Abstract

Background

Maternal obesity is associated with unfavorable outcomes, which may be reflected in the as yet undiscovered gene expression profiles of the umbilical cord (UC).

Methods

UCs from 12 lean (pre-gravid BMI < 24.9) and 10 overweight/obese (OW/OB, pre-gravid BMI ≥25) women without gestational diabetes were collected for gene expression analysis using Human Primeview microarrays (Affymetrix). Metabolic parameters were assayed in mother’s plasma and cord blood.

Results

Although offspring birth weight and adiposity (at 2-wk) did not differ between groups, expression of 232 transcripts was affected in UC from OW/OB compared to those of lean mothers. GSEA analysis revealed an up-regulation of genes related to metabolism, stimulus and defense response and inhibitory to insulin signaling in the OW/OB group. We confirmed that EGR1, periostin, and FOSB mRNA expression was induced in UCs from OW/OB moms, while endothelin receptor B, KFL10, PEG3 and EGLN3 expression was decreased. Messenger RNA expression of EGR1, FOSB, MEST and SOCS1 were positively correlated (p<0.05) with mother’s first trimester body fat mass (%).

Conclusions

Our data suggest a positive association between maternal obesity and changes in UC gene expression profiles favoring inflammation and insulin resistance, potentially predisposing infants to develop metabolic dysfunction later on in life.

INTRODUCTION

Currently in the US, up to 60% of all pregnancies occur in women who are either overweight or obese at conception (1). This poses a significant public health concern as maternal obesity adversely affects the immediate health of both the mother and offspring (2,3). It is hypothesized that maternal obesity leads to developmental programming of excessive weight and adiposity in the offspring (4). Epidemiological and clinical studies (5,6) strongly support this hypothesis, including a recent study of 37,000 individuals that showed greater risk of cardiovascular disease and pre-mature death in those born to overweight and obese women (7). Also, findings from numerous animal models (8–11) show that maternal obesity and obesogenic diets program obesity risk in the offspring. Further support for developmental programming imprinted by maternal obesity comes from observations that children born to women following weight loss after bariatric surgery have diminished risk of obesity compared to children born to the same women prior to the surgery when they were obese (9,10). Recent studies confirm that weight loss in these obese women who then become pregnant is associated with changes in gene expression and DNA methylation of gluco-regulatory genes in the offspring (12). Despite these findings, markers indicative of metabolic programming remain yet to be identified.

Much of the mechanistic understanding of programming has come from animal models of gestational obesity. Using a rat model of overfeeding-induced obesity, we previously demonstrated that exposure to maternal obesity, from conception to birth, is sufficient to program increased obesity risk in the offspring (8,13–15). Offspring of obese dams are ‘hyper-responsive’ to high fat diets (HFD), gaining greater body weight, fat-mass and additional metabolic sequelae (8,14;15), including decreased fatty acid oxidation and impaired metabolic flexibility evident at weaning. These findings indicate that in a controlled model of maternal obesity, alterations in lipid metabolism and insulin signaling precede the development of obesity in offspring. However, the relevance of these mechanistic findings to human subjects remains unclear. One limitation to clinical studies is access to tissues from infants and offspring. However, recent studies have shown that the umbilical cord (UC) may be an easily accessible surrogate fetal tissue (16). Unlike the placenta, which is chimeric for both maternal and fetal compartments, the UC is purely fetal in nature, and is also likely influenced by factors in fetal circulation. Furthermore, studies in human subjects indicate that methylation status of specific CpG sites in the cord can be predictive of offspring adiposity (16,17). Nonetheless, no studies have examined global gene expression changes in the cord, which presumably could reveal important mechanisms relating to maternal obesity-associated fetal effects.

The present studies were designed to examine the hypothesis that the effect of maternal obesity on the fetus will be reflected by changes in UC gene expression profiles. Using microarrays, we characterized global gene expression in cord tissue from uncomplicated pregnancies in lean and obese women. First, we examined inflammatory mediators and insulin signaling gene expression in cord tissue from women who were obese at conception. Secondly, we conducted anthropometric and body composition assessments, in both the mother and infant, along with evaluation of metabolic and endocrine parameters normally dysregulated with the obese phenotype. To gain greater mechanistic insights, we also evaluated correlations between gene expression changes and maternal and fetal adiposity and endocrine parameters. Finally, we examined key pathways known to regulate insulin signaling in the cord and examined the contributions of circulating factors in cord blood (CB) in mediating UC gene expression changes in obesity. Our data strongly suggest that exposure to maternal obesity during fetal development, in the absence of gestational diabetes or any other pregnancy complications, alters fetal gene expression.

