ABSTRACT

The fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcriptase (RT) has been a subject of intensive investigation. The mutation frequencies for the purified enzyme in vitro vary widely but are typically in the 10−4 range (per nucleotide addition), making the enzyme severalfold less accurate than most polymerases, including other RTs. This has often been cited as a factor in HIV's accelerated generation of genetic diversity. However, cellular experiments suggest that HIV does not have significantly lower fidelity than other retroviruses and shows a mutation frequency in the 10−5 range. In this report, we reconcile, at least in part, these discrepancies by showing that HIV RT fidelity in vitro is in the same range as cellular results from experiments conducted with physiological (for lymphocytes) concentrations of free Mg2+ (∼0.25 mM) and is comparable to Moloney murine leukemia virus (MuLV) RT fidelity. The physiological conditions produced mutation rates that were 5 to 10 times lower than those obtained under typically employed in vitro conditions optimized for RT activity (5 to 10 mM Mg2+). These results were consistent in both commonly used lacZα complementation and steady-state fidelity assays. Interestingly, although HIV RT showed severalfold-lower fidelity under high-Mg2+ (6 mM) conditions, MuLV RT fidelity was insensitive to Mg2+. Overall, the results indicate that the fidelity of HIV replication in cells is compatible with findings of experiments carried out in vitro with purified HIV RT, providing more physiological conditions are used.

IMPORTANCE Human immunodeficiency virus rapidly evolves through the generation and subsequent selection of mutants that can circumvent the immune response and escape drug therapy. This process is fueled, in part, by the presumably highly error-prone HIV polymerase reverse transcriptase (RT). Paradoxically, results of studies examining HIV replication in cells indicate an error frequency that is ∼10 times lower than the rate for RT in the test tube, which invokes the possibility of factors that make RT more accurate in cells. This study brings the cellular and test tube results in closer agreement by showing that HIV RT is not more error prone than other RTs and, when assayed under physiological magnesium conditions, has a much lower error rate than in typical assays conducted using conditions optimized for enzyme activity.

INTRODUCTION

Reverse transcriptase (RT), the DNA polymerase of retroviruses, is a key target for highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) directed against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (for a recent review, see reference 1). HIV RT is a heterodimer with p66 and p51 subunits and, like other RTs, possesses both DNA polymerase and RNase H activities (2). Both activities are divalent cation dependent, and the polymerase active site contains two divalent cation binding sites. Models for one or two cation binding sites have also been proposed for RNase H (3–9).

Much of what is known about the biochemical properties of HIV RT is based on in vitro assays with Mg2+ (∼5 to 10 mM) and deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP; 25 to 100 μM) concentrations optimized for enzyme activity, which are much greater than the available levels in cells. Estimates for free Mg2+ concentrations in cells vary considerably, from less than 0.25 mM to as high as about 2 mM (10–14). However, results indicate that free Mg2+ concentrations are low in the brain (0.21 to 0.24 mM) (15) and, most relevantly, in human lymphocytes (∼0.25 mM), which are one of the main HIV-1 targets (13, 16). Likewise, deoxyribonucleotide concentrations are also relatively low (5 μM in T cells [17, 18]).

Like other biochemical properties, RT fidelity has typically been examined using conditions optimized for polymerase activity and with lacZα complementation assays (19) or steady-state and pre-steady-state misincorporation and mismatch extension assays (reviewed in reference 20). Magnesium concentrations of 5 to 10 mM (or greater) are often used in these assays. Fidelity measured in vitro (20–29) is typically ∼5- to 10-fold lower than the cellular fidelity (30–32). Explanations for this greater fidelity in cells range from cellular or viral proteins (in addition to RT) that participate in reverse transcription, small-molecule components in cells, or special conditions in the virion, but the actual cause has remained unknown, as have other effects that the cell environment may have on the reverse transcription process (see reference 33 for a discussion of this topic). Interestingly, HIV RT displays lower fidelity in vitro than other reverse transcriptases (e.g., those of Moloney murine leukemia virus [MuLV] and avian myeloblastosis virus [AMV]), yet cellular fidelities for these viruses are comparable (20, 34). In this study, we used Mg2+ concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 6 mM in both lacZα complementation and steady-state misincorporation or mismatch extension assays. In both assay types, HIV RT fidelity was severalfold higher with a low, more physiological Mg2+ concentration (0.25 mM). In contrast to that of HIV RT, the fidelity of MuLV RT was not sensitive to Mg2+ concentrations, and it was approximately equal to that of HIV RT when assayed under more physiological conditions. These results suggest that the higher fidelity of HIV during cellular infection versus classical in vitro fidelity assays is due, at least in part, to the lower Mg2+ concentration in cells. They also challenge the notion that HIV RT has relatively low fidelity in comparison to those of other RTs and that RT infidelity allows HIV to evolve faster than other viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP), T3 RNA polymerase, high-fidelity (PvuII and EcoRI) and other restriction enzymes, T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK), and MuLV RT were from New England BioLabs. DNase-free RNase, ribonucleotides, and deoxyribonucleotides were obtained from Roche. RNase-free DNase I was from United States Biochemical. The rapid DNA ligation kit, RNasin (RNase inhibitor), and the ϕX174 HinfI digest DNA ladder were from Promega. Radiolabeled compounds were from PerkinElmer. Pfu DNA polymerase was from Stratagene. DNA oligonucleotides were from Integrated DNA Technologies. G-25 spin columns were from Harvard Apparatus. RNeasy RNA purification and plasmid DNA miniprep kits were from Qiagen. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) was from Denville Scientific, Inc. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and media were from Gibco, Life Technologies. All other chemicals were obtained from Fisher Scientific, VWR, or Sigma. HIV RT (from strain HXB2) was prepared as described previously (35). The HIV RT clone was a generous gift from Michael Parniak (University of Pittsburgh). Aliquots of HIV RT were stored frozen at −80°C, and fresh aliquots were used for each experiment.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Denaturing polyacrylamide gels (6, 8, and 16%, wt/vol), native polyacrylamide gels (15%, wt/vol), and 0.7% agarose gels were prepared and run as described previously (36).

Preparation of RNA for the PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay and RNA-DNA and RNA-DNA hybridization.

Transcripts (∼760 nucleotides [nt]) were prepared with T3 RNA polymerase and hybrids were prepared at a 2:1 5′-, 32P-labeled primer/template ratio as previously described (37).

Primer extension reactions for the PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay.

For RNA-directed DNA synthesis, the ∼760-nucleotide RNA template was hybridized to a radiolabeled 25-nucleotide DNA primer (5′-GCGGGCCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAG-3′). Full extension produced a 199-nucleotide final product (see Fig. 1A and 5). The primer-template complex was preincubated in 48 μl of buffer (see below) for 3 min at 37°C. The reaction was initiated by addition of 2 μl of 5 μM HIV RT in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 80 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 10% glycerol, and incubation was continued for 30 min. The final concentrations of reaction components were 200 nM HIV RT (or MuLV RT), 25 nM template, 50 nM primer, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 80 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.4% glycerol, and 0.4 U/μl of RNasin. Concentrations of MgCl2 (0.25, 2, or 6 mM) and dNTPs (5 or 100 μM each) were as indicated below and in the figure legends. The final pH of the reactions was 7.7 unless otherwise indicated. After incubations, 1 μl of DNase-free RNase was added and the sample was heated to 65°C for 5 min. Typically, two reaction mixtures for each condition were combined and material was recovered by standard phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7) and 2× loading buffer (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8], 0.25% each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol), and products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide-urea gels (19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide). Fully extended 199-nucleotide DNA was located using a phosphorimager (Fujifilm FLA5100) and recovered by the crush and soak method (36) in 500 μl of elution buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7). After overnight elution, this material was passed through a 0.45-μm syringe filter and recovered by ethanol precipitation after addition of a 10% volume of 3 M sodium acetate (NaOAc; pH 7) and 50 μg of glycogen. After centrifugation, the pellets were vigorously washed with 500 μl of 70% ethanol to remove any traces of EDTA that may have carried over from the gel and potentially interfered with the second round of synthesis. The recovered DNA was hybridized to another 20-nucleotide radiolabeled DNA primer (5′-AGGATCCCCGGGTACCGAGC-3′) with 10-fold-greater specific activity than the primer used for round 1, and a second round of DNA synthesis was performed as described above except that the reaction volume was 25 μl. Conditions for MgCl2, dNTPs, and pH were identical in the RNA and DNA template reactions. Reactions were terminated with an equal volume of 2× loading buffer, and products were gel purified as described above but on an 8% gel. The gel was run far enough to efficiently separate the 199-nucleotide templates from the 162-nucleotide full extension product of round 2.

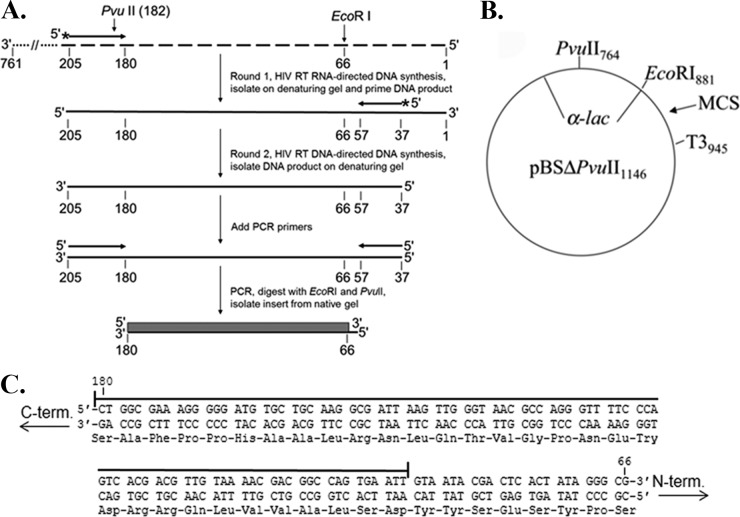

FIG 1.

