ABSTRACT

On 30 March 2013, a novel avian influenza A H7N9 virus causing severe human respiratory infections was identified in China. Preliminary sequence analyses have shown that the virus is a reassortant of H7N9 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses. In this study, we conducted enhanced surveillance for H7N9 virus in Guangdong, China, from April to August 2013. We isolated two H7N9 viral strains from environmental samples associated with poultry markets and one from a clinical patient. Sequence analyses showed that the Guangdong H7N9 virus isolated from April to May shared high sequence similarity with other strains from eastern China. The A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus isolated from the Guangdong patient on 10 August 2013 was divergent from previously sequenced H7N9 viruses and more closely related to local circulating H9N2 viruses in the NS and NP genes. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that four internal genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus—the NS, NP, PB1, and PB2 genes—were in clusters different from those for H7N9 viruses identified previously in other provinces of China. The discovery presented here suggests that continuing reassortment led to the emergence of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus as a novel H7N9 virus in Guangdong, China, and that viral adaptation to avian and human hosts must be assessed.

IMPORTANCE In this study, we isolated and characterized the avian influenza A H7N9 virus in Guangdong, China, from April to August 2013. We show that the viruses isolated from Guangdong environmental samples and chickens from April to May 2013 were highly similar to other H7N9 strains found in eastern China. The H7N9 virus isolated from the clinical patient in Guangdong in August 2013 was divergent from previously identified H7N9 viruses, with the NS and NP genes originating from recent H9N2 viruses circulating in the province. This study provides direct evidence that continuing reassortment occurred and led to the emergence of a novel H7N9 influenza virus in Guangdong, China. These results also shed light on how the H7N9 virus evolved, which is critically important for future monitoring and tracing of viral transmission.

INTRODUCTION

On 30 March 2013, a novel avian influenza A H7N9 virus causing severe human respiratory infections was identified in China. During the outbreak, 133 cases of human infection with the H7N9 virus were reported between March and May 2013, mainly in the Yangtze River Delta area in eastern China (1–3). Subsequently, human infections with the avian influenza H7N9 virus in China came to an apparent halt, with only one case of infection [A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9)] reported on 10 August in Guangdong Province. Preliminary sequence analyses suggest that the H7N9 viruses causing the 2013 outbreak in China were novel reassortants. The results showed that the hemagglutinin (HA) gene originated from avian influenza viruses circulating in ducks in Zhejiang Province, the neuraminidase (NA) gene was related to those of avian influenza viruses isolated from migratory birds, and the six internal genes were from two different groups of H9N2 avian influenza viruses (2, 4, 5).

According to the epidemiology and sequence analyses, H7N9 virus-contaminated live-poultry markets (LPM) are regarded as the major sources of the human infections with the H7N9 virus (6–8). Therefore, after the initial report of H7N9 influenza virus infection in humans in March 2013, environmental sampling programs and enhanced sentinel hospital surveillance were implemented in Guangdong in order to identify possible cases of infection and to analyze the evolution of the virus. In this study, we integrated epidemiological and sequence data from environmental samples from LPM, chickens, and human clinical samples to infer the genetic diversity and evolution of H7N9 influenza viruses in Guangdong, China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection.

Environmental surveillance for the H7N9 virus was performed in LPM in the capital city (Guangzhou) and 21 prefectural-level cities of Guangdong Province from 15 April to 31 May 2013. The Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control (CDC) and local CDCs in each city collected at least 20 samples per week from local LPM. Detailed information is given in Table 1. An enhanced surveillance program for influenza A (H7N9) virus infections was also conducted in 28 sentinel hospitals and 23 collaborating laboratories beginning 16 April in Guangdong, China. Patients with pneumonia of unknown etiology in the sentinel hospitals were reported to the corresponding district CDC, and respiratory specimens were collected. After collection, each swab was placed in a transport medium (M199) with antibiotics and was kept in a cool box before and during shipping to the analysis laboratories.

TABLE 1.

Environmental surveillance of avian influenza viruses in Guangdong Province from April to May 2013

| City | No. of poultry markets | No. of samples collected | No. of positive samples |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | H5 | H7 | H9 | H5/H9 | Hx | |||

| Jieyang | 4 | 140 | 56 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 38 |

| Zhongshan | 5 | 140 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 17 |

| Zhuhai | 5 | 140 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 2 | 18 |

| Qingyuan | 5 | 140 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 49 |

| Shenzhen | 4 | 140 | 44 | 5 | 0 | 24 | 7 | 8 |

| Zhanjiang | 4 | 140 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 24 |

| Shantou | 5 | 140 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 11 |

| Shaoguan | 6 | 210 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 16 |

| Zhaoqing | 5 | 140 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| Shanwei | 4 | 120 | 22 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| Meizhou | 6 | 199 | 28 | 0 | 2 | 17 | 0 | 9 |

| Heyuan | 4 | 140 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 14 |

| Yunfu | 4 | 140 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 4 |

| Jiangmen | 5 | 140 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 6 |

| Huizhou | 4 | 120 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| Yangjiang | 4 | 140 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Shunde | 1 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Foshan | 5 | 152 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Maoming | 4 | 120 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Dongguan | 6 | 140 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Chaozhou | 5 | 172 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guangzhou | 11 | 294 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 19 |

| Total | 106 | 3,235 | 579 | 23 | 2 | 274 | 13 | 267 |

Rapid diagnostics and virus isolation.

