Abstract

Objectives

Stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1α is a potent endogenous endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) chemokine and key angiogenic precursor. Recombinant SDF-1α has been demonstrated to improve neovasculogenesis and cardiac function after myocardial infarction (MI) but SDF-1α is a bulky protein with a short half-life. Small peptide analogs might provide translational advantages, including ease of synthesis, low manufacturing costs, and the potential to control delivery within tissues using engineered biomaterials. We hypothesized that a minimized peptide analog of SDF-1α, designed by splicing the N-terminus (activation and binding) and C-terminus (extracellular stabilization) with a truncated amino acid linker, would induce EPC migration and preserve ventricular function after MI.

Methods

EPC migration was first determined in vitro using a Boyden chamber assay. For in vivo analysis, male rats (n=48) underwent left anterior descending coronary artery ligation. At infarction, the rats were randomized into 4 groups and received peri-infarct intramyocardial injections of saline, 3 μg/kg of SDF-1α, 3 μg/kg of spliced SDF analog, or 6 μg/kg spliced SDF analog. After 4 weeks, the rats underwent closed chest pressure volume conductance catheter analysis.

Results

EPCs showed significantly increased migration when placed in both a recombinant SDF-1α and spliced SDF analog gradient. The rats treated with spliced SDF analog at MI demonstrated a significant dose-dependent improvement in end-diastolic pressure, stroke volume, ejection fraction, cardiac output, and stroke work compared with the control rats.

Conclusions

A spliced peptide analog of SDF-1α containing both the N- and C- termini of the native protein induced EPC migration, improved ventricular function after acute MI, and provided translational advantages compared with recombinant human SDF-1α.

After myocardial infarction (MI), microvascular dysfunction has been shown to be an important independent predictor of ventricular remodeling, reinfarction, heart failure, and death.1 Immediately after MI, the extent of microvascular obstruction and infarct size increases significantly during the first 48 hours and significant progressive microvascular and myocardial injury occurs well beyond the infarct zone, even with reperfusion.2,3 This is important, because an increased number of capillaries in these areas of ischemic myocardium has been correlated with an increase in contractility and function under stress conditions.4 The endogenous machinery to repair injured and ischemic myocardium is inadequate, and tremendous resources have been devoted to developing molecular therapies that enhance both the microvascular perfusion and the function of ischemic or infarcted myocardium. A significant portion of this work has focused on angiogenic cytokines, including fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, placental growth factor, and the potent endothelial progenitor stem cell (EPC) chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α).

Experimentally, SDF-1α has been shown to be an effective angiogenic cytokine therapy. In an animal model of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, peri-infarct myocardial injection of SDF-1α caused significantly enhanced myocardial EPC density, increased vasculogenesis, and augmented myocardial function by enhancing perfusion, reversing cellular ischemia, increasing cardiomyocyte viability, and preserving the ventricular geometry.5,6

Despite promising preclinical results, SDF-1α has several features that are not optimal for a widely translatable therapy. This large, 10-kD protein is quickly degraded by proteases that are activated at sites of injury, including dipeptidyl peptidase IV and matrix metalloproteinase-2.7,8 In addition, the delivery of SDF-1α would be further complicated by the high manufacturing costs and rapid diffusion of the chemokine away from the targeted site.9 We believe that small peptide analogs, functionally comparable to native SDF-1α, could provide translational advantages, including ease of synthesis, low manufacturing costs, and the potential to control delivery within tissues using engineered biomaterials.

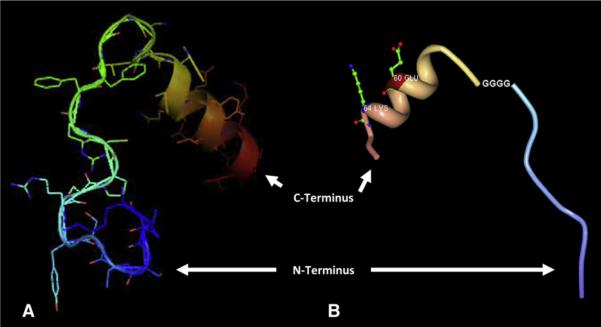

Previous studies have demonstrated that a minimized peptide analog of SDF-1α, designed by deleting the large central β-sheet region and splicing the N-terminus (activation and binding site) and C-terminus (extracellular stabilization region) with a truncated amino acid linker consisting of 4 glycines, would induce in vitro intracellular calcium release and T1 cell migration (Figure 1).10 In the present study, we hypothesized that this small, spliced SDF-1α analog would induce EPC migration and preserve ventricular function after MI in a similar fashion to native SDF-1α. In doing so, this truncated peptide analog would provide a novel foundation for the clinical translation of cytokine-based neovasculogenic therapy, as well as a logical jumping off point for the rational design and re-engineering of the SDF-1α peptide to enhance stability and in vivo function.