PCR-based lacZα complementation system used to determine the fidelity of HIV RT. (A) An overview of the procedure used to assess polymerase fidelity is presented. RNAs are indicated by broken lines and DNAs by solid lines. Primers have arrowheads at the 3′ end. The ∼760-nucleotide template RNA used as the initial template for HIV RT RNA-directed DNA synthesis is shown at the top with the 3′ and 5′ ends indicated. The positions of PvuII and EcoRI restriction sites are indicated for reference to the vector. The filled box at the bottom of is the 115-base region of the lacZα gene that was scored in the assay. Details for specific steps are provided in Materials and Methods. (B) Plasmid pBSM13ΔPvuII1146 is shown. Relevant sites on the plasmid are indicated; numbering is based on that for the parent plasmid (pBSM13+ [Stratagene]). (C) The nucleotide and amino acid sequences for the 115-base region of the lacZα gene that was scored in the assay are shown. Both strands of the DNA plasmid are shown since HIV RT synthesis was performed in both directions (see panel A). A line is drawn above the 92 nt that are in the detectable area for substitution mutations, while frameshifts can be detected over the entire 115-nucleotide region. Based on a previous cataloging of mutations in this gene (19), the assay can detect 116 different substitutions (33.6% of the 345 possible substitutions in the 115-nucleotide sequence) and 100% of the frameshift mutations.

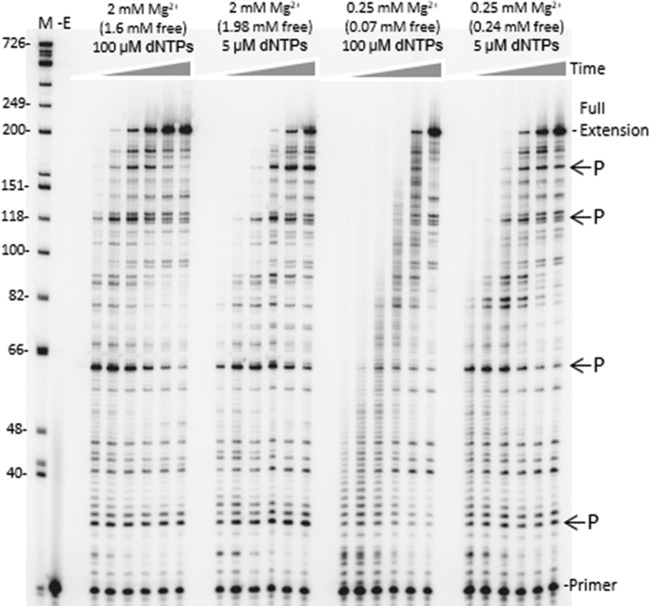

FIG 5.

Time course of HIV RT synthesis on the ∼760-nucleotide RNA template used in the PCR-based α complementation assay. Shown is an autoradiogram with extension of a 20-nucleotide 5′-, 32P-end-labeled DNA primer on the RNA template used for round 1 synthesis by HIV RT (see Fig. 1). Full extension of the primer resulted in a 199-nucleotide product. A DNA ladder with nucleotide size positions is shown on the left. Concentrations of total and free Mg2+ and dNTPs are indicated above each lane. Positions of some prominent DNA synthesis pause sites (P) are indicated on the right. Reactions were performed for (1eft to right) 15 s, 30 s, 1 min, 2 min, 4 min, or 8 min under each condition. A no-enzyme control (−E) is also shown. Refer to Materials and Methods for details.

PCR for the PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay.

The round 2 DNA (50% of recovered material) produced in the above-described step by reverse transcription was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-GCGGGCCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAG-3′ and 5′-AGGATCCCCGGGTACCGAGC-3′. Reactions were performed and processed as previously described except that restriction digestion was with 30 U each of high-fidelity EcoRI and PvuII in 50 μl of NEB buffer 3 for 2 h at 37°C (37).

Preparation of vector for PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay.

Thirty micrograms of plasmid pBSΔPvuII1146 (38)was doubly digested with 50 U each of high-fidelity EcoRI and PvuII in 100 μl using the supplied buffer and protocol. After 3 h, DNA was recovered by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and then treated with 20 U of CIP for 2 h at 37°C in 100 μl of the supplied NEB restriction digest buffer 3. Dephosphorylated vector was recovered by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and quantified using the absorbance at 260 nm. The quality of the vectors for the fidelity assay was assessed in two ways: (i) ligation (see below) of the vector preparation in the absence of insert and (ii) religation of the vector preparation and PvuII-EcoRI-cleaved fragment (recovered from agarose gels after cleavage of pBSΔPvuII1146 but before dephosphorylation as described above). Vectors from method i that did not produce any white or faint blue colonies and very few blue colonies in the complementation assay (see below) and those producing colony mutation frequencies of less than ∼0.003 (1 white or faint blue colony in ∼333 total) in method ii were used in the fidelity assays.

Ligation of PCR fragments into vectors and transformation for the PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay.

The cleaved vector (50 ng, ∼0.025 pmol) and insert fragments (0.05 pmol) were ligated at a 1:2 (vector/insert) molar ratio using a rapid DNA ligation kit. Ligation and transformation of Escherichia coli GC5 bacteria were carried out as previously described (37). White or faint blue colonies were scored as harboring mutations, while blue colonies were considered nonmutated. Any colonies that were questionable with respect to being either faint blue or blue were picked and replated with an approximately equal amount of blue colony stock. Observing the faint blue colony in a background of blue colonies made it easy to determine if the colony was faint blue rather than blue.

Gapped plasmid-based based lacZα complementation fidelity assay.

The gapped version of the plasmid pSJ2 was prepared as described previously (39). A 1 nM concentration of the gapped plasmid was filled by 100 nM RT at 37°C in 20 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 80 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 2 μg of bovine serum albumin, and various concentrations of dNTPs and MgCl2 (as indicated in the figure legends). The reaction pH was 7.7. Reactions with 2 mM Mg2+ (100 μM or 5 μM dNTPs) were carried out for 30 min, and reactions with 0.25 mM Mg2+ were performed for 4 h. Reactions were terminated by heating at 65°C for 15 min. After confirming complete extension by restriction digestion analysis (39), ∼1 μl of the remaining original mixture was transformed into E. coli GC5 cells. The colony mutation frequency (CMF) was determined using blue-white screening as described above.

Mismatched primer extension assays.

The approach used for these assays was based on previous results (40). The template (5′-GGGCGAATTTAG[G/C]TTTTGTTCCCTTTAAGGGTTAATTTCGAGCTTGG-3′) used in these assays was a modified version of the template originally described in reference 41. The underlined nucleotides in brackets indicate that templates with either a G or C at this position were used. The DNA primer (5′-TAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAACAAAAX-3′) used in the assays was 5′ radiolabeled and hybridized to the template at a 1:1 ratio as described above. The “X” at the 3′ end of the primer denotes either G, A, T, or C (see Fig. 3). Matched or mismatched primer templates (14 nM final) were incubated for 3 min at 37°C in 10.5 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 80 mM KCl, various concentrations of MgCl2, and increasing concentrations of the next correct dNTP substrate (dCTP for this template). The reaction pH was 7.7. Reactions were initiated by adding 2 μl of HIV RT (2 nM final concentration) and terminated by adding 2× loading buffer. All reactions involving matched primer-templates were carried out for 2 min. Reactions with mismatched primer-templates were carried out for 5 min (0.5, 1, 2, and 6 mM free Mg2+ reactions). At 0.25 mM Mg2+, mismatched primer-templates with a C·C or G·A were extended for 20 min, and all other mismatches were extended for 15 min. The reaction products were then electrophoresed on 16% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, dried, and imaged using a Fujifilm FLA5100 phosphorimager. Steady-state kinetic parameters Km and Vmax were then calculated as described below. The amount of free Mg2+ in each reaction was adjusted according to the dNTP concentration because dNTPs are the major chelators of Mg2+ in the reactions. The concentration of free Mg2+ was calculated using the formula

where Et, Dt, and [ED] represent the concentration of total Mg2+, total dNTP, and Mg2+ bound to the dNTPs, respectively. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for dNTP and Mg2+ was assumed to be the same as that of ATP (KD = 8.9 × 10−6 M).

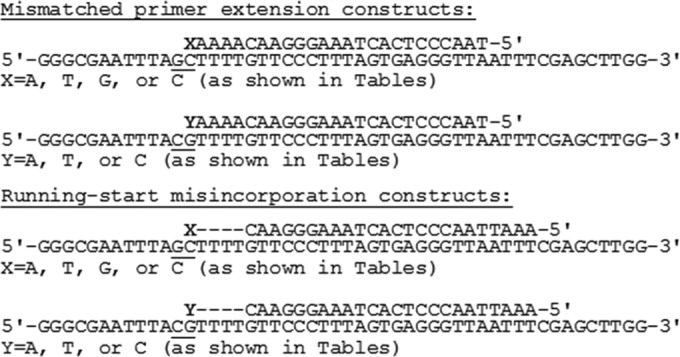

FIG 3.

