Abstract

Pseudomonas putida is a Gram-negative soil bacterium which is well-known for its versatile lifestyle, controlled by a large repertoire of transcriptional regulators. Besides one- and two-component regulatory systems, the genome of P. putida reveals 19 extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors involved in the adaptation to changing environmental conditions. In this study, we demonstrate that knockout of extracytoplasmic function sigma factor ECF-10, encoded by open reading frame PP4553, resulted in 2- to 4-fold increased antibiotic resistance to quinolone, β-lactam, sulfonamide, and chloramphenicol antibiotics. In addition, the ECF-10 mutant exhibited enhanced formation of biofilms after 24 h of incubation. Transcriptome analysis using Illumina sequencing technology resulted in the detection of 12 genes differentially expressed (>2-fold) in the ECF-10 knockout mutant strain compared to their levels of expression in wild-type cells. Among the upregulated genes were ttgA, ttgB, and ttgC, which code for the major multidrug efflux pump TtgABC in P. putida KT2440. Investigation of an ECF-10 and ttgA double-knockout strain and a ttgABC-overexpressing strain demonstrated the involvement of efflux pump TtgABC in the stress resistance and biofilm formation phenotypes of the ECF-10 mutant strain, indicating a new role for this efflux pump beyond simple antibiotic resistance in P. putida KT2440.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas putida, a Gram-negative bacterium within the Gammaproteobacteria, is well-known for its versatile lifestyle, wide metabolic diversity, and high levels of resistance to toxic organic solvents (1). Consequently, its potential biotechnological application in a variety of different processes, including bioremediation of contaminated areas (2), biocatalysis of aromatic compounds (3), and production of bioplastics (4), or as an agent of plant growth promotion and plant pest control (5) is under investigation. In contrast, over the past decade P. putida has been identified to be an opportunistic human pathogen, causing difficult-to-treat nosocomial infections, such as bacteremia, in seriously ill patients (6). The majority of these infections are due to highly multidrug-resistant P. putida strains mostly found in immunocompromised humans, such as newborns or neutropenic or cancer patients (7, 8).

High levels of resistance to antibiotics or toxic organic solvents can be achieved by diverse mechanisms, including decreased uptake mediated by low outer membrane permeability and modification or degradation of the toxic substrate. However, one of the most efficient resistance mechanisms in pseudomonads is active efflux of these compounds by broadly specific efflux pump machineries, which are capable of exporting antimicrobial agents, such as antibiotics, biocides, detergents, and organic solvents (9). In general, these efflux systems can be divided into six classes, with the most relevant members belonging to the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family (10). RND-type multidrug efflux systems consist of an RND transporter protein, a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP), and an outer membrane factor (OMF) and have been described in various Gram-negative bacteria (11, 12). So far, the TtgABC, TtgDEF, and the TtgGHI efflux pumps have been characterized in more detail, and their involvement in solvent and antibiotic resistance in P. putida has been demonstrated (13–16).

The remarkable adaptability of P. putida, which allows this bacterium to colonize a variety of different environments, is driven at least in part by the sophisticated and coordinated gene expression mediated by a large repertoire of regulatory elements, including sigma factors. Sigma factors are subunits of the RNA polymerase and enable the specific binding to the respective promoter recognition sites (17). Hence, sigma factors are essential for prokaryotic transcription initiation and are divided into two main families, namely, σ70 and σ54 (18). Bacteria generally contain one major sigma factor, σ70, which is responsible for the transcription of a large set of genes involved in normal growth (19). In addition, most bacteria also possess a pool of alternative sigma factors, such as extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors, which are activated under a number of different growth conditions or in response to a variety of environmental stimuli, including membrane or cell wall stress, iron levels, and oxidation state (20). In comparison to other microorganisms, P. putida exhibits a striking number of 24 alternative sigma factors, with 19 of them being members of the ECF subfamily (17). The majority of these show high homologies to sigma factors known to play a role in iron acquisition; however, the function of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor ECF-10, which is encoded by open reading frame (ORF) PP4553 in P. putida KT2440, is still unknown.

In this study, we constructed a, ECF-10 knockout mutant in P. putida strain KT2440, characterized this mutant in more detail, and performed transcriptome analysis to identify the molecular basis of our observed phenotypes. Our results indicate that ECF-10 knockout causes overexpression of the major efflux pump TtgABC in P. putida KT2440, resulting in increased stress resistance and biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli was routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, and P. putida KT2440 was grown medium in M9 medium (21) with glucose as the sole carbon source. Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth was used for the determination of MICs. Bacteria were grown at 37°C for E. coli and 30°C for P. putida KT2440 with vigorous aeration. When required for plasmid or resistance gene selection and maintenance, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: for E. coli, ampicillin was added at 100 μg/ml and gentamicin was added at 10 μg/ml, and for P. putida KT2440, carbenicillin was added at 300 μg/ml and gentamicin was added at 30 μg/ml. For induction of the araBAD promoter in pJN105, 0.05 or 0.1% (wt/vol) l-arabinose was added to the medium.

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Description or sequencea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F− endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 λ− recA1 gyrA96 relA1 ϕ80dlacZΔM15 | Invitrogen |

| P. putida | ||

| KT2440 (wild type) | Wild-type P. putida KT2440 | DSM 6125 |

| ECF-10 | ECF-10 deletion mutant of P. putida KT2440 | This study |

| ECF-10+ | Complemented mutant P. putida KT2440 ECF-10 harboring plasmid pJN105::ECF-10 Gmr | This study |

| ttgABC+ | P. putida KT2440 Ampr Cbr overexpressing ttgABC | This study |

| ttgA | ttgA deletion mutant of P. putida KT2440 | 33 |

| ECF-10-ttgA | ECF-10 and ttgA deletion mutant of P. putida KT2440 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCP20 | Apr LacZα bla, Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vector | 59 |

