Abstract

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) viruses cause severe and often fatal disease in humans. We evaluated the efficacy of repeated intravenous dosing of the neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) infection in cynomolgus macaques. Repeated dosing of peramivir (30 mg/kg/day once a day for 5 days) starting immediately after infection significantly reduced viral titers in the upper respiratory tract, body weight loss, and cytokine production and resulted in a significant body temperature reduction in infected macaques compared with that of macaques administered a vehicle (P < 0.05). Repeated administration of peramivir starting at 24 h after infection also resulted in a reduction in viral titers and a reduction in the period of virus detection in the upper respiratory tract, although the body temperature change was not statistically significant. The macaque model used in the present study demonstrated that inhibition of viral replication at an early time point after infection by repeated intravenous treatment with peramivir is critical for reduction of the production of cytokines, i.e., interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor α, gamma interferon, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, and IL-12p40, resulting in amelioration of symptoms caused by highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection.

INTRODUCTION

H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (HPAIVs) have severely affected the poultry industry and posed a serious threat to human health. H5N1 HPAIV infection of humans typically causes severe pneumonia, which often progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome and on occasion causes gastrointestinal symptoms, leukocytopenia, and lymphocytopenia (1). H5N1 HPAIV infection has also been associated with a systemic spread of the virus throughout the blood, with infectious virus being detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of some severely ill patients (2). As a result of the highly pathogenic nature of the virus, between 2003 and 2014, 650 confirmed human cases of H5N1 HPAIV infection were reported, with a fatality rate of >50% (3). Although these viruses have not acquired efficient transmissibility between humans, their wide geographical dissemination and high pathogenicity raise concern about the severity of a possible pandemic. Although vaccination plays a critical role in influenza prophylaxis, it takes time to produce a sufficient amount of vaccine to immunize a large proportion of humans upon the emergence of a new strain (4). Therefore, antiviral drugs are important for the treatment of infections with emerging viruses against which vaccines are under development.

Neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors, which target the conserved residues of the NA active site of both influenza A and B viruses, are recommended for the treatment of H5N1 HPAIV infection (5, 6). In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that H5N1 HPAIVs were sensitive to NA inhibitors, including oseltamivir, zanamivir, laninamivir, and peramivir (7–9). Of these, oseltamivir has been the most widely used and was demonstrated to improve the survival of patients, although oseltamivir-resistant H5N1 HPAIVs with mutations at positions H275Y and N295S (N1 numbering) of the NA were isolated from patients during antiviral treatment (10).

H5N1 HPAIVs differ from seasonal influenza viruses in replication efficiency and induction of cytokine responses. In human cases, the levels of viral RNA in the pharynx were higher for longer detection periods in H5N1 HPAIV-infected individuals than in individuals infected with seasonal influenza virus. In addition, the viral RNA was detected in the rectums and blood of more than 50% of the individuals infected with H5N1 HPAIV but not in those of individuals infected with seasonal influenza virus (1, 2). Because the disease caused by H5N1 HPAIVs is very severe in some cases, the current treatment approved for seasonal influenza virus infection might not be optimal. Previous animal studies suggest that the amounts of oseltamivir and zanamivir needed for the treatment of H5N1 HPAIV infection are larger than those recommended for the treatment of seasonal influenza virus infection (11–14). Therefore, to regulate infection with H5N1 HPAIVs, further optimization of antiviral regimens, including the route and duration of administration and combinations of antivirals, is required.

Peramivir is an anti-influenza virus drug that selectively inhibits the NA of human type A and B influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo (15, 16) and is approved as an intravenous preparation in the market in Japan (17–19) and also approved in South Korea (18). In randomized, controlled, and double-blind studies with adults, a single dose of peramivir was demonstrated to significantly reduce the duration of seasonal influenza virus infection without safety concerns. On the basis of these results, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization for intravenous peramivir exclusively for patients hospitalized because of infection associated with H1N1 pandemic virus on 23 October 2009, even though it was still under development in the United States (20). Also, the Chinese Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of peramivir for use in an H7N9 outbreak in China on 6 April 2013 (21), with an expectation of the most important characteristic of peramivir, i.e., rapid bioavailability after intravenous administration to patients with severe symptoms. Therefore, peramivir may be administered as a first-line therapy, especially to patients who have high-risk factors for complications or cannot take oral or inhaled drugs.

Repeated intravenous injections of peramivir for 5 days was able, without major detrimental effects, to reduce the median duration of illness in influenza virus-infected patients at high risk for complications (22). Animal studies with mice and ferrets showed that repeated intramuscular injections of peramivir were effective against infection with HPAIV A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) (7, 23). Although mouse and ferret models have provided insight into the pathogenesis of H5N1 HPAIV in mammalian hosts, the pathogenicity in those models cannot be directly extrapolated to humans. In our previous studies, though the mortality rate in cynomolgus macaques due to H5N1 HPAIVs was lower than that in humans, H5N1 HPAIVs induced severe pneumonia and symptoms in cynomolgus macaques, compared with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, as reported in human patients (24–26). Therefore, the use of cynomolgus macaques enabled not only analysis of the pathogenicity of various influenza viruses but also evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines and antiviral agents (27). In the present study, we infected cynomolgus macaques with influenza virus A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1), which was isolated from an index case in Vietnam in 2004 (28), and examined not only the severity of clinical symptoms and the duration of virus detection but also the production of cytokines and chemokines by the host immune system in response to virus infection. Thereafter, we examined the therapeutic efficacy of peramivir against H5N1 HPAIV infection in cynomolgus macaques in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compound.

