Abstract

The molecular epidemiology of 66 NDM-producing isolates from 2 Pakistani hospitals was investigated, with their genetic relatedness determined using repetitive sequence-based PCR (Rep-PCR). PCR-based replicon typing and screening for antibiotic resistance genes encoding carbapenemases, other β-lactamases, and 16S methylases were also performed. Rep-PCR suggested a clonal spread of Enterobacter cloacae and Escherichia coli. A number of plasmid replicon types were identified, with the incompatibility A/C group (IncA/C) being the most common (78%). 16S methylase-encoding genes were coharbored in 81% of NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

TEXT

With the worldwide spread of the NDM-1 gene and its variants (NDM-2 to NDM-8) (1, 2), molecular epidemiological studies of global isolates using various genotyping techniques are essential for gaining a better understanding of how this spread is occurring. India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are clearly major reservoir countries for blaNDM, with numerous factors, such as antibiotic selection pressure, contributing to this current situation (3, 4). This study examines a group of 66 NDM-1-producing isolates from Pakistan for their genetic relatedness, phylotype, plasmid replicon type, and plasmid transferability.

All isolates were acquired from stool samples from 37 distinct patients at two military hospitals in Rawalpindi, Pakistan (5). The samples were collected from inpatients (35%) and outpatients (65%). The isolates were tested for susceptibility to 17 antimicrobials using the Vitek 2 system. The MICs for meropenem, doripenem, fosfomycin, and amdinocillin were determined using a standard agar dilution methodology (5).

The isolates were reconfirmed for the presence of the carbapenem resistance gene blaNDM-1 by PCR, as previously described (6). PCR was also performed to detect blaOXA-48, blaOXA-23, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaKPC, blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV, blaTEM, blaOXA-1 group, AmpC β-lactamases, blaCMY-2, and the 16S rRNA methylase genes armA, rmtB, rmtC, and rmtF (6–9). The phylogenetic groups of Escherichia coli were determined using a multiplex (PCR)-based method (10).

Repetitive sequenced-based PCR (Rep-PCR)-based typing by the DiversiLab system (bioMérieux, Oakleigh, Australia) was used for assessing clonal relatedness. A cluster of closely related isolates was defined as isolates sharing >95% similarity and indistinguishable isolates of >97% (11, 12). PCR-based replicon typing analysis (PBRT) was performed to determine the plasmid incompatibility (Inc) groups for all Enterobacteriaceae isolates (13).

Ten genetically diverse E. coli isolates, based on different Rep-PCR profiles and phylogroups, were selected for transformation studies and typing by multilocus sequence typing (MLST). MLST included seven conserved housekeeping genes and was performed according to the E. coli MLST Database (see http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli).

The transferability of blaNDM-1-carrying plasmids was investigated by electroporation. Plasmid DNA was prepared and electroporated into the recipient TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), as previously described (6). Successful electrotransformants carrying blaNDM-1 were confirmed by PCR. The plasmid replicon type of the transformants acquiring blaNDM-1-carrying plasmids was confirmed by PBRT. Plasmid size was determined by performing S1 endonuclease (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) restriction digestion using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (14). PCR-amplified DNA probes of blaNDM-1 were labeled with digoxigenin nucleic acid (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Widespread dissemination of NDM-1 in Pakistan was first described in 2010 (15). In this study, we investigated the molecular epidemiology of a group of NDM-1-producing isolates from Pakistan, and we report here on the clonal relatedness of these isolates, providing an insight into the molecular characterization of blaNDM-1-carrying plasmids.

The majority of the NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates coharbored an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) gene, blaCTX-M-15 (70%). blaCMY-2 and the cooccurrence of 16S rRNA methylase genes encoding broad-spectrum aminoglycoside resistance, rmtB, rmtC, or armA, was detected in 47 (75%) isolates (Table 1). AmpC β-lactamase production coexisting with an ESBL was also high (n = 36 [73%]). The novel 16S rRNA methylase rmtF (16) was not detected; however, rmtB was found in 8 E. coli strains. A strong association between NDM-producing isolates harboring a 16S rRNA methylase-encoding gene has been well documented, particularly with rmtC. More recent studies in India, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Nepal have reported the carriage of rmtF among NDM-harboring isolates (9, 17–19). rmtB together with blaNDM is a rare association, although a recent outbreak of E. coli isolates in Bulgaria, harboring both blaNDM-1 and rmtB genes, raises new concerns for the acquisition of resistance determinants (20). Our results suggest that NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae from Rawalpindi, Pakistan, have acquired a broad spectrum of singular and distinct resistance genes.

