Abstract

A W153L substitution in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) was recently identified by selection with a novel nucleotide-competing RT inhibitor (NcRTI) termed compound A that is a member of the benzo[4,5]furo[3,2,d]pyrimidin-2-one NcRTI family of drugs. To investigate the impact of W153L, alone or in combination with the clinically relevant RT resistance substitutions K65R (change of Lys to Arg at position 65), M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, on HIV-1 phenotypic susceptibility, viral replication, and RT enzymatic function, we generated recombinant RT enzymes and viruses containing each of these substitutions or various combinations of them. We found that W153L-containing viruses were impaired in viral replicative capacity and were hypersusceptible to tenofovir (TFV) while retaining susceptibility to most nonnucleoside RT inhibitors. The nucleoside 3TC retained potency against W153L-containing viruses but not when the M184I substitution was also present. W153L was also able to reverse the effects of the K65R substitution on resistance to TFV, and K65R conferred hypersusceptibility to compound A. Biochemical assays demonstrated that W153L alone or in combination with K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C impaired enzyme processivity and polymerization efficiency but did not diminish RNase H activity, providing mechanistic insights into the low replicative fitness associated with these substitutions. We show that the mechanism of the TFV hypersusceptibility conferred by W153L is mainly due to increased efficiency of TFV-diphosphate incorporation. These results demonstrate that compound A and/or derivatives thereof have the potential to be important antiretroviral agents that may be combined with tenofovir to achieve synergistic results.

INTRODUCTION

Current standard anti-HIV-1 therapy, termed highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), consists of three or more antiretroviral compounds from six distinct classes, including nucleoside reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors (NRTIs), nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), fusion inhibitors, entry inhibitors, and integrase inhibitors (INIs) (for recent reviews, see references 1 and 2). HAART commonly includes two NRTIs in combination with either an NNRTI, a PI, or more recently, an INI (66). HAART has been effective at suppressing HIV-1 replication, partially reversing immunodeficiency, reducing HIV-1-associated complications, and prolonging life (3, 4). However, all antiretrovirals can be compromised by the development of drug resistance (5, 6) that arises from the rapid replication rate of HIV-1 and the error-prone nature of its RT (7, 8). In the absence of an effective vaccine against HIV-1 infection, it is important to develop novel effective antiretrovirals with superior resistance profiles.

There are currently 8 approved NRTIs that all compete with natural deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) substrates to act as DNA chain terminators. In contrast, NNRTIs act allosterically and noncompetitively by inducing conformational changes in RT. The mechanisms of NNRTI resistance are due to specific substitutions in RT that affect the entry of NNRTIs into the NNRTI binding pocket or decrease NNRTI binding by steric hindrance (6, 9, 10). Two major mechanisms account for resistance to NRTIs, discrimination and excision (for reviews, see references 11 and 12). Discrimination is based on the decreased incorporation of NRTIs by a mutated RT, whereas excision is based on the enhanced ability of a mutated RT to excise an incorporated chain termination inhibitor from the viral DNA terminus.

Recently, a novel class of HIV-1 RT inhibitors, termed nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NcRTIs), has been identified (13–17). The indolopyridone compound INDOPY-1 defines this class of compounds, which are not nucleotide analogues but, rather, act as nucleotide-competing inhibitors of RT. NcRTIs inhibit reverse transcription by binding to the RT active site in competition with the next incoming nucleotide to form dead-end complexes, a distinct mechanism. The potency of INDOPY-1 was mostly unaffected by substitutions associated with resistance against NNRTIs or NRTIs, although NRTI substitutions at positions M184V (change of Met to Val at position 184) and Y115F were shown to result in diminished susceptibility to INDOPY-1 (13, 15). A more potent novel benzo[4,5]furo[3,2,d]pyrimidin-2-one (BFPY) chemical series of NcRTIs, represented by compound A, was also identified that retains potency against RT containing M184V but selects for a novel W153L substitution in RT (21). W153L mutant viruses were shown to have diminished replication capacity and were highly resistant to compound A but sensitive to nevirapine (NVP) and hypersusceptible to abacavir (ABC), tenofovir (TFV), lamivudine (3TC), and emtricitabine (FTC) (17). This unique resistance profile makes it important to understand how the W153L substitution might affect drug susceptibly, enzyme function, and viral replication fitness when other common resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) are also present.

Here, we have investigated the effect of W153L, alone or in combination with the clinically relevant RT substitutions K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, andY181C, on drug susceptibility and viral replication capacity. We found that W153L impairs viral replication but does not affect susceptibility to most NNRTIs or to 3TC, except, for the latter, when M184I is also present. All of the W153L-containing viruses that were tested were hypersusceptible to TFV. We also studied relevant recombinant RT enzymes and found that the presence of W153L, alone or in combination with each of the RAMs K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, diminished both enzyme processivity and the efficiency of DNA polymerization as assessed in gel-based assays. However, none of these mutant RT enzymes diminished RNase H activity. We also investigated the underlying mechanism of the TFV hypersusceptibility conferred by W153L.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, cells, and nucleic acids.

Etravirine (ETR) and rilpivirine (RPV) were gifts from Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Titusville, NJ). TFV was kindly provided by Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA). 3TC was a gift from Glaxo-SmithKline (Greenford, United Kingdom). Efavirenz (EFV) and nevirapine (NVP) were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The NcRTI compound A was obtained from Boehringer Ingelheim Canada Ltd. (Laval, QC) (17).

The HEK293T cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The following reagents and cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program: the infectious molecular clone pNL4-3 was from Malcolm Martin, and the TZM-bl (JC53-bl) cell line from John C. Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu, Tranzyme, Inc.

The pNL4.3PFB plasmid DNA was a generous gift from Tomozumi Imamichi, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. The plasmid pRT6H-PROT was a generous gift from Stuart F. J. Le Grice, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

An HIV-1 RNA template, ∼500 nucleotides (nt) in size, spanning the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) to the primer binding site, was transcribed in vitro from AccI-linearized pHIV-PBS (primer-binding sequence) DNA (18) by using an Ambion T7-MEGAshortscript kit (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) as described previously (19). The oligonucleotides used in this study were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) and purified by polyacrylamide-urea gel electrophoresis. For 5′-end labeling of oligonucleotides with [γ32P]ATP, the Ambion KinaseMax kit was used, followed by purification through Ambion NucAway spin columns, according to protocols provided by the supplier (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada).

Site-directed mutagenesis and preparation of site-directed mutant HIV-1NL4-3 virus stocks.

To construct HIV-1 RT expression plasmids and recombinant HIV-1 strain NL4-3 (HIV-1NL4-3) infectious clones harboring desired substitutions in the RT gene, site-directed mutagenesis reactions were carried out using a Stratagene QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies Canada, Inc., Mississauga, ON). This work was performed with the HIV-1 RT expression plasmid DNA pbRT6H-PROT (19) and the pNL4.3PFB plasmid DNA (20) to generate recombinant RT enzymes and HIV-1NL4-3 viruses containing the desired RT substitutions. DNA sequencing was performed to verify the absence of spurious substitutions and the presence of any desired substitution in the RT-coding sequences. Recombinant HIV-1 wild-type (WT) and mutant viruses were generated by transfection of the corresponding proviral plasmid DNAs into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viral supernatants were harvested at 48 h posttransfection, centrifuged for 5 min at 800 × g to remove cellular debris, filtered through a 0.45-μM-pore-size filter, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. The levels of p24 antigen in viral supernatants were measured by using a Perkin-Elmer HIV-1 p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). BH10 (HIV-1BH10) WT or W153L viruses were generated as reported previously (17).