Peramivir hydrate was synthesized and provided by Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

Virus and cells.

Influenza virus A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) was isolated from the same specimen as A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) (28). Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown in minimum essential medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 100 μg/ml kanamycin sulfate (Invitrogen) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. For virus titration, serial dilutions of swab samples, homogenized samples (10% [wt/vol] solution), and whole-blood samples were inoculated onto confluent MDCK cells as described previously (27). The presence of a cytopathic effect (CPE) was determined under a microscope 72 h later, and the mean 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) per milliliter of fluid or per gram of tissue was calculated. When no CPE was observed when using an undiluted sample solution, it was defined as an undetectable level that was considered to be lower than 1.4 log10 TCID50/ml (swab samples) or 2.4 log10 TCID50/g of tissue (tissue samples).

Cynomolgus macaques.

Approximately 4- to 6-year-old female cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) from the Philippines (Ina Research Inc., Ina, Japan) were used. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Husbandry and Management of Laboratory Animals of the Research Center for Animal Life Science at the Shiga University of Medical Science and Standards Relating to the Care and Management, etc., of Experimental Animals (notification 6, 27 March 1980, of the Prime Minister's Office, Japan) and after approval from the Shiga University of Medical Sciences Animal Experiment Committee and Biosafety Committee. In all procedures, macaques were anesthetized by intramuscular administration of ketamine (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg). CMK-2 food pellets (CLEA Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) were provided once a day after recovery from anesthesia, and drinking water was available ad libitum. Animals were housed singly under conditions of controlled humidity (27 to 48%), temperature (25 ± 1°C), and light (12-h light-dark cycle, lights on at 8:00 a.m.). Under anesthesia at least 1 week before virus inoculation, a telemetry probe (TA10CTA-D70; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) was implanted in the peritoneal cavity of each macaque for body temperature monitoring every 15 min. Body temperature was expressed by calculating the average temperature during nighttime (8 p.m. to 8 a.m.) to avoid the effects of anesthesia and was compared with that before virus inoculation. Individual macaques are distinguished by identification numbers. The animals were monitored every day during the study to be clinically scored as shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. One of the animals was euthanized because its clinical score reached 15 (a humane endpoint). For collection of tissue samples at the endpoint (7 or 8 days after virus inoculation), the other macaques were euthanized with ketamine-xylazine, followed by intravenous injection of pentobarbital (200 mg/kg). The macaques used in this study were free of herpes B virus, hepatitis E virus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Shigella species, Salmonella species, and Entamoeba histolytica. All experiments using viruses were performed in the biosafety level 3 facility of the Research Center for Animal Life Science, Shiga University of Medical Science.

Antiviral study in a cynomolgus macaque model.

The nostrils (0.5 ml per nostril), oral cavities (0.5 ml for the surface of each tonsil), and tracheas (5 ml) of cynomolgus macaques under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia were inoculated with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) (3 × 106 TCID50 in 7 ml of medium). Six or seven macaques were used in each group. The following three groups were compared in the macaque study. (i) Peramivir (30 mg/kg) in saline was administered intravenously to the first group once a day five times for 5 days. The first injection was performed immediately after infection on day 0 (peramivir day 0 group). (ii) Peramivir (30 mg/kg) in saline was administered intravenously once a day for 5 days starting on day 1 postinfection (p.i.) (peramivir day 1 group). (iii) Control animals inoculated with the virus but not treated with any reagents were intravenously administered saline from day 0 to day 4 in the same way as those in the peramivir day 0 group.

Under anesthesia, two cotton sticks (TE8201; Eiken Chemical, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used to collect nasal cavity, trachea, eye, and rectum swab samples and the sticks were subsequently immersed in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), penicillin, and streptomycin. A bronchoscope (MEV-2560; Machida Endoscope Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and cytology brushes (BC-203D-2006; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) were used to obtain bronchial samples. The brushes were quickly immersed in 1 ml of PBS containing 0.1% BSA, penicillin, and streptomycin. Blood samples were collected for the measurement of cytokine and chemokine levels in serum samples. Tissue samples were collected at autopsy and homogenized in a PBS solution at a 10% (wt/vol) final concentration for measurement of virus titers. Collected samples were stored at a temperature below −80°C until use.

Cytokine and chemokine measurements.

Levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12p40, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α [MIP-1α], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], monocyte chemotactic protein 1 [MCP-1], and gamma interferon [IFN-γ]) in tracheal swab fluid and serum samples were measured with the Milliplex MAP nonhuman primate cytokine panel and Luminex200 (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA).

Sequence analysis of NA genes.

Viral RNA was isolated directly from nasal and tracheal swab fluid from infected macaques by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). The NA region of influenza virus was amplified by PCR with a OneStep reverse transcription-PCR kit (Qiagen) and specific primers. The primers used for amplification of the NA region included forward primer 5′-CATCGGATCAATCTGTATGG-3′ or 5′-GTGTAAATGGCTCTTGCTTTACT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCTCATAGTGATAATTAGGAGC-3′ or 5′-GGTGAATGGCAACTCAGC-3′. The amplified DNA was sequenced by the TaKaRa sequencing service with an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA analyzer. The sequences of the NA regions derived from isolated viruses were compared with that of the inoculation virus, and amino acid substitutions were analyzed.

Statistical analysis.