TABLE 1.

Resistance genes and plasmid replicon types of NDM-1-producing isolates

| NDM-producing isolates (no.) | No. (%) of antibiotic resistance genes |

Plasmid replicon type(s) (no.) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactamasesa |

16S rRNA methylases |

||||||||

| blaCMY-2 | blaCTX-M-15 | blaSHV blaTEM | blaOXA-1 | rmtB | rmtC | rmtF | armA | ||

| Escherichia coli (30) | 26 (87) | 16 (53) | 0, 19 (63) | 9 (30) | 8 (27) | 20 (67) | 0 | 15 (50) | IncHI1 (10), IncI1 (2), IncL/M (2), IncN (4), IncFIA (5), IncFIB (6), IncY (2), IncA/C (25), IncFII (9) |

| Enterobacter cloacae (21) | 16 (76) | 21 (100) | 0, 20 (95) | 20 (95) | 0 | 15 (71) | 0 | 14 (67) | IncA/C (19), untypeable (2) |

| Citrobacter freundii (4) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 0, 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | IncA/C (2), IncFII (1), untypeable (1) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NDb |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (3) | 1 (33) | 3 (100) | 3 (100), 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 0 | 1 (33) | IncN (1), IncA/C (1), untypeable (1) | |

| Pseudocitrobacter faecalis (2) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0, 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | IncN (2) |

| Providencia rettgeri (2) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0, 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 2 (100) | IncA/C (1), IncN (2), IncY (1) |

| Citrobacter braakii (1) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0, 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | IncA/C (1) |

| Total no. of isolatesc | 49 (78) | 44 (70) | 3 (5), 46 (73) | 37 (59) | 8 (13) | 38 (60) | 0 | 33 (52) | IncA/C (49) |

All isolates were negative for blaOXA-48, blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaKPC.

ND, not determined.

A. baumannii excluded from this total.

The plasmid incompatibility types HI1, I1, L/M, N, FIA, FIB, Y, A/C, and FII were identified among the NDM-1-producing isolates (Table 1). Plasmid replicon typing revealed the dominance of two incompatibility groups, IncA/C (78%) and IncF (33%), with IncA/C occurring in multiple NDM-carrying species. IncA/C plasmids carrying blaNDM have been reported in Pakistan (21).

Of the 10 E. coli isolates subjected to electroporation, the blaNDM-1 plasmids in 4 isolates were successfully electroporated. Plasmid replicon typing of these transformants confirmed that blaNDM-1 resides on IncA/C-, IncN-, IncFIB-, and IncFII-type plasmids. These replicon types have been reported in Enterobacteriaceae in many regions of the world (4).

