Abstract

We previously identified two small-molecule CD4 mimetics—NBD-556 and NBD-557—and synthesized a series of NBD compounds that resulted in improved neutralization activity in a single-cycle HIV-1 infectivity assay. For the current investigation, we selected several of the most active compounds and assessed their antiviral activity on a panel of 53 reference HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses representing diverse clades of clinical isolates. The selected compounds inhibited tested clades with low-micromolar potencies. Mechanism studies indicated that they act as CD4 agonists, a potentially unfavorable therapeutic trait, in that they can bind to the gp120 envelope glycoprotein and initiate a similar physiological response as CD4. However, one of the compounds, NBD-09027, exhibited reduced agonist properties, in both functional and biophysical studies. To understand the binding mode of these inhibitors, we first generated HIV-1-resistant mutants, assessed their behavior with NBD compounds, and determined the X-ray structures of two inhibitors, NBD-09027 and NBD-10007, in complex with the HIV-1 gp120 core at ∼2-Å resolution. Both studies confirmed that the NBD compounds bind similarly to NBD-556 and NBD-557 by inserting their hydrophobic groups into the Phe43 cavity of gp120. The basic nitrogen of the piperidine ring is located in close proximity to D368 of gp120 but it does not form any H-bond or salt bridge, a likely explanation for their nonoptimal antagonist properties. The results reveal the structural and biological character of the NBD series of CD4 mimetics and identify ways to reduce their agonist properties and convert them to antagonists.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most critical events in the HIV infection process is entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into target cells; this is, therefore, considered an important target for developing antiviral drugs (1–3). Already, approval of two HIV-1 entry inhibitor drugs, enfuvirtide (Fuzeone; T-20) (4) and maraviroc (Selzentry) (5, 6), has validated entry prevention as a successful strategy in antiviral drug design. Entry of the HIV-1 type is initiated by binding of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 to the primary cell surface receptor CD4; this induces the conformational changes to gp120 necessary for its subsequent binding to the cellular coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4. Binding of gp120 to the coreceptor is responsible for additional conformational changes to the envelope, as it activates envelope glycoprotein gp41 to a fusion-active stage for subsequent fusion of the viral and cell membrane and, eventually, entry of the virus into cells to initiate infection. The X-ray structures of gp120 bound to CD4 and a Fab fragment of the neutralizing antibody 17b expose a large cavity (800 Å2) within gp120 that is formed by conserved residues (7). One of the major hydrophobic interaction residues in CD4 is Phe43, which deeply penetrates inside the cavity of gp120, a location referred to as the Phe43 cavity and is designated the binding site of gp120. This highly conserved and functionally important cavity is sufficiently large to accommodate a small-molecule inhibitor which can plug into it and prevent CD4 from binding; consequently, this cavity represents a very attractive target for drug design.

Considerable attempts have been made to target the gp120 binding site for drug development, starting with soluble CD4 (sCD4). Although sCD4 exhibited remarkable activity in vitro (8, 9), it failed in clinical trials to be effective at clinically relevant dose levels in HIV-1-infected individuals (10). Based on the sCD4 success in vitro, attempts were made to construct CD4 mimics, and they resulted in high-affinity peptide-based inhibitors, such as the CD4M33 miniprotein (11). This miniprotein, which binds to gp120 with high affinity and elicits very potent HIV-1 inhibitory activity, clearly demonstrated that the Phe43 cavity is a valid target for developing HIV-1 entry inhibitors. In 2003, Lin et al. reported the discovery of BMS-378806, a highly potent small-molecule compound that initially was claimed to target the Phe43 cavity (12). Later, however, it was conclusively proven (13) that this compound does not bind to the Phe43 cavity. In 2005, using the targeted screening approach of chemical libraries, we identified two test compounds—NBD-556 and NBD-557—that were capable of preventing syncytia in a cell-cell fusion assay (14). The compounds also inhibited a panel of laboratory-adapted and primary isolates with low-micromolar potency, a discovery that led to additional studies from several research groups (15–27) that uncovered the binding mechanism of these small-molecule inhibitors and their subsequent effect on the conformation of gp120. The binding of these molecules to the Phe43 cavity was confirmed in biophysical and resistant mutant studies (24, 25, 27); other studies also have shown that these compounds of only about 337 Da in size are capable of inducing conformational changes in gp120 (24, 25). Collectively, these studies prompted renewed interest in synthesizing newer analogs to uncover more potent inhibitors against this target (24, 26, 27). Progress toward this goal has, unfortunately, been hampered by the nonavailability of either unbound gp120 structures or any gp120-bound small-molecule structures. In 2012, we reported the structure of NBD-556 in complex with the core structure of gp120 and Fab of the monoclonal antibody (MAb) 48D (28). The structures of additional NBD-type compounds in complex with the gp120 core likewise have been reported recently (20, 22, 23). We anticipated that this structural information would improve our understanding of the details of the ligand binding that causes conformational changes in gp120 and, thereby, help us to design more effective analogs of these inhibitors.

The NBD-556-bound gp120 structure did in fact reveal that the 4-chlorophenyl ring of the molecule deeply penetrated inside the Phe43 cavity; however, the 2,2′,6,6′-tetramethylpiperidine ring was located outside the cavity and so made no major contribution to binding. Moving forward, and utilizing the X-ray structure information, we designed inhibitors by replacing the 2,2′,6,6′-tetramethylpiperidine moiety of NBD-556 with scaffolds that had the potential to interact with the critical binding site residues in gp120, and we synthesized a set of new molecules. Several of these compounds displayed much-improved antiviral activitiy in a single-cycle infection assay (29).

In this report, we describe the systematic study of the antiviral potency of a selected set of NBD compounds (Fig. 1) against a panel of 53 HIV-1 Env-pseudotyped viruses representing subtypes A, A/D, A2/D, A/E, A/G, B, C, and D. We also delineate the binding modes of these agonists in the HIV-1 envelope gp120 by developing a drug-induced resistance study and determining the X-ray structures of two of the inhibitors in complex with the gp120 core. We expect that the structural, mechanistic, and resistance mutation information will facilitate further development of these inhibitors as HIV-1 therapeutics and microbicides.

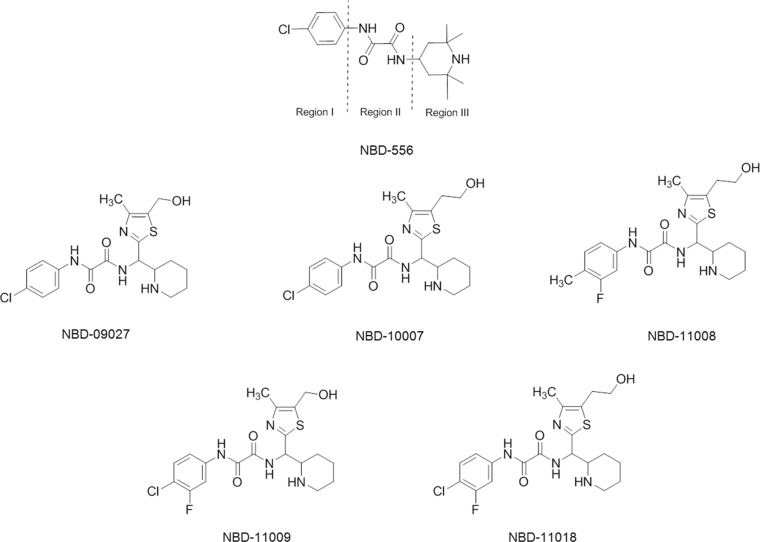

FIG 1.

Chemical structures of NBD series compounds. The locations of regions I, II, and III are shown for NBD-556.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

MT-2 cells (human T-cell leukemia cells) were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARP) from D. Richman, and H9/HTLV-/HIV-1IIIB cells (obtained through the NIH ARP from R. Gallo) and Jurkat cells (obtained through the NIH ARP from A. Weiss) (30) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/μl each).

TZM-bl cells (a HeLa cell line that expresses CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 and also luciferase and β-galactosidase under the control of the HIV-1 promoter; obtained from J. C. Kappes, X. Wu, and Tranzyme Inc. [now Ocera Therapeutics, Inc.], San Diego, CA) through the NIH ARP (31, 32), HEK 293T cells (ATCC), and Cf2Th/CD4-CCR5 and Cf2Th-CCR5 cells (kindly provided by J. G. Sodroski [33]) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin.

U87-CD4-CCR5 and U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells (obtained through the ARP from H. Deng and D. R. Littman [34]) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 1 μg/ml puromycin, 300 μg/ml G418, penicillin, and streptomycin. The ACTOne cell line ACTOne-CXCR4 (a modified HEK 293T cell line, purchased from Codex BioSolutions, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), expressing coreceptor CXCR4 without CD4, was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, G418, puromycin, penicillin, and streptomycin.