Assays of virion-associated RT activity.

Virion-associated RT activity was measured by in vitro RT assay as described previously (21), with 50-μl RT reaction mixtures containing 10 μl of culture supernatants (10 ng HIV-1 p24), 0.5 U/ml of poly(rA)/poly(dT)12–18 template/primer (T/P; template annealed to primer) (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 75 mM KCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Triton X-100, 2% ethylene glycol, 0.3 mM reduced glutathione, and 2.5 μCi [3H]dTTP (70 to 80 Ci/mmol, 2.5 mCi/ml). Following a 240-min incubation at 37°C, the reaction mixture was quenched by adding 0.2 ml of 10% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) containing 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate and incubated for at least 30 min on ice. The precipitated products were filtered onto Millipore 96-well multiscreen HTS FC filter plates (MSFCN6B) and sequentially washed with 200 μl of 10% TCA and 150 μl of 95% ethanol. The radioactivity of incorporated products was analyzed by liquid scintillation spectrometry using a Perkin-Elmer 1450 MicroBeta TriLux microplate scintillation and luminescence counter.

Measurements of HIV-1 replication capacity in TZM-bl cells.

The relative replicative capacities of the recombinant WT HIV-1NL4-3 clones containing the substitutions W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C were evaluated in a noncompetitive infectivity assay using TZM-bl cells as previously described (22, 23). Twenty thousand cells per well were added in triplicate into a 96-well culture plate in 100 μl of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON). Viral stocks for both wild-type and mutant viruses were normalized by p24, and recombinant viruses were serially diluted from viral stock suspensions. After 4 h, 50 μl of DMEM was removed from the wells and replaced by 50 μl of virus dilution; a control well did not contain virus. Viruses and cells were cocultured for 48 h, after which 100 μl of Promega luciferase assay Bright-Glo reagent (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON) was added and luciferase activity was measured in a 1450 MicroBeta TriLux microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) as described above. The viral replication level of each viral variant was expressed as the percentage of relative light units (RLU) with reference to the results for WT virus.

Analysis of phenotypic drug susceptibility in TZM-bl cells.

Phenotypic susceptibility analyses of RT inhibitors were performed with recombinant HIV-1NL4-3 clones in a TZM-bl cell-based in vitro assay as described previously (22, 24, 25). Briefly, RT inhibitors at variable concentrations were added to TZM-bl cells (104 cells/well) grown in 96-well plates in 100 μl of supplemented medium. Immediately after drug addition, cells were infected with WT or mutant viruses. At 48 h postinfection, cells were rinsed with 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and lysed with 50 μl/well Promega luciferase assay cell lysis reagent (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON). Cell lysates were then transferred to a white, opaque 96-well plate (Corning, Tewksbury, MA). Promega luciferase assay reagent (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON) was added to each well, and RLUs per well were measured by using a PerkinElmer 1450 MicroBeta TriLux microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) was calculated using the GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Recombinant reverse transcriptase expression and purification.

Recombinant RTs in heterodimeric form were expressed from plasmid pbRT6H-PROT (19) and purified as described previously (26, 27). In brief, RT expression in Escherichia coli M15 (pREP4) (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON) was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at room temperature. Pelleted bacteria were lysed under native conditions with BugBuster protein extraction reagent containing Benzonase (Novagen, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After clarification by high-speed centrifugation, the clear supernatant was subjected to the batch method of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) metal affinity chromatography (QIAexpressionist; Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada). All buffers contained complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Hexahistidine-tagged RT was eluted using an imidazole gradient. RT-containing fractions were pooled, passed through DEAE-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, ON, Canada), and further purified using SP Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Mississauga, ON). Fractions containing purified RT were pooled, dialyzed against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 50 mM NaCl, and 50% glycerol), and concentrated to 4 to 8 mg/ml with Centricon Plus-20 MWCO30 (molecular-weight cutoff, 30,000) centrifugal filters (Millipore, Etobicoke, ON, Canada). Aliquots of proteins were stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was measured by using a Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Saint-Laurent, QC, Canada), and the purity of the recombinant RT preparations was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity of each recombinant RT preparation was evaluated as described previously (28), using various concentrations of RT and a synthetic homopolymeric poly(rA)/poly(dT)12–18 T/P (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX). As a control, recombinant WT or W153L RT derived from HIV-1BH10 was generated as reported previously (17).

RT-catalyzed RNase H activity.

RNase H activity was assayed using a 41-mer 5′-end 32P-labeled heteropolymeric RNA template termed kim40R that was annealed to a complementary 32-nucleotide DNA oligomer termed kim32D at a 1:4 molar ratio as described previously (29, 30). The reactions were conducted at 37°C in mixtures containing an RNA-DNA duplex substrate (20 nM) with equal amounts of RT enzymes in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 60 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Aliquots were removed at different time points after the initiation of reactions and quenched by using an equal volume of formamide sample loading buffer (96% formamide, 0.1% each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol FF, and 20 mM EDTA). The samples were heated to 90°C for 3 min, cooled on ice, and electrophoresed through 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gels. The gels were analyzed by phosphorimaging.

Processivity assays.

The processivity of recombinant RT proteins was analyzed as described previously using heteropolymeric RNA template in the presence of a heparin enzyme trap to ensure a single processive cycle, i.e., a single round of binding and of primer extension and dissociation (29). The T/P was prepared by annealing the 497-nt HIV PBS RNA with the 5′-end 32P-labeled 25-nt DNA primer D25 at a molar ratio of 1:1, denaturing at 85°C for 5 min, and then slowly cooling to 55°C for 8 min and 37°C for 5 min to allow for specific annealing of the primer to the template. RT enzymes with equal amounts of activity and 40 nM T/P were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl, and 6 mM MgCl2. The reactions were initiated by the addition of dNTPs at 5 μM and heparin trap (final concentration, 3.2 mg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then, 2 volumes of stop solution (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% each xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue) were added to stop the reaction. The reaction products were denatured by heating at 95°C and analyzed by 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. The effectiveness of the heparin trap was verified in control reactions in which the trap was preincubated with substrate before the addition of RT enzymes and dNTPs.

RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity.

The same 497-nt RNA and 5′-end 32P-labeled D25 primers described previously (29) were used to assess the polymerization efficiencies of recombinant RT enzymes in time course experiments. The final reaction mixtures contained 20 nM T/P, 400 nM RT enzyme, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), and 50 mM NaCl. The reactions were initiated by adding 6 mM MgCl2 and dNTPs at 200 μM, and the reaction mixtures were sampled at 40 s and 60 s and mixed with 2 volumes of stop solution (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% each xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue). The reaction products were separated by 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed as described previously (29).

Incorporation efficiency of TFV-DP in gel-based primer extension assays.

The incorporation of tenofovir-diphosphate (TFV-DP) was monitored using DNA primer D25 and DNA template D42 (see Fig. 6 for sequences). The 5′-end 32P-labeled primer D25 was annealed to D42 at a molar ratio of 1:3. To monitor the inhibitory efficiency of TFV-DP, we performed a primer extension assay; the final reaction mixtures contained 20 nM T/P, RT enzymes at similar activity levels, 1 μM dNTPs, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl, and various concentrations of TFV-DP. The reactions were initiated by adding 6 mM MgCl2, and the mixtures incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The reactions were stopped by mixing in 2 volumes of stop solution (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% each xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue). The reaction products were separated by 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and analyzed as described above.

