Abstract

Chlamydiae are widespread Gram-negative pathogens of humans and animals. Salicylidene acylhydrazides, developed as inhibitors of type III secretion system (T3SS) in Yersinia spp., have an inhibitory effect on chlamydial infection. However, these inhibitors also have the capacity to chelate iron, and it is possible that their antichlamydial effects are caused by iron starvation. Therefore, we have explored the modification of salicylidene acylhydrazides with the goal to uncouple the antichlamydial effect from iron starvation. We discovered that benzylidene acylhydrazides, which cannot chelate iron, inhibit chlamydial growth. Biochemical and genetic analyses suggest that the derivative compounds inhibit chlamydiae through a T3SS-independent mechanism. Four single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified in a Chlamydia muridarum variant resistant to benzylidene acylhydrazides, but it may be necessary to segregate the mutations to differentiate their roles in the resistance phenotype. Benzylidene acylhydrazides are well tolerated by host cells and probiotic vaginal Lactobacillus species and are therefore of potential therapeutic value.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydiae are a group of Gram-negative bacteria that require eukaryotic cells as hosts for replication (1). Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia trachomatis are important human pathogens. C. pneumoniae is an etiologic agent of pneumonia and bronchitis and a potential cofactor for atherosclerosis (2) and late-onset Alzheimer disease (3, 4). C. trachomatis is the most prevalent sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen (5, 6). Repeated urogenital chlamydial infections may lead to devastating complications, including ectopic pregnancy, abortion, tubal factor infertility, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Among the non-human-pathogenic chlamydiae, Chlamydia muridarum is a particularly useful organism due to its ability to model human chlamydial infections in mice (7–9). In addition, several C. trachomatis serotypes cause conjunctivitis and are the most common infectious agents associated with blindness in some developing countries (10, 11).

Chlamydiae share a biphasic developmental cycle consisting of two alternating cellular forms—the infectious but nondividing elementary body (EB) and the proliferative but noninfectious reticulate body (RB). Chlamydial infection is initiated with the binding of an EB to the host cell and the formation of an EB-containing vacuole, termed an inclusion. Inside the inclusion, the EB differentiates into an RB, which replicates by binary fission. Around the midpoint of the developmental cycle, RBs progressively reorganize back to EBs, which are then released from the host cell at the end of the developmental cycle (12, 13).

Chlamydiae encode a type III secretion system (T3SS) (14), a needle-like structure found in many Gram-negative pathogens. As a virulence factor, T3SS manipulates host cell function by translocating proteins with signaling activities from the bacterial cytoplasm into the host cell (15–18). Thus, inhibition of T3SS is an attractive therapeutic strategy for infectious diseases (19, 20). Indeed, treatment of Yersinia with salicylidene acylhydrazides, inhibitors of T3SS, reduces the secretion of bacterial virulence proteins (20, 21).

Salicylidene acylhydrazides also inhibit the secretion of certain proteins from chlamydiae (22–24). In addition, these compounds inhibit chlamydial growth (22, 23, 25, 26). Nevertheless, it was not certain if these compounds exert their antichlamydial effect through direct inhibition of the chlamydial T3SS since the effect can be reversed with iron (26). This uncertainty was further augmented by the observation that salicylidene acylhydrazides also inhibit the growth of human immunodeficiency virus 1 in an iron-dependent manner (27). Therefore, we wanted to investigate whether or not it would be possible to segregate the antichlamydial effect, T3SS inhibition, and iron chelation by modifying salicylidene acylhydrazides. Here, we report that benzylidene acylhydrazides, derived by relocation of the hydroxyl group required for iron chelation, have T3SS-independent antichlamydial effects. Significantly, the antichlamydial effects of the derivatives are not affected by the addition of iron, and they are better tolerated by host cells than salicylidene acylhydrazides. Thus, benzylidene acylhydrazides constitute a new class of antichlamydials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

Synthesis of INP0007 [N′-(3,5,-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)-4-nitrobenzohydrazide] has been reported previously (21, 28). CF0001 [N′-(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-3-nitrobenzohydrazide] and CF0002 [N′-(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-4-nitrobenzohydrazide] were prepared according to published procedures (29). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker DRX-400 spectrometer at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively. NMR experiments were conducted at 298 K in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) (residual solvent peaks, 2.50 ppm [δH] and 39.52 ppm [δC]). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was carried out with a Waters LC system equipped with an Xterra C18 column (50 by 19 mm, 5 μm, 125 Å), eluted with a linear gradient of CH3CN in water, both of which contained formic acid (0.2%). A flow rate of 1.5 ml/min was used, and detection was performed at 214 nm. Mass spectra were obtained on a Water micromass ZQ 2000 using positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI). All target compounds were ≥95% pure according to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) UV traces. CF0001, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 12.25 (s, 1H), 10.50 (bs, 1H), 8.74 (t, J = 2.07 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (dd, J = 2.57, 8.20 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (dt, J = 1.30, 7.70 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.94 (s, 2H), 7.84 (t, J = 7.99 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz): δ 161.04, 152.42, 147.76, 145.77, 134.65, 134.18, 130.80 130.32, 128.60, 126.41, 122.34, 112.23. ESI-MS m/z calculated for C14H26N4O9 (M-H)+ 439.89; found 439.81. CF0002, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 12.22 (s, 1H), 10.50 (bs, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 8.56 Hz, 2H), 8.32 (s, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 8.71 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz): δ 161.54, 152.43, 149.29, 145.87, 138.95, 130.81, 129.21, 128.59, 123.65, 112.23. ESI-MS m/z calculated for C14H26N4O9 (M-H)+ 439.89; found 439.84.

Chlamydial strains, host cells, and culture conditions.

HeLa cells were used for all cell culture experiments, except for C. trachomatis serovar A recoverable inclusion-forming unit (IFU) assays, which were performed with McCoy cells. Both HeLa cells and McCoy cells were maintained as adherent cultures using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and gentamicin (final concentrations, 10% [vol/vol] and 20 μg/ml, respectively). For inhibition tests and selection of CF0001-resistant mutants, HeLa cells were about 50 to 70% confluent at the time of inoculation if the culture was to be treated with the inhibitor. For blind passaging without CF0001 treatment during mutant selection, cells were nearly confluent at the time of inoculation, and cycloheximide was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. For expansion and titration of EB stock, cells were also nearly confluent and cycloheximide was included.

Wild-type C. muridarum (strain Nigg II, traditionally known as mouse pneumonitis pathogen [MoPn]), wild-type C. pneumoniae (strain AR39) and C. trachomatis serovar L2 (strain 434/Bu) were purchased from ATCC. Wild-type C. trachomatis serovar D (UW-3/CX) and the isogenic mutants designated D-EC and D-LC have been described previously (30). Wild-type C. trachomatis serovar A (strain HAR-13) (31) was kindly provided by Guangming Zhong (University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio). Selection of MCR, an MoPn variant resistant to CF0001, was initiated by inoculating a T75 flask with 107 inclusion-forming units (IFU) of MoPn EB and culture in medium containing 100 μM CF0001 for 48 h. With this multiplicity of infection (MOI) (about 3 IFU/cell), small inclusions were occasionally observed, even though 100 μM CF0001 was able to completely prevent inclusion formation at an MOI of 0.2. Half of the harvest was inoculated onto HeLa cells in another T75 flask, which was cultured again with medium containing 100 μM CF0001. No inclusions were visible at the end of this second passage in the presence of the inhibitor (48 h after inoculation). The culture was harvested, and 100% of the harvest was inoculated onto another T75 flask, which was cultured in the medium supplemented with 1 μg/ml cycloheximide but no CF0001. In the absence of any visible inclusions under the microscope, the culture was harvested and “blind passaging” was repeated three additional times without CF0001 treatment. A few inclusions were sporadically observed (less than one inclusion per field) in the fourth blind passage, which was harvested and passed into a new flask of HeLa cells. CF0001 treatment and blind passaging were repeated as guided by the apparent detection (or not) of inclusions in the cultures. After a total of 15 passages with 100 or 110 μM CF0001 and 21 inhibitor-free passages, inclusions persisted in three consecutive passages in the presence of 100 μM CF0001, which indicated emergence of CF0001 resistance. The mutant, designated MCR, was further cultured with medium containing 120, 130, 140, 150, and 160 μM CF0001 for 10, 4, 1, 1, and 1 passage, respectively. The mutant harvested from the passage with 160 μM CF0001 was expanded in the absence of the inhibitor. EBs were purified with ultracentrifugation in RenoCal gradients, and aliquots were frozen at −80°C (32).

Analysis of Yersinia T3S.

The effects of CF0001, CF0002, and INP0007 on the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III secretion (T3S) strain (YPIII) were determined using a previously described luciferase reporter gene assay for Yersinia outer protein E (YopE) secretion (20, 21). Briefly, an overnight culture of YPIII(pIB102) yopE-luxAB cells was diluted into calcium-depleted brain heart infusion (BHI) (5 mM EGTA, 20 mM MgCl2) in a white 96-well plate with CF0001, CF0002, and INP0007 at 25 to 150 μM or 1% DMSO. After 1 h of shaking incubation at 26°C, type III secretion (T3S) was induced by raising the temperature to 37°C for 2 h on a rotary shaker. Luminescence was measured in a microtiter plate reader after addition of decanal. Inhibition of Yop secretion was confirmed in the wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis strain YPIII(pIB102). Briefly, bacteria were grown at 26°C for 30 min with 100 μM compound or solvent (1% DMSO) in BHI containing 0 or 2.5 mM CaCl2 and then shifted to 37°C for 3 h of continued incubation. Secreted proteins in the culture supernatants were concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, visualized by Coomassie blue staining, and identified by their sizes (20, 21).