FIGURE 1.

Depiction of N- and C-termini of stromal cell-derived factor (SDF) linked by 4 glycines (A), with and (B) without side chains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide Synthesis

The spliced SDF-1α analog peptide was synthesized using solid phase peptide synthesis (AnaSpec, San Jose, Calif), which involves the incorporation of N-a-amino acids into a peptide of any desired sequence with one end of the sequence remaining attached to a solid support matrix. After the desired sequence of amino acids has been obtained, the peptide is removed from the polymeric support.

Cell Isolation

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from the long bones of adult male green fluorescent protein-Wistar rats using density-gradient centrifugation with Histopaque 1083 (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo) and cultured in endothelial basal medium-2 supplemented with EGM-2 Singlequot (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing human epidermal growth factor, fetal bovine serum, vascular endothelial growth factor, human fibroblast growth factor-B, R3-insulin-like growth factor-1, ascorbic acid, heparin, gentamicin, and amphotericin-B. The combination of endothelial-specific media and the removal of nonadherent MNCs was intended to select for the EPC phenotype.

Functional Characterization of Isolated EPCs Using Boyden Chamber Assay

The widely used Boyden chamber assay (Neuro Probe, Inc, Gaithersburg, Md) was used to assess EPC migration.11–13 In brief, 8-μm filters were loaded into control and experimental chambers. The 14-day EPCs, cultured in endothelial-specific media on vitronectin-coated plates, were trypsinized, counted, and brought to a concentration of 90 cells/μL in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). The bottom chamber of the control and experimental chambers were loaded with DPBS, 50 ng/mL recombinant SDF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn) in DPBS, 50 ng/mL of the spliced SDF analog in DPBS, or 100 ng/mL of the spliced SDF analog in DPBS. A 560-μL cell suspension was added to the top chamber of each. All 3 chambers were incubated at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide for 4 hours. The cells remaining in the top chamber were wiped clean with a cotton swab, and the filter was removed. The slides were visualized on a DF5000B Leica Fluorescent scope and analyzed using LASAF, version 2.0.2, software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Boyden chamber analysis was performed in triplicate.

Animal Care and Biosafety

Male Lewis rats weighing 250 to 300 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories International Inc (Wilmington, Mass). Food and water were provided ad lib. This investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Pennsylvania (protocol no. 802076).

Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Model

The rats were anesthetized with ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (7.5 mg/kg), intubated with a 16-gauge catheter, and mechanically ventilated (Hallowell EMC, Hallowell Engineering and Manufacturing Corp, Pittsfield, Mass) with tidal volume (Vt) (mL) = 6.2 × M1.01 (where M is the animal mass in kilograms) and respiratory rate (min−1) = 53.5 × M−0.26.14 A thoracotomy was performed in the left fourth intercostal space, and a 7–0 polypropylene suture was placed around the mid-left anterior descending coronary artery 2 mm inferior to the left atrial appendage and ligated to produce a large anterolateral MI of 30% of the left ventricle. The extent of infarction was highly reproducible, and progression to cardiomyopathy has been well documented.5,6,15–17 Immediately after MI, the rats were randomized into 4 groups and received peri-infarct intramyocardial injections of saline (n=12), SDF-1α (3 μg/kg, n=12), spliced SDF analog at 3 μg/kg (n = 12), or spliced SDF analog at 6 μg/kg (n 12). The rats were injected using a 30-gauge needle into 5 predetermined regions in the peri-infarct border zone, defined as 1 microscopic field lateral to the myocardial scar.18 The thoracotomy was then closed, and the rats were implanted with identification microchips (BioMedic Data Systems Inc, Boise, Idaho) and recovered. Buprenorphine (0.5 mg/kg) was administered for postoperative analgesia. Identification data were maintained by an investigator who did not participate in the subsequent data collection or analysis. All 3 experimental treatment groups received subcutaneous injections of 40 μg/kg liquid sargramostim (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor), diluted in saline, for a total volume of 200 μL immediately postoperatively and on postoperative day 1. An additional control group (n = 12) also received subcutaneous injections of 40 mg/kg of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor immediately postoperatively and on postoperative day 1, in addition to peri-infarct intramyocardial injections of saline.

Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment

At 4 weeks after left anterior descending coronary artery ligation, the control and experimental rats (control group, n = 12; SDF-1α at 3 μg/kg, n = 12; spliced SDF analog at 3 μg/kg, n = 12; and spliced SDF analog at 6 μg/kg, n = 12) underwent invasive hemodynamic measurements with a pressure-volume conductance catheter (SPR-869, Millar Instruments Inc, Houston, Tex). The catheter was calibrated using 5-point cuvette linear interpolation with parallel conductance subtraction by the hypertonic saline method.14 The rats were anesthetized, and the catheter was introduced into the left ventricle with a closed-chest approach by way of the right carotid artery. Measurements were obtained before and during inferior vena cava occlusion to produce static and dynamic pressure-volume loops under varying load conditions. The data were recorded and analyzed using Lab-Chart, version 6, software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, Colo) and ARIA pressure volume analysis software (Millar Instruments).

Statistical Analysis

The unpaired Student t test was used to compare the groups. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

EPCs Cultured in Endothelial-Specific Media Exhibited Enhanced Migration When Exposed to Spliced SDF Analog Gradient

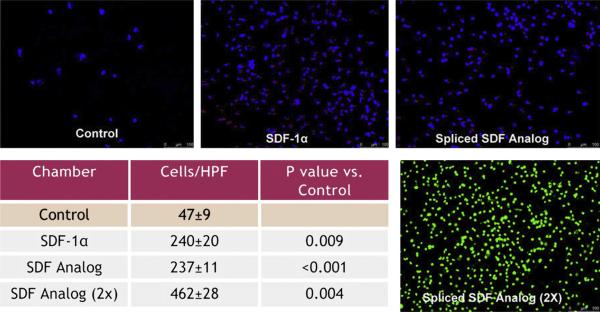

Using a Boyden chamber assay, the 14-day endothelial progenitor cells showed significantly increased migration when placed in both a recombinant human SDF-1α and spliced SDF analog gradient (control group, 47 ± 9 cells/high-power field [HPF] vs SDF-1α, 240 ± 20 cells/HPF, P = .009; control vs spliced SDF analog, 237 ± 11 cells/HPF, P <.001; and control vs spliced SDF analog [2×], 461 ± 28 cells/HPF, P = .004; Figure 2). In addition, we were able to demonstrate a dose-response effect, showing that significantly more cells migrated in the [2×] spliced SDF analog gradient than in either the SDF-1α or [1×] spliced SDF analog gradient (P <.01 for both).

FIGURE 2.

Using Boyden chamber assay, isolated endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) showed increased migration when placed in SDF and spliced SDF analog gradients. Images are representative of Boyden chamber filters from each group. Green fluorescent protein–positive cells were used in the Spliced SDF Analog (23) image.

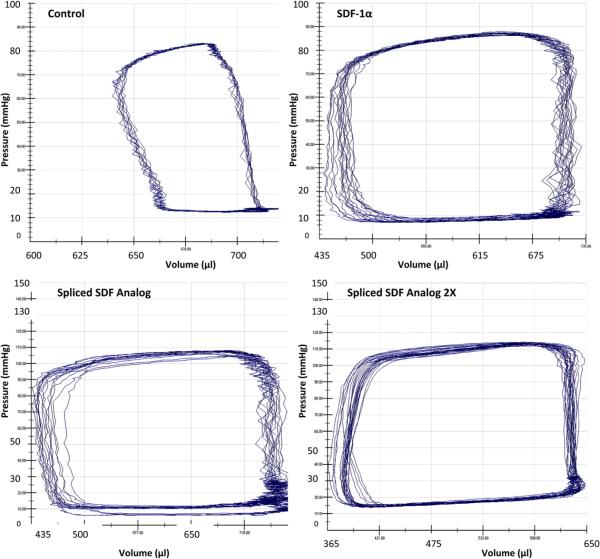

Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment Showed Dose-Dependent Improvement in Left Ventricular Function After Spliced SDF Analog Treatment