FIG 6.

Efficiency of TFV-DP inhibition of recombinant WT and mutant RT enzymes. (A) Graphic representation of the DNA template/DNA primer (D42/D25) substrate duplex used to monitor the efficiencies of TFV-DP inhibition of WT and mutant RTs. Positions of incorporation sites of TFV-DP are shown at the bottom. The 25-mer DNA primer was labeled at its 5′ terminus by 32P and annealed to a 42-mer DNA oligonucleotide (D42). (B) Inhibitory efficiency of TFV-DP was analyzed by monitoring full-length DNA (FL DNA) products in fixed-time primer extension experiments with RT enzymes at various concentrations of TFV-DP. Lanes 0 to 8 represent concentrations of TFV-DP at 0, 0.8, 1.6, 3.1, 6.3, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μM, respectively. Lanes P show the position of labeled D25 primer in a control reaction without RT enzymes. The positions of incorporation sites of TFV-DP and full-length DNA products are indicated on the left. All reactions were resolved by denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Experiments were repeated at least twice, with similar results being obtained each time. The gel is from a representative experiment.

Excision and rescue of chain-terminated DNA synthesis in the presence of ATP.

The assay was performed as described previously (31). Briefly, the 5′-end 32P-labeled DNA primer 17D was annealed to DNA template 57D and subsequently extended with TFV-DP using WT RT. Complete primer termination with TFV monophosphate (TFV-MP) was verified by primer extension assay using WT RT and denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Excision and the ensuing rescue of chain-terminated DNA synthesis were monitored in time course experiments (0 to 120 min) in the presence of 3.5 mM ATP (pretreated with inorganic pyrophosphatase) and a dNTP cocktail consisting of 100 μM dATP, 100 μM dTTP, 10 μM dCTP, and 100 μM ddGTP. All RT enzymes were normalized with equal amounts of activity as described previously (32). Samples were resolved by 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by phosphorimaging.

RESULTS

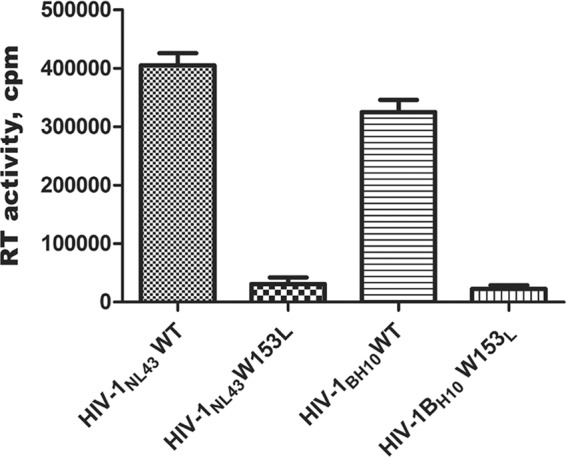

The W153L substitution in HIV-1 RT impairs virion-associated RT activity.

To validate the effect of the W153L substitution on RT activity in two HIV-1 variants, HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1BH10, equivalent amounts (10 ng p24) of virion-containing cell-free supernatants of transfected 293T cells were assessed. The W153L viral mutants from both HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1BH10 showed significantly decreased RT activity, i.e., 7.7% and 6.9% of the corresponding WT activities, respectively (Fig. 1). The W153L mutants of HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1BH10 exhibited similar levels of RT activity. The levels of RT activity associated with the two WT viruses were also similar. Unless specified, viruses derived from HIV-1NL4-3 were used in this study.

FIG 1.

Virus particle-associated RT activities. Clarified virus-containing culture supernatants (10 ng viral p24) were assayed for RNA-dependent DNA polymerase activity by the incorporation of [3H]dTTP into poly(rA)/poly(dT)12–18. Reaction mixtures were prepared as described in Materials and Methods, incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and quenched with 10% trichloroacetic acid–sodium pyrophosphate. Values represent incorporated radioactivity measured as counts per minute (cpm). Each bar represents the means of three separate measurements. Error bars represent standard deviations.

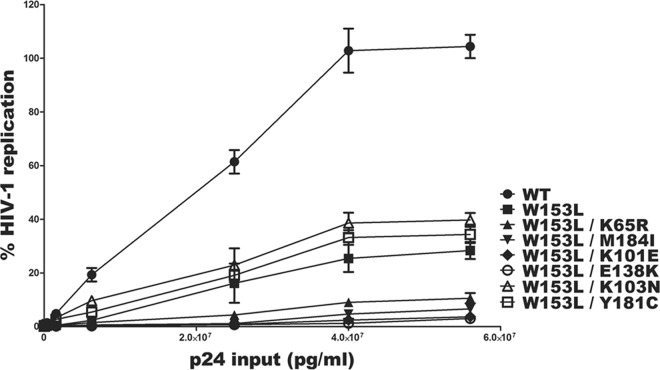

The W153L substitution, alone or in tandem with the common resistance substitutions K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, diminishes viral replication capacity.

The W153L substitution alone has been shown to impair viral replication capacity in Jurkat cells (21). We wished to investigate the impact of interactions between W153L and each of the substitutions K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C on viral replication. For this purpose, we used a well-established noncompetitive high-throughput infectivity assay with TZM-bl cells that were infected with recombinant HIV-1 viruses that were normalized in terms of inoculum on the basis of p24 antigen (22, 23). The infectiousness of the WT and mutant viruses was determined by measuring luciferase activity at 48 h postinfection. The results show that the replication of all the mutant viruses containing W153L was diminished compared to that of the WT (Fig. 2). At a p24 input of 2.5 × 107 pg/ml, the replication capacity of virus containing W153L alone was decreased by ∼7-fold compared to that of the WT, consistent with previous observations (17). Our data also show even further impairments of mutant viruses containingW153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, and W153L/E138K, by ∼14-fold compared to the replication capacity of the WT. In contrast, the W153L/K103N and W153L/Y181C mutant viruses were only diminished in replication capacity by ∼3-fold.

FIG 2.

The HIV-1 RT substitution W153L impairs viral replication capacity alone or in the background of each of the RT substitutions K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C. Viral stocks of a wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 clone and W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C viruses were normalized for p24 and used to infect TZM-bl cells. Luciferase activity was measured at 48 h postinfection as an indication of viral replication. The infectivities of mutant viruses relative to that of the WT are shown on the y axis, while the x axis denotes the input of p24. The data are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

W153L enhances susceptibility to TFV.

It was previously shown that HIV-1 containing W153L displays high-level resistance to the novel NcRTI compound A (160-fold that of the WT) without an effect on susceptibility to NVP (17). In contrast, W153L conferred hypersusceptibility (5- to 10-fold) to the NtRTIs ABC, TFV, 3TC, and FTC. Here, we determined the effect of W153L, alone or in combination with each of the RAMs K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, on susceptibility to each of the NRTIs TFV and 3TC, the NNRTIs ETR, RPV, EFV, and NVP, and the NcRTI compound A in TZM-bl cells. Table 1 shows that all of the W153L-containing mutant viruses, including W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C viruses, displayed high-level (>133-fold) resistance to the novel NcRTI compound A, confirming that W153L plays a crucial rule in conferring resistance to this compound. Moreover, the presence of W153L together with other common RT resistance substitutions did not reverse resistance to compound A. K65R on its own conferred hypersusceptibility to compound A (0.3-fold), in agreement with a previous report (17). In contrast, virus with M184I alone displayed a slight resistance to compound A (2.5-fold). This indicates that M184I, like M184V, as demonstrated in a previous report (17), confers modest resistance to compound A.

