Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance issues have become a global health concern. The rapid identification of multidrug-resistant microbes, which depends on microbial genomic information, is essential for overcoming growing antimicrobial resistance challenges. However, genotyping methods, such as multilocus sequence typing (MLST), for identifying international epidemic clones of Acinetobacter baumannii are not easily performed as routine tests in ordinary clinical laboratories. In this study, we aimed to develop a novel genotyping method that can be performed in ordinary microbiology laboratories. Several open reading frames (ORFs) specific to certain bacterial genetic lineages or species, together with their unique distribution patterns on the chromosomes showing a good correlation with the results of MLST, were selected in A. baumannii and other Acinetobacter spp. by comparing their genomic data. The distribution patterns of the ORFs were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis after multiplex PCR amplification and digitized. A. baumannii sequence types (STs) corresponding to international clones I and II were successfully discriminated from other STs and Acinetobacter species by detecting the distribution patterns of their ORFs using the multiplex PCR developed here. Since bacterial STs can be easily expressed as digitized numeric data with plus (+) expressed as 1 and minus (−) expressed as 0, the results of the method can be easily compared with those obtained by different tests or laboratories. This PCR-based ORF typing (POT) method can easily and rapidly identify international epidemic clones of A. baumannii and differentiate this microbe from other Acinetobacter spp. Since this POT method is easy enough to be performed even in ordinary clinical laboratories, it would also contribute to daily infection control measures and surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance has become a global health concern. The World Health Organization has stated that weak or absent antimicrobial resistance surveillance and monitoring systems accelerate the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (see http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ ). One of the weak points of current antimicrobial resistance surveillance and monitoring systems is the absence of genetic data for the bacterial isolates. Microbial genotyping is indispensable for a precise understanding of the genetic lineages of clinical isolates that cause nosocomial outbreaks (1).

Acinetobacter baumannii is one of the major multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogens. In particular, A. baumannii epidemic clones, the so-called international clones I and II, usually show multidrug resistance, and only limited antimicrobials are efficacious for treating infections caused by them (2). On the other hand, A. baumannii clinical isolates other than the epidemic international clones are still susceptible to several antimicrobials. The performance of appropriate precautions that target the epidemic clones is indispensable for blocking their further nosocomial transmission. Therefore, it has become very important to rapidly discriminate the A. baumannii epidemic clones from other nonepidemic A. baumannii lineages and non-baumannii Acinetobacter species, such as Acinetobacter nosocomialis and Acinetobacter pittii. In this regard, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is indeed useful for the exact identification of the epidemic clones, which are classified into several sequence types (STs), such as ST1 and ST2, by MLST performed at the Institut Pasteur. ST1 and ST2 are also assigned to clonal complex 109 (CC109) and CC92, respectively, by the MLST of Bartual et al. (19) as reported by Zarrilli et al. (3) However, MLST of Acinetobacter clinical isolates can be performed only in limited cases of nosocomial outbreaks even in Japan, and this results in a delay in the ability to alert for the emergence and spread of epidemic clones in hospital settings. Early identification of epidemic clones of A. baumannii is very important especially in the areas where they have not been prevalent yet. Therefore, the establishment of easy and rapid genotyping methods has been much awaited.

The construction of new analytical methods that make it easy to obtain genetic information of clinical isolates in ordinary clinical laboratories is desired. We consider that the most convenient way to simplify microbial genotyping would be to display the results as “1” for “+” and “0” for “−”, the so-called binary typing, which does not require any further handling of specimens, such as performing nucleotide sequence analyses, counting the allelic repeats, or analyzing complicated restriction enzyme digestion patterns. We previously succeeded in developing a genotyping method for Staphylococcus aureus by detecting the distribution patterns of its open reading frames (ORFs) using multiplex PCR that can be replaced with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (4, 5). In the genotyping of S. aureus, the distribution patterns of small genomic islets (SGIs) showed good correlations with the clonal complex (CC) types obtained by MLST. SGIs consist of one to several ORFs (6). Therefore, we hypothesized that the CCs of A. baumannii and the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex might be also estimated or predicted by detecting the distribution patterns of SGIs specific to each Acinetobacter species. The distribution patterns of SGIs can easily be visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis after multiplex PCR; therefore, clone typing of isolates can be performed in many ordinary microbiology laboratories in which equipment for only PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis is available.

