Abstract

The RING domain protein Arkadia/RNF111 is a ubiquitin ligase in the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) pathway. We previously identified Arkadia as a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-binding protein with clustered SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) that together form a SUMO-binding domain (SBD). However, precisely how SUMO interaction contributes to the function of Arkadia was not resolved. Through analytical molecular and cell biology, we found that the SIMs share redundant function with Arkadia's M domain, a region distinguishing Arkadia from its paralogs ARKL1/ARKL2 and the prototypical SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) RNF4. The SIMs and M domain together promote both Arkadia's colocalization with CBX4/Pc2, a component of Polycomb bodies, and the activation of a TGFβ pathway transcription reporter. Transcriptome profiling through RNA sequencing showed that Arkadia can both promote and inhibit gene expression, indicating that Arkadia's activity in transcriptional control may depend on the epigenetic context, defined by Polycomb repressive complexes and DNA methylation.

INTRODUCTION

Posttranslational modification by the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) family proteins targets a large number of proteins in multiple cellular processes, such as transcription, DNA replication, and DNA damage repair, in eukaryotes (1–3). As in other forms of posttranslational modification, SUMO is recognized by a specific structure, the SUMO-interacting motif (SIM). Thus, sumoylation promotes a regulated protein complex assembly through a direct interaction between SUMO and SIM (4, 5). Sumoylation activity has been found in microscopically visible nuclear bodies (NBs), such as promyelocytic leukemia (PML) and Polycomb (Pc) bodies (6–9). These nuclear bodies contain sumoylation enzymes, sumoylated proteins, and SIM-containing proteins (10–12), suggesting that both SUMO conjugation and SUMO binding regulate the dynamic formation of nuclear bodies (4, 6).

Recently, we applied a computational string search to SIM identification and found a group of proteins all containing clustered SIMs (13). This includes a RING domain protein called Arkadia, or RNF111, that has a cluster of at least three SIMs in a region between residues 253 and 415 that we now call a SUMO-binding domain (SBD). This work echoed our previous finding of the SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) RNF4 and its fission yeast homologs, Rfp1 and Rfp2, all containing multiple SIMs closely positioned as a cluster (14). Sequence gazing on Arkadia has also led to similar findings by other groups (15, 16). Among the three Arkadia SIMs, SIM3 is the most critical, and its particular sequence (VVDLT) resembles a VIDLT-type high-affinity SIM (17); SIM1 and SIM3 together contribute to the bulk of SUMO affinity of the entire SBD, and their simultaneous mutation results in complete loss of SUMO binding (13).

Arkadia also has a pair of partial paralogs found in all vertebrates, namely, Arkadia-like 1 (ARKL1) and 2 (ARKL2, or RNF165) (18). They resemble the N- and C-terminal half of Arkadia, respectively, and are encoded by genes in adjacent loci in all vertebrate genomes. Notably, prior to our identification of SIMs in Arkadia, ARKL1 itself had been experimentally identified twice as a SUMO-binding protein, through a glutathione S-transferase (GST)–SUMO2 affinity capture (as Arkadia-like) (19) and through a yeast two-hybrid screen against SUMO (as C18orf25 [chromosome 18 open reading frame 25]) (20). Presumably, Arkadia and ARKL1/ARKL2 share an origin—their split is likely the result of a genome duplication event in the rise of vertebrates during animal evolution.

Arkadia has been shown to be a positive regulator of transcriptional activation by transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily cytokines. It was initially named after the arkadia mutation in mice: the homozygous arkadia mouse fails in early embryonic development due to deficiency in the induction of the node, an indication of missing Nodal signaling (21). Ectopic expression of Arkadia in developing Xenopus laevis embryos also enhanced the signals of certain TGFβ family members, such as activin and Nodal-related 1, which drive the formation of mesendoderm (22). In cultured cells, Arkadia promotes the activation of TGFβ pathway-specific, Smad3/Smad4-targeted gene transcription, and the knockdown of Arkadia by small interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibits such activation (23, 24). A number of early studies suggested that, at the molecular level, Arkadia acts as a ubiquitin ligase and causes the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of the inhibitory factors downstream from TGFβ, such as Smad7, an inhibitory Smad, and transcriptional repressors SnoN and c-Ski, through its RING domain-based E3 activity (23–27). Arkadia may also regulate the turnover of phosphorylated Smad2 or Smad3 (28). Precisely how the structural elements of Arkadia dictate its function in embryonic development, however, is not well understood.

The idea that Arkadia may be a STUbL has led to investigations that draw an analogy between Arkadia and RNF4, suggesting Arkadia may also possess an RNF4-like function in protecting genomic integrity (16) and in promoting the degradation of PML in arsenic trioxide (As2O3)-treated cells (15). However, it remains unclear how the SIMs in Arkadia might contribute to its activity in transcription downstream from TGFβ. We have conducted a detailed structural-functional dissection to distinguish Arkadia from RNF4 and ARKL1/ARKL2. We found that the Arkadia SUMO-binding domain is among the structures in Arkadia that together are essential for both an avidity-driven recruitment to Polycomb bodies and Arkadia's function in the transcriptional regulation of epigenetically silenced genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The cDNA of mouse Arkadia, encoding a 981-residue isoform, was obtained from the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC). Mouse ARKL1 and ARKL2 cDNAs were reverse transcription (RT)-PCR amplified using a total RNA preparation from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). The mutant Arkadia constructs used in this study, including the M domain deletion mutants, RNF4-Arkadia chimera (R4-Ark; with the N-terminal 125 residues of RNF4 and the C-terminal 256 residues of Arkadia), and ARKL1-ARKL2 fusion mutant, were based on the mouse cDNA. The mutants were generated using PCR amplification (Phusion; New England BioLabs) or PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Agilent). Myc-CBX4 was a gift from Jennifer Higginbotham in Clodagh O'Shea's group. The TβR1* expression vector and the CAGA12-adenovirus major late promoter (MLP)-luciferase reporter were gifts from Carl-Henrik Heldin (29). For in vitro methylation, the plasmid DNA was amplified and purified, using Escherichia coli strain SCS110 (Agilent) as the host, and incubated with CpG methylase M.SssI (New England BioLabs) at 25°C overnight (1 μg DNA, 4 units enzyme, 6 nmol S-adenosyl methionine), and the methylated DNA was recovered by isopropanol precipitation. Mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10) from ascites fluid was raised in-house. Antibodies from commercial sources included mouse and rabbit anti-Flag antibodies (F3165 and F7425; Sigma), mouse anti-PML monoclonal antibody (PG-M3) (sc-966; Santa Cruz Biotech), and rabbit anti-Arkadia antibody (H00054778-B01P; Abnova).

Yeast plasmid shuffle.

RNF4, Arkadia, and their mutants were expressed in fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, driven by an nmt1 promoter (30). Plasmid shuffling was carried out as previously described (31).

Retroviral reconstitution of Arkadia expression in Ark−/− MEFs.

Ark−/− MEFs were gift from Vasso Episkopou (21) and were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). Recombinant retroviruses were based on retroviral vector CAG-GFP, expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and derived from murine Moloney leukemia virus (MMLV) (32). The synthetic CAG promoter drives the simultaneous expression of Arkadia and enhanced GFP (EGFP) via an internal ribosomal entry site. Virus was packaged in 293T cells and was concentrated through ultraspeed centrifugation. Ark−/− MEFs were freshly plated in a 60-mm dish for 4 h and infected for 24 h with virus preparations of ∼5 × 104 CFU to a >95% efficiency. Early passages of the infected MEFs were used for experiments to avoid retroviral silencing after cell divisions. Cells growing in the 60-mm dish at ∼40% confluence were treated with TGFβ (PeproTech) at 2.5 ng/ml for 4 h, followed by total RNA extraction with the Nucleospin RNA kit (Clontech). The mouse gene expression level was measured by RT-quantitative PCR (using SuperScript III and Power SYBR green PCR master mix; Life Technologies) and normalized to the expression level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The PCR primer sequences used in the study were as follows: 5′-AACCCGGCGGCAGATC and 5′-TCCACGGCCCCATGAG for PAI-1/Serpine1, 5′-TGGATGGTGACCTCTGGTTG and 5′-GCAGGAAAAATTGGGTTCGTGAG for Cck, and 5′-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG and 5′-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′ for GAPDH.

RNA sequencing.

MEFs grown for 2 days in a 60-mm dish were harvested at ∼40% confluence. Following TGFβ (PeproTech) stimulation at 2.5 ng/ml for 1 and 4 h, total RNA was extracted using a Nucleospin RNA kit (Clontech) with in-column DNase digestion. The RNA quality was verified to have an RNA integrity number (RIN) greater than 7.5 through using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Stranded mRNA-seq (mRNA sequencing) libraries were prepared from poly(A) RNA after oligo(dT) selection. Sequence reads were generated on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system and mapped to an annotated mouse genome (version mm9) by STAR (33). The gene expression level, represented by fragments per kilo base per million reads (FPKM), was calculated using Cufflinks (34). Data cleanup, selection, hierarchical clustering, and heat map illustration were carried out with custom Python scripts.

Transient transfection of 293T cells and immunoprecipitation.

The 293T cells were transfected with an appropriate amount of DNA using polyethylenimine (PEI). Transfections were carried out in 24-well plates, 60-mm dishes, and 100-mm dishes for luciferase assays, coimmunoprecipitation assays, and immunoprecipitation-coupled ubiquitin ligase assays, respectively. Cells were replenished with fresh medium 5 h after transfection. Total cell lysates were prepared 2 days after transfection. For coimmunoprecipitation assays, cells were lysed with 600 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, protease inhibitor cocktail) per 60-mm dish. Immunoprecipitation was carried out by a 2-h incubation with anti-Flag antibody (M2)-conjugated agarose beads (Sigma). The immune complex-bound beads were washed three times with the lysis buffer and analyzed through SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation-coupled ubiquitin ligase assay.