The Env expression vector pSVIIIenv-ADA and mutant pSVIIIenv-ADA-N197S DNA were kindly provided by J. G. Sodroski of Harvard (33). The HIV-1 Env molecular clone expression vector pHXB2-env (X4) DNA was obtained through the ARP from K. Page and D. Littman (35). HIV-1 Env molecular clones of gp160 genes for HIV-1 Env pseudovirus production were obtained as follows. Clones representing the standard panels A, A/D, A2/D, and D and panel C (QB099.391M.ENV.B1 and QB099.391M.ENV.C8) were obtained through the NIH ARP from J. Overbaugh (36, 37). The HIV-1 Env molecular clones of subtypes A/G and A/E were obtained through the NIH ARP from D. Ellenberger, B. Li, M. Callahan, and S. Butera (38). The HIV-1 Env molecular clones of standard reference subtype B were obtained through the NIH ARP from D. Montefiori, F. Gao, and M. Li (6535, clone 3 [SVPB5]; PVO, clone 4 [SVPB11]; TRO, clone 11 [SVPB12]; AC10.0, clone 29 [SVPB13]; QH0692, clone 42 [SVPB6]; SC422661, clone B [SVPB8]). B. H. Hahn and J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez provided pREJO4541 clone 67 (SVPB16), pRHPA4259 clone 7 (SVPB14), and pWITO4160 clone 33 (SVPB18). B. H. Hahn and D. L. Kothe provided pTHRO4156 clone 18 (SVPB15) and pCAAN5342 clone A2 (SVPB19) (32, 39, 40). Subtype B pWEAUd15.410.5017 and p1058_11.B11.1550 were obtained through the NIH ARP from B. H. Hahn, B. F. Keele, and G. M. Shaw (41). The subtype C HIV-1 reference panel of Env clones was also obtained through the NIH ARP from D. Montefiori, F. Gao, S. A. Karim, and G. Ramjee (Du 156.12 and Du172.17); D. Montefiori, F. Gao, C. Williamson, and S. A. Karim (Du422.1); B. H. Hahn, Y. Li, and J.F. Salazar-Gonzalez (ZM197M.PB7, ZM233M.PB6, ZM249M.PL1, and ZM214M.PL15); E. Hunter and C. Derdeyn (ZM53M.PB12, ZM135M.PL10a, and ZM109F.PB4); and L. Morris, K. Mlisana, and D. Montefiori (CAP45.2.00.G3 and CAP210.2.00.E8) (42–44).

The Env-pseudotyped genes of BG505.T332N, KNH1144, and B41 were kindly provided by J. P. Moore of the Weill Cornell Medical College, NY. The Env-deleted proviral backbone plasmids pNL4-3.Luc.R-.E- DNA (N. Landau [45, 46]) and pSG3Δenv DNA (J. C. Kappes and X. Wu [32, 40]) were obtained through the NIH ARP. The full-length, replication, and infection-competent chimeric DNA pNL4-3 was obtained through the NIH ARP from M. Martin (47). The DNA fragment encoding Rev-gp160 was subcloned from the YU2 strain. The expression vector was constructed as previously described (48). Env-expressing vectors pVPack-VSV-G and pVPack-Ampho, a murine leukemia virus (MLV) Gag-Pol-expressing vector pVPack-GP, and a pFB-luc vector were obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA).

sCD4 was purchased from ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc. (Woburn, MA), and the 17b hybridoma was kindly provided by J. Robinson of Tulane University, New Orleans, LA.

Pseudovirus preparation.

We prepared pseudoviruses capable of single-cycle infection as previously described (29). Briefly, 5 × 106 HEK 293T cells were plated in a T75 flask 24 h before transfection. Cells were transfected in 15 ml of medium with a mixture of 10 μg of an Env-deleted proviral backbone plasmid, pNL4-3.Luc.R.E DNA or pSG3Δenv DNA, and 10 μg of an Env expression vector by using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Amphotropic MLV (A-MLV) pseudovirus was prepared by transfecting 293T cells with a mixture of 10 μg each of the Env-expressing vector pVPack-Ampho, the MLV Gag-Pol-expressing vector pVPack-GP, and a pFB-Luc vector by using FuGENE 6. The G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) pseudovirus was prepared as described above, with a mixture of 10 μg each of the Env-expressing vector pVPack–VSV-G, the pVPack-GP Gag-Pol-expressing vector, and the pFB-Luc vector. Pseudovirus-containing supernatants were collected 2 days after transfection and then filtered and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Pseudovirus titers were determined to identify the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) by infecting the different cell types. Cells were plated in 96-well plates 24 h before infection. On the day of the infection, 100-μl aliquots of serial 2-fold dilutions of pseudoviruses were added to the cells. After 3 days of incubation, the cells were washed 2 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with 50 μl of the cell culture lysis reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). The lysates were transferred to a white 96-well plate (Costar) and mixed with 100 μl of a luciferase assay reagent (Luciferase assay system; Promega). We immediately measured the luciferase activity with a Tecan infinite M1000 reader (Tecan, San Jose, CA). We scored wells producing relative luminescence unit (RLU) levels that were 4 times the background as positive. We calculated the TCID50 according to the Spearman-Karber statistical method.

Cell-cell fusion.

To detect HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion, we performed a dye transfer assay as previously described (49). H9/HIV-1IIIB cells that express fusion proteins on their surface and continuously produce large amounts of virus were labeled with Calcein-AM, a fluorescent reagent (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) for 30 min at 37°C, washed 2 times with PBS, and then incubated with MT-2 cells (ratio, 1:10) in 96-well plates at 37°C for 3 h in the presence or absence of compounds (NBD-09027, -10007, -11008, -11009, -11018, and -556). We then counted the fused and unfused calcein-labeled HIV-1-infected cells with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) fitted with an eyepiece micrometer disc. To calculate the percent inhibition of cell-cell fusion and the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s), we used Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Note that we use IC50 throughout the manuscript because the compounds described here act at the cell surface and uptake/metabolism does not affect the IC50s.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurement of CD4-gp120 binding.

We coated high-binding 96-well enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoassay plates (Costar) with 100 μl of the sheep anti-gp120 antibody D7324 (Aalto Bio Reagents Ltd., Dublin, Ireland) at 2 μg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated them at 4°C overnight before blocking with 2% nonfat milk in PBS at 37°C for 1 h. Recombinant HIV-1IIIB gp120 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc.) at 0.5 μg/ml in PBS was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. sCD4 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc.) at 0.25 μg/ml was then added in the presence of an equal volume of one of the test compounds at different concentrations at 37°C for 1 h, followed by rabbit anti-sCD4 IgG (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc.) at 0.25 μg/ml in PBS. To that mixture was added, sequentially, biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase, and tetramethylbenzidine. Following termination of the reactions, we recorded absorbance at 450 nm in a Tecan Infinite M1000 reader. We calculated the percent inhibition and the IC50s by using GraphPad Prism software.

Infectivity assay against CD4-dependent and CD4-independent viruses. (i) R5-tropic viruses.

For infectivity assays with R5-tropic viruses, we seeded CD4-expressing cells, Cf2Th/CD4-CCR5, and CD4-negative cells, Cf2Th-CCR5, at 6 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well tissue culture plate and cultured them overnight at 37°C. The Cf2Th/CD4-CCR5 cells were infected with the recombinant HIV-1 expressing luciferase and pseudotyped with the envelope glycoprotein from HIV-1 ADA, which utilizes CCR5 as coreceptor (NL4-3-ADA-Luc). The CD4-negative Cf2Th-CCR5 cells were infected with CD4-independent recombinant HIV-1 expressing luciferase, pseudotyped with the N197S mutant ADA envelope (NL4-3-ADA-N197S-Luc) and NL4-3-ADA-Luc, as previously reported (50). Briefly, we mixed 50 μl of a test compound at graded concentrations with an equal volume of the respective recombinant virus. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the mixtures were added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and lysed with 40 μl of cell culture lysis reagent. Lysates were transferred to a white 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent. We measured the luciferase activity immediately, as described above, to obtain the percent inhibition with respect to the control and calculated the IC50s, again using GraphPad Prism software.

(ii) X4-tropic viruses.

For infectivity assays with X4-tropic viruses, we plated CD4-negative ACTOne-CXCR4 cells at 104 cells/well in a 96-well tissue culture plate and cultured them at 37°C overnight. The cells were infected with HXB2-Env-mutated pseudoviruses expressing luciferase. In parallel, as a control, we infected U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells at 104 cells/well with the same amounts of mutant pseudoviruses and the wild-type (WT) HXB2 pseudovirus. After 3 days of incubation, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed with 40 μl of the cell culture lysis reagent. The lysates were transferred to a white 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of the luciferase assay reagent. We measured the luciferase activity immediately and reported the infectivity of the pseudoviruses detected in the ACTOne-CXCR4 cells as the percentage of infection relative to the infectivity detected in the U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells.

SPR assays with BIAcore.

To measure the binding kinetics of NBD series compounds, we employed surface plasmon resonance (SPR; BIAcore 3000; GE Healthcare, Cleveland, OH). The final concentration of Yu2 core protein was fixed at 62.5 nM in an HBS buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% surfactant P20) containing 4% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The buffer and sCD4 or NBD series compounds were added to the core proteins and incubated at room temperature for 1 h before passing over the chip. sCD4 or NBD series compounds were used in a 15-fold or 50-fold excess to the core protein, respectively. The surface of the CM5 chip was immobilized with anti-human IgG, followed by the capture of IgG 17b to 300 response units (RU). Then, the core protein alone or the core protein in the presence of sCD4 or NBD series compounds was passed over the 17b-captured surface. The association time was 2 min; the dissociation time was 5 min. To regenerate the surface, we introduced 3 M MgCl2 via two pulse injections (25 s per injection) at 60 μl/min. We analyzed the data using BiaEvaluation software (BIAcore, Uppsala, Sweden).

Measurement of antiviral activity. (i) Single-cycle infection assay in TZM-bl cells.

We measured the inhibitory activities of NBD-09027, -11008, -11018, and -556 on HIV-1 pseudotyped viruses expressing HXB-2 Env or Env from the panel of standard reference subtypes A, A/D, A2/D, A/E, A/G, B, C, and D. We prepared the pseudoviruses by transfecting HEK 293T cells with a mixture of an Env-deleted backbone proviral plasmid, pSG3Δenv, and Env expression vector DNA. Briefly, 100 μl of TZM-bl cells at 1 × 105 cells/ml was added to the wells of a 96-well tissue culture plate and cultured at 37°C overnight. Fifty microliters of a test compound at graded concentrations was mixed with 50 μl of the HIV-1 pseudovirus at about 100 TCID50. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the mixture was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and lysed with 50 μl of the cell culture lysis reagent; 20 μl of lysate was transferred to a white 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of the luciferase assay reagent. We immediately measured the luciferase activity with a Tecan Infinite M1000 reader and then calculated the percent inhibition by the compounds and IC50s by using GraphPad Prism software.