METHODS

Sample collection and processing

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) (NCT01131117) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. We studied participants enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study of lean and obese pregnant women and their term infants (the Glowing study) designed to investigate the effect of maternal obesity on offspring metabolism, adiposity and growth. For this report, umbilical cord (UC) and cord-blood (CB) were collected from 12 lean (pre-gravid BMI < 25kg/m2) and 10 overweight/obese (OW/OW, BMI ≥ 25kg/m2) mothers. All study visits were conducted at the Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center, UC and CB were collected at delivery in one of 5 local area hospitals. All subjects were either recruited pre-pregnancy or <10 wk of pregnancy and were second parity (because multi-parity is a risk factor for obesity) non-smoking mothers, without pre-existing or gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia or other pregnancy complications. Maternal body composition was assessed between 4–10 wk of pregnancy (Bodpod, Cosmed, Rome, Italy) and blood was collected at 30 wk of pregnancy for measurement of various metabolic parameters in plasma. Infant body composition was determined 2 wk after birth using Peapod (Cosmed). After collection, UCs were rinsed three times in phosphate buffered saline, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. While still frozen, the outer membrane of the UC was removed with a sterile blade, leaving UC arteries, vein and Wharton’s jelly. Venous CB was collected in heparinized tubes and cord plasma (CP) was isolated by centrifugation and stored at −70°C.

Metabolic and cytokine measurements in plasma

Insulin, leptin and interleukin (IL)-6 were measured in maternal and CP using ELISA (EMD Millipore Corporation, Boston, MA). Plasma glucose and triglycerides were assayed using colorimetric reagents (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) were quantitated with NEFA-C reagents (Wako Chemicals USA, Richmond, VA). HOMA-IR values were calculated using the HOMA Calculator (Diabetes trials unit, the University of Oxford)(18). Cytokine and metabolite measurements were performed in duplicate for all CP samples.

UC RNA isolation and microarray analysis

Total UC RNA was isolated from 100 mg of dissected cord tissue using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and purified using RNeasy Mini columns including DNase digestion (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). For gene expression profiling, individual microarrays (GeneChip Primeview Human Gene Expression Array, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were used for each UC sample. Briefly, 0.5 μg of purified RNA was used to synthesize cDNA. Biotin-labeled aRNA was synthesized from double-stranded cDNA using the GeneChip 3′ IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix). The wash and staining protocols were performed with GeneChip Scanner 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the probe arrays were scanned directly after hybridization.

Microarray data normalization and analysis

Microarray data analysis was carried out using GeneSpring v11 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). CEL files containing the probe level intensities were processed using the robust multi-array analysis (RMA) algorithm, for background adjustment, normalization, and log2-transformation of perfect match values. Subsequently the data were subjected to normalization by setting measurements less than 0.01 to 0.01 and by per-chip and per-gene normalization using GeneSpring normalization algorithms. The normalized data were used to generate lists of differentially expressed genes between UCs from lean and obese mothers. Genes were filtered based on minimum ±1.4-fold change (lean vs. OW/OB) and P-value ≤ 0.05 using Student’s t-test. A list of transcripts that were differentially expressed as a function of treatment was generated, and correlation-based hierarchical clustering between groups was performed. Enrichment of gene ontology (GO) terms for biological processes was performed using GeneSpring and GoRilla. Finally, gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was utilized to identify molecular functions and transcription factors enriched in UC from obese mothers. GSEA does not rely on an arbitrary cutoff (such as fold change between groups) and is a computational method that determines whether an a priori-defined set of genes shows statistically significant and concordant differences between two biological states.

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells (HUVSMCs) were purchased from Cell Applications (San Diego, CA), grown in Endothelial Cell Growth Medium or Smooth Muscle Growth Medium, respectively, and used between passages 2 to 8. Cells were switched to serum-free growth medium (Cell Applications, supplemented with 0.25% heat-inactivated bovine serum albumin) upon reaching ~80% confluency in 6-well plates, and treated with either lean or OW/OB CP (1%) for 48 hours. Pooled plasma from each group (lean and OW/OB) was utilized for cell treatment experiments. After 48 hours of treatment, HUVECs and HUVSMCs were washed once with PBS and then RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase treatment.