Samples were first tested for avian influenza A virus. Influenza A virus subtypes (H5, H7, and H9) were then detected by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) in local CDC laboratories and were further verified by the Guangdong Provincial CDC. H7 virus-positive samples underwent further analysis, and the presence of N9 gene segments was detected by RT-PCR. Swab materials were blindly passaged for 2 to 3 generations in 9- to 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs for virus isolation. Hemagglutinin-positive isolates were collected and were further subtyped by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) and neuraminidase inhibition (NAI) assays using a panel of reference antisera as described by Huang et al. (9). Standard precautions were taken to avoid cross-contamination of samples. All H7 influenza virus isolates from the Meizhou poultry market (n = 2) and a Huizhou patient (n = 1) and seven H9 influenza virus isolates from different LPM were selected. Mono-influenza virus infection (with no infection by the other two virus subtypes) was further confirmed by RT-PCR before full-genome sequencing.

Genomic sequencing.

All eight segments of the selected isolates were sequenced using a next-generation sequencing strategy for influenza A virus with the Ion PGM System and the PathAmp FluA reagents (Life Technologies). The isolation identification (ID) code and information for each virus isolate are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Phylogenetic analysis.

All of the H7N9 virus genome sequences were downloaded from the NCBI Influenza Virus Resource (10) and GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data) databases (accessed 6 December 2013). Maximum-likelihood (ML) trees were estimated for all 8 gene segments (HA, NA, nucleoprotein [NP], basic polymerase proteins 1 and 2 [PB1 and PB2], polymerase [PA], matrix [M], and nonstructural [NS]) by using MEGA, version 6.06, with the generalized time-reversible GTR+G model (11). To assess the robustness of individual nodes on phylogenetic trees, a bootstrap resampling process was used (1,000 replications) using the neighbor-joining method.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The full-genome sequences generated in this study were submitted to GISAID under accession numbers EPI_ISL_148417 and EPI_ISL_151429-151437.

RESULTS

Different HA subtypes of influenza viruses in LPM in Guangdong Province.

A total of 3,235 fecal and swab samples from 106 LPM were collected from 15 April to 31 May 2013 and were screened in the laboratories of local CDCs and the Guangdong Provincial CDC (Table 1). A total of 579 samples (17.9%) were identified as positive for influenza A virus. The H9 subtype virus was identified as the predominant circulating subtype in Guangdong, since 274 samples (8.5% of all environmental samples) from 21 cities were positive for the influenza A (H9) virus. Twenty-three samples from six locations were positive for the H5 virus (Table 1). Samples (n = 13) with both H5 and H9 influenza viruses were occasionally identified. Only two H7N9 virus-positive samples were detected during the surveillance, both from the same LPM in Meizhou city. Subtype identifications ruled out the coexistence of H5, H6, and H9 subtypes in these two H7N9-positive samples.

H7N9 and H9N2 isolates.