Flag-tagged proteins were each precipitated from 293T cell lysates with 20 μl (bed volume) of anti-Flag antibody–agarose beads. The washed beads were used as the source of E3 in two parallel sets of ubiquitin ligase assays (14, 31). The reaction mixture included either hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin for detection of nonspecific ubiquitin conjugation or a combination of untagged ubiquitin with HA-tagged di-SUMO2-GST fusion protein for the detection of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase activity. The reaction products were resolved with SDS-PAGE and visualized with an anti-HA antibody immunoblot assay.

Luciferase assay.

For luciferase assay, 293T cells were transfected in 24-well plates with a total of 0.5 μg of DNA, which included 5 ng of unmethylated or 50 ng of in vitro methylated CAGA12-MLP-luciferase plasmid. Total cell lysates were prepared 2 days after transfection with 250 μl/well luciferase assay lysis buffer, and luciferase activity was measured by mixing 5 μl of lysate and 100 μl of firefly luciferase substrate (Biotium). All luciferase activities are shown as the fold activation compared to the activity of TβR1* alone. In plotting the luciferase assay results (see Fig. 4 and 8), the data points were slightly scattered along the x axis in order to provide an ensemble view of all data from multiple independent experiments.

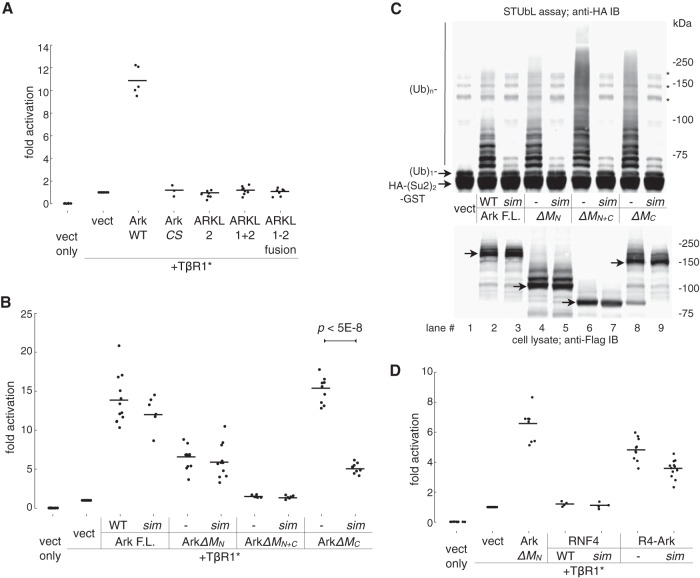

FIG 4.

The M domain of Arkadia is essential for function. (A) The activities of Arkadia and ARKL1/ARKL2 were compared in a reporter assay for the activation of a TGFβ-responsive promoter. Transient transfection of plasmid was carried out as indicated; luciferase assay was performed on 293T cell lysates 2 days after transfection. Luciferase activity is shown as fold activation relative to the activity obtained with TβR1* alone. TβR1*, constitutively active mutant of TGFβ type I receptor (also known as ALK5*, with a T204D mutation in the kinase domain); CS, Arkadia RING domain mutant C966S. All data points from multiple independent experiments are plotted as dots slightly scattered along the x axis, with horizontal lines showing the average values. (B) Activities of Arkadia and its mutants. F.L., full-length Arkadia; sim, Arkadia sim13m mutant. M domain deletion mutants are as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Transfection and luciferase assay were conducted as described for panel A. The significance of difference (P value) between the activities of ArkΔMC and its corresponding sim mutant was estimated based on a paired, one-tailed Student's t test. (C) SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase activity of Arkadia and its mutants. The assay was carried out essentially as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. Various forms of Flag-tagged Arkadia (as indicated) were immunoprecipitated from the lysates of transfected 293T cells and subjected to ubiquitylation assay using free ubiquitin (Ub) and an HA-(SUMO2)2-GST [HA-(Su2)2-GST] fusion protein as substrates. Top, anti-HA antibody immunoblot showing the modification of HA-(SUMO2)2-GST as a result of the in vitro STUbL activity of Arkadia proteins. *, nonspecific bands, likely high-molecular-mass aggregates of HA-(SUMO2)2-GST. Bottom, an anti-Flag antibody immunoblot showing the expression of Arkadia proteins in the cell lysates prior to immunoprecipitation (arrows are pointing at the base forms of Arkadia proteins). (D) Activity of an RNF4-Arkadia fusion protein, R4-Ark, against the TGFβ-responsive promoter. R4-Ark is a fusion of the N-terminal 125 residues of RNF4 (RNF4 1 to 125) and the C-terminal 256 residues of Arkadia (Arkadia 726 to 981). sim, sim23m in the RNF4 SUMO-binding domain. Data points are plotted as described for panels A and B.

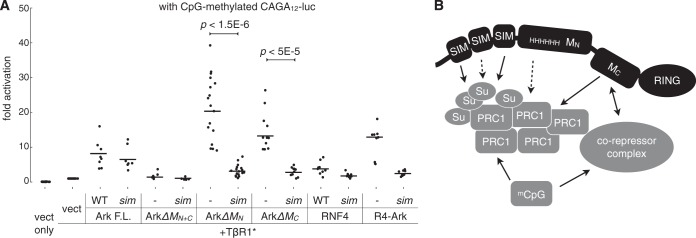

FIG 8.

Arkadia promotes SIM-dependent transcriptional activation of a CpG methylation-silenced promoter specifically for the TGFβ pathway. (A) The CAGA12 luciferase plasmid was methylated in vitro prior to transfection as described in Materials and Methods. Transfection of Arkadia constructs (as indicated) and luciferase assay were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 4. All data points from multiple independent experiments are plotted as dots slightly scattered along the x axis, with their mean values highlighted by horizontal lines. The significance of differences (P value) between the activities of ArkΔMN or ArkΔMC and their corresponding sim mutants was estimated based on a paired, one-tailed Student's t test. (B) A model illustrating the SIM-dependent and SIM-independent mechanisms for the function of Arkadia. Arkadia is shown to participate in protein-protein interaction through multiple structures, providing a means of communication between the SUMO pathway-concentrated Polycomb bodies and corepressor complex. PRC1, Polycomb repressive complex 1; Su, SUMO; mCpG, methylated CpG islands.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

U2OS cells growing on acid-washed glass coverslips were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). To prepare samples for microscopy, transfected cells were rinsed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% formaldehyde (diluted with PBS from a 16% stock) for 20 min, and rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl). Fixed cells were blocked and permeabilized with TBS containing 3% (vol/vol) bovine serum and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 60 min and incubated stepwise with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, Alexa Fluor 488 or 568-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h, and Hoechst 33342 for 15 min, with each staining step followed by extensive washing with TBS. Immunostained cells were sealed in polyvinyl alcohol mounting medium (Thermo Scientific). Fluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 710 or 780 laser-scanning confocal microscope with a 63× objective lens and were saved in 8-bit red-green-blue (RGB) format, comprising fluorescence signals from three separate channels. For a quantitative estimation of protein colocalization, Pearson's correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) between two channels was calculated using the two entire sets of pixel intensity from a cropped image (usually 200 by 200 pixels); matrix representation of images and statistical computing were implemented using the SciPy library.

RESULTS

A direct functional coupling between Arkadia's SUMO-binding and ubiquitin ligase domains is evident in vitro but lacking in vivo.

Prompted by the similarity between Arkadia and RNF4 in their SIMs-RING domain configuration, we compared their in vitro activities in a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) assay. Immunoprecipitated Arkadia and RNF4 proteins from transfected 293T cells were assayed for their ubiquitin ligase activities against an HA–di-SUMO2–GST substrate (Fig. 1A) (31). Arkadia indeed promoted the ubiquitylation of di-SUMO2, in a manner similar to RNF4 although less strongly, and such modification was specifically dependent on both the SUMO-binding and the RING domains of Arkadia (Fig. 1A, top). As a control, when the formation of nonspecific ubiquitin-protein conjugates was examined in a parallel assay, both the wild type (WT) and the sim mutant form of Arkadia showed similar activities. The RING mutant was inactive, as expected, demonstrating that the E3 catalytic activity of Arkadia is solely RING dependent (Fig. 1A, bottom). We conclude that, in vitro, Arkadia can act as a STUbL.

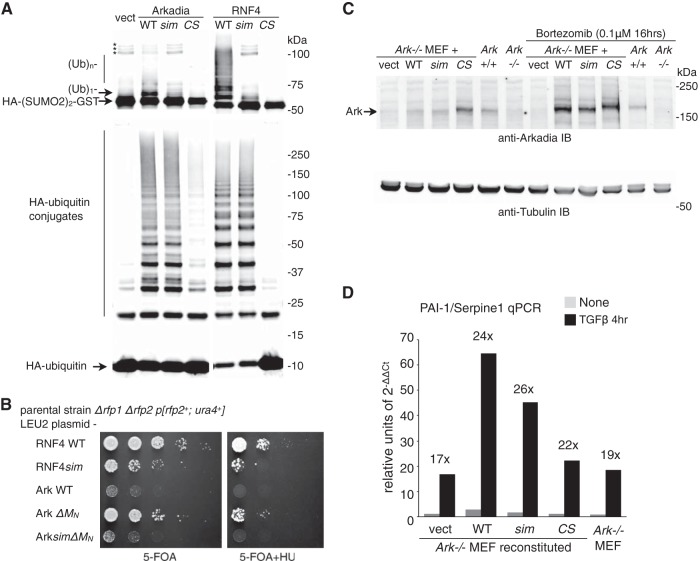

FIG 1.