Real-time RT-PCR

One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA), and subsequent real-time PCR analysis was performed using the ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene specific primers were designed using Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems) for endothelin receptor B (EDNRB, Fwd: 5′- CAGATATCGAGCTGTTGCTTCTTG-3′, Rev: 5′- GAACCACAGAGACCACCCAAAT-3′), egl nine homolog 3 (C. elegans) (EGLN3, Fwd: 5′- AGAAAGGGCAGAAGCCAAAAAG-3′, Rev: 5′- AGAAAGGGCAGAAGCCAAAAAG-3′), early growth response 1 (EGR1, Fwd: 5′- AGGCCGAGATGCAGCTGAT-3′, Rev: 5′- CATCTCCTCCAGCTTAGGGTAGTT’3′), FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (FOSB, Fwd: 5′- GTCCTACGGAGCCTGCACTTT-3′, Rev: 5′- AACGTCCCGTTCCAACAATG-3′), Kruppel-like factor 10 (KLF10, Fwd: 5′- AATGAAAGCAGCCAGCATCCT-3′, Rev: 5′- CAGCGGCACATGGTATGTTCT-3′), mesoderm expression transcript (MEST, Fwd: 5′- CCATCCTCACACGACTGATGAA-3′, Rev: 5′- CATGTCCCACAGCTCACTCTCA-3′), neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 9 (NEDD9, Fwd: 5′- CTTATGGCAAGGGCCTTATATGA-3′, Rev: 5′- CCCCCTGTGTTCTGCTCTATG-3′), nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1, Fwd: 5′- AAGGCCGCTGTGCTGTGT-3′, Rev: 5′- GCACTGTGCGCTTGAAGAAG-3′), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1, Fwd: 5′- ATGTTCATTGCTGCCCCTTATG-3′, Rev: 5′- CTGGTCATGTTGCCTTTCCA-3′), phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1, Fwd: 5′- CTGGCTGGTTTTGGTTATGGAT-3′, Rev: 5′- GCATCTGTCCCGTAACCCTCTA-3′), paternally expressed 3 (PEG3, Fwd: 5′- GACCCTGATCAAACTCCGAAAC-3′, Rev: 5′- TCAGGTACTGCTCAAGGACCAA-3′), periostin (POSTN, Fwd: 5′- TGGAAGAGACGGTCACTTCACA-3′, Rev: 5′- AAGCCACTTTGTCTCCCATGAT-3′), suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1, Fwd: 5′- AGCTCCTTCCCCTTCCAGATT-3′, Rev: 5′- CCACATGGTTCCAGGCAAGTA-3′), signal recognition particle 14kDa (SRP14, Fwd: 5′- TGACGGAGCTGACCAGACTTT-3′, Rev: 5′- CTTCTTTGGAATGGGTTTGGTT-3′), and vascular endothelial growth factor α (VEGFα, Fwd: 5′- TCTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT-3′, Rev: 5′- GCGCTGATAGACATCCATGAAC-3′). The relative amounts of mRNA were quantified using a standard curve and normalized to the expression of human SRP14 mRNA.

Western blot analysis

Total cell and tissue lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40, 1.0% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA) containing 1mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting was carried out using standard procedures. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against pAkt, Akt, pErk1/2, and Erk1/2(Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and α-tubulin (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4°C. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies against rabbit and mouse IgG (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) were used for protein detection. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was performed using ImageJ software (v 1.47t, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Real-time RT-PCR data are expressed as mean fold change from lean ± SEM and western blot data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Because the data was normally distributed, correlations were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Statistical differences between UC from lean and OW/OB mothers were determined using a two-tailed student’s t test. In cases where three or more groups were compared, a one-way ANOVA followed by all-pair wise comparison by the Student-Neuman-Keuls method was performed. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (v 6.02, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Maternal obesity increases UC plasma leptin and insulin levels

A number of maternal anthropometric and metabolic parameters were measured before and during pregnancy (Table 1). As expected, there were significant differences in BMI (22.28 ± 0.46 vs 31.16 ± 1.11 kg/m2, P<0.001) and percent body fat (30.65 ± 0.91% vs 43.80 ± 1.36%, P<0.001) between lean and OW/OB subjects both prior to and after conception. Moreover, subjects in the OW/OB group continued to be heavier throughout pregnancy (P<0.001). As part of the study design, all participants (lean and OW/OB) were counseled to maintain weight-gain during pregnancy within Institute on Medicine (IOM) guidelines. Since IOM recommended weight gain for OW/OB women is lower than lean women, absolute gestational weight gain was significantly lower in OW/OB mothers (P<0.001) relative to lean counterparts. Fasting plasma insulin and leptin levels were significantly higher (2-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively) at 30 wk of gestation in OW/OB compared to lean mothers, while triglycerides and IL-6 were numerically greater in OW/OB mothers but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 1). OW/OB subjects showed greater insulin resistance, as assessed by HOMA-IR values (1.34 ± 0.2 vs. 2.03 ± 0.3, P=0.08). There were no differences in fasting glucose or NEFA concentrations between the groups.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and metabolic parameters of lean and overweight/obese (OW/OB) mothers

| Lean | OW/OB | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric parameters: | |||

| n | 12 | 10 | |

| Maternal age (years) | 31.0 ± 0.6 | 28.6 ± 0.7* | 0.021 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 22.28 ± 0.46 | 31.16 ± 1.11* | <0.001 |

| Body fat (%) at 4–10 weeks gestation | 30.65 ± 0.91 | 43.80 ± 1.36* | <0.001 |

| Weight at 36 weeks gestation (kg) | 73.63 ± 2.00 | 90.46 ± 3.36* | <0.001 |

| Gestational Weight gain (kg) | 13.23 ± 0.53 | 9.61 ± 0.81* | <0.001 |

| Gestational Length (weeks) | 38.9 ± 0.2 | 39.3 ± 0.3 | 0.394 |

|

| |||

| Plasma metabolic parameters: | |||

| Insulin (μU/mL, fasting) | 8.61 ± 1.67 | 16.47 ± 2.42* | 0.013 |

| Glucose (mg/dL, fasting) | 77.76 ± 1.28 | 78.51 ± 2.21 | 0.520 |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 13.44 ± 1.48 | 20.27 ± 2.43* | 0.022 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 95.50 ± 9.61 | 125.03 ± 25.95 | 0.267 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.67 ± 0.26 | 2.16 ± 0.24 | 0.184 |

| NEFAs (nmol/L) | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.487 |

Insulin, glucose, leptin, triglycerides, IL-6 and NEFAs were measured in mom’s plasma collected at 30 weeks gestation.

indicates a statistically significant difference between Lean and OW/OB mom groups (p<0.05).

