Abstract

A number of bivalve species worldwide, including the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, have been affected by mass mortality events associated with herpesviruses, resulting in significant losses. A particular herpesvirus was purified from naturally infected larval Pacific oysters, and its genome was completely sequenced. This virus has been classified as Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) within the family Malacoherpesviridae. Since 2008, mass mortality outbreaks among C. gigas in Europe have been related to the detection of a variant of OsHV-1 called μVar. Additional data are necessary to better describe mortality events in relation to environmental-parameter fluctuations and OsHV-1 detection. For this purpose, a single batch of Pacific oyster spat was deployed in 4 different locations in the Marennes-Oleron area (France): an oyster pond (“claire”), a shellfish nursery, and two locations in the field. Mortality rates were recorded based on regular observation, and samples were collected to search for and quantify OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR. Although similar massive mortality rates were reported at the 4 sites, mortality was detected earlier in the pond and in the nursery than at both field sites. This difference may be related to earlier increases in water temperature. Mass mortality was observed among oysters a few days after increases in the number of PCR-positive oysters and viral-DNA amounts were recorded. An initial increment in the number of PCR-positive oysters was reported at both field sites during the survey in the absence of significant mortality. During this period, the water temperature was below 16°C.

INTRODUCTION

Since the first report by Farley et al. (1), herpesviruses have been associated worldwide with mortality events resulting in significant losses in a number of bivalve species, including the Pacific cupped oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in both hatcheries/nurseries and the natural environment (2–11). A herpesvirus was purified from naturally infected larval Pacific cupped oysters collected in 1995 in a French commercial hatchery (12). Its genome was completely sequenced (13), and the virus was classified as Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) within the family Malacoherpesviridae (14, 15). Moreover, since 2008, mass mortality outbreaks among Pacific cupped oysters have been reported in Europe, including France, Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the United Kingdom (16–23), in relation to the detection of a particular genotype of OsHV-1 called μVar (24).

A protocol based on the intramuscular injection of 0.22-μm-filtered tissue homogenates prepared from naturally infected spat was developed (25). The results of experimental trials showed that mortality was induced after the injection. Furthermore, analysis of injected oyster spat revealed large amounts of OsHV-1 DNA by real-time quantitative PCR. In this context, OsHV-1 was inferred to be the causative agent of the mortality reported in the study (25). In addition to transmitting OsHV-1 infection by intramuscular inoculation, waterborne transmission to healthy oyster spat can also occur via cohabitation of healthy oyster spat with experimentally infected individuals (26). However, the demonstration of a causal link between a pathogen and mortality outbreaks in the field may not be exclusively based on the possibility of reproducing the disease experimentally but should take into account the idea that the cause of mortality outbreaks may be a combination of factors. A causal link between OsHV-1 infection and oyster spat mortality has been suggested in different epidemiological studies (27–29).

In this context, more data are needed in order to better describe mortality events in relation to environmental-parameter fluctuations and OsHV-1 detection. For this purpose, a single batch of Pacific oyster spat was deployed in 4 different locations in the Marennes-Oleron area (Charente Maritime, France): an oyster pond (“claire”), a shellfish nursery, and two locations in the field. Mortality rates were recorded based on regular observation, and samples were collected to search for and quantify OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR. Oyster samples were collected with great frequency during the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oysters and experimental design.

Pacific oysters (C. gigas) were supplied by a shellfish farmer from the Marennes-Oleron area (France). They had been collected in the field (local stock; diploid oyster spat collected in the natural environment) during the summer of 2009 at La Moucliere (Charente estuary, France). For the purpose of the study, wild-caught oysters were deployed in 4 selected locations in the Marennes-Oleron area—a pond (Centre Régional d'Expérimentation et d'Application Aquacole [CREAA]); a shellfish nursery (CREAA); and two sites in the field, La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are (Marennes-Oleron area) (Fig. 1)—in April 2010. They were 8 months old and 6 mm long at the time of deployment. They had not suffered from mortality prior to their deployment in the 4 sites. The Marennes-Oleron area is a major oyster-farming area, accounting for ∼25% of French Pacific oyster (C. gigas) production. It is also one of the two main sites for wild-spat collection in France.

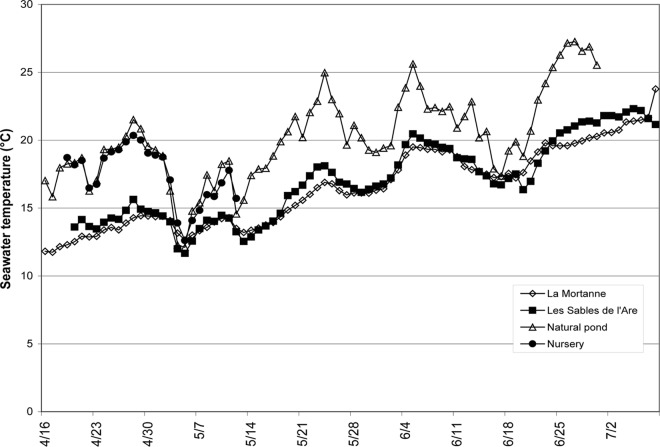

FIG 1.

