Abstract

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonstructural 5A (NS5A) protein is a clinically validated target for drugs designed to treat chronic HCV infection. This study evaluated the in vitro activity, selectivity, and resistance profile of a novel anti-HCV compound, samatasvir (IDX719), alone and in combination with other antiviral agents. Samatasvir was effective and selective against infectious HCV and replicons, with 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) falling within a tight range of 2 to 24 pM in genotype 1 through 5 replicons and with a 10-fold EC50 shift in the presence of 40% human serum in the genotype 1b replicon. The EC90/EC50 ratio was low (2.6). A 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of >100 μM provided a selectivity index of >5 × 107. Resistance selection experiments (with genotype 1a replicons) and testing against replicons bearing site-directed mutations (with genotype 1a and 1b replicons) identified NS5A amino acids 28, 30, 31, 32, and 93 as potential resistance loci, suggesting that samatasvir affects NS5A function. Samatasvir demonstrated an overall additive effect when combined with interferon alfa (IFN-α), ribavirin, representative HCV protease, and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitors or the nucleotide prodrug IDX184. Samatasvir retained full activity in the presence of HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) antivirals and was not cross-resistant with HCV protease, nucleotide, and nonnucleoside polymerase inhibitor classes. Thus, samatasvir is a selective low-picomolar inhibitor of HCV replication in vitro and is a promising candidate for future combination therapies with other direct-acting antiviral drugs in HCV-infected patients.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 150 million people are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en). In the United States, >4 million people suffer from persistent HCV infection, and 10,000 people die annually from HCV-related liver diseases, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Morbidity and mortality rates from chronic HCV infection are projected to double in this decade and may surpass those of human immunodeficiency virus (1). To date, three protease inhibitors and a nucleotide prodrug inhibitor of the HCV polymerase have been approved for HCV treatment in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. However, due to the possible emergence of resistant viruses upon single-drug therapy and the side effects related to treatment with protease inhibitors (2–5) (see http://www.jnj.com/news/all/OLYSIO-simeprevir-Receives-FDA-Approval-for-Combination-Treatment-of-Chronic-Hepatitis-C), additional potent and safe direct-acting antiviral agents are needed to effectively combat this disease.

The HCV genome consists of approximately 9,600 nucleotides of positive single-stranded RNA that encode a ∼3,033-amino acid polyprotein. Upon cleavage by cellular and viral proteases, the polyprotein is processed into 10 viral proteins. The four amino-terminal structural proteins function in the formation of viral particles. The six carboxy-terminal nonstructural proteins process the viral polyprotein, serve in host and viral regulatory roles, participate in the formation of the viral replication complex, and/or contribute to replication of the viral genome (6).

The nonstructural 5A (NS5A) protein is involved in the replication and maturation of HCV virions and has been shown to interact with numerous host cell proteins (7). Although the exact functions of the NS5A protein are not fully understood, inhibitors of NS5A have been identified through replicon screening and are in various stages of clinical development (6, 8–10). The first such inhibitor, daclatasvir (BMS-790052), was active against the replicon, with 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) ranging from 9 to 146 pM, depending upon the HCV genotype (8). The activity of daclatasvir is markedly lower against genotype 2 and 3 intergenotypic replicons than against those of genotypes 1, 4, and 5 (8). The NS5A inhibitor samatasvir (IDX719) was designed to inhibit HCV replication with enhanced activity across genotypes, potentially affording a once-daily single-pill dosing regimen for all genotypes. This study assesses the in vitro efficacy, specificity, and resistance phenotype of samatasvir, a novel HCV NS5A inhibitor, and demonstrates its role in a combination treatment regimen for HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

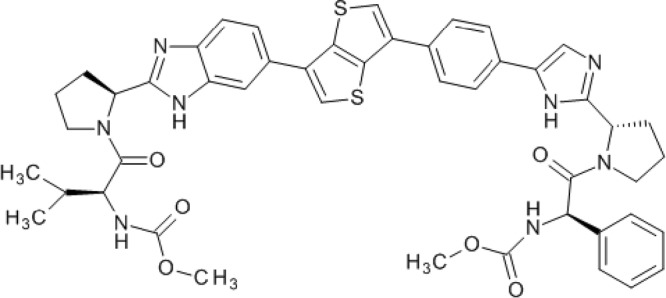

Samatasvir [carbamic acid, N-[(1R)-2-[(2S)-2-[5-[4-[6-[2-[(2S)-1-[(2S)-2-[(methoxycarbonyl)amino]-3-methyl-1-oxobutyl]-2-pyrrolidinyl]-1H-benzimidazol-6-yl]thieno[3,2-b]thien-3-yl]phenyl]-1H-imidazol-2-yl]-1-pyrrolidinyl]-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl]-, methyl ester] (Fig. 1), daclatasvir, and IDX184 were synthesized by Idenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Intron A and ribavirin (RBV) (Rebetol) were obtained from Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ). Doxorubicin hydrochloride, diclofenac sodium salt, and alpha-1 acid glycoprotein (AAG) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Efavirenz (EFV), lamivudine (3TC), lopinavir (LPV), ritonavir (RTV), RBV, telbivudine (LdT), tenofovir (TFV), and zidovudine (AZT) were obtained from Moravek Biochemicals and Radiochemicals (Brea, CA). Raltegravir was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX) (11). Lopinavir and ritonavir were mixed in a 4:1 ratio to constitute Kaletra (KLT).

FIG 1.

Molecular structure of samatasvir.

HCV replicons.

ZS11-luc (genotype 1b, Con1) and 1a-luc (strain H77) are bicistronic HCV replicons encoding the nonstructural proteins from NS3 to NS5B under the control of the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) promoter, as well as a firefly luciferase-neomycin phosphotransferase fusion gene under the control of the HCV promoter. The ZS11-luc replicon contains adaptive mutations encoding E1202G, S2204I, and D2254E, and the 1a-luc replicon contains adaptive mutations encoding Q1067R, P1496L, V1655I, K1691R, K2040R, and S2204I in the HCV polyprotein. SP1ΔS (genotype 1b, Con1) and H1a (genotype 1a, H77) are bicistronic HCV replicons that contain nonstructural regions from NS3 to NS5B under the EMCV IRES promoter. SP1ΔS contains a deletion at S2204 in NS5A for enhanced replication. The parental ZS11 (without luciferase) and SP1ΔS replicons were kindly provided by Christoph Seeger (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA).

Site-directed mutations on the wild-type 1a-luc or ZS11-luc replicons were generated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene/Agilent Technologies), as recommended by the manufacturer, and were confirmed by sequencing. cDNAs were transcribed after ScaI linearization using the RiboMAX large-scale RNA production system (Promega Corporation).

The NS5A intergenotypic (IGT) replicons were derived from the genotype 1b ZS11-luc replicon by removing the genotype 1b NS5A region and either substituting the first 100 amino acids of NS5A or amino acids 12 to 437 of NS5A from the desired genotype. The following genotypes and strains were used: genotype 1a (H77 strain), 2a (JFH-1 strain, GenBank accession no. AB047639), 3a (NZL-1 strain, D17763), 4a (F7157 strain, DQ418788), and 5a (SA13 strain, AF064490). The preliminary cDNA templates of NS5a for genotypes 2a, 3a, 4a, and 5a were synthesized by an outside vendor.

Viruses.

The JFH-1 DNA template was derived synthetically using sequence information from NCBI accession no. AB047639 (12). JFH-1 RNA, produced by in vitro transcription, was used to generate infectious virus by transfection of hepatitis C-producing (HPC) cells using a procedure similar to those previously reported (12, 13).

A panel of 17 RNA and DNA viruses was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), the BEI Research Resource Repository, and the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARRRP) and propagated by standard methods. With the exception of dengue virus, which was grown in Vero E6 cells, the stock virus pools for each of the viruses were grown in the same cell lines used for antiviral evaluations.

Cells and media.

The CAKI-1, CCRF-CEM, COLO-205, SJCRH30, and HepG2 cell lines, as well as those listed in Table 1, were obtained from the ATCC, MAGI-CCR5 cells were obtained from the NIH ARRRP (14), and the SNB-78 cell line was provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). All cell lines were maintained as suggested by the respective manufacturers. The Huh-7 (15) and HPC cell lines were kindly provided by Christoph Seeger (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) and were propagated in Huh-7 medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM] containing glucose, l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM GlutaMAX, and nonessential amino acids). The HepaRG cell line (Life Technologies) was maintained in the supplier's proprietary medium.

TABLE 1.