Constructs used in mismatched primer extension and running-start misincorporation assays. The sequence of the DNA constructs used in each assay type is shown. The underlined nucleotides show the only differences between the two templates. Only one primer was used in the running-start assays, and it terminated at the 3′ C nucleotide before the dashes. The four dashes indicate the 4 A nucleotides that must be incorporated before RT incorporates the target nucleotide (denoted by X or Y).

Running-start misincorporation assays.

The approach used for running-start misincorporation assays was based on previous results (42). Reactions were performed as described above using the same template but with a primer (5′-GAAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAAC-3′) (see Fig. 3) which does not have the last 5 nt at the 3′ end and has 5 additional bases at the 5′ end. Unlike mismatch extension assays, all reactions were performed for 3 min at 37°C. The nucleotide directed by the homopolymeric T run on the template running (dATP) was kept at a constant saturating concentration (55 μM) and the nucleotide to be misinserted (for example, dTTP for measuring C-T misinsertion kinetics) was added at increasing concentrations in these reactions. Reactions were resolved and processed as described above.

Velocity measurements and calculation of Vmax and Km for steady-state assays and calculation of extension rates for RNA-directed DNA synthesis in the PCR-based fidelity assay.

Velocity measurement and calculation of Vmax and Km were conducted as described previously for mismatch extension (40) and running-start assays (42). Extension rate determinations for DNA synthesis on the 760-nucleotide RNA template were performed as described previously (43).

RESULTS

HIV RT shows greater fidelity with low Mg2+ in the PCR-based and plasmid-based lacZα complementation fidelity assays.

Both PCR and plasmid-based lacZα complementation assays were used to measure the fidelity of HIV RT. The PCR-based assay was a modified version of an assay used previously to examine the fidelity of poliovirus 3Dpol (37, 44) (Fig. 1). The 115-nucleotide region screened for mutations is shown in Fig. 1C. All frameshift mutations and several substitutions (see legend to Fig. 1) in this region can be detected in the assay (19). The assay essentially mimics the reverse transcription process, since both RNA- and DNA-directed RT synthesis steps are performed. As two rounds of synthesis are performed over the same 115-nucleotide region, the assay actually scores 230 total nt. Although there are several steps at which background mutations can be introduced, most of the background can be accounted for by performing a control in which plasmid DNA is PCR amplified to produce an insert identical to those produced in the complete assay. These inserts should comprise all error sources except the errors derived from HIV RT and T3 RNA polymerase. In our assays, an average background colony mutation frequency (CMF; number of white or faint blue colonies divided by total number of colonies) of 0.0021 ± 0.0008 (mean ± standard deviation) was obtained for the 16 experiments performed (Table 1). This corresponds to 1 white or faint blue colony in every ∼500 colonies. This background is higher than that in some phage-based assays (19, 25, 28) but comparable to that in others (45, 46).

TABLE 1.

Colony mutation frequencies for various Mg2+ and dNTP concentrations in PCR-based lacZα complementation assay

| Expt no.a | Background CMFb,c | Mutation data under indicated conditions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV RT |

MuLV RT |

|||||||

| 6 mM MgCl2 (5.6 mM free), 100 μM dNTPsc | 2 mM MgCl2 (1.98 mM free), 5 μM dNTPsc | 2 mM MgCl2 (1.6 mM free), 100 μM dNTPsc | 0.25 mM MgCl2 (0.24 mM free), 5 μM dNTPsc | 0.25 mM MgCl2 (0.07 mM free), 100 μM dNTPsc | 6 mM MgCl2 (5.6 mM free), 100 μM dNTPsc,d | 0.25 mM MgCl2 (0.24 mM free), 5 μM dNTPsc,d | ||

| 1 | 6/4,150, 1.4 | 32/3,637, 8.8 (7.4) | ||||||

| 2 | 6/4,600, 1.3 | 37/4,281, 6.9 (5.6) | ||||||

| 3 | 5/1,967, 2.5 | 27/1,961, 14 (12) | ||||||

| 4 | 13/4,560, 2.9 | 51/4,583, 11 (8.1) | ||||||

| 5 | 4/5,714, 0.7 | 30/10,362, 2.9 (2.2) | ||||||

| 6 | 24/8,276, 2.9 | 12/2,597, 4.6 (1.7) | ||||||

| 7 | 2/1,153, 1.7 | 16/2,137, 7.4 (5.7) | 6/2,164, 2.7 (1.0) | |||||

| 8 | 4/4,565, 0.8 | 38/8,050, 4.7 (3.9) | 30/10,362, 2.8 (2.0) | |||||

| 9 | 5/1,605, 3.0 | 10/1,041, 9.6 (6.6) | 13/1,354, 9.6 (6.6) | |||||

| 10 | 7/2,942, 2.4 | 26/3,318, 7.8 (5.4) | 13/3,585, 3.6 (1.2) | |||||

| 11 | 6/2,036, 2.9 | 10/1,358, 6.4 (3.5) | 5/1,310, 3.8 (0.9) | |||||

| 12 | 13/3,691, 3.5 | 20/2,224, 8.9 (5.5) | 6/1,503, 4.0 (0.5) | |||||

| 13 | 6/2,608, 2.3 | 16/1,639, 9.8 (7.5) | ||||||

| 14 | 6/2,998, 2.0 | 5/1,323, 3.8 (1.8) | 8/1,622, 4.9 (2.9) | |||||

| 15 | 7/2,464, 2.8 | 23/3,720, 6.2 (3.4) | 20/3,402, 5.9 (3.1) | |||||

| 16 | 4/2,611, 1.5 | 7/1,800, 3.9 (2.4) | 9/2,255, 4.0 (2.5) | |||||

| Avg ± SDe | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 10 ± 3.1 (8.3 ± 2.7) | 7.2 ± 2.4 (5.4 ± 1.3) | 8.5 ± 1 (5.7 ± 1.5) | 3.3 ± 0.9 (1.7 ± 0.5) | 3.8 ± 0.2 (0.9 ± 0.4) | 4.9 ± 0.9 (2.5 ± 0.8) | 4.9 ± 1.0 (2.8 ± 0.3) |

| P valuef | 0.157 | 0.110 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.019 | ||

| Relative fidelityg | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 9.2h | 3.3 | 3.0 | |

Independent experiments performed at different times. In typical experiments, 1,500 to 3,500 colonies were scored for each condition.

In background assays, plasmid pBSM13ΔPvuII (Fig. 1B) was used as a template in PCRs to generate the insert that was scored in the assays. See Results for a discussion of the background calculation. Numbers shown are the colony mutation frequency (CMF, ×10−3), defined as white plus faint blue colonies divided by total colonies. Refer to Results and Materials and Methods for details.

The number of white plus faint blue colonies/total number of colonies is shown, followed by the colony mutation frequency (×10−3) for experiments under the listed conditions; this frequency minus the background frequency from column two is in parentheses.

Assays were performed with MuLV RT from New England Biolabs. All other reactions were with HIV RT.

Averages ± standard deviations from the experiments in the column are shown. Averages ± standard deviations of the CMF value minus the background frequency from the listed experiments are in parentheses.

Values were calculated using a standard Student t test and the background subtracted values from each condition. All values were scored against that at 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP.

All values are relative to the 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP average background CMF (8.3 × 10−3). The 0.0083 value was divided by the average CMF minus the background value for each condition to determine relative fidelity. Higher numbers indicate greater fidelity.

CMF values for this condition were on average less than 2 times the background. Hence, the values are near the limits of this assay with respect to quantitative reliability.

In the PCR-based assay, in vitro conditions that maximize RT activity (6 mM total Mg2+/100 μM dNTPs) consistently showed the highest CMF, with about 1 in every 120 colonies (CMF of 0.0083 after background subtraction) showing mutations (Table 1). Decreasing the total Mg2+ concentration to 2 mM produced a modest (less than 2-fold) decrease in CMF at both 100 μM and the more physiological 5 μM dNTP concentration (see the introduction), indicating a small increase in fidelity. However, statistical analysis (P values in Table 1) suggested that there was not a reliably significant difference between results at 2 mM and 6 mM Mg2+. The results at 2 mM Mg2+ also suggest that the total dNTP concentration in the reactions is not a major determinant of fidelity, as there was no difference in CMFs between the 5 and 100 μM conditions. In contrast, a highly significant (P = 0.003) increase in fidelity, about 5-fold, over that in the 6 mM reactions was observed with 0.25 mM total Mg2+ and 5 μM dNTP. Reactions with 0.25 mM total Mg2+ and 100 μM dNTPs produced about a 9-fold increase in fidelity. Note that under this condition, free Mg2+ in the reactions was at only 0.07 mM. However, the CMFs were, on average, less than twice the assay background. Hence, although it is tempting to attribute the further increased fidelity to the very low Mg2+ concentration (0.07 mM) in these reactions, assay limitations preclude this conclusion. Overall, the results show that low concentrations of free Mg2+ (∼0.25 mM) reported for lymphocytes (see the introduction) dramatically increase the fidelity of HIV RT.

Other retroviral reverse transcriptases, including MuLV RT, have been reported to have higher fidelity than HIV RT (see the introduction and Discussion) in vitro. The fidelity of MuLV RT was tested in the PCR-based assay at 6 mM total Mg2+/100 μM dNTP or 0.25 mM total Mg2+/5 μM dNTP. Consistent with previous results, MuLV RT was ∼3-fold more accurate than HIV RT with the higher Mg2+ concentration commonly used in in vitro reactions (Table 1). However, unlike for HIV RT, there was no improvement in fidelity under the low-Mg2+ condition. Under this condition, the fidelities of the two RTs were essentially the same.