In the present study, therefore, we developed a new multiplex PCR-based method for easy, rapid, and reliable discrimination of the clonal complexes of A. baumannii, especially the epidemic clones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 226 Acinetobacter clinical isolates collected from patients in Japan between 2001 and 2012, including 79 A. baumannii, 20 A. pittii, 77 A. nosocomialis, 15 Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis, 24 A. radioresistens, three A. ursingii, three A. bereziniae, two A. soli, one A. junii, one Acinetobacter genomic species 13BJ, and one Acinetobacter genomic species 14BJ, were used. These isolates were identified using their rpoB gene sequence (7). Two American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) reference strains available in our laboratory (A. baumannii strains ATCC 19606 and ATCC BAA-1605) were also used. The 79 A. baumannii clinical isolates and two ATCC reference strains were analyzed by MLST. The isolates were cultured overnight on soy bean casein digest agar plates at 37°C, and chromosomal DNA was extracted with the QuickGene SP kit DNA tissue (SP-DT) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). MLST analysis was performed according to the protocol of the Institut Pasteur MLST databases (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst). The clustering of related STs, which was defined as a CC, was determined with the aid of the eBURST program (http://eburst.mlst.net/).

For Acinetobacter-specific ORF screening, Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain JCM 14847, Pseudomonas putida strain JCM 13063, Pseudomonas fluorescens strain JCM 5963, Pseudomonas stutzeri strain JCM 5965, Pseudomonas nitroreducens strain JCM 2782, Azotobacter vinelandii strain JCM 21475, and Brevundimonas diminuta strain JCM 2788 were used as a negative control. These strains were provided by the Japan Collection of Microorganisms, Riken BioResource Center (BRC), which participates in the National BioResource Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT). Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Escherichia coli clinical isolates were also used as a negative control.

Searching small genomic islets from A. baumannii whole-genome sequences.

The whole-genome DNA sequences of six A. baumannii strains, AB0057 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. CP001182), AB307-0294 (GenBank accession no. CP001172), AYE (GenBank accession no. CU459141), ACICU (GenBank accession no. CP000863), ATCC 17978 (GenBank accession no. CP000521), and SDF (GenBank accession no. CU468230), were obtained from an Internet database (PubMed [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez]) and compared to each other using the MBGD website (http://mbgd.genome.ad.jp/) and blast+ (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA), with a tabular output option, and homologues were visualized by ACT (8). The nonconserved regions among the six strains were identified and selected as potential SGIs. Among the selected SGIs, those containing single to several ORFs without the presence of structures resembling insertion sequences, transposases, or integrases were selected for the determination of CCs. Nonconserved regions with larger structures, such as transposons, prophages, and antimicrobial resistance islands, were excluded. The distribution patterns of the SGI candidates (Table 1) were investigated by PCR using 42 A. baumannii representative clinical isolates and two ATCC strains.

TABLE 1.

ORF candidates relating to small genomic islets (SGI) and their distributions among the A. baumannii genomesa

| SGI ORF candidateb | ORF corresponding to the SGI ORF candidates among the indicated A. baumannii strain (Pasteur sequence type, GenBank accession no.)c |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB0057 (ST1, CP001182) | ACICU (ST2, CP000863) | ATCC17978 (ST77slvd, CP000521) | SDF (ST17, CU468230) | |

| ACICU_00180* | ACICU_00180 (100) | A1S_0157 (99) | ||

| AB57_0388* | AB57_0388 (100) | |||

| AB57_0454* | AB57_0454 (100) | Between A1S_0376e and A1S_0378 (99) | Between ABSDF3133 and ABSDF3134 (98) | |