Virus titers of each animal were calculated as the area under the curve (AUC) by the trapezoidal method, in which the areas of the trapezoidal segments were summed after virus titer curves were approximated by linear plots and AUCs were divided into small trapezoidal segments. Differences in virus titer AUCs were analyzed by Dunnett's multiple-comparison method. Dunnett's test was also used for comparisons of virus titers, body temperature changes, and cytokine and chemokine production levels each day. Statistical analysis was performed with the statistical analysis software SAS version 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Virus titers in macaques infected with H5N1 HPAIV and treated with intravenous peramivir.

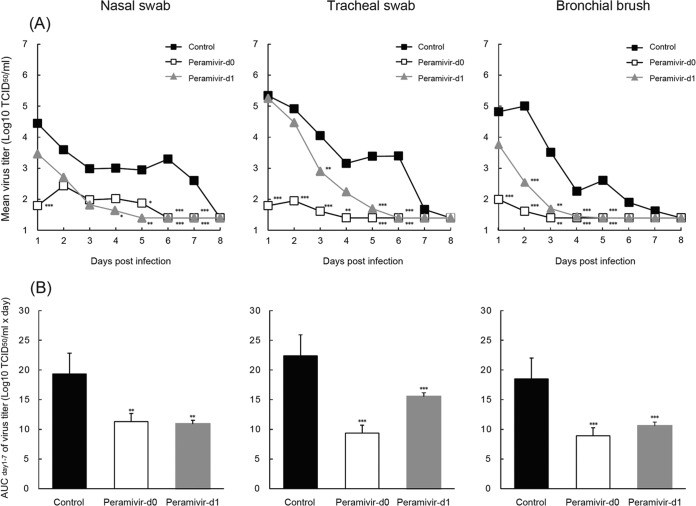

First, we examined the virus titers in swab fluid and bronchial brush samples from macaques inoculated with 3 × 106 TCID50 of A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1), the isolate obtained from an index case in Vietnam in 2004 (28). The viruses were detected in nasal, tracheal, and bronchial samples from the control group until day 7 p.i., and the virus titers in tracheal and bronchial samples were higher than those in nasal samples on days 1, 2, and 3 p.i. (Fig. 1A; see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). No virus was detected in conjunctival, rectal, or blood samples in this study (data not shown). To evaluate the efficacy of repeated administration of peramivir against H5N1 HPAIV in vivo, cynomolgus macaques inoculated with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) were intravenously administered peramivir at 30 mg/kg once a day for 5 days starting immediately after infection (peramivir day 0 group) or on day 1 p.i. (peramivir day 1 group; at that point, all of the macaques had a fever, as described below in detail). The amount of peramivir (30 mg/kg) used in the present study resulted in an AUC approximately 1.75 times larger than that obtained by the injection of 800 mg of peramivir into humans (in Japan, 300 mg/day was usually used for adult patients and 600 mg/day was approved for high-risk patients and those with complications) (27, unpublished data). In the early phase after infection until day 3, virus titers in the tracheal and bronchial samples of the peramivir day 0 group were significantly lower than those in the tracheal and bronchial samples of the control group (P < 0.01) and decreased to undetectable levels on days 4 and 3 p.i., respectively (Fig. 1A; see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). A significant reduction of virus titers in the tracheal and bronchial samples of the peramivir day 1 group was observed on days 3 and 2 p.i., respectively, compared with the titers in the tracheal and bronchial samples of the control group (P < 0.01). Moreover, virus was detected in the swab samples of the peramivir day 1 group for up to 5 days, whereas virus was detected for 7 days in the swab samples of the control group. One of the macaques in the peramivir day 1 group (no. 1487) was in a weakened condition and was euthanized 4 days after infection according to our humane endpoint (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Although pneumonia was evident in the lungs of this macaque upon histological examination at autopsy, the cause of the disease was unclear since the virus titer was controlled by the administration of peramivir (see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). Therefore, the results for this macaque were excluded from the following analysis. To analyze the effects of peramivir against total virus replication during infection, the areas under the virus titer curves (virus titer AUCs) from day 1 to day 7 p.i. were calculated. Significant differences between the average virus titer AUCs of the nasal, tracheal, and bronchial samples from the macaques treated with peramivir and those of samples from the macaques not treated with peramivir were observed (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Virus titers in nasal, tracheal, and bronchial swab fluids of infected cynomolgus macaques treated with peramivir. Macaques were inoculated with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) on day 0. Peramivir (30 mg/kg) in saline was administered intravenously once a day for 5 days starting immediately after virus inoculation (Peramivir-d0) or on day 1 p.i. (Peramivir-d1). (A) Virus titers in nasal, tracheal, and bronchial swab samples collected on the days indicated after virus inoculation are shown as mean titers of six or seven animals (see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). Standard deviations are <1.5 log10 TCID50/ml. Significant differences between the nasal, tracheal, and bronchial virus titers of the peramivir day 0 and control groups were observed on days 1, 5, 6, and 7, days 1 to 6, and days 1 to 5 p.i., respectively. Significant differences between the nasal, tracheal, and bronchial virus titers of the peramivir day 1 and control groups were observed on days 4 to 7, days 3, 5, and 6, and days 2 to 5 p.i., respectively. (B) Virus titer AUCs were calculated by use of the trapezoidal rule on the basis of the virus titers (log10 TCID50/ml) on days 1 to 7. The peramivir day 0 and 1 groups show a virus titer AUC statistically significantly smaller than that of the control group (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

