig. 2F).

FIG 2.

Matrix Ca2+ regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics. (A) Time course fluorescence microscopy of mitochondrial NADH autofluorescence upon stimulation of HPAECs with histamine (100 nM) and rotenone (2 μM). NADH autofluorescence was normalized to baseline. (B) Quantification of changes in NADH autofluorescence of HPAECs upon the addition of histamine (+Hist) (100 nM) and rotenone (+Rot) (2 μM) (n = 147 cells). (C) ATP content of HPAECs at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h after histamine stimulation (100 nM). Values are normalized to baseline ATP content. (D) Representative traces of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of HPAECs upon sequential additions of histamine (100 nM or 500 nM), oligomycin (Oligo) (1 μM), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone and antimycin (Rot/AA) (1 μM each) using a Seahorse XF24 analyzer. (E) Seahorse X24 measurement of the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of HPAECs upon sequential addition of histamine (100 nM or 500 nM), oligomycin (1 μM), FCCP (1 μM), and rotenone and antimycin A (1 μM each). (F) Spare respiratory capacity of control and histamine-treated HPAECs as measured upon addition of FCCP (1 μM) with a Seahorse XF24 analyzer. Values represent the means from three independent experiments ± SEMs. The values that are significantly different by Student's t test are indicated by asterisks as follows: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial NADH metabolism transmits to the cytosol.

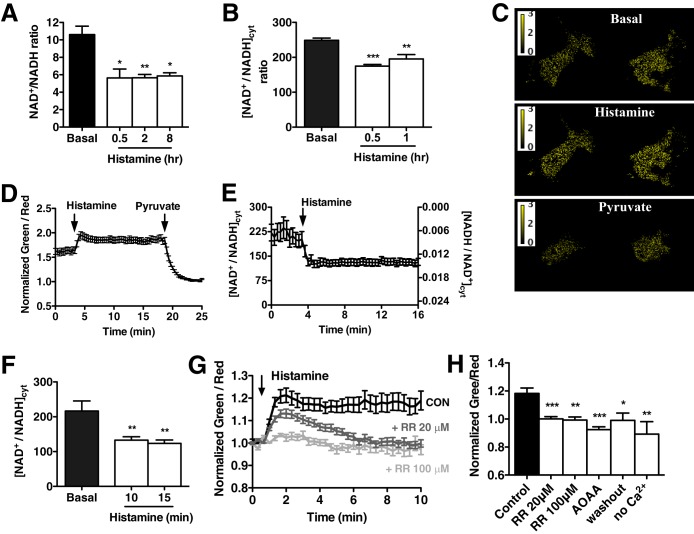

While not coupled to energy production, histamine-stimulated NADH production did manifest as a significant and persistent reduction in the total cellular NAD+/NADH ratio (53% ± 0.096%, up to 8 h after histamine treatment) (Fig. 3A). The depressed NAD+/NADH ratio was mostly due to an increase in NADH, since NAD+ levels did not significantly change (data not shown). The ratio between reduced NADH and oxidized NAD+ regulates the intracellular redox state and controls the activity of several enzymes and transcription factors (32). However, the relative impermeability of the mitochondrial inner membrane dictates that NAD+ and NADH are highly compartmentalized, with approximately 75% of cellular NAD+/NADH confined within the mitochondria (33). To our knowledge, there is no evidence that Ca2+-mediated increases in mitochondrial NADH influence cytosolic NAD+/NADH homeostasis.

FIG 3.

Mitochondrial NADH metabolism transmits to the cytosol. (A) Total intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio measured in HPAECs at baseline and at 0.5, 2, and 8 h after stimulation with histamine (100 nM). (B) Cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio calculated from the measured lactate/pyruvate ratio in HPAECs at baseline and at 0.5 and 1 h after histamine treatment (100 nM). Values in panels A and B are mean from 3 independent experiments plus SEMs (error bars). (C) Representative pseudocolored green-to-red fluorescence ratio images of HPAEC expressing the Peredox sensor at baseline and after treatment with histamine (100 nM) and pyruvate (10 mM). (D) Representative time course of green-to-red fluorescence ratio of HPAECs expressing Peredox after treatment with 100 nM histamine and 10 mM pyruvate. Fluorescence ratio was normalized to the values obtained in the presence of pyruvate alone. Values are means ± SEMs from six cells in the field. (E) Time course of cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) calculated from the Peredox green-to-red fluorescence ratio after sensor calibration. (F) Cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio values measured with Peredox in HPAECs at baseline and at 10 and 15 min after histamine treatment. Values are means ± SEMs from 26 cells from three independent experiments. (G) Dose-dependent decrease in Peredox green-to-red fluorescence in response to Ruthenium Red (RR) (20 μM and 100 μM). Fluorescence ratio was normalized to baseline values for comparison. CON, control. (H) Peredox green-to-red fluorescence 10 min after histamine stimulation in the presence of RR (20 μM and 100 μM) and AOAA (500 μM), and when Ca2+ oscillations were ceased by histamine washout and by the absence of Ca2+ in the experimental buffer. Fluorescence ratio was normalized to baseline values for comparison. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