| AB57_0526 | AB57_0526 (100) | Between ABSDF 3067 and ABSDF3068 (99) | ||

| ACICU_00563* | ACICU_00563 (100) | ABSDF2963 (100) | ||

| AB57_0815*# | AB57_0815 (100) | A1S_0767 (99) | ||

| AB57_1987 | AB57_1987 (100) | ACICU_01794 (99) | ABSDF1977 (98) | |

| AB57_2085 | AB57_2085 (100) | Between A1S_1754 and A1S_1755 (96) | ||

| ACICU_01870*# | ACICU_01870 (100) | A1S_1782 (95) | ABSDF1960 (96) | |

| ACICU_02042 *# | ACICU_02042 (100) | A1S_1927 (99) | ||

| AB57_2484*# | AB57_2484 (100) | ACICU_02351 (98) | ||

| ACICU_02468 | ACICU_02468 (100) | A1S_2266 (99) | ABSDF1260 (97) | |

| ACICU_02520* | Between AB57_2751 and AB57_2752 (99) | ACICU_02520 (100) | Between A1S_2318 and A1S_2319 (99) | |

| ACICU_02597 | ACICU_02597 (100) | |||

| AB57_2930 | AB57_2930 (100) | ACICU_02697 (99) | A1S_2485 (98) | |

| ACICU_02886 | AB57_3056 (96) | ACICU_02886 (100) | A1S_2641 (97) | |

| ACICU_02966*# | ACICU_02966 (100) | Between A1S_2707 and A1S_2708 (98) | ABSDF0764 (98) | |

| AB57_3308*# | AB57_3308 (100) | |||

| ACICU_03137*# | ACICU_03137 (100) | ABSDF0546 (98) | ||

| AB57_3624* | AB57_3624 (100) | ACICU_03369 (99) | Between A1S_3168 and A1S_3169 (99) | |

| ACICU_03379* | ACICU_03379 (100) | ABSDF0314 (95) | ||

| ACICU_03418* | ACICU_03418 (100) | Between A1S_3220 and A1S_3221 (99) | ABSDF0260 (100) | |

| A1S_3257 | A1S_3257 (100) | ABSDF3356 (98) | ||

| ACICU_03581* | ACICU_03581 (100) | A1S_3381 (99) | ABSDF3529 (99) | |

SGI, small genomic islet.

ORFs showing the same distribution patterns among clonal isolates are indicated by an asterisk (*), and ORFs selected for PCR-based ORF typing are indicated by a hash tag (#).

Numbers in parentheses are the percent sequence similarities over representative SGI ORFs listed in the first column.

slv, single locus variant.

When nucleotide sequences corresponding to an SGI ORF candidate are found in the genomes of some A. baumannii strains but they have not been named in the annotated genome data, the ORFs flanking the nucleotide sequence similar to the SGI ORF candidate are provided.

Searching species-specific ORFs from whole-genome sequences.

The whole-genome DNA sequences of four A. pittii (strains D499 [GenBank accession no. AGFH00000000], DSM 9306 [AIEF00000000], DSM 21653 [AIEK00000000], and SH024 [NZ_ADCH00000000]), two A. nosocomialis (strains NCTC 8102 [AIEJ00000000] and RUH2624 [NZ_ACQF00000000]), three Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (strains PHEA-2 [CP002177], DSM 30006 [NZ_APQI00000000], and RUH2202 [NZ_ACPK00000000]), one A. bereziniae (strain LMG 1003 [NZ_AIEI00000000]), one Acinetobacter haemolyticus (strain ATCC 19194 [NZ_ADMT00000000]), one Acinetobacter johnsonii (strain SH046 [NZ_ACPL00000000]), one A. junii (strain SH025 [NZ_ACPM00000000]), three Acinetobacter lwoffii (strains NCTC 5866 [AIEL00000000], SH145 [NZ_ACPN00000000], and WJ10621 [NZ_AFQY00000000]), one Acinetobacter parvus (strain DSM 16617 [AIEB00000000]), four A. radioresistens (strains DSM 6976 [AIDZ00000000], SH164 [NZ_ACPO00000000], SK82 [NZ_ACVR00000000], and WC-A-157 [ALIR00000000]), one A. ursingii (strain DSM 16037 [AIEA00000000]), one Acinetobacter venetianus (strain RAG-1 [AKIQ00000000]), and four Acinetobacter species that have not been given scientific names (GG2 [ALOW00000000], ATCC 27244 [ABYN00000000], HA [NZ_AJXD00000000], and NBRC 100985 [NZ_BAEB00000000]) and the genomic data of six A. baumannii isolates mentioned in the section above were obtained from PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez) and compared using blast+. ORFs showing high percent sequence similarities among all Acinetobacter species used in the method were selected as candidates of markers specific to Acinetobacter species. ORFs found only in A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, or Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis (corresponding to strain GG2) genomes were selected as candidates of species-specific ORFs (Table 2). The presence of species-specific ORFs was screened by PCR for representative isolates, including eight A. baumannii, four A. pittii, eight A. nosocomialis, and four Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis.