To further confirm results with the PCR-based assay, a second gapped plasmid-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay was performed. This assay is similar to the phage-based lacZα gap-filling assay, except that the gap filled by the polymerase is in a plasmid construct. After filling, the plasmid is directly transfected into bacteria, and bacterial colonies rather than phage plaques are scored by blue-white screening (39). Like most phage-based assays, the assay screens a large region (288 nt) of the lacZα gene, including the promoter sequence. Although this assay does not mimic all the steps of reverse transcription, it avoids the enzymatic (T3 RNA polymerase and Pfu polymerase) background issues of the PCR-based assay. The results (Table 2) were in strong agreement with those of the PCR-based assay (Table 1). Fidelity was lowest with 6 mM (5.6 mM free) Mg2+, improved about 2-fold between 1.98 and 0.6 mM free Mg2+, and improved dramatically (∼7-fold) under more physiological conditions (0.24 mM free Mg2+/5 μM dNTPs). Once again, results from the plasmid based lacZα complementation assay are in agreement with those of the PCR-based assay, and the fidelity of RT is considerably high at physiological Mg2+ concentrations.

TABLE 2.

Colony mutation frequencies for various Mg2+ and dNTP concentrations in plasmid-based lacZα complementation assay

| Total Mg2+ (free Mg2+) (mM)a | Total dNTPs (μM) | No. of white and faint blue colonies | Total no. of colonies | CMF (×10−3) | CMF − Bkg (×10−3)c | Relative fidelityd | P valuee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| —b | —b | 17 | 10,138 | 1.7 | |||

| 6 (5.6) | 100 | 71 | 4,328 | 16 | 14 | 1 | |

| 2 (1.98) | 5 | 27 | 2,866 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 1.9 | 0.0066 |

| 2 (1.6) | 100 | 117 | 12,602 | 9.3 | 7.6 | 1.9 | <0.0001 |

| 1.5 (1.1) | 100 | 51 | 5,983 | 8.5 | 6.8 | 2.1 | <0.0001 |

| 1 (0.6) | 100 | 54 | 6,492 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 2.1 | <0.0001 |

| 0.25 (0.24) | 5 | 19 | 5,195 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 7.0 | <0.0001 |

Free Mg2+ was calculated as described in Materials and Methods using the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and ATP.

—, background was determined by transfecting plasmids with unfilled gaps into bacteria. CMF was defined as white and faint blue colonies divided by total colonies. Refer to Results and Materials and Methods for details.

CMF − Bkg, frequency minus the background frequency from the first row (see footnote b).

All values are relative to the 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP CMF − Bkg value (0.014). The 0.014 value was divided by the CMF − Bkg value for each condition to determine relative fidelity. Higher numbers indicate greater fidelity.

Values were calculated using a chi-square analysis after performing the background correction by subtracting (0.0017 × total colonies) from the white and faint blue colonies for each condition. All values were scored against that for the 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP condition.

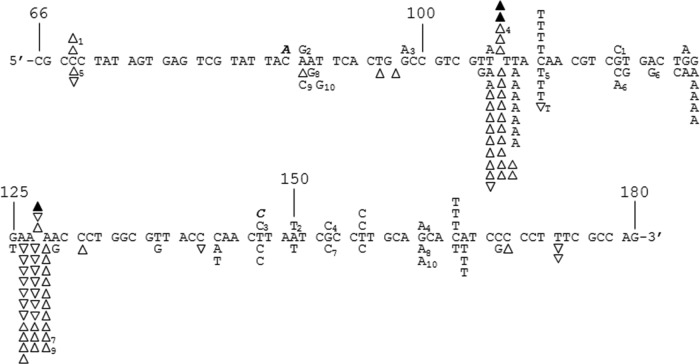

Estimation of mutation frequency from CMF and sequencing data.

For the PCR-based assay, an estimate of the base misincorporation frequency can be made from the CMFs in Table 1 and the sequencing results in Fig. 2. Calculations depend on the proportion of errors that were deletions or insertions (indels) versus substitutions, and whether a particular substitution error produces a white or faint blue phenotype. Indels result in frameshift mutations that are always detected as white or faint blue colonies. In contrast, less than half of the substitutions made in the assay result in a mutant phenotype (19). Sequencing of mutant colonies from experimental controls showed that 19/24 (∼79%) had deletion mutations near the PvuII site (see Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods), probably resulting from inaccurate cleavage or ligation errors. Since the Pfu PCR step is the only polymerase step in the controls, if mutations made during plasmid amplification in the bacteria are ignored, then only 5/24 errors (21%) in the controls resulted from Pfu during PCR. This translates to a Pfu-derived CMF of ∼0.0021 (the average CMF value for the control assays in Table 1) × 0.21, or 0.0004, which is one Pfu-derived error per 2,500 colonies (note that this estimation is a rough approximate, as it is based on only 5 recovered mutations). This is consistent with a mutation rate for Pfu in the ∼1× 10−6 to 2 × 10−6 range reported by others (see example calculation below) (47). The fact that background mutations were mostly ligation errors outside the region scored for mutations made it relatively easy to distinguish mutations resulting from HIV RT (or T3 RNA polymerase [see Discussion]) in the experimental sequences. Excluding these background mutations, in experiments with 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTPs, ∼28% (7/25) of recovered mutations were indels and ∼72% (18/25) substitutions. This was similar to proportions determined in this laboratory under comparable conditions (38), although there has been significant variation depending on the particular investigators and version of the lacZα complementation assay used (22, 25, 26, 28, 48–50). The assay used in this study included 230 nt (115 from each round of RT synthesis) of the lacZα gene (Fig. 1). Based on the proportion of substitutions to indels from Fig. 2, the average CMF of 0.0083 from Table 1, and using a 33.6% detection rate for substitutions in this region (Fig. 1C), the mutation frequency for the 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP condition would be 8.3 × 10−5, or ∼1 error per 12,000 incorporations {(0.0083 × 0.35)/230 = 1.3 × 10−5 for indels, and [(0.0083 × 0.65)/230]/0.336 = 7.0 × 10−5 for substitutions; total is 8.3 × 10−5 for both (see footnotes for further details)}. For the more physiological condition of 0.25 mM Mg2+/5 μM dNTPs, the average CMF from Table 1 was 0.0017. Results showed a greater proportion of indels, ∼59% (63/106), with ∼41% substitutions (43/106). The same approach yields a mutation frequency of 1.3 × 10−5, or ∼1 error per 77,000 incorporations. This number suggests a fidelity for RT in vitro that is similar to replication in cells (30–33). Note that the stated proportions of indels versus substitutions underrepresents RT's propensity for making substitutions, as only about 1/3 (see above) of the possible substitutions are detectable. Also note that the calculations for error frequency would include error contributions from T3 RNA polymerase (see above), so the actual mutation frequency for HIV RT may be somewhat lower (see Discussion).

FIG 2.

DNA sequence analysis from the PCR-based lacZα complementation fidelity assay. The 115-base region analyzed for mutations is shown (see Fig. 1). The coding strand for lacZα is shown in the 5′-3′ direction (bottom strand in Fig. 1C). Numbering is as shown in Fig. 1C. Deletions are shown as regular triangles, insertions are shown as downward triangles with the inserted base shown adjacent to the downward triangle, unless it was same as the base in a nucleotide run, and base substitutions are shown directly above or below the sequence. Substitutions shown correspond to the recovered sequence for the coding strand; however, these mutations could have occurred during synthesis of the noncoding strand as well (i.e., a C-to-A change shown here could have resulted from a C-to-A change during synthesis of the coding strand or a G-to-T change during synthesis of the noncoding strand) (see Fig. 1 and Results). Mutations recovered from HIV RT at 6 mM Mg2+ and 100 μM dNTPs and mutations from background controls are shown above the sequence as open triangles and normal text or filled triangles and bold italicized text, respectively. Mutations from HIV RT at 0.25 mM Mg2+ and 5 μM dNTPs are shown below the sequence. Individual sequence clones which had multiple mutations (more than one mutation event) are marked with subscripts adjacent to the mutations. Several clones with deletions (either single or multiple deletions) at positions 181 to 183, just outside the scored region, were also recovered (data not shown). This was the dominant mutation type recovered in background controls (19 out of 24 total sequences) and probably resulted from improper ligation events or damaged plasmid vectors (see Results). Two out of 22 HIV RT-derived sequences at 6 mM Mg2+ and 62 out of 162 HIV RT-derived sequences at 0.25 mM Mg2+ also had these deletions.

(Some mutations [4 under the 6 mM condition and 6 under the 0.25 mM condition] were recovered as part of compound mutations as indicated in Fig. 2. For calculation purposes, these were counted as a single substitution if they were recovered with another substitution and were counted only in the indel category if they were recovered with a deletion or insertion. Using this approach, for calculation purposes with 6 mM Mg2+ and 100 μM dNTPs, 7/20 [35%] and 13/20 [65%] of the mutations were indels or substitutions, respectively. For 0.25 mM Mg2+ and 5 μM dNTPs, the numbers were 63/106 [59%] and 43/106 [41%], respectively.)

It is also possible to estimate the mutation frequency using the plasmid-based assay results (Table 2). As no sequencing data were acquired, it is only possible to obtain a combined error rate for both substitutions and indels. These calculations yield mutation rates of 7.1 × 10−5 for 6 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTPs and 1.0 × 10−5 for 0.25 mM Mg2+/5 μM dNTPs (see reference 39 for calculation details). These figures are in strong agreement with those calculated from the PCR-based assay.

Analysis of fidelity by steady-state kinetics also demonstrates higher fidelity with low Mg2+.