Map of the Marenne Oléron basin and locations of the test sites. Map created using ArcGIS version 10.2 (ESRI).

Animals transferred to both field sites (Fig. 1) were maintained in 4 mesh oyster bags and 1 oyster rack per site at an initial density of 1,500 individuals per bag and 10,000 oysters per rack. One mesh oyster bag and 1 oyster rack at an initial density of 1,500 individuals per bag and 10,000 oysters per rack were placed in the pond (Fig. 1) and 1 mesh bag in the nursery facilities at an initial density of 20,000 animals (Fig. 1).

Mortality records and sample collection.

Prior to deployment in the different locations, spat (n = 10) were sampled and tested for OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR. Until their deployment in April 2010, the oysters had not been affected by mortality. The day on which the spat arrived at the sites was considered day 0: 16 April for the pond and 19 April for the other 3 sites (La Mortanne, Les Sables de l'Are, and the nursery) (Fig. 1).

Mortality was recorded on different dates, depending on the site. To define mortality rates, 50 animals were collected 3 times in the same experimental unit (bag or rack, depending on the site) on each selected date. Live and dead oysters were counted to determine mortality (average and standard deviation of 3 values). Dead oysters were not removed from the experimental units.

Spat samples were collected (n = 10 per sampling day) in order to detect and quantify OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR. For both field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are) (Fig. 1), samples were collected twice a week from 22 April to 8 July. However, oysters were sampled daily during 3 periods considered risky in terms of mortality: from 26 April to 30 April, from 23 May to 27 May, and from 31 May to 7 June. These periods corresponded to intervals during which a rapid increase in the water temperature (2.5°C in 4 days) had been reported and/or a threshold of 16°C was reached. They were defined based on temperature information regularly collected by Ifremer and on the official MétéoFrance weather forecast. For oysters reared in the pond (“claire”), samples were collected with similar frequency on 31 occasions from 19 April to 7 June 2010. Spat reared in the nursery were sampled on only 10 occasions from 22 April to 12 May 2010 due to rapid mortality.

The water temperature was also recorded during the study using probes (Onset UBTI-001) placed in one of the oyster bags deployed at selected sites.

OsHV-1 DNA detection.

Analyses were carried out by Genindexe (La Rochelle, France), a laboratory officially recognized by national authorities (the French Ministry of Agriculture) for OsHV-1 detection in C. gigas. The laboratory takes part in a yearly proficiency test (interlaboratory comparison) organized by the national reference laboratory for marine mollusc diseases (Ifremer, La Tremblade, France). It was chosen to collect samples with very great frequency during the trial (around 30 dates of collection) and to conduct OsHV-1 DNA detection individually on 10 oysters for each sample date and site. More than 1,000 real-time PCR analyses were carried out. The detection and quantification of OsHV-1 DNA was carried out using a previously published real-time PCR protocol (30). Briefly, the protocol used SYBR green chemistry with specific primers, DPFor/DPRev, targeting the region of the OsHV-1 genome predicted to encode a DNA polymerase catalytic subunit (31). The specificity of the PCR products was systematically confirmed based on the melting-temperature value calculated from the dissociation curve. Melting curves were plotted (55 to 95°C) in order to ensure that a single specific PCR product was amplified. The results were expressed as the viral-DNA copy number mg wet tissue−1.

RESULTS

Water temperature and oyster mortality.