| pJN105 | Gmr, arabinose-inducible araC-PBAD expression vector | 25 |

| pPS856 | Gmr, Gm resistance gene cassette | 23 |

| pEX18Ap | Ampr Cbr, gene replacement vector | 23 |

| pFLP3 | Flp expression vector | 24 |

| pUCP20::ECF-10 | EcoRI-HindIII ECF-10 in pUCP20, Ampr Cbr | This study |

| pUCP20::ECF-10ΩGm | EcoRI-HindIII ECF-10 with Gm resistance cassette from pPS856 in pUCP20 Ampr Cbr | This study |

| pEXAp::ECF-10ΩGm | ECF-10ΩGm in pEX18Ap Ampr | This study |

| pJN105::ECF-10 | EcoRI-XbaI ECF-10 in pJN105 Gmr | This study |

| pUCP20::ttgABC | Blunt-end ttgABC in pUCP20 Ampr Cbr | This study |

| Oligonucleotidesb | ||

| ECF-10-EcoRI-f | AAAAAGAATTCCGCTGGCAACGCGACGGTATCCC | |

| ECF-10-HindIII-r | AAAAAAAGCTTCATTCGATAGCCTGCAAACGCCG | |

| ECF-10-C-f | AAAAAGAATTCCGGGCCCATGAAGAAATG | |

| ECF-10-C-r | AAAAATCTAGACATTCGATAGCCTGCAAACGCCG | |

| ttgABC-f | AAAAATCTAGACCTGAGTACCACCCAGCAGT | |

| ttgABC-r | AAAAAAAGCTTGCGATAATCGAACGGAATGT | |

| qRT-PCR-PPrpoD-f | TGATCGACCTTGAGACCGAAA | |

| qRT-PCR-PPrpoD-r | CATCAGACCGATGTTGCCTTC | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1384-f | GCCTGGACTACTCGAAAATCCA | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1384-r | TGTCAATCCCGATGCGGTA | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1386-f | GTATCGGTCGCTCTTCGTTCAC | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1386-r | TTCCAGTACCAGCTGAACCGAG | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1387-f | TTCAACAACAAGGCCGAGCT | |

| qRT-PCR-PP1387-r | AACTCGCACTTGTGATGCAGG | |

| qRT-PCR-PP4553-f | CAAGGCGATTTGGTGGTTCTG | |

| qRT-PCR-PP4553-r | ATGGCCAATACCGCTGCAA |

Antibiotic resistance phenotypes: Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Cbr, carbenicillin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance. Sequences are 5′ → 3′.

f, forward; r, reverse.

Genetic manipulation.

Routine genetic manipulations were carried out using standard procedures (22). Primers were synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany) and are listed in Table 1. Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and DNA polymerases were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Dreieich, Germany). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a GeneJET plasmid miniprep kit, chromosomal DNA was isolated using a genomic DNA purification kit (Fermentas), and agarose gel fragments were isolated using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

Mutant strain and plasmid construction.

For the construction of an ECF-10 knockout mutant in P. putida KT2440, the ECF-10 gene was amplified by PCR and subsequently cloned into broad-host-range vector pUCP20, resulting in pUCP20::ECF-10. The knockout mutant was obtained according to the methods described previously (23). Briefly, plasmid pUCP20::ECF-10 was digested with PstI, and a Ω gentamicin resistance gene cassette was inserted into the PstI site of ECF-10, creating pUCP20::ECF-10ΩGm. To obtain the gene replacement vector, the disrupted ECF-10ΩGm was amplified via blunt-end PCR and inserted into the SmaI-linearized pEX18Ap suicide vector (23), and the vector was transferred into P. putida KT2440 by allelic exchange. The inserted gentamicin resistance cassette was removed by using plasmid pFLP3 (24), resulting in P. putida KT2440 ECF-10 (named ECF-10), and removal of the cassette was confirmed by PCR.

For the complementation experiments, the ECF-10 gene was amplified by PCR using EcoRI- and XbaI-flanked oligonucleotides and subsequently cloned colinearly into the l-arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter in pJN105 (25) to create pJN105::ECF-10. The plasmid was transferred into P. putida KT2440 ECF-10, resulting in P. putida KT2440 ECF-10/pJN105::ECF-10 (named ECF-10+), and the presence of the plasmid was confirmed by PCR.

For the construction of a double-knockout mutant in P. putida KT2440, the gene replacement vector pEX18Ap::ECF-10ΩGm was transferred into a P. putida KT2440 ttgA deletion mutant by allelic exchange. The inserted gentamicin cassette was removed by using plasmid pFLP3 (24), resulting in P. putida KT2440 ECF-10-ttgA (named ECF-10-ttgA), and removal of the cassette was confirmed by PCR.

For the overexpression of efflux pump TtgABC, the respective ttgABC genes were amplified by PCR; cloned colinearly to the lac promoter in broad-host-range vector pUCP20, resulting in pUCP20::ttgABC; and transferred into P. putida KT2440 (named ttgABC+).

Growth curves.

Bacterial cultures were grown overnight in LB broth and diluted in fresh LB broth, MH broth, or M9 minimal medium to obtain equal starting optical densities at 600 nm (OD600s) of 0.1. One hundred microliters of these cultures was added to 96-well microtiter plates. The growth of these cultures was monitored under various conditions, as indicated below, using a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro plate reader under shaking conditions. Two independent experiments were performed with three replicates for each strain.

Motility analysis.

Swimming and twitching motility were evaluated on LB medium plates at 30°C according to the methods described previously (26). For both the swimming and twitching assays, three independent experiments were performed with three replicates.

Biofilm assay.

The abiotic solid surface assay was used to measure biofilm formation according to a previously described method (27), with the following modifications. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in fresh M9 minimal medium, and the diluted cultures were inoculated into 96-well microtiter plates and incubated for 24 h at 30°C without shaking to allow bacterial adherence and biofilm formation. After incubation, the biofilm cells were stained using 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet, and the absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro microtiter plate reader. All experiments were done in triplicate with 6 individual repeats per measurement (n = 18).