Kinetic assays have been used by many groups as a reliable way to estimate polymerase fidelity (reviewed in references 20, 51, and 52). A major strength of this approach is the ability to analyze individual types of misincorporations and also the extension of primers with mismatches at the 3′ end. One drawback is that these assays are typically performed with just a small set of sequences, so the effect of sequence context on fidelity is limited (53). In addition, high nonphysiological concentrations of some nucleotides are required to force measurable misincorporation or mismatch extension in the time scale of the assay. Therefore, the assays are nonphysiological with respect to dNTP concentrations; however, physiological levels of Mg2+ can be evaluated. We performed both mismatched primer extension and running-start assays using the constructs shown in Fig. 3, which we have used previously in fidelity assays (41). The running-start assays test RT's ability to misincorporate at a template C or G residue (depending on construct) after a “running-start” on a run of T's immediately downstream of the primer 3′ terminus. Assays whose results are shown in Table 3 evaluated these reactions at different concentrations of free Mg2+. Since large amounts of nucleotides are often added to these types of reactions to force misincorporation, concentrations of total Mg2+ were altered as described in Materials and Methods to obtain the desired free Mg2+ concentration. Misincorporation ratios and relative fidelity (compared to the 6 mM free Mg2+ condition, which showed the lowest fidelity) were determined by comparing the rate of misincorporation of an A nucleotide to the rate of adding the correct G nucleotide opposite a C in the template. Experiments were analyzed on denaturing PAGE gels (Fig. 4A). Similar to what was observed in the lacZα complementation assays, fidelity increased modestly between 6 and 0.5 mM Mg2+, reaching almost 3-fold greater by 0.5 mM. Statistical analysis indicated that fidelity values for 2 and 1 mM Mg2+ were not statistically different from that under the 6 mM Mg2+ condition. A large increase, to ∼7-fold-greater fidelity, was observed at 0.25 mM Mg2+. In a second running-start analysis, different mismatches opposite a C or G in the template strand were measured at 2 mM and 0.25 mM free Mg2+ (Table 4). A pronounced increase in fidelity was observed at the lower concentration for all mismatches, with the exception of G·A. Two mismatch types (C·T and C·C) showed a 2-fold increase in fidelity (note that “relative fidelity” in this table is relative to that in the 2 mM Mg2+ reactions rather than 6 mM as in Table 3), while two others (C·A and G·T) showed ∼6-fold-greater fidelity with lower Mg2+. In general, fidelity differences were greater for mismatches that tend to be easier for polymerases to make (e.g., C·A and G·T) and lesser for those that are more difficult to make (e.g., C·T, C·C, and G·A).

TABLE 3.

Running-start misincorporation assay with various Mg2+ concentrations

| Base paira | [Mg2+] (mM)b | Vmax, relc | Km (μM)d | Vmax/Km (μM−1)e | Misinsertion ratiof | Relative fidelityg | P valueh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C·G | 6 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 0.68 ± 0.33 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 0.82 ± 0.43 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 1 | |||

| 0.5 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 0.72 ± 0.27 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 1 | |||

| 0.25 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 0.32 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 1 | |||

| C·A | 6 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 282 ± 24 | (1.7 ± 0.5) × 10−3 | (1.8 ± 0.5) × 10−4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 825 ± 217 | (6.1 ± 1.1) × 10−4 | (1.5 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 1.2 | 0.50 | |

| 1 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 1,025 ± 189 | (4.0 ± 0. 5) × 10−4 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 10−4 | 1.6 | 0.13 | |

| 0.5 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 1,841 ± 143 | (2.5 ± 0.2) × 10−4 | (7.8 ± 0.7) × 10−5 | 2.3 | 0.061 | |

| 0.25 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 4,574 ± 1,221 | (6.8 ± 2.9) × 10−5 | (2.5 ± 0.8) × 10−5 | 7.2 | 0.00079 |

Refer to the running-start constructs in Fig. 3. In this assay, incorporation of a correct G residue at a template C was compared to incorporation of an incorrect A residue at this same position. All assay included saturating concentrations of dATP to produce a “running-start” over the 4 template T nucleotides that preceded the C.

The concentration of free Mg2+ in the reactions is shown. Free Mg2+ was calculated as described in Materials and Methods using the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and ATP.

Vmax, rel = Ii − Ii − 1, where Ii is the sum of band intensities at the target site and beyond and Ii − 1 is the intensity of the band prior to the target band. See Materials and Methods for a description. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Km of the nucleotide being incorporated at the target site (dGTP for C·G and dATP for C·A). Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Ratio of [Vmax/Km (mismatch)]/[Vmax/Km (match)] at each respective Mg2+ concentration. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are relative to that at 6 mM Mg2+. Determinations were made by dividing the misinsertion ratio at 6 mM by the ratios at the other Mg2+ concentrations. Higher values indicate greater fidelity.

Values were calculated using a standard Student t test. All values were scored against that at 6 mM Mg2+.

FIG 4.

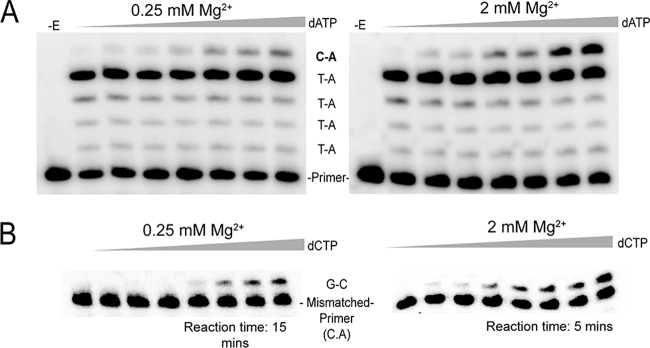

Representative experiments for running-start and mismatch extension assays. (A) Running-start misincorporation of C·A base pair at 0.25 and 2 mM Mg2+. Reactions were performed on the primer-template shown in Fig. 3 for 3 min with a final free Mg2+ concentration of 0.25 or 2 mM (adjusted according to the total concentration of dNTPs in each reaction using the KD values of Mg2+ and ATP). A fixed concentration of dATP (55 μM) was used in all running-start reactions for elongation of the primer to the target site. The concentration of the target nucleotide (dATP for C·A insertion) in each lane was, from left to right, 0, 400, 630, 1,380, 2,610, and 3,660 μM. For other base pair misinsertions noted in Table 4, the target nucleotide was changed according to the desired misinsertion. −E, no enzyme was added. (B) Extension of a mismatched primer-template with a C·A 3′ terminus, using 0.25 and 2 mM Mg2+. Reactions were performed on the primer-template shown in Fig. 3 for the indicated time with a final free Mg2+ concentration of 0.25 or 2 mM (adjusted as described above). The concentration of the next correct nucleotide (dCTP) in each lane was, from left to right, 0, 50, 100, 200, 400, 630, 1,200 and 1,870 μM. All mismatched primer-templates were extended for 5 min at 2 mM Mg2+, whereas in 0.25 mM Mg2+, primer-template constructs with 3′ termini of C·C and G·A were extended for 20 min and all other mismatched primer-templates were extended for 15 min.

TABLE 4.

Running-start misincorporation assay of various mismatches at 0.25 mM or 2 mM Mg2+

| Base paira | [Mg2+] (mM)b | Vmax, relc | Km (μM)d | Vmax/Km (μM−1)e | Misinsertion ratiof | Relative fidelityg | P valueh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C·G | 2 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 0.68 ± 0.33 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 1 | ||

| 0.25 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 0.32 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 1 | |||

| G·C | 2 | 1.4 ± 0.26 | 1.2 ± 0.64 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1 | ||

| 0.25 | 3.0 ± 0.96 | 3.4 ± 1.66 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1 | |||

| C·T | 2 | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 1,863 ± 670 | (2.9 ± 0.33) × 10−4 | (6.7 ± 2.6) × 10−5 | 1 | 0.014 |

| 0.25 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 2,004 ± 582 | (8.9 ± 3.8) × 10−5 | (3.3 ± 0.8) × 10−5 | 2.0 | ||

| C·A | 2 | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 825 ± 217 | (6.1 ± 1.1) × 10−4 | (1.5 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 1 | 4.7 × 10−5 |

| 0.25 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 4,574 ± 1,221 | (6.8 ± 2.9) × 10−5 | (2.5 ± 0.8) × 10−5 | 6 | ||

| C·C | 2 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 312 ± 166 | (2.9 ± 0.8) × 10−4 | (6.7 ± 1.9) × 10−5 | 1 | 0.040 |

| 0.25 | 0.24 ± 0.11 | 2,666 ± 478 | (9.0 ± 2.8) × 10−5 | (3.3 ± 0.9) × 10−5 | 2.0 | ||

| G·T | 2 | 0.36 ± 0.16 | 242 ± 50 | (1.5 ± 0.9) × 10−3 | (1.3 ± 0.8) × 10−3 | 1 | 0.065 |

| 0.25 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 1,488 ± 628 | (1.9 ± 0.7) × 10−4 | (2.1 ± 0.8) × 10−4 | 6.2 | ||

| G·A | 2 | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 1,515 ± 85 | (2.5 ± 0.6) × 10−4 | (2.1 ± 0.5) × 10−4 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 0.25 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 427 ± 23 | (3.3 ± 2.5) × 10−4 | (3.7 ± 1.5) × 10−4 | 0.6 |

Refer to the running-start constructs in Fig. 3. The particular mismatch that was measured after incorporation of a run of A's over a run of T's on the template is shown in the column.

The concentration of free Mg2+ in the reactions is shown. Free Mg2+ was calculated as described in Materials and Methods using the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and ATP.

