ABSTRACT

We report that the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) high-molecular-weight tegument protein (HMWP, pUL48; 253 kDa) and the HMWP-binding protein (hmwBP, pUL47; 110 kDa) can be recovered as a complex from virions disrupted by treatment with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.5 M NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, and 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]. The subunit ratio of the complex approximates 1:1, with a shape and structure consistent with an elongated heterodimer. The HMWP/hmwBP complex was corroborated by reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments using antipeptide antibodies and lysates from both infected cells and disrupted virus particles. An interaction of the amino end of pUL48 (amino acids [aa] 322 to 754) with the carboxyl end of pUL47 (aa 693 to 982) was identified by fragment coimmunoprecipitation experiments, and a head-to-tail self-interaction of hmwBP was also observed. The deubiquitylating activity of pUL48 is retained in the isolated complex, which cleaves K11, K48, and K63 ubiquitin isopeptide linkages.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV, or human herpesvirus 5 [HHV-5]) is a large DNA-containing virus that belongs to the betaherpesvirus subfamily and is a clinically important pathogen. Defining the constituent elements of its mature form, their organization within the particle, and the assembly process by which it is produced are fundamental to understanding the mechanisms of herpesvirus infection and developing drugs and vaccines against them. In this study, we report isolating a complex of two large proteins encoded by HCMV open reading frames (ORFs) UL47 and UL48 and identifying the binding domains responsible for their interaction with each other and of pUL47 with itself. Our calculations indicate that the complex is a rod-shaped heterodimer. Additionally, we determined that the ubiquitin-specific protease activity of the ORF UL48 protein was functional in the complex, cleaving K11-, K48-, and K63-linked ubiquitin dimers. This information builds on and extends our understanding of the HCMV tegument protein network that is required to interface the HCMV envelope and capsid.

INTRODUCTION

In herpesviruses, the region of the virion interfacing the nucleocapsid and envelope is called the tegument (1). Its constituents have been identified or deduced by comparing mature (virions), immature (e.g., A, B, and C capsids and procapsids), and aberrant (e.g., noninfectious enveloped particles [NIEPs], dense bodies [DBs], and light particles [LPs]) forms of the virus (2–10), by analyzing virions whose outer layers have been partially stripped away by physical or chemical treatment (2, 11), and by an array of microscopy, genetic, and immunological approaches (12, 13).

The number and organization of proteins in the herpesvirus tegument are more complex than the “matrix” layer of smaller enveloped viruses and include interactions and networks with envelope glycoproteins, with other tegument proteins, and with the capsid (12, 14–18). Many of the virion phosphoproteins and several enzymatic and regulatory activities localize to the tegument, and a working model of the physical and functional interactions of these proteins is emerging (19–22). Considering their importance during virus movement through the cytoplasm following entry and again during capsid maturation and envelopment (23–30), it is likely that a more complete understanding of the tegument protein network will broaden insight into both stages of replication.

In human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) there at least two tegument proteins closely associated with the capsid. One of these is the basic phosphoprotein (BPP, phosphoprotein 150 [pp150], pUL32; 112 kDa), which binds to the capsid triplex through its amino end (12, 14, 15, 31–33), helping to stabilize the nucleocapsid during maturation (34, 35), but which has no recognized counterpart in the alpha- and gammaherpesviruses. The other is the high-molecular-weight protein (HMWP, pUL48; 253 kDa) encoded by HCMV open reading frame (ORF) UL48 (36), which has counterparts in all herpesviruses and is the focus of this report.

Early work identified and characterized the protypic homolog of this herpes group-common protein, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) VP1–3 (VP1/2, pUL36; 336 kDa), as a virion constituent (2), tightly associated with the capsid (2, 3, 37), whose function affects both early and late stages of replication (38, 39). More recent work has established that its counterparts in the other herpesviruses are encoded by the longest ORF in each genome, that it participates in net-like (HCMV) or penton-associated filamentous density features adjacent to the surface of the capsid (12, 14, 17), that it interacts with the dynein motor system to aid movement of the capsid through the cytoplasm toward the nuclear pore (40), that it has a role in releasing DNA from the capsid (38, 39, 41), that it is required for final maturation and envelopment to form infectious virus (41–43), and that its amino end contains ubiquitin-specific cysteine protease (deubiquitylase [DUB]) activity (44–47).

During the course of studying a CMV virion-associated protein kinase (48), we found that under moderate denaturing conditions, HMWP cosedimented during gradient centrifugation with a tegument protein called the HMWP-binding protein (hmwBP, pUL47; 110 kDa), encoded by the adjacent, partially overlapping reading frame. In this report we document the recovery of these proteins as a complex, establish the size and subunit composition of the complex, identify regions of subunit interaction, and test the deubiquitylating activity of the complex.

(A preliminary report of our initial findings was given at the 15th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Virology, London, Ontario, Canada, 1996 [49]. Part of this research was conducted by M.-E. Harmon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. from The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 1998.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, virus, and radiolabeling.

Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine calf serum (Thermo Fisher-HyClone, Waltham, MA) and Pen/Strep (1:100 dilution of 10,000 U/ml penicillin and 10,000 μg/ml streptomycin; Life Technologies) (50). Wild-type human cytomegaloviruses (HCMV strain AD169 [VR-538; ATCC, Manassas, VA]) and bacmid-derived viruses JTB11 and JTB27 (see below) were propagated as previously described (44). Metabolic radiolabeling was done by adding 10 mCi/ml [35S]methionine (no. 51001H [ICN, Cleveland, OH] or no. NEG072007MC [Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA]) or 10 mCi/ml [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (no. 51006; ICN) to the culture medium 48 h prior to harvesting on day 7 postinfection.

Plasmid construction.

HCMV UL47 (ATG at nucleotide 60387, stop at 63338) (51) was subcloned from the M fragment of an HCMV HindIII genomic DNA library (gift of M. Chee and B. Barrell) by digestion first with SpeI and SnaBI to obtain a 3.4-kb fragment containing the UL47 ORF. This fragment was then ligated 3′ of the T7 promoter into compatible XbaI/SmaI-digested pGEM-4Z (Promega, Madison, WI).

To clone the carboxyl end of UL47, nucleotides 62467 to 62897 were PCR amplified using forward and reverse primers that added a BamHI and an EcoRI site to the respective ends of the fragment, and the BamHI/EcoRI-digested product was ligated into pGEM-4Z. The appropriate HindIII/XhoI fragment from the resulting clone was used to replace that removed from the full-length UL47 clone to produce a final product that represents UL47 from nucleotides 62467 to the end at position 63338.

HCMV UL48 (ATG at nucleotide 63335, stop at 70057) (51) was cloned into pGEM-7Z as follows. The 5′ end of the gene, contained within a 1.3-kb BsaW1/HindIII subfragment of the HindIII M fragment, was cloned into AvaI/HindIII-digested pGEM-3Z. The 3′ remainder of the gene was subcloned from the HindIII F fragment (gift of M. Chee and B. Barrell) as a HindIII/SstI fragment into HindIII/SstI-digested pGEM-7Z. This clone was linearized with HindIII and EcoRI and ligated to a HindIII/EcoRI 1.3-kb fragment derived from the 5′ UL48 construct.

An expression clone for the 3′ half of UL48 was made by PCR amplifying nucleotides 66659 to 67071, cleaving the resulting fragment at new BamHI and EcoRI sites introduced by the primers, and using the resulting product to replace the BamHI/EcoRI fragment in the 3′ UL48 clone described in the previous paragraph. The final construct was a UL48 truncation with a new translational start site at nucleotide 66659.

Bacmid-derived viruses.

The two viruses used to test for deubiquitylating activity of the pUL47/48 complex were derived from bacmids AD169-US2-11-EGFP-loxP (where EGFP is enhanced green fluorescent protein) (52) and a pUL48/Cys24Ile mutant described before (44). In each, the EGFP ORF was replaced with an ORF encoding a kanamycin (KAN) resistance gene, eliminating expression of the GFP marker during virus infection. Flanking recombination arms were added to the KAN cassette by PCR, using a counterselection bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) modification kit from Gene Bridges (Gene Bridges GmbH BioZ, Dresden, Germany), based on the Redα/β recombination method (53, 54), to select the KAN-substituted bacmid, JTB11. Bacmid JTB27 was made the same way but starting with the HCMV pUL48/Cys24Ile mutant bacmid. Virus was reconstituted and sequence verified from the bacmids (44).

Particle recovery, disruption, and rate-velocity sedimentation.

Extracellular HCMV virions and noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs) (5) were recovered directly from the medium by banding in sucrose or glycerol/tartrate gradients as described before (55). Particles were then concentrated by pelleting (35,000 rpm, 2 h, 4°C; Beckman SW55 rotor), frozen at −80°C, suspended in particle disruption buffer ([PDB] 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) (e.g., 300 μl/virion pellet from one T150 flask), and kept on ice for 30 to 60 min with intermittent vortex mixing and shearing through a 27-gauge needle. The lysate was clarified (16,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the resulting supernatant was layered onto a 5 to 20% glycerol (vol/vol; in PDB) gradient and subjected to centrifugation (40,000 rpm, 35 to 40 h, 4°C) using a Beckman SW41 rotor.

Gradients were collected from the top in 0.5-ml fractions using a gradient fractionator (no. 185; ISCO, Lincoln, NE), and the fractions were either (i) immediately diluted with one-third volume of 4-fold concentrated Laemmli protein sample buffer (4× buffer is 8% SDS, 40% β-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol, 100 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 0.04% bromophenol blue) and stored at −80°C until analyzed or (ii) sampled immediately to test in diubiquitin (di-Ub) cleavage assays (see below) or to evaluate by SDS-PAGE after the addition of one-third volume of modified protein sample buffer (3 parts NP0007 [Life Technologies, Novex] with 2 parts 1 M DTT).

Gel filtration chromatography.

A 0.5- by 36-cm column packed at 4°C with a slurry of Sephacryl S-300 HR resin (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, England) was equilibrated overnight at 4°C in PDB lacking DTT with constant buffer flow. After calibration with marker proteins (no. 17-0441-01 and 17-0442-01; Pharmacia Biotech), the column was equilibrated with PDB, and 35S-radiolabeled virus prepared and disrupted as described above was passed through and collected in 60 0.5-ml fractions. Proteins in each fraction were identified by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

Antisera.