MIC determination.

The MICs of different antibiotics were determined in MH broth as described previously (28, 29). For the strains with the l-arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter, 0.05% l-arabinose was added to the culture medium.

Killing curves.

Killing curves were performed as described before (30) in MH broth, with some modifications. Cells of an overnight culture were inoculated in fresh medium and grown at 30°C to mid-logarithmic growth phase under shaking conditions. Antibiotics were added at 10-fold the MIC, aliquots were taken at different time points, serial dilutions were plated on LB agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. Individual cell colonies were counted, and the number of CFU per milliliter was determined.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from the wild-type and mutant strains, which were grown in LB broth to logarithmic growth phase (OD600 = 1.3) at 30°C, using RNeasy Midi columns (Qiagen), followed by RNAprotect cell reagent (Qiagen) treatment and subsequent centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 min. DNase treatment of isolated RNA samples, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) in an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) were performed as described previously (21, 31). All reactions were normalized to the reaction for the housekeeping gene rpoD. Experiments were performed three times each with bacteria from two independent cultures.

Transcriptome analysis.

Cultures of the P. putida wild type and ECF-10 mutant were incubated at 30°C until they reached exponential growth phase. Extraction of total RNA and DNase treatment were performed as described above. Enrichment of mRNA and, therefore, depletion of rRNA were accomplished with a MICROBExpress bacterial mRNA enrichment kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sequencing libraries were generated from 50 ng of rRNA-depleted RNA samples following the Truseq RNA protocol (Illumina). Paired end reads (two sets of 50 nucleotides each) were obtained with a HiSeq 1000 system using SBS (v3) kits (Illumina). Cluster detection and base calling were performed using RTA software (v1.13), and the quality of the reads was assessed with the CASAVA (v1.8.1) program (Illumina).

The sequencing resulted in 48.2 million and 47.5 million pairs of 50-nucleotide-long reads for the wild type and the knockout mutant, respectively, with a mean Phred quality score of >35. The reads were mapped against the genome of P. putida KT2440 (GenBank accession number NC_002947) using the bowtie program (32). Gene expression was determined by counting for each gene the number of reads that overlapped with the annotation location. The genomic annotation of P. putida KT2440 was downloaded from the Pseudomonas genome database (www.pseudomonas.com) (33). Differential expression was calculated using the R package DESeq (34), and genes were assumed to be differentially expressed if the change in expression was at least ±2-fold and the P value was less than 0.05.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Complete expression data are deposited at the Sequence Read Archive (NCBI) under accession number SRP034542.

RESULTS

ECF-10 deletion results in enhanced resistance to heat, oxidative stress, and antibiotics.

Previously, open reading frame PP4553 was identified to be an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor in P. putida KT2440 belonging to the ECF subfamily within the σ70 family and named ECF-10 (17). Computational operon prediction suggests that ECF-10 forms a putative chromosomal gene cluster with three hypothetical ORFs (PP4554 to PP4556) located upstream (33, 35). None of these ORFs exhibits any homology to anti-sigma factors or other characterized proteins.

In the first instance, we analyzed if ECF-10 is expressed under normal laboratory growth conditions, using quantitative real-time PCR of RNA samples obtained from cells grown in M9 medium at 30°C with shaking and harvested at lag (3 h of growth), exponential (8 h), early stationary (16 h), and late stationary (24 h) phases. The gene expression profiles of cells collected after 8, 16, and 24 h were compared with those of cells collected at lag phase (3 h). Overall, these analyses revealed that ECF-10 is expressed under all tested conditions, with rates of expression being 4.4 ± 0.38 times higher at 8 h of incubation, 3.3 ± 0.67 times higher at 16 h of incubation, and 1.9 ± 0.63 times higher at 24 h of incubation relative to the level of expression at 3 h (lag phase).

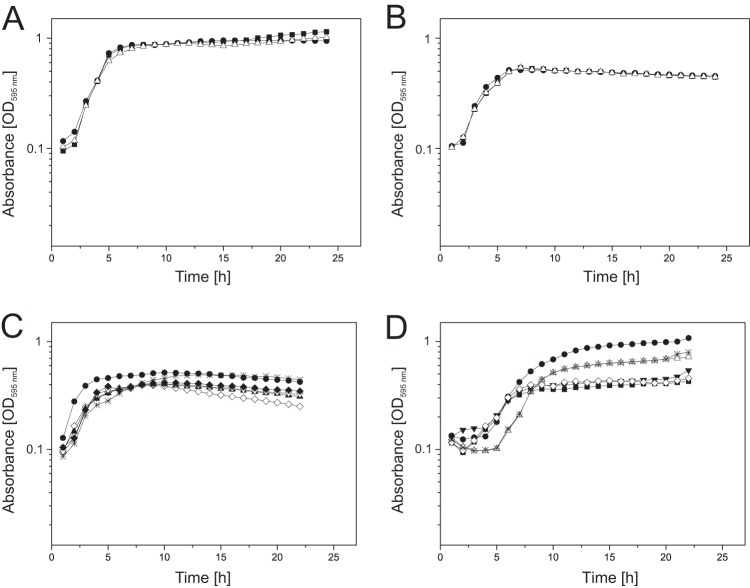

To investigate the role of ECF-10 in P. putida, we constructed a site-directed ECF-10 knockout mutant in P. putida KT2440. No significant differences in the growth of the P. putida KT2440 wild type and ECF-10 mutant were observed when cells were grown in LB or M9 minimal medium at 30°C (Fig. 1A and B) under shaking conditions. Since ECF sigma factors are known to play an important role in the transcriptional response to extracytoplasmic stress (17), we performed growth analyses under conditions of oxidative, osmotic, and heat stress as well as under conditions of phosphate, magnesium, and nitrogen limitation. Growth of the ECF-10 mutant was unaffected during phosphate, magnesium, and nitrogen starvation and in the presence of 0.5 M sodium chloride (data not shown). In contrast, the ECF-10 mutant showed a moderate increase in growth at 42°C (Fig. 1C) and a significant increase in growth under oxidative stress conditions in the presence of 0.1% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Growth of the P. putida KT2440 wild type (closed squares), ECF-10 mutant (closed circles), complemented mutant ECF-10+ (open triangles), ttgA (closed inverted triangles), ECF-10-ttgA (open diamonds), and ttgABC+ (asterisks) strains at 30°C in LB broth (A), in M9 minimal medium (B), under heat stress at 42°C in LB broth (C), and with 0.1% (vol/vol) H2O2 in LB broth (D).