Vmax, rel = Ii − Ii − 1, where Ii is the sum of band intensities at the target site and beyond and Ii − 1 is the intensity of the band prior to the target band. See Materials and Methods for a description. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Km of the nucleotide being incorporated at the target site (dGTP for C·G and dATP for C·A). Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Ratio of [Vmax/Km (mismatch)]/[Vmax/Km (match)] at each respective Mg2+ concentration. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Relative fidelity values are relative to that at 2 mM for each mismatch type. Determinations were made by dividing the misinsertion ratio at 2 mM by the ratio at 0.25 mM. Higher values indicate greater fidelity. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values were calculated using a standard Student t test. Misinsertion ratio values from experiments at 0.25 mM Mg2+ were compared against that at the 2 mM Mg2+ condition listed above for each mismatch type.

A second set of assays was used to examine the ability of RT to extend primers with mismatched 3′ termini (Fig. 4B). Table 5 shows results from extension reactions with a C·A mismatch at various Mg2+ concentrations. The results were similar to the running-start results with the C·A misincorporation (Table 3). Extension of the mismatch was more difficult as the concentration of Mg2+ decreased, but there was not a significant difference in comparison to the 6 mM Mg2+ result until the Mg2+ was lowered to 0.5 mM (as indicated by P values).

TABLE 5.

Extension of C·A mismatched primer-template with various Mg2+ concentrations

| Base pair at the 3′ enda | [Mg2+] (mM)b | Vmax (%/min)c | Km (μM)d | Vmax/Kme | Standard extension efficiencyf | Relative fidelityg | P valueh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C·G | 6 | 36.4 ± 7.7 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 59.7 ± 12.7 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 21.4 ± 2.0 | 0.37 ± 0.13 | 57.8 ± 19.2 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 23.8 ± 3.6 | 0.44 ± 0. 08 | 54.1 ± 5.0 | 1 | |||

| 0.5 | 23.2 ± 3.1 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 55.2 ± 2.8 | 1 | |||

| 0.25 | 24.1 ± 10.8 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 58.8 ± 28.1 | 1 | |||

| C·A | 6 | 9.6 ± 3.6 | 204 ± 122 | (4.7 ± 0.14) × 10−2 | (7.8 ± 0.15) × 10−4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 11.1 ± 2.9 | 445 ± 188 | (2.5 ± 0. 57) × 10−2 | (4.3 ± 0.94) × 10−4 | 1.8 | 0.10 | |

| 1 | 11.2 ± 4.0 | 507 ± 194 | (2.2 ± 0.57) × 10−2 | (4.0 ± 0.10) × 10−4 | 2.0 | 0.11 | |

| 0.5 | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 311 ± 153 | (1.4 ± 0.3) × 10−2 | (2.5 ± 0.71) × 10−4 | 3.1 | 0.055 | |

| 0.25 | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 1,546 ± 714 | (2.8 ± 1.9) × 10−3 | (4.8 ± 3.4) × 10−5 | 16.3 | 0.0067 |

Refer to the mismatch extension constructs in Fig. 3. In this assay, primers with a matched C·G or a mismatched C·A at the 3′ end were extended.

The concentration of free Mg2+ in the reactions is shown. Free Mg2+ was calculated as described in Materials and Methods using the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and ATP.

Vmax is the maximum velocity of extending each primer-template construct. See Materials and Methods for a description. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Km of the next correct nucleotide being added (dCTP for C·G and C·A extension). Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

[Vmax/Km (mismatch)]/[Vmax/Km (match)] at each respective Mg2+ concentration. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are relative to the 6 mM condition. Determinations were made by dividing the standard extension efficiency at 6 mM Mg2+ by this same value at other Mg2+ concentrations. Higher values indicate greater fidelity.

Values were calculated using a standard Student t test. All values were scored against that at 6 mM Mg2+.

Extension of several mismatch types was examined at 0.25 mM and 2 mM Mg2+. Once again, extension was more difficult with lower Mg2+ concentrations, and the magnitude of the difference was dependent on the particular mismatch (Table 6). Small but insignificant differences were observed for G.·A and G·T, while C·C, C·T, and C·A mismatches showed more significant differences. In this regard, the mismatch extension assays differed from the misincorporation assays in that there was not a clear trend for Mg2+ showing a greater effect with mismatches that are easier to make.

TABLE 6.

Mismatched primer extension at 0.25 or 2 mM Mg2+

| Base pair at the 3′ enda | [Mg2+] (mM)b | Vmax (%/min)c | Km (μM)d | Vmax/Kme | Standard extension efficiencyf | Relative fidelityg | P valueh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C·G | 2 | 21.4 ± 2.0 | 0.37 ± 0.13 | 57.8 ± 19.2 | 1 | ||

| 0.25 | 24.1 ± 10.8 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 58.8 ± 28.1 | 1 | |||

| G·C | 2 | 39.9 ± 14.5 | 0.27 ± 0.13 | 147.8 ± 40.6 | 1 | ||

| 0.25 | 18.7 ± 3.7 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 133.6 ± 14.3 | 1 | |||

| C·T | 2 | 21.2 ± 2.7 | 500 ± 181 | (4.2 ± 1.8) × 10−2 | (7.3 ± 3.3) × 10−4 | 1 | 0.013 |

| 0.25 | 3.1 ± 0.42 | 748 ± 57 | (4.1 ± 0. 59) × 10−3 | (7.1 ± 1.0) × 10−5 | 10 | ||

| C·A | 2 | 11.1 ± 2.9 | 445 ± 188 | (2.5 ± 0. 57) × 10−2 | (4.3 ± 0.94) × 10−4 | 1 | 5.2 × 10−5 |

| 0.25 | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 1,546 ± 714 | (2.8 ± 1.9) × 10−3 | (4.8 ± 3.4) × 10−5 | 8.9 | ||

| C·C | 2 | 0.70 ± 0.29 | 77 ± 14 | (9.1 ± 2.2) × 10−3 | (1.6 ± 0.38) × 10−4 | 1 | 0.027 |

| 0.25 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 61 ± 34 | (3.3 ± 2.1) × 10−3 | (5.6 ± 3.6) × 10−5 | 2.9 | ||

| G·T | 2 | 18.6 ± 3.3 | 157 ± 44 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | (8.1 ± 2.5) ×10−4 | 1 | 0.13 |

| 0.25 | 8.6 ± 1.5 | 120 ± 6 | (7.2 ± 1.4) × 10−2 | (5.4 ± 1.1) × 10−4 | 1.5 | ||

| G·A | 2 | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 196 ± 50 | (4.8 ± 1.6) × 10−3 | (3.2 ± 1.0) × 10−5 | 1 | 0.23 |

| 0.25 | 0.50 ± 0.30 | 169 ± 13 | (2.9 ± 1.6) × 10−3 | (2.2 ± 1.3) × 10−5 | 1.5 |

Refer to the mismatch extension constructs in Fig. 3. In this assay, primers with a matched C·G or a mismatched C·T, C·A, or C·C at the 3′ end were extended on one construct. A second construct with a matched G·C or mismatched G·T or G·A was also used.

The concn of free Mg2+ in the reactions is shown. Free Mg2+ was calculated as described in Materials and Methods using the dissociation constant for Mg2+ and ATP.

Vmax is the maximum velocity of extending each primer-template construct. See Materials and Methods for a description. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Km of the next correct nucleotide being added (dCTP for C·G, C·T, C·A, and C·C or dGTP for G·C, G·T, and G·A extensions). Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

[Vmax/Km (mismatch)]/[Vmax/Km (match)] at each respective Mg2+ concentration. Values are averages from at least 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Values are relative to that at 2 mM. Determinations were made by dividing the standard extension efficiency at 2 mM Mg2+ by the extension efficiency at 0.25 mM Mg2+. Higher values indicate greater fidelity.

Values were calculated using a standard Student's t test. Misinsertion ratio values from experiments at 0.25 mM Mg2+ were compared against that under the 2 mM Mg2+ condition listed above for each mismatch type.

Overall, results from running-start and mismatch extension assays are in strong agreement with the lacZα complementation assays in showing that fidelity improves at lower Mg2+ concentrations and is much higher at the proposed physiological levels in lymphocytes (13, 16). Both misincorporation (as determined by running-start assays) and mismatch extension (as determined with mismatched primer-templates) are influenced, suggesting that both steps involved in fidelity are affected by Mg2+ concentrations.

DISCUSSION

The results demonstrate that the fidelity of HIV RT can be dramatically changed over just a small range of Mg2+ concentrations. Using concentrations optimized for RT catalysis (2 to 6 mM) resulted in about a 5- to 7-fold-lower fidelity than with concentrations closely mimicking free Mg2+ in lymphocytes (∼0.25 mM) (Tables 1 and 2). Fidelity assays, including both steady-state and lacZα complementation assays, showed only modestly lower fidelity at 6 mM versus 2 mM or even 0.5 mM (in steady-state assays) Mg2+ (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 5). In contrast, a dramatic increase in fidelity was observed at 0.25 mM Mg2+. This may mean that HIV RT fidelity is only modestly sensitive to Mg2+ concentrations above 0.5 mM Mg2+.