(ii) Single-cycle infection assay in U87-CD4-CXCR4 and U87-CD4-CCR5 cells.

U87-CD4-CXCR4 and U87-CD4-CCR5 cells were plated in 96-well plates at 104 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37°C. We prepared the pseudoviruses NL4-3–ADA-Luc (R5 tropic) and NL4-3–HXB2-Luc (X4 tropic) by transfecting the HEK 293T cells with a mixture of pNL4-3.Luc.R.E DNA and Env expression vector pSVIIIenv-ADA or Env expression vector pHXB2-Env DNA. Briefly, the pseudoviruses were preincubated with escalating doses of NBD compounds for 30 min. The mixtures were then added to the respective cells and incubated for 3 days. Cells were washed 2 times with PBS and lysed with 40 μl of cell culture lysis reagent. Lysates were transferred to a white 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of the luciferase assay reagent. Immediately thereafter, we measured the luciferase activity, as described above, to calculate the IC50.

Cytotoxicity assay.

The cytotoxicity of test compounds in TZM-bl and U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells was measured by a colorimetric method using XTT [(sodium 3′-(1-(phenylamino)-carbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro) bezenesulfonic acid hydrate; PolySciences, Inc., Warrington, PA] as previously described (51). Briefly, 100-μl aliquots of a compound at graded concentrations were added to an equal volume of cells (105/ml) in wells of 96-well plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 days. Four hours after the addition of XTT, we quantitated colorimetrically the soluble intracellular formazan at 450 nm. We calculated the percent cytotoxicity and the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values as described above.

Isolation and characterization of resistant viruses.

To select HIV-1 resistant variants, Jurkat cells were infected with WT NL4-3 in the presence of 30 μM NBD-11008 or NBD-09027. Once a week, we monitored viral replication by measuring p24 amounts in the culture medium via a sandwich ELISA. After 20 passages (7 weeks of culture) we detected p24 in the cell culture medium of the cells treated with 30 μM NBD-11008, and after 27 passages (9 weeks of culture) we detected p24 in the culture medium of the cells treated with NBD-09027. Based on these findings, we decided to slowly escalate the concentration of compound of the culture resistant to 30 μM NBD-11008, up to 127 μM, and continuously refresh the cell culture by adding fresh cells during the process. In the case of NBD-09027, the concentration could not be escalated beyond 55 μM due to cellular toxicity. We collected cellular and viral samples at different passages. Viruses obtained from treated and untreated cultures were repassaged in fresh Jurkat cells. Twenty hours postinfection, the cells were washed with PBS to eliminate noninfectious viruses and then added to the culture with fresh medium. Six days later, the HIV-1-containing supernatants were filtered to remove cell debris and p24 was quantified by ELISA. We then determined titers of the viruses, normalized by p24 amounts, by infecting TZM-bl cells, and we calculated the TCID50 with the Spearman-Karber statistical method.

Genotyping of resistant and control viruses.

To identify the mutations conferring resistance to NBD-11008 and NBD-09027, we used a whole-blood DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) to extract genomic DNA from the following cells: (i) cells harboring the viruses resistant to 53 μM (passage 29), 74 μM (passage 33), and 127 μM (passage 43) NBD-11008; (ii) cells harboring the viruses resistant to 45 μM (passage 28) and 55 μM (passage 33) NBD-09027; (iii) cells harboring control WT virus. The entire Env coding region was amplified by PCR using the Expand High-Fidelity DNA polymerase kit (Roche) and then sequenced. We analyzed viral DNA sequences by using Geneious 6.1.4 software (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Drug sensitivity of mutant Env pseudovirus.

We introduced mutations into the pHXB2-Env expression vector via site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using mutagenic oligonucleotides, and we verified them by sequencing the entire Env gene of each construct. To measure the activities of the compounds against the pseudoviruses expressing different mutations, U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells were infected with the mutant Env pseudoviruses pretreated for 30 min with seven different concentrations of NBD compounds and incubated for 3 days. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed with 40 μl of cell culture lysis reagent. Lysates were transferred to a white 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent. We immediately measured the luciferase activity to calculate the IC50, as described above.

Crystallization, structure determination, and refinement.

As described previously, we purified the clade A/E93TH057 HIV-1 gp120 core (28) and concentrated the protein to ∼10 mg/ml in a buffer containing 2.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 350 mM NaCl, and 0.02% NaN3. For cocrystallization, NBD-09027 or NBD-10007 dissolved in 100% DMSO was added to the concentrated gp120 protein to maintain the final concentration of 100 μM in 5% (vol/vol) DMSO. Crystals were grown by mixing 0.5 μl of protein and 0.5 μl of reservoir solution containing 10 to 12% polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000), 5% isopropanol, and 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5) by vapor diffusion using the hanging drop technique. Crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution containing 30% ethylene glycol, 12% PEG 8000, 5% isopropanol, and 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5) and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data at 2.2 Å and 2.5 Å resolution were collected from a single crystal of NBD-10007-bound HIV-1 gp120 core and NBD-09027-bound HIV-1 gp120 core, respectively, on beamline 22-ID of SER-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (Lemont, IL). Data were integrated and scaled with HKL2000 (52).

Structures were solved by molecular replacement using the unliganded clade A/E93TH057 HIV-1 gp120 core structure (PDB ID 3TGT) as a search model with AutoMR in the PHENIX software suite (Berkeley, CA) (53). NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 were fitted into the Phe43 cavity manually by using COOT (54); the structures were refined using phenix.refine (53).

Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Figures were generated with PyMOL (PyMOL Molecular Graphics system, version 2.0; Schrödinger, LLC, Portland, OR) and LIGPLOT (55).

Data analyses.

We performed statistical analysis to compare the NBD compounds with the control, NBD-556. For adjustment of multiple comparisons, we implemented a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's test, with the significance level set at 0.05. We conducted all analyses using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

NBD compounds prevent cell-cell fusion.

We found that the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein mediates both viral entry and cell-cell fusion, leading us to expect that entry inhibitors also would inhibit the fusion process. As a first step in the identification of the target of the NBD compounds, we set up a cell-cell fusion inhibition assay between HIV-1IIIB-infected H9 cells and MT-2 cells, which predominantly express the CXCR4 coreceptor, as described previously (49). We used NBD-556 as the control based on earlier evidence that it inhibits cell-cell fusion (14). The results confirmed that these compounds inhibit cell-cell fusion between H9/HIV-1IIIB and MT-2 cells (IC50, ∼2.5 to 4.5 μM) and have the potential to be entry inhibitors (Table 1). NBD-09027 and NBD-11008 showed an almost-2-fold improvement in activity compared to NBD-556.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory activities of NBD compounds

| Compound | IC50a (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cell-cell fusion | CD4-gp120 interaction | |

| NBD-09027 | 2.3 ± 0.5b | 6.2 ± 0.8b |

| NBD-10007 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 10.7 ± 0.7 |

| NBD-11008 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 13.8 ± 0.8b |

| NBD-11009 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | ND |

| NBD-11018 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 1.3 |

| NBD-556 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 8.9 ± 1.4 |

Values are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. ND, not determined.

Significantly different from results for NBD-556 (P < 0.05).

NBD compounds block the gp120-CD4 interaction.

NBD-556 inhibited the interaction between cellular CD4 and HIV-1 gp120 (14), suggesting that the analogs derived from this molecule would also inhibit this interaction. To confirm this, we performed a capture ELISA with recombinant gp120 from HIV-1IIIB to measure the effect of NBD-09027 and its analogs on the gp120-CD4 interaction. In this assay, the compounds in graded concentrations were incubated in wells of polystyrene plates containing recombinant gp120, which was captured by coating the wells with sheep anti-gp120 antibody D7324. Based on the data, these compounds inhibited this interaction with an IC50 in the range of 6.7 to 15 μM, similar to the data obtained with NBD-556 (Table 1).

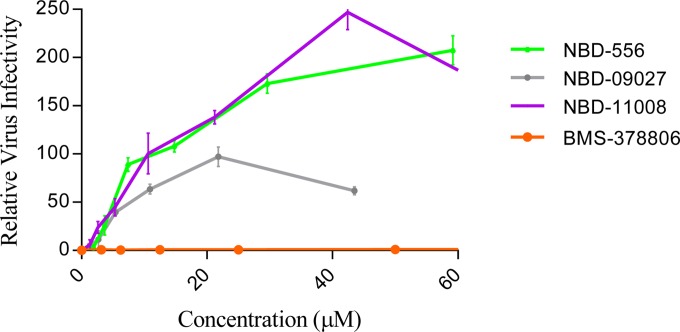

To confirm that the NBD compounds block the interaction between gp120 and CD4, we evaluated the effects of these compounds on the infection of a CD4-dependent virus (ADA) in Cf2Th/CD4-CCR5 target cells that express CD4 and CCR5 and on the infection of a CD4-independent mutant virus (ADA-N197S) in Cf2Th-CCR5 target cells that express the CCR5 coreceptor but not CD4. We detected that the NBD compounds inhibited the CD4-dependent virus in a dose-dependent manner (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), as observed previously by our group (14) and others (24) for NBD-556 and NBD-557. However, none of the compounds tested inhibited the infection of the target cells by the CD4-independent virus ADA-N197S (see Fig. S1). The results suggested that NBD compounds inhibit HIV-1 entry and infection primarily by blocking the gp120-CD4 interaction. It has been shown that NBD-556 can also act as a CD4 agonist by promoting CCR5 binding and enhancing HIV-1 entry into CD4-negative cells expressing CCR5 (25). To further evaluate the activity of the NBD compounds, we infected CD4-negative Cf2Th-CCR5 cells with the recombinant CD4-dependent ADA virus in the presence of various concentrations of NBD-09027 and NBD-11008. We used NBD-556 and BMS-378806 as controls. Our data confirmed those of others (25), specifically, that NBD-556 enhanced HIV-1 entry into CD4-negative cells whereas BMS-378806 did not (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that NBD-11008 produced an enhancement of infectivity similar to that of NBD-556. At the same time, the enhancement by NBD-09027 was about 2-fold lower than that by NBD-556, indicating that not all NBD series compounds are equally able to enhance HIV-1 infection in CD4-negative cells.