We measured the virus titers in tissue samples collected at autopsy. The virus was detected in both the upper and lower respiratory tract tissues of the control group on day 7 p.i., while the number of organs in which the virus was detected in macaques in both peramivir groups, except for no. 1264, was lower than that of the control group (Table 1). In the tissue samples collected at autopsy on day 8 p.i., the virus was detected mainly in the tonsils of the control group, while the virus was detected in a tonsil of a macaque in the peramivir day 0 group (no. 1363) and in the oronasopharynx mucosa and tonsils of the macaques in the peramivir day 1 group (Table 2). No virus was detected in other organs of the macaques infected with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1). Furthermore, histological analysis of lung tissue obtained from the infected macaques revealed no significant difference in inflammation between the groups treated with peramivir and the control group (data not shown). To monitor the emergence of resistant variants during or after peramivir treatment, NA gene sequences of viruses obtained from nasal, tracheal, and bronchial samples and tissue samples collected at autopsy were determined. The viruses isolated from macaques treated with peramivir showed no mutation in the amino acid sequence of NA (275H) (Sanger sequencing) compared to the NA sequence of the virus inoculated into macaques on day 0.

TABLE 1.

Virus titers in tissues from infected cynomolgus macaques on day 7 p.i.

| Tissuea | Virus titer (log10 TCID50/g) on day 7 p.i.b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

Peramivir day 0 |

Peramivir day 1 |

|||||||

| 996c | 998 | 1013 | 840 | 845 | 853 | 1264 | 1270 | 1278 | |

| Nasal mucosa | 2.4 | <d | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Oronasopharynx | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | < | < | < | 5.2 | < | < |

| Tonsils | |||||||||

| Right | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.6 | < | < | < | < | 4.0 | < |

| Left | 5.9 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 4.0 | < | < | < | 4.7 | < |

| Trachea | 2.6 | < | 5.0 | < | < | < | 3.3 | < | < |

| Bronchi | |||||||||

| Right | 2.4 | < | 5.7 | < | < | < | 3.3 | < | < |

| Left | 2.4 | < | 4.7 | < | < | < | 2.6 | < | < |

| Lungs | |||||||||

| Right | |||||||||

| Upper | 3.6 | < | 2.6 | < | < | < | 4.7 | < | < |

| Middle | 2.9 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 3.3 | < | 3.1 | < | < |

| Lower | 2.4 | < | < | < | < | < | 4.8 | < | < |

| Left | |||||||||

| Upper | < | < | < | 4.0 | < | < | 4.3 | < | < |

| Middle | 5.4 | 5.2 | 2.4 | < | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.3 | < | < |

| Lower | 4.1 | < | < | 2.6 | < | < | 5.5 | < | < |

Tissue homogenates were prepared as a 10% (wt/vol) solution, and virus titers of individual samples are shown.

Cynomolgus macaques were inoculated with 3 × 106 TCID50 of virus on day 0. Treatment was initiated on day 0 or day 1. Tissue samples were collected on day 7 after virus inoculation.

Macaque identification number.

<, below detection limit of 2.4 log10 TCID50/g of tissue (= 1.4 log10 TCID50/ml of fluid).

TABLE 2.

Virus titers in tissues from infected cynomolgus macaques on day 8 p.i.

| Tissuea | Virus titer (log10 TCID50/g) on day 8 p.i.b |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

Peramivir day 0 |

Peramivir day 1 |

|||||||||

| 1360c | 1361 | 1362 | 1252 | 1363 | 1364 | 1365 | 1485 | 1486 | 1352 | 1358 | |

| Nasal mucosa | <d | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Oronasopharynx | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | 3.3 | 3.8 | < |

| Tonsils | |||||||||||

| Right | 2.7 | 4.1 | < | 3.6 | < | < | < | < | < | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| Left | 2.6 | 3.4 | < | < | 2.4 | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Trachea | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Bronchi | |||||||||||

| Right | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Left | < | 2.4 | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Lungs | |||||||||||

| Right | |||||||||||

| Upper | < | 2.6 | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Middle | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Lower | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Left | |||||||||||

| Upper | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Middle | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| Lower | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

Tissue homogenates were prepared as a 10% (wt/vol) solution, and virus titers of individual samples are shown.

Cynomolgus macaques were inoculated with 3 × 106 TCID50 of virus on day 0. Treatment was initiated on day 0 or day 1. Tissue samples were collected on day 8 after virus inoculation.

Macaque identification number.

<, below detection limit of 2.4 log10 TCID50/g of tissue (= 1.4 log10 TCID50/ml of fluid).

Symptoms of macaques infected with H5N1 HPAIV and treated with peramivir.