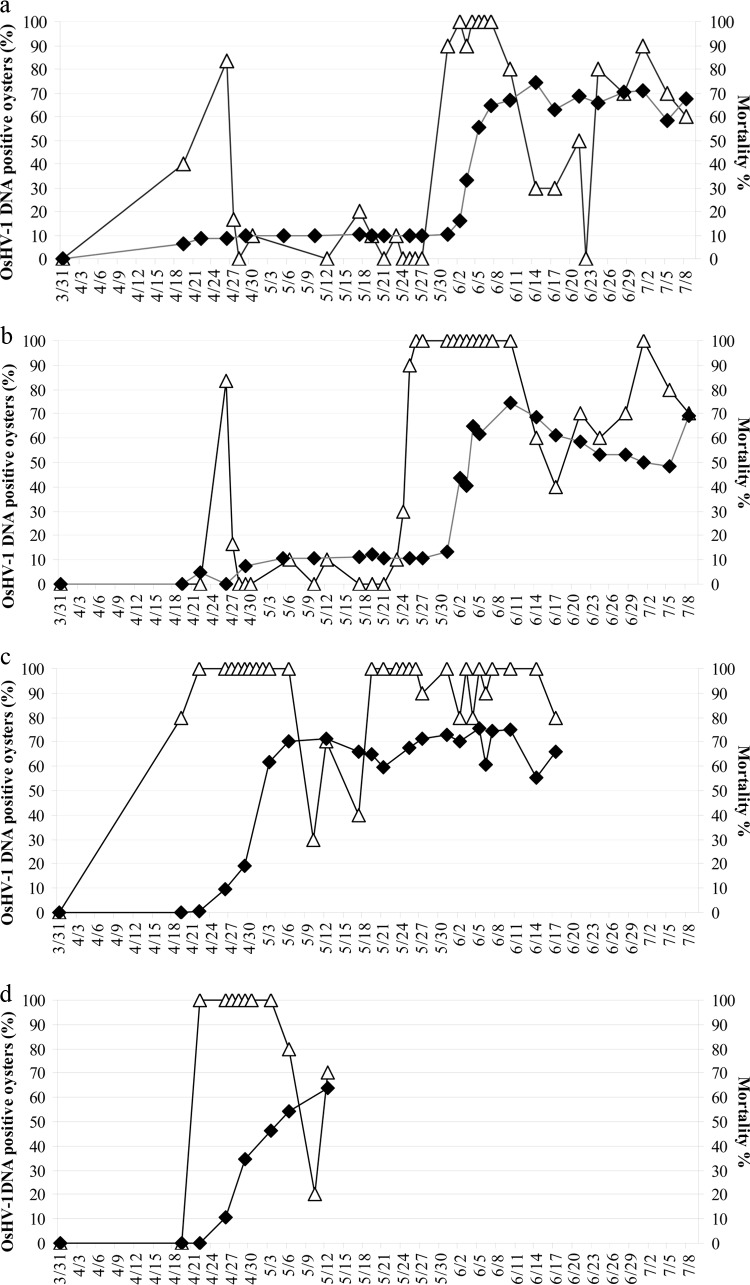

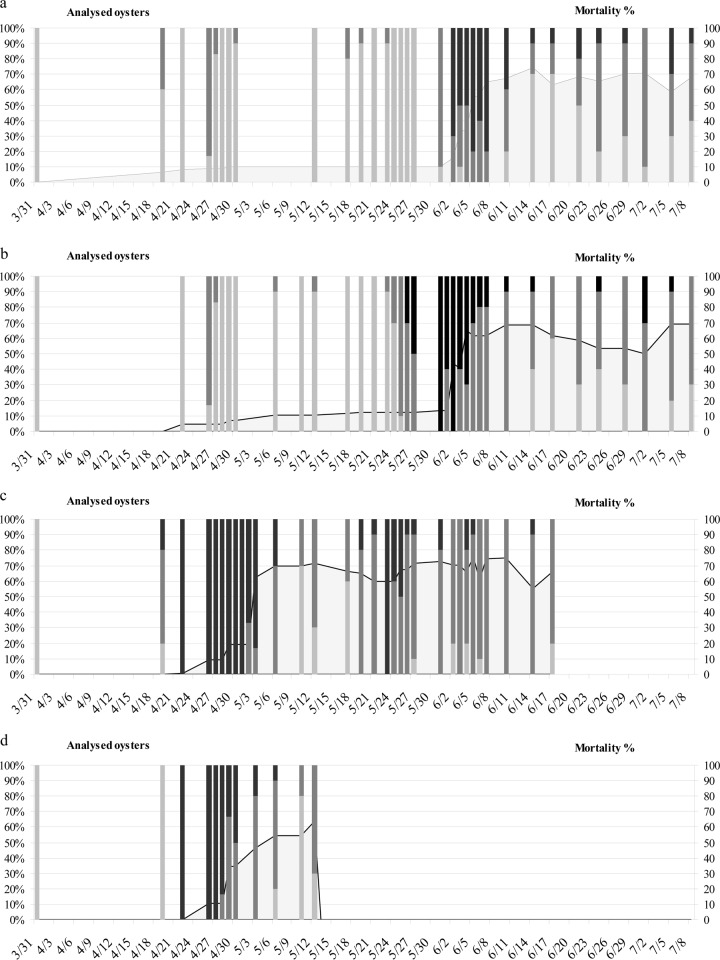

Water temperature variations at all 4 sites are given in Fig. 2. A rapid increase in spat mortality rates was observed from 2 to 15 June and from 5 to 11 June at La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are, respectively (Fig. 3a and b). The mortality rate was 64.7% ± 10.3% at La Mortanne on 7 June and 61.9% ± 0.94% at Les Sables de l'Are on 5 June. The mortality rates remained stable until the end of the study on 7 July 2010 (Fig. 3a and b).

FIG 2.

Daily water temperatures during the survey at the different sites: La Mortanne, Les Sables de l'Are, the natural pond, and the nursery (Charente Martime, France).

FIG 3.

Percentages of OsHV-1 DNA-positive oysters by real-time PCR (△) and mortality percentages (◆) at the different sites (Charente Maritime, France) (standard deviations are not shown to render the graphs more readable). (a) La Mortanne (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 8 July. (b) Les Sables de l'Are (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 8 July. (c) Natural pond (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 17 June. (d) Nursery (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 12 May.

For oysters reared in the pond and in the nursery, mortality rates increased from 0% to 10% from 22 April to 26 April, day 7 after spat deployment (Fig. 3c and d). The water temperature was around 19°C during this period. Three days later, mortality rates in the pond and in the nursery reached 19.18% ± 0% and 34.78% ± 0%, respectively. The mortality rates then increased until the end of the experiment on 12 May (63.7% ± 5.31%) for nursery-reared spat and 17 June (66.2% ± 3.27%) for oysters maintained in the pond (Fig. 3c and d).

OsHV-1 DNA detection by real-time PCR.