Function of Arkadia's SUMO-binding domain is significant in vitro but insignificant in vivo. (A) SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) activity of Arkadia in an immunoprecipitation-coupled ubiquitin ligase assay. Flag-tagged Arkadia and its mutant forms (sim, sim13m [core hydrophobic residues, V298/V299/V300 in SIM1 and V380/V381/L383 in SIM3, changed to A]; CS, RING domain C966S mutant [change of C to S at position 966]) were immunoprecipitated in duplicates. The beads bound with the intact immune complex were used as the source for E3 in a ubiquitin ligase assay in vitro. The assay was conducted either with free ubiquitin (Ub) and an HA-tagged di-SUMO2–GST fusion protein as the substrates (top) for SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) activity or by using HA-tagged ubiquitin (bottom) for unspecified ligase activity. For both reactions, the products of the reaction mixture were analyzed with anti-HA antibody immunoblotting. *, nonspecific bands, likely aggregates of HA-(SUMO2)2-GST. (B) Results of plasmid shuffle, a yeast-based assay to examine the STUbL activity of RNF4, Arkadia, and their mutants (as indicated) in supporting the growth of the Δrfp1Δrfp2 double-mutant strain of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. RNF4sim, sim23m mutant of RNF4, with core hydrophobic residues, I50/V51/L53 in SIM2 and V63/V63/L65 in SIM2, changed to A; 5-FOA, 5-fluoroorotic acid; HU, hydroxyurea. (C) Retrovirus-reconstituted expression of mouse Arkadia proteins in Ark−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts. The reconstituted expression of Arkadia proteins (as indicated), as well as the expression of endogenous Arkadia in wild-type (Ark+/+) MEFs, was determined through anti-Arkadia antibody immunoblotting. The amount of Arkadia proteins with an intact RING domain is increased upon proteasome inhibitor (bortezomib) treatment. The expression of α-tubulin in the lysates was shown as a loading control. (D) TGFβ signaling in wild-type and reconstituted Ark−/− MEFs. Expression of endogenous PAI-1/Serpine1 before and after a 4-h TGFβ stimulation was examined with RT-qPCR. Data are shown in arbitrary units based on the expression level of PAI-1/Serpine1 relative to that of GAPDH (2−ΔΔCt, cycle threshold). Cell lines used in the experiment are as indicated.

We further compared Arkadia and RNF4 by testing whether Arkadia shares the conserved biological activity of the RNF4 family STUbLs, which has been highlighted by the fact that RNF4 can compensate the loss of its homologs, e.g., Rfp1 and Rfp2 in the fission yeast S. pombe (14, 35, 36). However, wild-type Arkadia failed to show any RNF4-like activity in a plasmid shuffle assay in the Δrfp1 Δrfp2 mutant strain (Fig. 1B). Here, we reasoned that with a much longer linear distance between the SIMs and RING in Arkadia, the coupling of SUMO binding and ubiquitylation may not be as direct as in RNF4 and, thus, cannot provide enough STUbL activity for yeast cells. Indeed, a compact version of Arkadia lacking a part of the linker region between the two domains (designated ArkΔMN) (see below and Fig. 3 for more details) showed significant RNF4-like activity in yeast, which, although not as robust as wild-type RNF4, was strictly dependent on SUMO binding (Fig. 1B). This suggests that the SIMs may be the only substrate-binding domain for an RNF4-like STUbL in yeast, as SIMs and the RING are the sole structures conserved among RNF4, ArkΔMN, and yeast Rfp1 and Rfp2; this yeast-based rescue assay may represent a functional approach for identifying additional STUbLs. In conclusion, while Arkadia can act as a putative STUbL in vitro through the combined activity of its SUMO-binding and RING domains, this activity may be suppressed in vivo by its linker region.

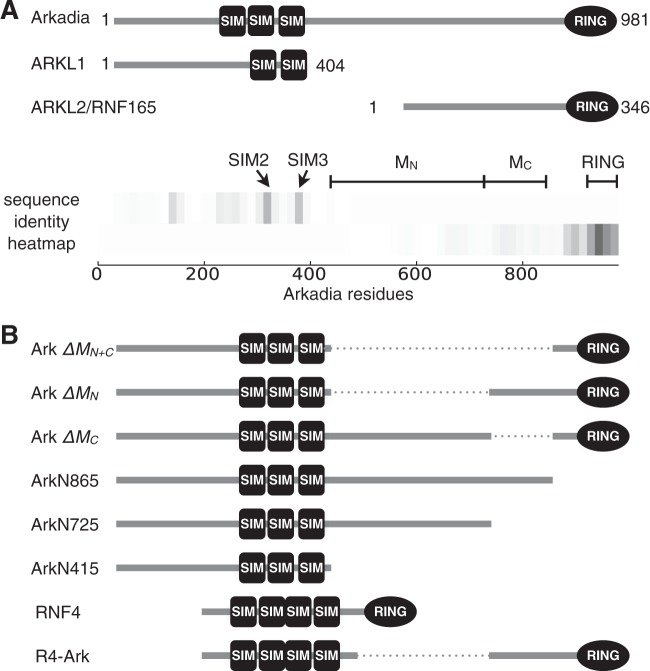

FIG 3.

Arkadia and the homologous Arkadia-like proteins (ARKL1 and ARKL2) are distinct in the middle region (M) of Arkadia between the SUMO-interacting motifs and the RING domain. (A) Domain structure of Arkadia, ARKL1, and ARKL2, with conserved SIMs and RING domain. A heat map (bottom) illustrates the conserved regions between the N-terminal half of Arkadia and ARKL1 and between the C-terminal half of Arkadia and ARKL2. The heat map was drawn using an array of identity scores assigned to each residue in Arkadia, based on the degree of local sequence identity it shares with ARKL1 or ARKL2 in a ClustalW alignment (actual alignment not shown); the gray scale (darkness) in the heat map corresponds to the degree of local sequence identity. The highly conserved SIM2, SIM3, and RING domain are as indicated. MN and MC denote two parts of the Arkadia M domain subject to mutational analyses in this study, described in the legend to panel B. (B) Diagrams of Arkadia mutants used in this study. In particular, ArkΔMN+C, ArkΔMN, and ArkΔMC refer to the deletion of residues 415 to 865, 415 to 725, or 725 to 865, respectively, in Arkadia; ArkN865 and ArkN725 are truncation mutants lacking the C terminus; R4-Ark is a chimeric fusion protein with the N-terminal 125 residues of RNF4 and the C-terminal 256 residues of Arkadia.

Gene expression profiling of TGFβ-stimulated transcriptome.

To determine the functional significance of the Arkadia SUMO-binding domain, we also compared the response to TGFβ in arkadia-null (Ark−/−) MEF cell lines (21, 28) that we stably reconstituted with both wild-type and the SIM and RING mutant forms of Arkadia (Fig. 1C, sim and CS, respectively). The expression levels of the exogenous proteins were comparable to the expression of endogenous Arkadia in wild-type MEFs and were stabilized by the RING domain mutation or by proteasome inhibition, indicating an autoubiquitylation-mediated turnover of the Arkadia protein (Fig. 1C). We measured the mRNA level of PAI-1 (Serpine1), a well-characterized TGFβ-stimulated gene (29), through RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1D). We found that both the Ark−/− MEFs and all the reconstituted cell lines showed robust PAI-1 RNA responses to TGFβ stimulation. In particular, while the relative amount of PAI-1 mRNA after a 4-h TGFβ treatment varied among the different cell lines, the degree of response upon TGFβ stimulation was similar. This is consistent with previous studies indicating that Arkadia is not an essential component in the TGFβ pathway (28).

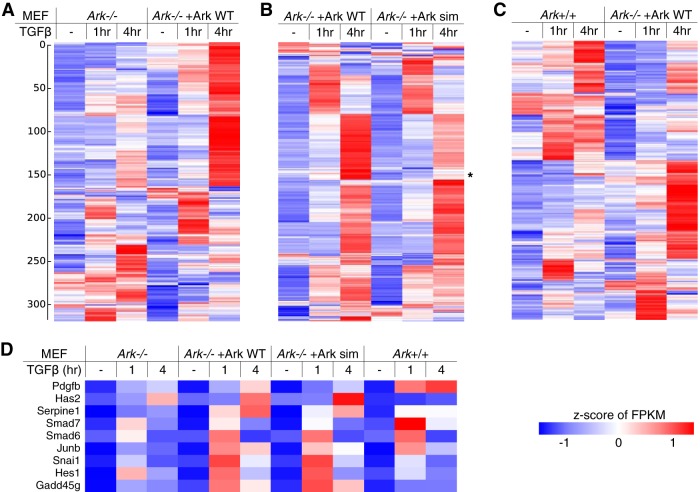

To determine the role of Arkadia in TGFβ signaling at the transcriptome level, we further compared the profiles of TGFβ-stimulated gene expression in Ark+/+, Ark−/−, and Arkadia (WT and sim mutant)-reconstituted Ark−/− MEFs. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was carried out using poly(A)-selected RNA samples from unstimulated cells and cells treated with TGFβ for 1 and 4 h. To represent the TGFβ-stimulated transcriptome, a list of 318 genes was selected on the basis of showing at least 2-fold TGFβ stimulation under at least one of the experimental conditions. This set of genes was subjected to several clustering analyses, and the results illustrated in heat maps (Fig. 2; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). We observed major clusters corresponding to TGFβ-upregulated genes at two different time points, consistent with a transient and dynamic nature of the TGFβ signaling. A comparison between Ark−/− and Arkadia-reconstituted Ark−/− MEFs again indicated that Arkadia is not essential for TGFβ signaling, as the gene activation profile was preserved during the time course (Fig. 2A and D). Nevertheless, reexpression of Arkadia in Ark−/− MEFs promoted TGFβ-induced expression of a number of genes at both time points (Fig. 2A and D), including some of the well-known immediate early genes stimulated by TGFβ (Fig. 2D), consistent with previous studies (37). On the other hand, MEFs reexpressing WT and sim mutant Arkadia show similar profiles of TGFβ stimulation (Fig. 2B and D). Although the heat map suggests a minor gene cluster (*) exhibiting relatively less induction by TGFβ in sim mutant-expressing MEFs, closer inspection of the FPKM values (see Table S1) at the cluster center revealed that this was largely due to elevated FPKM values in the untreated sim mutant sample and cannot be attributed to a reduced activity of the mutant. In addition, we found that the Arkadia-reconstituted MEFs did not completely mimic true wild-type (Ark+/+) MEFs with regard to the TGFβ-simulated transcriptome (Fig. 2C and D), indicating that the loss of Arkadia (presumably starting in the germ line) caused changes at the epigenetic level that could not be corrected by its reexpression in the MEFs (28).