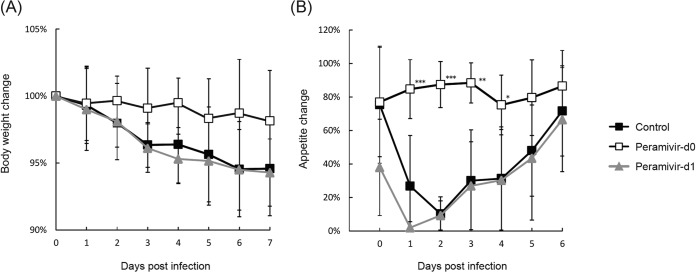

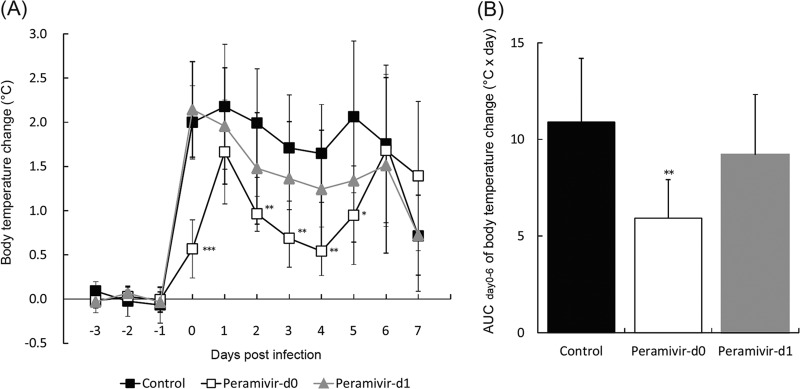

We examined the body temperature changes in macaques after inoculation with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1). Higher body temperatures than that before inoculation were observed in the control group until day 7 p.i. (Fig. 2A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The peramivir day 0 group had body temperatures significantly lower than those of the control group (P < 0.01) on the day of virus inoculation and days 2 to 5 p.i., and suppression of an increase in body temperature was statistically significant in the analysis of the AUC of body temperature change (Fig. 2B). While the average body temperature of the macaques in the peramivir day 1 group was substantially lower than that of the macaques in the control group during treatment, the difference was not statistically significant.

FIG 2.

Body temperatures of cynomolgus macaques treated with peramivir. Macaques were infected and treated as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Averages and standard deviations are shown. (A) Body temperatures were calculated from average temperatures during the night (8 p.m. to 8 a.m.), and the body temperature after virus inoculation was compared with that before virus inoculation. A significantly lower average body temperature of the peramivir day 0 group than that of the control group was observed on days 0 and 2 to 5 p.i. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed between the peramivir day 1 and control groups. (B) Body temperature change AUCs calculated by use of the trapezoidal rule on the basis of the body temperature change on days 0 to 6. The peramivir day 0 group shows a body temperature change AUC statistically significantly smaller than that of the control group (**, P < 0.01).

After infection with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1), appetite loss and weight loss were observed in all of the macaques in the control group (Fig. 3A). The average weight of macaques in the control group after the challenge as a percentage of that before the challenge was 95% ± 4%, while those of macaques in the peramivir day 0 and 1 groups were 98% ± 4% and 94% ± 3%, respectively. Macaques in the peramivir day 0 group did not show a loss of appetite during the observation period, and a significant difference in the average percent appetite (after the challenge versus before the challenge) between the peramivir day 0 and control groups was observed on days 1 to 4 p.i. (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). In addition, the peramivir day 1 group showed a reduction of body weight and a loss of appetite after infection, as observed in the control group, showing the importance of early treatment.

FIG 3.

Body weights and appetites of cynomolgus macaques inoculated with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1). (A) Body weights on the days indicated were calculated as percentages of the body weight before inoculation with virus. (B) Pellets were counted at feeding and at night before the room light was turned off. Appetite was reflected by the amount of food consumed, which was calculated from the numbers of residual and fed pellets. The appetite percentage was calculated as follows: % appetite = 100 × [(number of fed pellets − number of residual pellets)/number of fed pellets]. Significant differences between the percent appetite averages of the peramivir day 0 and control groups were observed on days 1 to 4 p.i. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

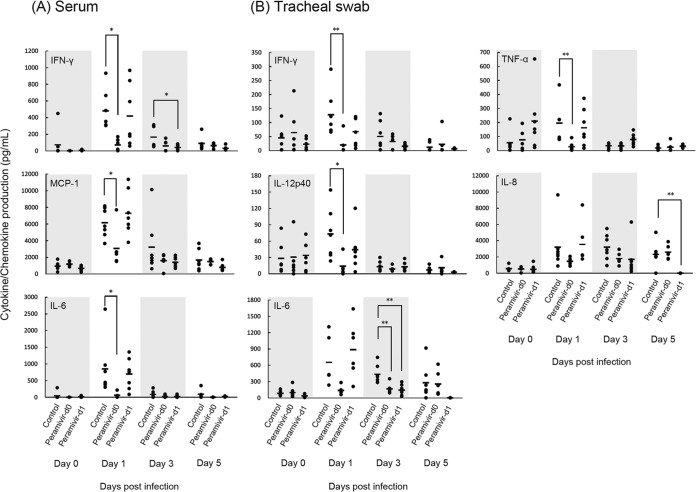

Cytokine responses in macaques infected with H5N1 HPAIV after treatment with peramivir.

Finally, we examined the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in serum and tracheal samples on day 0 before infection and on days 1, 3, and 5 p.i. The average levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1, and IL-6 in the serum of the peramivir day 0 group were significantly lower than those in the serum of the control group on day 1 p.i. (Fig. 4A). The average level of IFN-γ in the serum of the peramivir day 1 group was significantly lower than that in the serum of the control group on day 3 p.i. IL-1β, MIP-1α, TNF-α, and IL-12p40 were not detected in serum during the course of the study. IL-8 was detected in serum, but the levels did not differ from the preinfection levels (data not shown). On the other hand, the IFN-γ, IL-12p40, and TNF-α levels in the tracheal samples of the peramivir day 0 group were significantly lower than those in the tracheal samples of the control group on day 1 p.i. (Fig. 4B). Although no statistically significant differences in IL-6 production were found on day 1 p.i., the concentrations of IL-6 in the tracheal samples of both peramivir groups on day 3 p.i. were significantly lower, on average, than those in the tracheal samples of the control group. Levels of IL-8 in tracheal samples were also elevated in infected macaques in the control group, with a statistically significant difference between the peramivir day 1 and control groups on day 5. Although MCP-1 and MIP-1α were detected in the tracheal samples of all of the macaques, the levels of these chemokines did not differ from the preinfection levels (data not shown). Therefore, treatment with peramivir reduced the levels of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production in the serum and tracheas of macaques infected with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1).