TABLE 2.

Species-specific ORF candidates

| ORFa | Contig no., nucleotide positionb | No. found/no. tested for Acinetobacter organism: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii | A. pittii | A. nosocomialis | Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis | Other Acinetobacter species | ||

| pittii-1 | 9, 490–1095 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NTc |

| pittii-2 | 19, 296023–297078 | 0/8 | 3/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| pittii-3 | 21, 113290–112808 | 5/8 | 2/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| pittii-4 | 23, 336772–337306 | 5/8 | 3/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| pittii-5 | 23, 435468–436845 | 0/8 | 2/4 | 1/8 | 4/4 | NT |

| pittii-6* | 25, 270084–271118 | 0/81 | 19/20 | 0/77 | 0/15 | 0/35 |

| pittii-7 | 26, 56553–57056 | 0/8 | 2/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| pittii-8 | 31, 96908–97756 | 0/8 | 3/4 | 0/8 | 1/4 | NT |

| pittii-9 | 31, 288435–286909 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 1/4 | NT |

| nosocomialis-1 | 6, 48398–49115 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 7/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| nosocomialis-2 | 12, 64890–63445 | 8/8 | 0/4 | 8/8 | 1/4 | NT |

| nosocomialis-3* | 90, 13009–11208 | 0/81 | 0/20 | 76/77 | 0/15 | 0/35 |

| Asp-1* | 12, 41330–40363 | 0/81 | 0/20 | 0/77 | 15/15 | 0/35 |

| Asp-2 | 15, 52010–54341 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| Asp-3 | 15, 207828–209480 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

| Asp-4 | 16, 155456–156670 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 1/4 | NT |

| Asp-5 | 21, 98536–99348 | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 0/4 | NT |

The ORFs selected for species identification are indicated by an asterisk.

ORFs were selected from A. pittii D499 (pittii-1 to -9 [GenBank accession no. AGFH00000000]), A. nosocomialis NCTC 8102 (nosocomialis-1 to -3 [GenBank accession no. AIEJ00000000]), and Acinetobacter species GG2 (Asp-1 to -5 [GenBank accession no. ALOW00000000]).

NT, not tested.

Multiplex PCR detection of selected ORFs to identify international clones.

To maximize the discriminatory power and reliability of the identification of international clones, seven ORFs in separate SGIs were selected for multiplex PCR detection in order to identify international clones with a minimum difference of two bands in the detected ORF ladder patterns of other CCs among the isolates used in this study (Table 1).

For easy execution, the selected ORFs were detected by multiplex PCR, which we call PCR-based ORF typing (POT). The primer pairs for detecting ORFs in the seven SGIs, Acinetobacter-specific ORF, blaOXA-51 (9), and three species-specific ORFs (Table 2) were designed for multiplex PCR detection (Table 3). As ORFs in SGIs were found among A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter spp. close to A. nosocomialis, as well as for A. baumannii, the primers were designed to adapt universally to those Acinetobacter species.

TABLE 3.

Primers finally selected for multiplex PCR

| Target ORF | Primer direction | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Final concn (μM) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atpA | Forward | CTGAACCTAGAACAGGATTCAGT | 0.2 | 553 |