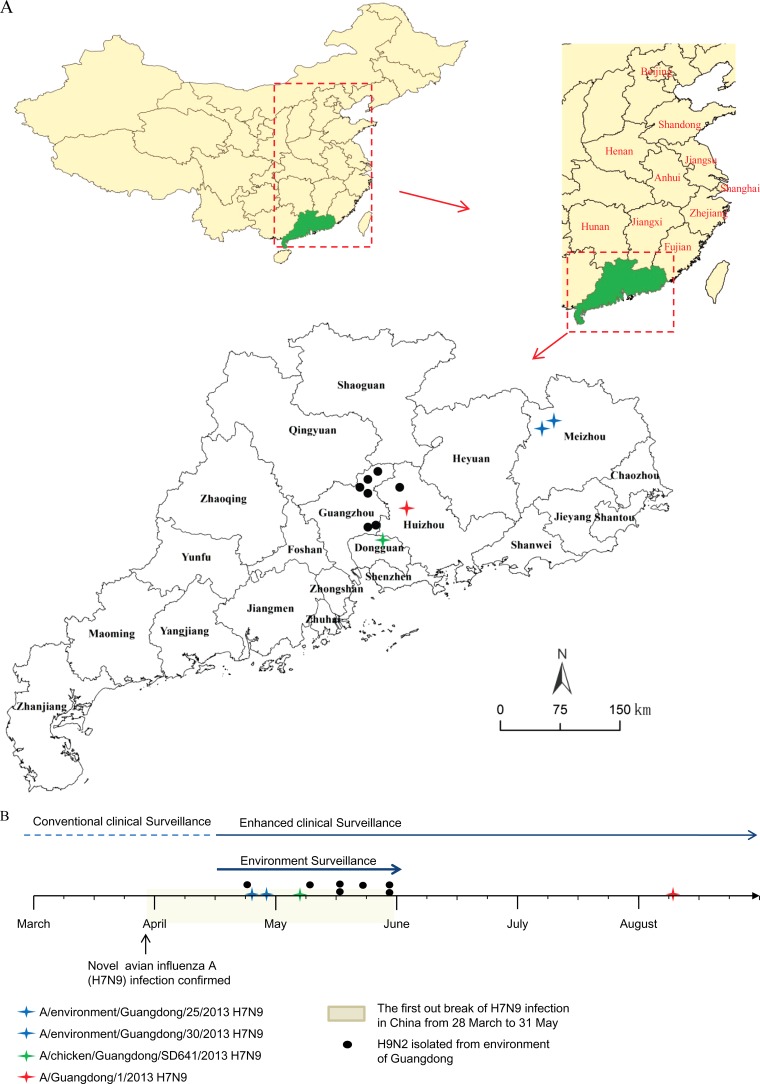

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material, three H7N9 and seven H9N2 viral strains were successfully isolated. Two environmental H7N9 viral strains were isolated from samples collected on 25 April 2013 in an LPM in Meizhou city. One week later, on 5 May 2013, the Guangdong Provincial Center for Animal Disease Control reported that an H7N9 virus infection had been identified in a chicken in Dongguan city, and subsequently the viral sequence was released. The third H7N9 viral strain we isolated was from the first infected human patient in Guangdong. The patient was a 51-year-old woman who worked as a poultry butcher in an LPM in Huizhou city. Her illness began on 28 July 2013. The throat swab was collected on 9 August 2013 and tested positive for influenza A virus (H7N9) by real-time PCR on the same day. The specimens containing the seven H9N2 viral strains were collected from LPM in Huizhou city and two districts of Guangzhou city from 24 April to 28 May 2013 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). RT-PCR was also performed to rule out the coexistence of H5, H6, and H7 subtypes in these samples.

FIG 1.

Distribution (A) and timeline of identification (B) of influenza A H7N9 and H9N2 viruses from LPM and clinical patients in Guangdong Province, China, in 2013. The 10 provinces and/or cities that reported H7N9 virus cases between March and May 2013 are marked in red (A).

Sequence analysis.