Fetal anthropometric parameters and CP metabolic parameters were also measured (Table 2). There was no difference in birth weight, birth length or percent fat mass at 2 wk of age between offspring of lean and OW/OB mothers. However, CP leptin levels from OW/OB mothers were 2.2-fold higher (P≤ 0.02) than that of lean mothers. Also, CP insulin was ~1.5-fold higher in infants from OW/OB mothers compared to lean counterparts, though this difference did not attain statistical significance.

Table 2.

Anthropometric and metabolic parameters of offspring from lean and overweight/obese (OW/OB) mothers

| Lean mom | OW/OB mom | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric parameters: | |||

| n | 12 | 10 | |

| Baby’s gender (male/female) | 9/3 | 8/2 | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.65 ± 0.17 | 3.65 ± 0.12 | 0.987 |

| Birth length (cm) | 51.75 ± 0.90 | 51.05 ± 0.80 | 0.576 |

| Body mass at 2 weeks (kg) | 3.83 ± 0.15 | 3.82 ± 0.12 | 0.962 |

| Fat mass at 2 wks (%) | 13.24 ± 1.25 | 14.89 ± 1.22 | 0.361 |

| C-section (yes/no) | 6/6 | 4/6 | |

|

| |||

| Plasma metabolic parameters: | |||

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 5.81 ± 0.96 | 8.53 ± 1.62 | 0.150 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 64.52 ± 3.54 | 71.47 ± 3.77 | 0.196 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 2.89 ± 0.53 | 6.42 ± 1.38* | 0.027 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 24.96 ± 3.28 | 24.15 ± 4.72 | 0.887 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 8.88 ± 3.26 | 5.98 ± 2.24 | 0.500 |

| NEFAs (nmol/L) | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.574 |

Insulin, glucose, leptin, triglycerides, IL-6 and NEFAs were measured in umbilical cord plasma collected at the time of birth.

indicates a statistically significant difference between Lean and OW/OB mom groups (p<0.05).

Maternal obesity significantly alters gene expression in UC

Microarray analysis identified 232 differentially expressed genes in UC tissue (±1.4-fold change, P<0.05). Hierarchical clustering of microarray results is shown in Figure 1A–B. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of biological processes GO terms was performed with the list of differentially expressed genes and identified processes related to insulin receptor signaling, response to insulin stimulus, negative regulation of glucose import and transport and cellular response to fatty acids to be affected in UC tissue due to maternal obesity (Figure 1C). Gene set enrichment analysis for biological processes identified immediate/early transcription factors (EGR1, FOS, and FOSB), as well as genes involved in cytokine signaling (SOCS1) and Wnt/β-catenin signaling (MEST) to be upregulated in UC from OW/OB mothers, while genes related to vascular reactivity (EDNRB), angiogenesis (VEGFα), TGFβ signaling (KLF10), prolyl hydroxylase activity (EGLN3), tumor suppressor activity (PEG3) and Akt signaling (PDK1) were significantly downregulated in UCs from OW/OB mothers (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Maternal pre-gravid obesity significantly alters UC gene expression.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of (A) differentially expressed transcripts and (B) selected genes regulating tissue development, immediate-early response and inflammation in umbilical cord tissue of infants from lean and OW/OB mothers. (C) Enrichment of gene ontology biological process terms within differentially expressed genes in UC from lean compared to OW/OB mothers.