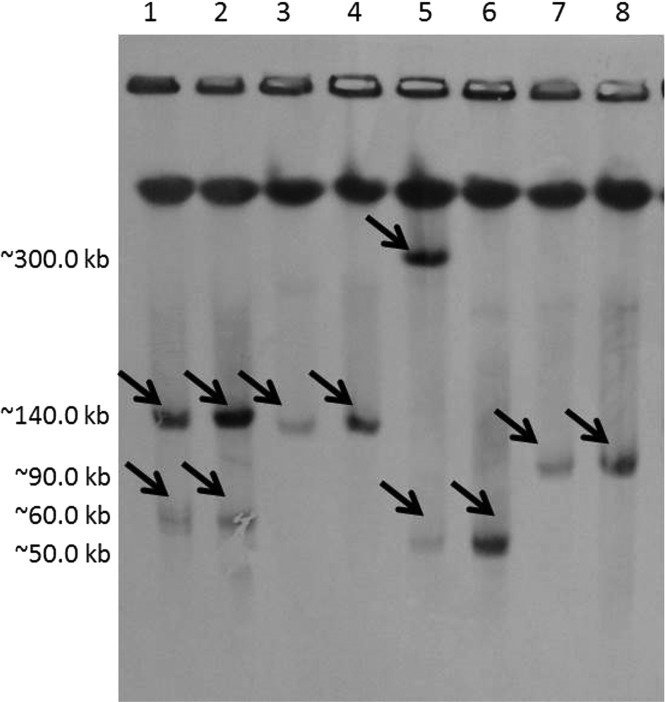

Southern hybridization (Fig. 1) of the E. coli donors and their transformants revealed blaNDM-1 plasmid sizes ranging from ∼50 kb to ∼350 kb. The majority of the blaNDM-1 plasmids were ∼140 kb in size. Among the 30 E. coli isolates, there was a predominance of the phylogenetic group B1 (57%), followed by phylotypes A (40%) and D (3%). It has been suggested that the distribution of E. coli phylotypes may be geographically dependent (22). Mushtaq et al. (23) found a prevalence of phylotype B1 among NDM isolates in Pakistan and no phylotype B2. Our study shows similar results.

FIG 1.

Southern blot hybridization of the PFGE gel with a specific blaNDM-1 probe. The black arrows indicate positive signals with the NDM-1 probe in each E. coli clinical isolate and its corresponding transformant. Lanes 1 to 8, PN1, PN1 TF1, PN7, PN7 TF1, PN14, PN14 TF1, PN18, and PN18 TF1, respectively.