Antiviral activity of samatasvir against 17 RNA and DNA virusesa

| Genome type and virus family | Virus (strain) | Cell line | EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | |||

| Flaviviridae | Bovine viral diarrhea virus (NADL) | MDBK | 33.4 |

| Dengue virus, serotype 2 (New Guinea C) | Huh-7 | >50 | |

| West Nile virus (NY-99) | Vero | >50 | |

| Yellow fever virus (17D) | HeLa | 16.5 | |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A virus (A/Victoria/3/75 [H3N2]) | MDCK | >50 |

| Influenza B virus (Lee) | MDCK | >50 | |

| Paramyxoviridae | Measles virus (Edmonston) | HeLa | >50 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus (Long) | Vero | >50 | |

| Picornaviridae | Coxsackie B virus (B4) | Vero | >50 |

| Poliovirus (Chat) | Vero | >50 | |

| Rhinovirus (1B) | MRC-5 | >50 | |

| Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (Ba-L) | MAGI-CCR5 | >50 |

| Togaviridae | Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (Trinidad) | Vero E6 | >50 |

| Reoviridae | Rotavirus (WI61) | Vero | >50 |

| DNA | |||

| Herpesviridae | Herpes simplex virus 1 (HF) | Vero | >50 |

| Poxviridae | Monkeypox virus (Zaire) | Vero E6 | >50 |

| Vaccinia virus (WR-56) | Vero E6 | >50 |

The values are from a single data set. The samatasvir CC50 values for each cell line used were >50 μM.

The GS4.1 (16) (kindly provided by Christoph Seeger, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA), Zluc, H1a, and H1a-luc cell lines stably possess a bicistronic HCV genotype 1a or 1b replicon and were propagated in Huh-7 medium containing 0.25 to 0.5 mg/ml of G418 (Geneticin; Life Technologies). The NS5A intergenotypic (IGT) replicon cell lines stably possess bicistronic replicons containing the luciferase reporter gene and represent NS5A of genotype 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a, or 5a. These cells were maintained in Huh-7 medium containing 0.5 mg/ml of G418.

Cytotoxicity assays.

The cells were seeded and treated as in the replicon activity assay (described below). After 3 days of treatment, viability was determined with the CellTiter-Blue cell viability assay solution (Promega) in a Victor3 V 1420 multilabel counter (PerkinElmer), and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values were determined using the Microsoft Excel and XLFit 4.1 softwares.

HepG2 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were subjected to 3-day treatment with serial dilutions of compound, after which a 4-parameter In Cytotox toxicity test system was used as suggested by the manufacturer (Xenometrics). This test system consecutively monitors different cytotoxic endpoints, such as cell death (lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] assay), general physiological cell state (glucose consumption), metabolic activity (2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide [XTT] assay), and lysosomal activity (acid phosphatase) in the same well.

The CAKI-1, SNB-78, CCRF-CEM, SJCRH30, and COLO-205 cell lines were exposed to serial dilutions of samatasvir or daclatasvir for 3 days and then assessed for cell viability via CellTiter-Glo (Promega), as described above. Doxorubicin (10 μM) was used as a toxicity control.

Long-term cytotoxicity assays were performed with HepaRG cells (1 × 105 cells/well) in collagen I-coated 96-well plates that were maintained for 7 days in the recommended medium without drug to ensure terminal differentiation prior to drug exposure. The cells were treated with compound for 14 days and were refed every other day to ensure proper nutrition and exposure to the drug. At the end of treatment, cell viability was determined using the WST-1 cell proliferation solution (Clontech), and absorbance (450 nm) was measured in a Victor3 V 1420 multilabel counter. CC50 values were determined using the XLFit 4.1 software.

Non-HCV antiviral activity assays.

Depending on the virus, standard cytoprotection (cytoprotective effect [CPE]), reporter gene (HIV), or plaque reduction (vaccinia virus, monkeypox virus, or Venezuelan equine encephalitis [VEE] virus) assays were used to evaluate antiviral activity (17). The appropriate positive controls of virus inhibition were used for each virus. For each assay, an aliquot of virus whose titer had been previously determined was diluted into tissue culture medium such that the amount of virus added to each well was either the amount determined to give between 85 and 95% cell killing (CPE assays), approximately 10× the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)/well (reporter gene), or the required number of PFU per well (plaque reduction assays).

HCV replicon activity assay.

Solid opaque 96-well culture plates were seeded with Zluc, NS5A IGT (7.5 × 103 cells/well), or H1a-luc (1 × 104 cells/well) cells in Huh-7 medium. At least 4 h later, drug treatment was initiated and the cells incubated for 3 days at 37°C under 5% CO2. Luciferase activity was measured on a Victor3 V 1420 multilabel counter (1-s read time, 700-nm cutoff filter) using ONE-Glo luciferase assay reagent (Promega). The EC50s were calculated from dose-response curves from the resulting best-fit equations determined by the Microsoft Excel and XLFit 4.1 software programs.

HCV replicon combination assay.

Duplicate 96-well culture plates were seeded with Zluc and Huh-7 cells, respectively, at a density of 7.5 × 103 cells per well in Huh-7 medium. The cells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 3 to 4 h, and drug treatment was then initiated by adding drug dilutions in a 5-by-5 checkerboard design. The final concentrations of both drugs ranged from 0.25× to 4× their respective EC50s. Cytotoxicity was measured in parallel using the CellTiter-Blue cell viability assay solution (Promega).

The activity data were analyzed for synergism or antagonism using three mathematical models, (i) the Bliss independence model (MacSynergy II program, version 1.0; M. N. Prichard, L. E. Prichard, and C. Shipman, Jr., University of Michigan, MI, USA) (18, 19), (ii) Loewe additivity model (CombiTool program, version 2.001; V. Dressler, G. Muller, and J. Suhnel, Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, Jena, Germany) (20), and (iii) the median-effect approach (combination index, CalcuSyn program, version 2.1; Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom) (19–22). MacSynergy II calculates a theoretical additive dose-response surface based on the dose-response curves for each individually titrated drug. Peaks above the plane at 0% inhibition indicate areas of greater-than-additive interaction, or synergism. Conversely, peaks below the plane at 0% inhibition indicate areas of less-than-additive interaction, or antagonism. The data sets were assessed at the 99.9, 99, and 95% confidence levels; volumes of <25 μM2% (log volumes, <2) were considered additive, volumes of >25 but <50 μM2% (log volumes, >2 and <5, respectively) were considered weakly synergistic or antagonistic, volumes of >50 but <100 μM2% (log volumes, >5 and <9, respectively) were considered moderately synergistic or antagonistic, and volumes of >100 μM2% (log volumes, >9) were considered strongly synergistic or antagonistic. CombiTool calculates the differences between the predicted effects (according to the Loewe additivity model) and observed effects (experimental data) (20). Deviations of >0.25 from the predicted effects were considered significant. The CalcuSyn program, version 2.1 (Biosoft), was used to determine the nature of the drug-drug interaction based on the combination index equation proposed by Chou and Talalay (22). The combination index at the calculated EC50 for the drug combination was determined; the description of the degree of drug interaction based on the combination index (CI) value is as recommended in the CalcuSyn for Windows software manual. Analyses were performed on the data derived from at least five independent experiments.

For the protein binding experiments, Huh-7 medium containing 10 to 50% human sera (HS) (Valley Biomedical), 10% FBS plus 1 mg/ml AAG, or 10% FBS alone was used. The fold change in antiviral activity for each drug was calculated by dividing the EC50 in the respective medium by the reference EC50 in 10% FBS. In addition, the EC50s obtained in 10, 20, 30, 40, 45, and 50% HS for each drug were subjected to linear regression analysis using the XLFit 4.1 software to extrapolate the 100% serum-adjusted EC50. The cytotoxicity assays were run in parallel using MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] reagent (Promega).

For drug-drug interaction studies, the replicon cells were treated with serial dilutions of samatasvir in the presence of a fixed concentration of a hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HIV agent and 45% HS. The fixed concentrations used were five times the reported maximum concentration of drug in serum (Cmax) value: 94 μM KLT, 28 μM AZT, 32.5 μM 3TC, 5 μM TFV, 65 μM LdT, 65 μM EFV, and 27 μM raltegravir (RLT) (11, 23–28). The cytotoxicity assays were run in parallel using MTS reagent.

Extended-treatment replicon assay.

H1a cells were seeded into a 6-well plate (3 × 105 cells per well) in medium containing compounds and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. The cells were split every 3 to 4 days in medium containing fresh compound. On the days indicated, RNA was extracted using the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche) with DNase I treatment, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Replicon RNA was measured by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) in a StepOnePlus instrument using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR master mix (Life Technologies) containing 0.9 μM forward and reverse primers and 0.25 μM probe specific for the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of the replicon, and these were compared to an in vitro-transcribed standard curve. The primers used were as follows: forward, 5′-AGCCATGGCGTTAGTATGAGTGT-3′; reverse, 5′-TTCCGCAGACCACTATGG-3′. The probe was 5′-6FAM-CCTCCAGGACCCCCCCTCCC-TAMRA-3′ (6FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, tetramethylrhodamine). The replicon RNA values were normalized to human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) endogenous control (Life Technologies), using TaqMan control total human RNA (Life Technologies) for the standard curve. The log10 change from baseline of the HCV replicon for each RNA extraction day (days 3, 7, 10, and 14) in a single experiment was then calculated by subtracting the mean log10 HCV replicon copies/ng RNA of the sample from the mean log10 HCV replicon copies/ng RNA of the untreated control at day 0. The mean log10 change from baseline and standard deviation for each RNA extraction day were then calculated across the experiments in the analysis.

HCV in vitro infection core ELISA.