Since recent studies have demonstrated a role for ECF sigma factors in antibiotic resistance (36, 37), we investigated the impact of the ECF-10 sigma factor knockout on the susceptibility of P. putida KT2440 to different classes of antibiotics. As shown in Table 2, the ECF-10 mutant exhibited a 2- to 4-fold increase in resistance to ciprofloxacin, meropenem, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, and sulfamethoxazole compared to that of the wild-type strain. No changes in the susceptibility of the ECF-10 mutant to imipenem and tobramycin were observed. For complementation experiments, ECF-10 was cloned colinearly into pJN105 under the control of an arabinose-dependent araBAD promoter, resulting in hybrid plasmid pJN105::ECF-10. First attempts using an inductor concentration of 0.1% (wt/vol) arabinose resulted in variable complementation of the mutant (data not shown). However, using a concentration of 0.05% (wt/vol) arabinose, which resulted in more moderate ECF-10 gene expression, this altered resistance phenotype could be complemented by heterologous expression of the cloned ECF-10 gene in strain ECF-10+ (Table 2). Quantitative real-time PCR revealed 2-fold higher levels of ECF-10 gene expression in the presence of 0.1% (wt/vol) arabinose than in the presence of a concentration of 0.05% (wt/vol) in the complemented strain ECF-10+ (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

MICs of different antibiotics

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | MER | CM | NA | SX | IMP | TOB | |

| Wild type | 0.03 | 0.03 | 16 | 4 | 64 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| ECF-10 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 32 | 16 | 128 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| ECF-10+ | 0.03 | 0.03 | 16 | 4 | 64 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| ttgA | 0.015 | 0.015 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.06 |

| ECF-10-ttgA | 0.015 | 0.015 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.06 |

Results are the modes from 6 independent experiments. CIP, ciprofloxacin; MER, meropenem; CM, chloramphenicol; NA, nalidixic acid; SX, sulfamethoxazole; IMP, imipenem; TOB, tobramycin.

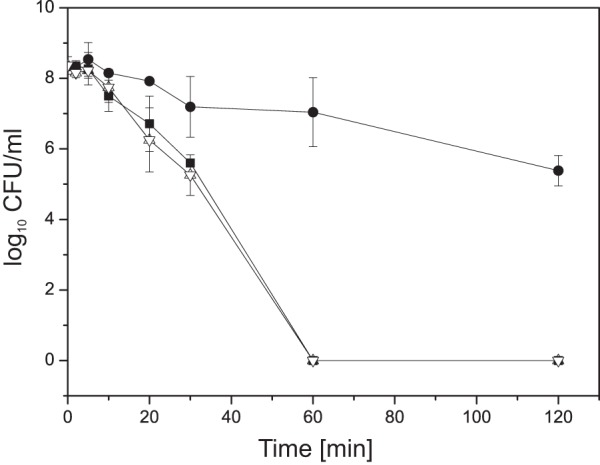

To verify these results, we carried out killing curves and examined wild-type and mutant cells for their sensitivity to antibiotic killing. While no viable wild-type cells were detected after 1 h of incubation with 0.3 μg/ml ciprofloxacin (10× MIC), the ECF-10 mutant strain exhibited increased resistance, with a decrease in the numbers of CFU of less than 2 log orders being detected after 1 h of incubation. This resistance phenotype could be complemented back to wild-type susceptibility by introducing wild-type copies of ECF-10 (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Time-kill assay for the P. putida KT2440 wild type (closed squares), ECF-10 mutant (closed circles), and complemented mutant ECF-10+ (open inverted triangles). The strains were incubated at 30°C for the indicated times after addition of 0.3 μg/ml ciprofloxacin (10× MIC), and the numbers of CFU ml−1 (in log units) of surviving cells were counted. The data are from three independent experiments.

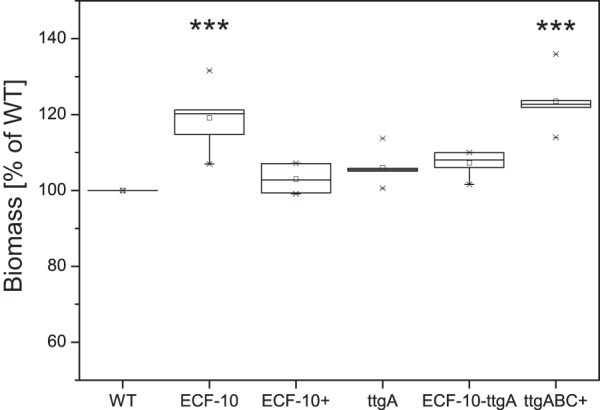

Inactivation of ECF-10 impacts biofilm formation.

The formation of resistant biofilms is an important stress response and survival strategy of bacteria. To analyze the ability of the ECF-10 mutant to develop biofilms, we carried out static microtiter biofilm assays to demonstrate that the ECF-10 mutant displayed a statistically significant 20% increase in biomass after 24 h of incubation at 30°C in comparison to that of the parent strain (Fig. 3). Since bacterial motility has a strong impact on initial bacterial adhesion and subsequent biofilm development, we analyzed flagellum-mediated swimming and type IV pilus-mediated twitching motility to show that the ECF-10 mutant did not reveal any alteration in motility compared to that of wild-type cells (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Enhanced biofilm formation of the ECF-10 mutant in static biofilm assays. Cells were grown for 24 h at 30°C in polystyrene microtiter plates in M9 medium. The box plots (the line in each box is the median) represent the means of 3 independent biological repeats assayed 6 times each (n = 18). ***, a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) between strains ECF-10 and ttgABC+ and the wild type (WT), determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

Gene expression profiling.