While NADH is not actively exported from the mitochondrial matrix, it is possible that persistent NADH buildup facilitates the transmission of reducing equivalents from the matrix to the cytosol through redox shuttles (34). We therefore calculated the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio ([NAD+/NADH]cyt) by measuring the concentrations of lactate and pyruvate, which are linked by NADH-dependent lactate dehydrogenase (24). Similar to the total NAD+/NADH ratio, histamine treatment resulted in a 30% ± 0.019% reduction in [NAD+/NADH]cyt, decreasing from 248.7 ± 6.482 to 175 ± 4.638 at 0.5 h after histamine stimulation (Fig. 3B). To directly measure the dynamics of [NAD+/NADH]cyt, HPAECs were transfected with the genetically encoded ratiometric indicator Peredox (22) and visualized via confocal microscopy. Changes in the green-to-red fluorescence ratio of the sensor are directly related to changes in the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, and quantitative measurements of the ratio can be obtained after sensor calibration with exogenous lactate and pyruvate (23). Histamine treatment resulted in a rapid increase in the green-to-red ratio of Peredox that remained elevated throughout the experiment and was consistent with an increase in the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ (decrease in the cytosolic NAD+/NADH) (Fig. 3C and D). Quantitation of [NAD+/NADH]cyt showed significantly decreased [NAD+/NADH]cyt from 235 ± 38.27 at baseline to 129 ± 21.08 15 min after histamine challenge similar to values estimated from lactate and pyruvate measurement (Fig. 3E and F). Importantly, the changes in [NAD+/NADH]cyt were related to the Ca2+-induced mitochondrial NADH increase, since blocking mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake with Ruthenium Red abolished the decrease in [NAD+/NADH]cyt upon histamine treatment (Fig. 3G and H) in a dose-dependent manner consistent with mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 1E and F). Likewise, limiting the histamine response to a single Ca2+ transient either by histamine washout or by removing extracellular Ca2+ resulted in a normalization of the [NAD+/NADH]cyt, conclusively demonstrating that repetitive transients are required to maintain a reduced [NAD+/NADH]cyt. Further, while Ruthenium Red inhibited the ability of mitochondrial bioenergetics to alter the [NAD+/NADH]cyt, it did not appreciably alter the histamine oscillatory response (data not shown). These data are important in that they prove that the cytosolic alterations in NADH originate within the mitochondria and are not simply occurring in parallel with mitochondrial bioenergetics. Inhibition of the malate-aspartate shuttle using aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA) also prevented the persistent alteration in the [NAD+/NADH]cyt, suggesting that mitochondrial redox shuttles relay acute NADH changes to the cytosol (Fig. 3H). We observed that inhibition of both the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and malate/aspartate shuttle resulted in a more reduced cytosolic NADH-NAD+ redox state at baseline, consistent with a decrease in basal mitochondrial metabolism. Indeed, a reduction in mitochondrial Ca2+ loading was detected at baseline in the presence of Ruthenium Red (Fig. 1E and F) that might relate to lessened mitochondrial function. Similar to ECs, an AOAA-mediated increase in the cytosolic NADH/NAD ratio has been reported in vascular smooth muscle cells due to impaired removal of cytosolic reducing equivalents through the malate/aspartate shuttle and reduced oxidative metabolism (35).

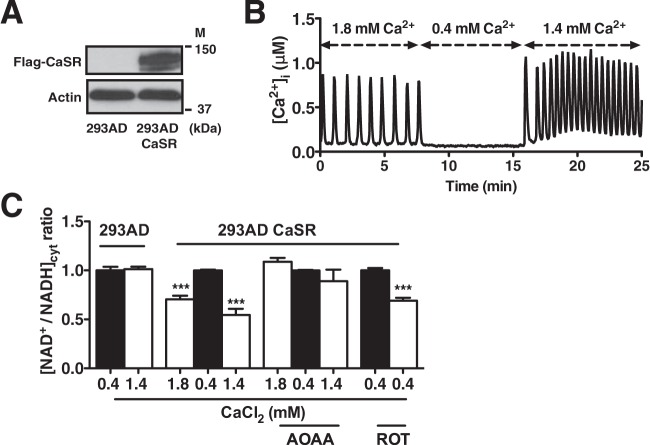

Oscillating 293AD CaSR cells show changes in [NAD+/NADH]cyt.

To verify that the communication between mitochondrial and cytosolic NAD+/NADH metabolism was not restricted to endothelial cells, we employed an alternative cell model of inducible Ca2+ oscillations. 293AD cells were transfected with the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) (Fig. 4A), a G-protein-coupled receptor normally absent in 293AD cells (36). When cultured in media containing less than 0.4 mM Ca2+, 293AD CaSR cells do not exhibit baseline Ca2+ signaling. However, bolus addition of extracellular CaCl2 triggers rapid and repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in CaSR-expressing cells (Fig. 4B). Concomitant with Ca2+ oscillations, the 293AD CaSR line exhibited a significant decrease in the [NAD+/NADH]cyt that was absent in nontransfected 293AD cells (Fig. 4C). As the cessation of oscillations restored the [NAD+/NADH]cyt, it is likely that the reversible malate-aspartate shuttle is activated by Ca2+-stimulated mitochondrial bioenergetics. Indeed, similar to HPAECs, AOAA preincubation in 293AD CaSR cells rendered the [NAD+/NADH]cyt insensitive to oscillations. Interestingly, stimulation of mitochondrial NADH accumulation by the respiratory chain inhibitor rotenone also lowered the [NAD+/NADH]cyt in nonoscillating 293AD CaSR, suggesting that a Ca2+-independent rise in mitochondrial NADH can also influence cytosolic NAD+/NADH metabolism. In total, these findings are the first to reveal that Ca2+-induced alterations in mitochondrial bioenergetics are actively communicated to the cytosol, likely by the reversible malate-aspartate shuttle.

FIG 4.

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ oscillations in 293AD CaSR cells result in decreased cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio. (A) Immunoblot analysis of CaSR overexpression in 293AD cells transfected with Flag-CaSR DNA. The positions of molecular mass markers (M) are indicated. (B) [Ca2+]i measured by Fura-2 AM in 293AD CaSR under extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. (C) Cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio calculated from the measured lactate/pyruvate ratio in 293AD CaSR cells in the presence of high (1.8 to 1.4 mM) and low (0.4 mM) CaCl2 concentrations in the presence and absence of aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA) (2 mM) and after 30-min treatment with rotenone (2 μM). Values are normalized to low CaCl2 293AD CaSR cells and are the means from three independent experiments plus SEMs. ***, P < 0.001.

Mitochondrial regulation of NAD+/NADH metabolism alters protein acetylation and sirtuin expression.