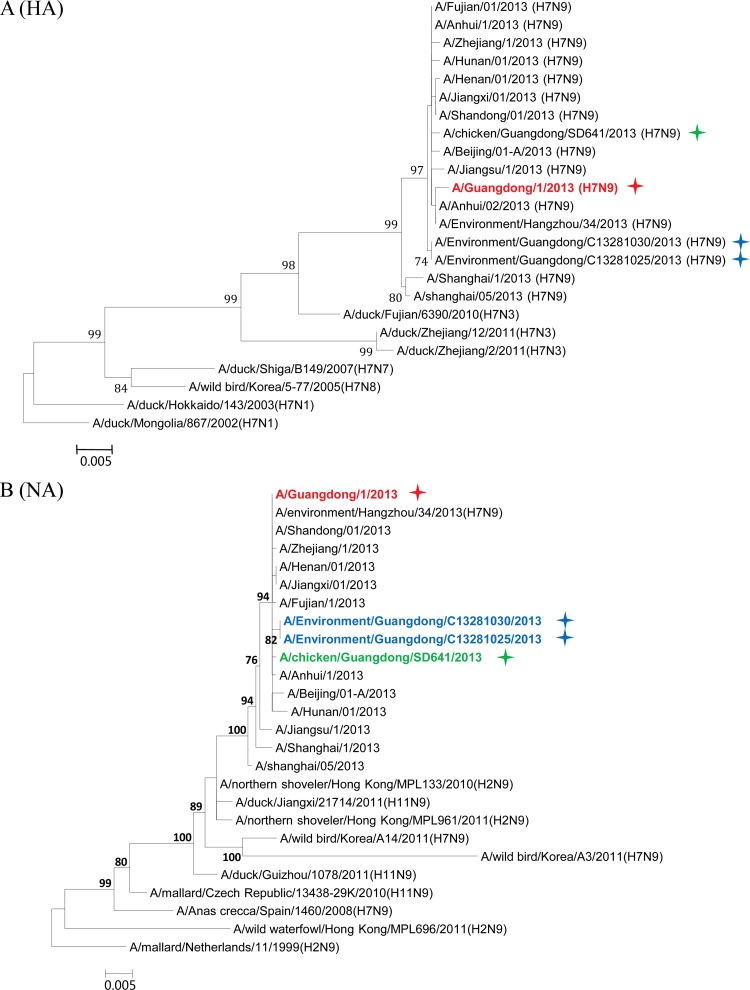

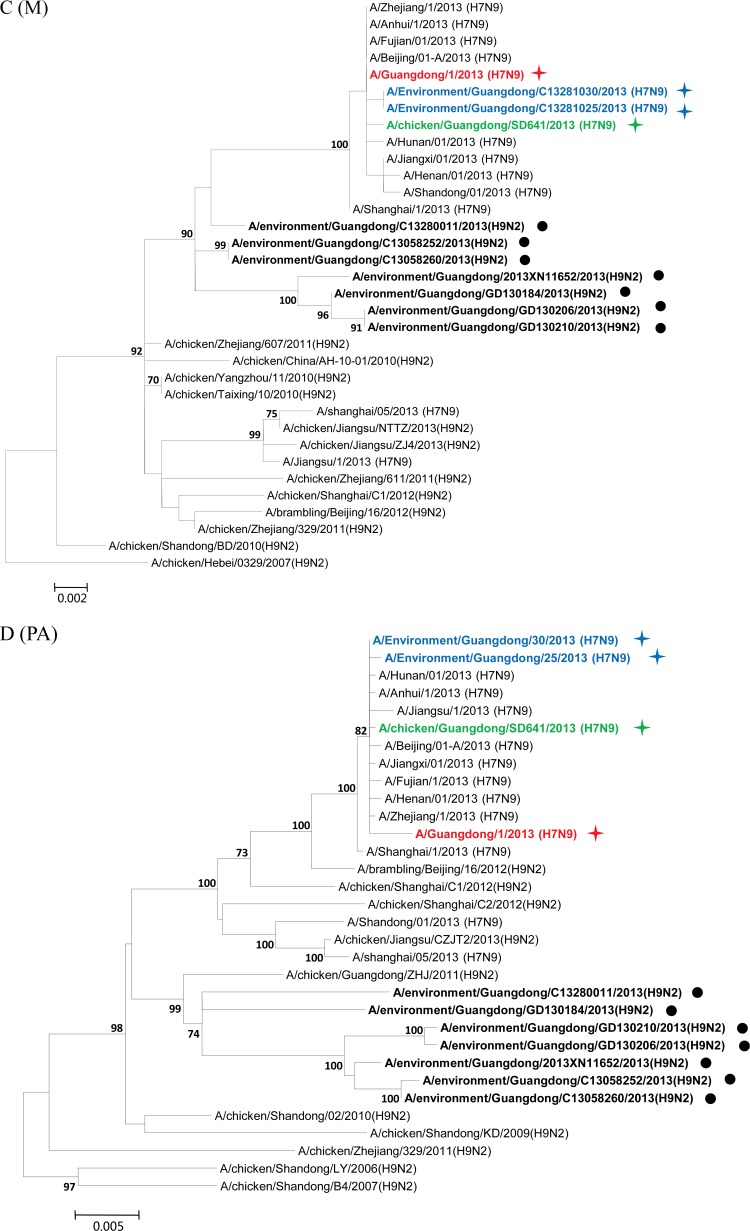

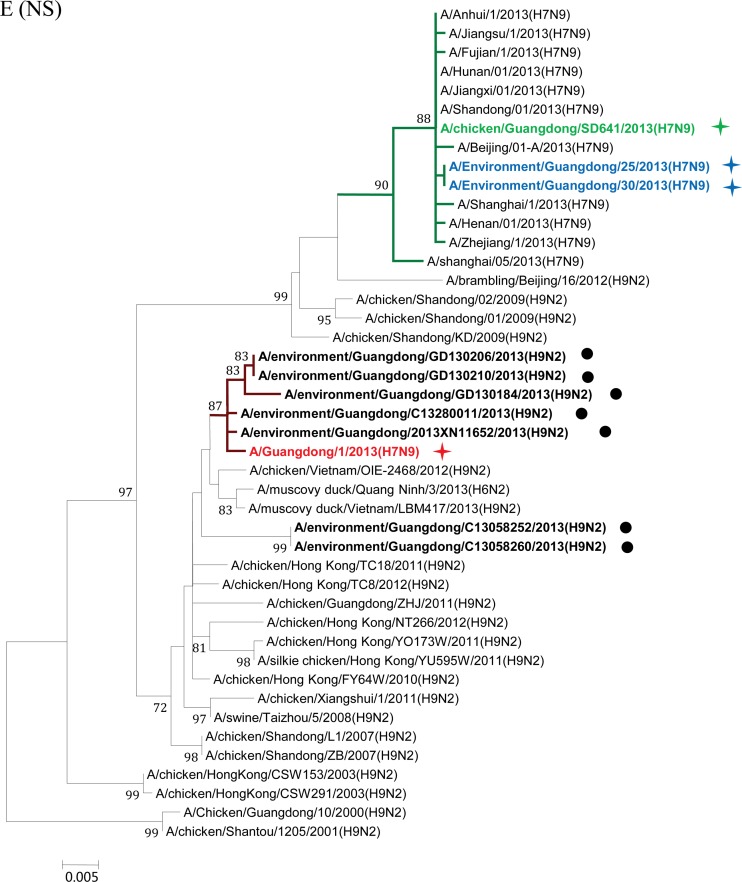

Phylogenetic analyses were performed to elucidate the origin and evolution of H7N9 viruses in Guangdong. With the HA and NA genes, all four strains of the H7N9 viruses from Guangdong fell within a single cluster (Fig. 2A and B) and had high sequence similarity (98.2% to 99.7%) to H7N9 viruses from other regions of China. In particular, the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus isolated from the clinical patient shared the highest nucleotide sequence similarity with the A/Environment/Hangzhou/34/2013 virus, with 100% identity with the NA gene and 99.8% identity with the HA gene. Phylogenetic analyses on the M and PA genes also showed that the four strains of the Guangdong H7N9 virus segregated into a single cluster and shared high sequence similarity with other H7N9 viruses (Fig. 2C and D).