Three antipeptide antisera were produced in rabbits, as described before (56), against synthetic peptides representing the following: (i) amino acids (aa) 155 to 170 of the UL47 protein (anti-UL47N′), (ii) the 16 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of the predicted UL47 protein (anti-UL47C′), and (iii) amino acids 278 to 295 of the predicted UL48 product (anti-UL48N′). Rabbit antibodies to ubiquitin were from Life Technologies (no. 701339; Life Technologies, Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation.

[35S]methionine-radiolabeled infected cells were scraped into the medium and collected by centrifugation (1m500 × g, 10 min, 4°C). Radiolabeled virions and NIEPs were recovered and concentrated as described above. Cell and virion pellets were disrupted in 0.5 ml of PDB, clarified (16,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), combined with antiserum (10 μl of antiserum/100 μl of lysate), and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. One hundred microliters of protein A-Sepharose beads (no. P3391; Sigma) (50 mg of beads/ml of calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline [CMF-PBS]) with 0.02% NaN3 was added to the reaction mixtures and incubated with occasional mixing for an additional hour at room temperature. Bead-bound immune complexes were washed three times with ice-cold wash buffer (2 M KCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40), transferred to fresh tubes, and washed once more in the same buffer and then a final time in CMF-PBS containing 0.5% deoxycholate (DOC) and 1% NP-40. Proteins were dissociated from the beads and prepared for SDS-PAGE by addition of concentrated (2×) Laemmli protein sample buffer and heating for 3 min in a boiling water bath.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western immunoassays.

Proteins were separated electrophoretically in SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) using either lab-prepared gels and buffers (5) or precast 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gradient gels and morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer (NP0323 and NP0002; Life Technologies, Novex) and modified protein sample buffer (57). Proteins stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) or SYPRO-ruby (SYPRO-R) were imaged and quantified by using Kodak Gel Logic 200 hardware and software.

Western immunoassays were done as previously described (57). The membranes were Immobilon-P (Millipore, Billerica, MA) or 0.2-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) sandwiches (LC2002; Life Technologies, Novex); the transfer buffer (NP0006; Life Technologies, Novex) contained 10% methanol; time/voltage of transfer was 90 min/30 V, and bound antibodies were detected with 125I-protein A (no. IM144 [GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, England] or NEX146025mc [Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA]) and visualized by phosphorimaging or fluorography. When Western immunoassays were done with samples containing [35S]methionine-radiolabeled proteins, an autoradiographic image or phosphorimage of the blot was made to detect all proteins prior to antibody probing. Subsequent to probing, a sheet of 0.005-in.-thick acetate was placed between the blot and the film or phosphorimaging plate to selectively block detection of the weaker 35S emission without significantly diminishing detection of the 125I-protein A signal.

[35S]methionine-radiolabeled proteins in dried gels were detected by autoradiography or by fluorography after the gel was soaked in 1 M sodium salicylate for 1 h prior to drying (58). Autoradiographic exposure was at room temperature; fluorographic exposure was at −80°C. Phosphorimaging (Fuji BAS 1000 phosphorimager with MacBas, version 2.0 or 2.2, software; Stamford, CT) was also used to detect and quantify radiolabeled proteins in dried gels and to detect and quantify the 125I-protein A reporter in Western immunoassays.

In vitro protein synthesis and fragment coimmunoprecipitation.

The ORF UL47 and ORF UL48 pGEM constructs described above were linearized by cleavage downstream of their coding sequences and expressed in coupled in vitro transcription and translation reactions in a T7 TNT rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Madison, WI) containing [35S]methionine (ICN), according to the manufacturer's instructions. To produce carboxyl deletions of the proteins, their plasmid DNAs were linearized by cleavage within their ORFs prior to protein expression. An unexplained 40-kDa protein resulting from premature termination of translation was observed in some TNT reaction products using ORF UL48 constructs. The resulting proteins were mixed in the combinations described in Results and summarized in Fig. 5A, incubated for 3 h at 30°C, and prepared for immunoprecipitation by dilution in 100 μl of homogenization buffer (HB; 40 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 0.1 M KCl, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA]) and clarification (16,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). One microliter of antiserum was added to the clarified preparation, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, combined with 80 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (50 mg/ml in CMF-PBS), and incubated an additional 30 min at room temperature. The bead-bound immune complexes were then washed three times with HB, transferred to fresh tubes and washed twice more, and stripped from the beads by the addition of 2× Laemmli protein sample buffer and heating for 3 min in a boiling water bath.

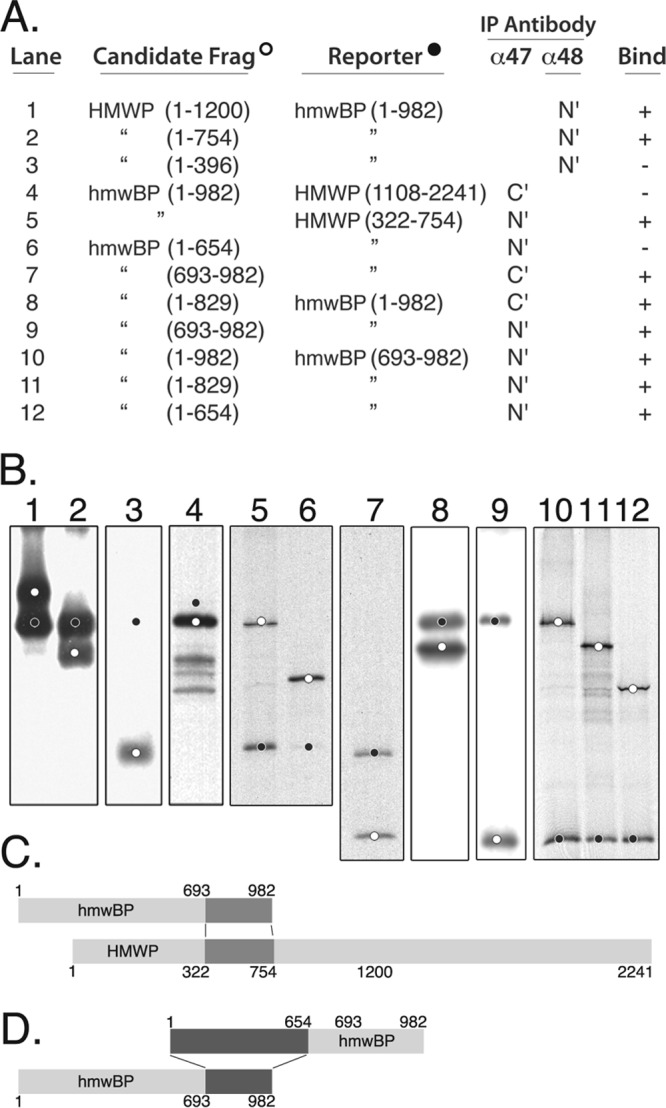

FIG 5.

Carboxyl end of hmwBP forms a complex with the amino end of HMWP, and hmwBP self-interacts head to tail. (A) Full-length and shorter fragments of HMWP and hmwBP were synthesized in vitro with [35S]methionine added, coincubated in candidate/reporter pairs, and immunoprecipitated (IP) using antibodies anti-UL48N′ (α48, N′; lanes 1 to 3), anti-UL47N′ (α47, N′; lanes 5, 6, and 9 to 12), or anti-UL47C′ (α47, C′; lanes 4, 7, and 8). (B) Immune complexes listed in panel A were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and a composite of autoradiograms prepared from the resulting gels is shown. Lanes 1 to 7 display HMWP-hmwBP interactions; lanes 8 to 12 display self-interactions of hmwBP. Candidate fragments are indicated by white dots; reporter fragments, or their expected positions (lanes 3, 4, and 6), are indicated by black dots. (C) Model summarizing results in panel B for interactions of HMWP with hmwBP. Interactive domains are highlighted in dark gray. (D) Model summarizing results in panel B for interacting domains within hmwBP (highlighted in dark gray).

Di-Ub cleavage assays.

DUB activity in gradient fractions was identified by the in vitro cleavage of diubiquitin (di-Ub) to mono-Ub. Samples (50 μl) taken from gradient fractions collected following rate-velocity sedimentation of disrupted virions (see above) were combined with 1 μl of K63-linked di-Ub substrate (5 μM; synthesized and provided by Cynthia Wolberger, John Hopkins Medical Institute [JHMI]), and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Material pelleted onto the bottom of the tube was suspended in 0.5 ml (volume equaling that of gradient fractions) of 20% glycerol (vol/vol, in PDB). A sample of the starting material layered onto the gradient was diluted 2-fold with PDB to make it volumetrically proportional to the gradient fractions.

Reactions were stopped by the addition of one-third volume of modified protein sample buffer, and the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western immunoassay using anti-Ub. Data were obtained from the assay by phosphorimaging, and approximations of DUB activity were calculated as the amount of product mono-Ub detected relative to the amount of substrate pUL48 detected. Factors found to influence the specificity, reproducibility, and quantification of these assays for ubiquitin in particular included (i) membrane type and time of electrotransfer, (ii) nature of anti-Ub antibodies (sensitivity), (iii) nature of secondary reagent used to detect bound IgG, (iv) high concentrations of NP-40 in sample interfering with Western detection of Ub, and (v) uniform dispersal and solubilization of material pelleted during centrifugation. Differential avidity of the anti-Ub antibodies for di- and mono-Ub and their different linkage forms (i.e., K11, K48, and K63) is also possible but was not tested.

RESULTS

The HCMV tegument proteins studied in this work (pUL47 and pUL48) have counterparts in all herpesviruses but with different ORF nomenclature and different sizes. To simplify their discussion across the herpesvirus family, we suggested names based on shared properties (59). The larger of the two HCMV proteins in the complex reported here is a homolog of the largest protein encoded by each herpesvirus genome and is called the high-molecular-weight protein (HMWP). Its binding partner, established to have a homolog encoded by an adjacent gene in all herpesvirus genomes, is called the HMWP-binding protein (hmwBP). We use these names, except when differentiating between homologs in other herpesviruses, and refer to their complex as HMWP/hmwBP.