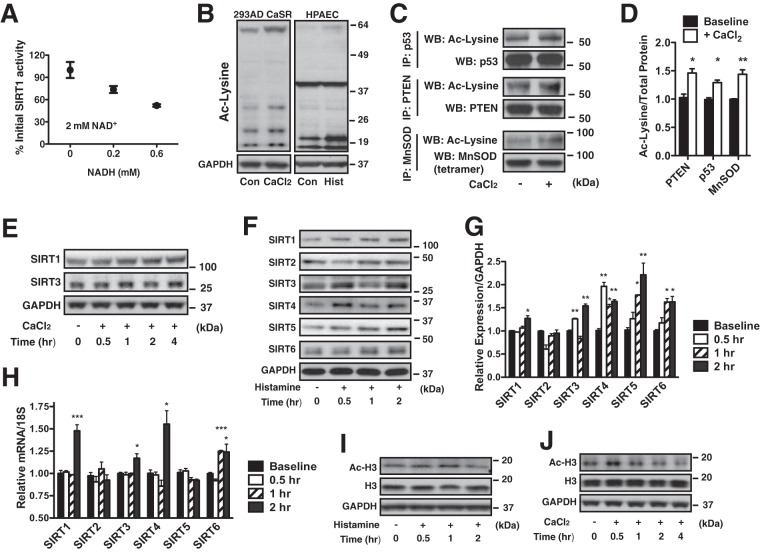

In both the mitochondrial and cytosolic compartments, NAD+/NADH metabolism coincides with alterations in the activity of NAD+-dependent deacetylase enzymes known as sirtuins (37). In general, a reduced [NAD+/NADH]cyt regulates the activity of SIRT1 to deacetylate protein lysine residues (38, 39). Indeed, in vitro deacetylase activity of cytosolic and nuclear localized SIRT1 exhibited an inverse relationship with NADH concentrations that corresponded to ratios measured in histamine-stimulated HPAECs (Fig. 5A). Since the activity of sirtuins influences protein acetylation, total lysine acetylation was evaluated in HPAECs and 293AD CaSR cells under reduced [NAD+/NADH]cyt conditions. Both histamine challenge (HPAECs) and CaCl2 stimulation (293AD CaSR) resulted in an overall increase in protein acetylation (Fig. 5B). To determine whether acetylation was confined to the mitochondria, prominent cytosolic and mitochondrial protein targets of sirtuins were selected for individual acetylation analysis: phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), p53, and MnSOD (40). Calcium oscillations were initiated in 293AD CaSR cells for 0.5 h, and endogenous PTEN and p53 (nuclear-cytosolic localization) and MnSOD (mitochondrial) were immunoprecipitated and probed for lysine acetylation. At high CaCl2 (decreased [NAD+/NADH]cyt), PTEN, p53, and MnSOD demonstrated increased acetylation (Fig. 5C and D). These data are the first to demonstrate that mitochondrial Ca2+ loading rapidly influences protein acetylation, likely via a buildup of NADH and the inhibition of sirtuin enzymatic activity.

FIG 5.

Mitochondrial regulation of NAD+/NADH metabolism alters protein acetylation and sirtuin expression. (A) In vitro measurement of SIRT1 deacetylase activity in the presence of 2 mM NAD+ and increasing concentrations of NADH (0 to 0.6 mM). (B) Representative Western blot of extracts of 293AD CaSR cells grown in CaCl2 (final concentration of 1.4 mM for 0.5 h) and HPAECs in the presence or absence of histamine (Hist) (100 nM, 0.5 h). The extracts were probed with a pan-acetyllysine (Ac-Lysine) antibody and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. Con, control. (C) Western blot (WB) analysis of PTEN, p53, and MnSOD (tetramer) acetylation immunoprecipitated (IP) from 293AD CaSR cells at low (0.4 mM) (−) and high (1.4 mM) (+) CaCl2 concentrations in the presence of trichostatin A (TSA) (250 nM). (D) Quantitation of protein acetylation in panel C as calculated by densitometry of Ac-lysine/total protein. (E) Western blot analysis of SIRT1 and SIRT3 protein levels in 293AD CaSR cells at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h after treatment with high CaCl2 (final concentration of 1.4 mM). Cells were incubated for 0.5 h in low CaCl2 (0.4 mM) before the CaCl2 concentration was increased. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (F) Western blot analysis of SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT6 protein levels in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) at 0.5, 1, and 2 h after histamine treatment, using GAPDH as a loading control. (G) Quantitation of protein levels in panel F as calculated by densitometry relative to GAPDH levels. (H) Relative expression of SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT6 mRNA in HPAECs treated with histamine at 0.5, 1, and 2 h. 18S mRNA was used for normalization. (I and J) Western blot analysis of acetylated histone H3 protein levels in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) (I) and 293AD CaSR cells treated with 1.4 mM CaCl2 in the presence of TSA (250 nM) (J). GAPDH and histone H3 were used as loading controls. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated to the right of the blots. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Lysine acetylation is broadly associated with cellular metabolism, and increased acetylation is commonly observed in metabolic diseases such as diabetes and cancer (41). Thus, it is likely that long-term histamine-triggered accumulation of NADH (Fig. 3A) would initiate a compensatory response to restore cytosolic and mitochondrial protein acetylation and cellular metabolic homeostasis. We therefore measured nucleocytosolic SIRT1 and mitochondrial SIRT3 expression at different time points following the initiation of Ca2+ oscillations in both 293AD CaSR cells and HPAECs. At the 30-min time point that corresponded to increased protein acetylation, we detected no alteration in the expression of SIRT1, which is consistent with diminished enzymatic activity. However, as oscillations persisted, we discovered a gradual increase in SIRT1 protein expression (in 293AD CaSR cells [Fig. 5E] and HPAECs [Fig. 5F and G]). SIRT3 exhibited a variable expression pattern that fluctuated over time. Both SIRT1 and SIRT3 mRNA levels corresponded to increased protein expression in HPAECs (Fig. 5G and H). Along with SIRT1 and SIRT3, HPAECs exhibited an overall increase in the expression of nuclear SIRT6, as well mitochondrion-localized SIRT4 and SIRT5. Cytosolic SIRT2 expression was unaltered by histamine (Fig. 5F and G). Aside from SIRT1 and SIRT3, only elevated SIRT4 and SIRT6 expression was a result of increased transcription, suggesting a complex regulatory process (Fig. 5H). Histone H3 is one of the five core histones and a nuclear target of nucleocytosolic SIRT1 (42), SIRT2 (43), and SIRT6 (44). Concurrent with sirtuin expression, changes in histone H3 acetylation (Ac-H3) were also noted (in HPAECs [Fig. 5I] and in 293AD CaSR cells [Fig. 5J]): Ac-H3 increased at early time points after induction of Ca2+ oscillations and decreased when SIRT1 and SIRT6 expression were at the highest levels.

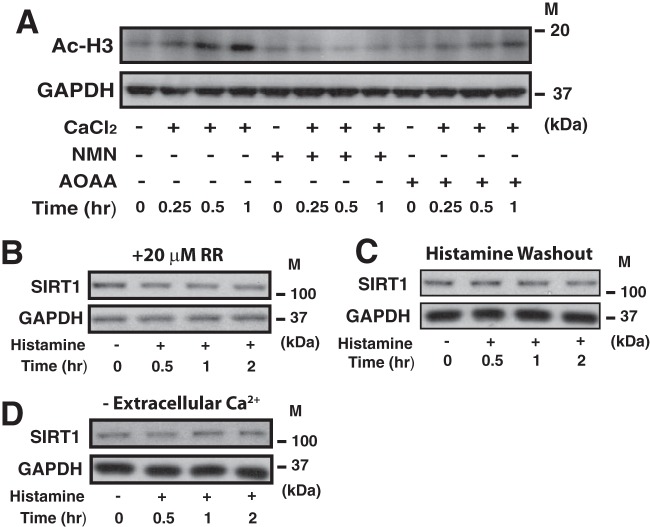

To establish a causal relationship between protein acetylation and sirtuin activity, the [NAD+/NADH]cyt was restored using the cell-permeable NAD+ precursor β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) (45) and Ac-H3 evaluated at the early time point after CaCl2 challenge in 293AD CaSR cells. NMN completely prevented histone H3 hyperacetylation at high CaCl2 concentrations (Fig. 6A). While not as effective as NMN, inhibition of the malate-aspartate shuttle (AOAA) also reduced histone H3 acetylation at early time points of CaCl2 stimulation. Since SIRT1 is the most well-understood member of the sirtuin family in the vascular endothelium, we next measured how manipulating mitochondrial and cytosolic Ca2+ loading influences SIRT1 expression. In HPAECs, diminishing mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake with Ruthenium Red completely abolished the histamine-mediated increase in SIRT1 expression at 2 h (Fig. 6B). Further, eliminating Ca2+ oscillations by either washing out histamine after the initial transient (Fig. 6C) or by removing extracellular Ca2+ uptake also blocked the increase in SIRT1 (Fig. 6D). In total, our data demonstrates that mitochondrial Ca2+ loading can acutely influence protein acetylation by modulating both the activity and expression of sirtuins not only in mitochondria but also in the cytosolic and nuclear compartments.