Spat (n = 10) scored negative for OsHV-1 DNA detection by real-time PCR prior to oyster deployment on 31 March 2010.

(i) Percentages of positive individuals.

At both field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), more than 80% of the analyzed individuals tested positive for viral DNA on 26 April, 7 days after spat deployment (Fig. 3a and b). A decrease in viral-DNA-positive oysters (0 to 10%) was subsequently observed. During this period, the water temperature varied from 11°C to 15°C (Fig. 2). At Les Sables de l'Are and La Mortanne, the water temperature reached 16°C on 20 May and 22 May, respectively (Fig. 2). From these dates onward, the percentages of viral-DNA-positive samples increased rapidly at both field sites, reaching 100% of the analyzed oysters (Fig. 3a and b).

Eighty percent of the spat tested positive for OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR on 19 March 2010, 3 days after the oysters were transferred to the pond (Fig. 3c). On 22 April, viral DNA was detected in 100% of the analyzed individuals at the site (Fig. 3c). This percentage remained stable until mid-June, except for a short period from 10 to 17 May, during which a water temperature decrease was observed (Fig. 2) (between 12°C and 16°C). For nursery-reared oysters, 100% of the analyzed spat tested positive for OsHV-1 DNA by real-time PCR between 22 April and 3 June (Fig. 3d). A water temperature decrease was observed from 4 to 12 May (Fig. 2) (between 12°C and 16°C). During this time, a decrease in viral-DNA-positive samples was also reported (20% to 80%).

(ii) Viral-DNA amounts.

Due to the high variability of viral-DNA detection among oysters, the animals were classified into 3 categories depending on the OsHV-1 DNA quantities: (i) category 0, no viral DNA; (ii) category 1, viral-DNA amounts of less than 104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue; and (iii) category 2, viral-DNA amounts of ≥104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue.

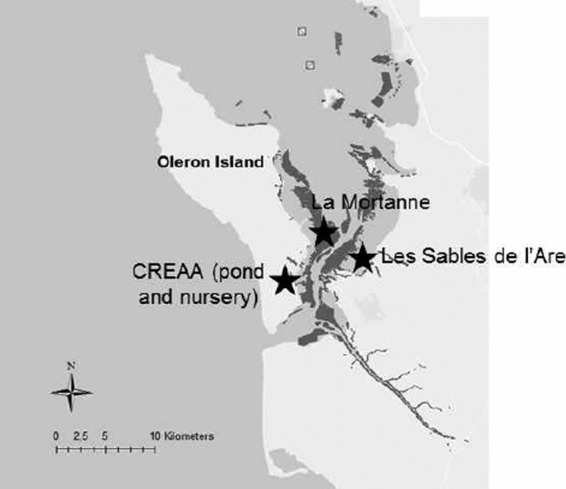

At both field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), viral-DNA amounts remained below 104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue until 31 March to 26 May, a period during which the percentage of OsHV-1-positive individuals was less than 100% (Fig. 4a and b and Table 1). An increase in the percentage of positive animals was reported on 26 April at La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are (Fig. 3a and b and Table 1) without a concomitant increase in the mortality rates. At La Mortanne from 2 to 7 June, viral-DNA amounts of ≥104 DNA copies per mg wet tissue (category 2) were detected in some oysters (Fig. 3a and 4a and Table 1), and mortality rates increased drastically. At Les Sables de l'Are from 27 May to 4 June, viral-DNA amounts of ≥104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue (category 2) were detected in 30% to 100% of the analyzed oysters (Fig. 3b and 4b and Table 1), and mortality rates increased drastically. In the field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), oyster mortality was first reported 1 (3 June) and 7 (2 June) days, respectively, after 100% of the analyzed individuals tested positive for viral DNA, and some oysters showed more than 104 viral-DNA copies per mg of wet tissue.

FIG 4.

Viral-DNA amounts (3 categories: light-gray bars, no viral DNA; dark-gray bars, 0 to 104 viral-DNA copies per mg of wet tissue; black bars, ≥104 copies of viral DNA per mg of wet tissue) detected in oyster spat at the different sites (Charente Maritime, France). Mortality is represented as the gray area below the line. (a) Viral-DNA amounts detected in oysters reared at La Mortanne (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 8 July. (b) Viral-DNA amounts detected in oysters reared at Les Sables de l'Are (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 8 July. (c) Viral-DNA amounts detected in oysters reared in a natural pond (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 17 June. (d) Viral-DNA amounts detected in oysters reared in a nursery (Charente Maritime, France) from 31 March to 12 May.

TABLE 1.