For an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), 96-well plates were seeded with HPC cells at a density of 2.5 × 103 cells per well in Huh-7 medium. At least 4 h after the HPC cells were seeded, JFH-1 HCV virus stock and serial dilutions of drug in Huh-7 medium were added to each well. At 16 h after treatment and infection, the virus inoculum and drug solution were removed by aspiration. The cultures were then treated at the same final concentrations of drug diluted in Huh-7 medium. The cells were incubated in the presence of drug for 4 additional days at 37°C under 5% CO2, upon which the cells were fixed with a 1:1 solution of acetone to methanol for 1 min, washed three times with KPL wash solution (KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), and then blocked with 10% FBS-TNE (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% FBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with KPL wash solution and incubated with an anti-hepatitis C virus core protein antibody (clone MA1-080; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) diluted in 10% FBS-TNE for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were washed as described above and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen) diluted in 10% FBS-TNE for 1 h at 37°C, and then washed. Color development was initiated by adding o-phenylenediamine (OPD) solution. After 30 min, the reaction was stopped with 2 N H2SO4 and the absorbance measured at 490 nm on a Victor3 V 1420 multilabel counter. The EC50s were calculated from dose-response curves from the resulting best-fit equations determined by the Microsoft Excel and XLFit 4.1 software programs.

Resistance selection.

H1a-luc cells were cultured in the presence of 0.25 mg/ml of G418 and increasing concentrations of samatasvir for 90 days to generate samatasvir-resistant cell lines in three independent experiments. Selection began with 2× the EC50 of samatasvir; untreated replicon cells were cultured in parallel. On day 0 and after selection, compound activity was evaluated in the replicon activity assay. Population sequencing of the genomic region corresponding to the amino-terminal 100 residues of NS5A was performed during selection. At the conclusion of the selection period, the NS3 to NS5b genomic sequence was determined by population sequencing. Finally, clonal sequencing of the NS5A amino-terminal region (encoding amino acids 1 to 100) from one samatasvir-resistant cell line (719R-A) and its matched untreated control replicon cell line was performed after selection.

Population and clonal sequencing.

RNA was extracted from cell pellets as per the manufacturer's protocol for the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics), including the optional DNase I digestion procedure. All RT-PCRs were carried out using the Easy-A one-tube RT-PCR system (Stratagene/Agilent Technologies). The entire replicon was sequenced using primers that overlapped each nonstructural gene: NS3F, 5′-CCTCGGTGCACATGCTTTACATGTGTTT-3′; NS3R, 5′-GACAATCCTGCCCACTATGACCAC-3′; NS4F, 5′-CCCTGACGCACCCAATCACCAAAT-3′; NS4R, 5′-CGCGCTGGCAGGACACAAAG-3′; NS5AF, 5′-GCACTACGTGCCGGAGAGCG-3′; NS5AR, 5′-CTGGAAGACAGTGTAACACC-3′; NS5BF, 5′-CGGATCTCAGCGACGGGTCATGGTC-3′; and NS5BR, 5′-GGAAAAAAACAGGATGGCC-3′. The region encoding the first 100 amino acids of NS5A was amplified using the following primers: forward, 5′-GCACTACGTGCCGGAGAGCG-3′, and reverse, 5′-GATTGTCAGTAGTCATACCC-3′. The resulting cDNAs were then sequenced with overlapping primers in both directions.

Clonal sequencing of the genomic region encoding the first 100 amino acids of NS5A was carried out using RT-PCR products per the TOPO TA Cloning kit for sequencing (Invitrogen) protocol and electroporated into One Shot TOP10 Electrocomp cells. One hundred individual bacterial colonies were expanded and purified using the Wizard SV 96 plasmid DNA purification system (Promega). The plasmids were sequenced with forward and reverse primers.

The sequences were assembled and compared against a wild-type replicon sequence from untreated H1a-luc cells using Sequencher 4.9 (Gene Codes Corporation) and aligned using GeneDoc (http://www.nrbsc.org/gfx/genedoc/ebinet.htm).

Transient-transfection assay.

Four million HPC cells were electroporated with the wild-type or mutant replicon RNA and plated (3 × 104 cells/well) on a 96-well opaque white plate (29). Approximately 4 h later, serial dilutions of drug were added and the plates incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 4 days. The experiment was performed as described above for the replicon activity assay to determine the EC50 of each drug against each of the mutant replicons. The activity was expressed as the mean fold change in EC50 relative to that of a wild-type genotype 1a, 1b, or intergenotypic 2a replicon.

To determine the replicative capacity of each mutant, two identical plates of transfected cells were plated without treatment. Luciferase activity was measured at 4 h and 4 days after plating for each mutant replicon and compared to that of the wild-type replicon. The replicative capacity of each mutant was expressed as a mean percentage of the wild-type replication activity.

RESULTS

Samatasvir is a selective inhibitor of HCV replication with broad genotypic activity.

Samatasvir inhibited genotype 1a and 1b HCV replicons at picomolar concentrations, with a mean CC50 value of >100 μM in the Zluc genotype 1b replicon cell line (Tables 2 and 3), giving rise to a selectivity index of >5 × 107. When tested against replicons bearing NS5A sequences from other genotypes or a genotype 2a JFH-1 infectious virus, EC50s of 2 to 24 pM were obtained. This represents a 12-fold change across the tested genotypes compared to an 84-fold change for daclatasvir (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antiviral potency against HCV genotypes 1 to 5

| Genotype | Virus/replicona | Mean EC50 ± SD (pM) ofb: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Samatasvir | Daclatasvir | ||

| 1a | H1a-luc | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 51 ± 11 |

| 100-IGT | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 84 ± 27 | |

| FL-IGT | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 80 ± 33 | |

| 1b | Zluc | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 13 ± 4 |

| 2a | JFH-1 virus | 21 ± 4 | 158 ± 50 |

| FL-IGT | 24 ± 4 | 176 ± 1 | |

| 3a | 100-IGT | 23 ± 11 | 1,086 ± 301 |

| FL-IGT | 17 ± 3 | 299 ± 4 | |

| 4a | 100-IGT | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 72 ± 66 |

| FL-IGT | 2.0 ± 0 | 19 ± 3 | |

| 5a | 100-IGT | 18 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 |

100-IGT, ZS11-luc replicon containing intergenotypic substitutions in amino acids 1 to 100 of NS5A; FL-IGT, ZS11-luc replicon containing intergenotypic substitutions in amino acids 12 to 437 of NS5A.

Data are from 3 to 5 independent experiments.

TABLE 3.

Cytotoxicity profile of samatasvir in human cell lines

| Cell line | Tissue | Mean CC50 ± SD (μM) of: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Samatasvir | Daclatasvir | ||

| Zluca,d | Liver | >100 | 19 ± 4 |

| HepaRGb,d,g | Liver | >100 | 23.7 ± 1.2 |

| CAKI-1c,e | Kidney | >50 | 25.5 ± 2.1 |

| CCRF-CEMc,e | Blood | >50 | 10.5 ± 2.1 |

| COLO-205c,e | Intestine | >50 | 17.0 ± 1.4 |

| SJCRH30c,e | Skeletal muscle | >50 | 14.5 ± 0.7 |

| SNB-78c,f | CNSh | >50 | 15.0 |

Three-day assay using CellTiter-Blue.

Fourteen-day assay using WST-1.

Three-day assay using X CellTiter-Glo.

n = 3.

n = 2.

n = 1.

Diclofenac (positive control) had a characteristic CC50 (mean ± SD) of 175.8 ± 14.2 μM.

CNS, central nervous system.

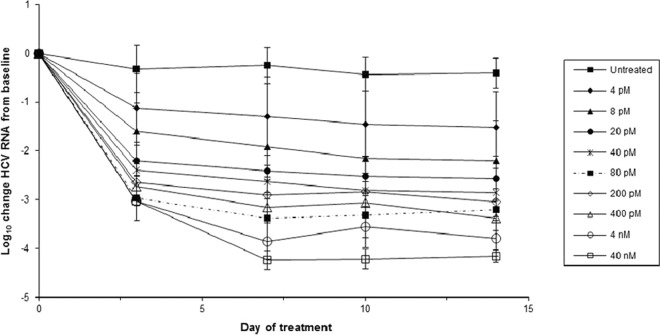

Samatasvir reduced genotype 1a replicon RNA in a dose-dependent manner over 14 days (Fig. 2). The maximum reductions were 1.5 and 4.2 log10 for 4 pM (1× the EC50) and 40 nM (10,000× the EC50), respectively. Depending on the drug concentration, there was a 1.1- to 3.0-log10 reduction in replicon RNA after 3 days of treatment, followed by a second lower rate of RNA reduction until day 7, when the RNA reductions reached a plateau. There was no evidence of replicon RNA rebound. Maximal suppression occurred at 7 to 14 days, depending on the dose.

FIG 2.