FIG 6.

Protein acetylation and SIRT1 expression are dependent upon sustained Ca2+ oscillations and mitochondrial Ca2+ loading. (A) Western blot analysis of histone H3 acetylation in 293AD CaSR cells kept at low CaCl2 (0.4 mM) in the presence of TSA (250 nM) at different time points after extracellular CaCl2 was increased to 1.4 mM in the presence of NMN (200 μM) or AOAA (2 mM). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of SIRT1 protein levels in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) in the presence of Ruthenium Red (20 μM) at 0.5, 1, and 2 h after histamine treatment, using GAPDH as a loading control. (C and D) Western blot analysis of SIRT1 protein levels in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) in which Ca2+ oscillations ceased due to histamine washout (C) and removal of extracellular Ca2+ (D). GAPDH was used as a loading control. M, molecular mass.

Mitochondrion-directed SIRT1 upregulation is anti-inflammatory in HPAECs.

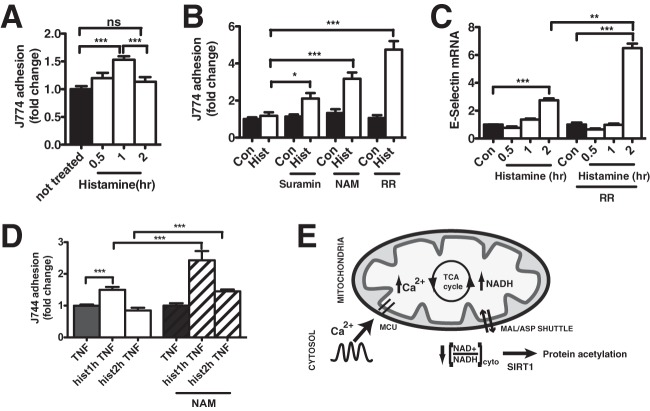

In the vascular endothelium, SIRT1 is an important contributor to angiogenesis, vascular tone, and inflammation (46, 47). During inflammation, activated endothelial cells upregulate the expression of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecules [ICAMs], vascular cell adhesion molecules [VCAMs], and selectins) that facilitate the arrest and recruitment of circulating leukocytes (48–50). To evaluate whether mitochondrion-dependent SIRT1 expression influences endothelial/leukocyte adhesion, J774 macrophages were incubated with HPAECs after histamine challenge. As expected, histamine stimulated an acute increase in J774 macrophage adherence (0.5 and 1 h). Conversely, J774 adhesion was significantly diminished 2 h after histamine challenge (Fig. 7A), coincident with the demonstrated increase in SIRT1 expression by mitochondrion-to-cytosol NADH transmission. To mechanistically link SIRT1 to macrophage adherence, HPAECs were pretreated with the SIRT1 enzymatic inhibitors nicotinamide and suramin (51, 52) and then incubated with J774 macrophages at the 2-h time point. Both suramin and nicotinamide significantly increased J774 adhesion to histamine-treated HPAECs relative to controls (Fig. 7B), demonstrating that sirtuin inhibition increases leukocyte adhesion. Pretreatment of HPAECs with Ruthenium Red, which removed the ability of the mitochondria to upregulate SIRT1 expression, had an even more pronounced effect on J774 adhesion (Fig. 7B) and suggests that mitochondrial Ca2+ import is the key step required to prevent chronic inflammation and leukocyte recruitment. In support, Ruthenium Red treatment significantly increased the mRNA levels of E-selectin 2 h after histamine treatment (Fig. 7C). To evaluate whether the SIRT1-mediated inhibition of leukocyte adhesion was exclusive to histamine, additional studies were conducted by adding the inflammatory agent tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) to HPAECs at 0.5, 1, and 2 h after histamine challenge. Short-term histamine pretreatment (1 h) enhanced TNF-α-mediated leukocyte adhesion over TNF-α alone (Fig. 7D). Conversely, TNF-α-stimulated adhesion was diminished following histamine pretreatment for 2 h, the time point at which SIRT1 was elevated. Inhibition of SIRT1 activity by nicotinamide significantly increased J774 adhesion at both time points, indicating that increased SIRT1 expression is anti-inflammatory in HPAECs. In total, these findings suggest that Ca2+-stimulated mitochondrial bioenergetics are a critical modulator of intracellular signaling cascades via SIRT1 in general and may play a prominent role in vascular inflammation specifically.

FIG 7.

Mitochondrion-directed SIRT1 upregulation is anti-inflammatory in HPAECs. (A) J774 macrophage adhesion to HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) at 0.5, 1, and 2 h after histamine treatment. J774 macrophages were stained with Cell Tracker Green, and the fluorescence of macrophages adherent to HPAECs was measured with a fluorescence plate reader. ns, not significant. (B) J774 macrophage adhesion to HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) for 2 h in the presence of the sirtuin enzymatic inhibitors suramin (50 μM) and nicotinamide (NAM) (10 mM) and in the presence of the mitochondrial uniporter blocker Ruthenium Red (20 μM). (C) Relative mRNA levels of E-selectin in HPAECs treated with histamine (100 nM) in the presence or absence of Ruthenium Red (20 μM) at 0.5, 1, and 2 h after histamine treatment. 18S mRNA was used for normalization. (D) J774 macrophage adhesion to HPAECs treated with TNF (40 ng/ml, 2 h) and histamine (hist) (100 nM) for 1 or 2 h in the presence or absence of nicotinamide (10 mM). Values are means from 3 independent experiments plus SEMs. (E) Schematic representation of results. Ca2+ oscillations effectively raise Ca2+ levels within the mitochondrial matrix, resulting in NADH production by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. NADH not used for energy production will activate the malate-aspartate (MAL-ASP) shuttle to transmit excess reducing equivalents to the cytosol, resulting in a diminished cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio ([NAD+/NADH]cyto). A lowered [NAD+/NADH]cyto influences cytosolic/nuclear sirtuin activity and increases protein acetylation. To compensate for this increase in protein acetylation, a mitochondrial Ca2+-directed increase in SIRT1 expression occurs, which in the endothelium reduces inflammation over time. MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Aside from their obvious importance in energy production, mitochondria have emerged as signaling organelles that integrate and coordinate metabolic responses. While the nuclear control of mitochondrial function (anterograde signaling) is well established (53), the mitochondrial modulation of nuclear gene expression (retrograde response) is largely unknown. Examples of mitochondrial retrograde signaling include the mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitochondrial release of oxidants, nitric oxide, and Ca2+ (54). Our data introduce an additional mode of retrograde signaling, in which mitochondria integrate and translate cytosolic Ca2+ transients into a genetic response via the transmission of mitochondrial NADH to the cytosol and nucleus. We demonstrate the biological significance of Ca2+-mediated mitochondrial retrograde signaling by using primary ECs and provide evidence that the mitochondrial regulation of [NAD+/NADH]cyt can influence the inflammatory responses of these cells.

Cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations are universal signals that affect diverse cellular processes (55) and are rapidly buffered by mitochondria. While the cytosolic consequences of Ca2+ oscillations have been extensively studied, how repetitive Ca2+ waves affect mitochondrial function is still unclear, as mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is largely cell type and agonist dependent. For example, in pancreatic islets and HeLa cells, repetitive [Ca2+]i oscillations desensitize the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and reduce long-term matrix Ca2+ levels (56, 57). Conversely, vasopressin-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in hepatocytes rapidly transmit to the mitochondrial matrix and result in parallel [Ca2+]m oscillations (7). In RBL-2H3 mast cells, adenosine receptor activation (carboxamidoadenosine) effectively increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter activity to elicit a stepwise increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ with each successive transient (58). In our studies, endothelial mitochondrial Ca2+ loading was more efficient during the first cytosolic Ca2+ transient that is released from the intracellular stores. However, while mean mitochondrial Ca2+ loading never reached the magnitude of the original transient, we observed repetitive mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in response to histamine that effectively resulted in an overall mean rise in matrix Ca2+ concentration above the baseline, triggering a chronic activation of matrix dehydrogenases and NADH production. In highly metabolic cardiomyocytes, the Ca2+-stimulated increase in mitochondrial NADH is rapidly consumed to enhance ATP production and provide the energy necessary for cardiac contraction (59, 60). Conversely, our experiments revealed a persistent buildup of mitochondrial NADH in HPAECs in response to cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations that was the result of enhanced NADH production without a requisite increase in ATP synthesis. Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial NADH accumulation has been documented in numerous cell types, including neurons during membrane depolarization (30), hormone-stimulated hepatocytes (7, 61), and pancreatic islets of Langerhans during glucose-induced insulin release (8). In concert with the present findings, we surmise that cytosolic oscillations are likely an efficient means to effect an overall increase in [Ca2+]m, and in turn, initiate a persistent elevation in NADH production within the mitochondrial matrix.

A major consequence of mitochondrial NADH accumulation in HPAECs was the transmission of mitochondrial NADH changes to the cytosolic and nuclear compartments. An estimation of the [NAD+/NADH]cyt revealed a diminished ratio that corresponded to increased mitochondrial NADH production during [Ca2+]i oscillations. With the inner mitochondrial membrane impermeable to NAD+ and NADH, the cytosolic and mitochondrial pools of pyridine nucleotides are well separated and present as distinct free NAD+/NADH ratios (62). However, while there is likely no direct export of NADH out of mitochondria, reducing equivalents can be transported from the matrix to the cytosol via the malate-aspartate (reversible) and glycerol phosphate (irreversible) shuttles (63). In our studies, we detected both a normalization of the NAD+/NADH ratio when Ca2+ oscillations ceased in AD293 CaSR cells and an elevated NAD+/NADH ratio in cells pretreated with AOAA, indicating that the reversible malate-aspartate shuttle is likely the prominent mechanism through which Ca2+-induced mitochondrial bioenergetics are relayed to the cytosol. To compensate, the irreversible glycerol phosphate shuttle could reoxidize NADH to NAD+ in the cytosol (64) and restore the [NAD+/NADH]cyt over time. However, optimal glycerol phosphate activity requires equimolar concentrations of both the cytosolic and mitochondrial components of the cycle (65), which appears to occur only in highly metabolic tissue (66). Indeed, we observed a steady reduction in the [NAD+/NADH]cyt for up to 8 h after histamine stimulation for as long as Ca2+ oscillations were present (data not shown), suggesting that metabolically quiescent ECs may have little glycerol phosphate shuttle activity. In support, the glycerol phosphate shuttle was unable to restore the [NAD+/NADH]cyt in porcine aortic tissue in which malate-aspartate activity was inhibited by AOAA (35), indicating lowered glycerol phosphate shuttle activity in vascular cells. Further study is required to define the relative contributions of both the malate-aspartate and glycerol phosphate shuttle in the transmission of mitochondrial NADH to the cytosol. Interestingly, recent work has identified the malate-aspartate and glycerol phosphate NADH shuttles as regulators of life span in calorie-restricted Saccharomyces cerevisiae via Sir2 (67). In this study, the authors propose that a chronic increase in mitochondrial respiration triggers a rise in the NAD+/NADH ratio, which then transmits to the cytosol through redox shuttles to activate Sir2 (the yeast homolog of SIRT1). Our data demonstrate that mitochondrial redox shuttles not only sense chronic alterations in nutrient availability but that they also allow mitochondria to integrate and convert receptor-mediated Ca2+ transients into an acute cytosolic metabolic signal.

In our studies, the biological effect of mitochondrion-to-cytosol NADH shuttling coincided with alterations in protein acetylation in both the mitochondrial and cytosolic-nuclear compartments. Sirtuins are highly conserved proteins that utilize NAD+ as a cofactor and are therefore exquisitely responsive to changes in the NAD+/NADH ratio (38, 68). Concordant with the notion that NAD+ and NADH are immobile within cells, sirtuins have multiple isoforms localized to different cellular compartments and respond to discrete alterations in their particular microenvironment (SIRT1 and SIRT2 are nucleocytosolic, SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are mitochondrial, SIRT6 and SIRT7 are nuclear) (37). We originally surmised that Ca2+-mediated NADH accumulation would predominately affect proteins within the mitochondria (i.e., MnSOD). However, we were surprised at the extent to which alterations in PTEN and p53 acetylation occurred in the cytosolic compartment. Reversible protein acetylation is an evolutionarily conserved posttranslational regulatory mechanism that alters the activity of metabolic enzymes involved in glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, urea cycle, and fatty acid metabolism (69). Thus, the ability of the mitochondria to influence cytosolic metabolic proteins via acetylation represents a convenient mechanism by which mitochondria can coordinate metabolism between adjoining cellular compartments. In addition to cytosolic proteins, we also detected mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent alterations in the acetylation of nuclear histone H3. Changes in histone acetylation concomitant with the mitochondrial NADH homeostasis suggest the possibility that mitochondrial metabolism influences not only cytosolic and mitochondrial processes but may also initiate cellular metabolic reprogramming through epigenetic mechanisms.