The rats treated with recombinant human SDF-1α and spliced SDF analog (both 3 and 6 μg/kg doses) exhibited statistically significant preservation of cardiac function compared with the control rats (Figure 3). The rats treated with the high-dose spliced SDF analog demonstrated a significant dose-dependent improvement in stroke volume, ejection fraction, cardiac output, and arterial elastance compared with the low-dose spliced SDF analog group. The high-dose spliced SDF analog group also demonstrated a significant improvement in ejection fraction and cardiac output compared with the recombinant human SDF-1α (3μg/kg) group (Table 1). The saline control group that received subcutaneous injections of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor was significantly inferior or equivalent to the saline-only control group for all parameters assessed (end diastolic pressure, 14.4 mm Hg, P = .17; stroke volume 157.9 μL, P = .05; ejection fraction, 21.6%, P = 0.11; cardiac output, 33,865.8 μL/min, P = .09; stroke work, 12,401.8 mm Hg/μL, P = 0.32; and arterial elastance, 0.67 mm Hg/μL, P = .12).

FIGURE 3.

Representative pressure-volume loops from all 4 experimental groups depicting greater ejection fraction and cardiac output in stromal cell-derived factor (SDF) and spliced SDF analog-treated groups compared with the control group.

TABLE 1.

Invasive hemodynamic assessment showing dose-dependent improvement in left ventricular function after spliced SDF analog treatment

| Spliced SDF peptide analog |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive hemodynamic assessment | Control group (n = 12) | rhSDF-1α (n = 12) | 3 μg/kg (n = 12) | 6 μg/kg (n = 12) |

| End-diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 18.5 ± 2 | 25.0 ± 2.5 | 23.4 ± 2 | 24.3 ± 2.5 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .03 | .05 | .04 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .31 | .43 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .39 | |||

| Stroke volume (μL) | 188.8 ± 14.5 | 261.2 ± 19.7 | 244.2 ± 20.2 | 290.4 ± 10.6 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .04 | .019 | .001 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .28 | .10 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .03 | |||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 24.37 ± 1.7 | 32.7 ± 2 | 30.57 ± 1.9 | 36.93 ± 1 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .02 | .013 | .001 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .22 | .04 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .005 | |||

| Cardiac output (μL/min) | 39,270 ± 2927 | 52,184 ± 3532 | 50,670 ± 4086 | 60,764 ± 2297 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .05 | .017 | .001 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .39 | .03 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .02 | |||

| Stroke work (mm Hg/μL) | 11,789 ± 1079 | 17,180 ± 1501 | 16,623 ± 1498 | 19,736 ± 1147 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .04 | .08 | .001 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .40 | .095 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .06 | |||

| Arterial elastance (mm Hg/μL) | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.02 |

| P value | ||||

| Versus control group | .07 | .07 | .001 | |

| Versus rhSDF group | .14 | .07 | ||

| Versus peptide 3 μg/kg | .008 | |||

rhSDF, Recombinant human stromal cell-derived factor.

DISCUSSION

Therapeutic angiogenesis is a clearly safe and feasible therapy for ischemic heart disease. However, despite a myriad of favorable experimental results, the body of clinical data is large and lacks a clear consensus. Several questions need to be answered before angiogenic cytokines can become a widely used and efficacious treatment. An ideal agent needs to be identified, followed by the ideal form of said angiogenic cytokine, and, finally, the optimal dose needs to be determined.19

We believe that SDF-1α, the most potent and specific angiogenic cytokine, is an ideal choice. Stromal cell- derived factor-1α, is a 68-amino acid peptide belonging to the CXC family of chemokines and is the sole ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor, CXCR4, through which its biologic effects are mediated. SDF-1α is a key regulator of physiologic cell motility both during embryogenesis and after birth and is constitutively expressed in a wide variety of cells, including endothelial cells, dendritic cells, and stromal cells.20 This powerful chemoattractant is significantly upregulated in response to both myocardial ischemia and infarction and has been shown to effect EPC proliferation and mobilization to induce vasculogenesis.21,22 Its sole target, the CXCR4 cell-surface antigen, is expressed in significant levels on CD34+ EPCs, and the expression of this receptor is related to efficient SDF-induced transendothelial migration.23 In addition, SDF has repeatedly been shown to play a critical role in the rescue of myocardial function and stem cell recruitment to the heart after MI.24–27 However, we do not believe that recombinant human SDF is the ideal form of this angiogenic cytokine for widespread translation. Small peptide analogs, functionally comparable to native SDF-1α, might provide translational advantages, including ease of synthesis, low manufacturing costs, and the potential to control delivery within tissues using engineered biomaterials. In the present study, we have demonstrated that a minimized peptide analog of SDF that spliced the receptor binding N-terminus and the extracellular stabilizing C-terminus with a 4-glycine amino acid chain could induce EPC migration and preserve ventricular function after MI in a similar fashion to SDF.