Reduction in genotype 1a HCV replicon RNA during a 14-day treatment with samatasvir. Genotype 1a replicon cells were treated with compound for 14 days, and RNA samples were collected on days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 (vertical lines). HCV replicon replication was measured by amplification of the HCV 5′-UTR by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and normalized to the total RNA, as measured by the housekeeping gene GAPDH, over the course of treatment. The log10 reduction value for the HCV replicon was calculated by subtracting the mean log10 HCV replicon copies/ng RNA of the sample from the mean log10 HCV replicon copies/ng RNA of the untreated control at day 0. The results from the replicates were averaged across 2 to 3 independent experiments and the standard deviation determined.

The specificity of samatasvir antiviral activity was tested against 17 RNA and DNA viruses, spanning several viral families (Table 1). Samatasvir showed weak antiviral activity against two additional members of the family Flaviviridae, bovine viral diarrhea virus (EC50, 33.4 μM) and yellow fever virus (EC50, 16.5 μM) but was inactive against all other tested viruses. Samatasvir was not toxic to any of the cell lines in the assays (CC50, >50 μM).

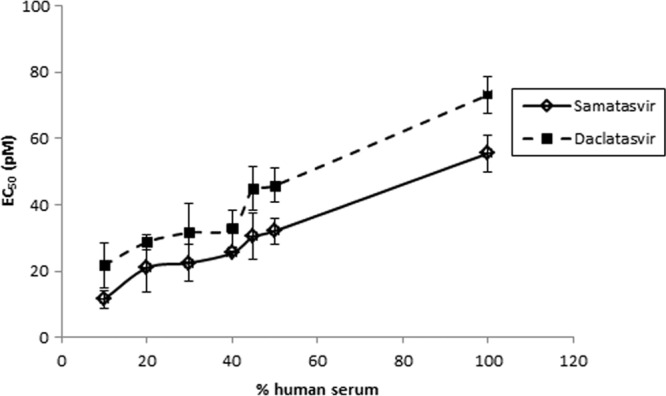

It is common for antiviral or other drugs to bind serum proteins, such as albumin or alpha-1 acid glycoprotein (AAG), and this binding has been associated with reduced drug efficacy (30, 31) (M.-P. de Bethune, D. Xie, H. Azijn, P. Wigerinck, R. Hoetelmans, and R. Pauwels, presented at the 9th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, 24 to 28 February 2002, and K. L. Limoli, L. H. Trinh, G. M. Heilek-Snyder, J. M. Weidler, N. S. Hellman, and C. J. Petropoulos, presented at the XIV International AIDS Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 7 to 12 July 2002). Therefore, the activity of samatasvir in the presence of human serum, which contains high concentrations of albumin (350 to 500 mg/ml) and a physiological concentration of purified AAG (1 mg/ml), was evaluated in the genotype 1b replicon. Albumin-containing FBS (10%) and AAG had minimal effect on samatasvir potency, whereas daclatasvir activity decreased 9.4-fold (Table 4). In the presence of 40% human serum, samatasvir activity decreased 10.4-fold (Table 4), compared to a 2.6-fold decrease for daclatasvir. The effects of human serum on the in vitro antiviral activities of samatasvir and daclatasvir are depicted in Fig. 3. Using EC50 and EC90 values obtained in 10% to 50% human serum and linear regression analysis, the 100% serum-adjusted mean ± standard deviation EC50 and EC90 values were extrapolated to 55.5 ± 5.5 and 214 ± 15 pM for samatasvir, respectively, and 73.1 ± 5.5 and 257 ± 22 pM for daclatasvir, respectively, suggesting that samatasvir retains antiviral activity in HCV-infected patients.

TABLE 4.

Anti-HCV activity in the presence of human serum binding proteinsa

| Compound | 10% FBS (EC50 [pM]) | 10% FBS + AAG |

40% HS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (pM) | Mean fold changeb | EC50 (pM) | Mean fold changeb | ||

| Samatasvir | 3.0 ± 0 | 6.0 ± 0 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 25.0 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 0.2 |

| Daclatasvir | 14.0 ± 3.0 | 119 ± 21.0 | 9.4 ± 1.1 | 33.5 ± 6.0 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

Values are the mean ± standard deviation of the results of 3 independent experiments.

A fold change was calculated for each experiment and a mean fold change ± standard deviation was calculated with these 3 values.

FIG 3.

Effect of human serum on the in vitro antiviral activity of samatasvir. Genotype 1b replicon cells were exposed to serial dilutions of samatasvir or the reference drug daclatasvir in increasing concentrations of human serum (10% to 50%). One hundred percent serum-adjusted EC50s of 55.5 and 73.1 pM, respectively, were attained by linear regression analysis. Each data point was derived from the mean of the results from three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviations.

Samatasvir retains activity in combination with other antiviral agents.

The effective use of HCV therapeutics will involve the use of multiple compounds, and as such, it is important to determine the effects of those combinations in vitro. Samatasvir was combined with representative HCV drugs in genotype 1b (GT1b) replicon cells to assess their impact on samatasvir antiviral activity. In the HCV replicon luciferase assay, MacSynergy II (Bliss independence model) and CombiTool (Loewe additivity model) determined the interaction of samatasvir with other drug classes to be additive. CalcuSyn showed a moderate antagonistic effect when samatasvir was used in combination with boceprevir or telaprevir, a mild antagonistic effect when samatasvir was used in combination with ribavirin, and a mild synergistic effect when samatasvir was used in combination with interferon (Table 5). It is not uncommon to reach discordant conclusions by different analytical tools (21). A number of factors may impact the outcomes from different analyses, including the shapes of the dose-response curves for individual agents, the range of drug concentrations tested, statistical thresholds, and the permissible data points to different tools. The cause of the discrepancy observed between MacSynergy/CombiTool and CalcuSyn in this study, therefore, may lie in the underlying models and features embedded in these analytical software applications. Overall, two of the three analyses support an additive interaction between samatasvir and other drug classes. No evidence of in vitro cytotoxicity was observed in cells treated with samatasvir and other drug classes alone or in combination, suggesting that the combined activity relationship is due to the inhibition of HCV replication rather than to cytotoxic effects.

TABLE 5.

Samatasvir used in combination with other drug classes in the replicon

| Compound added to samatasvir | No. of independent expts | Drug classa | Combination model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bliss independence | Loewe additivity | Combination index | |||

| Interferon alfa | 7 | Additive | Additive | Mild synergy | |

| Ribavirin | 7 | Additive-to-weak antagonism | Additive | Mild antagonism | |

| IDX184 | 7 | NI | Additive | Additive | Additive |

| TMC647055 | 8 | NNI | Additive | Additive | Additive |

| Telaprevir | 6 | PI | Additive | Additive | Moderate antagonism |

| Boceprevir | 6 | PI | Additive | Additive | Moderate antagonism |

| Simeprevir | 8 | PI | Additive | Additive | Additive |

NI, nucleoside inhibitor; NNI, nonnucleoside inhibitor; PI; protease inhibitor.

With an increasing number of drugs available to treat chronic HBV and HIV infections, the potential for drug interactions increases in a coinfected patient. Thus, the activity of samatasvir in the presence of clinically relevant concentrations of common HBV or HIV therapeutic agents was evaluated in the presence of 45% human serum. The concentrations tested were well above the measured EC50s, and no cytotoxicity was observed when samatasvir was combined with these drugs. The mean EC50 for samatasvir was 25 pM when tested alone and ranged from 23 to 45 pM in combination with 5× Cmax equivalent concentrations of the anti-HIV or anti-HBV agents, with fold change values of <2 (Table 6). Therefore, neither the anti-HBV nor anti-HIV drugs tested affected the activity of samatasvir in vitro.

TABLE 6.

Anti-HCV efficacy of samatasvir in combination with common anti-HIV or anti-HBV agentsa

| Drug | Target virus(es) (drug class)b | Mean HCV replicon EC50 ± SDc |

Samatasvir fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone (μM) | With samatasvir (pM)d | |||

| Kaletra | HIV (PI) | ≥114 | 45 ± 8 | 1.9 |

| Zidovudine | HIV (NRTI) | 85.7 | 28 ± 16 | 1.1 |

| Efavirenz | HIV (NNRTI) | ≥172 | 31 ± 8 | 1.3 |

| Raltegravir | HIV (IN) | >143 | 23 ± 6 | 0.9 |

| Lamivudine | HIV, HBV (NRTI) | >241 | 26 ± 6 | 1.0 |

| Tenofovir | HIV, HBV (NRTI) | >237 | 23 ± 6 | 0.9 |

| Telbivudine | HBV (NRTI) | >220 | 28 ± 2 | 1.1 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

PI, protease inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; IN, integrase inhibitor.

n = 3.

The EC50 for samatasvir in the presence of 45% human serum was 25 pM.

Samatasvir is not toxic to human liver or nonliver cell lines.

The cytotoxic effects of samatasvir in a human liver cell line (HepG2) were evaluated with a multiparameter cytotoxicity assay kit that monitors 4 cytotoxic endpoints in the same cell population: (i) extracellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDHe) measures the release of cytoplasmic lactate dehydrogenase into the cell culture supernatant upon membrane damage or cell lysis, (ii) glucose consumption in treated versus untreated cells is indicative of the overall physiological state, (iii) XTT is a variation of the commonly used MTS-based cell viability assay, and (iv) acid phosphatase (PAC) is a membrane-associated hydrolase residing in the cellular Golgi apparatus and is a marker for lysosomal activity. No measurable in vitro cytotoxicity of samatasvir was observed after 3 days of treatment up to 100 μM; the mean CC50 values were >100 μM across all four assays (Table 7). Daclatasvir was moderately cytotoxic in HepG2 cells, with mean CC50 values of 14.9 to 17.7 μM.