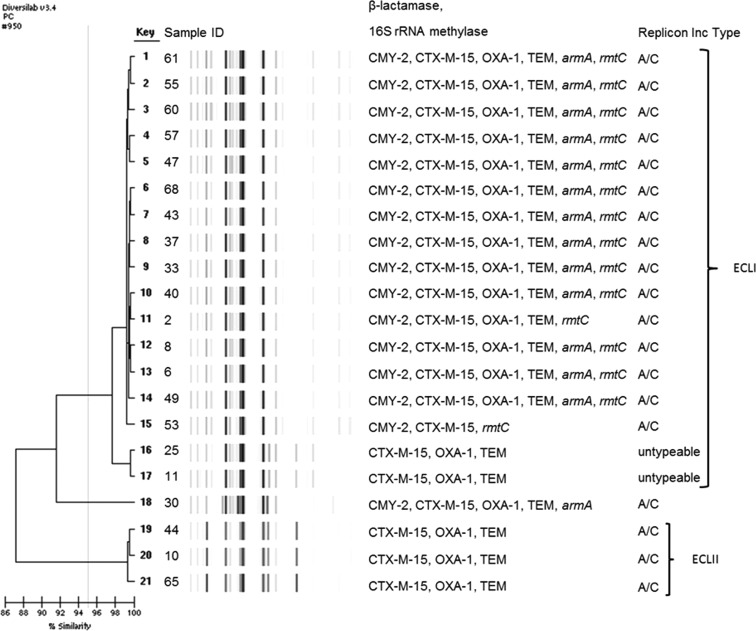

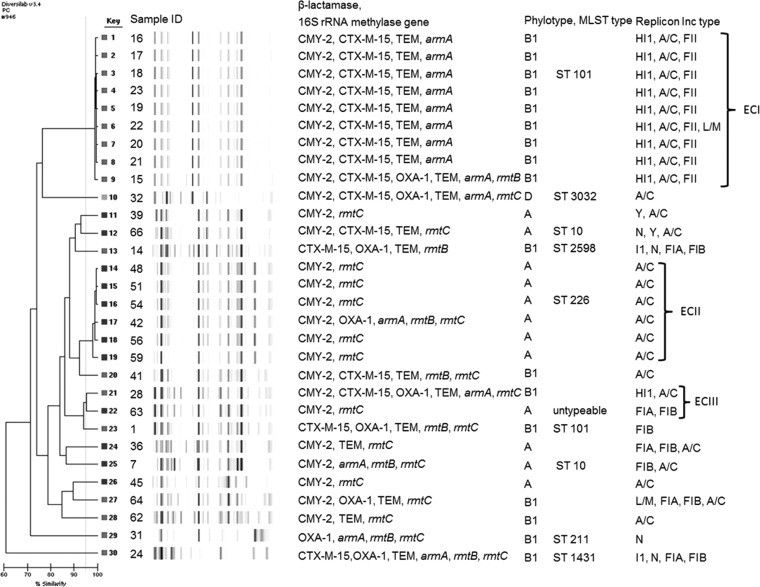

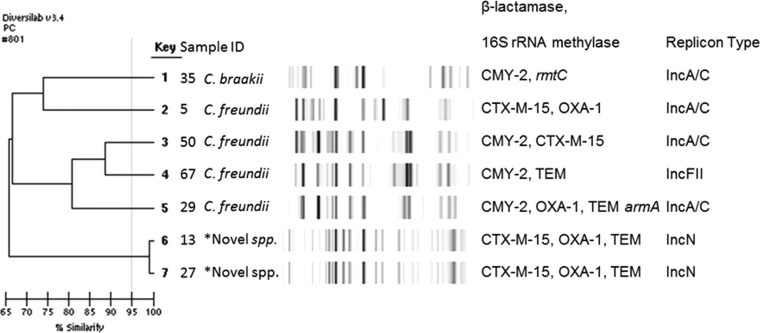

Rep-PCR revealed two dominant clones among Enterobacter cloacae, one large cluster (n = 17), designated ECLI, and one small cluster of three isolates (ECLII) (see Fig. 2). Three clonal types were observed among 17 E. coli isolates, and the remaining E. coli isolates were diverse (Fig. 3). The three Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were genetically diverse, while the three Acinetobacter baumannii isolates were considered identical (>99% similarity) (data not shown). Figure 4 shows the dendrogram for Citrobacter spp. and Pseudocitrobacter faecalis isolates (>99% similarity).

FIG 2.

Dendrogram analysis of DiversiLab Rep-PCR fingerprint of NDM-1-producing E. cloacae isolates.

FIG 3.

Dendrogram analysis of DiversiLab Rep-PCR fingerprint of NDM-1-producing E. coli isolates by phylotype.

FIG 4.

Dendrogram analysis of DiversiLab Rep-PCR fingerprint of NDM-1-producing Citrobacter isolates. *, novel species, Pseudocitrobacter faecalis.

MLST differentiated the 10 representative E. coli strains into seven sequence types and one unknown sequence type (ST) (untypeable). The sequence types included ST10 (n = 2), ST101 (n = 2), and single isolates representing STs 211, 226, 1431, 2598, and 3032. MLST studies on NDM-1-producing E. coli in the literature provide an incomplete and heterogeneous global distribution, suggesting a nonclonal pattern of spread for blaNDM-1 (24). In this study, the clinical isolates of E. coli representing STs 211, 226, 1431, 2598, and 3032 to our knowledge have not been reported in NDM-1-producing E. coli.

There were a number of limitations in our study, including the lack of clinical patient data and using fecal samples from 2 hospitals at a single point in time. It is difficult in this respect to obtain a clear epidemiological picture of NDM-producing isolates more widely in Pakistan.