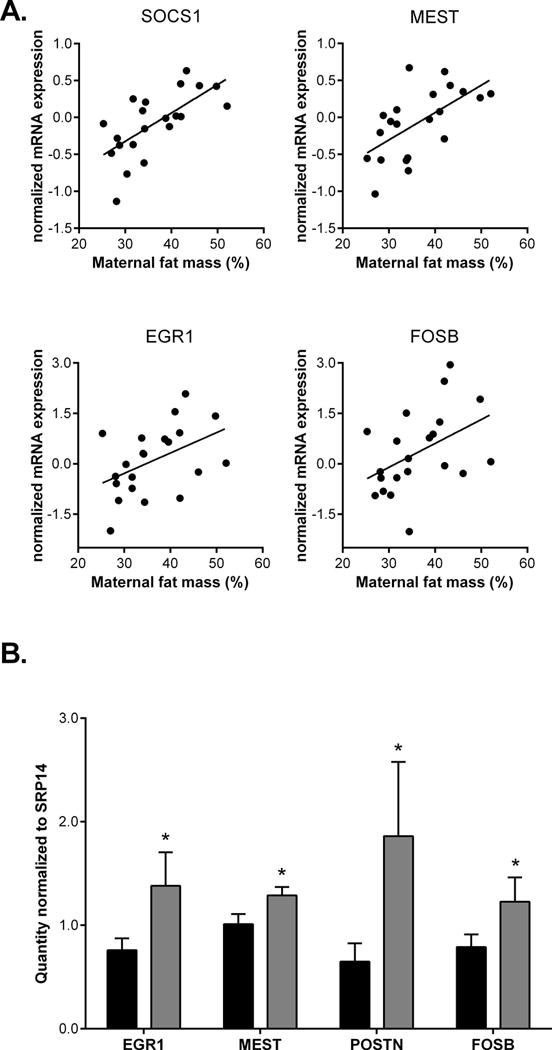

Maternal percent body fat correlates strongly with UC gene expression

To examine the relationship between maternal adiposity and UC gene expression, we carried out linear regression between these variables using the list of differentially expressed genes. Maternal pre-gravid percent body fat was positively correlated with transcript levels of SOCS1, MEST, EGR1 and FOSB (Figure 2A), and negatively correlated with transcript levels of KLF10 (Figure 3A) and PDK1 (r=−0.42, P=0.06, data not shown). Quantitative real-time PCR confirmed that mRNA expression of EGR1, POSTN (a cell adhesion molecule) and FOSB was significantly higher in UCs from OW/OB mothers compared to lean mothers (Figure 2B), while mRNA expression of EDNRB, KLF10, EGLN3, PEG3, PDK1 and VEGFα was significantly lower in UCs from OW/OB mothers (Figure 3B). Expression of PAI-1 (an inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator), NR4A1 (transcription factor involved in apoptosis) and NEDD9 (cytoskeletal adaptor molecule) tended to be higher in UCs from OW/OB mothers, though the difference between groups was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Figure 2. Maternal percent body fat positively correlates with MEST, SOCS1, EGR1, and FOSB expression.

(A) Correlation of maternal pre-gravid percent body fat with normalized UC microarray expression of MEST (r=0.61, P<0.01), SOCS1 (r=0.67, P<0.01), EGR1 (r=0.46, P=0.04) and FOSB (r=0.45, P=0.04). (B) Quantitative PCR confirmation of mRNA expression of EGR1, POSTN (periostin), and FOSB expression in UC from lean (black bars) and OW/OB mothers (gray bars). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of relative mRNA quantity normalized to SRP14 mRNA expression. * indicates P<0.05 between lean and OW/OB groups.

Figure 3. Maternal percent body fat negatively correlates with KLF10 and PDK1 expression.

(A) Correlation of maternal pre-gravid percent body fat with gene expression of KLF10 (r=−0.58, P<0.01). (B) Quantitative PCR confirmation of mRNA expression of EDNRB, KFL10, EGLN3, PEG3, PDK1 and VEGFα expression in UC from lean (black bars) and OW/OB mothers (gray bars). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of relative mRNA quantity normalized to SRP14 mRNA expression. * indicates P<0.05 between lean and OW/OB groups.

Maternal and CP plasma metabolic factors correlate with EGR1, FOSB, PDK1 and SOCS1 expression

We also carried out correlation analysis of UC gene expression with various maternal and CP metabolic factors. In the UC, expression of EGR1 and FOSB positively correlated with maternal fasting insulin (Figure 4A) and CP insulin levels (Figure 4C), while PDK1 negatively correlated with maternal insulin (Figure 4A) and CP insulin levels (Figure 4C). Expression of SOCS1 positively correlated with maternal leptin levels (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Maternal and cord plasma (CP) metabolic factors correlate with EGR1, FOSB, PDK1 and SOCS1 expression.

(A) Correlation of maternal plasma insulin levels at 30 weeks of pregnancy with gene expression of EGR1 (r=0.54, P=0.01), FOSB (r=0.60, P<0.01) and PDK1 (r=−0.55, P=0.01), (B) Correlation of maternal, fasted leptin levels at 30 weeks of pregnancy with gene expression of SOCS1 (r=0.61, P<0.01), (C) Correlation of CP insulin levels with gene expression of EGR1 (r=0.52, P=0.01), FOSB (r=0.52, P=0.02) and PDK1(r=−0.63, P<0.01).

Basal Akt activation, but not Erk1/2 activation is higher in UC from OW/OB mothers

Since CB leptin and insulin levels were higher in OW/OB mothers compared to lean mothers, we next examined the phosphorylation of Akt, a pathway common to both leptin and insulin signal transduction. Western blot analysis demonstrated that phosphorylated Akt (pAkt Ser473) levels were greater in UCs from OW/OB mothers. Likewise, when pAkt was normalized to total Akt, it was significantly higher in UC from OW/OB mothers compared to lean mothers (Figure 5A). Insulin also has mitogenic effects, via activation of Erk1/2. However, no differences were observed in pErk1/2 or total Erk1/2 expression in UCs between both groups (Figure 5A), suggesting that maternal obesity-associated changes specifically affect certain insulin signaling pathways.

Figure 5. Basal Akt phosphorylation is altered in UC from OW/OB mothers and cord plasma (CP) from OW/OB mothers alters endothelial cell gene expression.