TABLE 7.

In vitro cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells after 3 days of treatment

| Compound | Mean CC50 ± SD (μM) fora: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDHe | Glucose | XTT | PAC | |

| Samatasvir | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Daclatasvir | 17.4 ± 0.3 | 14.9 ± 3.7 | 17.7 ± 3.1 | 17.6 ± 1.6 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.26 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

n = 3. Cytotoxicity endpoints were membrane permeability for LDH3, physiological cell state for glucose, mitochondrial metabolism for XTT, and lysosomal activity for PAC.

The long-term effects of samatasvir were evaluated in the immortalized hepatic cell line HepaRG, which retains many characteristics of primary hepatocytes (32). HepaRG cells terminally differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells and express various liver-specific functions, including major cytochrome P450 enzymes. This cell line provides a novel in vitro tool for cytotoxicity studies (33). Diclofenac, a positive control of liver toxicity, exhibited characteristic concentration-dependent cytotoxicity, with a mean ± standard deviation CC50 of 175.8 ± 14.2 μM, which is consistent with published results (34). Daclatasvir also showed concentration-dependent cytotoxicity in HepaRG cells, with a mean CC50 value of 23.7 μM. In contrast, no measurable in vitro cytotoxicity of samatasvir was observed in these cells after 14 days of treatment at concentrations up to 100 μM (Table 3).

The off-target activity of samatasvir was evaluated in a panel of five commonly used human cell lines derived from renal, central nervous system, blood, skeletal muscle, and colon tumors. As in the Zluc replicon-bearing hepatic cells (CC50, >100 μM), no in vitro cytotoxicity was apparent in any of the nonhepatic cell lines at the highest test concentration tested (50 μM) after 3 days of samatasvir exposure (Table 3). As in the hepatic lines, daclatasvir was moderately toxic to all five nonhepatic cell lines, with CC50 values ranging from 10.5 to 25.5 μM.

Samatasvir resistance loci are limited to NS5A.

As more genotype 1a- than 1b-infected subjects treated with daclatasvir monotherapy exhibited viral breakthrough due to the selection of resistant variants (35, 36), we selected genotype 1a replicon-bearing cells to determine the viral target of replicon inhibition by samatasvir and its resistance selection profile. A genotype 1a replicon cell line was cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of samatasvir for 90 days, while untreated cells were cultured in parallel. Selection began at 2× the EC50 and increased in 2-fold increments to a final concentration of 256× the EC50. At the end of selection, each samatasvir-treated cell line (719R-A, 719R-B, and 719R-C) exhibited high resistance to samatasvir in the replicon activity assays (1,100- to 3,100-fold change). These cell lines were also highly resistant to daclatasvir (630- to 2,200-fold change) but remained sensitive to the nucleotide polymerase inhibitor IDX184 (0.81- to 1.6-fold change), suggesting that samatasvir may target NS5A (Table 8).

TABLE 8.

Extent of resistance in samatasvir-selected genotype 1a replicon cell lines

| Cell line | Mean fold change ± SD witha: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Samatasvir | Daclatasvir | IDX184 | |

| 719R-A | 3,100 ± 1,500 | 1,700 ± 500 | 0.81 ± 0.24 |

| 719R-B | 1,100 ± 200 | 630 ± 80 | 0.93 ± 0.19 |

| 719R-C | 1,300 ± 400 | 2,200 ± 1,900 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

Mean fold changes ± standard deviations are for the mean results from three independent experiments for each samatasvir-selected cell line compared to their matched untreated control cell line.

Population sequencing across the entire coding sequence of the replicon was performed at the end of samatasvir selection. Dominant or minor substitutions appeared at 12 loci throughout the replicon in at least one of the samatasvir-selected cell lines (Table 9). Four minor substitutions (Y413H, L419P, and E420K in NS5A and F574S in NS5B) were detected in only one samatasvir-selected cell line. NS3 H593R was detected as a minor substitution in an untreated and a single samatasvir-selected cell line. NS3 D518N was selected as a dominant or minor substitution in each of the samatasvir-selected or untreated control cell lines. The low frequency of emergence and/or detection of these substitutions in the untreated cell lines suggests these were either random mutations unrelated to samatasvir exposure or adaptive mutations acquired to enhance the replicon replication.

TABLE 9.

Amino acid substitutions identified by population sequencing of untreated or samatasvir-selected genotype 1a replicon cellsa

| Region | Substitution | 719R-A | Untreated control A | 719R-B | Untreated control B | 719R-C | Untreated control C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS3 | T260A | Dominant | Minor | Minor | Dominant | ||

| D518N | Dominant | Dominant | Minor | Minor | Dominant | Minor | |

| H593R | Minor | Minor | |||||

| NS4B | E15G | Dominant | Minor | Dominant | Minor | Dominant | Minor |

| NS5A | Y93H | Dominant | Dominant | Dominant | |||

| E295G | Dominant | Minor | Dominant | ||||

| R318W | Minor | Minor | Dominant | ||||

| C404W | Minor | Minor | Minor | ||||

| Y413H | Minor | ||||||

| L419P | Minor | ||||||

| E420K | Minor | ||||||

| NS5B | F574S | Minor |

The 719R-A/untreated control A, 719R-B/untreated control B, and 719R-C/untreated control C cell lines represent three independent experiments.

NS3 T260A and NS4B E15G were observed as minor variants in the untreated cell lines but emerged as dominant variants in samatasvir-selected cells (Table 9). Site-directed mutant replicons bearing these individual substitutions significantly increased the replication capacity of the replicon; however, their susceptibility to samatasvir was comparable to that of the wild-type replicon. The NS3 T260A and NS4B E15G variants do not contribute to samatasvir resistance but may confer a replicative/adaptive advantage (Table 10).

TABLE 10.

Activity of samatasvir against genotype 1a replicons bearing amino acid substitutions in NS3, NS4B, and NS5A

| Region | Substitution | Mean fold change ± SD witha: |

Replicative capacity (% of WT ± SD)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samatasvir | Daclatasvir | IDX184 | |||

| NS3 | T260A | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 300 ± 140 |

| NS4B | E15G | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 264 ± 18 |

| NS5A | K24E | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 79 ± 25 |

| M28T | 150 ± 10 | 170 ± 20 | 1.06 ± 0.14 | 66 ± 7 | |

| Q30E | 420 ± 80 | 2,900 ± 400 | 1.11 ± 0.14 | 119 ± 7 | |

| Q30H | 24 ± 2 | 150 ± 30 | 1.07 ± 0.10 | 100 ± 2 | |

| Q30K | 310 ± 100 | 750 ± 190 | 0.89 ± 0.17 | 100 ± 14 | |

| Q30R | 10 ± 1 | 95 ± 22 | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 119 ± 7 | |

| L31F | 68 ± 14 | 43 ± 9 | 1.06 ± 0.31 | 85 ± 4 | |

| L31M | 310 ± 60 | 110 ± 30 | 1.04 ± 0.21 | 143 ± 32 | |

| L31V | 420 ± 80 | 900 ± 180 | 1.33 ± 0.10 | 210 ± 8 | |

| P32L | 170 ± 10 | 140 ± 20 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 16 ± 3 | |

| Y93C | 40 ± 5 | 290 ± 50 | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 92 ± 18 | |

| Y93H | 4,400 ± 900 | 1,400 ± 500 | 1.05 ± 0.25 | 43 ± 4 | |

| Y93N | 14,000 ± 3,000 | 7,800 ± 3,500 | 1.01 ± 0.25 | 60 ± 6 | |

| E295G | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 132 ± 36 | |

| R318W (GT 1a)b | RDc | RD | RD | 1.8 ± 0.8 | |

| R318W (GT 1b)d | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.23 | 79 ± 4 | |

n = 3. WT, wild type.

NS5A R318W substitution in the genotype 1a replicon.

RD, replication deficient.

NS5A R318W substitution in the genotype 1b replicon.

In NS5A, three dominant variants were observed (Y93H, E295G, and R318W), two of which (Y93H and R318W) were present in the samatasvir-selected cell lines but not in the control cell lines. NS5A E295G was present as a minor variant in one control cell line but became dominant in two samatasvir-treated cell lines. However, the activity of samatasvir against this substitution was similar to that in the wild type, indicating that this substitution does not confer resistance to samatasvir (Table 10). The R318W substitution dramatically reduced the fitness of the genotype 1a replicon to 1.8% of that of the wild type; the poor fitness of this replicon precluded measurement of an EC50 due to low luciferase signal; therefore, its contribution to samatasvir resistance was not determined in the genotype 1a replicon. In contrast, the R318W substitution in the genotype 1b replicon was replication competent (79% of the wild type) and was susceptible to samatasvir (Table 10).