Significant changes in fidelity in response to Mg2+ concentrations have also been demonstrated for Taq polymerase (54). Results showed that fidelity was highest when the concentrations of total dNTPs and Mg2+ were equal. When Mg2+ was present in excess, fidelity decreased by an order of magnitude or more for some mutation types. Like for HIV RT (Tables 3 to 6), the enhanced fidelity with Taq resulted from both a lowered misincorporation rate and a lowered ability to extend mismatched primer-templates. Importantly, the higher fidelity for Taq observed under these conditions also resulted in a reduced rate of synthesis (54). This is why PCRs are typically performed with Mg2+ in excess over dNTPs. Interestingly, both Vent and Pfu, thermostable polymerases with proofreading activity, showed reduced fidelity with low Mg2+ concentrations (47). Therefore, higher fidelity with lower Mg2+ does not appear to be a general property of all polymerases. This was also the case with MuLV RT, for which fidelity was unaffected at high versus low Mg2+ (Table 1). In addition to Mg2+, other experiments have shown that nonphysiological acidic pHs (∼5 to 6.5) can improve the fidelity for several polymerases, including HIV RT (55, 56). For HIV RT, enhanced fidelity at a lower pH seemed to result mostly from an inability to extend mismatched primer-templates rather than a lower rate of misincorporation. Our experiments were conducted at pH 7.7, which is slightly higher than normal physiological cytosolic pH (∼7.2). However, we also tested the 2 mM Mg2+/100 μM dNTP and 0.25 mM Mg2+/5 μM dNTP conditions at pH 7.1 and found that the pH did not significantly alter fidelity (data not shown). These experiments suggest that RT fidelity is not particularly sensitive to pH within this limited near-physiological range.

The reason why lower Mg2+ concentrations increase HIV RT (or Taq) fidelity remains to be determined. Reverse transcriptase has at least 3 or 4 binding sites for divalent cations, 2 in the polymerase active site and 1 or 2 in the RNase H active site (see the introduction). It is possible that more sites exist. For example, E. coli polymerase I may have as many as 21 divalent cation binding sites, and the roles, if any, for those sites not involved in catalysis are unknown (57). Analysis of retrotransposon RTs suggests that the two binding sites in the polymerase active-site domain have vastly different affinities for Mn2+ and Mg2+, and occupation of one versus two sites and interactions between the sites can significantly alter RT enzymatic properties (58, 59). Nucleic acid binding titrations of HIV RT also suggest two or more binding states that are dependent on the concentration of Mg2+ (60). The results presented here are, at least in principle, consistent with RT binding sites that have broadly different affinities for Mg2+ controlling fidelity. All the assays (Tables 1 to 6) showed a modest effect on fidelity between ∼1 and 6 mM Mg2+ and a much more significant change at low Mg2+ concentrations. This suggests that a high-affinity binding site which is fully occupied at the lower Mg2+ levels may enhance fidelity upon titration. Interplay between this site and a lower-affinity site(s) may also affect fidelity, as was proposed for altering other properties for retrotransposon RTs (58, 59). It is also conceivable that divalent cation binding in the RNase H site could influence fidelity, as active-site mutations in this domain that eliminate RNase H activity can affect fidelity (61). Finally, the progressive reduction in enzyme efficiency (as represented by Vmax/Km values in Table 3) as the Mg2+ concentration is gradually reduced suggests that the increased fidelity may be a function of the lower velocity of the reaction, which increases the residence time on each template base and therefore affords better discrimination. We are pursuing further experiments with the hope of uncovering further mechanistic details for these observations.

Sequencing results indicated that the proportion of indels versus substitutions increased under the 0.25 mM versus 6 mM Mg2+ conditions (Fig. 2 and Results). A significant decrease in substitutions would be predicted based on the running-start assay results (Tables 3 and 4), so it is possible that low Mg2+ concentrations increase fidelity mainly by lowering substitutions rather than altering indel rates. The spectrum of mutations obtained at low Mg2+ concentrations showed both differences and similarities from what has been observed in cells over a similar region of the lacZα gene. In the cellular experiments, the ratio of substitutions to indels was skewed toward the former, with a high proportion of G-to-A mutations (30–32). This mutation type and changes of T to A were the most common substitutions observed in the current work, with each comprising 9 of 43 total substitutions. However, the frequency of G-to-A mutations is still significantly greater in the cellular assays than in our assays (see below). The two main hot spots for indels in our assays with low Mg2+ (Fig. 2) also matched indel hot spots observed in cellular assays from other groups (31, 32, 62). There are also differences even between cellular experiments, with one group calculating a much lower rate for the proportion of frameshifts to total recovered mutations than was determined by others (∼5% versus >25%) (30, 31). A recent study found that although the HIV mutation rates for different cell types were near constant, the spectra of mutations observed were significantly different (63). This suggests that there may be several factors determining the reverse transcription mutation spectrum, including cell type, RT subtype, and the particular assay system used to score mutations. A future goal is to obtain a much larger mutational spectrum data set in vitro that will allow a more comprehensive comparison between mutations made by RT in vitro and those made during reverse transcription and replication in cells.

Comparing cellular and in vitro mutation spectra is complicated by several factors. In the in vitro assays performed in this study or in other studies using an RNA template, T3 or a comparable RNA polymerase is used to make the RNA template. Like for the RNA polymerase II enzyme in cells that synthesizes the HIV genome, the error spectrum of T3 and other phage polymerase is unknown. Contributions to the sequence profile from this enzyme are likely small under the 6 mM Mg2+ condition, for which the CMFs were far above the assay background (Table 1), but more significant with 0.25 mM Mg2+. Pfu polymerase, used in the PCR step, has very high fidelity (mutation rate of ∼1 × 10−6 to 2 × 10−6 [47]), so its contribution under both Mg2+ conditions would be small, as was demonstrated (see Results). Although the mutation frequency of T3 and other RNA polymerases is not known, limited results suggest that it is unlikely to be higher than that of RT (25, 28). This, and the fact that two rounds of RT synthesis were performed in the PCR-based assay, suggests that most errors in our assays would have resulted from RT synthesis. Cellular profiles also include mutations resulting from cellular sources, most notably APOBEC3G and dUTP incorporation into DNA (64–67). These cellular processes would tend to increase substitutions (particularly G to A) during reverse transcription. Though they are countered by the viral Vif protein in the case of APOBEC3G, and Vpr protein in the case of dUTP incorporation, some read-through may occur, leading to an increase in cellular mutations (67). Recent reports also suggest that double-stranded RNA deaminase (ADAR1 and ADAR2) may influence cell-derived viral mutations (68–71). In addition to these promutagenic mechanisms, mistakes made during second-strand synthesis could be subjected to the cellular proofreading machinery (33). This would be expected to result in up to a 50% reduction in errors on this strand, and if the mutation rate during the synthesis of both strands is assumed to be nearly equal, a 25% reduction in the overall mutation rate of reverse transcription. Beyond Mg2+, it is also possible that other small cellular components influence RT. For example, polyamines, which are present at near millimolar levels in cells, have been reported to increase HIV RT fidelity (72). Finally, there is evidence that HIV NC can affect fidelity by promoting extension and correction of mismatches (73, 74). However, studies in our laboratory using an α complementation assay showed no difference in fidelity in the presence and absence of NC (38).

Interestingly, results suggest that suboptimal Mg2+ concentrations, though modestly decreasing RT's catalytic activity, actually improve DNA synthesis efficiency. Using an in vitro system with a DNA primer and RNA template to mimic the synthesis of strong-stop minus-strand DNA (−ssDNA), lower Mg2+ levels (∼0.1 mM) yielded significantly higher quantities of −ssDNA than reactions performed at higher concentrations (2 to 6 mM) (75). The authors suggest that stabilization of some template secondary structures by higher Mg2+ leads to more RT pausing. The paused complexes are susceptible to more extensive RNase H cleavage that can destabilize the nascent DNA-RNA template interaction, leading to dissociated “dead-end” DNA synthesis products and “stalled” RT complexes. We conducted similar experiments on the RNA template used for the PCR-based fidelity assay. At physiological dNTP concentrations (5 μM), reactions were modestly more efficient at lower Mg2+ concentrations, showing a decrease in some pause sites and an increase in fully extended products (Fig. 5).

Results presented here indicate that the low free Mg2+ levels in lymphocytes lead to an increase in HIV RT fidelity, perhaps severalfold. This brings the fidelity determined in vitro in line with that observed in cell culture, both having mutation rates in the ∼1 × 10−5to 3 × 10−5 range (30–32). It also brings HIV RT fidelity in vitro in the range of the in vitro fidelity of other RTs (20). Interestingly, although the fidelity of several RTs (e.g., AMV and MuLV RTs) is reported to be greater than that of HIV RT in vitro, cell culture analysis suggests similar fidelities for the viruses (33). The cellular results are much more consistent with the findings in this study that show MuLV and HIV RTs have similar fidelities under more physiological conditions (Table 1). Although it is not clear why HIV RT fidelity is sensitive to Mg2+ levels while MuLV RT is not, HIV RT has a much lower Km for dNTPs than MuLV RT, a property that allows HIV to replicate in macrophages, in which the concentration of dNTPs is extremely low (17). As dNTPs bind in conjunction with Mg2+, this suggests that one or more of the cation binding sites on these enzymes have significantly different properties.

Finally, it could be argued that the concentration of free Mg2+ in lymphocytes may fluctuate (e.g., during the cell cycle as nucleotide pools change), and the 0.25 mM level quoted here is based on limited data. Therefore, the level could be higher or even lower, and more work would be required to unequivocally determine the free Mg2+ concentration in lymphocytes under different conditions. Although this is true, results presented here for fidelity, and from others for RNA-directed DNA synthesis (75), show that in vitro conditions using low Mg2+ concentrations yield results that are more consistent with those determined or predicted in cells. This consistency represents a strong argument for those conditions more closely matching cellular conditions, at least for replication in rapidly dividing culture cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medicine grant number GM051140 to J.J.D. and by the UK BBSRC (project grant BB/F00687X/1); B.J.K. was a UK BBSRC-supported Ph.D. student.