SDF cytokine therapy mobilizes marrow-based EPCs to form new microvasculature and perfuse ischemic myocardium. Using a Boyden chamber assay, we showed that endothelial progenitor cells exhibited significantly increased migration when placed in both a recombinant human SDF and a spliced SDF analog gradient. A dose-response effect was also apparent. This assay revealed that, despite the deletion of the large central β-sheet region, the spliced SDF analog retains the chemotactic homing mechanism of native SDF critical to myocardial EPC recruitment and vessel formation.

Endogenous revascularization for ischemic cardiomyopathy using SDF-mediated EPC chemokinesis enhances circulating EPC density and augments myocardial function by enhancing perfusion, reversing cellular ischemia, and increasing cardiomyocyte viability.5 It would follow logically that the spliced SDF analog would similarly be able to rescue myocardial function in the setting of acute ischemic insult if it retained a significant proportion of native SDF activity. The rats treated with recombinant human SDF and spliced SDF analog (both 3- and 6-μg/kg doses) exhibited statistically significant preservation of cardiac function compared with the control group. Also, the high-dose spliced SDF analog group demonstrated a significant improvement in the ejection fraction and cardiac output compared with the recombinant human SDF group. This in vivo evidence has demonstrated once again that the spliced SDF analog retains critical native SDF activity despite its truncated polypeptide sequence.

Experimentally, treatment with SDF has been effective at multiple different points. It has been delivered at the time of MI, such as was done in the present study, and up to 3 weeks after MI. We believe this microrevascularization strategy can serve as a primary therapy at any point in the disease process and can be used synergistically with traditional coronary revascularization methods. Small peptide analogs of SDF incorporated into sustained release vesicles could be delivered into the coronary circulation during any catheter-based intervention to augment collateralization. They could also be deployed during open cardiac procedures, either as a direct injection into areas of ischemic myocardium without graft-able target vessels or incorporated into an engineered biomaterial overlay. Additionally, SDF has been used to “supercharge” stem cell therapy.28 The potential clinical applications for SDF-based angiogenic therapy are limited only by the imagination and the restrictions imposed by the SDF molecule itself. The present study represents the first foray into the design and construction of a maximally efficient, translatable SDF molecule analog.

CONCLUSIONS

A spliced peptide analog of SDF-1α containing both the N- and C- termini of the native protein induced EPC migration, improved ventricular function after acute MI, and provided a novel foundation for the clinical translation of cytokine-based neovasculogenic therapy. The purpose of the present study was not to recapitulate all the previous SDF-based experiments, but rather to serve as a proof of concept that a synthetic, minimized SDF peptide can retain the functional properties of native SDF, despite major conformational changes. From this initial success, future investigations will attempt to further refine the “ideal form” of a widely translatable SDF peptide using advanced computational techniques.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant 1R01HL089315-01 (to Y.J.W.), National Institutes of Health/Thoracic Surgery Foundation for Research and Education grant K08 HL072812 (to Y.J.W.), a Thoracic Surgery Foundation Research Award (to W.H.), and National Institutes of Health grant T32-HL-007843-13 (to W.H.).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DPBS