Determination of tolerance by Lactobacillus.

Lactobacillus crispatus strain ATCC 33820, Lactobacillus gasseri strain ATCC 33323, and Lactobacillus jensenii strain ATCC 25258 were cultured with Lactobacilli MRS broth (Difco) in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator (33). To test the effects of benzylidene acylhydrazides on lactobacilli, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 with fresh MRS broth containing CF0001, CF0002, or the vehicle DMSO. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured on an Amersham spectrophotometer. When necessary, cultures were diluted with MRS until the reading fell below 0.7, where the OD600 remained linear for the bacterial concentration.

Chlamydia inhibition tests.

Conditions for the evaluation of inhibition by small compounds have been previously described (33, 34). At the time of inoculation, cells were about 60 to 70% confluent. The MOI was 0.2. Centrifugation (545 × g for 30 min at room temperature) was used to facilitate infection of the C. trachomatis A and D strains. Chemical treatment was initiated by replacement with medium containing the indicated concentrations of an inhibitor or the vehicle DMSO (final concentration, 1%) 1.5 to 2 h postinoculation. Twenty-four hours (MoPn and MCR), 30 h (C. trachomatis D strains), or 40 h (C. trachomatis A and C. pneumoniae) after inoculation, cultures were terminated by methanol fixation and/or scraping. Methanol-fixed cells were subjected to sequential reactions with a primary antibody and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (33, 34). Either Evans blue or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) was used as a counterstain.

The scraped-off cells were disrupted by brief sonication to release C. muridarum, C. trachomatis A, and C. pneumoniae or by vortexing the cell suspension after the addition of 4 glass beads to release C. trachomatis D. Recoverable IFU were quantified by inoculating secondary cultures with 1:10 serially diluted lysates and immunostaining. The primary antibodies used for immunostaining were monoclonal mouse anti-major outer membrane protein (anti-MOMP) clone MC22 (for detection of C. muridarum), monoclonal antilipopolysaccharide (anti-LPS) clone EVIH1 (for detection of C. trachomatis D), polyclonal mouse anti-MoPn EBs (for detection of C. trachomatis A and C. muridarum), and polyclonal rabbit anti-AR39 (for detection of C. pneumoniae).

Determination of host cell tolerance.

HeLa cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 104 cells/well. After overnight growth, cells were switched into culture medium containing INP0007 or CF0001. Forty-eight hours later, cells were enumerated after they were detached from the plastic by trypsinization.

DNA sequencing analyses.

Sequences of selected regions in the genome were determined using the automated fluorochrome-conjugated dideoxynucleotide termination sequencing technique, a Sanger sequencing method (33). The genome of MCR was sequenced on the Solexa platform as we have described previously (34).

Preparation of RNA and genomic DNA for quantitative analyses.

HeLa cells were inoculated with purified EBs of MoPn or MCR at an MOI of 0.2. Two hours later, free EBs were removed by washes. Infected cells were harvested using the TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) by following the manufacturer's instructions. The harvest was centrifuged at 2,000 × g. Genomic DNA was extracted from the interphase and organic phase; total RNA was extracted from the aqueous phase. RNA samples were subjected to 2 cycles of RNase-free DNase treatment. Reverse transcription was performed as previously described (34).

qPCR.

Quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) using either cDNA or genomic DNA as the template were performed as previously described (34).

Preparation of GrgA.

The open reading frame (ORF) of C. muridarum GrgA (TC0791) and its mutated version carrying an R51G substitution found in MCR were cloned into pET28a between the NdeI and XhoI sites. Expression of the N-terminally His6-tagged proteins were carried out as previously described (35). Recombinant proteins were purified from guanidine hydrochloride-denatured Escherichia coli extract using metal TALON affinity resin (Clontech) and renatured through stepwise dialysis (35). Purified proteins were stored at −80°C prior to use.

In vitro transcription assay.

The transcription activation activities of recombinant GrgA and R51G GrgA were determined using the in vitro transcription reporter plasmid pMT1125-Z100, in which a defA promoter leads a guanine-less cassette, chlamydial RNA polymerase partially purified from C. trachomatis L2, and indicated concentrations of either GrgA or R51G GrgA (35). Reactions were initiated by the addition of α-[32P]CTP, ATP, UTP and 3′-O-methyl-GTP and were terminated 10 min later by adding 70 μl of 2.86 M ammonium acetate containing 4 mg of glycogen and placing the tubes onto ice. Transcribed RNA was precipitated with ethanol, resolved with urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, visualized, and quantified using a Typhoon PhosphorImager (35). For experiments determining the effects of CF0001 and CF0002, the compounds were first mixed with GrgA or R51G GrgA before the addition of the RNA polymerase (RNAP) and plasmid DNA template. The mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min prior to the initiation of the reaction.

ATP import assay.

ATP uptake by E. coli ATM1173, which expresses His-tagged ATP/ADP translocase (CTL0321), was determined as previously reported (36) with modifications. In preliminary experiments, ATM1172, which carries the empty pET19 plasmid, failed to practically take up radioactivity (data not shown), which is consistent with the findings of Fisher et al. (36). Therefore, ATM1172 was not included in later experiments. Briefly, bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C on a shaker. For the ATP import assay, overnight bacterial cultures were diluted 50-fold with fresh LB broth containing 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), which activates the T7 polymerase-controlled expression system. When cultures reached an OD of ∼0.6, bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g and washed twice with the M9 minimal medium prechilled on ice. Bacteria were resuspended in M9 medium. Each assay mixture, in a total volume of 100 μl of M9 medium, contained 108 bacteria and 50 nM (800 Ci/mmol) [α-32P]ATP (MP Biomedicals) with or without CF0001, CF0002, or NAD. Reactions were initiated by transferring the tubes to a 37°C water bath and were terminated 10 min later by placing the tubes onto ice. Extracellular ATP was removed by filtration through 0.2-μm-pore polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and the amounts of radiolabeled ATP transported into the cells were quantified by scintillation counting of bacteria retained on the filters.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete genome sequence of MCR has been deposited into the NCBI genome database under accession no. CP007276.

RESULTS

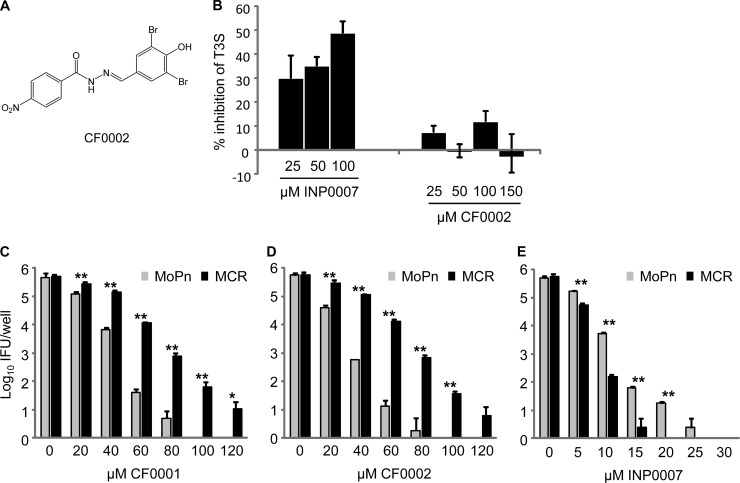

Loss of T3SS inhibition following conversion of INP007 into CF0001.

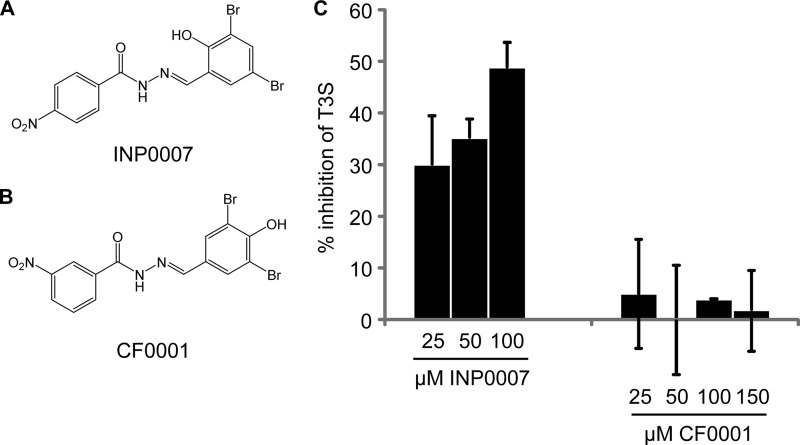

INP0007 (Fig. 1A) and other salicylidene acylhydrazides are inhibitors of T3SS. We found that relocation of the hydroxy and nitro groups in INP0007 to give CF0001 (Fig. 1B) resulted in loss of T3SS inhibition in Y. pseudotuberculosis. Accordingly, INP0007, in the range of 25 to 100 μM, demonstrated progressive inhibition of T3S; in contrast, CF0001 showed no dose-dependent effect at concentrations up to 150 μM (Fig. 1C). Data for INP0007 at 150 μM could not be obtained due to compound precipitation. Coomassie blue staining of secreted proteins resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (20, 21) confirmed the lack of inhibition of Yop secretion by 100 μM CF0001 in the wild-type Y. pseudotuberculosis strain YPIII(pIB102) (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Loss of T3S inhibition as a result of conversion of INP0007 into CF0001. (A and B) Structures of INP0007 (A) and CF0001 (B). (C) T3S inhibition by INP0007 but not CF0001. Y. pseudotuberculosis YPIII(pIB102) yopE-luxAB was incubated at 26°C in calcium-depleted medium with the indicated additive. Secretion was induced by raising the temperature to 37°C, and luminescence was measured. Data are presented as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control in mean and standard deviation from triplicate determinations.