HMWP and hmwBP cosediment following virion disruption.

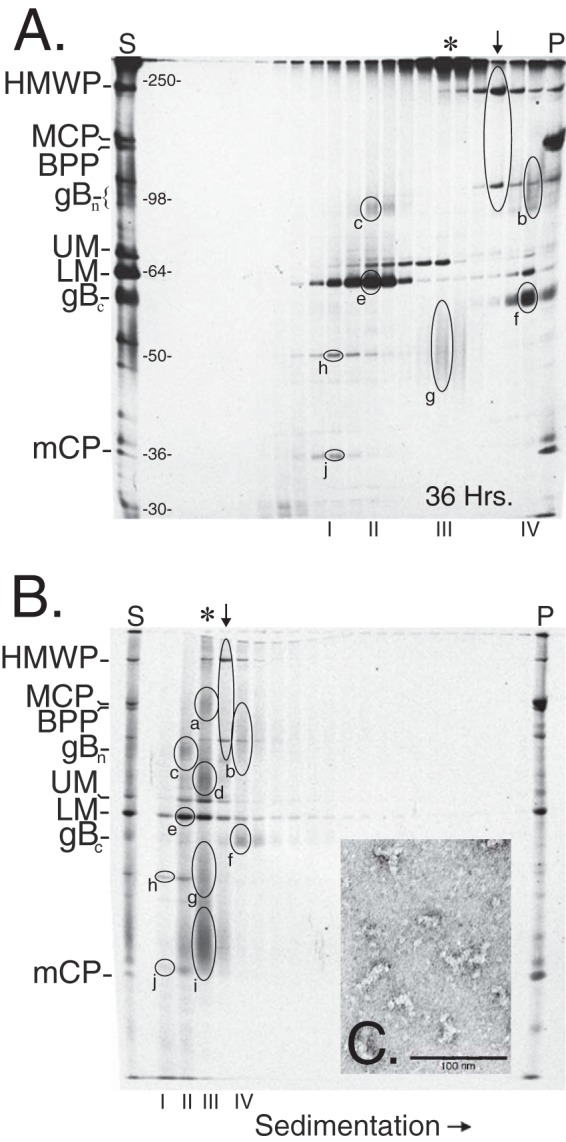

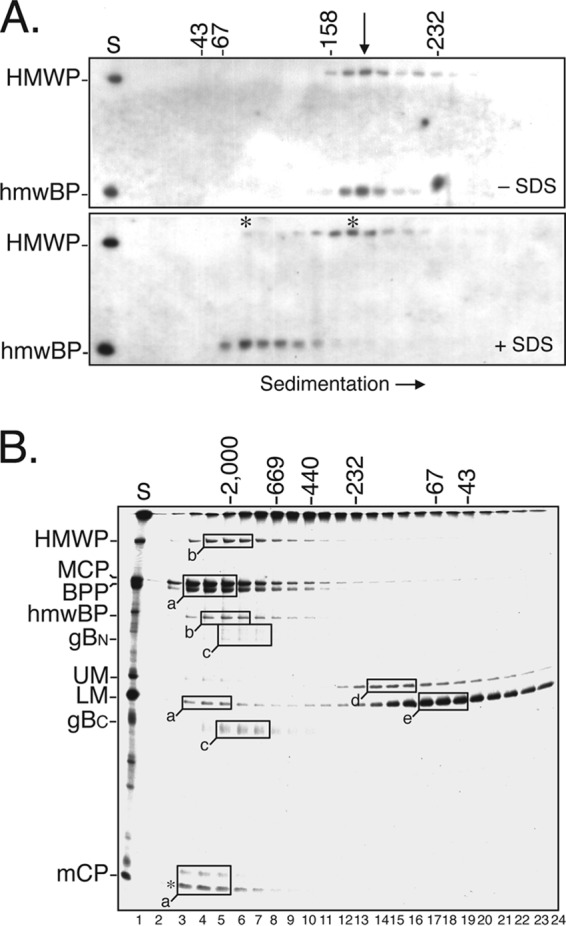

Pilot studies indicated that treating virions or virion-like noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs) with a mixture of 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 M NaCl, and 10 mM DTT substantially disrupted their structure. When such preparations from [35S]methionine-radiolabeled particles were separated by glycerol gradient sedimentation and the protein distribution in the gradient was determined by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography, two proteins with electrophoretic mobilities approximating those of pUL47 (110 kDa) and pUL48 (253 kDa) were found to cosediment toward the bottom of the gradient (Fig. 1A, arrow) (60). The highest concentrations of both were in fraction 20 (arrow), resolved from most other proteins, but some protein also pelleted onto the bottom of the tube with capsid/tegument remnants, which include the major and minor capsid proteins (major capsid protein [MCP], pUL86, 154 kDa; minor capsid protein [mCP], miCP, pUL85, 35 kDa), the tightly associated tegument basic phosphoprotein (BPP, pp150, pUL32, 132 kDa; better resolved in 12% “high-bis” gels [5]), and smaller amounts of several other proteins. In addition to the apparent pUL47/48 complex, four other putative complexes were observed (Fig. 1A, complexes I to IV, protein constituents in ovals).

FIG 1.

HMWP and hmwBP cosediment in glycerol gradients. [35S]methionine-labeled NIEPs and virions (S) were disrupted and separated in 5 to 20% glycerol gradients that were fractionated. Samples of each fraction were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Autoradiographic images of the dried gels are shown with the starting (S) and pelleted (P) material in the left- and right-most lanes. Heated samples from a gradient centrifuged for 36 h (A) and nonheated samples from a gradient centrifuged for 9 h (B) are shown. The arrow indicates the main fraction containing the putative HMWP/hmwBP (pUL47/48) complex; asterisks at the top indicate the main fraction containing heat-aggregated material. Abbreviations indicate positions of the high-molecular-weight protein (HMWP, pUL48), major capsid protein (MCP, pUL86), basic phosphoprotein (BPP, pUL32), amino and carboxyl fragments of cleaved glycoprotein B (gBN and gBC of pUL55), upper (UM, pUL82) and lower (LM, pUL83) matrix proteins, phosphoprotein 28 (pp28, pUL99), and minor capsid protein (mCP, miCP, pUL85). Roman numerals I to IV beneath each image indicate positions of other possible complexes; lettered ovals indicate the putative protein constituents of each. Marker protein weights are indicated to right of the start lane (kDa). The inset panel C shows negatively stained (0.75% aqueous, neutral uranyl formate) material pelleted onto the bottom of the tube and resuspended in PDB with 20% glycerol, following sedimentation separation of disrupted virions as described in Materials and Methods. No intact capsids (∼100 nm in diameter) were observed.

A similarly treated preparation subjected to a shorter time of sedimentation and no sample heating prior to SDS-PAGE showed the same relative distributions of proteins through the gradient, with HMWP and hmwBP cosedimenting in fraction 5 (Fig. 1B, arrow) and capsid/tegument remnants pelleting to the bottom of the tube (Fig. 1C). The four putative complexes observed in Fig. 1A were also detected in this experiment but with the notable difference that complex III yielded at least three additional size-heterogeneous bands in the absence of sample heating (Fig. 1B, ovals a, d, and i). Based on the known masses of virion proteins in the start sample (S), relative mobilities of the proteins in each complex were estimated to be 55 and 28 kDa (complex I), 100 and 65 kDa (II), and 150, 80, and 40 kDa (III). Probable counterparts of these are indicated in Fig. 1A, with the majority of putative complex III proteins appearing to be aggregated at the top of the gel (Fig. 1A and B, positions marked by asterisks). These complexes are discussed below.

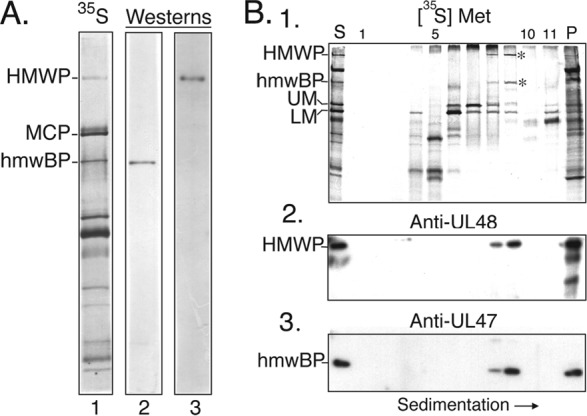

Primary constituents of HMWP/hmwBP complex are pUL47 and pUL48.

To verify the identity of pUL47 and pUL48 as components of the putative complex, Western immunoassays were done. Antibody specificities were validated by probing duplicate samples of [35S]methionine-labeled virion proteins, separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes, with either anti-UL47N′ or anti-UL48N′. An autoradiographic exposure of each membrane prior to the Western assay located the [35S]methionine-labeled HMWP and hmwBP bands, and images prepared following antibody probing showed that a single band corresponding to HMWP was identified by anti-UL48N′ (Fig. 2A, lane 3) and that a single band corresponding to hmwBP was identified by anti-UL47N′ (Fig. 2A, lane 2).

FIG 2.

Anti-UL47N′ and anti-UL48N′ antibodies are specific and identify complex in gradient. (A) A mixture of [35S]methionine-labeled NIEPs and virions was solubilized and subjected to SDS-PAGE (8% polyacrylamide) in duplicate, and proteins were electro-transferred to Immobilon-P membrane. The membrane was cut between samples, and a direct autoradiographic exposure was made (lane 1). Half of the membrane was probed with anti-UL47N′ (lane 2), and the other half was probed with anti-UL48N′ (lane 3). (B) [35S]methionine-labeled HCMV NIEPs and virions (S) were disrupted and separated in a glycerol gradient that was collected into 1-ml fractions. Proteins were concentrated by trichloroacetic acid precipitation, and samples of each fraction were subjected to SDS-PAGE in duplicate gels and electro-transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. Shown here are autoradiographic images of one membrane prior to reaction with antibodies, showing distribution of labeled proteins in the gradient (1). Positions of HMWP and hmwBP are indicated by asterisks. The starting (S) and pelleted (P) material are shown in the left- and right-most lanes, respectively. The same membrane was probed with anti-UL48N′ (2). A duplicate membrane was probed with anti-UL47N′ (3). The 35S signal was blocked in panel A, lanes 2 and 3, and panel B, images 2 and 3. Protein abbreviations shown to the left are as described in the legend of Fig. 1.