FIG 2.

Infectivity of CD4-negative CCR5-positive cells by CD4-dependent virus. CD4-negative Cf2Th-CCR5 cells were infected with recombinant HIV-1 CD4-dependent NL4-3–ADA-Luc in the presence of increasing concentrations of NBD-556, NBD-09027, NBD-11008, and BMS-378806. Ther relative virus infectivity specifies the amount of infection detected in the presence of a compound relative to the infection detected in the absence of that compound. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, and the values represent the means ± standard deviations.

Inhibitory activity of NBD compounds is independent of binding to CXCR4 or CCR5 coreceptors.

We tested the effect of the most active NBD molecules on virus-cell fusion in an assay with both R5- and X4-tropic pseudoviruses. To this end, U87-CD4-CCR5 and U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells were infected with pseudovirus NL4-3–ADA-Luc (R5 tropic) and NL4-3–HXB2-Luc (X4 tropic), respectively, and treated with escalating doses of NBD compounds. Our results suggested that these compounds inhibit virus-cell fusion in both assays, although they exhibited better activity against X4-tropic viruses. Specifically, the IC50 for the R5-tropic virus was in the range of 1.7 to 17.3 μM; for the X4-tropic virus it was in the range of 1.6 to 8.6 μM (Table 2). NBD-11018 had the best activity against both viruses.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory activities of NBD compounds on CCR5-tropic and CXCR4-tropic HIV-1

| Compound | IC50a (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| U87-CD4-CCR5 cells, NL4-3–ADA-Luc virus | U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells, NL4-3–HXB2-Luc virus | |

| NBD-09027 | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 0.7 |

| NBD-10007 | 6.3 ± 0.4c | 6.8 ± 0.7 |

| NBD-11008 | 17.3 ± 0.4c | 4.8 ± 0.3b |

| NBD-11009 | 16 ± 0.6c | 3.8 ± 0.6c |

| NBD-11018 | 3.7 ± 0.4c | 4.5 ± 0.6b |

| NBD-556 | 11 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 0.8 |

Values are means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments.

Significantly different from results for NBD-556 (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from results for NBD-556 (P < 0.0001).

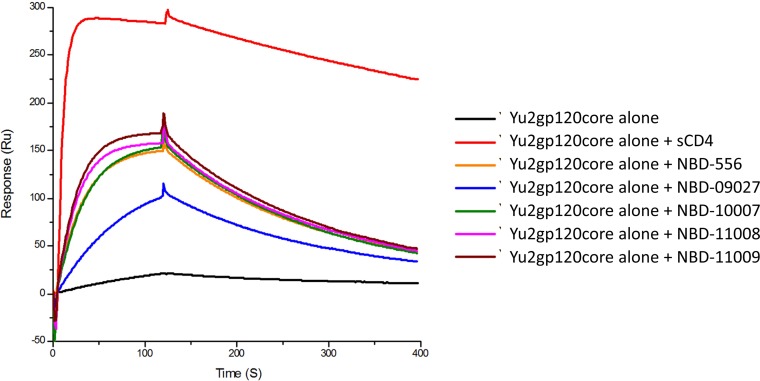

NBD series compounds induce the coreceptor binding site on the YU2 core gp120.

Based on SPR studies and using sCD4 as a reference molecule, we probed whether NBD series compounds induce a similar conformation in gp120 as CD4 does, termed the CD4-induced (CD4i) conformation, which can be recognized by MAb 17b. As expected, in the presence of a 15-fold excess of sCD4, the YU2 core gp120 demonstrated enhanced binding to MAb 17b compared to the YU2 core gp120 alone. Treatment of the core with NBD series compounds also showed enhanced binding to MAb 17b, although it required the presence of a 50-fold excess of these small molecules (Fig. 3). Notably, NBD-09027 had a greatly reduced ability to activate the CD4-induced conformation, indicating that this compound has a lower tendency to act as an agonist. The results with this compound and CD4-negative cells revealed that NBD-09027 is about 2-fold less efficient in enhancing infection in CD4-negative cells. Taken together, the findings of the biophysical study and the cell-based assay suggest that NBD-09027 has a lower tendency to act as an agonist (Fig. 2).

FIG 3.

Impact of NBD series compounds on the binding between MAb 17b and YU2 core gp120 protein. The YU2 core gp120 was passed over the anti-human IgG-captured 17b in the absence or presence of saturated NBD series compounds or sCD4 (control). The injection time was 2 min and the disassociation time was 5 min. The graph is representative of results from two independent experiments.

NBD compounds exhibit antiviral activity against diverse HIV-1 clades of Env-pseudotyped reference viruses.

Despite the fact that the amino acid sequence lining the Phe43 cavity is highly conserved, the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are, in general, highly variable. Therefore, we decided to test the breadth of inhibitory activity of NBD-09027 and its analogs against a large panel of 53 HIV-1 Env-pseudotyped reference viruses of different clades in a single-cycle infection assay. These pseudoviruses exhibited a neutralization phenotype that is typical of most primary HIV-1 isolates (39, 43, 56). We compared their activities with that of the earlier compound, NBD-556, and analyzed the data with a one-way ANOVA, implementing Dunnett's test for adjustments of multiple comparisons and with a significance level set at 0.05. Four representative dose-dependent inhibition plots of the neutralization assay of selected pseudoviruses (NIH 11313, 11906, 11601, and 11890) are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. As evident in Table 3, NBD-556 was active against all the viral subtypes tested, including pseudoviruses from clade C, exhibiting an IC50 in the range of 1.5 to 21 μM. NBD-11008 was the least consistent compound tested, displaying better activity against the pseudoviruses from clade B and poor activity against the pseudoviruses from clades A, A/D, A2/D, A/E, A/G, C, and D. NBD-09027 and NBD-11018 compounds were consistently active against all the viral subtypes tested; the only exceptions were that NBD-09027 demonstrated poor activity against 4 pseudoviruses from clade C while NBD-11018 exhibited a 3-fold improvement with respect to the original compound, NBD-556, with an IC50 in the range of 0.6 to 7.7 μM. Of note, the NBD compounds were also equally active against two subtype B dual-tropic (R5X4) HIV-1 isolates (NIH 11563 and 11578). The toxicity data (CC50 values in Table 3) verified that the NBD compounds have a good selectivity index (SI, calculated as the CC50/IC50 ratio). Moreover, none of these compounds showed activity against control viruses A-MLV and VSV, suggesting that the inhibitory activity of these NBD series compounds is specific to HIV-1.

TABLE 3.

Neutralization activities of NBD compounds against a large panel of HIV-1 Env pseudoviruses

| HIV subtype or control virus | NIH no. | Env | IC50 (μM) ± SDa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD-556 | NBD-09027 | NBD-11008 | NBD-11018 | |||

| A | 11887 | Q259env.w6 | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 2 ± 0.2d | 4.8 ± 0.6c | 5.4 ± 0.2c |

| 11888 | QB726.70 M.ENV.C4 | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3d | 13.4 ± 1.2c | 1.9 ± 0.1d | |

| 11890 | QF495.23 M.ENV.A1 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1c | 5.4 ± 0.6c | 6.6 ± 0.5c | |

| 11889 | QB726.70 M.ENV.B3 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 3 ± 0.6c | >16d | 4.5 ± 0.4c | |

| 11891 | QF495.23 M.ENV.A3 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 3 ± 0.2c | 10.7 ± 1.2c | 4.1 ± 0.5c | |

| 11892 | QF495.23 M.ENV.B2 | 8.9 ± 0.9 | 3 ± 0.4d | 11.3 ± 0.8c | 4 ± 0.4d | |

| BG505.T332N | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 19.1 ± 4.5c | 7.4 ± 0.7 | ||

| KNH1144 | 9.7 ± 2 | 4.9 ± 0.4c | 32.5 ± 3d | 8.4 ± 0.7 | ||

| A/D | 11901 | QA790.204I.ENV.A4 | 12.3 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 0.4d | >21d | 5.4 ± 1.3c |

| 11903 | QA790.204I.ENV.C8 | 5 ± 1 | 3 ± 0.3c | >21d | 6.4 ± 0.3c | |

| 11904 | QA790.204I.ENV.E2 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.1d | >21d | 4.1 ± 0.2d | |

| A2/D | 11905 | QG393.60 M.ENV.A1 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2d | >21d | 5.6 ± 0.2c |

| 11906 | QG393.60 M.ENV.B7 | 20.8 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 0.3d | >21 | 3.7 ± 0.3d | |

| 11907 | QG393.60 M.ENV.B8 | 11.1 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 0.1c | >42d | 4.3 ± 0.6d | |

| A/E (potential) | 11603 | CRF01_AE clone 269 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.2c | 8 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 0.4c |

| A/G | 11601 | CRF02_AG clone 263 | 8.8 ± 1.1 | 3 ± 0.6d | 14 ± 0.4d | 4.3 ± 0.3c |

| 11602 | CRF02_AG clone 266 | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2c | >21d | 3.6 ± 0.3c | |