FIG 2.

Arkadia promotes TGFβ signaling at the transcriptome level. Profiles of TGFβ-stimulated gene expression in Ark−/−, in wild-type and sim mutant Arkadia-reconstituted MEFs, and in Ark+/+ MEFs were obtained through RNA sequencing. (A to C) Heat maps illustrating the results of three separate hierarchical clustering analyses using the same list of 318 genes, all of which have an FPKM of ≥2 in all samples and show a TGFβ-induced activation of ≥2-fold at least once. Each clustering was calculated based on the standardized FPKM values (z-scores, scaled for each gene). Heat maps are drawn on a blue-white-red color scale corresponding to the z-score. The results of three hierarchical clustering analyses, as shown in three separate panels in Table S1 in the supplemental material, sorted the genes in different orders and resulted in different patterns for the same data set (i.e., the Ark−/−+Ark WT samples) in the heat maps. (D) The RNA-seq results for nine well-known TGFβ-stimulated genes are shown as a separate heat map.

In summary, our observations thus far did not indicate any major defect of the Arkadia sim mutant in vivo. We conclude that, while Arkadia plays a potentiating role in transcriptional activation downstream from the TGFβ pathway, it is not an essential component of the pathway, and the function of Arkadia SIMs cannot be readily revealed by analyses based on full-length proteins.

The linker between SIMs and RING distinguishes Arkadia from the paralogous ARKL1/ARKL2 and dictates specific function.

To understand how the linker region between the SIMs and RING influences Arkadia's function, we compared the sequences of Arkadia and the Arkadia paralogs ARKL1 and ARKL2 (Fig. 3A). ARKL1 essentially resembles the N-terminal half of Arkadia truncated at the end of the SUMO-binding domain, with a high degree of sequence identity corresponding to two of the Arkadia SIMs (SIM2 and SIM3). ARKL2, also known as RNF165, shares with Arkadia a nearly identical C terminus, including the RING domain. On the other hand, a large part of Arkadia between the SIMs and RING, consisting of residues ∼415 to ∼865, is unique and shows little similarity to either ARKL1 or ARKL2. We designate this linker region the M (middle) domain and divide it further into MN (residues 415 to 725) and MC (residues 725 to 865) (again based on sequence conservation, with MC showing a slightly higher-than-background similarity to ARKL2) (Fig. 3A). Accordingly, a series of Arkadia mutants were generated for a functional dissection of the M domain (Fig. 3B).

To first determine whether the structural similarity between Arkadia and ARKL1/ARKL2 is accompanied by similar cellular function, we compared their activation of the CAGA12-MLP-luciferase reporter (Fig. 4A). This reporter, derived from the Smad3-binding elements in the PAI-1/Serpine1 promoter (29), can be activated modestly by Arkadia alone and to a much greater extent by the combined expression of Arkadia and a constitutively active TGFβ type I receptor (an ALK5T204D mutant, herein referred to as TβR1*) (23, 24). With its broader dynamic range, the synergistic activation observed in the presence of TβR1* has been used as the main indicator of Arkadia activity in our study; this activity is also consistently dependent on the Arkadia RING domain in our experiments, as in the previous reports (Fig. 4A). Compared to Arkadia, neither coexpressed ARKL1 and ARKL2 nor an artificial ARKL1-ARKL2 fusion protein (ARKL1-2) showed any activity in this reporter assay (Fig. 4A). This suggests that the structures shared between Arkadia and the ARKL1/ARKL2 pair, including the SIMs and the RING domain, are insufficient for an Arkadia-specific activity; the M domain that is unique to Arkadia's structure may also be critical for its specific function.

To test this hypothesis, we then examined Arkadia mutants with M domain deletions using the same reporter assay (Fig. 4B). We found that ArkΔMN+C, which lacks the entire M domain, is indeed inactive, suggesting that the M domain is essential for the specific function of Arkadia. On the other hand, both ArkΔMN and ArkΔMC mutants retained some activity, but in clearly different manners. ArkΔMN appears only partially active in this assay, suggesting that the N-terminal portion of the M domain is necessary for a fully functional Arkadia. ArkΔMC, on the other hand, is as active as wild-type Arkadia; however, in contrast to both the wild type and ArkΔMN, the activity of ArkΔMC is strictly dependent on SUMO interaction, as the double mutant lacking both SIMs and MC showed a dramatic loss of activity (Fig. 4B). This suggests that a fully functional Arkadia relies on a redundant role of the SUMO-binding domain and MC; together, they promote a SUMO-binding-dependent activity of Arkadia.

We next examined whether the activities of the Arkadia mutants in the reporter assay correlated with their STUbL activity in vitro (Fig. 4C). We found that, even though Arkadia depends on the M domain for its biological activity, the functionally inactive ArkΔMN+C mutant showed the most robust SIM-dependent ubiquitin ligase activity against the di-SUMO2 substrate (Fig. 4C, lanes 6 and 7). This is probably because the internal deletion mutant can bring the bound SUMO substrate physically closer to the RING domain, consistent with the observed difference between Arkadia and RNF4 in their activities in vitro and in yeast (Fig. 1A and B). Thus, the transcriptional activation driven by Arkadia mutants does not correlate with their in vitro STUbL activity, indicating that Arkadia is not the equivalent of an RNF4-like STUbL in vivo.

The functional distinction between Arkadia and RNF4 was further exemplified in an RNF4-Arkadia chimeric protein named R4-Ark, which combines the SUMO-binding domain of RNF4 (including its nuclear localization signal [NLS]) and the C terminus of Arkadia, including the MC (Fig. 3). In the TGFβ reporter assay, R4-Ark was considerably more active than RNF4 itself, which was essentially null (Fig. 4D), demonstrating again that the M domain, especially MC, is crucial for specifying the function of Arkadia in the TGFβ pathway.

Multiple structures in Arkadia promote its colocalization with Polycomb bodies in U2OS cells.

To understand the function of the Arkadia M domain, we have also investigated how it may affect the subcellular localization of Arkadia. We noticed consistently that transiently expressed Arkadia formed distinct nuclear foci in cultured U2OS cells. In particular, the RING mutant of Arkadia exhibited a more stable nuclear pattern than the wild type, which in ∼46% of the cells was found in both nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). As wild-type Arkadia was expressed at a much lower level than the RING mutant and was stabilized by proteasome inhibition (Fig. 1C) (38), we reasoned that the wild type is unstable due to autoubiquitylation and, thus, has a more dynamic subcellular localization. For a static view of its E3-independent nuclear localization, we have focused on the RING domain mutants of Arkadia in our imaging experiments.

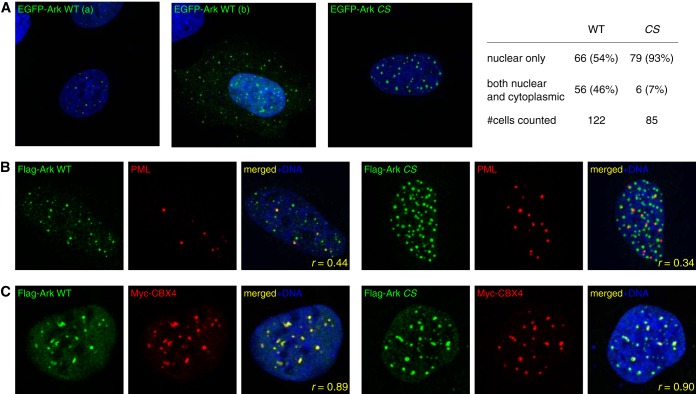

FIG 5.

Nuclear localization of Arkadia with respect to PML nuclear bodies and Polycomb bodies. (A) Immunofluorescence images of U2OS cells expressing wild-type (WT) or RING domain mutant (CS) of Arkadia as EGFP fusion proteins (green). Nuclear DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). WT Arkadia was found to be either exclusively nuclear (a) or both cytoplasmic and nuclear (b) in U2OS cells; the CS mutant form was mostly nuclear. The images shown are representative of images acquired from multiple independent experiments, the statistics of which are given at the right (#cells counted, number of cells counted). (B) Nuclear localization of Arkadia proteins compared with localization of PML nuclear bodies (NBs) in U2OS cells. Flag-tagged Arkadia was stained with an anti-Flag antibody (green); PML NBs were stained with anti-PML monoclonal antibody PG-M3 (red). r, Pearson's correlation coefficient between the red and green channels from the image (200 by 200 pixels), calculated using the pixel intensity of all 20,000 pixels. (C) Nuclear localization of Arkadia proteins compared with localization of Polycomb (Pc) bodies in U2OS cells. Flag-tagged Arkadia was stained with an anti-Flag antibody (green); Pc bodies were visualized by anti-Myc antibody immune staining of a cotransfected Myc-tagged CBX4 (red). r, Pearson's correlation coefficient between the red and green channels as described for panel C.

To determine the identity of the Arkadia nuclear foci, we carried out immunofluorescence microscopy using transfected U2OS cells. A fraction of the Arkadia foci costained with endogenous PML nuclear bodies (PML NBs) (Fig. 5B). This is consistent with a number of studies suggesting that PML NBs are major aggregation sites for SUMO-binding proteins, especially in arsenic trioxide (As2O3)-treated cells, where significant Arkadia-PML colocalization has been reported (8–11, 15, 39). However, we also observed in U2OS cells that a subset of Arkadia foci did not costain with PML NBs. Instead, we found that all Arkadia foci, regardless of PML NB colocalization, overlapped with Polycomb (Pc) bodies, as they costained with a coexpressed Polycomb group protein, CBX4/Pc2 (Fig. 5C), a component of the Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and also a source of significant sumoylation activities that may be attributed to the reported SUMO ligase and SUMO-binding activities of the CBX4/Pc2 protein itself (7, 10, 12, 40, 41).