These antisera were then used to verify the identity of the two proteins in the HMWP/hmwBP complex (Fig. 1, arrow). Proteins in gradient fractions of disrupted, [35S]methionine-labeled virus particles were probed in Western immunoassays as represented and summarized in Fig. 2A. An autoradiographic image of one membrane before antibody probing showed the gradient position of the HMWP/hmwBP complex (Fig. 2B, membrane 1). Reactivity of anti-UL48N′ with the HMWP band in the complex and of anti-UL47N′ with the hmwBP band in the complex established their identities (Fig. 2B, membranes 2 and 3).

HMWP forms a complex with hmwBP.

The cosedimentation of HMWP and hmwBP suggested that they form a complex, and this was tested by coimmunoprecipitation. Virus particles labeled with [35S]methionine (Fig. 3A, lane 1) were disrupted with PDB and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-UL47N′ or anti-UL48N′, and the recovered proteins were visualized by autoradiography following SDS-PAGE. When anti-UL47N′ was used, HMWP was coimmunoprecipitated along with the antibody target, hmwBP (Fig. 3A, lane 2). When anti-UL48N′ was used, hmwBP was coimmunoprecipitated along with the antibody target, HMWP (Fig. 3A, lane 4). Some major capsid protein (MCP, pUL86) and basic phosphoprotein (BPP, pUL32) were reproducibly found in these immunoprecipitates, most notably with anti-UL48N′ (e.g., Fig. 3A, lane 4, asterisk). None of these proteins was immunoprecipitated by the corresponding preimmune serum (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 5). These data corroborate the interaction of hmwBP with HMWP, as further investigated below.

FIG 3.

HMWP and hmwBP from virions and cells coimmunoprecipitate. (A) [35S]methionine-labeled HCMV NIEPs and virions (S) were disrupted and subjected to immunoprecipitation, followed by SDS-PAGE. An autoradiographic image of the dried gel shows the starting material (lane 1), the proteins immunoprecipitated by anti-UL47N′ antiserum (lane 2) or corresponding preimmunization serum (lane 3), and the proteins immunoprecipitated by anti-UL48N′ (lane 4) or corresponding preimmunization serum (lane 5). (B) A lysate prepared from [35S]methionine-labeled HCMV-infected cells was subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-UL48N′ (lane 1) and corresponding preimmune serum (lane 2) or using anti-UL47N′ (lane 3) and corresponding preimmune serum (lane 4). The immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and an autoradiographic image of the dried gel is shown here. Protein abbreviations shown on the left are as described in the legend of Fig. 1; ∼55 indicates the 55-kDa band in lanes 1 and 3. Asterisks indicate positions of MCP and BPP bands.

Similar results were obtained when the proteins were immunoprecipitated from HCMV-infected cells using anti-UL47N′ or anti-UL48N′. Anti-UL47N′ coimmunoprecipitated HMWP with hmwBP (Fig. 3B, lane 3), and anti-UL48N′ coimmunoprecipitated hmwBP with HMWP (Fig. 3B, lane 1). There was relatively less MCP and BPP in the immunoprecipitates from infected cells than in those from disrupted particles (Fig. 3A and B, asterisks), but two other proteins of undetermined identity (50 to 55 kDa) were detected in the cellular immunoprecipitates.

HMWP/hmwBP complex sediments anomalously in glycerol gradients.

The molar ratio of HMWP to hmwBP was calculated for virions and NIEPs and for the HMWP/hmwBP complex. Independent preparations of virions and NIEPs (5 each) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the CBB-stained proteins were imaged and quantified. Ratios obtained were 1.2 ± 0.2 (virions) and 1.2 ± 0.1 (NIEPs). Four other virion preparations were similarly analyzed following protein staining with SYPRO-R, giving an average HMWP-to-hmwBP ratio of 0.9 ± 0.1. The subunit ratio of the complex was also calculated from sequential measurements of the proteins in a single gel that was first stained with SYPRO-R, then stained with CBB, and finally dried and phosphorimaged. The complex was located by Western immunoassays of three fractionated gradients containing disrupted (i) NIEPS from pUL48/Cys24Ile mutant virus, (ii) [35S]methionine-radiolabeled wild-type virions, and (iii) [35S]methionine-radiolabeled wild-type NIEPs. Samples of the fractions containing the highest concentration of the complex from each source were subjected to SDS-PAGE in one gel and stained with SYPRO-R. A stable HMWP-to-hmwBP ratio of 0.8 ± 0.1 was measured after 24 and 48 h of destaining. Proteins in the same gel stained with CBB gave an HMWP-to-hmwBP ratio of 0.9 ± 0.1, and subsequent phosphorimaging of the dried gel gave an HMWP-to-hmwBP ratio of 1.4 for both radiolabeled complexes (virions and NIEPs), correcting for the difference of 42 methionines in HMWP versus 17 in hmwBP. Thus, all three determinations gave values approximating 1:1 for the subunit ratio of the pUL47/48 complex.

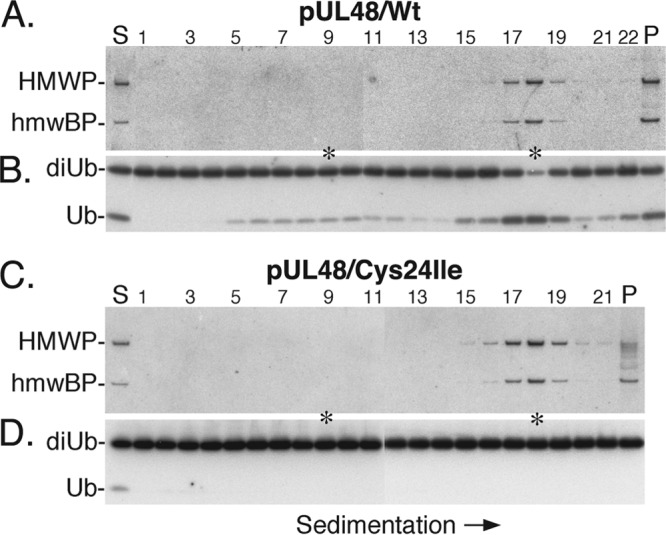

To determine whether the ∼1:1 subunit ratio of the complex reflects a simple heterodimer or occurs in a higher-order structure, we compared its sedimentation with that of marker proteins in a parallel gradient. A third gradient was overlaid with an equal amount of the same virion preparation but with 0.3% SDS added to the particle disruption buffer. Western immunoassays done using a mixture of anti-UL47N′ and anti-UL48N′ located the HMWP/hmwBP complex, and CBB staining located the marker proteins in the respective gradients (Fig. 4A, −SDS). The complex was most abundant in fraction 13 (Fig. 4A, −SDS, arrow), which interpolates to ∼183 kDa, relative to the marker proteins. This size is only half that predicted for a heterodimer (i.e., the 253-kDa HMWP plus the 110-kDa hmwBP yields 363 kDa) and lower even than expected for monomeric HMWP, indicating that the complex sediments anomalously.

FIG 4.

Evidence that HMWP/hmwBP complex is elongated. (A) HCMV NIEPs and virions were disrupted in PDB without (−SDS) or with (+SDS) 0.3% SDS, separated by rate-velocity sedimentation, and fractionated. After trichloroacetic acid precipitation and SDS-PAGE, Western immunoassays using a mixture of anti-UL47N′ and anti-UL48N′ were done to locate the HMWP and hmwBP. Shown here are phosphorimages of the resulting blots. A sample of the starting material (S) was in the left lane, and numbers at the top indicate masses of the marker proteins ovalbumin (43 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and catalase (232 kDa) that were separated in a parallel gradient, lacking DTT, and whose positions were detected by fractionating the gradient, subjecting the proteins to SDS-PAGE, and visualizing them with CBB. The arrow indicates the position of pUL47/48 complex (−SDS); asterisks indicate positions of HMWP and hmwBP (+SDS). (B) [35S]methionine-labeled NIEPs and virions were disrupted and subjected to gel filtration chromatography. Samples of the gradient fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and an autoradiogram of the resulting dried gel is shown. A portion of the starting material (S) is shown in the left lane. Lettered boxes indicate the fractions having the highest concentrations of specific proteins; boxes for proteins having similar elution patterns were given the same letter (i.e., a to e). Masses (in kDa), shown at the top, were estimated from the elution volumes of marker proteins subjected to the same chromatography but using buffers without DTT. Protein abbreviations to the left are as described in the legend of Fig. 1.

Addition of SDS to the particle disruption buffer resulted in a marked shift in the sedimentation of hmwBP to a position (∼90 kDa) more closely approximating its predicted 110-kDa monomer size (Fig. 4A, +SDS). Sedimentation of HMWP was less affected by SDS, moving just slower than the complex (Fig. 4A, +SDS, asterisk to right of the 158-kDa marker). This altered sedimentation pattern is consistent with disruption of SDS-sensitive intermolecular interactions that hold the HMWP/hmwBP complex together under less stringent conditions.

HMWP/hmwBP complex appears larger than a heterodimer when analyzed by chromatography.

Size estimates of the HMWP/hmwBP complex were also made by gel filtration chromatography using Sephacryl S-300 HR, which resolves in the range of 40 kDa to 1.5 MDa. [35S]methionine-radiolabeled virus particles were disrupted in PDB and subjected to chromatography, and samples of the resulting column fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE. An autoradiogram prepared from the dried gel revealed at least three apparent complexes among the eluted proteins: (i) one containing MCP/BPP/LM/mCP (where LM is lower matrix protein) (Fig. 4B, boxes a), thought to represent virus capsid (e.g., MCP and mCP)-tegument (e.g., BPP and LM) structures, eluted in or close to the void volume of the column; (ii) one containing the pUL47/48 complex (Fig. 4B, boxes b) eluted close to the blue dextran marker; and (iii) one containing the amino and carboxyl fragments of cleaved glycoprotein B (gBN and gBC, respectively) (Fig. 4B, boxes 3) eluted between the 669-kDa marker and blue dextran, with an estimated size of ∼1 MDa under these conditions.