FIG 4.

Inflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses of infected cynomolgus macaques. The levels of various cytokines and chemokines in serum and tracheal swab fluid samples from cynomolgus macaques infected with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) were measured. The concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in samples from individual macaques are plotted as dots. Bars indicate averages. Significant differences between the average cytokine levels of the peramivir day 0 and control groups were observed on days 1 and 3 p.i. and between the peramivir day 1 and control groups on days 3 and 5 p.i. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Several animal studies of H5N1 HPAIV have indicated that a high rate of viral replication and disseminated viral replication are important for disease pathogenesis and that cytokine dysregulation induced by infection may contribute to disease severity (1). In the present study, we revealed that HPAIV A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1) replicated in the upper and lower respiratory tracts of macaques and induced inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in their serum and tracheas, resulting in symptoms including fever and loss of appetite. In addition, tracheal and bronchial samples obtained from macaques infected with the virus showed more prolonged detection and substantially higher levels of virus than did those from macaques infected with seasonal influenza virus (29–31). Moreover, levels of IL-6, IFN-γ, and MCP-1 in serum were increased and levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were correlated with virus replication and symptoms (Fig. 1 and 4). These results are concordant with the results of previous studies on H5N1 HPAIV infection in humans showing that IL-6 and MCP-1 were released in response to influenza virus infection and that their concentrations in plasma were correlated with viral loads and influenza-related symptoms (1). These findings indicated that the macaque model mimics, to some extent, the pathogenicity in human patients, in whom a high viral replication level induced progressive illness. Therefore, control of viral replication by antivirals should be associated with good clinical outcomes.

It is often difficult to administer oral or inhaled drugs to patients with severe symptoms and those who require respiratory management. An intravenous drug rather than inhalants or oral drugs is suitable for such patients. In fact, clinical studies of intravenous injection of oseltamivir and zanamivir are ongoing in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Russia, Spain, Thailand, and the United Kingdom (32, 33). However, repeated intravenous administration of zanamivir after 4 h p.i. to macaques infected with HPAIV A/Hong Kong/156/1997 (H5N1) did not produce significant differences between the virus titers of the treatment and control groups (34). Our macaque study described here is the first to demonstrate the efficacy of repeated intravenous injections of peramivir against A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1), one of the most virulent human isolates. Our previous study showed the low toxicity of peramivir and its rapid uptake into the circulation following repeated intravenous injections into cynomolgus macaques (27). In the peramivir day 0 group, virus titers and levels of cytokines in the swab samples and body temperatures were lower than those in the control group. On the other hand, in the peramivir day 1 group, significant reductions in virus titers and cytokines in swab samples after treatment were observed, and body temperatures in the peramivir day 1 group showed a tendency to be lower than those of the control group, although the difference from the control group was not statistically significant. These results suggested that viral propagation in the early phase after virus infection contributed to the severity of symptoms, including fever, and that suppression of virus replication in the early phase during infection was critical for reduction of cytokine and chemokine production, resulting in amelioration of symptoms. In the peramivir day 1 group, however, the period of virus detection in the upper respiratory tract was shorter than that in the control group, indicating the possibility that transmission of virus to uninfected humans may be reduced even when administration of peramivir is initiated after onset of the disease.

In the present study, we administered peramivir for 5 days according to treatment of influenza virus infection with oseltamivir. However, body temperatures in the peramivir day 0 group rose on days 5 and 6 p.i. after the end of treatment and virus was detected on day 7 p.i. in the lung tissues of all of the macaques in the peramivir day 0 group. Virus was also detected on day 7 p.i. in the lung tissues of one of the macaques in the peramivir day 1 group (no. 1264), which showed a higher body temperature on days 5 and 6. These results suggest that virus in the lungs in the late phase causes a high body temperature. Therefore, treatment of HPAIV infection with peramivir for more than 5 days might be required for a further reduction of virus propagation and amelioration of symptoms since macaques infected with HPAIV occasionally showed fetal symptoms (22, 25, 26, 35).

The emergence of resistant mutants during antiviral treatment is a major concern. H5N1 HPAIVs with the H275Y or N295S mutation (N1 numbering), showing resistance to NA inhibitors, were identified in patients after oseltamivir treatment (10). In a clinical study of peramivir in high-risk patients, repeated intravenous injections of peramivir were thought to be effective in patients infected with influenza virus, including the H275Y NA mutants that prevailed worldwide in the 2008-2009 season since the peak plasma peramivir concentrations were higher than the in vitro 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of peramivir for H275Y NA mutants (22). In the present study with macaques, intravenous administration of peramivir at 30 mg/kg should achieve a maximum drug concentration in serum of up to 160 μg/ml (27), which is 2,500,000 times as high as the IC50 (0.06 ng/ml = 0.171 nM) for A/Vietnam/1203/2004 isolated from the same patient infected with A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (8). The concentration of peramivir in plasma dropped quickly after injection, but the level of peramivir at 24 h postdosing (52.4 ng/ml) was still about 870 times as high as the IC50 for A/Vietnam/1203/2004. Moreover, the IC50 for a recombinant virus with the H275Y NA mutation (4.26 ng/ml) was below the plasma peramivir concentration expected at 24 h postdosing (36). Therefore, the high concentration of peramivir in plasma during treatment is thought to be effective at reducing the risk of the emergence of mutants resistant to NA inhibitors. However, further studies are needed to determine how effective antiviral agents might be against H5N1 HPAIVs with the H275Y or N295S mutation.