To determine the molecular basis for the observed ECF-10 mutant phenotypes, transcriptome analysis was performed using deep cDNA sequencing, and the expression profile of the ECF-10 mutant was compared to that of the wild type after growth to mid-logarithmic phase in LB medium. This analysis identified a total set of 12 genes that were significantly (P < 0.05) dysregulated more than 2-fold, with 7 being upregulated genes and 5 being downregulated genes in the mutant strain relative to their expression in the wild type (Table 3). These results were verified by independent qRT-PCR analysis of three genes (PP1384, PP1386, and PP1387 in Table 3) and provided validation for our sequencing data. Most strikingly, we observed the significant upregulation of the ttgA (PP1386), ttgB (PP1385), and ttgC (PP1384) genes, which code for an efflux pump belonging to the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family. In addition, ttgR, the regulator of the ttgABC operon, was also significantly upregulated, as was the downstream-located gene PP1388, which exhibits high degrees of homology to the EmrB/QacA family of drug resistance transporters. This observed upregulation of a major RND efflux system is consistent with the antibiotic resistance phenotype of the ECF-10 mutant that was noticed. Among the genes that were downregulated, which indicated positive regulation by ECF-10, were PP5329 (pstS) and PP3244 (mgtC), which exhibit homologies to genes involved in phosphate and magnesium transport, respectively. However, detailed analyses of the expression profile of genes dysregulated less than 2-fold did not reveal any further statistically significant downregulated genes related to phosphate or magnesium transport. Since these results indicated a dysregulation in magnesium and phosphate transport, we performed growth analyses of the wild-type and mutant strains in the presence of phosphate and magnesium at various concentrations; however, no growth defect could be detected (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Illumina sequencing results indicating genes significantly dysregulateda in the ECF-10 mutant compared to wild-type P. putida KT2440

| Locus tag | Gene name | Fold change | P value | Product name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP1384b | ttgC | 2.94 | 3.12E−12 | NodT family RND efflux system outer membrane lipoprotein |

| PP1385 | ttgB | 4.17 | 9.96E−21 | Hydrophobe/amphiphile efflux-1 (HAE1) family transporter |

| PP1386b | ttgA | 5.90 | 6.26E−29 | RND family efflux transporter MFP subunit |

| PP1387b | ttgR | 3.58 | 1.27E−13 | TetR family transcriptional regulator |

| PP1388 | 2.48 | 2.93E−05 | EmrB/QacA family drug resistance transporter | |

| PP2441 | 3.96 | 1.48E−12 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PP2658 | −2.00 | 1.74E−04 | Phosphate ABC transporter permease | |

| PP3244 | −2.12 | 3.47E−04 | Magnesium transporter MgtC family protein | |

| PP3274 | phaI | −2.81 | 3.30E−02 | Phenylacetate coenzyme A oxygenase/reductase subunit PaaK |

| PP3278 | paaA | −2.85 | 1.76E−03 | Phenylacetate coenzyme A oxygenase subunit PaaA |

| PP3881 | 2.14 | 2.31E−04 | Phage terminase, large subunit | |

| PP5329 | −2.09 | 1.47E−06 | Phosphate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein |

Significant dysregulation was considered differential expression of ≥2-fold.

Differential expression was verified by independent qRT-PCR analysis.

Efflux pump activity impacts antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation.

Since the gene expression analysis revealed an upregulation of genes coding for the TtgABC efflux pump, we constructed the ECF-10-ttgA mutant with a double knockout of ECF-10 and ttgA as well as the ttgABC-overexpressing strain ttgABC+ to investigate the role of this efflux pump in stress resistance and formation of biofilms. The inactivation of the TtgABC efflux pump in the double mutant ECF-10-ttgA resulted in an increase in susceptibility to the tested antibiotics ciprofloxacin, meropenem, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, and sulfamethoxazole, a profile which was identical to the antibiotic resistance profile of a ttgA single mutant, suggesting that TtgABC-related efflux is the basis for enhanced antibiotic resistance in the ECF-10 mutant strain (Table 2).

Moreover, initial biofilm experiments in the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor phenyl-arginine-β-naphthylamidine (PAβN; final concentration, 10 μg/ml) demonstrated that both the wild type and the ECF-10 mutant strain had an identical ability to form biofilms (data not shown), suggesting that overexpression of the efflux pump TtgABC might be the basis for the increased biofilm formation in the ECF-10 mutant strain. To verify these results, we analyzed the biofilms of the ECF-10-ttgA and ttgABC+ strains to demonstrate that TtgABC indeed plays a role in other adaptation processes in P. putida KT2440, such as biofilm formation, which are beyond simple antibiotic resistance. The overexpression of ttgABC in P. putida KT2440 resulted in the enhancement of biofilm formation by approximately 25%, which was in a range similar to that for the biofilm formation phenotype of the ECF-10 knockout mutant (Fig. 3). In addition, knockout of TtgABC in the double mutant ECF-10-ttgA could restore the biofilm formation phenotype back to wild-type levels, underlining a role for ttgABC overexpression in the increase in biofilm formation.

Furthermore, growth analyses at 42°C revealed a higher density of ttgABC+ cells than wild-type cells, which was comparable to the growth behavior of ECF-10, suggesting a possible explanation for the increased growth of ECF-10 under heat stress (Fig. 1C). Additional growth analyses in the presence of hydrogen peroxide also suggested an involvement of the TtgABC efflux pump in the oxidative stress resistance of KT2440, since cells of ttgABC+ demonstrated higher densities than wild-type cells (Fig. 1D). However, since a TtgABC knockout in ECF-10-ttgA could not completely restore growth to wild-type levels, other factors may also be involved in the oxidative stress resistance of ECF-10.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of extracytoplasmic sigma factor ECF-10 in the stress resistance and biofilm formation of P. putida KT2440. An isogenic knockout mutant of ECF-10 was constructed, and the respective mutant showed increased antibiotic, heat, and oxidative stress resistance as well as enhanced biofilm formation. Gene expression analyses and follow-up experiments revealed the upregulation of efflux pump TtgABC in the ECF-10 mutant to be responsible for the observed resistance and biofilm formation phenotypes.