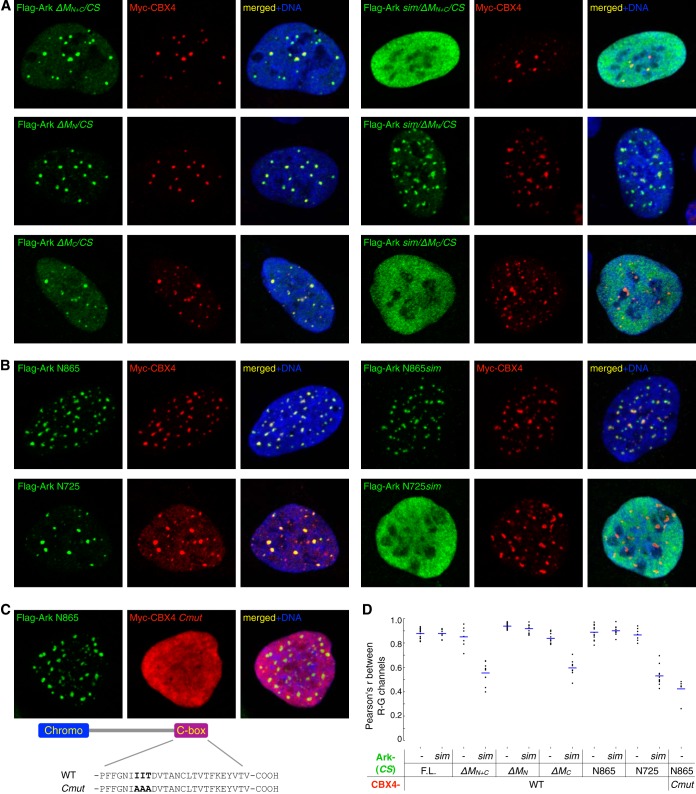

Next, to determine whether the Arkadia M domain plays a role in the Polycomb body association, we examined a series of Arkadia mutants, including the internal deletion mutants ArkΔMN+C, ArkΔMN, and ArkΔMC, as well as the truncation mutants ArkN865 and ArkN725 (lacking the C terminus from residue 865 or 725), for their subcellular localization (Fig. 3B and Fig. 6). In particular, we compared pairs of Arkadia constructs either with or without an intact SUMO-binding domain (SBD). When the entire M domain was missing, the resulting Arkadia mutant (ArkΔMN+C) was still recruited to the Pc bodies but in a strictly SIM-dependent manner; instead of forming distinct nuclear foci, the sim/ArkΔMN+C double mutant showed a completely diffused nuclear localization (Fig. 6A, top panels), indicating that both the SBD and the M domain can target Arkadia to Pc bodies. In contrast, when only the MN region was missing, the resulting mutant (ArkΔMN) was localized to Pc bodies regardless of an intact SBD (Fig. 6A, middle row), suggesting it is the MC region that targets Arkadia to Pc bodies in the absence of SUMO binding. Indeed, the Pc body localization of ArkΔMC was again dependent on SUMO binding (Fig. 6A, bottom row). Consistent with this, we found that the Arkadia N865 fragment, with an intact M domain, was recruited to Pc bodies regardless of mutation in the SBD, whereas the N725 fragment, with MC missing, was focused on Pc bodies only with a wild-type SBD but was diffused in the nucleus when the SIMs were also mutated (Fig. 6B). As a negative control, we examined the ArkN865 signal in the presence of a CBX4 mutant (Cmut), in which three beta-strand-forming residues, I541, I542, and T543, are replaced with Ala in the C-box, a C-terminal motif known to be essential for the Pc body recruitment of CBX4 (41). We found that the Arkadia protein still formed nuclear foci in the presence of the CBX4 mutant, which showed a diffused nuclear localization, indicating that this Pc body-defective CBX4 mutant is incapable of sequestering Arkadia away from endogenous Pc bodies (Fig. 6C). Last, as a quantitative evaluation of colocalization, we computed the pixel-by-pixel covariance of the Arkadia and CBX4 immunofluorescent signals, in the form of Pearson's correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) between the pixel intensities of the green and red channels (42). Images showing the colocalization of a pair of Arkadia/CBX4 proteins gave rise to an r of around 0.85, indicating a specific enrichment of both proteins at nearly all nuclear foci; in contrast, images of noncolocalizing pairs (with one protein showing a diffused pattern in the nucleus) resulted in an r of around 0.5, a degree of correlation reflecting only the nuclear localization of both proteins but with no significant coenrichment at the nuclear foci (Fig. 6D). In conclusion, we identify Arkadia as a Polycomb body-associated protein; the M domain, especially MC, and the SBD in Arkadia are functionally redundant—together, they not only specify the activity of Arkadia in transcriptional activation but also provide sufficient avidity for directing Arkadia to Polycomb bodies.

FIG 6.

Recruitment of Arkadia to Polycomb bodies is directed by its SUMO-binding domain and M domain. (A and B) Nuclear localization of Arkadia mutants (as indicated) combining M domain deletions, C-terminal truncations, and point mutations in the SUMO-binding domain. Flag-tagged Arkadia constructs (green) were coexpressed with Myc-tagged CBX4 (red) in U2OS cells and visualized through immunofluorescence microscopy. Nuclear DNA (blue) was stained with Hoechst 33342. (C) Polycomb body localization of ArkN865 in the presence of a nuclear-diffused, C-box mutant form (Cmut) of CBX4 (red). Diagram at bottom illustrates the point mutations in the C-box of CBX4 that replaced three residues with Ala. (D) Quantitative measure of the degree of colocalization between Arkadia and CBX4 proteins. Each dot in the plot corresponds to the Pearson's correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) between the red and green channels from a cropped image (200 by 200 pixels, as presented in this figure and in Fig. 5), calculated using the respective pixel intensities of all 20,000 pixels. Horizontal lines mark the average of Pearson's r from multiple images in each experimental group (as indicated).

A polyhistidine motif participates in avidity-driven subcellular targeting of Arkadia.

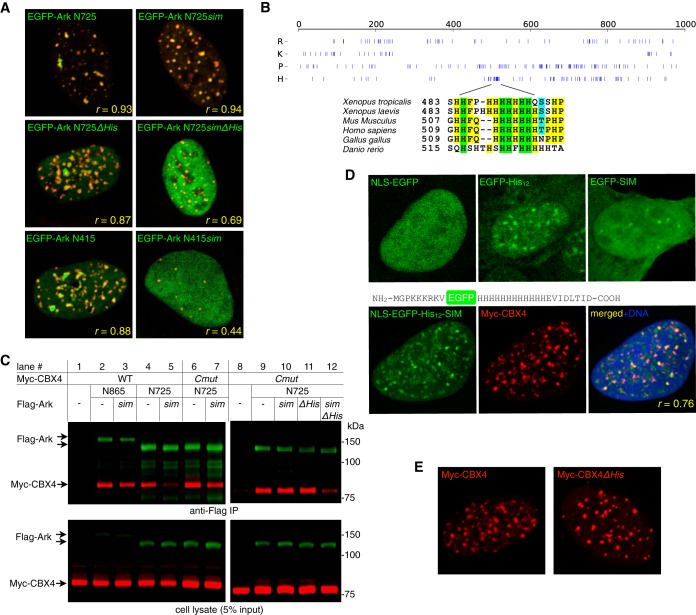

In dissecting the relationship between Arkadia structures and its nuclear localization, we noticed that, in contrast to the Flag-tagged ArkN725 (Fig. 6B), EGFP-tagged ArkN725 did not rely on the SIMs to localize to Pc bodies (Fig. 7A and data not shown). We hypothesized that additional motifs concealed in the MN region may cooperate with the SBD and MC in targeting Arkadia to the Pc body; the role of such motifs may become detectable only when it is presented in a multivalent form due to, e.g., oligomerization of the EGFP tag. We note that the sequence of the M domain shows not only a complete lack of lysine (38) but also a significant enrichment of histidine and proline residues (H, 12%, and P, 16%) compared to their average abundance in proteins (H, ∼2.5%, and P, ∼5%) (43) (Fig. 7B). While understanding the entire His/Pro-rich structure is beyond our scope here, we nevertheless tested the potential importance of a poly-His motif in the MN region of Arkadia (Fig. 7B) (21). This was in light of a study suggesting that, although their presence in mammalian proteomes is rare, poly-His motifs may participate in the assembly of nuclear structures (44). Indeed, when this poly-His motif was removed from EGFP-ArkN725, the mutant form (EGFP-N725ΔHis [ΔHis, deletion of residues 492 to 521 in Arkadia]) again became dependent on the SBD for Pc body localization, in a manner comparable to the results for EGFP-ArkN415, which lacks the entire M domain (Fig. 7A, middle and bottom). Therefore, as in a typical avidity-driven protein complex formation, the poly-His motif in Arkadia is not essential but participates in targeting Arkadia to Pc bodies.

FIG 7.

A polyhistidine motif in Arkadia contributes to the avidity-driven subcellular targeting of Arkadia. (A) Nuclear localization of Arkadia mutants as EGFP fusion proteins (green) with respect to localization of coexpressed Myc-tagged CBX4 (red) in U2OS cells; images show the merged green and red channels. ΔHis, deletion of residues 492 to 521 in Arkadia. r, Pearson's correlation coefficient between the red and green channels, calculated as described in the legends to Fig. 5 and 6. (B) Arkadia M domain is His and Pro rich. The plot shows the distribution of Arg, Lys, Pro, or His along the sequence of Arkadia. The alignment below the plot highlights the poly-His motif in Arkadia homologs from human, mouse, frog, chicken, and zebrafish. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of Arkadia and CBX4. Myc-tagged CBX4 and its C-box mutant (Cmut) were coexpressed with Flag-tagged ArkN865, ArkN725, and their mutants (as indicated) in 293T cells. Immunoprecipitation was carried out against Arkadia using anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (M2)-conjugated agarose beads. Proteins in the precipitated immune complex or in the cell lysate were analyzed in anti-Flag (green) or anti-Myc (red) antibody dual-color immunoblots. (D) Synergistic activity of poly-His motif and SIM in promoting a Polycomb body association. Top, control images showing EGFP fusions with the NLS, His12, or SIM alone. Bottom, sequence diagram and subcellular localization of NLS-EGFP-His12-SIM, a synthetic construct containing the fusion of EGFP with a nuclear localization signal (NLS; based on that of the SV40 large T antigen, PKKKRKV), a poly-His motif (His12), and a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM; based on the core sequence EVIDLTID of the SIM in human PIAS1), coexpressed with Myc-CBX4 (red). r, Pearson's correlation coefficient between the red and green channels calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. (E) A comparison of nuclear foci formed by wild-type CBX4 and CBX4ΔHis, a mutant form missing its poly-His motif (residues 378 to 400), in U2OS cells.