| Reverse | TCACGGAAGTATTCACCCAT | 0.2 | ||

| OXA-51 | Forward | GCTTCGACCTTCAAAATGCT | 0.2 | 465 |

| Reverse | TCCAGTTAACCAGCCTACTTGT | 0.2 | ||

| pittii-6 | Forward | CATGTAGGTAGTCAAATGCCTG | 0.2 | 401 |

| Reverse | CCGCTGGTGATGCTTTATTC | 0.2 | ||

| nosocomialis-3 | Forward | GTGATCGTGGTGATAGCTGG | 0.2 | 362 |

| Reverse | GTAAGTTCCTGTTGCAACTCC | 0.2 | ||

| Asp-1 | Forward | GGATCTTTAACTCCATGGCTC | 0.2 | 321 |

| Reverse | GATTATCrTGTAATAACCACGCAC | 0.2 | ||

| AB57_2484 | Forward | TATGTACAAAGCCAACCGGA | 0.2 | 271 |

| Reverse | GAATTTGAGCdGAAGCCATTA | 0.2 | ||

| ACICU_02042 | Forward 1 | CCGCGTCTTTCATAATAAGCAA | 0.1 | 234 |

| Forward 2 | CCACGTCTCTCATAATAAGCAA | 0.1 | ||

| Reverse 1 | TGGAGAAATAGATTCTTCAAAAGTTGT | 0.1 | ||

| Reverse 2 | TGCAGAAATAGATTCTTCAmAAATTGT | 0.1 | ||

| ACICU_02966 | Forward | ACCGTAyCCCTTTTTAATAAGTTCA | 0.2 | 189 |

| Reverse | GGGCAAACTTATCATAGTTATATCGAC | 0.2 | ||

| ACICU_01870 | Forward | GCTGCAACCCAACCAATwA | 0.2 | 151 |

| Reverse | AATTGGCTTCGhTGGATATTTATG | 0.2 | ||

| AB57_3308 | Forward | GCAACAGTTTCAAAATTAAATGG | 0.2 | 122 |

| Reverse 1 | ACTGTTTGTATGGGTATTGCAG | 0.1 | ||

| Reverse 2 | ACTGTTTGTATAGGCATTGCAG | 0.1 | ||

| ACICU_03137 | Forward | CCyGCACTGCTCTACGATAATG | 0.2 | 102 |

| Reverse | TTGyTCATAATGAAAAGCCGCA | 0.2 | ||

| AB57_0815 | Forward | CTTTAGAmGAGGCACGTTGGTTTG | 0.2 | 81 |

| Reverse | TTTCACAyGGCTCACCGT | 0.2 |

Mixed nucleotide residues were described according to a standard code (r, A/G; d, A/G/T; m, A/C; y, C/T; w, A/T; h, A/C/T).

Template DNAs for multiplex PCR were prepared by suspending bacterial cells in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at a turbidity of McFarland standard 0.5 to 2, heating at 100°C for 10 min, and centrifugation at 14,000 rpm (approximately 15,000 × g) for 1 min. Next, POT was carried out with the four thermal cyclers, i.e., GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Life Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan), Applied Biosystems 2720 (Life Technologies Japan), GeneAtlas 322 (Astec, Fukuoka, Japan), and the Thermal Cycler Dice Gradient (TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Japan), to validate their compatibility on the same platforms. The primer mixture was prepared by mixing all primers listed in Table 3 to 100× the final concentration. PCR was carried out in a 20-μl mixture containing 2 μl of the heat extract template DNA, prepared as described above, PCR buffer (3 mM Mg2+), 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.8 units of FastStart Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and 0.2 μl of the primer mixture. The sequences and final concentrations of the primers are shown in Table 3. All four DNA preparations extracted from clinical A. baumannii (POT 122 [ST2] in Table 4), A. pittii (POT 78 in Table 4), A. nosocomialis (POT 105 in Table 4), and Acinetobacter spp. close to A. nosocomialis (POT 105 in Table 4) were mixed and used as the DNA template for both the positive control and the ladder marker in PCR. The thermal conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 30 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min, and then at 4°C for several hours before agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products (2 μl) were electrophoresed on 4% agarose gels (NuSieve 3:1; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) at 100 V for 50 min; the bands were then visualized with ethidium bromide.

TABLE 4.