| 11605 | CRF02_AG clone 278 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 2 ± 0.4 | 16 ± 0.7d | 5.1 ± 0.95c | |

| B | B41 | 8.3 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 0.5c | 11.6 ± 2 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | |

| 11563 | p1058_11.B11.1550b | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2c | 1.9 ± 0.2c | 1.2 ± 0.2d | |

| 11578 | pWEAUd15.410.5017b | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.2c | 1.9 ± 1c | 5 ± 0.4 | |

| 11017 | 6535, clone 3 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.3c | 11.7 ± 1.4c | 5.9 ± 0.2 | |

| 11018 | QH0692, clone 42 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 2 ± 0.3c | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.2c | |

| 11022 | PVO, clone 4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 2.2c | 7.7 ± 1.3c | |

| 11023 | TRO, clone 11 | 5 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.5c | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.4c | |

| 11024 | AC10.0, clone 29 | 8.9 ± 3 | 1.4 ± 0.3c | 16.3 ± 0.6c | 2.2 ± 0.3c | |

| 11033 | pWITO4160 clone 33 | 6 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.7c | 6 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 1 | |

| 11035 | pREJO4541 clone 67 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 0.2c | 9.8 ± 0.6c | 2.6 ± 0.3c | |

| 11036 | pRHPA4259 clone 7 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.3c | 1.7 ± 0.6c | 4.7 ± 0.3c | |

| 11037 | pTHRO4156 clone 18 | 4 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | |

| 11038 | pCAAN5342 clone A2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.1c | 0.8 ± 0.3c | |

| 11058 | SC422661.8 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.2d | 2.5 ± 0.3d | 1.3 ± 0.1d | |

| C | 11306 | Du156, clone 12 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.13 | 9.2 ± 1.2c | 1.7 ± 0.2c |

| 11307 | Du172, clone 17 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 3 ± 0.38 | 31 ± 1.2d | 5.3 ± 0.2 | |

| 11308 | Du422, clone 1 | 11.8 ± 2.9 | 15.9 ± 0.4c | >42d | 2.5 ± 0.1c | |

| 11309 | ZM197 M.PB7 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | >21d | >42d | 2.3 ± 0.2d | |

| 11310 | ZM214 M.PL15 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | >21d | >42d | 2.9 ± 0.4c | |

| 11311 | ZM233 M.PB6 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 1.3 | 11.3 ± 0.9c | 2.5 ± 0.5c | |

| 11312 | ZM249 M.PL1 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 0.6c | >42d | 2.5 ± 0.2c | |

| 11313 | ZM53 M.PB12 | 13.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2d | >42d | 4.3 ± 0.6d | |

| 11314 | ZM109F.PB4 | 10.4 ± 3.5 | 1.2 ± 0.2c | >42d | 3 ± 0.1c | |

| 11315 | ZM135 M.PL10a | 1.5 ± 0.01 | 0.7 ± 0.13 | 12.4 ± 2.7d | 0.61 ± 0.1 | |

| 11316 | CAP45.2.00.G3 | 7.9 ± 0.87 | 4.7 ± 0.95c | 17.5 ± 0.5d | 3.4 ± 0.4c | |

| 11317 | CAP210.2.00.E8 | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 15.1 ± 1.5 | >42d | 3.2 ± 0.6d | |

| 11908 | QB099.391 M.ENV.B1 | 5.1 ± 1.8 | 2.1 ± 0.7c | >21d | 6.5 ± 0.8 | |

| 11909 | QB099.391 M.ENV.C8 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2d | >10.6d | 4.6 ± 0.5c | |

| D | 11911 | QA013.70I.ENV.H1 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.6c | 11.8 ± 0.9d | 5.5 ± 0.7c |

| 11912 | QA013.70I.ENV.M12 | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1c | >42d | 2.4 ± 0.2c | |

| 11913 | QA465.59 M.ENV.A1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2d | 2.5 ± 0.2d | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 11914 | QA465.59 M.ENV.D1 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.7c | 8.3 ± 0.5c | 3.5 ± 0.5 | |

| 11916 | QD435.100 M.ENV.B5 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 0.3c | >32d | 3.9 ± 0.4 | |

| 11917 | QD435.100 M.ENV.A4 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 0.3c | |

| 11918 | QD435.100 M.ENV.E1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 0.2d | 3.4 ± 0.4d | |

| Control viruses | ||||||

| A-MLV | >60 | >32 | >45 | >30 | ||

| VSV | >60 | >32 | >45 | >30 | ||

The reported IC50s are means ± standard deviations (n = 3). The NBD CC50s were >60, >32, >85, and >60 for NBD-556, NBD-09027, NBD-11008, and NBD-11018, respectively.

R5X4-tropic viruses; all the rest were R5-tropic viruses.

Significantly different from results for NBD-556 (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from results for NBD-556 (P < 0.0001).

Selection of resistant viruses.

To confirm the binding mode of NBD compounds, HIV-1 NL4-3 was passaged in Jurkat cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of NBD-11008 (chosen for its lower toxicity and IC50) and NBD-09027. While increasing the dose of NBD-11008, we collected cellular and viral samples at 53 μM, 74 μM, and 127 μM NBD-11008. The dose of NBD-09027 in culture could be escalated only up to 55 μM due to cellular toxicity; we therefore collected cellular and viral samples at 44 μM and 55 μM NBD-09027. The NL4-3 HIV-1 virus obtained from NBD-11008- and NBD-09027-treated cultures and the virus obtained from untreated cultures were repassaged in fresh Jurkat cells.

We titered P24-normalized viruses on TZM-bl cells to measure the level of replication-competent infectious virus. We found that the viruses released in the supernatant of early passages of NBD-11008 cultures (53 μM and 74 μM) had low infectivity (less than 10%) with respect to the WT virus. In contrast, the virus released at late passages (127 μM NBD-11008) had higher (90%) infectivity with respect to the WT virus (data not shown). The viruses resistant to 44 μM and 55 μM NBD-09027 were as infectious as the WT virus (data not shown).

Identification and characterization of NBD-resistant mutants.

To identify the changes responsible for NBD resistance, we extracted genomic DNA from cellular samples, and amplified and sequenced the full HIV-1 Env gene. Initially, we identified 4 amino acid substitutions in the sample resistant to 53 μM NBD-11008 (Table 4): V208I located in the gp120 V2 loop, S405L located in the V4 loop, and two adjacent substitutions, NN301–302KI, located in the N-linked glycosylation site (NNT becomes KIT) of the V3 loop. We detected the same amino acid substitutions in the sample resistant to 74 μM NBD-11008. Additionally, a new substitution, S375N, appeared with low frequency (2/5 samples) in the CD4 binding site. When we analyzed the profile of the sample resistant to the higher dose of NBD-11008 (127 μM), we identified the same substitutions detected at the lower concentration; furthermore, three additional amino acid substitutions (S142N, K432Q, and E560D) emerged with lower frequencies. However, the substitution at the CD4 binding site, S375N, detected at the lower dose (74 μM), was replaced with S375Y and was found in all samples (14/14). A similar phenomenon was previously observed in the b12 MAb resistance study, where the substitutions Q389P and Q389L were completely replaced by Q389K, resulting in increased resistance to neutralization (57). In both samples collected from cultures of NBD-09027 at 44 μM and 55 μM, we identified amino acid changes in only three sites: the two adjacent substitutions NN301–302KI, a substitution in the CD4 binding region, K432R, and one in gp41, V782L.

TABLE 4.

Amino acid substitutions detected by sequencing NL4-3 HIV-1 resistant to different doses of NBD-11008 and NBD-09027

| Substitutiona | Frequency of detection after treatment with: |

Location | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD-11008 |

NBD-09027 |

|||||

| 53 μM | 74 μM | 127 μM | 44 μM | 55 μM | ||

| S142N | 7/14 | V1 | ||||

| V208I | 3/3 | 2/5 | 9/14 | V2 | ||

| NN301–302KI | 3/3 | 5/5 | 14/14 | 3/3 | 3/3 | V3 |

| S375Y | 2/5 (S375N) | 14/14 | CD4 binding site | |||

| S405L | 3/3 | 5/5 | 14/14 | V4 | ||

| K432Q | 3/14 | 3/3 (K432R) | 3/3 (K432R) | CD4 binding site | ||

| E560D | 3/14 | gp41 | ||||

| V782L | 3/3 | 3/3 | gp41 | |||

Numbering is based on the HIV HXB2 sequence in the Los Alamos HIV database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/).

Impact of amino acid substitutions on HIV-1 entry and resistance to NBD compounds.

As a next step, we wanted to confirm that the amino acid substitutions were responsible for the resistance of the NL4-3 HIV-1 to the NBD compounds. We introduced selected NBD-11008-induced mutations (V208I, NN301–302KI, S375Y, and S405L) and NBD-09027-induced mutations (NN301–302KI, K432R, and V782L) into the pHXB2-Env expression vector by site-directed mutagenesis. We constructed pHXB2-Env expression vector derivatives containing combinations of the 4 and 3 substitutions, respectively. To prepare the HIV-1 pseudoviruses capable of single-cycle infection, 293T cells were transfected with a mixture of WT or mutated pHXB2-Env-expressing single, double, triple, and quadruple mutations and the Env-deleted proviral backbone plasmid pNL4-3.Luc.R.E. Pseudovirus titers were determined for U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells.

We observed that pseudoviruses expressing the single mutations NN301–302KI, S375Y, and S405L, which were detected in the selection experiments with NBD-11008, or a combination of these mutations were as infectious as the WT, while the pseudovirus expressing the V208I mutation had very low infectivity (10 to 20% with respect to the WT). Moreover, the combination of V208I with the other mutations to obtain double mutants (V208I/NN301–302KI, V208I/S375Y, and V208I/S405L) or triple mutants (V208I/NN301–302KI/L405S, V208I/NN301–302KI/S375Y, and V208I/S375Y/L405S) resulted in a loss of viral viability, as indicated by low or no infectivity (1 to 10% with respect to the WT) (data not shown). V208I mutation had less impact on infectivity when combined with NN301–302KI, S375Y, and S405L in the quadruple mutant pseudovirus. These findings suggest that all the mutations may be required for HIV-1 to acquire complete resistance to NBD-11008 and to rescue the replication capacity of the virus.