NS5A Y93H is an amino acid substitution that has been shown to confer significant resistance to NS5A inhibitors (10, 37–40), and when introduced into the genotype 1a replicon, this substitution conferred a 4,400-fold shift in activity against samatasvir (Table 10). The emergence of Y93H was examined from RNA samples collected at each cell passage. As the concentration of samatasvir increased during selection, the Y93H substitution emerged as a dominant variant in all three cell lines at approximately 128× the EC50. None of the three cell lines produced any other dominant (>50% penetrance) or minor (25 to 50% penetrance) variant within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A over the course of selection (Table 9). An examination of the population sequences from the control cell lines showed no changes at Y93, suggesting that the observed changes in the samatasvir-treated cell lines were a consequence of selection pressure exerted by the drug. These data strongly suggest that NS5A is a viral target of samatasvir, with Y93H being the predominant resistance-associated variant identified following population sequencing of the genotype 1a replicon.

Samatasvir resistance loci within NS5A.

At the end of selection, the cell line 719R-A was chosen for further investigation by clonal sequencing of the genomic region encoding the first 100 amino acids of NS5A. All of the clones (100/100) selected from this cell line contained a substitution at one or more of the five loci M28, Q30, L31, P32, or Y93. In some clones, only a single substitution at one of these five loci was observed, suggesting that a single substitution might be sufficient to promote resistance to samatasvir. The clonal sequences obtained from the untreated control cell line A revealed only an M28I substitution at these loci, which was not identified in the 719R-A samatasvir-selected cell line; this suggests that M28I may be a random substitution. The absence of other substitutions at these loci in the control cell line suggests that the substitutions observed in the 719R-A cell line are the result of selection pressure from samatasvir.

Clonal sequencing of 719R-A confirmed that Y93 was the only locus with a dominant variant and the most highly mutated locus: 58/100 clonal sequences contained a mutation at the Y93 locus, with 51/58 encoding Y93H variants, 4/58 encoding Y93C, and 1/58 each of Y93R, Y93S, and Y93N (Table 11). Phenotypic analysis of some of these substitutions indicated that similar to daclatasvir, these substitutions conferred moderate to high levels of resistance in genotype 1 replicons (Table 10). Q30 was the second most highly mutated site (33/100) within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A after selection. Unlike the Y93 locus that tended to mutate toward a single variant (Y93H), the substitutions at Q30 were nearly evenly distributed among four variants: Q30E (n = 6), Q30H (n = 6), Q30K (n = 12), and Q30R (n = 9) (Table 11). Substitutions at this locus conferred moderate to high levels of resistance to samatasvir and high levels of resistance to daclatasvir in genotype 1a replicons (Table 10). Interestingly, the genotype 1b NS5A R30E substitution was not resistant to samatasvir (Table 12). K24 was the third most highly mutated residue observed by clonal sequencing of the selected cell line (17/100). As with the Q30 locus, the substitutions at K24 were distributed among numerous variants: K24E (n = 7), K24Q (n = 3), K24R (n = 3), K24T (n = 3), and K24I (n = 1) (Table 11); however, K24E did not confer resistance to samatasvir or daclatasvir (Table 10). This, together with the fact that the substitutions at K24 were always linked with at least one additional substitution shown to confer resistance to samatasvir (M28, Q30, or Y93 locus), suggests that the K24 locus may not confer resistance to samatasvir. Since the K24E substitution does not confer a replicative advantage (79% of the wild type), the contribution of this substitution to samatasvir resistance is unclear.

TABLE 11.

NS5A variants identified in the samatasvir-selected 719R-A cell linea

| Locus | Residue | % penetrance |

|---|---|---|

| K20 | M | 1 |

| N | 1 | |

| T | 6 | |

| K24b | E | 7 |

| I | 1 | |

| Q | 3 | |

| R | 3 | |

| T | 3 | |

| M28 | T | 7 |

| Q30 | E | 6 |

| H | 6 | |

| K | 12 | |

| R | 9 | |

| L31 | M | 8 |

| P | 1 | |

| P32 | L | 4 |

| Y93 | C | 4 |

| H | 51 | |

| N | 1 | |

| R | 1 | |

| S | 1 |

Only variants with significance to samatasvir resistance are displayed.

All variants at K24 were linked to a substitution at either M28, Q30, or Y93.

TABLE 12.

Activity of samatasvir against genotype 1b and 2a replicons bearing amino acid substitutions in NS5A

| Substitution | Genotype | Mean fold change ± SDa |

Replicative capacity (% of WT ± SD)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samatasvir | Daclatasvir | IDX184 | |||

| L28T | 1b | 74 ± 7 | 25 ± 4 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 3 ± 1 |

| R30E | 1b | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 17 ± 5 |

| L31F | 1b | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 0.88 ± 0.09 | 90 ± 15 |

| L31M | 1b | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.91 ± 0.20 | 86 ± 7 |

| L31M | 2a | 90 ± 16 | NDb | ND | 69 ± 19 |

| L31V | 1b | 15 ± 2 | 23 ± 7 | 0.92 ± 0.22 | 61 ± 10 |

| P32L | 1b | 6.7 ± 3.7 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | 0.66 ± 0.14 | 12 ± 6 |

| Y93C | 1b | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 33 ± 8 |

| Y93H | 1b | 93 ± 22 | 21 ± 3 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 25 ± 5 |

| Y93N | 1b | 160 ± 30 | 35 ± 5 | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 23 ± 6 |

n = 3.

ND, not done.

The two other loci identified with NS5A variants in the 719R-A cell line at some point during selection were M28 and L31. By clonal sequencing, these loci show M28T (n = 7), L31M (n = 8), and L31P (n = 1) substitutions (Table 11). M28T and L31M were shown to confer high levels of resistance to samatasvir and daclatasvir (Table 10). The orthologous substitutions in genotype 1b, L28T and L31M, conferred moderate and low resistance, respectively (Table 12). No single substitution at the K24, M28, Q30, and L31 loci appeared in >12 clones, but together, substitutions at these loci accounted for 66 of the 189 variants observed in the 100 clones from 719R-A. Ninety-six of the 100 clones contained at least one mutation at the dominant variant locus Y93 or at one of the minor variant sites: K24, M28, Q30, or L31. The remaining clones (4/100) encoded a single P32L substitution, which conferred a high level of resistance to samatasvir (Table 10). Mutations in the K20 locus were identified in eight out of 100 clones, with 6/8 mutations encoding the K20T substitution. Because of the low penetrance of mutations at this site and the observation that all substitutions at K20 were accompanied by substitutions at other loci, K20 was not considered a primary resistance locus. Two genotype 1a substitutions reported in the literature but not observed in our resistance selection experiments conferred moderate (L31F; 68-fold) or high (L31V; 420-fold) resistance to samatasvir (Table 10) (37).

The resistance profile of samatasvir was further determined in genotype 1b and 2a replicons bearing substitutions reported to confer resistance to the NS5A inhibitor class (Table 12) (37, 41) (X. J. Zhou, B. Vince, J. Hill, E. Lawitz, W. O'Riordan, L. Webster, D. Gruener, R. S. Mofsen, A. Murillo, E. Donovan, J. Chen, J. Z. Sullivan-Bólyai, and D. Mayers, presented at the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, Suntec City, Singapore, 7 to 10 March 2013). Substitutions at the L31 locus, as mentioned above, conferred 68- to 420-fold changes in genotype 1a but only 3.6- to 15-fold changes in genotype 1b. The genotype 2a L31M polymorphism confers approximately 90-fold resistance to samatasvir, in agreement with clinical results demonstrating a reduced response to samatasvir in HCV genotype 2a-infected subjects bearing the NS5A M31 polymorphism (42; Zhou et al.). The genotype 1a P32L substitution showed a 170-fold change in resistance, but in the context of genotype 1b, the change was only 6.7-fold. At the Y93 locus, resistance ranged from 40- to 14,000-fold change with genotype 1a variants but 2.7- to 160-fold change in the genotype 1b replicon. Similar to previous studies, NS5A substitutions in the genotype 1a replicon generally conferred higher resistance to samatasvir than those in the genotype 1b replicon (37, 38, 42).

Samatasvir is not cross-resistant with protease or polymerase inhibitors.