To examine whether the Arkadia poly-His motif is involved in the physical association with Pc body proteins, we carried out immunoprecipitation experiments in 293T cells to assay the M domain-mediated association between Arkadia and the Pc body protein CBX4. Consistent with the functional redundancy between SBD and MC, only ArkN725 and not ArkN865 coprecipitated with wild-type CBX4 in a SIM-dependent manner (Fig. 7C, lanes 1 to 5). Counterintuitively, the C-box mutant of CBX4 also coprecipitated with ArkN725, suggesting that such coimmunoprecipitation was not restricted to proteins associated with the cytologically defined Pc bodies (as in Fig. 6C). Nevertheless, this Pc body-independent association relies on the simultaneous presence of both the SIMs and the poly-His motif, as only the sim/ΔHis double mutant showed a diminished coprecipitation with the CBX4 mutant (Fig. 7C, lane 12). This again indicates a contribution of the poly-His motif in the association between Arkadia and Pc bodies.

We explored this idea further using a synthetic construct containing a SIM, a poly-His motif (His12), and the nuclear localization sequence of the simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen, all fused to EGFP. In contrast to the controls using EGFP tagged with the His12 motif or SIM alone (Fig. 7D, top) (44), this protein (NLS-EGFP-His12-SIM) formed discrete nuclear foci in U2OS cells that partially overlapped with the CBX4-labeled Pc bodies (Fig. 7D, bottom). Last, while CBX4 also contains a poly-His motif, the CBX4ΔHis mutant was indistinguishable from the wild type in the formation of nuclear foci, suggesting that the motif is also dispensable for the Pc body localization of CBX4 (Fig. 7E). We conclude that the poly-His motifs in both Arkadia and CBX4 act together with other motifs as an ensemble to promote the Pc body localization, just as their SIMs do.

Dual function of Arkadia M domain in the activation of a methylation-silenced promoter.

Our study suggests that Arkadia is targeted to Polycomb bodies and promotes transcriptional activation through the combined activity of its SBD and M domains. Since Polycomb bodies, and sumoylation in general, are known to be associated with gene silencing and the maintenance of heterochromatin regions (45, 46), Arkadia may be involved in the recognition of a subset of transcriptionally silenced yet TGFβ-responsive promoters. We were encouraged by a recent functional screen identifying RNF4 as a driver for the reactivation of in vitro methylated reporters, which indicates that a potential function of RNF4 is to promote CpG demethylation (47). Although the RNF4 function is more broadly conserved throughout eukaryotes than CpG methylation, a STUbL may recognize gene-silencing signals through its SIMs, including those caused by CpG methylation (48, 49). We reasoned that using CpG-methylated reporter plasmids would provide a means of controlled epigenetic silencing in vitro for investigating a STUbL-like activity in Arkadia. We therefore examined how Arkadia activates the methylation-silenced TGFβ pathway CAGA12 luciferase reporter and, in particular, how Arkadia SIMs influence such activity.

Similar to our observations using the unmethylated reporter (Fig. 4B), wild-type Arkadia activated the methylated CAGA12 reporter, and the contribution of SBD to this activation was rather insignificant (Fig. 8A). Also consistently, the M domain was essential for Arkadia function, as deletion of the entire M domain (ΔMN+C) completely abolished such activity. In contrast, however, the deletion of MN or MC alone (ΔMN or ΔMC) resulted in greatly elevated activity against the methylated reporter (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, in both ArkΔMN and ArkΔMC mutants, we found that the SIMs were absolutely necessary for their activity against the methylated CAGA12 luciferase (Fig. 8A). This is different from their activity against the unmethylated reporter (Fig. 4B), where ArkΔMN showed weaker-than-wild-type and SIM-independent activity and ArkΔMC showed similar-to-wild-type yet strictly SIM-dependent activity. In addition, we again found little activity of RNF4 against the methylated CAGA12 reporter (Fig. 8A). On the other hand, the chimeric protein R4-Ark, which contains MC, showed much higher activity that was also dependent on the SUMO-binding domain from RNF4 (Fig. 8A). This shows that a STUbL-like activity against a TGFβ pathway-specific promoter requires both an SBD (even an exogenous one with a different configuration of SIMs) and MC. We conclude that the SBD of Arkadia allows for efficient targeting to epigenetically silenced promoters downstream from the TGFβ pathway, where SUMO-targeted ubiquitylation may be a crucial mechanism for transcriptional activation. Moreover, while the M domain is essential for a biologically active Arkadia, our data also suggested a dual role for it in Arkadia's activity toward the methylation-silenced promoter, which appeared to be inhibited by individual parts of the M domain (Fig. 8B).

Arkadia promotes transcriptional repression.

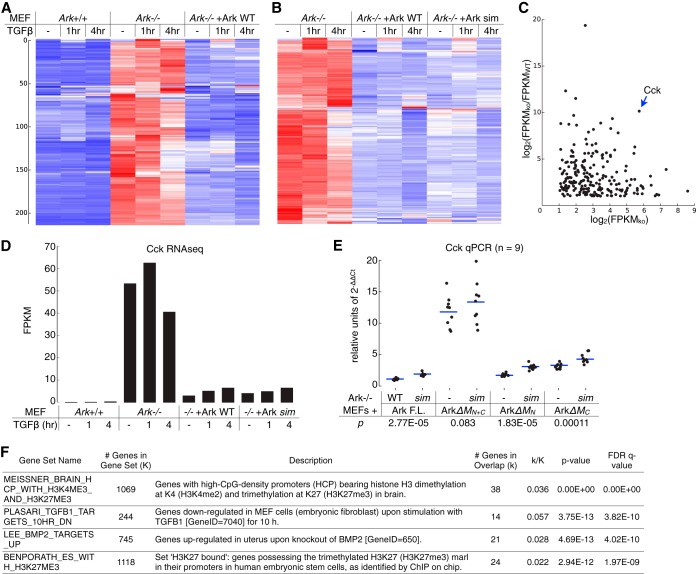

Polycomb body formation is in general associated with the maintenance of gene silencing. To further understand the significance of Arkadia's Pc body localization, we also investigated its possible role as a transcriptional repressor. Indeed, our RNA-seq experiment revealed that the expression of certain genes was elevated in Ark−/− MEFs compared to their expression in wild-type MEFs, and many were again downregulated upon reexpression of Arkadia, indicating that such genes were genuinely suppressed by Arkadia. The Arkadia-suppressed transcriptome can thus be represented by a list of 213 genes selected on the basis of exhibiting at least 50% less gene expression in both wild-type and Arkadia-reconstituted MEFs than in Ark−/− MEFs (Fig. 9; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). This list contains genes with downward movement after a 4-h TGFβ treatment in Ark−/− MEFs, consistent with the gene repression function of the TGFβ pathway (50) (Fig. 9A). Moreover, genes that were not influenced by TGFβ were also found to be suppressed by Arkadia (Fig. 9A), indicating that the Arkadia-mediated repression can be both TGFβ dependent and TGFβ independent. Nearly identical profiles of Arkadia-mediated suppression are found in cells expressing either the WT or the sim mutant (Fig. 9B; see Table S2), consistent with our other observations demonstrating that multiple motifs provide redundant activity for Arkadia function.

FIG 9.

Arkadia-mediated transcriptional repression. (A and B) Profiles of Arkadia-mediated transcriptional suppression in Ark+/+, Ark−/−, and arkadia-reconstituted MEFs were obtained through RNA sequencing. The heat maps illustrate the results of two separate hierarchical clustering analyses using the same list of 213 genes that exhibited an expression level of ≥2 FPKM in Ark−/− MEFs and at least 50% repression in both Ark+/+ and Arkadia-reconstituted Ark−/− MEFs (as indicated). Each clustering was calculated based on the standardized FPKM values (z-scores), scaled for each gene. Heat maps are shown on a blue-white-red color scale corresponding to the z-score, as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The sorted lists of genes after each hierarchical clustering are presented as separate panels in Table S2 in the supplemental material. (C to E) Cholecystokinin (Cck) is a major Arkadia-suppressed gene in MEFs. (C) Based on RNA-seq results for the 213 selected genes in no-TGFβ samples, a log2-scaled scatter plot illustrates the degree of Arkadia-mediated suppression (FPKMKO/FPKMWT ratio, where FPKMKO is the expression level in Ark−/− MEFs and FPKMWT is the expression level in Ark+/+ MEFs) for each with respect to FPKMKO. (D) The FPKM values for the Cck gene in all samples are shown as a bar graph. (E) Additional expression analysis of Cck using RT-qPCR was carried out in Ark−/− MEFs reexpressing various Arkadia proteins (as indicated). The qPCR results were calculated based on the expression levels of Cck relative to that of Gapdh; results from multiple independent qPCR assays were plotted as dots slightly scattered along the x axis for an ensemble view of all data points and with their mean values highlighted by horizontal lines (E). The significance (P value) of the difference between the activity of an Arkadia protein and its corresponding sim mutant was estimated based on a paired, one-tailed Student's t test. (F) Overlaps between the Arkadia-suppressed genes and gene sets in Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). The query returned the top 20 gene sets showing significant overlaps (P < 6e−12). The 4 gene sets presented indicate the enrichment for genes with histone H3K27 trimethylation or genes downregulated by the TGFβ pathway. The complete results are shown as a panel in Table S2 in the supplemental material. FDR, false discovery rate; q value, minimum FDR at which the test was significant.