The transcriptional regulation of sirtuin expression is complex and has been studied predominantly during dietary modifications by nutrient starvation (caloric restriction) or nutrient excess (high-fat diet) (37). Several pathways have been proposed to explain SIRT1 upregulation upon nutrient withdrawal, including Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a)-p53 (70), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) (71), cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) (72), and PPARδ (73). Our studies demonstrate an inverse relationship between protein acetylation and sirtuin expression. The rapid cellular dynamics of this interaction suggests a compensatory mechanism in which expression of nucleocytosolic and mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT1 and SIRT3) rises to counter a reduction in enzyme activity. An interesting potential link between changes in NADH levels and variations in SIRT1 expression is the SIRT1 transcriptional regulation by the NADH-sensitive transcriptional corepressor C-terminus-binding protein (CtBP) (74). However, this study noted an inverse relationship between free NADH levels and SIRT1 transcription. While we did not investigate the exact transcriptional machinery engaged by mitochondrial NADH shuttling, we demonstrate using two different cell types that increased SIRT1 expression occurs during physiologic Ca2+ signaling and SIRT1 upregulation is linked to a mitochondrion-directed decrease in the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio.

Endothelial SIRT1 targets multiple proteins to effectively modulate nitric oxide production (75, 76), inflammation (47, 77, 78), and vessel growth (79, 80). Thus, SIRT1 expression is widely considered a positive effector of EC function. Indeed, our study demonstrates that mitochondrial upregulation of SIRT1 expression has an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing the expression of adhesion molecules (E-selectin) and preventing the recruitment of circulating leukocytes. At the molecular level, the inhibitory effect of increased SIRT1 on adhesion molecule expression may be mediated by the NF-κB pathway. Indeed, SIRT1 inhibits NF-κB transcription by directly interacting and deacetylating RelA/p65 (81). The vasoprotective effect SIRT1 as well as its inhibitory effect on the expression of adhesion molecules has been previously documented. In TNF-α-stimulated endothelial cells, endogenous SIRT1 levels prevented superoxide production and expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by suppressing NF-κB signaling (82). Similarly, resveratrol-induced SIRT1 expression directed the expression of vasoprotective transcription factor Kruppel-like factor KLF2 (83) and protected endothelial cells against the effects of cigarette smoking-induced oxidative stress by invoking antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic mechanisms (84).

In summary, our studies demonstrate that enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ loading results in a persistent elevation of NADH within the matrix. When not used as a substrate for ATP generation, NADH transmits to the cytosol to influence protein acetylation and gene expression. The biological significance of this finding was demonstrated using primary human ECs, in which mitochondrial Ca2+-driven bioenergetics participates as a negative regulator of inflammation and leukocyte adhesion. Taken together, our results reveal a fundamental mechanism by which mitochondria regulate cytosolic NAD+/NADH metabolism to initiate retrograde signaling, epigenetic regulation, and metabolic adaptation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Hockenbery and Daciana Margineantu for their assistance in the Seahorse assay measurements and Seahorse Bioscience for providing reagents and technical instruction. We also thank Gerda Breitwieser for the CaSR plasmid and technical advice.