The activity of samatasvir against substitutions known to confer resistance to different classes of HCV inhibitors was evaluated. Three NS3 substitutions (R155K, A156T, and D168V) and four NS5B substitutions (S282T, C316Y, M414T, and M423T) that confer resistance to protease or polymerase inhibitors, respectively, were tested (43–45) (J. P. Bilello, M. La Colla, I. Serra, J. M. Gillum, M. A. Soubasakos, C. Chapron, B. Li, A. Bonin, R. J. Panzo, L. B. Lallos, M. Seifer, and D. N. Standring, presented at the 16th International Symposium on Hepatitis C Virus and Related Viruses, Nice, France, 3 to 7 October 2009). Samatasvir exhibited similar activity against replicons bearing these resistance variants and the wild-type replicon, indicating that samatasvir is not cross-resistant with protease, nucleoside, or nonnucleoside inhibitors (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The current study evaluated the in vitro activity, cytotoxicity, and resistance profiles of samatasvir, a novel NS5A inhibitor of HCV replication. As the in vitro activity of the initial NS5A inhibitors of replication varied significantly across HCV genotypes, our efforts were directed toward designing a pangenotypic NS5A replication inhibitor with a narrow range of activity among the genotypes. To assess this, we examined the activity of samatasvir against intergenotypic genotype 1b replicons bearing either the first 100 amino acids or the full-length NS5A region from the orthologous regions of genotypes 1 to 5. The in vitro activity of samatasvir is consistent among all genotypes examined, with EC50s ranging from 2 to 24 pM, which distinguishes it from other NS5A inhibitors, whose activity is reduced in genotypes beyond genotype 1b (8, 46). Furthermore, the in vitro activity of samatasvir against HCV replicons was only mildly affected by human serum, such as AAG, and it was not reduced in the presence of commonly prescribed HBV or HIV antivirals. Samatasvir was effectively combined with other classes of direct-acting HCV antivirals, as well as interferon alfa (IFN-α) and ribavirin, demonstrating its suitability as part of a combination treatment regimen in the clinical setting. Samatasvir was selective for HCV and was not active against other DNA and RNA viruses. Furthermore, samatasvir showed no evidence of in vitro cytotoxicity in an extensive panel of cell lines, affording a selectivity index of >5 × 107.

Since NS5A does not have an enzymatic function, and a direct assay to measure its inhibition is not available, we relied on indirect methods to verify the molecular target of inhibition by samatasvir. The only amino acid substitutions arising in selection experiments with samatasvir that were shown to confer resistance to samatasvir were within NS5A, which suggests that samatasvir inhibits the function(s) of NS5A.

Resistance selection with samatasvir generated a spectrum of variants in the genotype 1a replicon system within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A, in concordance with previous results with daclatasvir (8, 37, 47). The wide distribution of resistance variants within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A precluded their detection by population sequencing because no single mutation achieved sufficient penetrance. The lone exception to this general observation was the Y93 locus, for which the Y93H resistance substitution was clearly identified by population sequencing in all three samatasvir-resistant cell lines. NS5A Y93H was identified in 51 of the 100 clonal sequences from the 719R-A resistant cell line. The Y93H substitution conferred 4,400-fold resistance to samatasvir when tested as a site-directed mutant in the genotype 1a replicon. An additional seven clonal sequences, representing four other variants, were detected at the Y93 locus in the 719R-A resistant cell line. Thus, mutations at the Y93 locus were the predominant mutations detected following selection with samatasvir in the genotype 1a replicon.

Besides the Y93 locus, no other minor or dominant mutations within the genomic region encoding the first 100 amino acids of NS5A were identified by population sequencing. However, clonal sequencing analysis revealed a more nuanced resistance profile for samatasvir. All clonal sequences examined from the 719R-A resistant cell line encoded at least one substitution at one of the following five loci: M28, Q30, L31, P32, or Y93. The P32L substitution was observed infrequently and was not linked with any other substitution among the clonal sequences examined. Substitutions at the other four loci were observed as either single or linked substitutions within the region examined. Whether a substitution was observed to occur alone or linked to another was determined at least in part by the degree of resistance conferred by the amino acid substitution. The second most mutated locus following samatasvir selection was at position Q30, distributed among four variants. The Q30E substitution, which conferred 420-fold resistance to samatasvir, was not observed to be linked to any other substitution within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A. In contrast, the Q30H substitution conferred only 24-fold resistance to samatasvir and was always found to be linked to a substitution at the Y93 locus. The Q30K substitution (310-fold change in EC50) was sometimes observed as the sole substitution within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A, and at other times, it was linked to another substitution. However, no Q30K substitution was seen linked to a mutation at Y93 in any clonal sequence. Thus, a possible correlation exists between the degree of resistance conferred by a substitution at Q30 and whether the substitution was observed to occur alone or linked to another substitution.

Unlike substitutions at M28, Q30, L31, or Y93, which were found both linked and not linked to another substitution, the K24 substitutions were always linked to another substitution within the first 100 amino acids of NS5A. The K24 substitutions were distributed among five different variants (K24E, K24I, K24Q, K24R, and K24T), with the K24E substitution being the most frequent, and they were always linked with another substitution at one or more of the M28, Q30, and Y93 loci. The K24E substitution, which did not confer resistance to samatasvir by itself, was never accompanied by a substitution at Y93 but was always linked to a substitution at Q30. A possible explanation for the emergence of K24E is that it functions as a compensatory substitution to restore replicon fitness. Yet, all genotype 1a mutant replicons containing K24E-linked substitutions at the Q30 locus demonstrated fitness at least as robust as that of the wild-type replicon. The benefit of substitutions at the K24 locus to the replicon when treated with samatasvir remains unclear.

Four dominant amino acid substitutions outside the first 100 amino acid region of NS5A were identified by population sequencing of the replicons from samatasvir-resistant cell lines. These included NS5A E295G and R318W, NS3 T260A, and NS4B E15G. These substitutions were either replication deficient or did not confer resistance to samatasvir when examined individually in the genotype 1a replicon. Thus, all substitutions that conferred resistance to samatasvir were found within the first 100 amino acids of the NS5A protein.

Genotype 1a substitutions generally conferred higher levels of resistance to samatasvir in cell culture, which correlates with both in vitro and clinical observations of other NS5A inhibitors of HCV replication (35–38). Consistent with the in vitro resistance profile for samatasvir presented here, the most common treatment-emergent variants observed following 3-day monotherapy with samatasvir in the clinic were at the NS5A M28, L31, and Y93 loci (48). However, as samatasvir is not cross-resistant to other classes of direct-acting antivirals in vitro, clinical resistance is expected to be controlled by combination therapy.

In clinical studies, samatasvir was initially evaluated at doses of 1 to 100 mg daily for up to 7 days in healthy volunteers and 3 days in HCV-infected subjects. The pharmacokinetics was dose proportional, with a terminal half-life of approximately 24 h, supporting once-a-day dosing. Following 3 daily doses of 25 to 100 mg samatasvir, viral load reductions of up to 4 log10 were observed in subjects with HCV genotypes 1 through 4. A reduced antiviral response was observed in HCV genotype 2-infected subjects who had the NS5A M31 polymorphism at baseline. Currently, HCV-infected patients with genotype 1 or 4 are being treated with combination regimens, including the FDA-approved protease inhibitor simeprevir and samatasvir, for 12 weeks. Samatasvir has been generally safe and well tolerated in all clinical trials to date. For the daily all-oral regimen containing 150 mg simeprevir, 50 mg samatasvir, and weight-based ribavirin, the sustained viral response rate at 4 weeks posttreatment (SVR4) was 85% (42; Zhou et al.).

The low-picomolar multigenotypic activity of samatasvir in vitro has been confirmed clinically in patients infected with HCV genotypes 1 through 4 (42; Zhou et al.). The lack of cross-resistance to other classes of HCV direct-acting antivirals and additive direct-acting antiviral combination data in vitro support the ongoing phase II studies of samatasvir as part of all-oral interferon-free direct-acting antiviral regimens for the treatment of HCV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The MAGI-CCR5 cell line was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, and HeLa-CD4-LTR-β-gal was obtained from Julie Overbaugh.