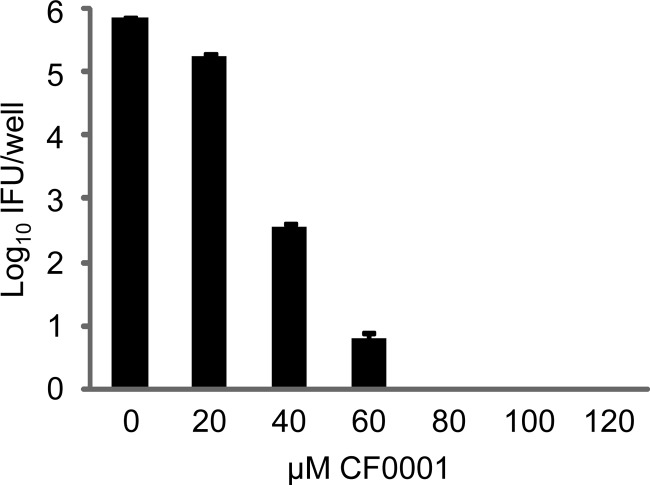

Antichlamydial activity of CF0001.

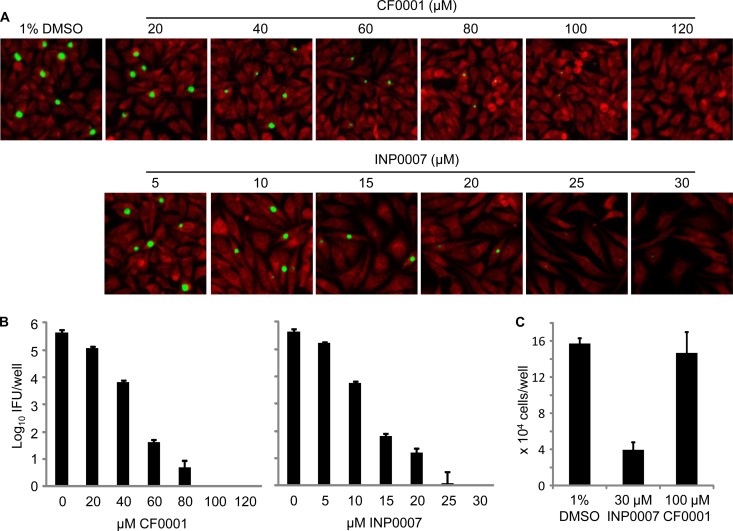

Both CF0001 and INP0007 inhibited C. muridarum (MoPn) in a dose-dependent manner, as demonstrated by direct staining of inclusions that formed on HeLa cell monolayers. Accordingly, reductions of both inclusion size and number were observed starting with 20 μM CF0001 (Fig. 2A, upper panel) and 10 μM INP0007 (Fig. 2A, lower panel). The inhibitory effects of CF0001 and INP0007 on MoPn infection were also demonstrated by determining the number of infectious EBs formed with different concentrations of the compounds (Fig. 2B). CF0001 also inhibited the growth of C. trachomatis L2 (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Inhibition of MoPn growth by CF0001 and INP0007 and apparent lack of toxicity to host cells in CF0001. HeLa cells were infected with MoPn EBs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2. Treatment started 2 h postinoculation. Twenty-four hours postinoculation, cells were either fixed for an immunofluorescence assay (A) or lysed for the determination of recoverable IFU (B). In panel A, chlamydiae were stained with a polyclonal anti-EB antibody (green) and cells were counterstained with Evans blue (red). In panel B, cultures with 0 μM CF0001 or INP0007 were treated with 1% DMSO, the solvent for CF0001 and INP0007. (C) Uninfected HeLa cells at 20% confluence were cultured with medium containing indicated compounds and were enumerated 48 h later.

Better tolerance of CF0001, compared to INP0007, by host cells was apparent in infected cultures by 24 h (Fig. 2A). The differential cytotoxic effects were further demonstrated by treatment of uninfected cells with either 100 μM CF0001 or 30 μM INP0007, which had comparable inhibition efficiencies, starting around 20% cell confluence. Forty-eight hours later, there were about 4-fold more cells in wells treated with DMSO or CF0001 than in wells treated with INF0007 (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these findings suggest that CF0001 is an antichlamydial compound that is well tolerated by HeLa cells.

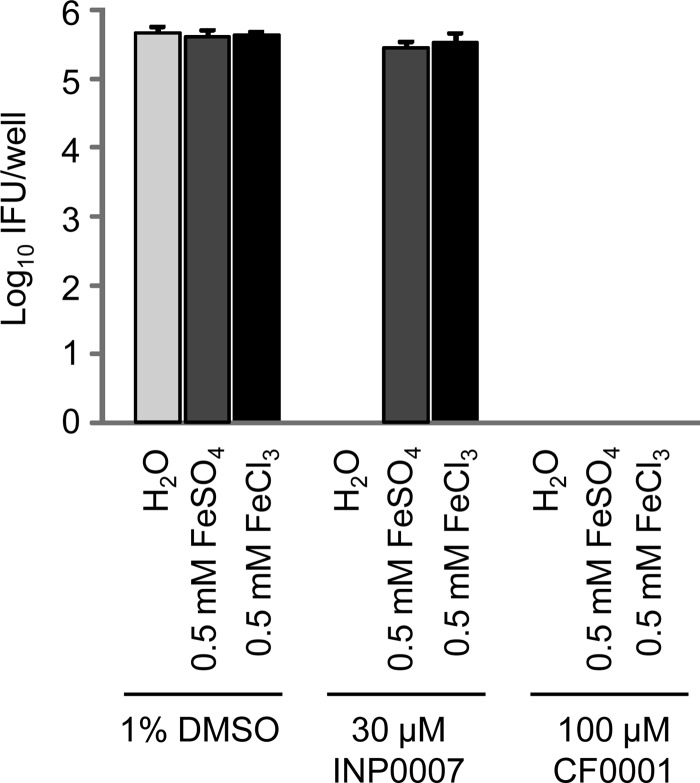

Reversal of antichlamydial activity of INP0007 but not of CF0001 by iron.

The inhibition of chlamydial infection by some salicylidene acylhydrazides can be reversed with iron (26). Consistent with this, either 0.5 mM FeSO4 or 0.5 mM FeCl3 restored chlamydial growth in the presence of 30 μM INP0007. In CF0001, the hydroxyl group in INP0007 that participates in iron chelation is shifted to a position that does not allow formation of the metal chelate. Thus, neither FeSO4 nor FeCl3 could reverse the antichlamydial activity of CF0001 (Fig. 3). These results suggest that INP0007 and CF0001 inhibit chlamydiae through different mechanisms.

FIG 3.

Reversal of INP0007- but not CF0001-mediated chlamydial growth inhibition by iron. Infection and treatment were performed similarly to those in Fig. 2B.

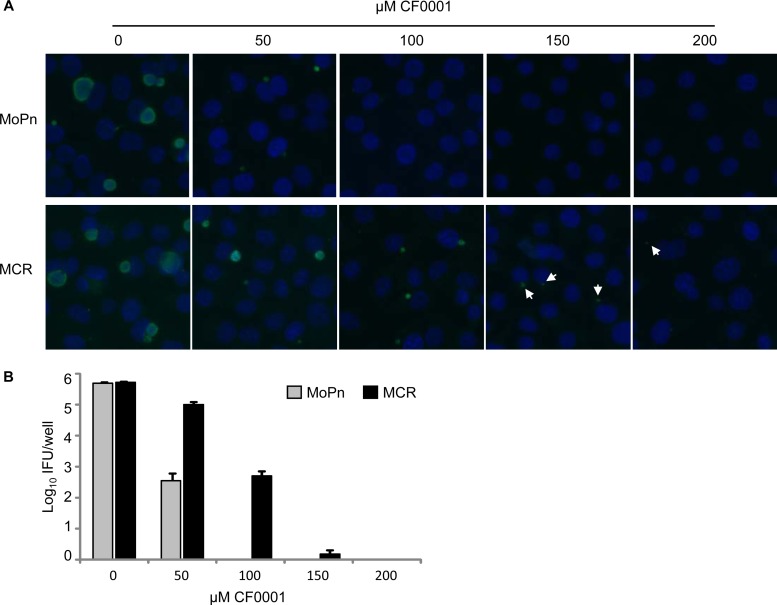

Selection of CF0001-resistant chlamydial mutants.