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- HPF

high-power field

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MNC

marrow mononuclear cell

- SDF

stromal cell-derived factor

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Bolognese L, Carrabba N, Parodi G, Santoro GM, Buonamici P, Cerisano G, et al. Impact of microvascular dysfunction on left ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcome after primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:1121–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118496.44135.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochitte CE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Reeder SB, McVeigh ER, Furuta T, et al. Magnitude and time course of microvascular obstruction and tissue injury after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;98:1006–14. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarantini G, Razzolini R, Cacciavillani L, Bilato C, Sarais C, Corbetti F, et al. Influence of transmurality, infarct size, and severe microvascular obstruction on left ventricular remodeling and function after primary coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heilmann C, Kostic C, Giannone B, Grawitz AB, Armbruster W, Lutter G, et al. Improvement of contractility accompanies angiogenesis rather than arteriogenesis in chronic myocardial ischemia. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atluri P, Liao GP, Panlilio CM, Hsu VM, Leskowitz MJ, Morine KJ, et al. Neovasculogenic therapy to augment perfusion and preserve viability in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1728–36. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo YJ, Grand TJ, Berry MF, Atluri P, Moise MA, Hsu VM, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor and granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor form a combined neovasculogenic therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuibban GA, Butler GS, Gong JH, Bendall L, Power C, Clark-Lewis I, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activity inactivates the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43503–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segers VF, Tokunou T, Higgins LJ, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Lee RT. Local delivery of protease-resistant stromal cell derived factor-1 for stem cell recruitment after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:1683–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.718718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X, Ma J, Jabbari E. Migration of marrow stromal cells in response to sustained release of stromal-derived factor-1alpha from poly(lactide ethylene oxide fumarate) hydrogels. Int J Pharm. 2010;390:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo J, Luo Z, Zhou N, Hall JW, Huang Z. Attachment of C-terminus of SDF-1 enhances the biological activity of its N-terminal peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:42–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonaros N, Sondermeijer H, Schuster M, Rauf R, Wang SF, Seki T, et al. CCR3-and CXCR4-mediated interactions regulate migration of CD34+ human bone marrow progenitors to ischemic myocardium and subsequent tissue repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1044–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruel M, Suuronen EJ, Song J, Kapila V, Gunning D, Waghray G, et al. Effects of off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting on function and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Wong S, Lafleche J, Crowe S, Mesana TG, Suuronen EJ, et al. In vitro functional comparison of therapeutically relevant human vasculogenic progenitor cells used for cardiac cell therapy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:216–24. 24e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1422–34. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo YJ, Panlilio CM, Cheng RK, Liao GP, Atluri P, Hsu VM, et al. Therapeutic delivery of cyclin A2 induces myocardial regeneration and enhances cardiac function in ischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I206–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo YJ, Panlilio CM, Cheng RK, Liao GP, Suarez EE, Atluri P, et al. Myocardial regeneration therapy for ischemic cardiomyopathy with cyclin A2. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:927–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu YH, Yang XP, Nass O, Sabbah HN, Peterson E, Carretero OA. Chronic heart failure induced by coronary artery ligation in Lewis inbred rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(2 Pt 2):H722–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jayasankar V, Bish LT, Pirolli TJ, Berry MF, Burdick J, Woo YJ. Local myocar-dial overexpression of growth hormone attenuates postinfarction remodeling and preserves cardiac function. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renault MA, Losordo DW. Therapeutic myocardial angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 2007;74:159–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De La Luz Sierra M, Yang F, Narazaki M, Salvucci O, Davis D, Yarchoan R, et al. Differential processing of stromal-derived factor-1alpha and stromal-derived factor-1beta explains functional diversity. Blood. 2004;103:2452–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillarisetti K, Gupta SK. Cloning and relative expression analysis of rat stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1)1: SDF-1 alpha mRNA is selectively induced in rat model of myocardial infarction. Inflammation. 2001;25:293–300. doi: 10.1023/a:1012808525370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi J, Kusano KF, Masuo O, Kawamoto A, Silver M, Murasawa S, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 effects on ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cell recruitment for ischemic neovascularization. Circulation. 2003;107:1322–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055313.77510.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohle R, Bautz F, Rafii S, Moore MA, Brugger W, Kanz L. The chemokine receptor CXCR-4 is expressed on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells and mediates transendothelial migration induced by stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 1998;91:4523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbott JD, Huang Y, Liu D, Hickey R, Krause DS, Giordano FJ. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a critical role in stem cell recruitment to the heart after myocardial infarction but is not sufficient to induce homing in the absence of injury. Circulation. 2004;110:3300–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147780.30124.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, et al. Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2003;362:697–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Wang J, Yang J, Kong X, Zheng F, Guo L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells over-expressing SDF-1 promote angiogenesis and improve heart function in experimental myocardial infarction in rats. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:644–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao T, Zhang D, Millard RW, Ashraf M, Wang Y. Stem cell homing and angiomyogenesis in transplanted hearts are enhanced by combined intramyocardial SDF-1alpha delivery and endogenous cytokine signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H976–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01134.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frederick JR, Fitzpatrick JR, McCormick RC, Harris DA, Kim AY, Muenzer JR, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α activation of tissue engineered endothelial progenitor cell matrix enhances ventricular function after myocardial infarction by inducing neovasculogenesis. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930404. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]