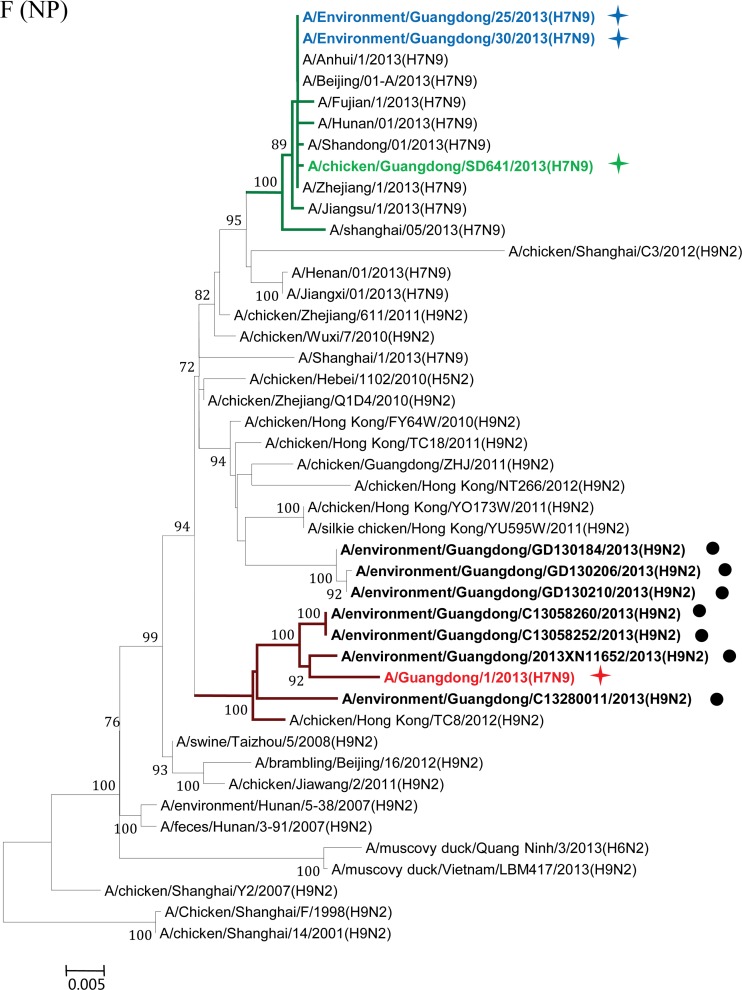

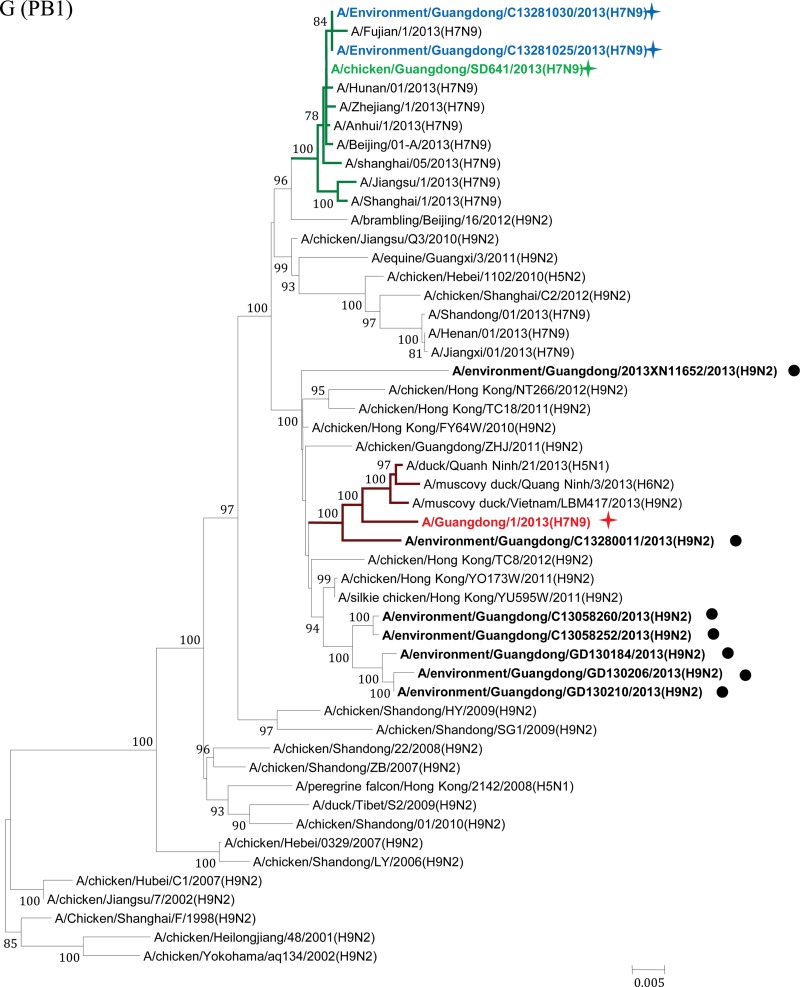

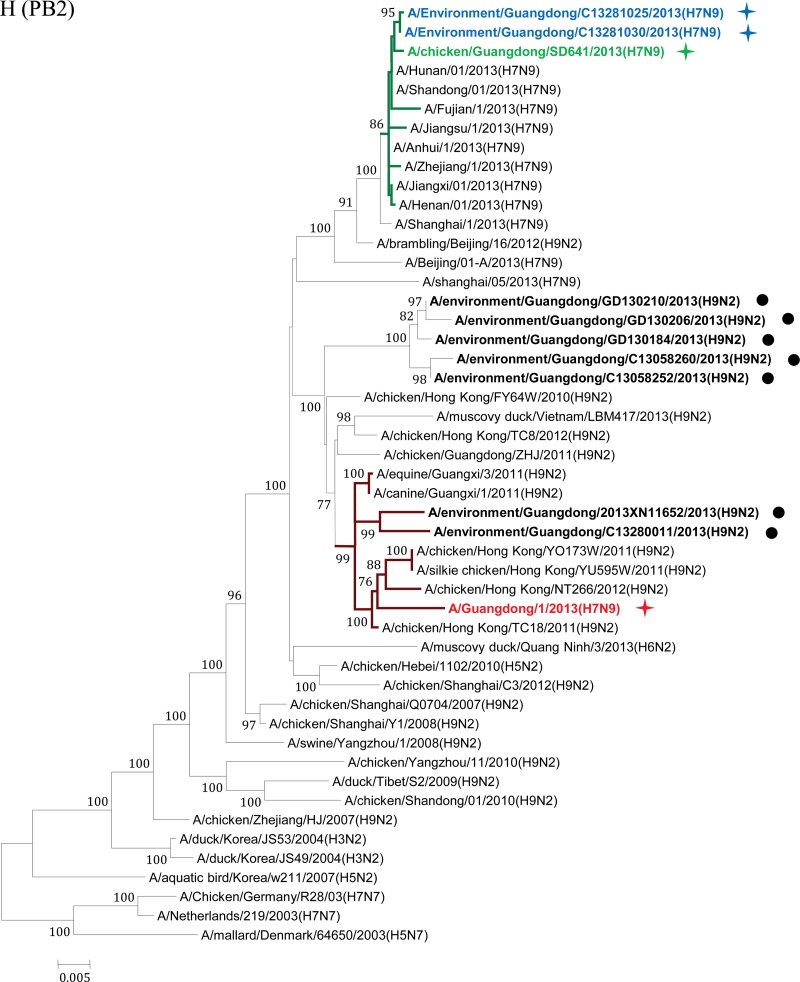

FIG 2.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees for the HA, NA, M, PA, NS, NP, PB1, and PB2 genes of H7N9 isolates. The viruses isolated in this study are marked as in Fig. 1. The separated clusters of major circulating H7N9 viruses and the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. Supporting bootstrap values greater than 70 are shown.

A close examination of the tree topologies with the other four internal genes revealed diversified origins of these internal genes for the H7N9 viruses analyzed. The three H7N9 viral strains [A/environment/Guangdong/25/2013 (H7N9), A/environment/Guangdong/30/2013 (H7N9), and A/chicken/Guangdong/SD641/2013 (H7N9)] isolated from the environmental and chicken samples in Guangdong during the major outbreak period (from March to May 2013) (Fig. 1) were closely related to H7N9 strains previously isolated in other provinces in China and segregated into major H7N9 clusters (Fig. 2E to H). However, the H7N9 virus strain A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9), isolated in the first clinical case in Guangdong in early August, was divergent from previously isolated H7N9 viral strains. In particular, the NS genes of other H7N9 viruses were found to belong to a single cluster (Fig. 2E), whereas the NS gene of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus was outside this group and belonged to a cluster composed of subtype H9N2 viruses from Guangdong identified during April and May 2013 (Fig. 2E; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). It had the highest nucleic acid similarity (99.6%) and amino acid similarity (100%) with the H9N2 strains A/environment/Guangdong/2013XN11652/2013 (H9N2) and A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2). The NP gene of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus was also separated from the NP genes of other H7N9 strains and shared high sequence similarity with those of local H9N2 strains, particularly the A/environment/Guangdong/2013XN11652/2013 (H9N2) virus (98.7%) (Fig. 2F; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). For the PB1 and PB2 genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus, the most similar sequences were found in