To determine the molecular targets of CF0001, we set out to select for CF0001-resistant mutants. A lengthy selection process that lasted 3 months led to the isolation of a mutant, designated MCR (MoPn with CF0001 resistance). CF0001 resistance in MCR was demonstrated by increased abilities to form more and larger inclusions (Fig. 4A) and to produce increased numbers of EBs (Fig. 4B) in the presence of the inhibitor. This resistance was stable after 6 passages, which is estimated to be more than 30 generations based on 5 to 7 doubling cycles per passage, using medium free of the inhibitor (data not shown). Procedures performed in parallel starting with 5 × 107 IFUs failed to isolate a resistant mutant from C. trachomatis L2.

FIG 4.

CF0001 resistance in MoPn mutant MCR. (A) Increased capacity to form inclusions in the presence of CF0001 as shown by MOMP immunostaining. (B) Increased EB production in the presence of CF0001 as determined by quantifying recoverable EBs from CF0001-treated cultures. Infection and treatment were carried out as described in Fig. 2, with the exception that cells were counterstained with the DNA dye DAPI in panel A.

Cross-resistance to CF0002 but not to INP0007 in MCR.

We next synthesized CF0002 and determined its effect on the growth of wild-type MoPn and MCR. CF0002 (Fig. 5A) has an identical structure to CF0001 (Fig. 1B), except the NO2 group is in the same position as in INP0007 (Fig. 1A). Similar to CF0001 (Fig. 1C), CF0002 failed to inhibit T3S in Yersinia, as demonstrated by the luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 5B) and staining of secreted proteins (data not shown). While growth of the parental MoPn was inhibited by CF0002 at a comparable efficiency to CF0001; MCR displayed increased tolerance to CF0002 (Fig. 5C and D). These results suggest that the benzylidene acylhydrazides CF0001 and CF0002 inhibit chlamydiae through the same mechanism.

FIG 5.

Cross-resistance to CF0002, an analog of CF0001, but not the T3SS inhibitor INP0007 in MCR. (A) Structure of CF0002. (B) Lack of T3S inhibition in Yersinia by CF0002. T3S was determined as in Fig. 1C. (C) Resistance to CF0001 and CF0002 in MCR (panels C and D, respectively). (E) Increased sensitivity to INP0007 in MCR. (C to E) Infection and treatment were carried out as in Fig. 2B. * and **, statistically significant differences between MoPn and MCR (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, two-tailed Student's t test).

We also compared the inhibition efficacies of INP0007 in wild-type MoPn and MCR. MCR did not show any cross-resistance to INP0007. In fact, MCR was even more susceptible to INP0007 than the parental organism (Fig. 5E). These results further support the notion that CF0001 and CF0002 exert their antichlamydial effects through a mechanism that is distinct from the one that INP0007 utilizes.

Identification of four point mutations in the MCR genome.

To identify potential target(s) of CF0001 and CF0002, we sequenced the entire genome of MCR using the Solexa single-molecule sequencing technology (34). A total of 9,951,355 Solexa reads of 31 bp were mapped onto the MoPn reference genome (37). This represents a >50× average depth and 99.976% coverage of the 1,073-kb reference genome and 100% coverage of the 7,501-bp MoPn plasmid and leaves 12 short gaps of 262 bp in total. The gaps were filled by Sanger sequencing.

Solexa sequencing identified 8 insertion/deletion sites (indels) in the genome of MCR. Sanger sequencing confirmed that all of these 8 indels were also present in the parental strain. Solexa also identified 31 potential single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the genome of MCR. Nineteen of the 31 SNPs were reported because of the nucleotide ambiguity in the reference genome (37). Sanger sequencing confirmed that the parental strain had the same nucleotides as in the MCR at all 19 sites (data not shown) and found that only 4 of the 12 remaining SNPs identified by Solexa represented specific changes found only in MCR, whereas the other 8 SNPs were present in both MCR and the parental strain (data not shown). For description convenience, the 4 MCR-specific SNPs are named SNP1 to -4 according to their locations in the genome (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mutations identified in MCR

| SNP no. | Positiona | ORF | Description | Nucleotide in: |

Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental strain | MCR | |||||

| 1 | 59134 | TC0052 | Major outer membrane protein (ompA) | G | A | A228V |

| 2 | 399603 | TC0335-TC0336 | Intergenic ADP/ATP translocase-hypothetical protein | C | G | Reduced TC0335 |

| 3 | 472827 | TC0412 | Virulence factor | T | G | L24→stop |

| 4 | 935223 | TC0791 | General regulator of gene A (grgA) | G | C | R51G |

The numbers shown are positions of SNPs in the genome (GenBank accession no. NC_002620).

Inhibition of C. pneumoniae bearing the MOMP mutation of MCR by CF0001.

SNP1 causes an A228V mutation in the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) (Table 1). According to a structural model, A228 is predicted to be in a conserved β-sheet located in the lipid bilayer (38). Since MOMP may function as a porin (39–41), it is plausible that it mediates the entry of CF0001 and CF0002, and an intramembrane domain mutation in it may change the property of the pore, leading to decreased entry. A228 is conserved among all sequenced strains of C. muridarum, C. trachomatis, and C. felis but is substituted for by valine in C. pneumoniae, similar to MCR. If the A228V substitution is responsible for the resistance phenotype in MCR, C. pneumoniae would also be resistant to the inhibitors, assuming that other amino acid changes in the protein do not affect inhibition efficacy. However, CF0001 effectively inhibited C. pneumoniae AR39 (Fig. 6). From the comparison of the inhibition data for AR39 (Fig. 6) with data for the parental MoPn strain (Fig. 2B, left), it appears that the human respiratory pathogen may be even slightly more susceptible to the inhibitor than the murine pathogen (Fig. 2 and 6).

FIG 6.

Inhibition of C. pneumoniae AR39, which carries an Ala→Val mutation in a transmembrane domain of MOMP due to SNP1, by CF0001. HeLa cells were infected with AR39 EBs at an MOI of 0.2. Treatment started 2 h after inoculation. At 42 h, cells were lysed for the determination of recoverable IFU. Cultures with 0 μM CF0001 were treated with 1% DMSO.

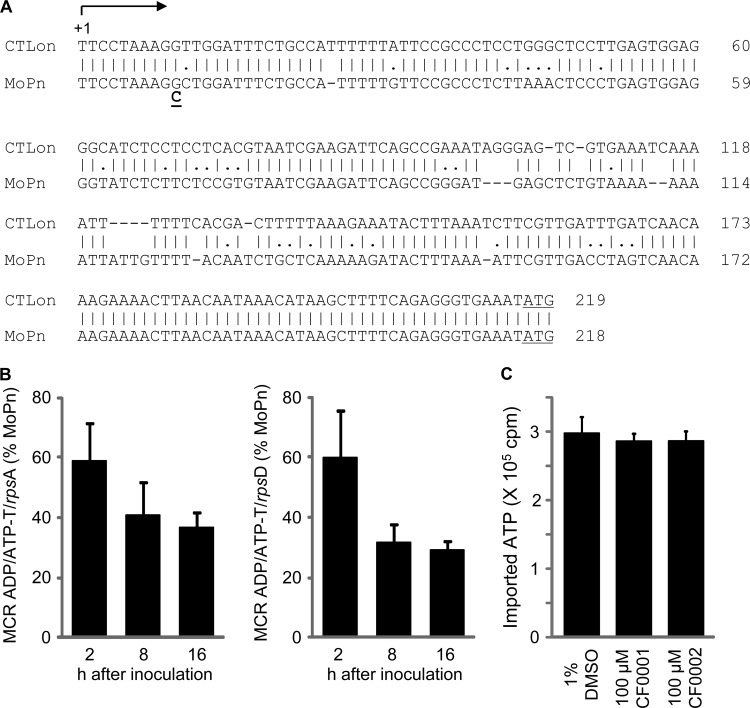

Decreased expression of the ATP/ADP translocase gene with SNP2 in MCR.

SNP2 was located in a noncoding region between the TC0335 and TC0336 genes, which code for an ATP/ADP translocase (42) and a hypothetical protein, respectively. A previous study has identified the transcription start site of gene CTLon_0316 in the C. trachomatis L2c strain (43). CTLon_0316 is a homolog of TC0335. Sequence alignment indicates that CTLon0316 and TC0335, both coded for by the lower strand, share the same transcription start site and that SNP2 changes the 10th nucleotide in the TC0335 mRNA (Fig. 7A). In addition, there is a strong Rho-independent transcription termination signal 47 bp downstream of the translational stop codon of TC0336 and 61 bp upstream of the predicted transcription start site of TC0335 (sequence not shown), which codes for an ATP/ADP translocase (42). These findings suggest that SNP2 is unlikely to affect the expression of TC0336.

FIG 7.

Decreased expression of the ADP/ATP translocase gene with SNP2 in its 5′ untranscribed region (UTR) in MCR and lack of an effect of CF0001 and CF0002 on the translocase-mediated ATP uptake in E. coli. (A) Alignment of the 5′ UTR of the ADP/ATP translocase gene (TC0335) in C. trachomatis L2 to that of MoPn. +1 denotes the transcription initiation site, identified by Albrecht et al. (43) for C. trachomatis L2. In MRC, G at putative position 10 was replaced with C. Note that SNP2 is shown as C→G mutation in Table 1 because TC0335 is encoded by the bottom strand of the genome. In both species, the ATG initiation codon is included to mark the end of the 5′ UTRs. (B) Decreased ADP/ATP translocase mRNA levels in MCR. HeLa cells were infected with either MoPn or MCR at an MOI of 0.2 and harvested at the indicated times. mRNAs of the translocase and ribosomal genes rpsA and rpsD were determined by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (C) ATP import by C. trachomatis ATP/ADP translocase is not affected by CF0001 or CF0002. The ability of the translocase to mediate the uptake of [α-32P]ATP was determined in E. coli ATM1173, which expresses His-tagged ATP/ADP translocase (CTL0321), as detailed in Materials and Methods. CF0001 and CF0002 were preincubated with E. coli prior to the initiation of assays.