Viral-DNA amounts in oysters collected at the 4 test sites

| Date of sample collection (mo/day) | Amt of viral DNAa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Mortanne | Sables de l'Are | Natural pond | Nursery | |

| 3/31 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 4/19 | 375 | − | 403 | ND |

| 4/22 | ND | ND | 107,356,000 | 10,341,000 |

| 4/26 | 311 | 83 | 57,470,000 | 1,626,800 |

| 4/27 | 1,755 | 17 | 42,460 | 42,560 |

| 4/28 | ND | ND | 1,542,690 | 15,365 |

| 4/29 | ND | ND | 12,515 | 5,357 |

| 4/30 | 1,629 | ND | 6,261,000 | 7,420 |

| 5/1 | − | − | 2,253,500 | − |

| 5/2 | − | − | 264,355 | − |

| 5/3 | − | − | 197,140 | 69 |

| 5/6 | − | 6 | 3,349 | 43 |

| 5/10 | − | ND | 15 | 3 |

| 5/12 | ND | 1 | 5 | 84 |

| 5/17 | 1 | ND | 7 | − |

| 5/19 | 13 | ND | 176 | − |

| 5/21 | ND | ND | 2,163 | − |

| 5/23 | 1,356 | 480 | 3,955 | − |

| 5/24 | ND | 93 | 6,622 | − |

| 5/25 | ND | 152 | 25,161 | − |

| 5/26 | ND | 2,958 | 1,345 | − |

| 5/27 | ND | 21,118 | 187 | − |

| 5/31 | 159 | 5,125,000 | 492 | − |

| 6/1 | − | 170,100 | − | − |

| 6/2 | 671,980 | 4,414,000 | 356 | − |

| 6/3 | 18,100 | 50,580 | 451 | − |

| 6/04 | 11,281 | 220,800 | 1,721 | − |

| 6/5 | 8,398,500 | 2,785 | 157 | − |

| 6/6 | 324,680 | 1,826 | 365 | − |

| 6/7 | 19,680,000 | 277 | 633 | − |

| 6/10 | 102,100 | 292 | 55 | − |

| 6/14 | 264 | 379 | 898 | − |

| 6/17 | 1,025 | 1,343 | 132 | − |

| 6/21 | 898 | 1,217 | − | − |

| 6/24 | 1,408 | 68 | − | − |

| 6/28 | 51 | 2,383 | − | − |

| 7/1 | 42 | 3,853 | − | − |

| 7/5 | 3,048 | 80 | − | − |

| 7/8 | 1,038.2 | 73 | − | − |

Number of genome copies per mg of wet tissue (median values). ND, not detected; −, not determined.

In the oyster pond, an increase (17% to 100%) in oysters with ≥104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue (category 2) was reported from 19 April to 31 May (Fig. 3c and 4c and Table 1). It was followed by an increase in mortality rates (19% on 2 May and 62% on 3 May).

One hundred percent of the nursery-reared oysters tested positive for DNA (22 April to 3 May), and large viral-DNA amounts, from 106 to 108 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue, were detected in some oysters (Fig. 3d and 4d and Table 1). Oyster mortality was first reported on 27 April.

DISCUSSION

Oyster mortality and water temperature.

Although similar mass mortality rates were reported at the 4 test sites (around 65% at the end of the study in July 2010), mortality was detected earlier in the pond and in the nursery than in the field sites. In the field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), oyster mortality increased rapidly from 31 May to 6 June (10% to 60%), 11 and 12 days, respectively, after the water temperature reached 16°C. In the pond and in the nursery, oyster mortality increases were concomitantly detected at the end of April. In both cases, the water temperature was over 16°C at the time of oyster deployment and had reached 20°C when mortality outbreaks started.

Disease outbreaks associated with OsHV-1, including the 2008 to 2012 outbreaks across Europe, have mainly occurred in spring and summer months. However, reports have rarely mentioned specific temperatures. Moreover, there have been only a few experimental studies dealing with the effects of temperature on virus infection (32–34). Le Deuff et al. (33) reported that high water temperatures promote the production of viral particles in association with massive mortality among Pacific oyster larvae. Sauvage et al. (34) indicated that during a disease outbreak reported under laboratory conditions, the mean seawater temperature was 23.8°C, and that the outbreak was preceded by an increase in water temperature of 2.3°C over 2 days. As reported in the present study, a rapid increase in water temperature may thus be considered a critical factor in the disease process. Results from an OsHV-1 survey carried out in France from 1997 to 2006 reported by Garcia et al. (29) supports this hypothesis. Indeed, OsHV-1 detection followed a gradient of increasing temperatures along the French coast, and virus detection could be correlated with a rapid increase in the mean daytime temperature (29). Similar observations have been reported in the field for oyster spat in Tomales Bay in California (3, 27). Temperature extremes above 24 to 25°C were reported before disease outbreaks (3, 27). High seawater temperatures appear to be one of the potential factors likely to induce OsHV-1 infection. This hypothesis is consistent with observations on koi herpesvirus, for which temperatures between 18°C and 28°C favored the onset and severity of disease in fish (35–40). Field surveys conducted in Japan showed that the lowest water temperature at which outbreaks occurred was 15.5°C to 16°C (36, 39). A temperature threshold related to enhanced OsHV-1 expression or mortality appears to be difficult to define precisely. According to the literature, the temperature threshold seems to be site dependent: 22°C to 25°C on the west coast of the United States (3, 27) and 16°C to 20°C in France (41–43). Although the result of viral replication at high temperatures can be a fast spread of the disease to the whole brood and sudden high mortality outbreaks, it is important to keep in mind that infection is not equal to mortality. The high variability of viral-DNA detection between individuals (from 101 to 108 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue) could be due to a nonsynchronous phenomenon. Infected oysters displayed different levels of infection on the same date of collection. Moreover, some oysters may be able to control the viral infection. Although stress (handling, transport, crowding, or modification of feeding) and other environmental parameters have been suggested as important factors in the development of the disease (10, 27–29, 44), in the present study, virus infection occurred at all sites, and its pattern seemed related for the most part to seawater temperature kinetics.