(A) Western blot (right panel) and densometric analysis left panel of Akt and Erk proteins in UC lysates from lean and OW mothers. Black bars represent UC from lean mothers, while gray bars represent UC from OW/OB mothers. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of arbitrary densitometric values of pAkt/total Akt or pErk/total Erk. * indicates P<0.05 between lean and OW groups. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of EGR1 expression in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells (HUVSMCs) after treatment with cord blood (CB) from lean (black bars) and OW/OB mothers (gray bars). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of relative mRNA quantity normalized to SRP14 mRNA expression. * indicates P<0.05 between lean and OW groups.

CP from OW/OB mothers alters in vitro endothelial cell gene expression

Because the composition of UC plasma varied between lean and OW/OB mothers, we hypothesized that circulating factors in the CB plasma of offspring from OW/OB mothers could be driving changes in UC gene expression. Endothelial cells, the innermost layer of cells in blood vessels that are in direct contact with circulating blood, and smooth muscle cells of the umbilical blood vessels contribute largely to total RNA isolated from UCs. Thus, cultured HUVECs and HUVSMCs were used to study CB/blood vessel interactions. Akin to changes seen in vivo, EGR1 mRNA expression was significantly increased when HUVECs and HUVSMCs were cultured in the presence of CP from OW/OB mothers compared to CB plasma from lean mothers (Figure 5B).

DISCUSSION

The risk of obesity in adulthood is subject to programming in utero. Evidence from both experimental and clinical studies suggests that maternal obesity is an important determinant of weight gain and adiposity in offspring (4). In the current study, we leveraged microarray-based gene expression profiling to identify the major transcriptomic differences in umbilical cord (UC) tissue at term associated with maternal obesity. The UC offers several distinct advantages, including; being an easily accessible fetal tissue, and containing cell types relevant to developmental programming (endothelial, smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cells). To our knowledge, this is the first report to examine global gene expression in the UC. Several novel findings from the present study include: 1) maternal obesity alters global gene expression in the offspring at birth, despite no differences in birth weight, birth length and fat free mass in the offspring; 2) changes in the UC, specifically appear to be related to insulin and cytokine signaling, immediate/early transcription factors, angiogenesis and vascular reactivity; and 3) identification of specific genes that are associated with maternal fat mass. Furthermore, we also identified modulation of imprinted genes (MEST and PEG3) known to regulate fat mass and energy expenditure to be affected by maternal obesity. Our data suggest that gene expression profiles of infants born to overweight/obese women differ significantly from those of lean women, even in the absence of group differences in offspring body composition.

Obesity is associated with dysregulation of a number of metabolic pathways, most notably by the insulin signaling pathway (19). This is thought to be due in a large part to the chronic low-grade inflammation present both systemically and in insulin-sensitive tissues like the skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. As anticipated, maternal plasma insulin and HOMA-IR was higher in OW/OB mothers compared to lean mothers as expected, while fasting plasma glucose did not differ. While OW/OB women did not meet the clinical criteria of gestational diabetes, insulin resistance was evident. Consequently, CP insulin levels tended to be higher for infants of OW/OB mothers, compared to that of lean mothers. These effects did not attain statistical significance, possibly due to the small sample size. Nevertheless, the increase of CP insulin levels in OW mothers is consistent with a previous report in a larger cohort (53 lean and 68 obese participants), which considers more pronounced gestational obesity (2). Consistent with our findings, these researchers also observed that OW/OB mothers were more insulin resistant than lean mothers, and at birth, offspring from OW/OB mothers were insulin resistant compared to offspring from lean mothers. Since maternal insulin does not cross the blood/placental barrier (20), the fetal pancreas is the primary source of fetal insulin, suggesting that maternal obesity may be driving dysregulation of insulin signaling at birth.

Another important obesity-related peptide is leptin, which is a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in the regulation of food intake and energy balance, and is mainly produced in white adipose tissue and, to a lesser extent, in the placenta (21). Leptin levels correlate with adiposity and increase during the first two trimesters of pregnancy (21). Similar to insulin, leptin does not cross the blood/placental barrier (22), suggesting that CP leptin levels are indeed a marker of fetal adipocyte function. Maternal leptin levels in late pregnancy are positively correlated with infant birth weight (23), however higher CP leptin levels correspond with less weight gain in the first 6 months of life and lower BMI at age 3 (24). Not surprisingly, in our cohort, maternal leptin was significantly higher in OW/OB mothers compared to lean mothers. Interestingly, even though fat mass of 2 week-old offspring was not different between OW/OB and lean mothers, CP leptin levels were higher in offspring of OW/OB mothers which suggests that alterations in adipocyte function in offspring of OW mothers at birth. We also observed that UC mRNA expression of SOCS1, a protein downstream of inflammatory cytokine receptor activation, positively correlates with maternal fat mass and maternal leptin levels. SOCS1 expression is induced by both cytokines and insulin (25), and functions as a negative regulator of cytokine signal transduction. The correlation of SOCS1 expression with maternal leptin levels may reflect a fetal response to limit the actions of increased leptin and insulin signaling.