the H9N2 viral strains isolated from a Muscovy duck in Vietnam in 2013 and from a chicken in Hong Kong in 2011, respectively. The PB1 and PB2 genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus were also clustered around the Guangdong H9N2 strain A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2) but were separated from previously isolated H7N9 viral strains (Fig. 2G and H; see also Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we comprehensively surveyed live-poultry markets in Guangdong Province during the first H7N9 influenza virus outbreak period in 2013. Two H7N9 virus-positive specimens were detected in LPM, followed by identification of H7N9 virus infection in a chicken and in a human patient. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the genetic diversity of H7N9 viruses in Guangdong at different time points and suggested that continuing reassortment with local H9N2 viruses was occurring, leading to the rapid evolution of H7N9 viruses.

As of 31 May 2013, a total of 133 confirmed human infections with the H7N9 virus, including 38 deaths, had occurred in 10 provinces in eastern China (3). Guangdong, the most southern province of China, is 1,200 kilometers away from Shanghai, the epicenter of the H7N9 virus outbreak in 2013 (Fig. 1). From March to May 2013, no clinical H7N9 virus infection case was documented and only three H7N9 virus-positive specimens (two from environmental samples from LPM and one from a chicken) were detected in Guangdong, even though enhanced surveillance was performed. Genetic analyses showed high sequence similarity between these three H7N9 viruses and strains from eastern China, suggesting that the viruses isolated from the Guangdong environment and chicken had a single origin and were most probably transferred through transportation of live poultry from eastern China. It is still unclear why these imported H7N9 viruses did not spread widely in Guangdong at that time. One explanation could be insufficient surveillance. Another could be that these imported H7N9 viruses have limited viability within Guangdong poultry. This would explain the low H7N9 virus-positive rates detected during enhanced environmental surveillance for H7N9 virus (12) and the fact that no clinical infection cases were reported during the period from March to May 2013 in Guangdong.