Viral-DNA detection and quantification.

An increase in the number of viral-DNA-positive oysters was detected in late May/early June at both field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), as previously reported at a national level (29). Mass mortality was recorded among oysters a few days after an increase in the number of positive oysters and viral-DNA amounts was noticed. As OsHV-1 was detected prior to mortality events, the virus may be inferred to be the causative agent of oyster spat mortality. Real-time quantitative-PCR analysis revealed the presence of large amounts of OsHV-1 DNA, suggesting that an incubation period occurred with an intense replication phase, leading to irreversible cell damage and mortality (34). Although oyster mortality occurred earlier in the pond and in the nursery than at the field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), large amounts of viral DNA were detected in a large number of oysters prior to the onset of mortality outbreaks. Quantification of viral DNA may constitute a good prognostic marker for the prediction of mortality events. However, due to the high variability of viral-DNA amounts detected among oysters, this parameter does not appear, at an individual level, to be the most informative. Defining categories and using the percentage of individuals in each category could be more useful to define a risk of mass mortality events. It has previously been reported (34, 45) that a number of viral-DNA copies up to 104 may be interpreted as evidence of viral infection leading to mass mortality. In the present study, viral-DNA amounts up to 104 per mg of wet tissue were detected only a few days before mass mortality occurred. The number of positive individuals can also be used as a prediction tool, as 100% of individuals tested positive for OsHV-1 a few days before mass mortality occurred. These results suggest that prior to the onset of mortality, the virus replicated and circulated widely among the oysters, infecting a large number of individuals. The prevalence and viral-DNA quantification have been taken into account for prognosis of vertebrate herpesvirus infections (46, 47). However, real-time PCR did not specify whether viral DNA corresponded to infective viruses (enveloped virus particles), which are necessary to initiate the viral infection in host cells (48). The mean cumulative mortality at the end of the survey was around 65%, and some oyster spat survived. Surviving oysters at the end of the study might represent individuals collected before they died and/or might be considered less susceptible animals. Susceptibility to OsHV-1 infection may vary among oysters, depending on their genetic makeup and on the improved immune and physiological capacities of some animals (34).

Although an initial increase in the number of positive oysters was reported around 26 April at both field sites (La Mortanne and Les Sables de l'Are), viral-DNA amounts detected by real-time PCR remained lower than 104 DNA copies per mg of wet tissue in positive individuals, and no significant mortality increase was detected during this period, when the water temperature was below 16°C. These results suggest that the virus can circulate among oysters and that virus transmission may occur between animals in the absence of mortality events. Two main hypotheses can be proposed in order to explain the high number of positive samples reported in the absence of massive mortality. (i) The conditions encountered by animals in the field might induce stress and viral replication at low levels in healthy-appearing oysters. Arzul et al. (49) have reported the detection of viral DNA in healthy animals and suggested the existence of healthy carriers. In this context, a large number of animals could be healthy carriers at the beginning of the study without viral-DNA detection. The absence of viral-DNA detection could be due to the low number of analyzed animals (10) at the beginning of the study and/or the limits of the protocol used, including undetectable levels of viral DNA. (ii) The high number of positive samples reported in the absence of massive mortality might also be due to virus propagation from an initial source (infected oysters from the batch used in the present study or viruses present in the field). Although data obtained during the survey did not allow us to draw clear conclusions as to the exact virus source, the results suggest that viral contamination could occur among oysters in the absence of mass mortality and when the water temperature is lower than 16°C. Moreover, it is important to note that the number of viral-DNA-positive oysters decreased after mass mortality events. This result may be explained by the death of the most infected/susceptible individuals and also suggests that some oysters may be able to control viral infection under certain conditions.

Improved knowledge about the viral infection process and virus transmission may facilitate the implementation of practical precautions and epidemiological recommendations, which would in turn contribute to reducing the impact of virus contamination of Pacific oysters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially funded through the Région Poitou-Charentes.