Because the complex appeared much smaller when measured by sedimentation, we tested its chromatographic behavior after first subjecting it to rate-velocity sedimentation. No change was evident in the chromatography of this material, which again eluted in the same fractions as blue dextran. Thus, the same material estimated by sedimentation to be ≈170 to 195 kDa, much smaller than a 363-kDa HMWP/hmwBP dimer, behaved as though it were three times larger than a heterodimer (i.e., ∼0.9 to 1.1 MDa) during gel filtration chromatography.

Amino one-third of HMWP interacts with carboxyl one-third of hmwBP.

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were used to identify the region of HMWP to which hmwBP binds. Large overlapping fragments of HMWP, representing its amino (aa 1 to 1200, aa 1 to 754, and aa 1 to 396) and carboxyl (aa 1108 to 2241) portions, were biosynthetically radiolabeled with [35S]methionine in vitro, combined with similarly prepared hmwBP, and then immunoprecipitated using anti-UL47C′ or anti-UL48N′. The pUL47C′ antiserum did not precipitate the HMWP fragments in the absence of hmwBP (data not shown), nor did it coimmunoprecipitate the carboxyl HMWP reporter fragment (aa 1108 to 2241) in combination with hmwBP (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 4) even though this fragment was in excess in the starting mixture (data not shown). In contrast, HMWP aa 1 to 1200 did coimmunoprecipitate with hmwBP (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 1). A smaller fragment representing the amino one-third of HMWP (i.e., aa 1 to 754) also coimmunoprecipitated with hmwBP (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 2), but an even smaller fragment (aa 1 to 396) (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 3) did not. Consistent with these results, an HMWP truncation mutant (aa 322 to 754) (Fig. 5A, candidate, and B, lane 5) missing most of the same sequence (i.e., aa 1 to 321) did coimmunoprecipitate with the full-length hmwBP. These data indicate that amino acid sequence at residues 322 to 754 within the amino one-third of HMWP contains an hmwBP binding domain.

A similar approach was used to localize the region of hmwBP that binds HMWP. The fragment of HMWP containing the hmwBP binding region (aa 322 to 754) was used as the reporter and coimmunoprecipitated a fragment representing the carboxyl one-third of pUL47 (aa 693 to 982) (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 7) but not the fragment representing its amino two-thirds (aa 1 to 654) (Fig. 5A, and B, lane 6). Control reactions revealed little (with anti-UL47N′) or no (with anti-UL47C′) cross-reaction between the test antisera and the pUL48 reporter fragment (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that a sequence in the amino one-third of HMWP (aa 322 to 754) interacts with a sequence in the carboxyl one-third of hmwBP (aa 693 to 982).

The hmwBP self-interacts head to tail.

Given reports of self-interactions for both the HMWP (20, 61, 62) and hmwBP (63, 64) counterparts, we applied the fragment coimmunoprecipitation approach described above to test for self-interaction of hmwBP and HMWP.

Although multiple attempts to detect interaction between the amino (aa 1 to 1200) and carboxyl (aa 1108 to 2241) halves of HMWP were inconclusive, positive results were obtained with pUL47. We found that overlapping fragments representing both the amino 84% (aa 1 to 829) and carboxyl 30% (aa 693 to 982) of hmwBP coimmunoprecipitated with full-length pUL47 (Fig. 5, lanes 8 and 9, respectively), whereas neither fragment was immunoprecipitated when tested alone with the respective antisera (data not shown). This result could be explained by the interactive domain(s) lying within the amino acid sequence common to the two fragments (i.e., aa 693 to 829) or to the presence of two separate interactive domains, one in the amino fragment and one in the carboxyl fragment.

To discriminate between these possibilities, the experiment was repeated using nonoverlapping amino (aa 1 to 654) and carboxyl (aa 693 to 982) fragments. The carboxyl reporter fragment interacted with full-length hmwBP (Fig. 5, lane 10) as observed before (Fig. 5, lane 9), with the overlapping fragment (Fig. 5, lane 11), and with the nonoverlapping amino fragment (Fig. 5, lane 12). Interaction of the amino fragment of aa 1 to 654 with the nonoverlapping carboxyl reporter fragment of aa 693 to 982 indicates that two regions of hmwBP take part in its self-interaction.

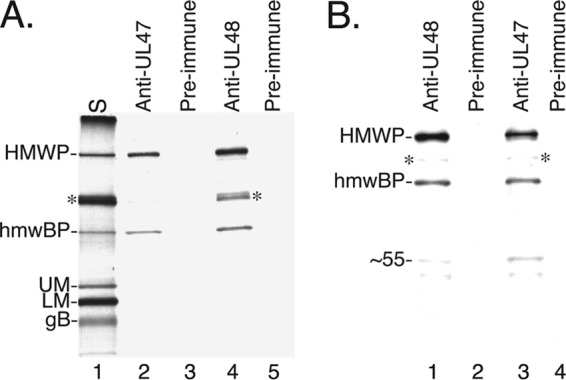

The HMWP/hmwBP complex has deubiquitylating activity.

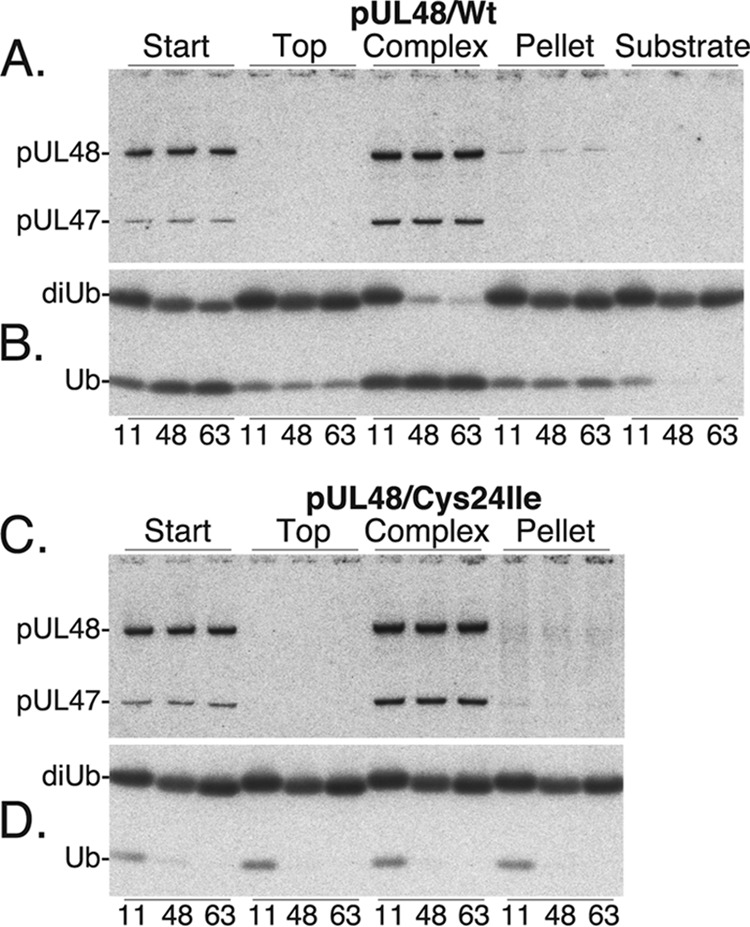

The full-length HMWP present in virus particles has deubiquitylating (DUB) activity (43). To determine whether this activity is also exhibited by the HMWP/hmwBP complex, we separated the complex from other virion proteins by gradient sedimentation and fractionation and determined the distribution of hmwBP, HMWP, and DUB activity in the resulting gradient fractions, all as described in Materials and Methods. Virions from a mutant encoding an inactive HMWP DUB (pUL48/Cys24Ile) (44) were analyzed in parallel for comparison.

The distribution of hmwBP and HMWP in the gradients was determined by Western immunoassay, using a mixture of anti-UL47N′ and anti-UL48N′. Both proteins were present at the position of the HMWP/hmwBP complex (Fig. 6A and C, asterisk, fraction 18), with some in flanking fractions and some in the pellet (P). Their distributions in the gradient were essentially the same, whether from virus with wild-type or Cys24Ile mutant HMWP (Fig. 6A and C, respectively), and their highest concentrations were in fraction 18, with smaller amounts in adjacent fractions. Some variation was observed from experiment to experiment in the relative amount of HMWP and hmwBP that sedimented as a complex versus pellets (compare Fig. 6A and C). This is due to experimental variation in the extent to which the starting virion pellet is disrupted prior to sedimentation and the resulting final pellet is recovered and dispersed following sedimentation.

FIG 6.

HMWP/hmwBP complex has deubiquitylating activity. Samples from fractions of gradients containing disrupted virions were tested for the presence of hmwBP (pUL47), HMWP (pUL48), and DUB activity by Western immunoassays. Shown here are phosphorimages prepared from the resulting membranes. (A) Membrane probed with a mixture of anti-UL47N′ and anti-UL48N′ to identify the location of the HMWP and hmwBP in the gradient containing wild-type (Wt) HMWP. The same membrane was used for the experiment shown in panel B but was probed and imaged a second time. (B) The membrane was probed with anti-ubiquitin and imaged and then used again for the experiment shown in panel A. (C and D) Membranes were prepared and processed in parallel with those shown in panels A and B but using fractions from the gradient containing disrupted pUL48/Cys24Ile mutant virions instead of the wild type. The positions of HMWP, hmwBP, substrate diubiquitin (di-Ub), product mono-ubiquitin (Ub), and regions of the top and complex fractions showing strongest DUB activity (asterisks) are indicated. Start (S), pellet (P), and gradient fraction numbers are shown at the top of panels A and C.