Chronic subclinical inflammation is an important recurring feature in obesity that affects insulin sensitivity. Studies in animal models of obesity and in pregnant women with obesity have clearly shown that a pro-inflammatory milieu extends to the maternal-fetal interface in the early peri-implantation period and in the placenta in late gestation. Likewise, maternal obesity in sheep and non-human primates has been shown to induce inflammation in the placenta, fetal liver, heart and intestine (26–28). The placenta in obese women is likewise characterized by inflammation and associated with increased systemic LPS levels (29–32). Our previous studies demonstrated activation of JNK and NF-κB pathways in placenta from obese women (33). Obesity is associated with several physiological changes (hyperinsulinemia, elevated acute phase proteins, sub-clinical endotoxemia) that could potentially contribute to placental inflammation. Also, in obese pregnancies it has been reported elevated levels of fatty acids and cytokines that induce pro-inflammatory responses in a variety of cellular contexts (29,34). Recently, we identified JNK/EGR-1 signaling as a key pathway through which lipotoxicity induces inflammation in placenta cells and in term placenta from obese women (33). Early growth response-1 is a pro-inflammatory transcription factor activated by numerous signals, including cytokines, hypoxia, growth factors and hormones (35). In the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome, insulin stimulates EGR1 expression and reduces insulin sensitivity by altering PI3K/Akt and Erk/MAPK signaling (36). In humans, EGR1 expression positively correlates with BMI and is highly expressed in adipocytes (37). Our report is the first to observe that UC EGR1 expression is strongly correlated with maternal fat mass, maternal insulin levels and fetal insulin levels, suggesting that maternal obesity per se drives the increases in maternal and fetal insulin, which in turn up-regulates EGR1 expression, and possibly contributing to alterations in fetal inflammatory markers and insulin sensitivity. Moreover, CP from OW/OB mothers increased EGR1 expression in endothelial and smooth muscle cell cultures, demonstrating the presence of factor(s) that can induce changes in gene expression in cells present in the umbilical cord. Interestingly, in mature adipocytes made insulin resistant with TNFα, a number of genes remained insulin-responsive, including EGR1 (38). Thus it is possible to envision that EGR1 transcriptional activity is maintained even in the face of elevated maternal and fetal insulin levels associated with maternal obesity.

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, we used a relatively small sample size. Nevertheless, we were able to identify significant differences in gene expression as a function of maternal body composition. Second, the validity of using the UC as a measure of offspring gene expression is not well established. However, recent reports suggest that the cord is a suitable surrogate for fetal tissue (16). While our results provide a unique snapshot of offspring gene expression at birth, it is unclear whether UC gene expression correlates with gene expression and function in metabolically important tissues such as liver, adipocytes and skeletal muscle. However, mesenchymal stem cells present in Wharton’s jelly of the umbilical cord are able to differentiate into all mesoderm-derived tissues, including the aforementioned metabolically relevant cell types (39,40). Further, recent studies have shown that methylation status of specific CpG sites in the cord can be predictive of offspring adiposity, suggesting that alterations in the cord may be reflective of meaningful changes in metabolic tissues. A third limitation is that we used UC samples that likely contained all cell types within the UC and thus we are unable to determine changes in gene expression for specific cell subtypes. Despite these limitations, the present study identifies specific mechanistic targets in offspring at birth that are affected by maternal obesity. We demonstrate that maternal obesity alters global gene expression in the offspring at birth, despite no differences in birth weight and fat free mass in the offspring, and these changes in UC gene expression specifically appear to be related to insulin and cytokine signaling, immediate/early transcription factors, angiogenesis and vascular reactivity. Lastly, we identified specific genes that are associated with maternal fat mass. Our findings suggest that maternal obesity is responsible for development changes that may contribute to the offspring’s risk of becoming obese and provide a starting point for identifying key pathways important in the development of obesity.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center-Human Studies Core for their assistance in these studies.