From this list, we identified Cholecystokinin (Cck) (51) as a major Arkadia-suppressed gene in MEFs: it was not only expressed at a high level in Ark−/− MEFs but also suppressed to a high degree in both Ark+/+ and Arkadia-reconstituted Ark−/− MEFs (Fig. 9C and D; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material), making it an ideal reporter gene for evaluating the function of the Arkadia M domain in transcriptional repression. We therefore used quantitative RT-PCR to measure endogenous Cck expression in Ark−/− MEFs reexpressing the M domain deletion mutants and compared the effects of these mutants with that of full-length Arkadia (Fig. 9E). Consistent with its function both in CAGA12 reporter assays and in Arkadia's Pc body recruitment, the M domain is also essential for Arkadia's gene repression function, as the deletion of the entire M domain (ΔMN+C) resulted in an ∼12-fold increase of Cck expression (Fig. 9E). The effect was more subtle with the deletion of MN or MC alone (ΔMN or ΔMC) or mutation of the SIMs, as these modifications did not cause a dramatic loss of Cck gene repression. Nonetheless, the sim mutants of full-length Arkadia, ArkΔMN, and ArkΔMC all exhibited a small but reproducible defect in suppressing Cck transcription compared to the effects of their wild-type SIM counterparts (P values of 2.77e−5, 1.83e−5, and 0.00011, respectively). Overall, the activity profiles of these mutants in Arkadia-mediated suppression of Cck gene expression are largely correlated with their activities in CAGA12 reporter assays and in mediating Arkadia's Pc body recruitment.

Furthermore, cross-referencing with the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (52) revealed that the list of Arkadia-suppressed genes is enriched with genes previously identified as containing promoters of trimethylated histone H3 at K27 (H3K27me3), a Polycomb-associated histone mark (Fig. 9C; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). Specifically, significant overlaps (P < 5e−12) were found in two published data sets: (i) an overlap of 38 genes were found in a list of 1,069 genes that reportedly contain promoters bearing high-CpG density and histone modifications H3K4me2 and H3K27me3 (53) and (ii) a separate study identified 1,118 genes that contain the H3K27me3 histone mark at their promoter region, 24 of which overlapped with our Arkadia-suppressed gene list (54). Also consistent with our observations, significant overlaps (P < 5e−13) were found with gene sets negatively regulated by TGFβ or BMP2 (Fig. 9F; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material) (55, 56). In conclusion, besides its role in promoting TGFβ-induced transcriptional activation, Arkadia also plays a role in transcriptional repression. The Arkadia-suppressed genes display a molecular signature that is highly correlated with Polycomb-associated epigenetic modification, consistent with the Arkadia's Polycomb body association observed in our study. Moreover, we suggest that Arkadia's activity in both transcriptional activation and repression may relate to the dual role played by its M domain in its activity against CpG-methylated transcription reporter (Fig. 8). We speculate that the conformation of the M domain is dynamically regulated in Arkadia's tertiary structure in order to support its functional duality.

DISCUSSION

We took an analytical approach to define the function of the SUMO-binding domain (SBD) in Arkadia and found that it is part of an ensemble of structural modules for both the subcellular targeting and the biological activity of Arkadia. Thus, Arkadia is a much more complex STUbL than RNF4 in transcriptional control. While this avidity-driven subcellular targeting allows Arkadia's biological activity to be regulated in both a SUMO-dependent and a SUMO-independent manner, our data suggest that SUMO binding may provide a particular advantage for targeting Arkadia to specific promoters, whose epigenetic silencing is maintained by Polycomb repressive complexes or DNA methylation (Fig. 8), and that Arkadia's subnuclear localization at Polycomb bodies may allow Arkadia to exhibit both activating and inhibitory activities in regulating gene expression.

The Polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 are two major biochemically characterized complexes formed by Polycomb group proteins. Both complexes contain histone modification activities, generating monoubiquitylated histone H2A (H2AK119Ub) or methylated histone H3 (e.g., H3K27me1, -2, and -3), respectively. PRC1 also contains chromodomain proteins, such as CBX4, that recognize lysine-methylated histones and is thus considered the reader of epigenetic marks written by PRC2. These activities together mediate the silencing of Polycomb target genes (57–59). Polycomb (Pc) bodies are cytologically defined nuclear bodies formed by components of PRC1 (such as CBX4) in certain types of cells; they are recognized as the aggregation of many copies of PRC1, reflecting the clustering of PRC1-targeted genomic loci in a three-dimensionally organized nucleus (6, 58, 60). Accordingly, the observed Pc body localization of Arkadia may also reflect a broader association with PRC1-occupied loci than with the visible Pc bodies. In addition, while we suggest that Arkadia is involved in the control of PRC1-targeted genes downstream from the TGFβ pathway, we did not observe any effect of TGFβ treatment on the number or size of Pc bodies or Arkadia's association with them (data not shown), indicating that the PRC1 complex is not altered by the TGFβ signaling but, rather, serves as a platform for other signal-responsive components of the pathway, where Arkadia substrates have been found. In this sense, the PRC1 complex may prime the activation of TGFβ-responsive genes rather than acting merely as a perpetual gene-silencing machinery.

Gene silencing by CpG methylation is mainly achieved through proteins containing a methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD), which in turn may mediate the assembly of corepressor complexes on methylated CpG (61). It is still an ongoing effort to understand how the interaction between the Polycomb- and CpG methylation-mediated gene-silencing systems shapes the epigenetic landscape of an entire mammalian genome (62). While both CpG methylation and PRC complexes at CpG islands (CGIs) can maintain transcriptional silencing, there appears to be a mutual exclusiveness between the DNA methylation at a CGI and Polycomb occupation (63–66). However, the DNA-demethylating enzyme TET1 is found to associate with CGIs through its CXXC domain that binds to unmethylated CpGs, indicative of a dynamic methylation-demethylation cycle on CGIs (67). Both gene-silencing systems have been implicated in TGFβ signaling: Bmi1, a RING domain ubiquitin ligase component of PRC1, was found to regulate the transcriptional response downstream from the TGFβ/BMP signaling pathway (68), and active demethylation was observed at the CpG-rich region of the p15INK5b promoter upon TGFβ stimulation (69). Future investigations in this direction, such as a genome-scale mapping of the epigenetic structures on genes specifically controlled by Arkadia, may help to explain how Arkadia coordinates both transcriptional activation and repression and close the conceptual gap between the molecular activities of Arkadia and the arkadia phenotype its mutation causes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vasso Episkopou for kindly providing arkadia−/− MEFs, Carl-Henrik Heldin for the CAGA12 luciferase reporter, Clodagh O'Shea for human CBX4 cDNA, Ze'ev Ronai for HA-tagged ubiquitin cDNA, Chunmei Zhao for assistance in the preparation of retroviruses, Manching Ku of Helmsley Center for Genomic Medicine for RNA sequencing, Chris Benner (homer.salk.edu) for lending expertise in data analysis and computation, and members of the Waitt Advanced Biophotonics Center Core Facility for assistance in imaging. We thank Jill Meisenhelder for the anti-Myc antibody (9E10) ascites, Evan Hsia for technical assistance, and other members of the Hunter laboratory for helpful discussion. We acknowledge the large body of work on epigenetic control by Polycomb and CpG-methylation that we are unable to cite thoroughly because of space limitations.