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibilities of HIV-1NL4–3 wild-type and recombinant site-directed mutant viruses containing W153L alone or together with other substitutions in reverse transcriptase as assessed in TZM-bl culturesa

| Enzyme variant | Mean viral EC50 (fold change in resistance) ± SD |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFV (μM) | 3TC (μM) | NVP (nM) | EFV (nM) | ETR (nM) | RPV (nM) | Compound A (nM) | |

| WT | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0 | 51.3 ± 12 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 2.5 |

| W153L | 1.4 ± 0.3 (0.3) | 0.1 ± 0.1 (0.3) | 41 ± 1.4 (0.8) | 1.1 ± 0.1 (0.5) | 0.9 ± 0.3 (0.9) | 0.2 ± 0.3 (0.7) | >1,000 (>133) |

| W153L/K65R | 1.3 ± 0.5 (0.3) | 2.1 ± 0.3 (7) | 36.5 ± 8 (0.7) | 1.1 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0.8) | 0.2 ± 0.2 (0.7) | >1,000 (>133) |

| K65R | 12.7 ± 3 (2.7) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2.3 ± 0.3 (0.3) |

| W153L/M184I | 1.9 ± 0.6 (0.4) | >100 (>333) | 31.8 ± 7 (0.6) | ND | 1 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.4 ± 0.1 (1.4) | >1,000 (>133) |

| M184I | ND | >100 (>333) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18.8 ± 2.4 (2.5) |

| W153L/K101E | 2.5 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 0.4 ± 0.1 (1.2) | >3,000 (>60) | 2 ± 1 (1) | 2.5 ± 0.3 (2.5) | 0.6 ± 0.3 (2) | >1,000 (>133) |

| W153L/K103N | 1.2 ± 0.1 (0.3) | 0.3 ± 0 (1) | >3,000 (>60) | 2.7 ± 2 (1.4) | 0.7 ± 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 ± 0.1 (0.7) | >1,000 (>133) |

| W153L/E138K | 1.8 ± 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 ± 0.1 (1.3) | 51 ± 9 (1) | 1.9 ± 1.4 (1) | 1.8 ± 0.4 (1.8) | 0.4 ± 0.3 (1.3) | >1,000 (>133) |

| W153L/Y181C | 2.5 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 0.3 ± 0.1 (0.9) | >3,000 (>60) | 2.5 ± 1.5 (1.3) | 1.9 ± 0.5 (1.9) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (1.7) | >1,000 (>133) |

Data are the results of 3 independent experiments. EC50, 50% drug effective concentration; ND, not determined.

In regard to NNRTIs, the W153L-containing viruses displayed little or no resistance to ETR, RPV, NVP, and EFV. Moreover, W153L did not enhance the resistance to these compounds conferred by common NNRTI-related substitutions. The W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, and W153L/Y181C double mutants conferred high-level resistance (>60-fold that of the WT) to NVP, while all the other mutant viruses were susceptible to NVP. The roles of each of the K101E, K103N E138K, and Y181C substitutions in regard to NNRTI resistance have been well characterized previously (33–36).

Virus with W153L alone displayed hypersusceptibility to 3TC, as demonstrated by its fold change in EC50 (0.3-fold) compared to the WT EC50, consistent with previous observations (17). However, the W153L/M184I combination conferred high-level resistance to 3TC, as did M184I alone, indicating that W153L could not reverse the 3TC resistance phenotype of M184I. None of the other W153L double mutants showed resistance to 3TC.

For TFV, virus with W153L alone displayed hypersusceptibility, as demonstrated by a 0.3-fold change in EC50 compared to that of the WT. Interestingly, the W153L/K65R double mutant reversed the resistance associated with K65R (2.7-fold change in EC50) to a phenotype of hypersusceptibility (0.3-fold change). Hypersusceptibility to TFV was also observed with all the double mutants, with fold changes in EC50 of 0.3 to 0.5. These data show that W153L can enhance TFV susceptibility and can reverse the TFV resistance that is associated with K65R. In agreement with previous reports (17), K65R alone displayed hypersusceptibility to compound A, as demonstrated by a 0.2-fold change in EC50 compared to that of the WT.

The W153L substitution, alone or in tandem with common resistance substitutions at positions K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, impairs enzyme processivity.

Diminished HIV-1 RT processivity is a determinant of impaired viral replication capacity (37–40). For example, the M184I/V substitution is associated with a deficit in enzyme processivity, which, in turn, can be correlated with lower replication fitness, especially in cell types that have low dNTP pools (37, 41). To investigate whether W153L, alone or in the presence of other common resistance substitutions, i.e., K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, might affect enzyme processivity, we performed gel-based single-cycle processivity assays using recombinant RT enzymes of the WT or containing each of the substitutions mentioned above. The initial experiments were performed with 0.5 μM dNTPs, and we found that the mutant RT enzymes were barely able to extend the primer (not shown). In order to enhance extension and better validate relative processivity among RT variants, we next used 5 μM dNTP in the processivity assays. The results in Fig. 3 show that only WT RT was able to synthesize substantial amounts of full-length DNA product, i.e., 471 nt in length in this circumstance. In contrast, all of the mutant W153L-containing RT enzymes were diminished in processivity, as demonstrated by shorter DNA products compared with those of the WT RT control (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained with the BH10 WT and W153L RTs as with the NL4-3 WT and W153L RTs (not shown). These findings show that the W153L substitution in RT, alone or in combination with each of the K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C substitutions, impairs enzyme processivity. Therefore, the lower replication capacity of W153L-containing viruses is correlated with a defect in RT enzyme processivity.

FIG 3.

Comparative analysis of enzyme processivity of WT RT and RT enzymes containing the W153L substitution, alone or in combination with other mutations. The processivity of purified recombinant RT enzymes was analyzed using 5′-end-labeled DNA primer (D25) annealed to a 471-nt HIV-1 PBS RNA template as the substrate; the resulting full-length DNA is 471 nt in length. Processivity was determined by the size distribution of DNA products in fixed-time experiments at 5 μM dNTP in the presence of heparin trap. The sizes of some fragments of the 32P-labeled 25-bp DNA ladder in nucleotide (nt) bases are indicated on the left side of the panel. All reaction products were resolved by denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphor imaging. The position of the 32P-labeled D25 primer is indicated on the right. The image is representative of three independent experiments, in all of which similar results were obtained.

The W153L substitution, alone or in tandem with common resistance substitutions, diminishes the efficiency of DNA synthesis.