To test if SNP2 affects expression of the translocase, we used qPCR to quantify its mRNA and control transcripts of rpsA and rpsD (44) at multiple points (2, 8, and 16 h) in the developmental cycle. We detected consistent decreases in the translocase expression (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that CF0001 and CF0002 do not directly target the translocase per se; however, decreased expression of the translocase may lead to resistance if the translocase mediated the entry of the inhibitors.

To test the latter possibility, we determined the effects of CF0001 and CF0002 on the ability of E. coli ATM1173, which expresses the translocase, to import ATP. As expected, NAD, which is transported into chlamydiae through the same translocase (36), inhibited the uptake of [α-32P]ATP in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown). In contrast, neither CF0001 nor CF0002 demonstrated any effect on ATP import in these bacteria (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the ATP/ADP translocase does not mediate the entry of benzylidene acylhydrazides.

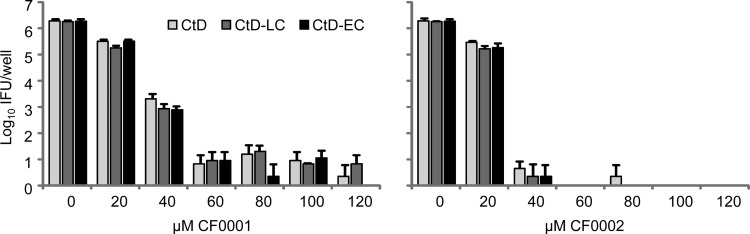

Inhibition of Chlamydia by CF0001 and CF0002 is not affected by mutations in the gene coding for the virulence factor CT135.

SNP3 caused translation termination at codon 24 in TC0412, homolog of the C. trachomatis virulence factor CT135 (30). The amino acid sequence of TC0412 is 96% identical to that of CT135, a 360-amino-acid virulence factor identified in the human pathogen C. trachomatis serovar D strain CtD using a murine infection model (30, 45). The effect of SNP3 on TC0412 protein expression resembles the effect of the single-nucleotide deletion in the late-clearance CtD mutant (LC-CtD) (30): whereas SNP3 converts the Leu-24 codon to a translation stop codon, a thymine deletion from CT135 in the LC-CtD mutant causes a frameshift at codon 45 (30). Therefore, we determined the effects of CF0001 and CF0002 on wild-type CtD and the isogenic mutants LC-CtD and EC-CtD (early clearance variant due to a frameshift at codon 182). As shown in Fig. 8, all three strains exhibited similar susceptibilities to the two compounds. These results suggest that the CT135 frameshift mutations in LC-CtD and EC-CtD do not affect the inhibition efficiency of the compounds.

FIG 8.

Similar susceptibilities of C. trachomatis D and isogenic mutants with frameshift mutations in the CT135 gene to CF0001 and CF0002. HeLa cells were infected with the indicated strains and treated with compounds starting 1.5 h postinoculation. Cultures were harvested at 26 h postinoculation for the determination of recoverable IFU. Cultures with 0 μM CF0001 or CF0002 were treated with 1% DMSO.

Transcription activation activity of GrgA is compromised by SNP4 but not inhibited by CF0001 or CF0002.

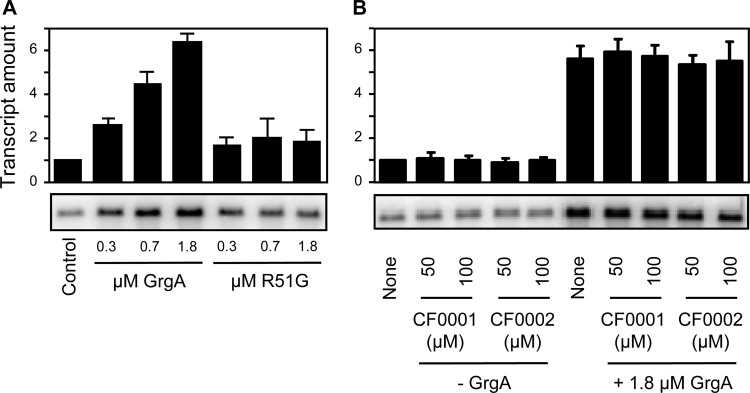

SNP4 caused a single-amino-acid substitution (R51G) in TC0791, a homolog of transcription activator GrgA recently identified in C. trachomatis L2 (35). TC0791 shares 80% sequence identity and 90% similarity to GrgA of C. trachomatis L2 (alignment not shown). Therefore, TC0791 is expected to function as a transcription activator as well. Indeed, His-tagged TC0791 demonstrated transcription activation activity in vitro (Fig. 9A). Interestingly, compared to the wild-type C. muridarum GrgA, the R51G GrgA found in MCR exhibits an apparent defect in transcription activation (Fig. 9A). Nonetheless, neither CF0001 nor CF0002 demonstrated any apparent effects on the transcription activation activity of wild-type GrgA (Fig. 9B). These data suggest that the compounds do not directly target GrgA.

FIG 9.

The R51G GrgA, as a consequence of SNP4, is defective in transcription activation (A), but CF0001 and CF0002 do not inhibit the transcription activation activity of GrgA (B). Transcription activity was determined by measuring the amount of guanineless transcript from a transcription reporter cassette placed downstream of a C. trachomatis PDF gene promoter (Z1 variant) (35).

The growth defect is an unlikely cause for resistance in MCR.

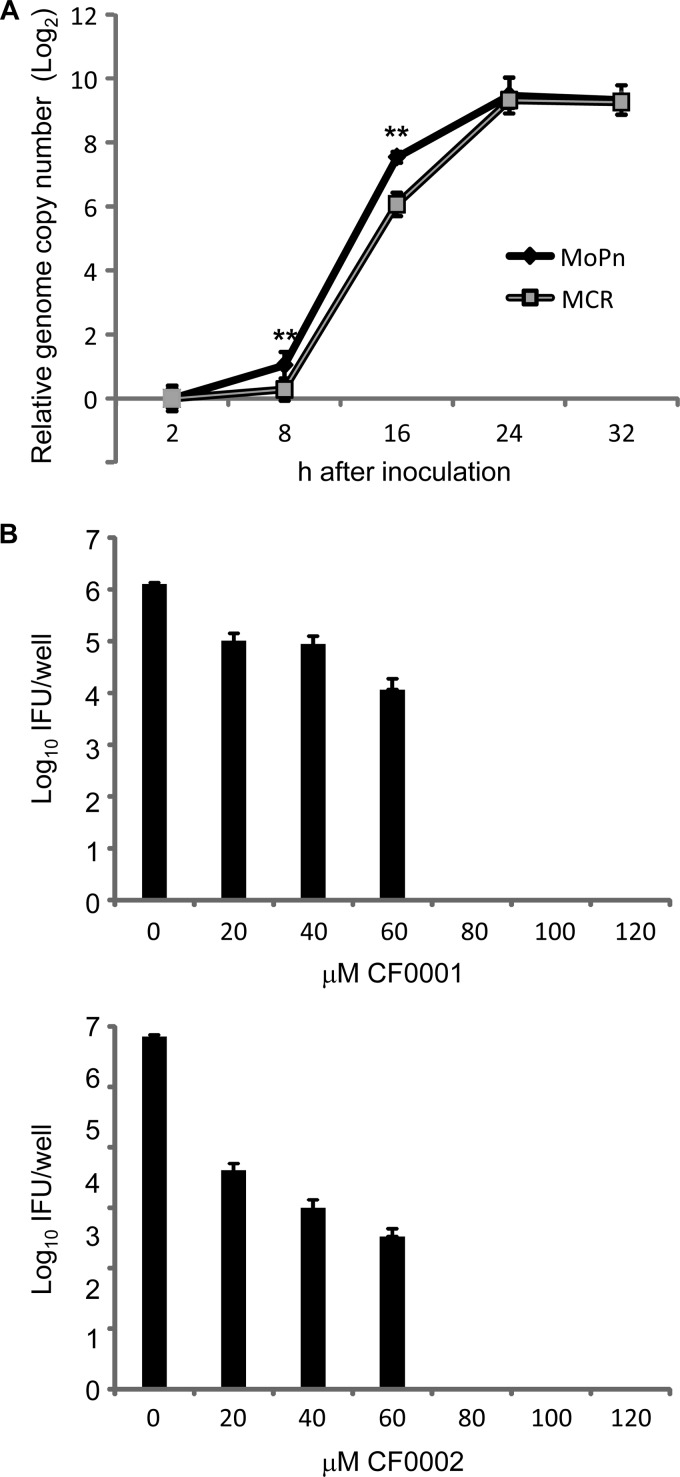

After being unable to identify any of the mutated genes as a clear target for benzylidene acylhydrazides, we investigated if MCR might have a lower growth rate and consequently displays phenotypic resistance. We performed qPCR to compare genome copy numbers for cultures infected with purified EBs of MCR and the parental MoPn at different time points along the developmental cycle. Interestingly, the fold increases in the genome copy number at 8 and 16 h, compared to 2 h postinoculation, in MCR-infected cultures, were significantly lower than those in MoPn-infected cultures (Fig. 10A). However, the difference disappeared 24 and 30 h postinoculation. These data suggest that MCR suffers growth deficiency at an early stage of the developmental cycle. It should be pointed out that the lower growth rate of MCR prior to 16 h was not due to a lower inoculum. In fact, qPCR analyses showed a slightly higher number of input EBs for MCR than for MoPn.