We thank Valerie Barbosa-Solomieu for editing and English enhancement.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 June 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Farley CA, Banfield WG, Kasnic JRG, Foster WS. 1972. Oyster herpes-type virus. Science 178:759–760. 10.1126/science.178.4062.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arzul I, Nicolas JL, Davison AJ, Renault T. 2001. French scallops: a new host for Ostreid Herpesvirus-1. Virology 290:342–349. 10.1006/viro.2001.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burge CA, Griffin FJ, Friedman CS. 2006. Mortality and herpesvirus infections of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in Tomales Bay, California, U. S. A. Dis. Aquat. Org. 72:31–43. 10.3354/dao072031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comps M, Cochennec N. 1993. A herpes-like virus from the European oyster Ostrea edulis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 62:201–203. 10.1006/jipa.1993.1098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hine PM, Wesney B, Hay B. 1992. Herpesvirus associated with mortalities among hatchery-reared larval Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas. Dis. Aquat. Org. 12:135–142. 10.3354/dao012135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hine PM, Thorne T. 1997. Replication of herpes-like viruses in haemocytes of adult flat oysters Ostrea angasi (Sowerby 1871): an ultrastructural study. Dis. Aquat. Org. 29:197–204. 10.3354/dao029197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hine PM, Wesney B, Besant P. 1998. Replication of herpes-like viruses in larvae of the flat oyster Tiostrea chilensis at ambient temperatures. Dis. Aquat. Org. 32:161–171. 10.3354/dao032161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolas JL, Comps M, Cochennec N. 1992. Herpes-like virus infecting Pacific oyster larvae, Crassostrea gigas. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 12:11–13 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renault T, Cochennec N, Le Deuff RM, Chollet B. 1994. Herpes-like virus infecting Japanese oyster (Crassostrea gigas) spat. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 14:64–66 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renault T, Le Deuff RM, Cochennec N, Maffart P. 1994. Herpesviruses associated with mortalities among Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in France: comparative study. Rev. Med. Vet. 145:735–742 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renault T, Lipart C, Arzul I. 2001. A herpes-like virus infects a non-ostreid bivalve species: virus replication in Ruditapes philippinarum larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 45:1–7. 10.3354/dao045001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Deuff RM, Renault T. 1999. Purification and partial genome characterization of a herpes-like virus infecting the Japanese oyster, Crassostrea gigas. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1317–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison AJ, Trus BL, Cheng N, Steven AC, Watson MS, Cunningham C, Le Deuff RM, Renault T. 2005. A novel class of herpesvirus with bivalve hosts. J. Gen. Virol. 86:41–53. 10.1099/vir.0.80382-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayard GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AM, Pellett PE, Roizman B, Studdert MJ, Thiry E. 2009. The order Herpesvirales. Arch. Virol. 154:171–177. 10.1007/s00705-008-0278-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minson AC, Davison AJ, Eberle R, Desrosiers RC, Fleckstein B, McGeoch DJ, Pellet PE, Roizman B, Studdert DMJ. 2000. Family Herpesviridae, p 203–225 In Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dundon WG, Arzul I, Omnes E, Robert M, Magnabosco C, Zambon M, Gennari L, Toffan A, Terregino C, Capua I, Arcangeli G. 2011. Detection of Type 1 Ostreid Herpes variant (OsHV-1 μvar) with no associated mortality in French-origin Pacific cupped oyster Crassostrea gigas farmed in Italy. Aquaculture 314:49–52. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). 2010. Scientific opinion on the increased mortality events in Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. EFSA J. 8:1–59 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch SA, Carlson J, Reilly AO, Cotter E, Culloty SC. 2012. A previously undescribed ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) genotype detected in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in Ireland. Parasitology 139:1526–1532. 10.1017/S0031182012000881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martenot C, Oden E, Travaillé E, Malas JP, Houssin M. 2011. Detection of different variants of ostreid herpesvirus 1 in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Virus Res. 160:25–31. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martenot C, Oden E, Travaillé E, Malas JP, Houssin M. 2010. Comparison of two real-time PCR methods for detection of ostreid herpesvirus 1 in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. J. Virol. Methods 70:86–99. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peeler JE, Reese RA, Cheslett DL, Geoghegan F, Power A, Trush MA. 2012. Investigation of mortality in Pacific oysters associated with Ostreid herpesvirus-1 μVar in the Republic of Ireland in 2009. Prev. Vet. Med. 105:136–143. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renault T, Moreau P, Faury N, Pepin JF, Segarra A, Webb S. 2012. Analysis of clinical ostreid herpesvirus 1 (Malacoherpesviridae) specimens by sequencing amplified fragments from three virus genome areas. J. Virol. 86:5942–5947. 10.1128/JVI.06534-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roque A, Carrasco N, Andree KB, Lacuesta B, Elandaloussi L, Gairin I, Rodgers CJ, Furones MD. 2012. First report of OsHV-1 microvar in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) cultured in Spain. Aquaculture 324–325:303–306 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segarra A, Pepin JF, Arzul I, Morga B, Faury N, Renault T. 2010. Detection and description of a particular Ostreid herpesvirus 1 genotype associated with massive mortality outbreaks of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. Virus Res. 153:92–95. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schikorski D, Renault T, Saulnier D, Faury N, Moreau P, Pépin JF. 2011. Experimental infection of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas spat by ostreid herpesvirus 1: demonstration of oyster spat susceptibility. Vet. Res. 42:27–40. 10.1186/1297-9716-42-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schikorski D, Faury N, Pépin JF, Saulnier D, Tourbiez D, Renault T. 2011. Experimental Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) infection of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas: kinetics of virus DNA detection by q-PCR in seawater and in oyster samples. Virus Res. 155:28–34. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burge C, Judah LR, Conquest LL, Griffin FJ, Cheney DP, Suhrbier A, Vadopalas B, Olin PG, Renault T, Friedman CS. 2007. Summer seed mortality of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg grown in Tomales Bay, California, U. S. A.: the influence of oyster stock, planting time, pathogens, and environmental stressors. J. Shellfish Res. 26:163–172 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman CS, Estes RM, Stokes NA, Burge CA, Hargove JS, Barber BJ, Elston RA, Burreson EM, Reece KS. 2005. Herpes virus in juvenile Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas from Tomales Bay, California, coincides with summer mortality episodes. Dis. Aquat. Org. 63:33–41. 10.3354/dao063033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia C, Thébault A, Dégremont L, Arzul I, Miossec L, Robert M, Chollet B, François C, Joly JP, Ferrand S, Kerdudou N, Renault T. 2011. OsHV-1 detection and relationship with C. gigas spat mortality in France between 1998 and 2006. Vet. Res. 42:73–84. 10.1186/1297-9716-42-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pépin JF, Riou A, Renault T. 2008. Rapid and sensitive detection of ostreid herpesvirus 1 in oyster samples by real-time PCR. J. Virol. Methods 149:269–276. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb SC, Fidler A, Renault T. 2007. Primers for PCR-based detection of ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1): application in a survey of New Zealand molluscs. Aquaculture 272(1–4):126–139. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.07.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Deuff RM, Nicolas JL, Renault T, Cochennec N. 1994. Experimental transmission of a herpes-like virus to axenic larvae of Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 14:69–72 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Deuff RM, Renault T, Gérard A. 1996. Effects of temperature on herpes-like virus detection among hatchery-reared larval Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Dis. Aquat. Org. 24:149–157. 10.3354/dao024149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauvage C, Pépin JF, Lapègue S, Boudry P, Renault T. 2009. Ostreid herpes virus 1 infection in families of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, during a summer mortality outbreak: difference in viral DNA detection and quantification using real-time PCR. Virus Res. 142:181–187. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilad O, Yun S, Adkison MA, Way K, Willits NH, Bercovier H, Hedrick RP. 2003. Molecular comparison of isolates of an emerging fish pathogen, koi herpesvirus, and the effect of water temperature on mortality of experimentally infected koi. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2661–2668. 10.1099/vir.0.19323-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hara H, Aikawa H, Usui K, Nakanishi T. 2006. Outbreaks of koi herpesvirus disease in rivers of Kanagawa prefecture. Fish Pathol. 41:81–83. 10.3147/jsfp.41.81 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pokorova D, Vesely T, Piackova V, Reschova S, Hulova J. 2005. Current knowledge on koi herpesvirus (KHV): a review. Vet. Med. Czech. 50:139–147 [Google Scholar]