In addition to one-component and two-component regulatory systems, extracytoplasmic function sigma factors represent the third most abundant principle of bacterial signaling networks allowing bacteria to adapt to diverse environmental and often stressful conditions (38). Thus, ECFs play an important role in connecting extracellular stimuli to an appropriate cellular response by binding to a characteristic promoter site and thereby recruiting the associated RNA polymerase to the specific promoter. P. putida KT2440 exhibits an extraordinarily high number of ECF sigma factors, with 19, in comparison to other microorganisms, like Staphylococcus aureus or Escherichia coli, which possess only 2 and 7 ECFs, respectively (17). This complex sigma factor signaling network in P. putida is in accordance with the strong ability of this organism to trigger adaptive responses to a wide variety of different environmental changes (17). So far, sigma factors have been associated with various and highly diverse cellular processes in P. putida KT2440, such as carbon and nitrogen metabolism (39), motility (40), polyhydroxyalkanoate production (41), or root-plant colonization (42), among many others.

Of these 19 ECFs identified in P. putida KT2440, 13 are described to play a potential role in iron metabolism, since they exhibit similarities to the E. coli FecI sigma factor, which is involved in iron acquisition (17). However, sequence analyses of ECF-10 as well as our transcriptome studies did not reveal any association of ECF-10 with iron metabolism. The subset of genes which showed altered levels of expression of more than 2-fold in the ECF-10 knockout mutant was relatively small, with 12 such genes being detected under our test conditions. The most striking dysregulation was the increased expression of genes coding for the ttgABC efflux pump. TtgABC belongs to the RND family of efflux systems, which has been identified in all major kingdoms and plays an important role in resistance to various antimicrobial agents, toxins, or heavy metals (10). Thus far, three efflux pumps, namely, TtgABC, TtgDEF, and TtgGHI, have been identified and characterized in more detail in strains P. putida KT2440 and P. putida DOT-T1E (13–16). It has been shown that TtgABC is a broad-spectrum efflux pump essential for antibiotic resistance in P. putida KT2440 and P. putida DOT-T1E and is involved in the extrusion of several different classes of antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, and chloramphenicol, among others (9, 43, 44). Earlier studies have demonstrated that ttgABC is expressed at moderate basal levels in P. putida DOT-T1E (15) and that expression of ttgABC is increased from 3- to 4-fold in response to some antibiotics, like chloramphenicol and tetracycline (9). Thus, our observed upregulation of expression of the ttgABC cluster in the ECF-10 knockout mutant is in agreement with its increased antibiotic resistance phenotype, which was demonstrated by MIC and killing curve assays. In addition, construction and analyses of the double-knockout mutant ECF-10-ttgA underline our findings and clearly demonstrate the role of TtgABC in the ECF-10 antibiotic resistance phenotype.

In addition to ttgABC, we also obtained an increase in expression of the ttgR gene, which is located directly upstream of ttgA and codes for the respective negative regulator of this efflux pump cluster (9, 45, 46). TtgR is a homodimeric drug binding repressor that is able to bind to a palindromic operator site which overlaps both ttgABC and ttgR promoters and dissociates from it in the presence of some antibiotics (9). In this way, TtgR controls the expression of ttgABC as well as ttgR itself, and it has been shown that the patterns of expression of the ttgA and ttgR promoters were almost identical (9). Interestingly, TtgR is a repressor which is able to bind to structurally different antibiotics, resulting in the dissociation of TtgR from its respective promoter sites and the subsequent induction of both ttgR and ttgABC expression in response to these antimicrobial agents (9).

Biofilms represent a common microbial life strategy, allowing bacteria to stay in a protected environment and survive even harsh conditions (47). The biofilm matrix displays a barrier that confers tolerance against various antimicrobial agents as well as the host immune response (48, 49). Furthermore, biofilms cause undesirable fouling, e.g., of membrane bioreactor systems for water treatment, significantly reducing the efficiency of the purification system (50). The formation and development of biofilms are highly complex adaptation processes influenced by a large repertoire of proteins and factors. Since our RNA sequencing results indicated the upregulation of the TtgABC efflux pump to be one possible molecular basis for the alterations in biofilm development in the ECF-10 mutant strain, we investigated the influence of TtgABC on the biofilm formation of P. putida KT2440. By construction and subsequent characterization of the double-knockout mutant ECF-10-ttgA as well as the ttgABC-overexpressing strain ttgABC+, we were able to show that the formation of biofilms is indeed influenced by the efflux pump TtgABC in P. putida KT2440. Both the ECF-10 mutant and strain ttgABC+ exhibited an increase in biomass of approximately 25% after 24 h of incubation. In contrast, inactivation of TtgABC in the ECF-10 mutant restored biofilm formation back to wild-type levels. This connection of efflux pump activity and biofilm development has also been described previously for other bacteria, including E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella enterica (51, 52), and the inhibitory effect of efflux pump inhibitors on biofilm formation was demonstrated. However, little is still known about the precise mechanism and contribution of multidrug efflux pumps in the development of bacterial biofilms and other adaptation and stress responses. In this context, we also observed the possible involvement of TtgABC in the adaptation to heat and oxidative stress in P. putida KT2440, since the ECF-10 mutant as well as the ttgABC-overexpressing strain exhibited elevated cell densities in comparison to the wild type. The involvement of efflux pumps in such adaptation processes has been described in earlier studies; for example, the MacAB efflux pump plays a role in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species in S. enterica (53).