After May 2013, human infections with H7N9 avian influenza virus in China came to an apparent halt. On 10 August 2013, Guangdong reported the first H7N9 virus infection case in humans, 3 months after the H7N9 virus was initially identified in the Guangdong environment and 4 months after the first human case of H7N9 virus infection was reported in China. Phylogenetic trees showed that the HA, NA, M, and PA genes of the viral strain isolated from the Guangdong patient were segregated into the same clusters as those of previously reported H7N9 strains. However, divergences were observed when we analyzed the other four internal genes (Fig. 2E to H; see also Fig. S1 to S4 in the supplemental material). The NP, NS, PB1, and PB2 genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus were not grouped into the same clusters as other reported H7N9 strains but fell within the same clusters as local Guangdong H9N2 viruses. Previous studies have suggested that at least two steps of sequential reassortment with distinct H9N2 viruses took place to generate the novel H7N9 virus (4, 13). Our results implied that the H7N9 virus was and still is undergoing rapid and continuing genetic reassortment with H9N2 viruses. Because not all the H7N9 viruses identified in other provinces have been fully sequenced, we cannot exclude the possibility that A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9)-like viruses may have existed previously in other regions and may have been imported into Guangdong in July 2013. The current analyses of the NS, NP, PB1, and PB2 genes indicated that none of the H7N9 viruses from other regions of China are like the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9)-like virus. BLAST and phylogenetic analyses of the NS and NP genes suggested that these two internal genes for the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus most likely originated from local H9N2 viruses (Fig. 2E and F). The use of local H9N2 virus internal gene cassettes might be one of the essential requirements for the easy spread of the H7N9 viruses among poultry populations of Guangdong, which finally led to the first H7N9 virus infection of a human in Guangdong. Moreover, our environmental surveillance data suggested that a higher ratio of H9N2 viruses had been detected in Guangdong LPM than in other regions of China (Table 1) (14). Since live poultry was the major source of H7N9 viruses (8, 15–17), the coexistence of H9N2 viruses in that susceptible population was likely to generate appropriate conditions for the emergence of novel reassortment variants (6). From this, we proposed that the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus was most likely a product of the most recent reassortment between a novel H7N9 virus and the local H9N2 viruses.

Close examinations have determined that the NS and NP genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus were most closely related to the local H9N2 strains A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2) and A/environment/Guangdong/2013XN11652/2013 (H9N2). As shown in Fig. 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material, the A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2) and A/environment/Guangdong/2013XN11652/2013 (H9N2) viruses were isolated in the same city where A/Guangdong/1/2013(H7N9) was identified (Huizhou) or in an adjacent city (Guangzhou). In the phylogenetic trees of the PB1 and PB2 genes, the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus also grouped into the same cluster with the A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2) virus, although the most closely related viral strains were found to be H9N2 viruses isolated in adjacent regions, Vietnam and Hong Kong, respectively (Fig. 2E to H). In other words, the NS, NP, PB1, and PB2 genes of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus were more closely related to those of H9N2 influenza viruses such as the A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2) virus in Guangdong than to those of the H7N9 viruses isolated previously in eastern China. Because only a small proportion of local Guangdong H9N2 strains have been fully sequenced, we believe that more related local strains might have been missed. Based on the observations presented above, we propose a continuing reassortment model for the H7N9 virus in Guangdong. Following the importation of the H7N9 viruses into the Guangdong environment and chicken populations around April 2013, the virus began to recruit internal genes of local H9N2 viruses [A/environment/Guangdong/C13280011/2013 (H9N2)-like virus] so as to adapt to the poultry population in Guangdong Province. Heavy contamination with H9N2 viruses in Guangdong poultry markets could facilitate and accelerate the reassortment process. Thereafter, the local H9N2 virus internal genes were better adapted to the H7N9 viruses in Guangdong and finally formed the ancestor of the A/Guangdong/1/2013 (H7N9) virus identified in early August 2013.