The spread of blaNDM-1 is frequently associated with common and highly promiscuous plasmids resulting in a diverse range of species and clones harboring blaNDM-1. However, the molecular epidemiology of our study may indicate that blaNDM-1 additionally disseminates via dominant clones. The potential role of such dominant clones as a factor of blaNDM-1 spread may be underrepresented due to the lack of large-scale surveillance and molecular epidemiological studies monitoring blaNDM-1 dissemination. In this scenario, we can see a situation in which a single clone of NDM-1 may become epidemic or pandemic.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Göttig S, Hamprecht AG, Christ S, Kempf VA, Wichelhaus TA. 2013. Detection of NDM-7 in Germany, a new variant of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase with increased carbapenemase activity. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:1737–1740. 10.1093/jac/dkt088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tada T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Dahal RK, Sah MK, Ohara H, Kirikae T, Pokhrel BM. 2013. NDM-8 metallo-β-lactamase in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strain isolated in Nepal. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2394–2396. 10.1128/AAC.02553-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P. 2013. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: overview of a major public health challenge. Med. Mal. Infect. 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wailan AM, Paterson DL. 2013. The spread and acquisition of NDM-1: a multifactorial problem. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 12:91–115. 10.1586/14787210.2014.856756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry JD, Naqvi SH, Mirza IA, Alizai SA, Hussain A, Ghirardi S, Orenga S, Wilkinson K, Woodford N, Zhang J, Livermore DM, Abbasi SA, Raza MW. 2011. Prevalence of faecal carriage of Enterobacteriaceae with NDM-1 carbapenemase at military hospitals in Pakistan, and evaluation of two chromogenic media. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2288–2294. 10.1093/jac/dkr299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidjabat H, Nimmo GR, Walsh TR, Binotto E, Htin A, Hayashi Y, Li J, Nation RL, George N, Paterson DL. 2011. Carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae due to the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:481–484. 10.1093/cid/ciq178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirel L, Héritier C, Tolün V, Nordmann P. 2004. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:15–22. 10.1128/AAC.48.1.15-22.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muzaheed, Doi Y, Adams-Haduch JM, Endimiani A, Sidjabat HE, Gaddad SM, Paterson DL. 2008. High prevalence of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae among inpatients and outpatients with urinary tract infection in southern India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1393-1394. 10.1093/jac/dkn109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidalgo L, Hopkins KL, Gutierrez B, Ovejero CM, Shukla S, Douthwaite S, Prasad KN, Woodford N, Gonzalez-Zorn B. 2013. Association of the novel aminoglycoside resistance determinant RmtF with NDM carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae isolated in India and the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:1543–1550. 10.1093/jac/dkt078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558. 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brolund A, Hæggman S, Edquist PJ, Gezelius L, Olsson-Liljequist B, Wisell KT, Giske CG. 2010. The DiversiLab system versus pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: characterisation of extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. Methods 83:224–230. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitout JDD, Campbell L, Church DL, Wang PW, Guttman DS, Gregson DB. 2009. Using a commercial DiversiLab semiautomated repetitive sequence-based PCR typing technique for identification of Escherichia coli clone ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1212–1215. 10.1128/JCM.02265-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:219–228. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL, Adams-Haduch JM, Ewan L, Pasculle AW, Muto CA, Tian GB, Doi Y. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary medical center in western Pennsylvania. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4733-4739. 10.1128/AAC.00533-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, Chaudhary U, Doumith M, Giske CG, Irfan S, Krishnan P, Kumar AV, Maharjan S, Mushtaq S, Noorie T, Paterson DL, Pearson A, Perry C, Pike R, Rao B, Ray U, Sarma JB, Sharma M, Sheridan E, Thirunarayan MA, Turton J, Upadhyay S, Warner M, Welfare W, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:597–602. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galimand M, Courvalin P, Lambert T. 2012. RmtF, a new member of the aminoglycoside resistance 16S rRNA N7 G1405 methyltransferase family. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3960–3962. 10.1128/AAC.00660-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman M, Shukla SK, Prasad KN, Ovejero CM, Pati BK, Tripathi A, Singh A, Srivastava AK, Gonzalez-Zorn B. 2014. Prevalence and molecular characterisation of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases NDM-1, NDM-5, NDM-6 and NDM-7 in multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from India. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 44:30–37. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin JE, Peirano G, Peer AK, Govind CN, Pitout JD. 2014. NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae from South Africa: moving towards endemicity? Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 79:378–380. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tada T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Dahal RK, Mishra SK, Ohara H, Shimada K, Kirikae T, Pokhrel BM. 2013. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates with various combinations of carbapenemases (NDM-1 and OXA-72) and 16S rRNA methylases (ArmA, RmtC and RmtF) in Nepal. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 42:372–374. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poirel L, Savov E, Nazli A, Trifonova A, Todorova I, Gergova I, Nordmann P. 2014. Outbreak caused by NDM-1- and RmtB-producing Escherichia coli in Bulgaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58:2472–2474. 10.1128/AAC.02571-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poirel L, Dortet L, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. 2011. Genetic features of blaNDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5403–5407. 10.1128/AAC.00585-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen KL, Dynesen P, Larsen P, Frimodt-Møller N. 2014. Faecal Escherichia coli from patients with E. coli urinary tract infection and healthy controls who have never had a urinary tract infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 63:582–589. 10.1099/jmm.0.068783-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mushtaq S, Irfan S, Sarma JB, Doumith M, Pike R, Pitout J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2011. Phylogenetic diversity of Escherichia coli strains producing NDM-type carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2002–2005. 10.1093/jac/dkr226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bushnell G, Mitrani-Gold F, Mundy LM. 2013. Emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase type 1-producing Enterobacteriaceae and non-Enterobacteriaceae: global case detection and bacterial surveillance. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 17:e325–333. 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]