This study was supported by HL094536 and a UW RRF award to B.J.H.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas AP, Bird GS, Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Putney JW., Jr 1996. Spatial and temporal aspects of cellular calcium signaling. FASEB J. 10:1505–1517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton RM, McCormack JG. 1986. The calcium sensitive dehydrogenases of vertebrate mitochondria. Cell Calcium 7:377–386. 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90040-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson SM, Duchen MR. 2007. Endothelial mitochondria: contributing to vascular function and disease. Circ. Res. 100:1128–1141. 10.1161/01.RES.0000261970.18328.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarasov AI, Griffiths EJ, Rutter GA. 2012. Regulation of ATP production by mitochondrial Ca(2+). Cell Calcium 52:28–35. 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glancy B, Balaban RS. 2012. Role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of cellular energetics. Biochemistry 51:2959–2973. 10.1021/bi2018909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jouaville LS, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, Rutter GA, Rizzuto R. 1999. Regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by calcium: evidence for a long-term metabolic priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13807–13812. 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajnoczky G, Robb-Gaspers LD, Seitz MB, Thomas AP. 1995. Decoding of cytosolic calcium oscillations in the mitochondria. Cell 82:415–424. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90430-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luciani DS, Misler S, Polonsky KS. 2006. Ca2+ controls slow NAD(P)H oscillations in glucose-stimulated mouse pancreatic islets. J. Physiol. 572:379–392. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Territo PR, French SA, Balaban RS. 2001. Simulation of cardiac work transitions, in vitro: effects of simultaneous Ca2+ and ATPase additions on isolated porcine heart mitochondria. Cell Calcium 30:19–27. 10.1054/ceca.2001.0211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borregaard N, Herlin T. 1982. Energy metabolism of human neutrophils during phagocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 70:550–557. 10.1172/JCI110647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culic O, Gruwel ML, Schrader J. 1997. Energy turnover of vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 273:C205–C213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins BJ, Solt LA, Chowdhury I, Kazi AS, Abid MR, Aird WC, May MJ, Foskett JK, Madesh M. 2007. G protein-coupled receptor Ca2+-linked mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are essential for endothelial/leukocyte adherence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:7582–7593. 10.1128/MCB.00493-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bock M, Wang N, Decrock E, Bol M, Gadicherla AK, Culot M, Cecchelli R, Bultynck G, Leybaert L. 2013. Endothelial calcium dynamics, connexin channels and blood-brain barrier function. Prog. Neurobiol. 108:1–20. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandhirajan RK, Meng S, Chandramoorthy HC, Mallilankaraman K, Mancarella S, Gao H, Razmpour R, Yang XF, Houser SR, Chen J, Koch WJ, Wang H, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Madesh M. 2013. Blockade of NOX2 and STIM1 signaling limits lipopolysaccharide-induced vascular inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 123:887–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Quadri S, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. 2003. Mechano-oxidative coupling by mitochondria induces proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J. Clin. Invest. 111:691–699. 10.1172/JCI17271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Q, Deshpande S, Irani K, Ziegelstein RC. 1999. [Ca(2+)](i) oscillation frequency regulates agonist-stimulated NF-kappaB transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33995–33998. 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu L, Luo Y, Chen T, Chen F, Wang T, Hu Q. 2008. Ca2+ oscillation frequency regulates agonist-stimulated gene expression in vascular endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 121:2511–2518. 10.1242/jcs.031997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu L, Song S, Pi Y, Yu Y, She W, Ye H, Su Y, Hu Q. 2011. Cumulated Ca2(+) spike duration underlies Ca2(+) oscillation frequency-regulated NFkappaB transcriptional activity. J. Cell Sci. 124:2591–2601. 10.1242/jcs.082727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhlen P. 2004. Spectral analysis of calcium oscillations. Sci. STKE 2004:pl15. 10.1126/stke.2582004pl15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer AE, Tsien RY. 2006. Measuring calcium signaling using genetically targetable fluorescent indicators. Nat. Protoc. 1:1057–1065. 10.1038/nprot.2006.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCombs JE, Palmer AE. 2008. Measuring calcium dynamics in living cells with genetically encodable calcium indicators. Methods 46:152–159. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung YP, Albeck JG, Tantama M, Yellen G. 2011. Imaging cytosolic NADH-NAD(+) redox state with a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Cell Metab. 14:545–554. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung YP, Yellen G. 2014. Live-cell imaging of cytosolic NADH-NAD+ redox state using a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Methods Mol. Biol. 1071:83–95. 10.1007/978-1-62703-622-1_7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. 1967. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem. J. 103:514–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. 2000. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:11–21. 10.1038/35036035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antigny F, Girardin N, Frieden M. 2012. Transient receptor potential canonical channels are required for in vitro endothelial tube formation. J. Biol. Chem. 287:5917–5927. 10.1074/jbc.M111.295733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pober JS, Sessa WC. 2007. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7:803–815. 10.1038/nri2171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Mammucari C. 2012. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:566–578. 10.1038/nrm3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCormack JG, Denton RM. 1993. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and the role of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of energy metabolism. Dev. Neurosci. 15:165–173. 10.1159/000111332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duchen MR. 1992. Ca(2+)-dependent changes in the mitochondrial energetics in single dissociated mouse sensory neurons. Biochem. J. 283(Part 1):41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintero M, Colombo SL, Godfrey A, Moncada S. 2006. Mitochondria as signaling organelles in the vascular endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5379–5384. 10.1073/pnas.0601026103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin SJ, Guarente L. 2003. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, a metabolic regulator of transcription, longevity and disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:241–246. 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00006-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Lisa F, Ziegler M. 2001. Pathophysiological relevance of mitochondria in NAD(+) metabolism. FEBS Lett. 492:4–8. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02198-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J. 2010. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 31:194–223. 10.1210/er.2009-0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barron JT, Gu L, Parrillo JE. 1998. Malate-aspartate shuttle, cytoplasmic NADH redox potential, and energetics in vascular smooth muscle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 30:1571–1579. 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breitwieser GE. 2012The intimate link between calcium sensing receptor trafficking and signaling: implications for disorders of calcium homeostasis. Mol. Endocrinol. 26:1482–1495. 10.1210/me.2011-1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. 2012. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:225–238. 10.1038/nrm3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin SJ, Ford E, Haigis M, Liszt G, Guarente L. 2004. Calorie restriction extends yeast life span by lowering the level of NADH. Genes Dev. 18:12–16. 10.1101/gad.1164804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Revollo JR, Grimm AA, Imai S. 2004. The NAD biosynthesis pathway mediated by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates Sir2 activity in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:50754–50763. 10.1074/jbc.M408388200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Kazgan N. 2011. Mammalian sirtuins and energy metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7:575–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iyer A, Fairlie DP, Brown L. 2012. Lysine acetylation in obesity, diabetes and metabolic disease. Immunol. Cell Biol. 90:39–46. 10.1038/icb.2011.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan J, Pu M, Zhang Z, Lou Z. 2009. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is important for genomic stability in mammals. Cell Cycle 8:1747–1753. 10.4161/cc.8.11.8620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eskandarian HA, Impens F, Nahori MA, Soubigou G, Coppee JY, Cossart P, Hamon MA. 2013. A role for SIRT2-dependent histone H3K18 deacetylation in bacterial infection. Science 341:1238858. 10.1126/science.1238858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwer B, Schumacher B, Lombard DB, Xiao C, Kurtev MV, Gao J, Schneider JI, Chai H, Bronson RT, Tsai LH, Deng CX, Alt FW. 2010. Neural sirtuin 6 (Sirt6) ablation attenuates somatic growth and causes obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:21790–21794. 10.1073/pnas.1016306107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshino J, Mills KF, Yoon MJ, Imai S. 2011. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD(+) intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 14:528–536. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potente M, Dimmeler S. 2008. Emerging roles of SIRT1 in vascular endothelial homeostasis. Cell Cycle 7:2117–2122. 