Samples of the same gradient fractions were then surveyed for DUB activity by Western immunoassay, as described in Materials and Methods. K63-linked di-Ub substrate was cleaved to mono-Ub in all fractions containing HMWP, with greater cleavage in fractions containing the most HMWP (Fig. 6B, fraction 18 and P). There was also some substrate cleavage in fractions 5 to 14, containing smaller, slower-sedimenting material (Fig. 6B), but only in the gradient containing active HMWP DUB (Fig. 6B). We interpret the absence of corresponding DUB activity in these fractions from the pUL48/C24I mutant (Fig. 6D) to indicate that it originates from pUL48 and is therefore inactivated by the mutation. Mono-Ub detected in the start (S) and top few fractions of the gradient containing inactive pUL48 (Fig. 6D) was present in the virion preparation and not due to substrate cleavage (data not shown).

Fresh samples of the start (S), top (fraction 9), complex (fraction 18), and the pellet (P) from each gradient were compared for DUB substrate specificity and specific activity by reaction with K11-, K48-, and K63-linked di-Ub for 2 h at 37°C. Phosphorimaging of Western immunoassays was done to quantify substrate cleavage (amount of mono-Ub product) and the amount of HMWP in each reaction (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

HMWP/hmwBP complex cleaves K11-, K48-, and K63-linked ubiquitin. Equal samples of the starting material (S), top (fraction 9), complex (fraction 18), and pellet (P) fractions from the gradients shown in Fig. 6A (wild-type HMWP) and C (pUL48/Cys24Ile) were tested for activity against K11-, K48-, and K63-linked diubiquitin substrates. Shown here are phosphorimages of Western immunoassays done to determine the relative amount of HMWP/hmwBP complex (A) and DUB activity (B) present in samples from the gradient with wild-type pUL48. Corresponding samples from the gradient with mutant pUL48/Cys24Ile were similarly tested for HMWP/hmwBP complex (C) and for DUB activity (D).

Less than 7% variation was found in the amount of HMWP within the start and complex reaction sets (Fig. 7A), enabling substrate specificity comparisons of the two. Our calculations indicated that within the start and complex reaction sets, cleavage efficiencies of the K48- and K63-linked substrates were comparable, whereas cleavage of the K11 substrate was less efficient. The normalized ratios were 1.0:1.1:0.4 for the start reactions and 1:1:0.7 for the complex reactions (K48/K63/K11).

The relative specific activities of the start and complex fractions with K48 and K63 di-Ub substrates were also calculated. The amounts of HMWP in the K48 and K63 complex reactions were averaged and determined to be 2.4-fold more than in the corresponding start reactions (Fig. 7A). The amount of mono-Ub product was similarly compared and found to be 1.6-fold more in the complex reactions (Fig. 7B), or 67% of the amount predicted if the start and complex specific activities were the same.

Similar calculations of substrate specificity and specific activity were not possible for the top and pellet fractions since the amounts of HMWP and mono-Ub in those reaction sets were below the level of confidence for the assay system.

No DUB activity was detected against any of the substrates tested with corresponding fractions from the gradient containing mutant HMWP (Fig. 7C and D). The K11- and K48-linked di-Ub substrates contained small amounts of mono-Ub (∼ 9% and 0.7%, respectively, by Western immunoassay), which is most evident in the K11 substrate (Fig. 7B, substrate) and in each of the K11 reactions represented in Fig. 7D. Using the same assay format, we also determined that the DUB activity in the HMWP/hmwBP complex (fraction 18) failed to cleave head-to-tail (N′ to C′)-linked Ub-SUMO and Ub-Ub substrates (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We show here that the HCMV high-molecular-weight-protein (HMWP, pUL48) forms a complex with the HMWP-binding protein (hmwBP, pUL47) (Fig. 1 and 2). The complex, as recovered from virions, has a subunit ratio approximating 1:1, has hydrodynamic properties consistent with it being rod shaped rather than globular, and retains the deubiquitylating activity of HMWP. Experiments to identify the region of each subunit involved in intermolecular binding indicate that the amino one-third of HMWP interacts with the carboxyl one-third of hmwBP and that hmwBP also participates in a head-to-tail self-interaction.

Our conclusion that the HMWP and hmwBP form a complex is based on three lines of evidence: (i) they comigrate during sedimentation ultracentrifugation and gel filtration chromatography (Fig. 1 and 4), (ii) each protein coimmunoprecipitates with its partner subunit (Fig. 3), and (iii) specific fragments of each contain binding sites for the other (Fig. 5). These findings corroborate and extend earlier reports that HCMV hmwBP and HMWP interact (19, 31) and provide the first demonstration for any herpesvirus that this complex can be released from the virion, identified, and recovered for further study in vitro.

Subunit composition and shape of complex.

A molar ratio approximating 1:1 was determined for hmwBP to HMWP in the complex, calculated from measurements of the proteins stained with SYPRO-R or CBB or radiolabeled with [35S]methionine, and was similar in virus particles as determined here and before (5). In contrast to consistent results for stoichiometry, size estimates of the complex differed reproducibly, depending on the method used. Rate-velocity centrifugation indicated a size of 183 kDa (Fig. 4A), which is smaller than the 253-kDa HMWP subunit alone, whereas gel filtration chromatography indicated a size of ∼1 MDa (Fig. 4B), i.e., larger than a hypothetical 726-kDa α2/β2 tetramer.

These differing size estimates were reconciled by using the method of Siegel and Monty to first determine a Stoke's radius (Rs) and sedimentation coefficient (S) and from them deriving an approximate molecular mass (65). Our data give an Rs of 9.1 nm, an S of 8.7, and 334 kDa as a projected mass for the HMWP/hmwBP complex, consistent with a 363-kDa heterodimer. An approximate maximum sedimentation coefficient, Smax, can be derived from the theoretical molecular weight of the dimer (66). The ratio between Smax and S can then be taken to give an idea of the shape of the protein complex. For the HMWP/hmwBP complex we calculate a theoretical ratio of 2.1, indicating a highly elongated structure, as seen in proteins such as tropomyosin and fibrinogen (67). Moreover, when parts of the carboxyl portion of HMWP (e.g., aa 1160 to 1584) were computationally modeled using Phyre2 (68), the predicted structure was an elongated alpha helix, again with similarity to tropomyosin and fibrinogen. Taking these results together, we interpret the discrepancy between our sedimentation and chromatography data as indicating that the HMWP/hmwBP complex has a rod-like rather than globular structure.

Domains mediating HMWP and hmwBP interactions.

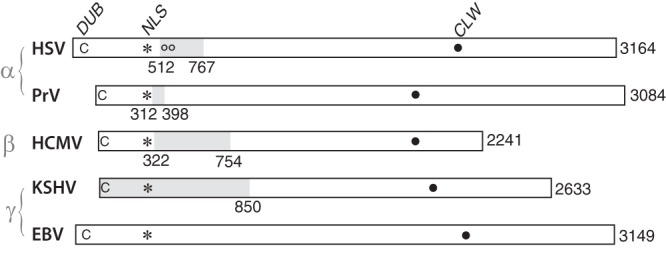

The counterpart proteins of alphaherpesviruses HSV and pseudorabies virus (PRV) (pUL36 and pUL37) and gammaherpesvirus Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (ORF64 and ORF63) also interact, as shown using coimmunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid assays (62, 64, 69–71). For HSV, the regions of pUL36 and pUL37 that mediate this interaction have been identified near the amino end of pUL36 and the carboxyl end of pUL37 (63, 64). Moreover, specific amino acids implicated as critical to this interaction have been identified by Ala-scanning mutagenesis in both pUL36 (72) and pUL37 (73). In KSHV the interactive portion of ORF64 has also been localized to its amino end (62). Our findings reported here are the first to identify counterpart domains in a betaherpesvirus (i.e., in HCMV, HMWP and hmwBP) that mediate corresponding interactions. As shown in Fig. 8, when these proteins are aligned in relation to the conserved nuclear localization sequence (NLS), the interactive domain we identify here for pUL48 is positionally consistent with the domains recognized in other HMWP counterparts.

FIG 8.

HMWP/hmwBP interactive region conserved. Alignment of HMWP (e.g., HCMV pUL48) homologs from representative alpha-, beta-, and gammaherpesviruses showing regions of interaction (gray shading) with corresponding hmwBP (e.g., HCMV pUL47) homologs. Numbers indicate amino acids at amino and carboxyl ends of the interactive domain and at the carboxyl end of the full-length ORF. Other abbreviations and symbols represent a conserved catalytic cysteine (C) of each deubiquitylase (DUB), conserved nuclear localization sequence (asterisk, NLS), amino acid substitutions 593 and 596 that interfere with the HSV pUL36/37 interaction (oo), and an interesting point-of-reference conserved leucine, tryptophan sequence (CLW, {xP]/[Px}x4LWx4P).

In addition to binding HMWP, hmwBP was also found to self-interact head to tail, as has been reported for its HSV counterpart (63, 64) and shown there to be mediated by amino acids 1 to 300 and 568 to 1123 (63). Self-interaction of HMWP, on the other hand, was not reproducibly detected in our assays, nor has it been reported for the pUL36 counterpart of HSV or PRV. Interestingly, and perhaps representing a difference between the alpha- and betaherpesvirus versus gammaherpesvirus HMWP proteins, self-interaction has been reported for these Epstein-Barr virus (EBV; ORF BPLF1) and KSHV (ORF 64) homologs (20, 62). Large and small changes to a protein have the potential to disrupt structure and function. Nevertheless, our mapping data for the HMWP-hmwBP counterparts of HCMV, considered together with data obtained using other herpesviruses and different assay methods, reinforce the similar conclusions.

Our finding that HMWP and hmwBP are present in a ∼1:1 ratio in the HMWP/hmwBP complex and in virions is consistent with a single primary interaction between the amino end of HMWP and the carboxyl end of hmwBP but does not account for the prediction that hmwBP is competent for an additional head-to-tail self-interaction through its amino end The observed stoichiometry suggests that if this interaction occurs in virus-infected cells, the resulting product is not favored for incorporation into virions. A restricting conformational change in the small subunit resulting from its interaction with the large subunit or a competing interaction with a different protein could help ensure this outcome. Our observation that few, if any, other proteins specifically cosediment with the HMWP/hmwBP complex indicates that interaction of the HMWP and hmwBP subunits is more resistant to the combination of denaturants used (1% NP-40, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 M NaCl) than are interactions of the complex with capsid proteins and with other tegument and envelope constituents.