Statement of financial support: These studies were supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-ARS-CRIS 6251-51000-005-00D. Nursing support for these studies was provided in part by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute funded by the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program, Grants UL1-TR-000039and KL2-TR-000063. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Vahratian A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:268–73. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalano PM, Presley L, Minium J, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Fetuses of Obese Mothers Develop Insulin Resistance in Utero. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1076–80. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King JC. Maternal obesity, metabolism, and pregnancy outcomes. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:271–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalano PM. Obesity and pregnancy–the propagation of a viscous cycle? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3505–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J, Cianflone K, Biron S, et al. Effects of maternal surgical weight loss in mothers on intergenerational transmission of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4275–83. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1164–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds RM, Allan KM, Raja EA, et al. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and premature mortality from cardiovascular event in adult offspring: follow-up of 1 323 275 person years. BMJ. 2013;347:f4539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar K, Harrell A, Liu X, Gilchrist JM, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Maternal obesity at conception programs obesity in the offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R528–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00316.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCurdy CE, Bishop JM, Williams SM, et al. Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:323–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI32661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuelsson AM, Matthews PA, Argenton M, et al. Diet-induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring hyperphagia, adiposity, hypertension, and insulin resistance: a novel murine model of developmental programming. Hypertension. 2008;51:383–92. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White CL, Purpera MN, Morrison CD. Maternal obesity is necessary for programming effect of high-fat diet on offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1464–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenard F, Tchernof A, Deshaies Y, et al. Methylation and expression of immune and inflammatory genes in the offspring of bariatric bypass surgery patients. J Obes. 2013;2013:492170. doi: 10.1155/2013/492170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankar K, Zhong Y, Kang P, et al. Maternal obesity promotes a proinflammatory signature in rat uterus and blastocyst. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4158–70. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borengasser SJ, Lau F, Kang P, et al. Maternal obesity during gestation impairs fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial SIRT3 expression in rat offspring at weaning. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankar K, Kang P, Harrell A, et al. Maternal overweight programs insulin and adiponectin signaling in the offspring. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2577–89. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godfrey KM, Sheppard A, Gluckman PD, et al. Epigenetic gene promoter methylation at birth is associated with child’s later adiposity. Diabetes. 2011;60:1528–34. doi: 10.2337/db10-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gemma C, Sookoian S, Alvarinas J, et al. Maternal pregestational BMI is associated with methylation of the PPARGC1A promoter in newborns. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1032–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2191–2. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piya MK, McTernan PG, Kumar S. Adipokine inflammation and insulin resistance: the role of glucose, lipids and endotoxin. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:T1–15. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boskovic R, Feig DS, Derewlany L, Knie B, Portnoi G, Koren G. Transfer of insulin lispro across the human placenta: in vitro perfusion studies. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1390–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tessier DR, Ferraro ZM, Gruslin A. Role of leptin in pregnancy: consequences of maternal obesity. Placenta. 2013;34:205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepercq J, Challier JC, Guerre-Millo M, Cauzac M, Vidal H, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Prenatal leptin production: evidence that fetal adipose tissue produces leptin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2409–13. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Retnakaran R, Ye C, Hanley AJ, et al. Effect of maternal weight, adipokines, glucose intolerance and lipids on infant birth weight among women without gestational diabetes mellitus. CMAJ. 2012;184:1353–60. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantzoros CS, Rifas-Shiman SL, Williams CJ, Fargnoli JL, Kelesidis T, Gillman MW. Cord blood leptin and adiponectin as predictors of adiposity in children at 3 years of age: a prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:682–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard JK, Flier JS. Attenuation of leptin and insulin signaling by SOCS proteins. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu MJ, Du M, Nathanielsz PW, Ford SP. Maternal obesity up-regulates inflammatory signaling pathways and enhances cytokine expression in the mid-gestation sheep placenta. Placenta. 2010;31:387–91. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan X, Zhu MJ, Xu W, et al. Up-regulation of Toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappaB signaling is associated with enhanced adipogenesis and insulin resistance in fetal skeletal muscle of obese sheep at late gestation. Endocrinology. 2010;151:380–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Ma H, Tong C, et al. Overnutrition and maternal obesity in sheep pregnancy alter the JNK-IRS-1 signaling cascades and cardiac function in the fetal heart. FASEB J. 2010;24:2066–76. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-142315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu S, Haghiac M, Surace P, et al. Pregravid obesity associates with increased maternal endotoxemia and metabolic inflammation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:476–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Challier JC, Basu S, Bintein T, et al. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts KA, Riley SC, Reynolds RM, et al. Placental structure and inflammation in pregnancies associated with obesity. Placenta. 2011;32:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leibowitz KL, Moore RH, Ahima RS, et al. Maternal obesity associated with inflammation in their children. World J Pediatr. 2012;8:76–9. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saben J, Zhong Y, Gomez-Acevedo H, et al. Early growth response protein-1 mediates lipotoxicity-associated placental inflammation: role in maternal obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00076.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsay JE, Ferrell WR, Crawford L, Wallace AM, Greer IA, Sattar N. Maternal obesity is associated with dysregulation of metabolic, vascular, and inflammatory pathways. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4231–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLigio JT, Zorio DA. Early growth response 1 (EGR1): a gene with as many names as biological functions. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1889–92. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.20.9804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu X, Shen N, Zhang ML, et al. Egr-1 decreases adipocyte insulin sensitivity by tilting PI3K/Akt and MAPK signal balance in mice. EMBO J. 2011;30:3754–65. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Sun T, et al. Dietary obesity-induced Egr-1 in adipocytes facilitates energy storage via suppression of FOXC2. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1476. doi: 10.1038/srep01476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Expression profiling identifies genes that continue to respond to insulin in adipocytes made insulin-resistant by treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52298–306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim DW, Staples M, Shinozuka K, Pantcheva P, Kang SD, Borlongan CV. Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Phenotypic Characterization and Optimizing Their Therapeutic Potential for Clinical Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:11692–712. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anzalone R, Lo IM, Corrao S, et al. New emerging potentials for human Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells: immunological features and hepatocyte-like differentiative capacity. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:423–38. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]