On the contrary, we observed no differences in infectivity with the mutant pseudoviruses, detected in the selection experiments using NBD-09027, that carried a single mutation (NN301–302KI, K432R, and V782L) or a combination of these mutations (NN301–302KI/K432R, NN301–302KI/V782L, K432R/V782L, and NN301–302KI/K432R/V782L).

To verify whether the amino acid substitutions we detected were responsible for the emergence of resistance to the NBD compounds, U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells were infected with WT and mutant HIV-1 pseudoviruses in the absence or presence of NBD-556, NBD-09027, NBD-11008, and BMS-378806, used as a control. Luciferase activity was measured to calculate the IC50s. We noted that S405L was not a significant substitution, as indicated by its IC50, which was similar to that obtained for the HIV-1 HXB2 WT (Table 5). We also observed that V208I and NN301–302KI, when expressed as single mutations, conferred about 4- and 6-fold resistance to NBD-556, respectively, and about a 10-fold resistance to NBD-09027, while higher resistance to NBD-11008 (about 13- and 21-fold, respectively) was conferred. These mutants were sensitive to BMS-378806. The S375Y substitution conferred the highest resistance, not only to NBD-556 (8-fold), NBD-09027 (15-fold), and NBD-11008 (20-fold) but also to the highly potent entry inhibitor BMS-378806 when expressed as single mutation or in combination with the other mutations. This finding was supported by a recent study establishing that mutating S375 with any bulky amino acid, such as W, M, or H, renders the mutant pseudoviruses resistant to NBD series compounds (20). Furthermore, another recent study suggested that the S375H substitution might be responsible for the resistance of the CRF01_AE HIV-1 to the entry inhibitor BMS-599793 (58). In our own investigations into the effect of the NBD compounds on the pseudovirus carrying the S375H substitution, we observed that the mutant was resistant to all NBD compounds (>2-fold), with NBD-11008 exhibiting the highest level of resistance (∼14-fold). We also found that V782L mutants obtained with NBD-09027 conferred resistance only to NBD-09027 (4.3-fold), whereas the K432R substitution in the CD4 binding region yielded about 5-fold resistance to NBD-09027 and NBD-11008. We also constructed a set of mutant pseudoviruses based on a BMS-378806 resistance study reported earlier (12). We selected three single substitutions—M475I, M426L, and M434I—and the combination of mutations, M434I–I595F, which conferred the highest resistance to BMS-378806 by HIV-1 LAI. As expected, the results suggested that those three mutations induce resistance to 400 nM BMS-378806, but only the M475I and M426L mutations conferred resistance to NBD-09027 and -11008.

TABLE 5.

Sensitivities of mutant pseudoviruses to NBD compoundsa

| Virus | IC50 (μM) ± SDa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBD-556 | NBD-09027 | NBD-11008 | BMS-378806 (nM) | |

| HXB2 WT | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 3 ± 1 | ∼1 |

| NBD-11008 mutants | ||||

| V208I | ∼30 | ∼43 | ∼42 | ∼1 |

| NN301–302KI | >48 | >43 | ∼64 | ∼1 |

| S375Y | ∼60 | ∼65 | >64 | >400 |

| S405L | 7.9 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | ∼1 |

| NN301–302KI/S375Y | ≥60 | ∼65 | >64 | >400 |

| NN301–302KI/S405L | >60 | >65 | >64 | ∼1 |

| S375Y/S405L | >45 | >43 | ∼64 | >400 |

| NN301–302KI/S375Y/S405L | >60 | >65 | >64 | >400 |

| V208I/NN301–302KI/S375Y/S405L | ∼45 | ∼43 | >42 | >400 |

| NBD-09027 mutants | ||||

| NN301–302KI | >48 | >43 | ∼64 | ∼1 |

| K432R | 14.8 ± 3.3 | 21.7 ± 1.2 | 16.4 ± 1.5 | ∼1 |

| V782L | 9.2 ± 1 | 19.1 ± 2.7 | 7.8 ± 3 | ∼1 |

| NN301–302KI/K432R | 38 ± 0.6 | ∼30 | ∼42 | ∼1 |

| NN301–302KI/V782L | 13.8 ± 1.1 | 19.1 ± 3 | 15.5 ± 1.3 | ∼1 |

| K432R/V782L | ∼21 | ∼40 | ∼38 | ∼1 |

| NN301–302KI/K432R/V782L | >37 | >65 | ∼32 | ∼1 |

| BMS-378806 mutants | ||||

| M475I | ∼45 | ∼33 | ∼32 | >400 |

| M426L | 14.4 ± 0.3 | 11.9 ± 1.6 | >38 | >400 |

| M434I | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.68 ± 0.1 | >400 |

| M434I-I595F | 4.7 ± 1 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | >400 |

| S375H | 19 ± 1.5 | 9 ± 0.7 | >43 | >400 |

Values representing the means ± standard deviations were obtained from three independent experiments. The NBD CC50s were >118, >87, >85 for NBD-556, NBD-09027, and NBD-11008, respectively.

NBD-resistant viruses do not infect CD4-negative cells.

To verify whether the viruses obtained from the selection with NBD-09027 and NBD-11008 acquired a CD4-independent phenotype that does not require interaction with CD4 for infection, we infected, in parallel, CD4-negative ACTOne-CXR4 cells and CD4-positive U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells with the same amounts of mutant pseudovirus or with WT HXB2 as a control. We infected both cell lines with mutant viruses carrying a single amino acid substitution (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). None of these mutants acquired the ability to efficiently infect the CD4-negative ACTOne-CXR4 cells.

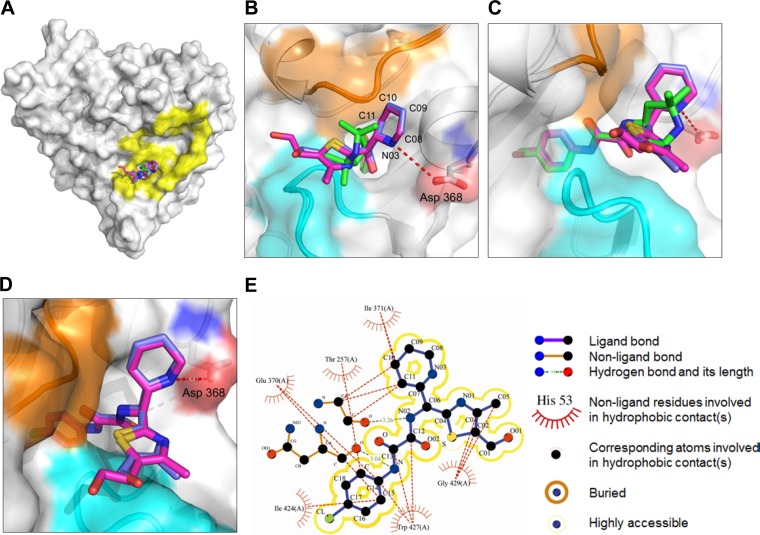

Crystal structures of NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 in complex with the HIV-1 gp120 core.

To understand the structural basis of enhanced affinity and potency, we determined crystal structures of NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 in complex with HIV-1 clade A/E93TH057 gp120 core at 2.5 Å and 2.2 Å resolution, respectively. We used clade A/E gp120 for crystallization to take advantage of its intrinsic nature to form well-diffracting crystals, as observed in our work published previously (20). However, due to the presence of histidine (His) at residue 375, which is part of the Phe43 cavity, NBD analogs do not bind to clade A/E gp120. Hence, we mutated H375 to Ser and were able to cocrystallize NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 in complex with clade A/E H375S mutant gp120. We solved the structures with molecular replacement, which revealed that, as expected, NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 bound to the Phe43 cavity of gp120 in the same manner as NBD-556 and NBD-557 (Fig. 4A to D). The chlorophenyl rings and oxalamide linkers were superimposable on those of NBD-556 and NBD-557 when the gp120s to which these NBD analogs bound were superimposed (Fig. 4C). That said, the replacements of the tetramethyl piperidine ring moiety were notably different from that found with NBD-557. The two rings reside outside the Phe43 cavity and bifurcate orthogonal to the oxalamide linker. The 6-membered rings of NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 reach out toward D368 and the 5-membered rings in the opposite direction (Fig. 4B to D). Carbon 10 in the 6-membered ring of NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 is within van der Waals distance with I371 on gp120 (Fig. 4B to E). The 5-membered ring nestles in the groove formed by the outer domain to the inner domain exit loop (orange in Fig. 4B to D) and the tip area of β20–21 (cyan in Fig. 4B to D), which enables carbons 01, 02, 03, and 05 of the 5-membered ring to make hydrophobic interactions with Gly429 on gp120 (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, nitrogen 03 in the 6-membered ring of NBD-10007 is located in close proximity (4.4 Å) to D368 (Fig. 4B). A further modification and optimization of the 6-membered ring is necessary to form a hydrogen bond with D368.

FIG 4.