10.4161/cc.7.14.6267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein S, Matter CM. 2011. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle 10:640–647. 10.4161/cc.10.4.14863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cid MC, Kleinman HK, Grant DS, Schnaper HW, Fauci AS, Hoffman GS. 1994. Estradiol enhances leukocyte binding to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated endothelial cells via an increase in TNF-induced adhesion molecules E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule type 1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule type 1. J. Clin. Invest. 93:17–25. 10.1172/JCI116941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munro JM, Pober JS, Cotran RS. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma induce distinct patterns of endothelial activation and associated leukocyte accumulation in skin of Papio anubis. Am. J. Pathol. 135:121–133 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborn L, Hession C, Tizard R, Vassallo C, Luhowskyj S, Chi-Rosso G, Lobb R. 1989. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell 59:1203–1211. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. 2002. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45099–45107. 10.1074/jbc.M205670200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trapp J, Meier R, Hongwiset D, Kassack MU, Sippl W, Jung M. 2007. Structure-activity studies on suramin analogues as inhibitors of NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases (sirtuins). ChemMedChem 2:1419–1431. 10.1002/cmdc.200700003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finley LW, Haigis MC. 2009. The coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial communication during aging and calorie restriction. Ageing Res. Rev. 8:173–188. 10.1016/j.arr.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butow RA, Avadhani NG. 2004. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol. Cell 14:1–15. 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00179-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smedler E, Uhlen P. 2014. Frequency decoding of calcium oscillations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840:964–969. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collins TJ, Lipp P, Berridge MJ, Bootman MD. 2001. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake depends on the spatial and temporal profile of cytosolic Ca(2+) signals. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26411–26420. 10.1074/jbc.M101101200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maechler P, Kennedy ED, Wang H, Wollheim CB. 1998. Desensitization of mitochondrial Ca2+ and insulin secretion responses in the beta cell. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20770–20778. 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csordas G, Hajnoczky G. 2003. Plasticity of mitochondrial calcium signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:42273–42282. 10.1074/jbc.M305248200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell CJ, Bright NA, Rutter GA, Griffiths EJ. 2006. ATP regulation in adult rat cardiomyocytes: time-resolved decoding of rapid mitochondrial calcium spiking imaged with targeted photoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28058–28067. 10.1074/jbc.M604540200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heineman FW, Balaban RS. 1993. Effects of afterload and heart rate on NAD(P)H redox state in the isolated rabbit heart. Am. J. Physiol. 264:H433–H440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robb-Gaspers LD, Burnett P, Rutter GA, Denton RM, Rizzuto R, Thomas AP. 1998. Integrating cytosolic calcium signals into mitochondrial metabolic responses. EMBO J. 17:4987–5000. 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ying W. 2008. NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 10:179–206. 10.1089/ars.2007.1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McKenna MC, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, Sonnewald U. 2006. Neuronal and astrocytic shuttle mechanisms for cytosolic-mitochondrial transfer of reducing equivalents: current evidence and pharmacological tools. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71:399–407. 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mracek T, Drahota Z, Houstek J. 2013. The function and the role of the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827:401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohkawa KI, Vogt MT, Farber E. 1969. Unusually high mitochondrial alpha glycerophosphate dehydrogenase activity in rat brown adipose tissue. J. Cell Biol. 41:441–449. 10.1083/jcb.41.2.441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sacktor B, Cochran DG. 1958. The respiratory metabolism of insect flight muscle. I. Manometric studies of oxidation and concomitant phosphorylation with sarcosomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 74:266–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Easlon E, Tsang F, Skinner C, Wang C, Lin SJ. 2008. The malate-aspartate NADH shuttle components are novel metabolic longevity regulators required for calorie restriction-mediated life span extension in yeast. Genes Dev. 22:931–944. 10.1101/gad.1648308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmidt MT, Smith BC, Jackson MD, Denu JM. 2004. Coenzyme specificity of Sir2 protein deacetylases: implications for physiological regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 279:40122–40129. 10.1074/jbc.M407484200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T, Yao J, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Li H, Li Y, Shi J, An W, Hancock SM, He F, Qin L, Chin J, Yang P, Chen X, Lei Q, Xiong Y, Guan KL. 2010. Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science 327:1000–1004. 10.1126/science.1179689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. 2004. Nutrient availability regulates SIRT1 through a forkhead-dependent pathway. Science 306:2105–2108. 10.1126/science.1101731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hayashida S, Arimoto A, Kuramoto Y, Kozako T, Honda S, Shimeno H, Soeda S. 2010. Fasting promotes the expression of SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase, via activation of PPARalpha in mice. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 339:285–292. 10.1007/s11010-010-0391-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noriega LG, Feige JN, Canto C, Yamamoto H, Yu J, Herman MA, Mataki C, Kahn BB, Auwerx J. 2011. CREB and ChREBP oppositely regulate SIRT1 expression in response to energy availability. EMBO Rep. 12:1069–1076. 10.1038/embor.2011.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Okazaki M, Iwasaki Y, Nishiyama M, Taguchi T, Tsugita M, Nakayama S, Kambayashi M, Hashimoto K, Terada Y. 2010. PPARbeta/delta regulates the human SIRT1 gene transcription via Sp1. Endocr. J. 57:403–413. 10.1507/endocrj.K10E-004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang Q, Wang SY, Fleuriel C, Leprince D, Rocheleau JV, Piston DW, Goodman RH. 2007. Metabolic regulation of SIRT1 transcription via a HIC1:CtBP corepressor complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:829–833. 10.1073/pnas.0610590104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 75.Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Falcone S, Valerio A, Cantoni O, Clementi E, Moncada S, Carruba MO. 2005. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science 310:314–317. 10.1126/science.1117728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ota H, Eto M, Kano MR, Kahyo T, Setou M, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Akishita M, Ouchi Y. 2010. Induction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, SIRT1, and catalase by statins inhibits endothelial senescence through the Akt pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30:2205–2211. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stein S, Schafer N, Breitenstein A, Besler C, Winnik S, Lohmann C, Heinrich K, Brokopp CE, Handschin C, Landmesser U, Tanner FC, Luscher TF, Matter CM. 2010. SIRT1 reduces endothelial activation without affecting vascular function in ApoE−/− mice. Aging (Albany, NY) 2:353–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Breitenstein A, Stein S, Holy EW, Camici GG, Lohmann C, Akhmedov A, Spescha R, Elliott PJ, Westphal CH, Matter CM, Luscher TF, Tanner FC. 2011. Sirt1 inhibition promotes in vivo arterial thrombosis and tissue factor expression in stimulated cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 89:464–472. 10.1093/cvr/cvq339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheng BB, Yan ZQ, Yao QP, Shen BR, Wang JY, Gao LZ, Li YQ, Yuan HT, Qi YX, Jiang ZL. 2012. Association of SIRT1 expression with shear stress induced endothelial progenitor cell differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 113:3663–3671. 10.1002/jcb.24239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sundaresan NR, Pillai VB, Wolfgeher D, Samant S, Vasudevan P, Parekh V, Raghuraman H, Cunningham JM, Gupta M, Gupta MP. 2011. The deacetylase SIRT1 promotes membrane localization and activation of Akt and PDK1 during tumorigenesis and cardiac hypertrophy. Sci. Signal. 4:ra46. 10.1126/scisignal.2001465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. 2004. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 23:2369–2380. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stein S, Schafer N, Breitenstein A, Besler C, Winnik S, Lohmann C, Heinrich K, Brokopp CE, Handschin C, Landmesser U, Tanner FC, Luscher TF, Matter CM. 2010. SIRT1 reduces endothelial activation without affecting vascular function in ApoE−/− mice. Aging 2:353–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gracia-Sancho J, Villarreal G, Jr, Zhang Y, Garcia-Cardena G. 2010. Activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol induces KLF2 expression conferring an endothelial vasoprotective phenotype. Cardiovasc. Res. 85:514–519. 10.1093/cvr/cvp337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Podlutsky A, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Zhang C, Mukhopadhyay P, Pacher P, Hu F, de Cabo R, Ballabh P, Ungvari Z. 2008. Vasoprotective effects of resveratrol and SIRT1: attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory phenotypic alterations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 294:H2721–H2735. 10.1152/ajpheart.00235.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]