We thank Idenix personnel Bianca Heinrich and Alice Blouet for examining the activity of samatasvir against the R318W substitution in the genotype 1b replicon, and we thank Teresa Dahlman for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke KP, Cox AL. 2010. Hepatitis C virus evasion of adaptive immune responses: a model for viral persistence. Immunol. Res. 47:216–227. 10.1007/s12026-009-8152-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2011. Incivek (telaprevir) package insert. Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/201917lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeuzem S, Berg T, Moeller B, Hinrichsen H, Mauss S, Wedemeyer H, Sarrazin C, Hueppe D, Zehnter E, Manns MP. 2009. Expert opinion on the treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Viral Hepat. 16:75–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01012.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange CM, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. 2010. Review article: specifically targeted anti-viral therapy for hepatitis C–a new era in therapy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 32:14–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilead Sciences, Inc. 2013. Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) package insert. Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, CA: http://www.gilead.com/∼/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/sovaldi/sovaldi_pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penin F, Dubuisson J, Rey FA, Moradpour D, Pawlotsky JM. 2004. Structural biology of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 39:5–19. 10.1002/hep.20032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Y, Staschke KA, Tan SL. 2006. HCV NS5A: a multifunctional regulator of cellular pathways and virus replication, p 267–229 In Tan SL. (ed), Hepatitis C virus: genomes and molecular biology. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, Serrano-Wu MH, Langley DR, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, Jr, Lemm JA, Wang C, Knipe JO, Chien C, Colonno RJ, Grasela DM, Meanwell NA, Hamann LG. 2010. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature 465:96–100. 10.1038/nature08960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang PL, Gao M, Lin K, Liu Q, Villareal VA. 2011. Anti-HCV drugs in the pipeline. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1:607–616. 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawitz EJ, Gruener D, Hill JM, Marbury T, Moorehead L, Mathias A, Cheng G, Link JO, Wong KA, Mo H, McHutchison JG, Brainard DM. 2012. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, 3-day, dose-ranging study of GS-5885, an NS5A inhibitor, in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C. J. Hepatol. 57:24–31. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merck and Co., Inc. 2007. Isentress (raltegravir) package insert. Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Whitehouse Station, NJ: http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/i/isentress/isentress_pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Kräusslich HG, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796. 10.1038/nm1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299. 10.1073/pnas.0503596102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chackerian B, Long EM, Luciw PA, Overbaugh J. 1997. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors participate in postentry stages in the virus replication cycle and function in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 71:3932–3939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakabayashi H, Taketa K, Miyano K, Yamane T, Sato J. 1982. Growth of human hepatoma cell lines with differentiated functions in chemically defined medium. Cancer Res. 42:3858–3863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Q, Guo JT, Seeger C. 2003. Replication of hepatitis C virus subgenomes in nonhepatic epithelial and mouse hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 77:9204–9210. 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9204-9210.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckwold VE, Wilson RJH, Nalca A, Beer BB, Voss TG, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, III, Wei J, Wenzel-Mathers M, Walton EV, Smith RJ, Pannansch M, Ward P, Wells J, Chuvala L, Sloane S, Paulman R, Russell J, Hartman T, Ptak R. 2004. Antiviral activity of hop constituents against a series of DNA and RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 61:57–62. 10.1016/S0166-3542(03)00155-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prichard MN, Prichard LE, Shipman C., Jr 1993. Strategic design and three-dimensional analysis of antiviral drug combinations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:540–545. 10.1128/AAC.37.3.540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaney WE, IV, Yang H, Miller MD, Gibbs CS, Xiong S. 2004. Combinations of adefovir with nucleoside analogs produce additive antiviral effects against hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3702–3710. 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3702-3710.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dressler V, Müller G, Sühnel J. 1999. CombiTool–a new computer program for analyzing combination experiments with biologically active agents. Comput. Biomed. Res. 32:145–160. 10.1006/cbmr.1999.1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng JY, Ly JK, Myrick F, Goodman D, White KL, Svarovskaia ES, Borroto-Esoda K, Miller MD. 2009. The triple combination of tenofovir, emtricitabine and efavirenz shows synergistic anti-HIV-1 activity in vitro: a mechanism of action study. Retrovirology 6:44–59. 10.1186/1742-4690-6-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou TC, Talalay P. 1984. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 22:27–55. 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AbbVie, Inc. 2000. Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) package insert. AbbVie, Inc., North Chicago, IL: http://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/kaletratabpi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. 1998. Sustiva (efavirenz) package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ: http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_sustiva.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilead Sciences, Inc. 2001. Viread (tenofovir) package insert. Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, CA: http://www.gilead.com/∼/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/viread/viread_pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.GlaxoSmithKline. 1995. Epivir-HBV (lamivudine) package insert. GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_epivir_hbv.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.GlaxoSmithKline. 1987. Retrovir (zidovudine) package insert. GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/019910s033lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. 2006. Tyzeka (telbivudine) package insert. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/cs/www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/tyzeka.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Hoff M, Moorman A, Lamers W. 1992. Electroporation in ‘intracellular' buffer increases cell survival. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:2902. 10.1093/nar/20.11.2902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molla A, Vasavanonda S, Kumar G, Sham HL, Johnson M, Grabowski B, Denissen JF, Kohlbrenner W, Plattner JJ, Leonard JM, Norbeck DW, Kempf DJ. 1998. Human serum attenuates the activity of protease inhibitors toward wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus. Virology 250:255–262. 10.1006/viro.1998.9383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benet LZ, Hoener BA. 2002. Changes in plasma protein binding have little clinical relevance. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 71:115–121. 10.1067/mcp.2002.121829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, Guyomard C, Lucas J, Trepo C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. 2002. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:15655–15660. 10.1073/pnas.232137699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jossé RM, Aninat C, Glaise D, Dumont J, Fessard V, Morel F, Poul JM, Guguen-Guillouza C, Guillouza A. 2008. Long-term functional stability of human HepaRG hepatocytes and use for chronic toxicity and genotoxicity studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36:1111–1118. 10.1124/dmd.107.019901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bort R, Ponsoda X, Jover R, Gómez-Lechón MJ, Castell JV. 1998. Diclofenac toxicity to hepatocytes: a role for drug metabolism in cell toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 288:65–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nettles RE, Gao M, Bifano M, Chung E, Persson A, Marbury TC, Goldwater R, DeMicco MP, Rodriguez-Torres M, Vutikullird A, Fuentes E, Lawitz E, Lopez-Talavera JC, Grasela DM. 2011. Multiple ascending dose study of BMS-790052, a nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor, in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Hepatology 54:1956–1965. 10.1002/hep.24609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, Jr, Nower P, Valera L, Roberts S, Fridell RA, Gao M. 2013. Persistence of resistant variants in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with the NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2054–2065. 10.1128/AAC.02494-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fridell R, Qiu D, Wang C, Valera L, Gao M. 2010. Resistance analysis of the hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor BMS-790052 in an in vitro replicon system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3641–3650. 10.1128/AAC.00556-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fridell RA, Wang C, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, Jr, Nower P, Valera L, Qiu D, Roberts S, Huang X, Kienzle B, Bifano M, Nettles RE, Gao M. 2011. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of variants resistant to hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor BMS-790052 in humans: in vitro and in vivo correlations. Hepatology 54:1924–1935. 10.1002/hep.24594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin HM, Wang JC, Hu HS, Wu PS, Yang CC, Wu CP, Pu SY, Hsu TA, Jiaang WT, Chao YS, Chern JH, Yeh TK, Yueh A. 2011. Resistance analysis and characterization of a thiazole analogue, BP008, as a potent hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:44–53. 10.1128/AAC.00599-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin HM, Wang JC, Hu HS, Wu PS, Wang WH, Wu SY, Yang CC, Yeh TK, Hsu TA, Jiaang WT, Chao YS, Chern JH, Yueh A. 2012. Resistance studies of a dithiazol analogue, DBPR110, as a potential hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor in replicon systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:723–733. 10.1128/AAC.01403-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vince B, Hill JM, Lawitz EJ, O'Riordan W, Webster LR, Gruener DM, Mofsen RS, Murillo A, Donovan E, Chen J, McCarville JF, Sullivan-Bólyai JZ, Mayers D, Zhou XJ. 2014. A randomized, double-blind, multiple-dose study of the pan-genotypic NS5A inhibitor samatasvir in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 2, 3 or 4. J. Hepatol. 60:920–927. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu R, Kong R, Mann P, Ingravallo P, Zhai Y, Xia E, Meinke P, Olsen D, Ludmerer S, Kozlowski J, Coburn C. 2012. In vitro resistance analysis of HCV NS5A inhibitor: MK-8742 demonstrates increased potency against clinical resistance variants and higher resistance profile. J. Hepatol. 56(Suppl 2):S334–S335. 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60870-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lallos LB, Bilello JP, Soubasakos MA, Gillum J, La Colla M, Serra I, Luizzi M, McCarville J, Seifer M, Good SS, Larsson M, Selden J, Parsy C, Surleraux D, Standring DN. 2009. Preclinical profiles of IDX136 and IDX316, two novel macrocyclic HCV protease inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 50(Suppl 1):S132. 10.1016/S0168-8278(09)60346-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cretton-Scott E, Perigaud C, Peyrottes S, Licklider L, Camire M, Larsson M, La Colla M, Hildebrand E, Lallos LB, Bilello JP, McCarville J, Seifer M, Liuzzi M, Pierra C, Badaroux E, Gosselin G, Surleraux D, Standring DN. 2008. In vitro antiviral activity and pharmacology of IDX184, a novel and potent inhibitor of HCV replication. J. Hepatol. 48(Suppl 2):S220. 10.1016/S0168-8278(08)60590-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicolas O, Boivin I, St-Denis C, Bedard J. 2008. Genotypic analysis of HCV NS5B variants selected from patients treated with VCH-759. J. Hepatol. 48(Suppl 2):S317. 10.1016/S0168-8278(08)60846-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng G, Peng B, Corsa A, Yu M, Nash M, Lee YJ, Xu Y, Kirschberg T, Tian Y, Taylor J, Link J, Delaney W., IV 2012. Antiviral activity and resistance profile of the novel HCV NS5A inhibitor GS-5885. J. Hepatol. 56(Suppl 2):S464. 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)61184-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C, Huang H, Valera L, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, Jr, Nower PT, Jia L, Qiu D, Huang X, Altaf A, Gao M, Fridell RA. 2012. Hepatitis C virus RNA elimination and development of resistance in replicon cells treated with BMS-790052. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1350–1358. 10.1128/AAC.05977-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarville J, Seifer M, Standring D, Mayers D. 2013. Treatment-emergent variants following 3 days of monotherapy with IDX719, a potent, pan-genotypic NS5A inhibitor, in subjects infected with HCV genotypes 1–4. J. Hepatol. 58(Suppl 1):S491–S492. 10.1016/S0168-8278(13)61210-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]