Overall, this study provides direct evidence that rapid and continuing reassortment with local Guangdong H9N2 viruses occurred, leading to the emergence of a novel H7N9 influenza virus in Guangdong, China. Current epidemiology and experimental results suggest that the H7N9 virus has limited capacity for human-to-human transmission and chicken-to-chicken or chicken-to-mammal transmission (18–20). Reassortment enables viruses to change their genetic architectures very quickly, which may, in turn, increase their ability to infect chickens or humans. Hence, extensive surveillance of live-poultry markets and ongoing human infections remains essential for early warning of novel reassortants and sequence mutations of H7N9 viruses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the 12th 5-Year-Plan major projects of China's Ministry of Public Health, grant 2012zx10004-213, and by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 May 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00630-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen Y, Liang W, Yang S, Wu N, Gao H, Sheng J, Yao H, Wo J, Fang Q, Cui D, Li Y, Yao X, Zhang Y, Wu H, Zheng S, Diao H, Xia S, Chan KH, Tsoi HW, Teng JL, Song W, Wang P, Lau SY, Zheng M, Chan JF, To KK, Chen H, Li L, Yuen KY. 2013. Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. Lancet 381:1916–1925. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60903-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, Chen J, Jie Z, Qiu H, Xu K, Xu X, Lu H, Zhu W, Gao Z, Xiang N, Shen Y, He Z, Gu Y, Zhang Z, Yang Y, Zhao X, Zhou L, Li X, Zou S, Zhang Y, Yang L, Guo J, Dong J, Li Q, Dong L, Zhu Y, Bai T, Wang S, Hao P, Yang W, Han J, Yu H, Li D, Gao GF, Wu G, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Shu Y. 2013. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:1888–1897. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu W, Yang K, Qi X, Xu K, Ji H, Ai J, Ge A, Wu Y, Li Y, Dai Q, Liang Q, Bao C, Bergquist R, Tang F, Zhu Y. 2013. Spatial and temporal analysis of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China, 2013. Euro Surveill. 18(47):pii=20640 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu A, Su C, Wang D, Peng Y, Liu M, Hua S, Li T, Gao GF, Tang H, Chen J, Liu X, Shu Y, Peng D, Jiang T. 2013. Sequential reassortments underlie diverse influenza H7N9 genotypes in China. Cell Host Microbe 14:446–452. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam TT, Wang J, Shen Y, Zhou B, Duan L, Cheung CL, Ma C, Lycett SJ, Leung CY, Chen X, Li L, Hong W, Chai Y, Zhou L, Liang H, Ou Z, Liu Y, Farooqui A, Kelvin DJ, Poon LL, Smith DK, Pybus OG, Leung GM, Shu Y, Webster RG, Webby RJ, Peiris JS, Rambaut A, Zhu H, Guan Y. 2013. The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China. Nature 502:241–244. 10.1038/nature12515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X, Jin T, Cui Y, Pu X, Li J, Xu J, Liu G, Jia H, Liu D, Song S, Yu Y, Xie L, Huang R, Ding H, Kou Y, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Xu X, Yin Y, Wang J, Guo C, Yang X, Hu L, Wu X, Wang H, Liu J, Zhao G, Zhou J, Pan J, Gao GF, Yang R. 2014. Influenza H7N9 and H9N2 viruses: coexistence in poultry linked to human H7N9 infection and genome characteristics. J. Virol. 88:3423–3431. 10.1128/JVI.02059-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Yu X, Pu X, Xie L, Sun Y, Xiao H, Wang F, Din H, Wu Y, Liu D, Zhao G, Liu J, Pan J. 2013. Environmental connections of novel avian-origin H7N9 influenza virus infection and virus adaptation to the human. Sci. China Life Sci. 56:485–492. 10.1007/s11427-013-4491-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, Chen Z, Li F, Wu H, Xiang N, Chen E, Tang F, Wang D, Meng L, Hong Z, Tu W, Cao Y, Li L, Ding F, Liu B, Wang M, Xie R, Gao R, Li X, Bai T, Zou S, He J, Hu J, Xu Y, Chai C, Wang S, Gao Y, Jin L, Zhang Y, Luo H, Yu H, Gao L, Pang X, Liu G, Shu Y, Yang W, Uyeki TM, Wang Y, Wu F, Feng Z. 2014. Epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 370:520–532. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang K, Zhu H, Fan X, Wang J, Cheung CL, Duan L, Hong W, Liu Y, Li L, Smith DK, Chen H, Webster RG, Webby RJ, Peiris M, Guan Y. 2012. Establishment and lineage replacement of H6 influenza viruses in domestic ducks in southern China. J. Virol. 86:6075–6083. 10.1128/JVI.06389-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao Y, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Kiryutin B, Zaslavsky L, Tatusova T, Ostell J, Lipman D. 2008. The Influenza Virus Resource at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. J. Virol. 82:596–601. 10.1128/JVI.02005-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30:2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan J, Tang X, Yang Z, Wang M, Zheng B. 2014. Enhanced disinfection and regular closure of wet markets reduced the risk of avian influenza A virus transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58:1037–1038. 10.1093/cid/cit951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Zhang Z, Weng Z. 2013. Rapid reassortment of internal genes in avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57:1059–1061. 10.1093/cid/cit414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song R, Pang X, Yang P, Shu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Chen Z, Liu J, Cheng J, Jiao Y, Jiang R, Lu L, Chen L, Ma J, Li C, Zeng H, Peng X, Huang L, Zheng Y, Deng Y, Li X. 2014. Surveillance of the first case of human avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in Beijing, China. Infection 42:127–133. 10.1007/s15010-013-0533-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J, Jin M, Zhang P, Liu J, Wang L, Wen D, Wu X, Liu G, Zou Y, Lv X, Dong X, Shao B, Gu S, Zhou D, Leng Q, Zhang C, Lan K. 2013. Epidemiological link between exposure to poultry and all influenza A(H7N9) confirmed cases in Huzhou city, China, March to May 2013. Euro Surveill. 18(20):pii=20481 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20481 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao CJ, Cui LB, Zhou MH, Hong L, Gao GF, Wang H. 2013. Live-animal markets and influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 368:2337–2339. 10.1056/NEJMc1306100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Wang L, Hu W, Ding F, Sun H, Li S, Huang L, Li C. 2013. Epidemiologic characteristics of cases for influenza A(H7N9) virus infections in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57:619–620. 10.1093/cid/cit277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Kiso M, Fukuyama S, Nakajima N, Imai M, Yamada S, Murakami S, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Sakoda Y, Takashita E, McBride R, Noda T, Hatta M, Imai H, Zhao D, Kishida N, Shirakura M, de Vries RP, Shichinohe S, Okamatsu M, Tamura T, Tomita Y, Fujimoto N, Goto K, Katsura H, Kawakami E, Ishikawa I, Watanabe S, Ito M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Sugita Y, Uraki R, Yamaji R, Eisfeld AJ, Zhong G, Fan S, Ping J, Maher EA, Hanson A, Uchida Y, Saito T, Ozawa M, Neumann G, Kida H, Odagiri T, Paulson JC, Hasegawa H, Tashiro M, Kawaoka Y. 2013. Characterization of H7N9 influenza A viruses isolated from humans. Nature 501:551–555. 10.1038/nature12392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2013. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature 501:556–559. 10.1038/nature12391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku KB, Park EH, Yum J, Kim HM, Kang YM, Kim JC, Kim JA, Kim HS, Seo SH. 2014. Transmissibility of novel H7N9 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses between chickens and ferrets. Virology 450–451:316–323. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.