- 38.St-Hilaire S, Beevers N, Way K, Le Deuff RM, Martin P, Joiner C. 2005. Reactivation of koi herpesvirus infections in common carp Cyprinus carpio. Dis. Aquat. Org. 67:15–23. 10.3354/dao067015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sano M, Ito T, Kurita J, Yanai T, Watanabe N, Miwa S, Iida T. 2004. First detection of koi herpes virus in cultured common carp Cyprinus carpio in Japan. Fish Pathol. 39:165–167. 10.3147/jsfp.39.165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuasa K, Ito T, Sano M. 2008. Effect of water temperature on mortality and virus shedding in carp experimentally infected with koi herpesvirus. Fish Pathol. 43:83–85. 10.3147/jsfp.43.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petton B, Pernet F, Robert R, Boudry P. 2013. Temperature influence on pathogen transmission and subsequent mortalities in juvenile Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas. Aquacult. Environ. Interact. 3:257–273. 10.3354/aei00070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samain JF, McCombie H. 2008. Summer mortality of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas: the Morest project. Editions Quae, Versailles, France [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soletchnik P, Le Moine O, Faury N, Razet D, Geairon P, Goulletquer P. 1999. Mortalité de l'huître Crassostrea gigas dans le bassin de Marennes-Oléon: étude de la variabilité spatiale de son environnement et de sa biologie par un système d'informations géographiques (SIG). Aquat. Living Res. 12:131–143. 10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80022-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbosa-Solomieu V, Dégremont L, Vazquez-Juarez R, Ascencio-Valle F, Boudry P, Renault T. 2005. Ostreid Herpesvirus 1 detection among three successive generations of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Virus Res. 107:47–56. 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oden E, Martenot C, Travaillé E, Malas JP, Houssin M. 2011. Quantification of ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) in Crassostrea gigas by real-time PCR: determination of a viral load threshold to prevent summer mortalities. Aquaculture 317:27–31. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Islam AFM, Walkden-Brown SW, Islam A, Underwood GJ, Groves PJ. 2006. Relationship between Marek's disease virus load in peripheral blood lymphocytes at various stages of infection and clinic Marek's disease in broiler chickens. Avian Pathol. 35:42–48. 10.1080/03079450500465734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hudnall SD, Chen T, Allison P, Tyring SK, Heath A. 2008. Herpesvirus prevalence and viral load in healthy blood donors by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Transfusion 48:1180–1187. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyman MG, Enquist LW. 2009. Herpesvirus interactions with the host cytoskeleton. J. Virol. 83:2058–2066. 10.1128/JVI.01718-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arzul I, Renault T, Thébault A, Gérard A. 2002. Detection of oyster herpesvirus DNA and proteins in asymptomatic Crassostrea gigas adults. Virus Res. 84:151–160. 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00007-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]