In the present study, we demonstrated that repeated intravenous injections of peramivir had beneficial effects on viral titers and symptoms in macaques infected with HPAIV A/Vietnam/UT3040/2004 (H5N1). Therefore, repeated intravenous injections of peramivir would be an alternative for patients with H5N1 HPAIV infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Takahiro Nakagawa for animal care, Mutsumi Ito for preparation of virus, and Makoto Kodama and Tomoyuki Homma for valuable discussions.

All of the work reported here was financially supported by Shionogi Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02817-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, Chau NV, Khanh TH, Dong VC, Qui PT, Cam BV, Ha do Q, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Chinh NT, Hien TT, Farrar J. 2006. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 12:1203–1207. 10.1038/nm1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jong MD, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Vo MH, Tran TT, Nguyen BH, Beld M, Le TP, Truong HK, Nguyen VV, Tran TH, Do QH, Farrar J. 2005. Fatal avian influenza A (H5N1) in a child presenting with diarrhea followed by coma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:686–691. 10.1056/NEJMoa044307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2014. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A (H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/H5N1_cumulative_table_archives/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerdil C. 2003. The annual production cycle for influenza vaccine. Vaccine 21:1776–1779. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schünemann HJ, Hill SR, Kakad M, Bellamy R, Uyeki TM, Hayden FG, Yazdanpanah Y, Beigel J, Chotpitayasunondh T, Del Mar C, Farrar J, Tran TH, Ozbay B, Sugaya N, Fukuda K, Shindo N, Stockman L, Vist GE, Croisier A, Nagjdaliyev A, Roth C, Thomson G, Zucker H, Oxman AD. 2007. WHO Rapid Advice Guidelines for pharmacological management of sporadic human infection with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 7:21–31. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70684-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayden FG. 2006. Antivirals for influenza: historical perspectives and lessons learned. Antiviral Res. 71:372–378. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boltz DA, Ilyushina NA, Arnold CS, Babu YS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2008. Intramuscularly administered neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir is effective against lethal H5N1 influenza virus in mice. Antiviral Res. 80:150–157. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurt AC, Selleck P, Komadina N, Shaw R, Brown L, Barr IG. 2007. Susceptibility of highly pathogenic A (H5N1) avian influenza viruses to the neuraminidase inhibitors and adamantanes. Antiviral Res. 73:228–231. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiso M, Kubo S, Ozawa M, Le QM, Nidom CA, Yamashita M, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Efficacy of the new neuraminidase inhibitor CS-8958 against H5N1 influenza viruses. PLoS Pathog. 6(2):e1000786. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le QM, Kiso M, Someya K, Sakai YT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen KH, Pham ND, Ngyen HH, Yamada S, Muramoto Y, Horimoto T, Takada A, Goto H, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Kawaoka Y. 2005. Avian flu: isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. Nature 437:1108. 10.1038/4371108a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boltz DA, Rehg JE, McClaren J, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2008. Oseltamivir prophylactic regimens prevent H5N1 influenza morbidity and mortality in a ferret model. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1315–1323. 10.1086/586711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govorkova EA, Ilyushina NA, Boltz DA, Douglas A, Yilmaz N, Webster RG. 2007. Efficacy of oseltamivir therapy in ferrets inoculated with different clades of H5N1 influenza virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1414–1424. 10.1128/AAC.01312-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leneva IA, Goloubeva O, Fenton RJ, Tisdale M, Webster RG. 2001. Efficacy of zanamivir against avian influenza A viruses that possess genes encoding H5N1 internal proteins and are pathogenic in mammals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1216–1224. 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1216-1224.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen HL, Monto AS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2005. Virulence may determine the necessary duration and dosage of oseltamivir treatment for highly pathogenic A/Vietnam/1203/04 influenza virus in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 192:665–672. 10.1086/432008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babu YS, Chand P, Bantia S, Kotian P, Dehghani A, El-Kattan Y, Lin TH, Hutchison TL, Elliott AJ, Parker CD, Ananth SL, Horn LL, Laver GW, Montgomery JA. 2000. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): discovery of a novel, highly potent, orally active, and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 43:3482–3486. 10.1021/jm0002679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govorkova EA, Leneva IA, Goloubeva OG, Bush K, Webster RG. 2001. Comparison of efficacies of RWJ-270201, zanamivir, and oseltamivir against H5N1, H9N2, and other avian influenza viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2723–2732. 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2723-2732.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohno S, Kida H, Mizuguchi M, Shimada J. 2010. Efficacy and safety of intravenous peramivir for treatment of seasonal influenza virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4568–4574. 10.1128/AAC.00474-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohno S, Yen MY, Cheong HJ, Hirotsu N, Ishida T, Kadota J, Mizuguchi M, Kida H, Shimada J. 2011. Phase III randomized, double-blind study comparing single-dose intravenous peramivir with oral oseltamivir in patients with seasonal influenza virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:5267–5276. 10.1128/AAC.00360-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugaya N, Kohno S, Ishibashi T, Wajima T, Takahashi T. 2012. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of intravenous peramivir in children with 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:369–377. 