To get a first insight into the mechanism of how ECF-10 might impact ttgABC expression, we analyzed the levels of ttgA gene expression in the complemented strain ECF-10+ (which overexpresses ECF-10 by its inducible arabinose promoter) relative to those in the wild type and showed that ttgA is expressed to a similar extent in ECF-10+, and the levels were not statistically significantly different between the two strains (data not shown). These results indicate that induced overexpression of ECF-10 does not result in a reduction of ttgABC expression in comparison to that in the wild type, suggesting that ECF-10 might not be a direct negative regulator or repressor of ttgABC. One other possible explanation for the altered ttgABC gene expression in the ECF-10 knockout mutant could be sigma factor competition for the core RNA polymerase. This phenomenon has been shown to be responsible for altered regulation of genes or even whole pathways in various bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli, among many others (54, 55). Although the ECF sigma factor RpoT (ECF-12) was identified to control the ttgGHI efflux pump genes in P. putida DOT-T1E (56), so far, no sigma factor has been described to be involved in ttgABC transcription. If, indeed, ECF-10 competed with a different sigma factor which is normally used for ttgABC expression, the overexpression of ECF-10 might have resulted in a more evident reduction of ttgABC expression. Further studies are needed to clarify the precise role of ECF-10 in ttgABC gene expression, for example, by the determination of ECF-10 binding sites using chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (57).

Overall, we were able to demonstrate that inactivation of the ECF-10 sigma factor impacts stress resistance and biofilm formation in P. putida KT2440 by affecting expression of the genes for the major efflux pump TtgABC. A deeper understanding of adaptation processes and resistance mechanisms in P. putida KT2440 will help to optimize the biotechnological potential of this bacterium in the fields of agriculture, bioremediation, and biocatalysis and in the production of bioplastics (58). Further investigations will focus on the precise contribution of TtgABC in stress adaptation and the characterization of the ECF-10 signaling network, e.g., by identification of its activation mechanism and environmental stimuli and analysis of binding motifs and DNA interaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the BioInterfaces (BIF) program of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in the Helmholtz Association and by the Concept for the Future of KIT.