In addition to enzyme processivity, RT polymerization efficiency is an important determinant of viral replication capacity that can also be assessed by primer extension efficiency in gel-based assays. For example, E138K RT is known to have processivity similar to that of WT RT but causes a decrease in the efficiency of RT polymerization at high dNTP concentrations (29). In contrast, M184I does not result in a defect in the efficiency of polymerization at high dNTP concentrations (29, 42), but the simultaneous presence of M184I and E138K can restore the efficiency of processive DNA synthesis and viral replication capacity (29). Another example is the N348I substitution in the connection subdomain of HIV-1 RT, which significantly decreases catalytic efficiency (43) and diminishes polymerization efficiency without impairing enzyme processivity, as demonstrated in gel-based assays (30). To determine whether W153L might affect the efficiency of DNA polymerization, we ran gel-based RNA-dependent DNA polymerase assays at high dNTP concentrations (200 μM) in time course experiments using the WT, W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C recombinant RT enzymes. RT molecules were used at ∼20-fold excess over the substrate, so that any RTs that dissociated from the primer terminus during synthesis would be rapidly replaced and the rate-limiting step would be the addition of nucleotides (29, 42). The efficiency of polymerization among RT variants was compared by studying the longest extension products at 60 s (Fig. 4, arrows). The results in Fig. 4 reveal that W153L RT enzyme showed a decreased efficiency of primer extension compared to that of WT RT, as seen by the longest extension products after 60 s of polymerization. The W153L/M184I, W153L/K103N, and W153L/Y181C double-variant enzymes showed impairments in efficiency of polymerization similar to that of W153L RT alone. However, the W153L/K65R, W153L/K101E and W153L/E138K double mutants all showed further impairments in efficiency of primer extension. The results obtained with the BH10 WT and W153L RTs were similar to those obtained with the NL4-3 WT and W153L RTs (data not shown). These data confirm that W153L-containing RTs are impaired in efficiency of processive DNA synthesis and that this contributes to the lower replication capacity of W153L-containing viruses.

FIG 4.

Time course experiments showing the effects of the W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C substitutions in HIV-1 RT on the efficiency of processive DNA polymerization. The 32P-labeled D25 primer was annealed to the 497-nt RNA template, and extension assays were performed with an excess of recombinant RT enzymes and dNTP concentrations of 200 μM. Reactions were stopped at 40 s and 60 s, respectively. All reaction products were resolved by denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimaging. Sizes of some fragments of the 32P-labeled 25-bp DNA ladder in nucleotide (nt) bases are indicated on the left side of the panel. The position of 32P-labeled D25 primer is indicated on the right. The longest extension products generated at 60 s are identified by arrows and indicate differences in the efficiency of polymerization. The gel is from a representative experiment.

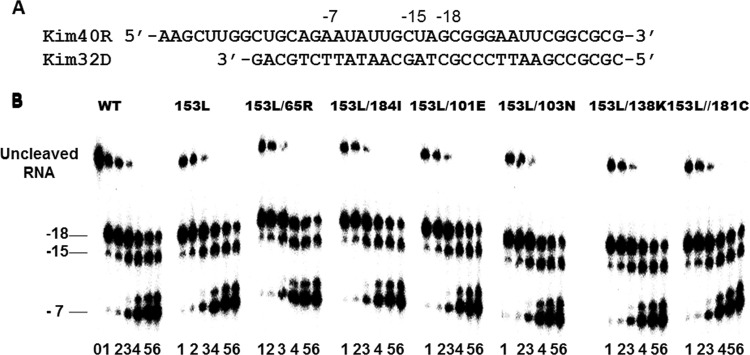

W153L does not diminish RNase H activity, either alone or in a background of RT containing K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, or Y181C.

Substitutions at certain residues in HIV-1 RT can impair RNase H activity and contribute to reductions in HIV-1 replication fitness (44, 45). In addition, some NNRTI resistance substitutions are associated with impaired RNase H activity (44, 46–50), and reduced RNase H activity may also be associated with enhanced resistance to both NRTIs and NNRTIs (51, 52). To investigate the effect of W153L, alone or in a background of K65R, M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, or Y181C, on RNase H activity, we monitored multicycle RNase H-mediated RNA cleavage in time course experiments using WT RT and the W153L, W153L/K65R, W153L/M184I, W153L/K101E, W153L/K103N, W153L/E138K, and W153L/Y181C variants. The results showed that all the mutant enzymes yielded the same cleavage profiles and at the same efficiencies as did WT enzyme, as demonstrated by the relative band densities of the uncleaved RNA substrates and the cleaved products (Fig. 5). These data demonstrate that the W153L substitution, either alone or in combination with other resistance substitutions, did not diminish RNase H activity. Thus, RNase H probably does not contribute to the diminished viral replication capacity associated with viruses containing these various substitutions.

FIG 5.

RNase H activities of WT and mutant recombinant RT enzymes. (A) Graphic representation of the RNA/DNA (kim40R/kim32D) substrate duplex used to monitor the cleavage efficiencies of mutant and WT RTs. Positions of cleavage sites relative to the 3′ end of the primer are shown at the top. The 40-mer RNA kim40R was labeled at its 5′ terminus by 32P and annealed to a 32-mer DNA oligonucleotide (kim32D). (B) RNase H activity was analyzed by monitoring substrate cleavage at 0.2, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, and 10 min (lanes 1 to 6, respectively) in time course experiments. Lane 0 (time point 0) shows the uncleaved substrate in a control reaction without RT enzyme. The uncleaved substrate and cleaved products relative to the 3′ terminus of the DNA primer are indicated on the left. All reactions were resolved by denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results being obtained each time. The gel is from a representative experiment.

W153L enhances the incorporation of TFV-DP in gel-based primer extension assays.

The two major mechanisms that account for resistance to NRTIs are discrimination and excision (for reviews, see references 11 and 12). In discrimination, the mutant RT enzyme has decreased incorporation efficiency of NRTIs relative to that of the natural dNTP substrate. The consequence is diminished incorporation of drugs into the DNA chain. In order to determine the biochemical mechanism of the phenomenon of W153L variant HIV-1 hypersusceptibility to TFV in cell-based assays, we performed primer extension assays at a fixed concentration of dNTPs (1 μM) to compare the efficiency of incorporation of TFV-DP in DNA-dependent DNA polymerization by WT, W153L, and K65R RT enzymes (Fig. 6). The use of the W153L RT mutant resulted in a 3-fold increase in susceptibility to TFV-DP, as demonstrated by a fold change in 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.3 compared to IC50 of the WT (Table 2). In contrast, the K65R mutant RT yielded a decrease in susceptibility to TFV-DP, as demonstrated by a 3.3-fold change in IC50 compared to that of the WT. These data are consistent with the results of studies performed using cell-based assays. The 3-fold decrease in IC50 for TFV-DP as a result of the W153L mutation within RT suggests that this substitution can enhance the incorporation efficiency of TFV-DP.

TABLE 2.

TFV-DP susceptibilities of HIV-1 viruses with recombinant RT enzymes as assessed in gel-based primer extension assays

| Enzyme variant | Mean viral IC50 ± SDa | Fold change in resistance |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 1 |

| W153L | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.3 |

| K65R | 11.4 ± 1.7 | 3.3 |

Data are the results of 3 independent experiments. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration.

Efficiency of ATP-dependent excision of TFV-MP and rescue of DNA synthesis.

The excision of incorporated NRTIs is a second mechanism whereby resistance to NRTIs by mutant RTs can occur. Using the WT, W153L, and K65R recombinant RT enzymes, we determined the efficiencies of excision of TFV-MP in gel-based ATP-dependent excision/rescue experiments. The results in Fig. 7A and B show that the W153L RT only displayed a modestly diminished efficiency of excision of incorporated TFV-MP, while the K65R RT severely compromised this activity. These data indicate that the slightly decreased excision efficiency of the W153L RT cannot account for the hypersusceptibility of TFV that is associated with the W153L substitution.

FIG 7.

Efficiencies of ATP-dependent unblocking of TFV-MP-terminated primer and rescue of DNA synthesis by WT and mutant RT enzymes. (A) The primer 17D was initially 5′ end labeled with [γ32P]ATP, annealed to DNA template 57D, and chain terminated with TFV-DP. Combined excision/rescue reactions were compared in time course experiments. Lanes 1 to 8 represent time points at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min, respectively. Experiments were repeated at least twice, with similar results being obtained each time. The gel is from a representative experiment. (B) Graphic representation of efficiencies of rescue of DNA synthesis from the representative gel-based experiment.