It is curious that HSV pUL36 and pUL37, which are present in virions in the same ratio to each other (∼1:1) and to MCP (1:5) as are pUL47 and pUL48 in virions and NIEPs of HCMV (reference 5 and the present study), dissociate under similar denaturing conditions (1% Triton X-100, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM DTT), with pUL37 being removed and pUL36 remaining tightly associated with the capsid (11). Considering that these HSV proteins interact with each other through regions positionally similar to their PRV and HCMV counterparts (see below) (Fig. 8), this finding suggests a difference in capsid binding affinities between the HMWP homologs, HSV pUL36 and HCMV pUL48. HSV pUL36 differs in at least two other possibly related ways from HCMV pUL48: it is ∼83 kDa heavier, and it is highly phosphorylated (48, 74). Tight binding to the capsid is a hallmark of the highly phosphorylated 112-kDa HCMV basic phosphoprotein (BPP, pp150, pUL32) (15, 32, 33, 60), which functions to stabilize the nucleocapsid (34) but is without an HSV homolog. More information is needed to resolve whether functions requiring both HMWP and BPP in HCMV may be fulfilled by pUL36 alone or in combination with a different protein in HSV.

Other complexes identified following sedimentation of disrupted virions.

In addition to the HMWP/hmwBP complex, other apparent complexes were detected following sedimentation of disrupted, [35S]methionine-radiolabeled virions. These were designated complexes I to IV (Fig. 1). Among their protein constituents, only two were unambiguously identified: complex II band e is the lower matrix protein (LM, pp65, pUL83) and complex IV band f is the carboxyl half of cleaved gB (gBC, pUL55). Complex IV band b is likely to be the more highly glycosylated amino half of gB (gBN) cosedimenting with gBC. Some lower matrix protein appears to sediment with complex IV and may contribute to its large size.

Complex III is of particular interest as it appears to be comprised of at least four proteins (a, d, g, and i), all of which show size heterogeneity and at least three of which (a, d, and i) aggregate when heated—properties consistent with hydrophobic glycoproteins such as the G-protein-coupled receptor (GCR) proteins (pUS27, pUS28, and pUL33) (75, 76) and envelope glycoproteins gM and gN (77). Some upper matrix protein (UM, pp71, pUL82) appears to cosediment with these proteins as part of the complex. The identity of these proteins remains speculative but is of interest in the context of establishing tegument/glycoprotein interaction networks and from the perspective of identifying glycoprotein complexes that may have application in developing antivirals (e.g., vaccines, receptor blockers, and envelopment inhibitors).

DUB activity of HMWP/hmwBP complex.

Our assays for deubiquitylating (DUB) activity following gradient fractionation of disrupted HCMV virions showed (i) that the DUB of the HMWP/hmwBP complex was comparable in specificity and activity to that in disrupted but unfractionated virus particles (i.e., start fraction) and (ii) that all DUB activity detected in the gradient derived from HMWP (i.e., complete lack of activity pUL48/Cys24Ile mutant) (Fig. 6D). The specificity of some DUBs for particular linkages can be predictive of function. A specificity for K48-linked ubiquitin oligomers suggests a role in modulating degradation by the proteasome; specificity for K63-linked oligomers, which decorate multivesicular body (MVB) cargoes, is suggestive of an involvement in the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) pathway; and specificity for K11-linked ubiquitin oligomers has been correlated with an involvement in cell cycle regulation. The HMWP/hmwBP complex was active against all of these linkages in our in vitro assays, indicating a broad reactivity against isopeptide-linked ubiquitin, as studied previously by others (45, 47), and inactive against the two non-isopeptide-linked substrates tested, head-to-tail-linked diubiquitin and ubiquitin-SUMO (Fig. 7 and data not shown). The broad reactivity of this DUB may enable it to remove mono- or poly-Ub by cleaving between ubiquitin and target protein backbones, including that of the DUB itself (78, 79; also our unpublished findings with HCMV pUL48) although few DUBs with this ability have been described (80).

During infection, in contrast to in vitro assays using purified or enriched-for proteins, the HMWP DUB is likely to gain substrate specificity by interactions with other proteins and through protein trafficking and compartmentalization. Although interaction with hmwBP may not influence the substrate specificity of the HMWP DUB toward small di-Ub substrates, it or other viral or cellular proteins could lend specificity toward larger or otherwise different substrate proteins in virus-infected cells. Trafficking and intracellular localization of the HMWP DUB may also be important contributing factors in achieving substrate specificity. Evidence for interactions of the HSV, EBV, and KSHV HMWP counterparts with both cellular and viral proteins has been reported. For example, the cellular protein Tsg101 was found to be a target during HSV infection, which may have implications for virus interactions with the ESCRT machinery (79). In EBV, TRAF6 and PCNA have been identified as substrates (81, 82); both are involved in pathways responsible for DNA repair and replication. And in another study the KSHV ORF64 homolog has been found to suppress RIG-I-mediated interferon signaling (83). More recently, the structure of the amino half of the pseudorabies virus hmwBP homolog, pUL37, was solved and found to resemble proteins in the multisubunit tethering complex, suggesting that it may function in membrane fusion (84) and perhaps help target the HMWP DUB to specific substrates.

The rod-shaped structure of the complex, interpreted from sedimentation and chromatography studies, is consistent with interpretations drawn from electron microscopy (12, 32) and the suggestion that the large subunit of this complex (HMWP) may serve as a scaffold to guide organization of other tegument proteins during virus formation (17) and as a snare to facilitate movement of the deenveloped virus particle toward the nucleus during infection (40). Our demonstration here that HCMV tegument proteins pUL47 and pUL48 form a discrete complex that can be recovered from disrupted HCMV particles gives new information and insight into its structure, composition, and interactions. Stability of the complex under the conditions of disruption indicates a stronger association of the subunits with themselves than of the complex with the capsid or other virion proteins. The ability to separate the complex from the capsid is expected to enable its further physical and biochemical analysis in isolation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven Foung and Peggy Bradford for human monoclonal antibody X2-16 to HMWP (pUL48) used during pilot experiments, Min Li for help with the gel filtration experiment shown in Fig. 4B, Cynthia Wolberger and colleagues Anthony DiBello and Xiangbin Zhang for generously providing DUB substrates, including the K11-, K48-, and K63-linked ubiquitin dimers used in the experiments shown in Fig. 6 and 7.