FIG 10.

Growth defects in MCR and lack of resistance in the slow-growing C. trachomatis A. (A) C. muridarum genome copy numbers in cells infected with MoPn or MCR at the indicated hours postinoculation were determined by qPCR. Note the relative genome copy number on the y axis is shown on a logarithmic scale. **, statistically highly significant differences in the fold of genome copy number increase between MoPn and MCR (P < 0.01, two-tailed Student's t test). The cycle threshold numbers for MoPn and MCR at the end of 2 h attachment/entry period were 22.87 ± 0.42 and 22.32 ± 0.33, respectively, indicating a slightly higher inoculating dose for MCR than for MoPn (P < 0.05). (B) Inhibition of the slow-growing C. trachomatis A by CF0001 and CF0002. HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis A (HAR-39) EBs at an MOI of 0.2. Treatment started 2 h after inoculation. At 36 h, infected HeLa cells were lysed for the determination of recoverable IFU by using McCoy cells. Cultures with 0 μM CF0001 and CF0002 were treated with 1% DMSO.

To deduce whether the growth defect may be the cause of increased resistance to benzylidene acylhydrazides in MCR, we performed inhibition tests for C. trachomatis A, an ocular pathogen that grows slowly in the genital epithelial HeLa cells (46). We found that the slow-growing organism is also highly susceptible to both CF0001 and CF0002 (Fig. 10B). In fact, the apparent MICs for C. trachomatis A (80 μM) were even slightly lower than those for the fast-growing wild-type MoPn (100 μM). Therefore, the early growth defect in MCR is unlikely to be responsible for the resistant phenotype.

Unsuccessful isolation of additional resistant mutants.

Alongside the experiments leading to the isolation of MCR, we attempted but failed to isolate CF0001-resistant mutants from C. trachomatis L2. After MCR was isolated, we again attempted to isolate resistant mutants from C. trachomatis L2 and additional mutants from MoPn. For both strains, the starting libraries were nonmutagenized stocks and stocks harvested from cultures exposed to different doses of ethyl methanesulfonate, a DNA-damaging agent that has been used to efficiently mutagenize chlamydiae (34, 47, 48). However, we were unable to isolate any additional resistant mutants in 5 repeated attempts for each bacterium. In total, 1.2 × 108 IFU of MoPn and 6 × 108 IFU of C. trachomatis L2 were used as starting inocula. Since some mutations created by the mutagen would certainly lead to slower growth, failure to isolate additional resistant variants is consistent with the notion that the early cycle growth defect is not the cause for resistance in MCR. Our inability to isolate additional mutants despite extensive efforts further suggests the possibility that resistance to these compounds is a complex phenotype, and the derivation of MCR represented an extremely rare event.

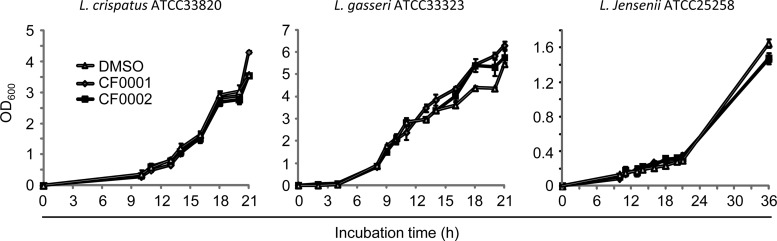

Lactobacillus growth is not affected by CF0001 and CF0002.

Lactobacilli, which dominate the vaginal microbiome, play protective roles against pathogens (49). Therefore, we assessed the effects of CF0001 and CF0002 on the growth of three common vaginal Lactobacillus species, L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii (49). Significantly, at 100 μM, neither compound exhibited an effect on the growth of any of the three strains (Fig. 11), suggesting that benzylidene acylhydrazides can inhibit chlamydiae without affecting the growth of vaginal probiotic lactobacilli.

FIG 11.

Lack of effects of CF0001 and CF0002 on growth of vaginal Lactobacillus spp. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 with fresh MRS broth containing 100 μM CF0001, 100 μM CF0002, or 1% DMSO. OD600 values were recorded at the indicated hours postinoculation.

DISCUSSION

Benzylidene acylhydrazides as potential antichlamydials.

We have identified benzylidene acylhydrazides, exemplified by CF0001 and CF0002, as inhibitors of chlamydiae. Although benzylidene acylhydrazides and salicylidene acylhydrazides are close analogs, three lines of evidence suggest that these two classes of compounds inhibit chlamydiae through distinct mechanisms. First, while the antichlamydial effect of salicylidene acylhydrazides depends on iron starvation and T3SS inhibition, as demonstrated previously (26) and in this work, chlamydial growth inhibition by benzylidene acylhydrazides is completely independent of iron deprivation (Fig. 3). Second, the benzylidene acylhydrazide-resistant variant MCR does not show cross-resistance to salicylidene acylhydrazides (Fig. 5). Finally, a very recently published study of a C. trachomatis mutant selected for resistance to iron-saturated INP0341, a salicylidene acylhydrazide, suggests that mutations in the protoporphyrin oxidase (HemG) mediate resistance to salicylidene acylhydrazides (50). Neither HemG nor the other mutated gene found in the INP0341-resistant variant is also mutated in MCR; in addition, there do not appear to be any connections between the genes affected in the INP0341-resistant chlamydiae and those mutated in MCR. Thus, benzylidene acylhydrazides are novel antichlamydials. Significantly, neither CF0001 nor CF0002 demonstrates detectable toxicity to the host cells or vaginal probiotic lactobacilli at concentrations effective against chlamydiae. The lack of inhibition of lactobacilli is a particularly attractive feature of benzylidene acylhydrazides in consideration of evaluating them as therapeutic candidates for chlamydial infections because current antichlamydials also kill lactobacilli, and their use often results in yeast vaginitis (51).

As with any antimicrobial, an important question with benzylidene acylhydrazides is the identity of their molecular target. Although salicylidene acylhydrazides are T3SS inhibitors, two facts suggest that benzylidene acylhydrazides are unlikely to affect the chlamydial T3SS. First, neither CF0001 nor CF0002 inhibits T3S (Fig. 1C and 5B). In addition, no mutation was present in the genes encoding the chlamydial T3SS components in MCR.

We have evaluated roles of the four SNPs identified in MCR (Table 1) in resistance to benzylidene acylhydrazides. Despite major efforts, we have not been able to pinpoint a particular affected gene encoding the direct target or regulating susceptibility, due to limitations in each set of experiments. Thus, even though C. pneumoniae, which similarly to MCR bears the A228V substitution in its MOMP, is highly susceptible to CF0001 (Fig. 6), it is still possible that the A228V mutation is necessary for resistance in MCR because of other amino acid changes in MOMP (particularly changes within the transmembrane domains of the protein) between C. muridarum and C. pneumoniae (52). The decreased ATP/ADP translocase expression in MCR (Fig. 7B) and the lack of effects of CF0001 and CF0002 on the ability of the translocase to transport nucleotides (Fig. 7C) suggest that the translocase does not mediate the entry of the inhibitors. However, it cannot be ruled out that a hypothetical benzylidene acylhydrazide metabolite, derived by the host cells and being responsible for inhibition of chlamydiae, uses the translocase to enter chlamydiae. Likewise, a lack of inhibition of the transcription activation activity of GrgA by the inhibitors suggests that the transcription factor is not a direct target of inhibitors. However, these findings do not exclude the possibility that a host or chlamydia-derived metabolite affects the activity of GrgA. Finally, even though the CT135 frameshift mutations in LC-CtD and EC-CtD do not seem to affect inhibition efficiency of CF0001 and CF0002, it is important to notice that the effect of SNP3 of MCR on TC0412 expression and the effect of the frameshift in LC-CtD on CT135 expression may not be identical if translation reinitiation occurs in the chlamydial mutants. Whereas an N-terminally truncated TC0412 might be generated in MCR as a result of translation reinitiation at codon 45, reinitiation in LC-CtD would not occur until codon 86 (translation table not shown).

Two findings indicate that the growth defect of MCR is an unlikely nonspecific cause for resistance. First, the slow-growing C. trachomatis A is highly susceptible to both CF0001 and CF0002 (Fig. 10). Second, some of the mutants created after EMS mutagenization must also suffer growth deficiency, but these were not selected for by CF0001. Our inability to isolate additional mutants, even from stocks created from cultures treated with high doses of ethyl methanesulfonate, suggests the possibility that interplay between multiple gene defects is required for resistance.