We thank Michael Parniak of the University of Pittsburg for the HIV RT clone and Katherine Fenstermacher for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts EJ, Hazuda DJ. 2012. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy, p 321–343 In Bushman FD, Nabel GJ, Swanstrom R. (ed), HIV from biology to prevention and treatment. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telesnitsky A, Goff SP. 1993. Reverse transcriptase. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan JA, Ohyama T, Howard K, Rausch JW, Cowan SM, Le Grice SF. 2000. Metal-ion stoichiometry of the HIV-1 RT ribonuclease H domain: evidence for two mutually exclusive sites leads to new mechanistic insights on metal-mediated hydrolysis in nucleic acid biochemistry. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 5:67–74. 10.1007/s007750050009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson KA. 2010. The kinetic and chemical mechanism of high-fidelity DNA polymerases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804:1041–1048. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joyce CM, Steitz TA. 1994. Function and structure relationships in DNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:777–822. 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura H, Katayanagi K, Morikawa K, Ikehara M. 1991. Structural models of ribonuclease H domains in reverse transcriptases from retroviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:1817–1823. 10.1093/nar/19.8.1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz SJ, Champoux JJ. 2008. RNase H activity: structure, specificity, and function in reverse transcription. Virus Res. 134:86–103. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W, Steitz TA. 1995. Recombining the structures of HIV integrase, RuvC and RNase H. Structure 3:131–134. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00142-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oda Y, Nakamura H, Kanaya S, Ikehara M. 1991. Binding of metal ions to E. coli RNase HI observed by 1H-15N heteronuclear 2D NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 1:247–255. 10.1007/BF01875518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire ME, Cowan JA. 2002. Magnesium chemistry and biochemistry. Biometals 15:203–210. 10.1023/A:1016058229972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moomaw AS, Maguire ME. 2008. The unique nature of Mg2+ channels. Physiology (Bethesda) 23:275–285. 10.1152/physiol.00019.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traut TW. 1994. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140:1–22. 10.1007/BF00928361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delva P, Pastori C, Degan M, Montesi G, Lechi A. 2004. Catecholamine-induced regulation in vitro and ex vivo of intralymphocyte ionized magnesium. J. Membr. Biol. 199:163–171. 10.1007/s00232-004-0686-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, McDonnell EH, Sedor FA, Toffaletti JG. 2002. pH effects on measurements of ionized calcium and ionized magnesium in blood. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 126:947–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gee JB, II, Corbett RJ, Perlman JM, Laptook AR. 2001. Hypermagnesemia does not increase brain intracellular magnesium in newborn swine. Pediatr. Neurol. 25:304–308. 10.1016/S0887-8994(01)00317-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delva P, Pastori C, Degan M, Montesi G, Lechi A. 1998. Intralymphocyte free magnesium and plasma triglycerides. Life Sci. 62:2231–2240. 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00201-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond TL, Roshal M, Jamburuthugoda VK, Reynolds HM, Merriam AR, Lee KY, Balakrishnan M, Bambara RA, Planelles V, Dewhurst S, Kim B. 2004. Macrophage tropism of HIV-1 depends on efficient cellular dNTP utilization by reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:51545–51553. 10.1074/jbc.M408573200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao WY, Cara A, Gallo RC, Lori F. 1993. Low levels of deoxynucleotides in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a strategy to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:8925–8928. 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyer JC, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. 1996. Analyzing the fidelity of reverse transcription and transcription. Methods Enzymol. 275:523–537. 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)75029-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menéndez-Arias L. 2009. Mutation rates and intrinsic fidelity of retroviral reverse transcriptases. Viruses 1:1137–1165. 10.3390/v1031137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston BD, Poiesz BJ, Loeb LA. 1988. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science 242:1168–1171. 10.1126/science.2460924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts JD, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. 1988. The accuracy of reverse transcriptase from HIV-1. Science 242:1171–1173. 10.1126/science.2460925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezende LF, Drosopoulos WC, Prasad VR. 1998. The influence of 3TC resistance mutation M184I on the fidelity and error specificity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:3066–3072. 10.1093/nar/26.12.3066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rezende LF, Kew Y, Prasad VR. 2001. The effect of increased processivity on overall fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biomed. Sci. 8:197–205. 10.1007/BF02256413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyer JC, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. 1992. Unequal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase error rates with RNA and DNA templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:6919–6923. 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyer PL, Hughes SH. 2000. Effects of amino acid substitutions at position 115 on the fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 74:6494–6500. 10.1128/JVI.74.14.6494-6500.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji J, Loeb LA. 1994. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase copying a hypervariable region of the HIV-1 env gene. Virology 199:323–330. 10.1006/viro.1994.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji JP, Loeb LA. 1992. Fidelity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase copying RNA in vitro. Biochemistry 31:954–958. 10.1021/bi00119a002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss KK, Chen R, Skasko M, Reynolds HM, Lee K, Bambara RA, Mansky LM, Kim B. 2004. A role for dNTP binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase in viral mutagenesis. Biochemistry 43:4490–4500. 10.1021/bi035258r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abram ME, Ferris AL, Shao W, Alvord WG, Hughes SH. 2010. Nature, position, and frequency of mutations made in a single cycle of HIV-1 replication. J. Virol. 84:9864–9878. 10.1128/JVI.00915-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansky LM, Temin HM. 1995. Lower in vivo mutation rate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 than that predicted from the fidelity of purified reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 69:5087–5094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansky LM. 1996. The mutation rate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is influenced by the vpr gene. Virology 222:391–400. 10.1006/viro.1996.0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu W-S, Hughes SH. 2012. HIV-1 reverse transcription, p 37–58 In Bushman FD, Nabel GJ, Swanstrom R. (ed), HIV from biology to prevention and treatment. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanjuán R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. 2010. Viral mutation rates. J. Virol. 84:9733–9748. 10.1128/JVI.00694-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou EW, Prasad R, Beard WA, Wilson SH. 2004. High-level expression and purification of untagged and histidine-tagged HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Protein Expr. Purif. 34:75–86. 10.1016/j.pep.2003.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeStefano JJ. 2010. Effect of reaction conditions and 3AB on the mutation rate of poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in a alpha-complementation assay. Virus Res. 147:53–59. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeStefano J, Ghosh J, Prasad B, Raja A. 1998. High fidelity of internal strand transfer catalyzed by human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:1483–1489. 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keith BJ, Jozwiakowski SK, Connolly BA. 2013. A plasmid-based lacZalpha gene assay for DNA polymerase fidelity measurement. Anal. Biochem. 433:153–161. 10.1016/j.ab.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendelman LV, Petruska J, Goodman MF. 1990. Base mispair extension kinetics. Comparison of DNA polymerase alpha and reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 265:2338–2346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liesch GR, DeStefano JJ. 2003. Analysis of mutations made during active synthesis or extension of mismatched substrates further define the mechanism of HIV-RT mutagenesis. Biochemistry 42:5925–5936. 10.1021/bi026998n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu H, Goodman MF. 1992. Comparison of HIV-1 and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase fidelity on RNA and DNA templates. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10888–10896 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenstermacher KJ, DeStefano JJ. 2011. Mechanism of HIV reverse transcriptase inhibition by zinc: formation of a highly stable enzyme-(primer-template) complex with profoundly diminished catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286:40433–40442. 10.1074/jbc.M111.289850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells VR, Plotch SJ, DeStefano JJ. 2001. Determination of the mutation rate of poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virus Res. 74:119–132. 10.1016/S0168-1702(00)00256-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curr K, Tripathi S, Lennerstrand J, Larder BA, Prasad VR. 2006. Influence of naturally occurring insertions in the fingers subdomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase on polymerase fidelity and mutation frequencies in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 87:419–428. 10.1099/vir.0.81458-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher TS, Prasad VR. 2002. Substitutions of Phe61 located in the vicinity of template 5′-overhang influence polymerase fidelity and nucleoside analog sensitivity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:22345–22352. 10.1074/jbc.M200282200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cline J, Braman JC, Hogrefe HH. 1996. PCR fidelity of Pfu DNA polymerase and other thermostable DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:3546–3551. 10.1093/nar/24.18.3546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bebenek K, Abbotts J, Roberts JD, Wilson SH, Kunkel TA. 1989. Specificity and mechanism of error prone replication by human immunodeficiency virus 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:16948–16956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji J, Hoffmann JS, Loeb L. 1994. Mutagenicity and pausing of HIV reverse transcriptase during HIV plus-strand DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:47–52. 10.1093/nar/22.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber J, Grosse F. 1989. Fidelity of human immunodeficiency virus type I reverse transcriptase in copying natural DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:1379–1393. 10.1093/nar/17.4.1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rezende LF, Prasad VR. 2004. Nucleoside-analog resistance mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and their influence on polymerase fidelity and viral mutation rates. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36:1716–1734. 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svarovskaia ES, Cheslock SR, Zhang WH, Hu WS, Pathak VK. 2003. Retroviral mutation rates and reverse transcriptase fidelity. Front. Biosci. 8:d117–d134. 10.2741/957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendelman LV, Boosalis MS, Petruska J, Goodman MF. 1989. Nearest neighbor influences on DNA polymerase insertion fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 264:14415–14423 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eckert KA, Kunkel TA. 1990. High fidelity DNA synthesis by the Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3739–3744. 10.1093/nar/18.13.3739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eckert KA, Kunkel TA. 1993. Fidelity of DNA synthesis catalyzed by human DNA polymerase alpha and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: effect of reaction pH. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:5212–5220. 10.1093/nar/21.22.5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]