Crystal structures of HIV-1 gp120 in complexes with NBD-09027 and NBD-10007. (A) Superposition of NBD-557 (green), NBD-09027 (light blue), and NBD-10007 (purple) in the Phe43 cavity of gp120 (surface representation). CD4 binding footprints are shown in yellow. (B) Close-up view of the Phe43 cavity in panel A. The three major areas to which the small molecules are in close proximity are highlighted in cyan, orange, and red for the tip of β20–21 (gp120 residues 426 to 429), the outer domain to the inner domain exit loop (gp120 residues 472 to 474), and Asp 368 on gp120, respectively. (C) Close-up view of the Phe43 cavity with NBD-557, NBD-09027, and NBD-10007 superimposed. (D) Close-up view of NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 superimposed. The tetramethyl piperidine ring of NBD-557 and its equivalent for NBD-09027 and NBD-10007 resides outside the Phe43 cavity. (E) Schematic diagram of interactions between NBD-09027 and residues on gp120.

We expect that the knowledge acquired from the analyses of the X-ray crystallographic structures of these inhibitors bound to gp120 will help in the design of potent antiviral agents targeted to HIV-1 gp120.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of NBD-556, the first NBD series CD4 mimetic, by our group in 2005 presented the opportunity to design newer antiviral compounds as therapeutics and microbicides (14). Since then, several research groups have expressed intense interest in understanding how such a small molecule of about 337 Da can exert such a remarkable effect—similar to that of a large protein, sCD4 (25). Three recent studies reported the X-ray structure of NBD-556 and its analogs in complex with the HIV1 gp120 core (20, 22, 28). These structures confirmed that these molecules all bind to the Phe43 cavity where CD4 binds. The structure of NBD-556 discloses a crucial piece of information: that it lacks the critical interaction with D368 of gp120, which is a major interaction residue for the binding of R59 of CD4. In response, we modified the tetramethyl piperidine ring of NBD-556 by introducing a butterfly-type scaffold containing a 2-piperidine ring and a thiazole ring (Fig. 1). Consequently, these compounds demonstrated improved antiviral activity in a single-cycle assay (29). We subsequently extended the antiviral assay with a large set of reference viruses representing diverse clades of HIV-1 clinical isolates. The antiviral activity of one of the compounds, NBD-09027, was improved considerably compared to NBD-556, reaching an IC50 as low as 700 nM against one of the HIV-1 clade C Env pseudoviruses. Most importantly, the new scaffold introduced in region III (Fig. 1) makes it possible to expand the structure-activity analysis so that these leads are more active and less toxic, thus overcoming a handicap of the tetramethyl piperidine scaffold in NBD-556. We have confirmed that these compounds inhibit cell-cell fusion, as well as the interaction between CD4 and gp120. Most significantly, the antiviral activity of these molecules does not depend on the coreceptor usage; in other words, these molecules work against R5-, X4-, and R5X4-tropic viruses.

Another point is that although NBD-556 inhibits HIV-1 entry, it can induce conformation changes in gp120 that may facilitate binding of the coreceptor (25, 27), enhancing infection in CD4-negative/CCR5-positive cells. These apparently opposing activities can be explained by the fact that in CD4+ CCR5+ cells, NBD-556 binds first to the CD4 binding site in gp120, thereby preventing binding with the CD4, a critical step in virus entry. Conversely, in CD4– CCR5+ cells, NBD-556 can, due to its CD4-mimicking characteristics, act similar to CD4 and bind to gp120 to activate a conformation suitable for binding to the coreceptor, thereby facilitating infection. We wanted to verify that the NBD compounds behave similar to NBD-556 regardless of the fact that the clinical relevance of CD4-independent HIV entry is largely unknown and that CD4-independent HIV-1 isolates have rarely been isolated from patients (59). Interestingly, the enhancement of infection by NBD-11008 was similar to that by NBD-556, but the enhancement of infection by NBD-09027 was about 2-fold lower. We obtained a similar result with NBD-09027 by using the SPR technique to measure its ability to induce the coreceptor binding site on gp120. We can conclude from the data that NBD-09027 exhibited partial agonist properties compared to other NBD compounds we tested, indicating that the structure of this molecule can be manipulated to reduce the agonist property and convert it to an antagonist to prevent any enhancement of infection in CD4-negative cells.

To ascertain that these NBD compounds with modified region III bind to the Phe43 cavity, we utilized both drug-induced resistance studies with NBD-09027 and NBD-11008 and X-ray structural studies with NBD-09027 and its analog, NBD-10007. The resistance study enumerated five major mutations at the highest dose of NBD-11008. However, in the case of NBD-09027, we identified only three major mutations: one of each located at the V3 loop, at the CD4 binding site, and in gp41. The majority of the mutations were located adjacent to the CD4 binding site on gp120. It was no surprise that mutations have been noted in the variable loop regions, which are in close proximity to the CD4 binding site (60), and have been shown to be affected by CD4 binding (61, 62). When we tested the sensitivity of the mutant pseudoviruses to the NBD compounds, the major impact we observed was on the mutants obtained from NBD-11008 passage. It appeared that the S375Y mutation demonstrated major resistance to all NBD compounds tested, either alone or in combination with other mutations. The S375H mutation common to most subtype CRF01_AE HIV–1 viruses, which showed resistance to BMS-378806 in this study, was reported earlier to confer resistance to a candidate microbicide drug, BMS-599793, targeted to gp120 (58). The S375Y mutant and any of its combinations proved remarkably resistant to BMS-378806 (63). Notably, in the case of resistant mutants obtained from the NBD-09027 passage, the major impact we observed was on the double mutant NN301–302KI, located in the V3 loop, and on V782, located in the gp41. In the absence of any structure of full envelope glycoprotein (gp160), it is difficult to ascertain the position of this mutant in gp41 relative to the CD4 binding site. Remarkably, none of these mutations had any effect on BMS-378806. It is worth mentioning that when we tested two mutants, M475I and M426L, as reported earlier (12), the M475I mutant exhibited resistance to all compounds tested, whereas the M426L mutant exhibited only marginal resistance to NBD-556 and NBD-09027 and complete resistance to NBD-11008 and BMS-378806. The frequency of the M475I mutation is reported to be high, whereas the frequency of M426L is low (12), which may provide a rationale for the differences in resistance noted against the viruses with these two mutations.

To establish a relationship between the poor sensitivity of NBD-09027 against the four pseudoviruses from clade C (Table 3) and the mutations identified in the resistance study (Table 4), we compared the Env sequences of the pseudoviruses from this clade. All the clones used in the assay carried the mutation K432R, with the exception of the clone NIH 11307, which carries K432Q; none of the clones carried the mutations NN301–302KI and V782L. Moreover, we were unable to discern a specific mutation or an amino acid sequence pattern that was common only to the four pseudoviruses that demonstrated poor sensitivity to NBD-09027.

Our next step was to determine the X-ray structure of the two selected NBD compounds, NBD-09027 and NBD-10007, with gp120 core, in order to confirm the binding mode of the NBD series compounds as well as to understand the interactions of the new scaffolds introduced at region III. The resulting data confirmed that despite the introduction of the new scaffold in region III, the newer NBD compounds bound to the Phe43 cavity in a manner similar to NBD-556. However, the new scaffold extends further and makes some additional contacts with other residues at the periphery of the cavity. The basic nitrogen of the piperidine ring, though now in close proximity to D368, does not form any H-bond or salt bridge with this residue, meaning that an additional design strategy is needed to establish this critical contact. The interaction of the D368 residue with the R59 of CD4 is critical for its high-affinity binding. It has also been reported recently that other NBD-556-type small-molecule mimetics became antagonists after this critical interaction was introduced (64, 65).

The emergence of resistant mutants within 3 to 4 months (43 passages) of treatment of the virus with the NBD series compounds clearly indicates that further improvements in both antiviral efficacy and resistance profiles are needed. We believe that the systematic study of the new series of NBD compounds on the breadth of antiviral activity, atomic-level structures, and HIV-1 resistance will facilitate optimization of this important class of inhibitors against HIV-1 as potential therapeutics and microbicides.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by funds from NIH grant R01 AI104416 (A.K.D.), the New York Blood Center (A.K.D.), and the Intramural AIDS—Targeted Antiretroviral Program (IATAP) of the NIH.

Use of Sector 22 (Southeast Region Collaborative Access Team) at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science contract W-31-109-Eng-38.