DISCUSSION

Due to the pivotal role of HIV-1 RT in viral replication and the fact that drug resistance occurs against all RTIs, efforts are required toward the development of new antiretroviral compounds with distinct mechanisms and resistance profiles. The recent identification of a novel BFPY NcRTI compound termed compound A is exciting. In spite of its improved antiviral potency, however, compound A selects for a substitution at position W153L in RT and does not possess an advantageous pharmacokinetic profile. Nonetheless, compound A possesses a superior profile compared with that of the NcRTI known as INDOPY-1, which displays overlapping resistance with certain NRTIs, such as 3TC and FTC. Furthermore, most substitutions associated with decreased susceptibility to INDOPY-1 are clustered around the dNTP binding site (13–15).

The W153 residue in HIV-1 RT is highly conserved but is not located at the dNTP binding site. Until recently, this substitution had not been associated with resistance to NNRTIs or NRTIs (17). The W153L substitution appears not only to confer drug resistance but also to play a critical role in RT structure and function. Ours is the first study to characterize W153L by both cell-based and biochemical methods. We show that W153L, alone or in a background of clinically relevant substitutions for NRTIs and NNRTIs, severely diminished viral replicative fitness by impairing enzyme processivity and polymerization efficiency. We have also provided phenotyping data that demonstrate that W153L can reverse the resistance to TFV conferred by K65R and that W153L together with K65R can yield hypersusceptibility to TFV.

K65R confers reduced susceptibility not only to TFV but also to most NRTIs except zidovudine (53). An increasing number of reports now show that the occurrence of K65R is increasing worldwide, especially in subtype C-infected patients who have failed antiretroviral therapy (54–56). It was previously shown that K65R confers hypersusceptibility to compound A, while W153L confers hypersusceptibility to TFV (17). Our phenotyping data in TZM-bl cells now confirm this mutual hypersusceptibility and, more importantly, we also demonstrate that W153L together with K65R can hypersensitize viruses to TFV. This unique phenotype may make it advantageous to coadminister an NcRTI with a resistance profile similar to that of compound A with TFV to suppress viral replication, as well as to suppress viruses resistant to either of these drugs. Previously, K65R variants were shown to be hypersusceptible to earlier NcRTI compounds, such as INDOPY-1, and to another investigational RT inhibitor, i.e., 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) (57). Resistance to INDOPY-1 was conferred by M184V (5-fold) (58). It was also previously shown that combining TFV with INDOPY-1 in cell culture can prevent the selection of resistance (59). However, the simultaneous presence of K65R with M184V did not result in hypersusceptibility to INDOPY-1, unlike the combination of K65R with W153L in regard to compound A. We are currently studying whether combining TFV with compound A may affect the selection of resistance to both of these compounds. The mechanism of K65R resistance to TFV has been demonstrated to be a combination of decreased drug incorporation and decreased excision that both occur in a balanced fashion (60, 61). Here, we have shown that the mechanism of TFV hypersusceptibility that is conferred by the W153L substitution is mainly due to increased efficiency of incorporation of TFV-DP by RT.

The emergence of HIV-1 drug resistance is often associated with reductions in viral fitness, but the subsequent selection of additional compensatory substitutions can often restore fitness while increasing levels of resistance (62). Here, we have demonstrated that W153L-harboring viruses display diminished replicative fitness compared to that of WT virus. No compensatory effects were observed between W153L and other clinically relevant substitutions that confer resistance against NRTIs or NNRTIs.

The mechanisms underlying the diminished viral replicative fitness of W153L-containing viruses have been addressed here using purified recombinant RT enzymes. We have shown by gel-based assays that W153L is associated with decreased RT processivity and polymerization efficiency. The fact that the W153L substitution, alone or in combination with other common resistance substitutions, has a negative impact on RT polymerase function may be encouraging in regard to future development of antiretroviral drugs that select for this substitution. Further structural and biochemical studies of the role of the W153 residue are in progress in our laboratory.

Previous findings from our laboratory and by others have shown that RT polymerase functions can be affected by interactions between HIV-1 drug resistance substitutions. For example, a mutual compensatory effect exists between E138K and M184I in regard to enzyme processivity and polymerization efficiency (29, 63, 64). In contrast, an antagonistic interaction exists between Y181C and E138K that results in more severe impairment in enzyme processivity and polymerization efficiency (34), which explains why Y181C may prevent the emergence of E138K in cell culture under conditions of selection with ETR. More recently, the N348I substitution in the connection domain of RT was also shown to restrict the emergence of E138K in cell culture as a result of a negative impact on RT polymerization efficiency (30). Future studies should document how W153L affects the transit kinetics of reverse transcription and further detail the mechanisms of resistance and hypersusceptibility associated with this substitution.

In conclusion, we have provided virological data demonstrating that W153L, either alone or in a background of K65R or other clinically relevant RAMs, such as M184I, K101E, K103N, E138K, and Y181C, can enhance susceptibility to TFV. Moreover, K65R conferred hypersusceptibility to the NcRTI termed compound A, and W153L, alone or in tandem with other resistance substitutions, impaired enzyme processivity and efficiency of polymerization, albeit without diminishing RNase H activity. We have also shown that the mechanism of TFV hypersusceptibility conferred by the W153L substitution in RT is due to increased efficiency of TFV-DP incorporation, which occurs without compromising the efficiency of excision.