We thank Victor de Lorenzo for kindly providing strains and plasmids.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Pieper DH, Martins dos Santos VA, Golyshin PN. 2004. Genomic and mechanistic insights into the biodegradation of organic pollutants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15:215–224. 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dejonghe W, Boon N, Seghers D, Top EM, Verstraete W. 2001. Bioaugmentation of soils by increasing microbial richness: missing links. Environ. Microbiol. 3:649–657. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaggenborg R, Overhage J, Steinbüchel A, Priefert H. 2003. Functional analyses of genes involved in the metabolism of ferulic acid in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61:528–535. 10.1007/s00253-003-1260-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivera ER, Carnicero D, Garcia B, Minambres B, Moreno MA, Canedo L, Dirusso CC, Naharro G, Luengo JM. 2001. Two different pathways are involved in the beta-oxidation of n-alkanoic and n-phenylalkanoic acids in Pseudomonas putida U: genetic studies and biotechnological applications. Mol. Microbiol. 39:863–874. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh UF, Morrissey JP, O'Gara F. 2001. Pseudomonas for biocontrol of phytopathogens: from functional genomics to commercial exploitation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:289–295. 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00212-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SE, Park SH, Park HB, Park KH, Kim SH, Jung SI, Shin JH, Jang HC, Kang SJ. 2012. Nosocomial Pseudomonas putida bacteremia: high rates of carbapenem resistance and mortality. Chonnam Med. J. 48:91–95. 10.4068/cmj.2012.48.2.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trevino M, Moldes L, Hernandez M, Martinez-Lamas L, Garcia-Riestra C, Regueiro BJ. 2010. Nosocomial infection by VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas putida. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:853–855. 10.1099/jmm.0.018036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombardi G, Luzzaro F, Docquier JD, Riccio ML, Perilli M, Coli A, Amicosante G, Rossolini GM, Toniolo A. 2002. Nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas putida producing VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4051–4055. 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4051-4055.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teran W, Felipe A, Segura A, Rojas A, Ramos JL, Gallegos MT. 2003. Antibiotic-dependent induction of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E TtgABC efflux pump is mediated by the drug binding repressor TtgR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3067–3072. 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3067-3072.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng TT, Gratwick KS, Kollman J, Park D, Nies DH, Goffeau A, Saier MH., Jr 1999. The RND permease superfamily: an ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:107–125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zgurskaya HI, Nikaido H. 2000. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 37:219–225. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweizer HP. 2003. Efflux as a mechanism of resistance to antimicrobials in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related bacteria: unanswered questions. Genet. Mol. Res. 2:48–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramos JL, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. 1998. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 180:3323–3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosqueda G, Ramos JL. 2000. A set of genes encoding a second toluene efflux system in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E is linked to the tod genes for toluene metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 182:937–943. 10.1128/JB.182.4.937-943.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duque E, Segura A, Mosqueda G, Ramos JL. 2001. Global and cognate regulators control the expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1100–1106. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rojas A, Duque E, Mosqueda G, Golden G, Hurtado A, Ramos JL, Segura A. 2001. Three efflux pumps are required to provide efficient tolerance to toluene in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 183:3967–3973. 10.1128/JB.183.13.3967-3973.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Bueno MA, Tobes R, Rey M, Ramos JL. 2002. Detection of multiple extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors in the genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and their counterparts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01. Environ. Microbiol. 4:842–855. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bashyam MD, Hasnain SE. 2004. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factors: role in bacterial pathogenesis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 4:301–308. 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potvin E, Sanschagrin F, Levesque RC. 2008. Sigma factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:38–55. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho TD, Ellermeier CD. 2012. Extra cytoplasmic function sigma factor activation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15:182–188. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breidenstein EB, Janot L, Strehmel J, Fernandez L, Taylor PK, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Gellatly SL, Levesque RC, Overhage J, Hancock RE. 2012. The Lon protease is essential for full virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 7:e49123. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dymecki SM. 1996. A modular set of Flp, FRT and lacZ fusion vectors for manipulating genes by site-specific recombination. Gene 171:197–201. 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00035-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman JR, Fuqua C. 1999. Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the l-arabinose-inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene 227:197–203. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00601-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marr AK, Overhage J, Bains M, Hancock RE. 2007. The Lon protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is induced by aminoglycosides and is involved in biofilm formation and motility. Microbiology 153:474–482. 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002519-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman L, Kolter R. 2004. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 51:675–690. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03877.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. 2008. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 3:163–175. 10.1038/nprot.2007.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Mah TF. 2008. Involvement of a novel efflux system in biofilm-specific resistance to antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 190:4447–4452. 10.1128/JB.01655-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapple DS, Hussain R, Joannou CL, Hancock RE, Odell E, Evans RW, Siligardi G. 2004. Structure and association of human lactoferrin peptides with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2190–2198. 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2190-2198.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neidig A, Yeung AT, Rosay T, Tettmann B, Strempel N, Rueger M, Lesouhaitier O, Overhage J. 2013. TypA is involved in virulence, antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 13:77. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winsor GL, Van Rossum T, Lo R, Khaira B, Whiteside MD, Hancock RE, Brinkman FS. 2009. Pseudomonas Genome Database: facilitating user-friendly, comprehensive comparisons of microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D483–D488. 10.1093/nar/gkn861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anders S, Huber W. 2010. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao F, Dam P, Chou J, Olman V, Xu Y. 2009. DOOR: a database for prokaryotic operons. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D459–D463. 10.1093/nar/gkn757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HY, Chen CC, Fang CS, Hsieh YT, Lin MH, Shu JC. 2011. Vancomycin activates σB in vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resulting in the enhancement of cytotoxicity. PLoS One 6:e24472. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo Y, Helmann JD. 2012. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σM in beta-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol. Microbiol. 83:623–639. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07953.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascher T. 2013. Signaling diversity and evolution of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16:148–155. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cases I, Ussery DW, de Lorenzo V. 2003. The σ54 regulon (sigmulon) of Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 5:1281–1293. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osterberg S, Skarfstad E, Shingler V. 2010. The sigma-factor FliA, ppGpp and DksA coordinate transcriptional control of the aer2 gene of Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1439–1451. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmann N, Rehm BH. 2004. Regulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237:1–7. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Gil M, Yousef-Coronado F, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2010. LapF, the second largest Pseudomonas putida protein, contributes to plant root colonization and determines biofilm architecture. Mol. Microbiol. 77:549–561. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Garcia E, de Lorenzo V. 2011. Engineering multiple genomic deletions in Gram-negative bacteria: analysis of the multi-resistant antibiotic profile of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 13:2702–2716. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez M, Conde S, de la Torre J, Molina-Santiago C, Ramos JL, Duque E. 2012. Mechanisms of resistance to chloramphenicol in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1001–1009. 10.1128/AAC.05398-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daniels C, Daddaoua A, Lu D, Zhang X, Ramos JL. 2010. Domain cross-talk during effector binding to the multidrug binding TTGR regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 285:21372–21381. 10.1074/jbc.M110.113282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teran W, Krell T, Ramos JL, Gallegos MT. 2006. Effector-repressor interactions, binding of a single effector molecule to the operator-bound TtgR homodimer mediates derepression. J. Biol. Chem. 281:7102–7109. 10.1074/jbc.M511095200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dueholm MS, Sondergaard MT, Nilsson M, Christiansen G, Stensballe A, Overgaard MT, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T, Otzen DE, Nielsen PH. 2013. Expression of Fap amyloids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. fluorescens, and P. putida results in aggregation and increased biofilm formation. Microbiologyopen 2:365–382. 10.1002/mbo3.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovacs AT, van Gestel J, Kuipers OP. 2012. The protective layer of biofilm: a repellent function for a new class of amphiphilic proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 85:8–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen PO, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C. 2010. The immune system vs. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 59:292–305. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chao Y, Zhang T. 2011. Growth behaviors of bacteria in biofouling cake layer in a dead-end microfiltration system. Bioresour. Technol. 102:1549–1555. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.08.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kvist M, Hancock V, Klemm P. 2008. Inactivation of efflux pumps abolishes bacterial biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7376–7382. 10.1128/AEM.01310-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baugh S, Ekanayaka AS, Piddock LJ, Webber MA. 2012. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:2409–2417. 10.1093/jac/dks228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bogomolnaya LM, Andrews KD, Talamantes M, Maple A, Ragoza Y, Vazquez-Torres A, Andrews-Polymenis H. 2013. The ABC-type efflux pump MacAB protects Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from oxidative stress. mBio 4(6):e00630-13. 10.1128/mBio.00630-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin Y, Withers TR, Wang X, Yu HD. 2013. Evidence for sigma factor competition in the regulation of alginate production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 8:e72329. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Vos D, Bruggeman FJ, Westerhoff HV, Bakker BM. 2011. How molecular competition influences fluxes in gene expression networks. PLoS One 6:e28494. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duque E, Rodriguez-Herva JJ, de la Torre J, Dominguez-Cuevas P, Munoz-Rojas J, Ramos JL. 2007. The RpoT regulon of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E and its role in stress endurance against solvents. J. Bacteriol. 189:207–219. 10.1128/JB.00950-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones CJ, Newsom D, Kelly B, Irie Y, Jennings LK, Xu B, Limoli DH, Harrison JJ, Parsek MR, White P, Wozniak DJ. 2014. ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq reveal an AmrZ-mediated mechanism for cyclic di-GMP synthesis and biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003984. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moreno R, Rojo F. 2013. The contribution of proteomics to the unveiling of the survival strategies used by Pseudomonas putida in changing and hostile environments. Proteomics 13:2822–2830. 10.1002/pmic.201200503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.West SE, Schweizer HP, Dall C, Sample AK, Runyen-Janecky LJ. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81–86. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]