We thank Vijay Nandi of the New York Blood Center for her assistance in statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 July 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03339-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooley LA, Lewin SR. 2003. HIV-1 cell entry and advances in viral entry inhibitor therapy. J. Clin. Virol. 26:121–132. 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang S, Debnath AK. 2000. Development of HIV entry inhibitors targeted to the coiled coil regions of gp41. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269:641–646. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh IP, Chauthe SK. 2011. Small molecule HIV entry inhibitors. Part II. Attachment and fusion inhibitors: 2004–2010. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 21:399–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffalo ML, James CW. 2003. Enfuvirtide: a novel agent for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Ann. Pharmacother. 37:1448–1456. 10.1345/aph.1D143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman-Blum SS, Fung HB, Bandres JC. 2008. Maraviroc: a CCR5-receptor antagonist for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Clin. Ther. 30:1228–1250. 10.1016/S0149-2918(08)80048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacArthur RD, Novak RM. 2008. Maraviroc: the first of a new class of antiretroviral agents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:236–241. 10.1086/589289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393:648–659. 10.1038/31405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DH, Byrn RA, Marsters SA, Gregory T, Groopman JE, Capon DJ. 1987. Blocking of HIV-1 infectivity by a soluble, secreted form of the CD4 antigen. Science 238:1704–1707. 10.1126/science.3500514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussey RE, Richardson NE, Kowalski M, Brown NR, Chang HC, Siliciano RF, Dorfman T, Walker B, Sodroski J, Reinherz EL. 1988. A soluble CD4 protein selectively inhibits HIV replication and syncytium formation. Nature 331:78–81. 10.1038/331078a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daar ES, Li XL, Moudgil T, Ho DD. 1990. High concentrations of recombinant soluble CD4 are required to neutralize primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:6574–6578. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin L, Stricher F, Misse D, Sironi F, Pugniere M, Barthe P, Prado-Gotor R, Freulon I, Magne X, Roumestand C, Menez A, Lusso P, Veas F, Vita C. 2003. Rational design of a CD4 mimic that inhibits HIV-1 entry and exposes cryptic neutralization epitopes. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:71–76. 10.1038/nbt768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin PF, Blair W, Wang T, Spicer T, Guo Q, Zhou N, Gong YF, Wang HG, Rose R, Yamanaka G, Robinson B, Li CB, Fridell R, Deminie C, Demers G, Yang Z, Zadjura L, Meanwell N, Colonno R. 2003. A small molecule HIV-1 inhibitor that targets the HIV-1 envelope and inhibits CD4 receptor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:11013–11018. 10.1073/pnas.1832214100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madani N, Perdigoto AL, Srinivasan K, Cox JM, Chruma JJ, LaLonde J, Head M, Smith AB, Sodroski JG., III 2004. Localized changes in the gp120 envelope glycoprotein confer resistance to human immunodeficiency virus entry inhibitors BMS-806 and #155. J. Virol. 78:3742–3752. 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3742-3752.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Q, Ma L, Jiang S, Lu H, Liu S, He Y, Strick N, Neamati N, Debnath AK. 2005. Identification of N-phenyl-N′-(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidin-4-yl)-oxalamides as a new class of HIV-1 entry inhibitors that prevent gp120 binding to CD4. Virology 339:213–225. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto C, Narumi T, Otsuki H, Hirota Y, Arai H, Yoshimura K, Harada S, Ohashi N, Nomura W, Miura T, Igarashi T, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. 2013. A CD4 mimic as an HIV entry inhibitor: pharmacokinetics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21:7884–7889. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narumi T, Arai H, Yoshimura K, Harada S, Hirota Y, Ohashi N, Hashimoto C, Nomura W, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. 2013. CD4 mimics as HIV entry inhibitors: lead optimization studies of the aromatic substituents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21:2518–2526. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narumi T, Ochiai C, Yoshimura K, Harada S, Tanaka T, Nomura W, Arai H, Ozaki T, Ohashi N, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. 2010. CD4 mimics targeting the HIV entry mechanism and their hybrid molecules with a CXCR4 antagonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20:5853–5858. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narumi T, Arai H, Yoshimura K, Harada S, Nomura W, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. 2011. Small molecular CD4 mimics as HIV entry inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19:6735–6742. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haim H, Si Z, Madani N, Wang L, Courter JR, Princiotto A, Kassa A, DeGrace M, Gee-Estrada K, Mefford M, Gabuzda D, Smith AB, Sodroski J., III 2009. Soluble CD4 and CD4-mimetic compounds inhibit HIV-1 infection by induction of a short-lived activated state. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000360. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon YD, Lalonde JM, Yang Y, Elban MA, Sugawara A, Courter JR, Jones DM, Smith AB, Debnath IIIAK, Kwong PD. 2014. Crystal structures of HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with NBD analogues that target the CD4-binding site. PLoS One 9:e85940. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaLonde JM, Elban MA, Courter JR, Sugawara A, Soeta T, Madani N, Princiotto AM, Kwon YD, Kwong PD, Schon A, Freire E, Sodroski J, Smith AB., III 2011. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of small molecule inhibitors of CD4-gp120 binding based on virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19:91–101. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.11.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaLonde JM, Kwon YD, Jones DM, Sun AW, Courter JR, Soeta T, Kobayashi T, Princiotto AM, Wu X, Schon A, Freire E, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Sodroski J, Madani N, Smith AB., III 2012. Structure-based design, synthesis, and characterization of dual hotspot small-molecule HIV-1 entry inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 55:4382–4396. 10.1021/jm300265j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalonde JM, Le-Khac M, Jones DM, Courter JR, Park J, Schon A, Princiotto AM, Wu X, Mascola JR, Freire E, Sodroski J, Madani N, Hendrickson WA, Smith AB., III 2013. Structure-based design and synthesis of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor exploiting X-ray and thermodynamic characterization. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 4:338–343. 10.1021/ml300407y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madani N, Schon A, Princiotto AM, Lalonde JM, Courter JR, Soeta T, Ng D, Wang L, Brower ET, Xiang SH, Kwon YD, Huang CC, Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Freire E, Smith AB, Sodroski J., III 2008. Small-molecule CD4 mimics interact with a highly conserved pocket on HIV-1 gp120. Structure 16:1689–1701. 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schon A, Madani N, Klein JC, Hubicki A, Ng D, Yang X, Smith AB, Sodroski J, III, Freire E. 2006. Thermodynamics of binding of a low-molecular-weight CD4 mimetic to HIV-1 gp120. Biochemistry 45:10973–10980. 10.1021/bi061193r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada Y, Ochiai C, Yoshimura K, Tanaka T, Ohashi N, Narumi T, Nomura W, Harada S, Matsushita S, Tamamura H. 2010. CD4 mimics targeting the mechanism of HIV entry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20:354–358. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura K, Harada S, Shibata J, Hatada M, Yamada Y, Ochiai C, Tamamura H, Matsushita S. 2010. Enhanced exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate neutralization epitopes through binding of CD4 mimetic compounds. J. Virol. 84:7558–7568. 10.1128/JVI.00227-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon YD, Finzi A, Wu X, Dogo-Isonagie C, Lee LK, Moore LR, Schmidt SD, Stuckey J, Yang Y, Zhou T, Zhu J, Vicic DA, Debnath AK, Shapiro L, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Sodroski JG, Kwong PD. 2012. Unliganded HIV-1 gp120 core structures assume the CD4-bound conformation with regulation by quaternary interactions and variable loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:5663–5668. 10.1073/pnas.1112391109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curreli F, Choudhury S, Pyatkin I, Zagorodnikov VP, Bulay AK, Altieri A, Kwon YD, Kwong PD, Debnath AK. 2012. Design, synthesis and antiviral activity of entry inhibitors that target the CD4-binding site of HIV-1. J. Med. Chem. 55:4764–4775. 10.1021/jm3002247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss A, Wiskocil RL, Stobo JD. 1984. The role of T3 surface molecules in the activation of human T cells: a two-stimulus requirement for IL 2 production reflects events occurring at a pre-translational level. J. Immunol. 133:123–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. 1998. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2855–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1896–1905. 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolchinsky P, Mirzabekov T, Farzan M, Kiprilov E, Cayabyab M, Mooney LJ, Choe H, Sodroski J. 1999. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J. Virol. 73:8120–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bjorndal A, Deng H, Jansson M, Fiore JR, Colognesi C, Karlsson A, Albert J, Scarlatti G, Littman DR, Fenyo EM. 1997. Coreceptor usage of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates varies according to biological phenotype. J. Virol. 71:7478–7487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Page KA, Landau NR, Littman DR. 1990. Construction and use of a human immunodeficiency virus vector for analysis of virus infectivity. J. Virol. 64:5270–5276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blish CA, Jalalian-Lechak Z, Rainwater S, Nguyen MA, Dogan OC, Overbaugh J. 2009. Cross-subtype neutralization sensitivity despite monoclonal antibody resistance among early subtype A, C, and D envelope variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 83:7783–7788. 10.1128/JVI.00673-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long EM, Rainwater SM, Lavreys L, Mandaliya K, Overbaugh J. 2002. HIV type 1 variants transmitted to women in Kenya require the CCR5 coreceptor for entry, regardless of the genetic complexity of the infecting virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 18:567–576. 10.1089/088922202753747914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulkarni SS, Lapedes A, Tang H, Gnanakaran S, Daniels MG, Zhang M, Bhattacharya T, Li M, Polonis VR, McCutchan FE, Morris L, Ellenberger D, Butera ST, Bollinger RC, Korber BT, Paranjape RS, Montefiori DC. 2009. Highly complex neutralization determinants on a monophyletic lineage of newly transmitted subtype C HIV-1 Env clones from India. Virology 385:505–520. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 79:10108–10125. 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307–312. 10.1038/nature01470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG, Sun C, Grayson T, Wang S, Li H, Wei X, Jiang C, Kirchherr JL, Gao F, Anderson JA, Ping LH, Swanstrom R, Tomaras GD, Blattner WA, Goepfert PA, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Delwart EL, Busch MP, Cohen MS, Montefiori DC, Haynes BF, Gaschen B, Athreya GS, Lee HY, Wood N, Seoighe C, Perelson AS, Bhattacharya T, Korber BT, Hahn BH, Shaw GM. 2008. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7552–7557. 10.1073/pnas.0802203105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Mokili JL, Muldoon M, Denham SA, Heil ML, Kasolo F, Musonda R, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Korber BT, Allen S, Hunter E. 2004. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science 303:2019–2022. 10.1126/science.1093137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Derdeyn CA, Morris L, Williamson C, Robinson JE, Decker JM, Li Y, Salazar MG, Polonis VR, Mlisana K, Karim SA, Hong K, Greene KM, Bilska M, Zhou J, Allen S, Chomba E, Mulenga J, Vwalika C, Gao F, Zhang M, Korber BT, Hunter E, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. 2006. Genetic and neutralization properties of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular env clones from acute and early heterosexually acquired infections in Southern Africa. J. Virol. 80:11776–11790. 10.1128/JVI.01730-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson C, Morris L, Maughan MF, Ping LH, Dryga SA, Thomas R, Reap EA, Cilliers T, van Harmelen J, Pascual A, Ramjee G, Gray G, Johnston R, Karim SA, Swanstrom R. 2003. Characterization and selection of HIV-1 subtype C isolates for use in vaccine development. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 19:133–144. 10.1089/088922203762688649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connor RI, Chen BK, Choe S, Landau NR. 1995. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology 206:935–944. 10.1006/viro.1995.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]