Three strategies could be employed in the future to identify the target(s) and/or mechanism(s) for resistance. First, since chlamydiae, including C. muridarum, can now be transformed (53–59), it may be possible to determine which mutated gene(s) in MCR confers resistance to benzylidene acylhydrazides by expression of the wild-type copies of mutated genes either individually or in combination and by examining whether this expression restores susceptibility to this class of compound. Potential pitfalls for this reverse-genetics approach include limited accommodation capacity in the shuttle vector, which is already about 10 kb, and a possible need for knocking out the chromosomal alleles to achieve a clear background. Second, chlamydial variants with a null mutation(s) of the genes mutated in MCR could be generated by a methodology developed through chemical mutagenesis (47) or group II intron-mediated gene inactivation (59), provided that the genes to be targeted are nonessential. If none of the single mutations is sufficient to cause resistance, secondary and even tertiary mutations could be created likewise. Finally, since recombinant chlamydiae can be generated from strains with resistance to different inhibitors (60, 61), it should be possible to recombine the genome of MCR with another chlamydial genome to determine which SNP(s) is required and sufficient for resistance.

Functions of proteins affected by SNPs in MCR.

Interestingly, MCR displays an early phase growth defect, indicating an important role for one or more of the four genes mutated in MCR in the regulation of chlamydial growth. A cDNA microarray study has demonstrated that transcription of the ATP/ADP translocase in C. trachomatis occurs immediately after entry, suggesting a critical role of the translocase in supplying ATP to the organism during the early developmental phase (62). Therefore, a reduction in ATP/ADP translocase expression is most consistent with the growth deficiency phenotype.

In addition to the decreased ATP/ADP translocase expression, the R51G mutation in GrgA may also contribute to the growth defect. We envision two potential and mutually nonexclusive mechanisms by which R51G GrgA delays the growth. First, the loss of transcription activation activity in R51G GrgA may be partially or completely responsible for the decreased expression level of the translocase, despite the presence of a mutation upstream of the ATP/ADP translocase open reading frame. In vitro studies suggest that GrgA functions as a general transcription activator for genes dependent on the primary σ factor, σ66. Consistent with a potential role of GrgA in transcription of the translocase gene is the existence of putative −35 and −10 elements of σ66-dependent promoters (not shown) upstream of the predicted transcription start site (Fig. 7). Second, a functional defect of GrgA likely affects expression of additional genes whose products are also important for early chlamydial development. Efforts are being directed at understanding how GrgA regulates chlamydial gene transcription in vivo.

MOMP has been studied extensively for its abundance and immunogenicity (32, 63–65). Despite a lack of direct experimental data, a regulatory role for MOMP in chlamydial development and growth is conceivable since MOMP functions as a porin for ions (39–41). Accordingly, the A228V mutation in MOMP could contribute to the early growth defect in MCR.

TC0412, a 360-amino-acid protein, is truncated at residue 24 in MCR (Table 1). This truncation may or may not have a significant effect on gene function since translation could be reinitiated at codon 45. Regardless, the functions of TC0412 or its homologs in other Chlamydia species are unlikely to be essential for bacterial growth in cell culture since frameshift mutations have been detected in various locations of the gene and in numerous strains (30, 66–69). However, in vivo studies have demonstrated CT135 as a virulence determinant in C. trachomatis infection (30, 45). Accordingly, a frameshift at codon 45 in CT135 resulted in longer duration of pathogen shedding in intravaginally inoculated mice compared to a frameshift at codon 86 (30).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that benzylidene acylhydrazides are a novel class of antichlamydials. Unlike salicylidene acylhydrazides, benzylidene acylhydrazides inhibit chlamydiae through a mechanism that is independent of iron starvation and T3SS inhibition. Well tolerated by host cells and Lactobacillus, which is a dominating constituent of vaginal microbiota in most healthy women (49), benzylidene acylhydrazides are of potential therapeutic value. Finally, the benzylidene acylhydrazide-resistant chlamydial variant MCR may serve as a useful model organism for investigation of the inhibition mechanism and the function and regulation of proteins affected by the SNPs in the variant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guangming Zhong (University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio) for supplying C. trachomatis A, anti-LPS, anti-MOMP (MC22), and anti-AR39 and Anthony Maurelli (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) for supplying E. coli strains for the ATP/ADP translocase experiments. We also thank Daniel D. Rockey (Oregon State University), Derek Fisher (Southern Illinois University), and Muhammad Yasir, a former member of the Fan lab, for useful discussions, and Kai Zhang for preparation of Fig. 1A and B and Fig. 5A. Finally, we thank Rémi Caraballo and Yesmin Luna for technical assistance.