M.-E.H. was a student in the Pharmacology Graduate Program and aided by USPHS grant T32 GM07626. J.A.T. was aided by a postdoctoral award from USPHS grant T32 CA009243. Portions of this work were aided by USPH research grants AI13718 and AI082246 to W.G.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Roizman B, Furlong D. 1974. The replication of herpesviruses, p 229–403 In Fraenkel-Conrat H, Wagner RR. (ed), Comprehensive virology. Plenum, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spear PG, Roizman B. 1972. Proteins specified by herpes simplex virus. V. Purification and structural proteins of the herpesvirion. J. Virol. 9:143–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson W, Roizman B. 1972. Proteins specified by herpes simplex virus. VIII. characterization and composition of multiple capsid forms of subtypes 1 and 2. J. Virol. 10:1044–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newcomb WW, Trus BL, Booy FP, Steven AC, Wall JS, Brown JC. 1993. Structure of the herpes simplex virus capsid: molecular composition of the pentons and the triplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 232:499–511. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irmiere A, Gibson W. 1983. Isolation and characterization of a noninfectious virion-like particle released from cells infected with human strains of cytomegalovirus. Virology 130:118–133. 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90122-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldick CJ, Shenk T. 1996. Proteins associated with purified human cytomegalovirus particles. J. Virol. 70:6097–6105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rixon FJ, Addison C, McLauchlan J. 1992. Assembly of enveloped tegument structures (L particles) can occur independently of virion maturation in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 73:277–284. 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trus BL, Heymann JB, Nealon K, Cheng N, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Kedes DH, Steven AC. 2001. Capsid structure of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, a gammaherpesvirus, compared to those of an alphaherpesvirus, herpes simplex virus type 1, and a betaherpesvirus, cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 75:2879–2890. 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2879-2890.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatman JD, Preston VG, Nicholson P, Elliott RM, Rixon FJ. 1994. Assembly of herpes simplex virus type 1 capsids using a panel of recombinant baculoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1101–1113. 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomsen DR, Roof LL, Homa FL. 1994. Assembly of herpes simplex virus (HSV) intermediate capsids in insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses expressing HSV capsid proteins. J. Virol. 68:2442–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newcomb WW, Jones LM, Dee A, Chaudhry F, Brown JC. 2012. Role of a reducing environment in disassembly of the herpesvirus tegument. Virology 431:71–79. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen DH, Jiang H, Lee M, Liu F, Zhou ZH. 1999. Three-dimensional visualization of tegument/capsid interactions in the intact human cytomegalovirus. Virology 260:10–16. 10.1006/viro.1999.9791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo H, Shen S, Wang L, Deng H. 2010. Role of tegument proteins in herpesvirus assembly and egress. Protein Cell 1:987–998. 10.1007/s13238-010-0120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou ZH, Chen DH, Jakana J, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. 1999. Visualization of tegument-capsid interactions and DNA in intact herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J. Virol. 73:3210–3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baxter MK, Gibson W. 2001. Cytomegalovirus basic phosphoprotein (pUL32) binds to capsids in vitro through its amino one-third. J. Virol. 75:6865–6873. 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6865-6873.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JI-H, Luxton GW, Smith GA. 2006. Identification of an essential domain in the herpesvirus VP1/2 tegument protein: the carboxy terminus directs incorporation into capsid assemblons. J. Virol. 80:12086–12094. 10.1128/JVI.01184-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardone G, Newcomb WW, Cheng N, Wingfield PT, Trus BL, Brown JC, Steven AC. 2012. The UL36 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus 1 has a composite binding site at the capsid vertices. J. Virol. 86:4058–4064. 10.1128/JVI.00012-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coller KE, Lee JI, Ueda A, Smith GB. 2007. The capsid and tegument of the alphaherpesviruses are linked by an interaction between the UL25 and VP1/2 proteins. J. Virol. 81:11790–11797. 10.1128/JVI.01113-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.To A, Bai Y, Shen A, Gong H, Umamoto S, Lu S, Liu F. 2011. Yeast two hybrid analyses reveal novel binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus-encoded virion proteins. PLoS One 6:e17796. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calderwood M a, Venkatesan K, Xing L, Chase MR, Vazquez A, Holthaus AM, Ewence AE, Li N, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Hill DE, Vidal M, Kieff E, Johannsen E. 2007. Epstein-Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7606–7611. 10.1073/pnas.0702332104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H. 2009. Herpesvirus assembly: an update. Virus Res. 143:222–234. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalejta RF. 2013. Pre-immediate early tegument protein functions, p 141–151 In Reddehase MJ, Lemmermann NAW. (ed), Cytomegaloviruses, from molecular pathogenesis to intervention. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tandon R, Mocarski ES. 2012. Viral and host control of cytomegalovirus maturation. Trends Microbiol. 20:392–401. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfstein A, Nagel C-H, Radtke K, Döhner K, Allan VJ, Sodeik B. 2006. The inner tegument promotes herpes simplex virus capsid motility along microtubules in vitro. Traffic 7:227–237. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson DC, Baines JD. 2011. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:382–394. 10.1038/nrmicro2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mettenleiter TC. 2004. Budding events in herpesvirus morphogenesis. Virus Res. 106:167–180. 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa-Goto K, Tanaka K, Gibson W, Moriisihi E, Miura Y, Kurata T, Irie S, Sata T. 2003. Microtubule network facilitates nuclear targeting of human cytomegalovirus capsid. J. Virol. 77:8541–8547. 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8541-8547.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalejta RF. 2008. Fuctions of human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins prior to immediate early gene expression, p 101–115 In Shenk T, Stinski MF. (ed), Human cytomegalovirus. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyman MG, Enquist LW. 2009. Herpesvirus interactions with the host cytoskeleton. J. Virol. 83:2058–2066. 10.1128/JVI.01718-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Britt B. 2007. Maturation and egress, p 311–323 In Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K. (ed), Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bechtel JT, Shenk T. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus UL47 tegument protein functions after entry and before immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 76:1043–1050. 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1043-1050.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai X, Yu X, Gong H, Jiang X, Abenes G, Liu H, Shivakoti S, Britt WJ, Zhu H, Liu F, Zhou ZH. 2013. The smallest capsid protein mediates binding of the essential tegument protein pp150 to stabilize DNA-containing capsids in human cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003525. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trus BL, Gibson W, Cheng N, Steven AC. 1999. Capsid structure of simian cytomegalovirus from cryoelectron microscopy: evidence for tegument attachment sites. J. Virol. 73:2181–2192 (Erratum, 73:4530.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AuCoin DP, Smith GB, Meiering CD, Mocarski ES. 2006. Betaherpesvirus-conserved cytomegalovirus tegument protein ppUL32 (pp150) controls cytoplasmic events during virion maturation. J. Virol. 80:8199–8210. 10.1128/JVI.00457-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tandon R, Mocarski ES. 2011. Cytomegalovirus pUL96 is critical for the stability of pp150-associated nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 85:7129–7141. 10.1128/JVI.02549-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradshaw P, Duran-Guarino R, Perkins S, Rowe J, Young L, Foung S. 1994. Location of antigenic sites on human cytomegalovirus virion structural proteins encoded by UL48 and UL56. Virology 205:321–328. 10.1006/viro.1994.1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bucks MA, O'Regan KJ, Murphy MA, Wills JW, Courtney RJ. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument proteins VP1/2 and UL37 are associated with intranuclear capsids. Virology 361:316–324. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knipe DM, Ruyechan WT, Roizman B. 1979. Molecular genetics of herpes simplex virus. III. Fine mapping of a genetic locus determining resistance to phosphonoacetate by two methods of marker transfer. J. Virol. 29:698–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batterson W, Furlong D, Roizman B. 1983. Molecular genetics of herpes simplex virus. VIII. Further characterization of a temperature-sensitive mutant defective in release of viral DNA and in other stages of viral reproductive cycle. J. Virol. 45:397–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sodeik B, Ebersold MW, Helenius A. 1997. Microtubule-mediated transport of incoming herpes simplex virus 1 capsids to the nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 136:1007–1021. 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts APE, Abaitua F, O'Hare P, McNab D, Rixon FJ, Pasdeloup D. 2009. Differing roles of inner tegument proteins pUL36 and pUL37 during entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 83:105–116. 10.1128/JVI.01032-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desai P. 2000. A null mutation in the UL36 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 results in the accumulation of unenveloped DNA-filled capsids in the cytoplasm of infected cells. J. Virol. 74:11608–11618. 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11608-11618.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Granzow H, Mettenleiter TC. 2004. Essential function of the pseudorabies virus UL36 gene product is independent of its interaction with the UL37 protein. J. Virol. 78:11879–11889. 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11879-11889.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Loveland AN, Kattenhorn LM, Ploegh HL, Gibson W. 2006. High-molecular-weight protein (pUL48) of human cytomegalovirus is a competent deubiquitinating protease: mutant viruses altered in its active-site cysteine or histidine are viable. J. Virol. 80:6003–6012. 10.1128/JVI.00401-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kattenhorn LM, Korbel GA, Kessler BM, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. 2005. A deubiquitinating enzyme encoded by HSV-1 belongs to a family of cysteine proteases that is conserved across the family Herpesviridae. Mol. Cell 19:547–557. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlieker C, Korbel GA, Kattenhorn LM, Ploegh HL. 2005. A deubiquitinating activity is conserved in the large tegument protein of the Herpesviridae. J. Virol. 79:15582–15585. 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15582-15585.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim ET, Oh SE, Lee Y-O, Gibson W, Ahn J-H. 2009. Cleavage specificity of the UL48 deubiquitinating protease activity of human cytomegalovirus and the growth of an active-site mutant virus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 83:12046–12056. 10.1128/JVI.00411-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roby C, Gibson W. 1986. Characterization of phosphoproteins and protein kinase activity of virions, noninfectious enveloped particles, and dense bodies of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 59:714–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harmon M-E, Gibson W. 1996. High molecular weight virion protein of human cytomegalovirus forms complex with product of adjacent open reading frame, abstr W35-4, p 144 Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Virology, London, Ontario, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibson W. 1981. Structural and nonstructural proteins of strain Colburn cytomegalovirus. Virology 111:516–537. 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90354-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chee MS, Bankier AT, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown CM, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison CA, Kouzarides T, Martignetti JA, Preddie E, Satchwell SC, Tomlinson P, Weston KM, Barrell BG. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borst E, Messerle M. 2000. Development of a cytomegalovirus vector for somatic gene therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 25(Suppl 2):S80–S82. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muyrers JP, Zhang Y, Benes V, Testa G, Ansorge W, Stewart AF. 2000. Point mutation of bacterial artificial chromosomes by ET recombination. EMBO Rep. 1:239–243. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Buchholz F, Muyrers JP, Stewart AF. 1998. A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet. 20:123–128. 10.1038/2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan CK, Brignole EJ, Gibson W. 2002. Cytomegalovirus assemblin (pUL80a): cleavage at internal site not essential for virus growth; proteinase absent from virions. J. Virol. 76:8667–8674. 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8667-8674.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schenk P, Woods AS, Gibson W. 1991. The 45-kDa protein of cytomegalovirus (Colburn) B-capsids is an amino-terminal extension form of the assembly protein. J. Virol. 65:1525–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loveland AN, Chan CK, Brignole EJ, Gibson W. 2005. Cleavage of human cytomegalovirus protease pUL80a at internal and cryptic sites is not essential but enhances infectivity. J. Virol. 79:12961–12968. 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12961-12968.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chamberlain JP. 1979. Fluorographic detection of radioactivity in polyacrylamide gels with water-soluble fluor, sodium salicylate. Anal. Biochem. 98:132–135. 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90716-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gibson W. 1983. Protein counterparts of human and simian cytomegaloviruses. Virology 128:391–406. 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90265-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson W. 1996. Structure and assembly of the virion. Intervirology 39:389–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott DL, White SP, Otwinowski Z, Yuan W, Gelb MH, Sigler PB. 1990. Interfacial catalysis: the mechanism of phospholipase A2. Science 250:1541–1546. 10.1126/science.2274785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rozen R, Sathish N, Li Y, Yuan Y. 2008. Virion-wide protein interactions of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 82:4742–4750. 10.1128/JVI.02745-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bucks MA, Murphy MA, O'Regan KJ, Courtney RJ. 2011. Identification of interaction domains within the UL37 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 416:42–53. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vittone V, Diefenbach E, Triffett D, Douglas MW, Cunningham AL, Diefenbach RJ. 2005. Determination of interactions between tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 79:9566–9571. 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9566-9571.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siegel LM, Monty KJ. 1966. Determination of molecular weights and frictional ratios of proteins in impure systems by use of gel filtration and density gradient centrifugation. Application to crude preparations of sulfite and hydroxylamine reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 112:346–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erickson HP. 2009. Size and shape of protein molecules at the nanometer level determined by sedimentation, gel filtration, and electron microscopy. Biol. Proced. Online 11:32–51. 10.1007/s12575-009-9008-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erickson HP, Fowler WE. 1983. Electron microscopy of fibrinogen, its plasmic fragments and small polymers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 408:146–163. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb23242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. 2009. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4:363–371. 10.1038/nprot.2009.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee JH, Vittone V, Diefenbach E, Cunningham AL, Diefenbach RJ. 2008. Identification of structural protein-protein interactions of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 378:347–354. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Möhl BS, Böttcher S, Granzow H, Fuchs W, Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC. 2010. Random transposon-mediated mutagenesis of the essential large tegument protein pUL36 of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 84:8153–8162. 10.1128/JVI.00953-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Granzow H, Nixdorf R, Mettenleiter TC. 2002. Pseudorabies virus UL36 tegument protein physically interacts with the UL37 protein. J. Virol. 76:3065–3071. 10.1128/JVI.76.6.3065-3071.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]