10.1128/AAC.00132-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Drug Administration. 2009. News and events: FDA authorizes emergency use of intravenous antiviral peramivir for 2009 H1N1 influenza for certain patients, settings. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm187813.htm [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. 2013. China-WHO joint mission on human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, 18-24 April 2013, mission report, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/ChinaH7N9JointMissionReport2013u.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohno S, Kida H, Mizuguchi M, Hirotsu N, Ishida T, Kadota J, Shimada J. 2011. Intravenous peramivir for treatment of influenza A and B virus infection in high-risk patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2803–2812. 10.1128/AAC.01718-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun NE, Linde NS, Zacks MA, Barr IG, Hurt AC, Smith JN, Dziuba N, Holbrook MR, Zhang L, Kilpatrick JM, Arnold CS, Paessler S. 2008. Injectable peramivir mitigates disease and promotes survival in ferrets and mice infected with the highly virulent influenza virus, A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1). Virology. 374:198–209. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itoh Y, Ozaki H, Tsuchiya H, Okamoto K, Torii R, Sakoda Y, Kawaoka Y, Ogasawara K, Kida H. 2008. A vaccine prepared from a nonpathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus strain confers protective immunity against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection in cynomolgus macaques. Vaccine 26:562–572. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama M, Shichinohe S, Itoh Y, Ishigaki H, Kitano M, Arikata M, Pham VL, Ishida H, Kitagawa N, Okamatsu M, Sakoda Y, Ichikawa T, Tsuchiya H, Nakamura S, Le QM, Ito M, Kawaoka Y, Kida H, Ogasawara K. 2013. Protection against H5N1 highly pathogenic avian and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus infection in cynomolgus monkeys by an inactivated H5N1 whole particle vaccine. PLoS One 8(12):e82740. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoh Y, Yoshida R, Shichinohe S, Higuchi M, Ishigaki H, Nakayama M, Pham VL, Ishida H, Kitano M, Arikata M, Kitagawa N, Mitsuishi Y, Ogasawara K, Tsuchiya H, Hiono T, Okamatsu M, Sakoda Y, Kida H, Ito M, Le QM, Kawaoka Y, Miyamoto H, Ishijima M, Igarashi M, Suzuki Y, Takada A. 2014. Protective efficacy of passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies in animal models of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 10(6):e1004192. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitano M, Itoh Y, Kodama M, Ishigaki H, Nakayama M, Ishida H, Baba K, Noda T, Sato K, Nihashi Y, Kanazu T, Yoshida R, Torii R, Sato A, Ogasawara K. 2011. Efficacy of single intravenous injection of peramivir against influenza B virus infection in ferrets and cynomolgus macaques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4961–4970. 10.1128/AAC.00412-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le QM, Ito M, Muramoto Y, Hoang PV, Vuong CD, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Kiso M, Ozawa M, Takano R, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Pathogenicity of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza A viruses isolated from humans between and 2008 in northern Vietnam. J. Gen. Virol. 91(Pt 10):2485–2490. 10.1099/vir.0.021659-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maines TR, Lu XH, Erb SM, Edwards L, Guarner J, Greer PW, Nguyen DC, Szretter KJ, Chen LM, Thawatsupha P, Chittaganpitch M, Waicharoen S, Nguyen DT, Nguyen T, Nguyen HH, Kim JH, Hoang LT, Kang C, Phuong LS, Lim W, Zaki S, Donis RO, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. 2005. Avian influenza (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J. Virol. 79:11788–11800. 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11788-11800.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitano M, Itoh Y, Kodama M, Ishigaki H, Nakayama M, Nagata T, Ishida H, Tsuchiya H, Torii R, Baba K, Yoshida R, Sato A, Ogasawara K. 2010. Establishment of a cynomolgus macaque model of influenza B virus infection. Virology 407:178–184. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pham VL, Nakayama M, Itoh Y, Ishigaki H, Kitano M, Arikata M, Ishida H, Kitagawa N, Shichinohe S, Okamatsu M, Sakoda Y, Tsuchiya H, Nakamura S, Kida H, Ogasawara K. 2013. Pathogenicity of pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus in immunocompromised cynomolgus macaques. PLoS One 8(9):e75910. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan BJ, Davies B, Cirrincione-Dall G, Morcos PN, Beryozkina A, Chappey C, Aceves Baldó P, Lennon-Chrimes S, Rayner CR. 2012. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of intravenous oseltamivir: single- and multiple-dose phase I studies with healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4729–4737. 10.1128/AAC.00200-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marty FM, Man CY, van der Horst C, Francois B, Garot D, Manez R, Thamlikitkul V, Lorente JA, Alvarez-Lerma F, Brealey D, Zhao HH, Weller S, Yates PJ, Peppercorn AF. 2014. Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous zanamivir treatment in hospitalized adults with influenza: an open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study. J. Infect. Dis. 209:542–550. 10.1093/infdis/jit467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stittelaar KJ, Tisdale M, van Amerongen G, van Lavieren RF, Pistoor F, Simon J, Osterhaus AD. 2008. Evaluation of intravenous zanamivir against experimental influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in cynomolgus macaques. Antiviral Res. 80:225–228. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitano M, Kodama M, Itoh Y, Kanazu T, Kobayashi M, Yoshida R, Sato A. 2013. Efficacy of repeated intravenous injection of peramivir against influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2286–2294. 10.1128/AAC.02324-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abed Y, Pizzorno A, Boivin G. 2012. Therapeutic activity of intramuscular peramivir in mice infected with a recombinant influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) virus containing the H275Y neuraminidase mutation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4375–4380. 10.1128/AAC.00753-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.