This work was supported by an extramural National Institutes of Health grant (AI071954) and a New Jersey Health Foundation grant (PC7-13) to H.F., a Swedish Research Council grant to M.E., an intramural NIH grant to H.D.C., an Astrazeneca Sweden grant to Å.G., and a National Natural Science Foundation of China grant (no. 31370209) to X.B. We also thank the Umeå Centre for Microbial Research and Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden for support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Stephens RS, Myers G, Eppinger M, Bavoil PM. 2009. Divergence without difference: phylogenetics and taxonomy of Chlamydia resolved. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 55:115–119. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell LA, Kuo CC, Grayston JT. 1998. Chlamydia pneumoniae and cardiovascular disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:571–579. 10.3201/eid0404.980407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little CS, Hammond CJ, MacIntyre A, Balin BJ, Appelt DM. 2004. Chlamydia pneumoniae induces Alzheimer-like amyloid plaques in brains of BALB/c mice. Neurobiol. Aging 25:419–429. 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00127-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balin BJ, Little CS, Hammond CJ, Appelt DM, Whittum-Hudson JA, Gerard HC, Hudson AP. 2008. Chlamydophila pneumoniae and the etiology of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 13:371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. 2013. CDC fact sheet. STD trends in the United States: 2011 national data for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. 2014. CDC fact sheet. STD trends in the United States: 2012 national data for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Maza L, Pal S, Khamesipour A, Peterson E. 1994. Intravaginal inoculation of mice with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar results in infertility. Infect. Immun. 62:2094–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter TW, Miranpuri GS, Ramsey KH, Poulsen CE, Byrne GI. 1997. Reactivation of chlamydial genital tract infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:2067–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Lei L, Chang X, Li Z, Lu C, Zhang X, Wu Y, Yeh IT, Zhong G. 2010. Mice deficient in MyD88 develop a Th2-dominant response and severe pathology in the upper genital tract following Chlamydia muridarum infection. J. Immunol. 184:2602–2610. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan H. 2012. Blindness-causing trachomatous trichiasis biomarkers sighted. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53:2560. 10.1167/iovs.12-9835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton MJ, Mabey DCW. 2009. The global burden of trachoma: a review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e460. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. 2007. Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis entry into nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 75:3925–3934. 10.1128/IAI.00106-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. 2007. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:11430–11435. 10.1073/pnas.0703218104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754–759. 10.1126/science.282.5389.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galan JE, Wolf-Watz H. 2006. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature 444:567–573. 10.1038/nature05272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mota LJ, Cornelis GR. 2005. The bacterial injection kit: type III secretion systems. Ann. Med. 37:234–249. 10.1080/07853890510037329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornelis GR. 2006. The type III secretion injectisome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:811–825. 10.1038/nrmicro1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh P. 2004. Process of protein transport by the type III secretion system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:771–795. 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.771-795.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyser P, Elofsson M, Rosell S, Wolf-Watz H. 2008. Virulence blockers as alternatives to antibiotics: type III secretion inhibitors against Gram-negative bacteria. J. Intern. Med. 264:17–29. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kauppi AM, Nordfelth R, Uvell H, Wolf-Watz H, Elofsson M. 2003. Targeting bacterial virulence: inhibitors of type III secretion in Yersinia. Chem. Biol. 10:241–249. 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordfelth R, Kauppi AM, Norberg HA, Wolf-Watz H, Elofsson M. 2005. Small-molecule inhibitors specifically targeting type III secretion. Infect. Immun. 73:3104–3114. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3104-3114.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey L, Gylfe A, Sundin C, Muschiol S, Elofsson M, Nordstrom P, Henriques-Normark B, Lugert R, Waldenstrom A, Wolf-Watz H, Bergstrom S. 2007. Small molecule inhibitors of type III secretion in Yersinia block the Chlamydia pneumoniae infection cycle. FEBS Lett. 581:587–595. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf K, Betts HJ, Chellas-Gery B, Hower S, Linton CN, Fields KA. 2006. Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis with a small molecule inhibitor of the Yersinia type III secretion system disrupts progression of the chlamydial developmental cycle. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1543–1555. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05347.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong S, Lei L, Chang X, Belland R, Zhong G. 2011. Chlamydia trachomatis secretion of hypothetical protein CT622 into host cell cytoplasm via a secretion pathway that can be inhibited by the type III secretion system inhibitor compound 1. Microbiology 157:1134–1144. 10.1099/mic.0.047746-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muschiol S, Bailey L, Gylfe A, Sundin C, Hultenby K, Bergstrom S, Elofsson M, Wolf-Watz H, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. 2006. A small-molecule inhibitor of type III secretion inhibits different stages of the infectious cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14566–14571. 10.1073/pnas.0606412103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slepenkin A, Enquist PA, Hagglund U, de la Maza LM, Elofsson M, Peterson EM. 2007. Reversal of the antichlamydial activity of putative type III secretion inhibitors by iron. Infect. Immun. 75:3478–3489. 10.1128/IAI.00023-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forthal DN, Phan TB, Slepenkin AV, Landucci G, Chu H, Elofsson M, Peterson E. 2012. In vitro anti-HIV-1 activity of salicylidene acylhydrazide compounds. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40:354–360. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauppi AM, Nordfelth R, Hagglund U, Wolf-Watz H, Elofsson M. 2003. Salicylanilides are potent inhibitors of type III secretion in Yersinia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 529:97–100. 10.1007/0-306-48416-1_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlgren MK, Zetterstrom CE, Gylfe S, Linusson A, Elofsson M. 2010. Statistical molecular design of a focused salicylidene acylhydrazide library and multivariate QSAR of inhibition of type III secretion in the Gram-negative bacterium Yersinia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18:2686–2703. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sturdevant GL, Kari L, Gardner DJ, Olivares-Zavaleta N, Randall LB, Whitmire WM, Carlson JH, Goheen MM, Selleck EM, Martens C, Caldwell HD. 2010. Frameshift mutations in a single novel virulence factor alter the in vivo pathogenicity of Chlamydia trachomatis for the female murine genital tract. Infect. Immun. 78:3660–3668. 10.1128/IAI.00386-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene W, Xiao Y, Huang Y, McClarty G, Zhong G. 2004. Chlamydia-infected cells continue to undergo mitosis and resist induction of apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 72:451–460. 10.1128/IAI.72.1.451-460.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. 1981. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 31:1161–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balakrishnan A, Patel B, Sieber SA, Chen D, Pachikara N, Zhong G, Cravatt BF, Fan H. 2006. Metalloprotease inhibitors GM6001 and TAPI-0 inhibit the obligate intracellular human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis by targeting peptide deformylase of the bacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 281:16691–16699. 10.1074/jbc.M513648200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao X, Pachikara ND, Oey CB, Balakrishnan A, Westblade LF, Tan M, Chase T, Nickels BE, Fan H. 2011. Non-coding nucleotides and amino acids near the active site regulate peptide deformylase expression and inhibitor susceptibility in Chlamydia trachomatis. Microbiology 157:2569–2581. 10.1099/mic.0.049668-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao X, Nickels BE, Fan H. 2012. Chlamydia trachomatis protein GrgA activates transcription by contacting the nonconserved region of σ66. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:16870–16875. 10.1073/pnas.1207300109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher DJ, Fernandez RE, Maurelli AT. 2013. Chlamydia trachomatis transports NAD via the Npt1 ATP/ADP translocase. J. Bacteriol. 195:3381–3386. 10.1128/JB.00433-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, Hickey EK, Peterson J, Utterback T, Berry K, Bass S, Linher K, Weidman J, Khouri H, Craven B, Bowman C, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Nelson W, DeBoy R, Kolonay J, McClarty G, Salzberg SL, Eisen J, Fraser CM. 2000. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1397–1406. 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Findlay HE, McClafferty H, Ashley RH. 2005. Surface expression, single-channel analysis and membrane topology of recombinant Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. BMC Microbiol. 5:5. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wyllie S, Ashley RH, Longbottom D, Herring AJ. 1998. The major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia psittaci functions as a porin-like ion channel. Infect. Immun. 66:5202–5207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bavoil P, Ohlin A, Schachter J. 1984. Role of disulfide bonding in outer membrane structure and permeability in Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 44:479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun G, Pal S, Sarcon AK, Kim S, Sugawara E, Nikaido H, Cocco MJ, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. 2007. Structural and functional analyses of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 189:6222–6235. 10.1128/JB.00552-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tjaden J, Winkler HH, Schwöppe C, Van Der Laan M, Möhlmann T, Neuhaus HE. 1999. Two nucleotide transport proteins in Chlamydia trachomatis, one for net nucleoside triphosphate uptake and the other for transport of energy. J. Bacteriol. 181:1196–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albrecht M, Sharma CM, Reinhardt R, Vogel J, Rudel T. 2010. Deep sequencing-based discovery of the Chlamydia trachomatis transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:868–877. 10.1093/nar/gkp1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomson NR, Holden MTG, Carder C, Lennard N, Lockey SJ, Marsh P, Skipp P, O'Connor CD, Goodhead I, Norbertzcak H, Harris B, Ormond D, Rance R, Quail MA, Parkhill J, Stephens RS, Clarke IN. 2008. Chlamydia trachomatis: genome sequence analysis of lymphogranuloma venereum isolates. Genome Res. 18:161–171. 10.1101/gr.7020108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturdevant GL, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Zhou B, Song L, Caldwell HD. 2014. Infectivity of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-deficient, CT135-null, and double-deficient strains in female mice. Pathog. Dis. 71:90–92. 10.1111/2049-632X.12121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyairi I, Mahdi OS, Ouellette SP, Belland RJ, Byrne GI. 2006. Different growth rates of Chlamydia trachomatis biovars reflect pathotype. J. Infect. Dis. 194:350–357. 10.1086/505432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kari L, Goheen MM, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Virok D, Rajaram K, Endresz V, McClarty G, Nelson DE, Caldwell HD. 2011. Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:7189–7193. 10.1073/pnas.1102229108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen BD, Valdivia RH. 2012. Virulence determinants in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis revealed by forward genetic approaches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:1263–1268. 10.1073/pnas.1117884109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. 2011. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4680–4687. 10.1073/pnas.1002611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engström P, Nguyen BD, Normark J, Nilsson I, Bastidas RJ, Gylfe Å, Elofsson M, Fields KA, Valdivia RH, Wolf-Watz H, Bergström S. 2013. Mutations in hemG mediate resistance to salicylidene acylhydrazides, demonstrating a novel link between protoporphyrinogen oxidase (HemG) and Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity. J. Bacteriol. 195:4221–4230. 10.1128/JB.00506-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill LV, Embil JA. 1986. Vaginitis: current microbiologic and clinical concepts. CMAJ 134:321–331 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaltenboeck B, Kousoulas KG, Storz J. 1993. Structures of and allelic diversity and relationships among the major outer membrane protein (ompA) genes of the four chlamydial species. J. Bacteriol. 175:487–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN. 2011. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002258. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu S, Battaglia L, Bao X, Fan H. 2013. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase as a selection marker for chlamydial transformation. BMC Res. Notes 6:377. 10.1186/1756-0500-6-377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gong S, Yang Z, Lei L, Shen L, Zhong G. 2013. Characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-encoded open reading frames. J. Bacteriol. 195:3819–3826. 10.1128/JB.00511-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song L, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Kari L, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Watkins H, Zhou B, Sturdevant GL, Porcella SF, McClarty G, Caldwell HD. 2013. Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-encoded Pgp4 is a transcriptional regulator of virulence-associated genes. Infect. Immun. 81:636–644. 10.1128/IAI.01305-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Chen C, Gong S, Hou S, Qi M, Liu Q, Baseman J, Zhong G. 2014. Transformation of Chlamydia muridarum reveals a role for Pgp5 in suppression of plasmid-dependent gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 196:989–998. 10.1128/JB.01161-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickstrum J, Sammons LR, Restivo KN, Hefty PS. 2013. Conditional gene expression in Chlamydia trachomatis using the tet system. PLoS One 8:e76743. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson CM, Fisher DJ. 2013. Site-specific, insertional inactivation of incA in Chlamydia trachomatis using a group II intron. PLoS One 8:e83989. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeffrey BM, Suchland RJ, Eriksen SG, Sandoz KM, Rockey DD. 2013. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of in vitro-generated Chlamydia trachomatis recombinants. BMC Microbiol. 13:142. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srinivasan T, Bruno WJ, Wan R, Yen A, Duong J, Dean D. 2012. In vitro recombinants of antibiotic-resistant Chlamydia trachomatis strains have statistically more breakpoints than clinical recombinants for the same sequenced loci and exhibit selection at unexpected loci. J. Bacteriol. 194:617–626. 10.1128/JB.06268-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Belland RJ, Zhong G, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Sharma J, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. 2003. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8478–8483. 10.1073/pnas.1331135100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baehr W, Zhang YX, Joseph T, Su H, Nano FE, Everett KD, Caldwell HD. 1988. Mapping antigenic domains expressed by Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:4000–4004. 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su H, Caldwell HD. 1992. Immunogenicity of a chimeric peptide corresponding to T helper and B cell epitopes of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. J. Exp. Med. 175:227–235. 10.1084/jem.175.1.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng X, Pal S, de la Maza LM, Peterson EM. 1992. Characterization of the humoral response induced by a peptide corresponding to variable domain IV of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E. Infect. Immun. 60:3428–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suchland RJ, Jeffrey BM, Xia M, Bhatia A, Chu HG, Rockey DD, Stamm WE. 2008. Identification of concomitant infection with Chlamydia trachomatis IncA-negative mutant and wild-type strains by genomic, transcriptional, and biological characterizations. Infect. Immun. 76:5438–5446. 10.1128/IAI.00984-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borges V, Ferreira R, Nunes A, Sousa-Uva M, Abreu M, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP. 2013. Effect of long-term laboratory propagation on Chlamydia trachomatis genome dynamics. Infect. Genet. Evol. 17:23–32. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramsey KH, Sigar IM, Schripsema JH, Denman CJ, Bowlin AK, Myers GA, Rank RG. 2009. Strain and virulence diversity in the mouse pathogen Chlamydia muridarum. Infect. Immun. 77:3284–3293. 10.1128/IAI.00147-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell M, Darville T, Chandra-Kuntal K, Smith B, Andrews CW, O'Connell CM. 2011. Infectivity acts as in vivo selection for maintenance of the chlamydial cryptic plasmid. Infect. Immun. 79:98–107. 10.1128/IAI.01105-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]