This study was supported by NIH grants CA14195, CA80100, and CA82683 to T.H. and the Helmsley Center for Genomic Medicine; T.H. is a Frank and Else Schilling American Cancer Society Professor and holds the Renato Dulbecco Chair in Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00036-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cubenas-Potts C, Matunis MJ. 2013. SUMO: a multifaceted modifier of chromatin structure and function. Dev. Cell 24:1–12. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Veen AG, Ploegh HL. 2012. Ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81:323–357. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-093010-153308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flotho A, Melchior F. 2013. Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82:357–385. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061909-093311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matunis MJ, Zhang XD, Ellis NA. 2006. SUMO: the glue that binds. Dev. Cell 11:596–597. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jentsch S, Psakhye I. 2013. Control of nuclear activities by substrate-selective and protein-group SUMOylation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 47:167–186. 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao YS, Zhang B, Spector DL. 2011. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends Genet. 27:295–306. 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagey MH, Melhuish TA, Wotton D. 2003. The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell 113:127–137. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00159-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sternsdorf T, Jensen K, Will H. 1997. Evidence for covalent modification of the nuclear dot-associated proteins PML and Sp100 by PIC1/SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 139:1621–1634. 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddy MN, Howe K, Etkin LD, Solomon E, Freemont PS. 1996. PIC 1, a novel ubiquitin-like protein which interacts with the PML component of a multiprotein complex that is disrupted in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Oncogene 13:971–982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Vega L, Frobius K, Moreno R, Calzado MA, Geng H, Schmitz ML. 2011. Control of nuclear HIPK2 localization and function by a SUMO interaction motif. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813:283–297. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin DY, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Kuo HY, Chang CC, Chao TT, Ho CC, Chen YC, Lin TP, Fang HI, Hung CC, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Chang KS, Maul GG, Shih HM. 2006. Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol. Cell 24:341–354. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merrill JC, Melhuish TA, Kagey MH, Yang SH, Sharrocks AD, Wotton D. 2010. A role for non-covalent SUMO interaction motifs in Pc2/CBX4 E3 activity. PLoS One 5:e8794. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun H, Hunter T. 2012. Poly-small ubiquitin-like modifier (polySUMO)-binding proteins identified through a string search. J. Biol. Chem. 287:42071–42083. 10.1074/jbc.M112.410985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun H, Leverson JD, Hunter T. 2007. Conserved function of RNF4 family proteins in eukaryotes: targeting a ubiquitin ligase to SUMOylated proteins. EMBO J. 26:4102–4112. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erker Y, Neyret-Kahn H, Seeler JS, Dejean A, Atfi A, Levy L. 2013. Arkadia, a novel SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase involved in PML degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33:2163–2177. 10.1128/MCB.01019-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen SL, Hansen RK, Wagner SA, van Cuijk L, van Belle GJ, Streicher W, Wikstrom M, Choudhary C, Houtsmuller AB, Marteijn JA, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N. 2013. RNF111/Arkadia is a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase that facilitates the DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 201:797–807. 10.1083/jcb.201212075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Namanja AT, Li YJ, Su Y, Wong S, Lu J, Colson LT, Wu C, Li SS, Chen Y. 2012. Insights into high affinity small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) recognition by SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) revealed by a combination of NMR and peptide array analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 287:3231–3240. 10.1074/jbc.M111.293118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly CE, Thymiakou E, Dixon JE, Tanaka S, Godwin J, Episkopou V. 2013. Rnf165/Ark2C enhances BMP-Smad signaling to mediate motor axon extension. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001538. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosendorff A, Sakakibara S, Lu S, Kieff E, Xuan Y, DiBacco A, Shi Y, Gill G. 2006. NXP-2 association with SUMO-2 depends on lysines required for transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5308–5313. 10.1073/pnas.0601066103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hecker CM, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I. 2006. Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 281:16117–16127. 10.1074/jbc.M512757200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Episkopou V, Arkell R, Timmons PM, Walsh JJ, Andrew RL, Swan D. 2001. Induction of the mammalian node requires Arkadia function in the extraembryonic lineages. Nature 410:825–830. 10.1038/35071095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederlander C, Walsh JJ, Episkopou V, Jones CM. 2001. Arkadia enhances nodal-related signalling to induce mesendoderm. Nature 410:830–834. 10.1038/35071103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy L, Howell M, Das D, Harkin S, Episkopou V, Hill CS. 2007. Arkadia activates Smad3/Smad4-dependent transcription by triggering signal-induced SnoN degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:6068–6083. 10.1128/MCB.00664-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koinuma D, Shinozaki M, Komuro A, Goto K, Saitoh M, Hanyu A, Ebina M, Nukiwa T, Miyazawa K, Imamura T, Miyazono K. 2003. Arkadia amplifies TGF-beta superfamily signalling through degradation of Smad7. EMBO J. 22:6458–6470. 10.1093/emboj/cdg632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Scolan E, Zhu Q, Wang L, Bandyopadhyay A, Javelaud D, Mauviel A, Sun L, Luo K. 2008. Transforming growth factor-beta suppresses the ability of Ski to inhibit tumor metastasis by inducing its degradation. Cancer Res. 68:3277–3285. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Rui H, Wang J, Lin S, He Y, Chen M, Li Q, Ye Z, Zhang S, Chan SC, Chen YG, Han J, Lin SC. 2006. Axin is a scaffold protein in TGF-beta signaling that promotes degradation of Smad7 by Arkadia. EMBO J. 25:1646–1658. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagano Y, Mavrakis KJ, Lee KL, Fujii T, Koinuma D, Sase H, Yuki K, Isogaya K, Saitoh M, Imamura T, Episkopou V, Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. 2007. Arkadia induces degradation of SnoN and c-Ski to enhance transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282:20492–20501. 10.1074/jbc.M701294200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mavrakis KJ, Andrew RL, Lee KL, Petropoulou C, Dixon JE, Navaratnam N, Norris DP, Episkopou V. 2007. Arkadia enhances Nodal/TGF-beta signaling by coupling phospho-Smad2/3 activity and turnover. PLoS Biol. 5:e67. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM. 1998. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. 17:3091–3100. 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forsburg SL, Rhind N. 2006. Basic methods for fission yeast. Yeast 23:173–183. 10.1002/yea.1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liew CW, Sun H, Hunter T, Day CL. 2010. RING domain dimerization is essential for RNF4 function. Biochem. J. 431:23–29. 10.1042/BJ20100957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao C, Teng EM, Summers RG, Jr, Ming GL, Gage FH. 2006. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 26:3–11. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29:15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. 2010. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28:511–515. 10.1038/nbt.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prudden J, Pebernard S, Raffa G, Slavin DA, Perry JJ, Tainer JA, McGowan CH, Boddy MN. 2007. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases in genome stability. EMBO J. 26:4089–4101. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosoy A, Calonge TM, Outwin EA, O'Connell MJ. 2007. Fission yeast Rnf4 homologs are required for DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 282:20388–20394. 10.1074/jbc.M702652200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Briones-Orta MA, Levy L, Madsen CD, Das D, Erker Y, Sahai E, Hill CS. 2013. Arkadia regulates tumor metastasis by modulation of the TGF-beta pathway. Cancer Res. 73:1800–1810. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia T, Levy L, Levillayer F, Jia B, Li G, Neuveut C, Buendia MA, Lan K, Wei Y. 2013. The four and a half LIM-only protein 2 (FHL2) activates transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling by regulating ubiquitination of the E3 ligase Arkadia. J. Biol. Chem. 288:1785–1794. 10.1074/jbc.M112.439760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakli M, Karvonen U, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. 2005. SUMO-1 promotes association of SNURF (RNF4) with PML nuclear bodies. Exp. Cell Res. 304:224–233. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang SH, Sharrocks AD. 2010. The SUMO E3 ligase activity of Pc2 is coordinated through a SUMO interaction motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:2193–2205. 10.1128/MCB.01510-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satijn DP, Olson DJ, van der Vlag J, Hamer KM, Lambrechts C, Masselink H, Gunster MJ, Sewalt RG, van Driel R, Otte AP. 1997. Interference with the expression of a novel human polycomb protein, hPc2, results in cellular transformation and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6076–6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. 2011. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300:C723–C742. 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eitner K, Koch U, Gaweda T, Marciniak J. 2010. Statistical distribution of amino acid sequences: a proof of Darwinian evolution. Bioinformatics 26:2933–2935. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salichs E, Ledda A, Mularoni L, Alba MM, de la Luna S. 2009. Genome-wide analysis of histidine repeats reveals their role in the localization of human proteins to the nuclear speckles compartment. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000397. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill G. 2005. Something about SUMO inhibits transcription. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15:536–541. 10.1016/j.gde.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang X, Qi Y, Zuo Y, Wang Q, Zou Y, Schwartz RJ, Cheng J, Yeh ET. 2010. SUMO-specific protease 2 is essential for suppression of polycomb group protein-mediated gene silencing during embryonic development. Mol. Cell 38:191–201. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu XV, Rodrigues TM, Tao H, Baker RK, Miraglia L, Orth AP, Lyons GE, Schultz PG, Wu X. 2010. Identification of RING finger protein 4 (RNF4) as a modulator of DNA demethylation through a functional genomics screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15087–15092. 10.1073/pnas.1009025107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. 1999. Methylation-induced repression—belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell 99:451–454. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81532-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu B, Tahk S, Yee KM, Fan G, Shuai K. 2010. The ligase PIAS1 restricts natural regulatory T cell differentiation by epigenetic repression. Science 330:521–525. 10.1126/science.1193787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massague J, Gomis RR. 2006. The logic of TGFbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. 580:2811–2820. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith JP, Solomon TE. 2014. Cholecystokinin and pancreatic cancer: the chicken or the egg? Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 306:G91–G101. 10.1152/ajpgi.00301.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, Gnirke A, Jaenisch R, Lander ES. 2008. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 454:766–770. 10.1038/nature07107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. 2008. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat. Genet. 40:499–507. 10.1038/ng.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plasari G, Calabrese A, Dusserre Y, Gronostajski RM, McNair A, Michalik L, Mermod N. 2009. Nuclear factor I-C links platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor beta1 signaling to skin wound healing progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:6006–6017. 10.1128/MCB.01921-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee KY, Jeong JW, Wang J, Ma L, Martin JF, Tsai SY, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. 2007. Bmp2 is critical for the murine uterine decidual response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:5468–5478. 10.1128/MCB.00342-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Croce L, Helin K. 2013. Transcriptional regulation by Polycomb group proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20:1147–1155. 10.1038/nsmb.2669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanzuolo C, Orlando V. 2012. Memories from the polycomb group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46:561–589. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon JA, Kingston RE. 2013. Occupying chromatin: polycomb mechanisms for getting to genomic targets, stopping transcriptional traffic, and staying put. Mol. Cell 49:808–824. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pirrotta V, Li HB. 2012. A view of nuclear Polycomb bodies. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22:101–109. 10.1016/j.gde.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klose RJ, Bird AP. 2006. Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:89–97. 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deaton AM, Bird A. 2011. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 25:1010–1022. 10.1101/gad.2037511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ku M, Koche RP, Rheinbay E, Mendenhall EM, Endoh M, Mikkelsen TS, Presser A, Nusbaum C, Xie X, Chi AS, Adli M, Kasif S, Ptaszek LM, Cowan CA, Lander ES, Koseki H, Bernstein BE. 2008. Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000242. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartke T, Vermeulen M, Xhemalce B, Robson SC, Mann M, Kouzarides T. 2010. Nucleosome-interacting proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation. Cell 143:470–484. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Farcas AM, Blackledge NP, Sudbery I, Long HK, McGouran JF, Rose NR, Lee S, Sims D, Cerase A, Sheahan TW, Koseki H, Brockdorff N, Ponting CP, Kessler BM, Klose RJ. 2012. KDM2B links the Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) to recognition of CpG islands. Elife 1:e00205. 10.7554/eLife.00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu X, Johansen JV, Helin K. 2013. Fbxl10/Kdm2b recruits polycomb repressive complex 1 to CpG islands and regulates H2A ubiquitylation. Mol. Cell 49:1134–1146. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PA, Rappsilber J, Helin K. 2011. TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature 473:343–348. 10.1038/nature10066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]