These data demonstrate that combining an NcRTI, such as compound A, with TFV or a new prodrug of TFV termed tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) could suppress K65R resistance and that the emergence of W153L may also be restricted in this circumstance. In the likelihood that the pharmacology of compound A will make it unsuitable for clinical development, the synthesis and evaluation of derivatives of compound A that possess excellent tolerability and pharmacokinetics (65) while sharing its resistance profile should be pursued.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Daniel Rajotte and Richard Bethell were employees of BoehringerIngelheim (Canada) Ltd., Laval, Quebec, Canada when this study was initiated. We have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts EJ, Hazuda DJ. 2012. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a007161. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arribas JR, Eron J. 2013. Advances in antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 8:341–349. 10.1097/COH.0b013e328361fabd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Aquila RT, Hughes MD, Johnson VA, Fischl MA, Sommadossi JP, Liou SH, Timpone J, Myers M, Basgoz N, Niu M, Hirsch MS. 1996. Nevirapine, zidovudine, and didanosine compared with zidovudine and didanosine in patients with HIV-1 infection. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 241 Investigators Ann. Intern. Med. 124:1019–1030. 10.7326/0003-4819-124-12-199606150-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, Blanc C, Mathez D, Tubiana R, Katlama C, Debre P, Leibowitch J. 1997. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science 277:112–116. 10.1126/science.277.5322.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menendez-Arias L. 2010. Molecular basis of human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance: an update. Antiviral Res. 85:210–231. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarafianos SG, Marchand B, Das K, Himmel DM, Parniak MA, Hughes SH, Arnold E. 2009. Structure and function of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: molecular mechanisms of polymerization and inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 385:693–713. 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wainberg MA. 2003. HIV resistance to nevirapine and other non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 34(Suppl 1):S2–S7. 10.1097/00126334-200309011-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wainberg MA, Zaharatos GJ, Brenner BG. 2011. Development of antiretroviral drug resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:637–646. 10.1056/NEJMra1004180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh K, Marchand B, Kirby KA, Michailidis E, Sarafianos SG. 2010. Structural aspects of drug resistance and inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Viruses 2:606–638. 10.3390/v2020606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren J, Stammers DK. 2008. Structural basis for drug resistance mechanisms for non-nucleoside inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase. Virus Res. 134:157–170. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menendez-Arias L. 2008. Mechanisms of resistance to nucleoside analogue inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Virus Res. 134:124–146. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez-Arias L. 2013. Molecular basis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance: overview and recent developments. Antiviral Res. 98:93–120. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jochmans D, Deval J, Kesteleyn B, Van Marck H, Bettens E, De Baere I, Dehertogh P, Ivens T, Van Ginderen M, Van Schoubroeck B, Ehteshami M, Wigerinck P, Gotte M, Hertogs K. 2006. Indolopyridones inhibit human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase with a novel mechanism of action. J. Virol. 80:12283–12292. 10.1128/JVI.00889-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Walker M, Xu W, Shim JH, Girardet JL, Hamatake RK, Hong Z. 2006. Novel nonnucleoside inhibitors that select nucleoside inhibitor resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2772–2781. 10.1128/AAC.00127-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehteshami M, Scarth BJ, Tchesnokov EP, Dash C, Le Grice SF, Hallenberger S, Jochmans D, Gotte M. 2008. Mutations M184V and Y115F in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase discriminate against “nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitors”. J. Biol. Chem. 283:29904–29911. 10.1074/jbc.M804882200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jegede O, Khodyakova A, Chernov M, Weber J, Menendez-Arias L, Gudkov A, Quinones-Mateu ME. 2011. Identification of low-molecular weight inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase using a cell-based high-throughput screening system. Antiviral Res. 91:94–98. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajotte D, Tremblay S, Pelletier A, Salois P, Bourgon L, Coulombe R, Mason S, Lamorte L, Sturino CF, Bethell R. 2013. Identification and characterization of a novel HIV-1 nucleotide-competing reverse transcriptase inhibitor series. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:2712–2718. 10.1128/AAC.00113-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arts EJ, Li X, Gu Z, Kleiman L, Parniak MA, Wainberg MA. 1994. Comparison of deoxyoligonucleotide and tRNA(Lys-3) as primers in an endogenous human immunodeficiency virus-1 in vitro reverse transcription/template-switching reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 269:14672–14680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu HT, Quan Y, Asahchop E, Oliveira M, Moisi D, Wainberg MA. 2010. Comparative biochemical analysis of recombinant reverse transcriptase enzymes of HIV-1 subtype B and subtype C. Retrovirology 7:80. 10.1186/1742-4690-7-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imamichi T, Berg SC, Imamichi H, Lopez JC, Metcalf JA, Falloon J, Lane HC. 2000. Relative replication fitness of a high-level 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine-resistant variant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 possessing an amino acid deletion at codon 67 and a novel substitution (Thr–>Gly) at codon 69. J. Virol. 74:10958–10964. 10.1128/JVI.74.23.10958-10964.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff SP. 1990. Retroviral reverse transcriptase: synthesis, structure, and function. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:817–831 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asahchop EL, Oliveira M, Wainberg MA, Brenner BG, Moisi D, Toni T, Tremblay CL. 2011. Characterization of the E138K resistance mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase conferring susceptibility to etravirine in B and non-B HIV-1 subtypes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:600–607. 10.1128/AAC.01192-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu HT, Quan Y, Schader SM, Oliveira M, Bar-Magen T, Wainberg MA. 2010. The M230L nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase impairs enzymatic function and viral replicative capacity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2401–2408. 10.1128/AAC.01795-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schader SM, Oliveira M, Ibanescu RI, Moisi D, Colby-Germinario SP, Wainberg MA. 2012. In vitro resistance profile of the candidate HIV-1 microbicide drug dapivirine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:751–756. 10.1128/AAC.05821-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asahchop EL, Wainberg MA, Oliveira M, Xu H, Brenner BG, Moisi D, Ibanescu IR, Tremblay C. 2013. Distinct resistance patterns to etravirine and rilpivirine in viruses containing nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor mutations at baseline. AIDS 27:879–887. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835d9f6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Grice SF, Cameron CE, Benkovic SJ. 1995. Purification and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Methods Enzymol. 262:130–144. 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Grice SF, Gruninger-Leitch F. 1990. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. Eur. J. Biochem. 187:307–314. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quan Y, Brenner BG, Marlink RG, Essex M, Kurimura T, Wainberg MA. 2003. Drug resistance profiles of recombinant reverse transcriptases from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes A/E, B, and C. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 19:743–753. 10.1089/088922203769232548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu HT, Asahchop EL, Oliveira M, Quashie PK, Quan Y, Brenner BG, Wainberg MA. 2011. Compensation by the E138K mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase for deficits in viral replication capacity and enzyme processivity associated with the M184I/V mutations. J. Virol. 85:11300–11308. 10.1128/JVI.05584-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu HT, Colby-Germinario SP, Oliveira M, Han Y, Quan Y, Zanichelli V, Wainberg MA. 2014. The connection domain mutation N348I in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase enhances resistance to etravirine and rilpivirine but restricts the emergence of the E138K resistance mutation by diminishing viral replication capacity. J. Virol. 88:1536–1547. 10.1128/JVI.02904-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu HT, Martinez-Cajas JL, Ntemgwa ML, Coutsinos D, Frankel FA, Brenner BG, Wainberg MA. 2009. Effects of the K65R and K65R/M184V reverse transcriptase mutations in subtype C HIV on enzyme function and drug resistance. Retrovirology 6:14. 10.1186/1742-4690-6-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotte M, Arion D, Parniak MA, Wainberg MA. 2000. The M184V mutation in the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 impairs rescue of chain-terminated DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 74:3579–3585. 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3579-3585.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu H, Quan Y, Brenner BG, Bar-Magen T, Oliveira M, Schader SM, Wainberg MA. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 recombinant reverse transcriptase enzymes containing the G190A and Y181C resistance mutations remain sensitive to etravirine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4667–4672. 10.1128/AAC.00800-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu HT, Oliveira M, Asahchop EL, McCallum M, Quashie PK, Han Y, Quan Y, Wainberg MA. 2012. Molecular mechanism of antagonism between the Y181C and E138K mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 86:12983–12990. 10.1128/JVI.02005-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson VA, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, Paredes R, Pillay D, Shafer RW, Wensing AM, Richman DD. 2013. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: March 2013. Top. Antivir. Med. 21:6–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu HT, Colby-Germinario SP, Huang W, Oliveira M, Han Y, Quan Y, Petropoulos CJ, Wainberg MA. 2013. Role of the K101E substitution in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase in resistance to rilpivirine and other nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:5649–5657. 10.1128/AAC.01536-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Back NK, Nijhuis M, Keulen W, Boucher CA, Oude Essink BO, van Kuilenburg AB, van Gennip AH, Berkhout B. 1996. Reduced replication of 3TC-resistant HIV-1 variants in primary cells due to a processivity defect of the reverse transcriptase enzyme. EMBO J. 15:4040–4049 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caliendo AM, Savara A, An D, DeVore K, Kaplan JC, D'Aquila RT. 1996. Effects of zidovudine-selected human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase amino acid substitutions on processive DNA synthesis and viral replication. J. Virol. 70:2146–2153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naeger LK, Margot NA, Miller MD. 2001. Increased drug susceptibility of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutants containing M184V and zidovudine-associated mutations: analysis of enzyme processivity, chain-terminator removal and viral replication. Antivir. Ther. 6:115–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma PL, Crumpacker CS. 1999. Decreased processivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase (RT) containing didanosine-selected mutation Leu74Val: a comparative analysis of RT variants Leu74Val and lamivudine-selected Met184Val. J. Virol. 73:8448–8456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Back NK, Berkhout B. 1997. Limiting deoxynucleoside triphosphate concentrations emphasize the processivity defect of lamivudine-resistant variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2484–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao L, Hanson MN, Balakrishnan M, Boyer PL, Roques BP, Hughes SH, Kim B, Bambara RA. 2008. Apparent defects in processive DNA synthesis, strand transfer, and primer elongation of Met-184 mutants of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase derive solely from a dNTP utilization defect. J. Biol. Chem. 283:9196–9205. 10.1074/jbc.M710148200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuckmann MM, Marchand B, Hachiya A, Kodama EN, Kirby KA, Singh K, Sarafianos SG. 2010. The N348I mutation at the connection subdomain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase decreases binding to nevirapine. J. Biol. Chem. 285:38700–38709. 10.1074/jbc.M110.153783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerondelis P, Archer RH, Palaniappan C, Reichman RC, Fay PJ, Bambara RA, Demeter LM. 1999. The P236L delavirdine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutant is replication defective and demonstrates alterations in both RNA 5′-end- and DNA 3′-end-directed RNase H activities. J. Virol. 73:5803–5813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palaniappan C, Wisniewski M, Jacques PS, Le Grice SF, Fay PJ, Bambara RA. 1997. Mutations within the primer grip region of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase result in loss of RNase H function. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11157–11164. 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Archer RH, Dykes C, Gerondelis P, Lloyd A, Fay P, Reichman RC, Bambara RA, Demeter LM. 2000. Mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase resistant to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors demonstrate altered rates of RNase H cleavage that correlate with HIV-1 replication fitness in cell culture. J. Virol. 74:8390–8401. 10.1128/JVI.74.18.8390-8401.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Archer RH, Wisniewski M, Bambara RA, Demeter LM. 2001. The Y181C mutant of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase resistant to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors alters the size distribution of RNase H cleavages. Biochemistry 40:4087–4095. 10.1021/bi002328a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan N, Rank KB, Slade DE, Poppe SM, Evans DB, Kopta LA, Olmsted RA, Thomas RC, Tarpley WG, Sharma SK. 1996. A drug resistance mutation in the inhibitor binding pocket of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase impairs DNA synthesis and RNA degradation. Biochemistry 35:9737–9745. 10.1021/bi9600308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Figueiredo A, Zelina S, Sluis-Cremer N, Tachedjian G. 2008. Impact of residues in the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor binding pocket on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase heterodimer stability. Curr. HIV Res. 6:130–137. 10.2174/157016208783885065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Dykes C, Domaoal RA, Koval CE, Bambara RA, Demeter LM. 2006. The HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutants G190S and G190A, which confer resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, demonstrate reductions in RNase H activity and DNA synthesis from tRNA(Lys, 3) that correlate with reductions in replication efficiency. Virology 348:462–474. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikolenko GN, Delviks-Frankenberry KA, Pathak VK. 2010. A novel molecular mechanism of dual resistance to nucleoside and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J. Virol. 84:5238–5249. 10.1128/JVI.01545-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikolenko GN, Delviks-Frankenberry KA, Palmer S, Maldarelli F, Fivash MJ, Jr, Coffin JM, Pathak VK. 2007. Mutations in the connection domain of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase increase 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:317–322. 10.1073/pnas.0609642104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller MD. 2004. K65R, TAMs and tenofovir. AIDS Rev. 6:22–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doualla-Bell F, Avalos A, Brenner B, Gaolathe T, Mine M, Gaseitsiwe S, Oliveira M, Moisi D, Ndwapi N, Moffat H, Essex M, Wainberg MA. 2006. High prevalence of the K65R mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C isolates from infected patients in Botswana treated with didanosine-based regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4182–4185. 10.1128/AAC.00714-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyagoba F, Dunn DT, Pillay D, Kityo C, Robertson V, Tugume S, Hakim J, Munderi P, Chirara M, Ndembi N, Goodall RL, Yirrell DL, Burke A, Gilks CF, Kaleebu P. 2010. Evolution of drug resistance during 48 weeks of zidovudine/lamivudine/tenofovir in the absence of real-time viral load monitoring. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 55:277–283. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ea0df8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wallis CL, Erasmus L, Varughese S, Ndiweni D, Stevens WS. 2009. Emergence of drug resistance in HIV-1 subtype C infected children failing the South African national antiretroviral roll-out program. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28:1123–1125. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181af5a00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michailidis E, Ryan EM, Hachiya A, Kirby KA, Marchand B, Leslie MD, Huber AD, Ong YT, Jackson JC, Singh K, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. 2013. Hypersusceptibility mechanism of tenofovir-resistant HIV to EFdA. Retrovirology 10:65. 10.1186/1742-4690-10-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turner D, Brenner B, Wainberg MA. 2003. Multiple effects of the M184V resistance mutation in the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:979–981. 10.1128/CDLI.10.6.979-981.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jochmans D, Van Gimderen M, De Baere I, Dehertogh P, Hallenberger S, Hertogs K. 2006. XV International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop: Basic Principles & Clinical Implications. The in vitro resistance profile of NcRTI is complementary with the resistance profile of tenofovir and zidovudine. Antivir. Ther. 11(Suppl 1):S21 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ly JK, Margot NA, MacArthur HL, Hung M, Miller MD, White KL. 2007. The balance between NRTI discrimination and excision drives the susceptibility of HIV-1 RT mutants K65R, M184V and K65r+M184V. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 18:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.White KL, Margot NA, Ly JK, Chen JM, Ray AS, Pavelko M, Wang R, McDermott M, Swaminathan S, Miller MD. 2005. A combination of decreased NRTI incorporation and decreased excision determines the resistance profile of HIV-1 K65R RT. AIDS 19:1751–1760. 10.1097/01.aids.0000189851.21441.f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buckheit RW., Jr 2004. Understanding HIV resistance, fitness, replication capacity and compensation: targeting viral fitness as a therapeutic strategy. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 13:933–958. 10.1517/13543784.13.8.933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu HT, Colby-Germinario SP, Asahchop EL, Oliveira M, McCallum M, Schader SM, Han Y, Quan Y, Sarafianos SG, Wainberg MA. 2013. Effect of mutations at position E138 in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and their interactions with the M184I mutation on defining patterns of resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors rilpivirine and etravirine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:3100–3109. 10.1128/AAC.00348-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu HT, Oliveira M, Quashie PK, McCallum M, Han Y, Quan Y, Brenner BG, Wainberg MA. 2012. Subunit-selective mutational analysis and tissue culture evaluations of the interactions of the E138K and M184I mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 86:8422–8431. 10.1128/JVI.00271-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sturino CF, Bousquet Y, James CA, DeRoy P, Duplessis M, Edwards PJ, Halmos T, Minville J, Morency L, Morin S, Thavonekham B, Tremblay M, Duan J, Ribadeneira M, Garneau M, Pelletier A, Tremblay S, Lamorte L, Bethell R, Cordingley MG, Rajotte D, Simoneau B. 2013. Identification of potent and orally bioavailable nucleotide competing reverse transcriptase inhibitors: in vitro and in vivo optimization of a series of benzofurano[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2-one derived inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23:3967–3975. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.WHO. 2013. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/en/ Accessed 10 January 2014 [Google Scholar]