Correlations between MLST and ORFs used for POT

| POT no. | ST (CC or allele profile) | No. of isolates | Presence or absence of ORFs for the POT analysis by group: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORFs for identification of bacterial speciesa |

ORFs for calculation of POT no.b |

|||||||||||||

| atpA | OXA-51 | pittii-6 | nosocomialis-3 | Asp-1 | AB57_2484 | ACICU_02042 | ACICU_02966 | ACICU_01870 | AB57_3308 | ACICU_03137 | AB57_0815 | |||

| A. baumannii | ||||||||||||||

| 122 | ST2 (CC2) | 27 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| 69 | ST1 (CC1) | 3 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| 0 | ST235 (CC33) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | ST33 (CC33) | 18 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 8 | ST148 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 32 | CC33 (3-5-7-1-12-1-2) | 2 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 32 | ST239 (CC216) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 44 | New (1-4-2-1-42-1-4) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| 44 | ST40 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| 10 | ST52 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| 40 | CC10 (1-3-2-1-4-1-4) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 41 | ST49 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| 56 | ST142 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| 72 | ST152 | 4 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 73 | ST212 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| 92 | ST246 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| 96 | CC216 (3-4-2-2-7-2-2) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 104 | ST34 (CC34) | 9 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 104 | New (27-2v-2v-1-9-2-5) | 3 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 104 | ST145 (CC216) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 106 | CC109 (3-4-2-2-9-1-5) | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| 108 | ST133 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| A. pittii | ||||||||||||||

| 66 | NAc | 9 | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| 70 | NA | 1 | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 74 | NA | 2 | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| 74 | NA | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| 76 | NA | 1 | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 78 | NA | 6 | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| A. nosocomialis | ||||||||||||||

| 97 | NA | 1 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| 104 | NA | 26 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| 105 | NA | 49 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| 105 | NA | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis | ||||||||||||||

| 41 | NA | 7 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| 105 | NA | 4 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| 109 | NA | 2 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| 125 | NA | 2 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

Five ORFs, i.e., atpA, OXA-51, pittii-6, nosocomialis-3, and Asp-1, were used in the identification of each Acinetobacter isolate.

Seven ORFs, i.e., AB57_2484, ACICU_02042, ACICU_02966, ACICU_01870, AB57_3308, ACICU_03137, and AB57_0815, were used for calculation of the POT number of each isolate.

NA, not adopted.

After PCR, the seven SGI ORFs were scored in the order of their PCR amplicon size, with either “1” for “+”or “0” for “−” (binary code), depending on the presence or absence, respectively, of the band of amplicon DNA. These scores were then converted to decimal numbers, i.e., POT numbers. The results of each SGI binary were multiplied by 2n (n = 6 − 0) and added. For example, the binary code of ST2 (1111010) was converted to 122 as follows: 1 × 64 + 1 × 32 + 1 × 16 + 1 × 8 + 0 × 4 + 1 × 2 + 0 × 1. Furthermore, each POT number was represented by a numerical label, ranging from a POT of 0 (0000000) to a POT of 127 (1111111).

RESULTS

A total of 24 SGI candidates (Table 1) were selected by comparing the whole-genome data of the six A. baumannii strains (AB0057, AB307-0294, AYE, ACICU, ATCC 17978, and SDF). Highly conserved (95 to 100% sequence similarity) DNA sequences were found in most of the SGIs of the six A. baumannii strains checked, and nucleotide sequence identities were also observed among other A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex strains, although the sequence similarities ranged from 80% to 97%.

Strains belonging to the same CC showed very similar distribution patterns in 16 of the 24 SGI ORFs (Table 1). The CC identities of strains belonging to the major CC were identified based on the distribution patterns of those 16 SGI ORFs. However, the distribution patterns of the 16 SGI ORFs in strains of Pasteur ST145 could not be distinguished from those of a novel ST (allele numbers 27-2v-2v-1-9-2-5).

SGI ORFs adopted for multiplex PCR amplification (Table 1) were selected according to the following principles. First, ORFs that were found exclusively in international clones I or II but were absent among most clones other than the epidemic ones were selected. The ORFs specific to international clone I were AB57_0815 and AB57_3308, and those specific to international clone II were ACICU_02966 and ACICU_03137. Thus, the international clones can be identified and distinguished by detecting the four ORFs AB57_0815, AB57_3308, ACICU_02966, and ACICU_03137. Second, three ORFs (AB57_2484, ACICU_02042, and ACICU_01870) were selected, because their distribution patterns in the epidemic clones were divergent in at least two alleles compared with those found in other nonepidemic lineages. These 3 ORFs were finally adopted to improve the discriminatory power of the test. The distribution patterns of the 7 SGI ORFs among the A. baumannii clones and Acinetobacter species are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 4; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

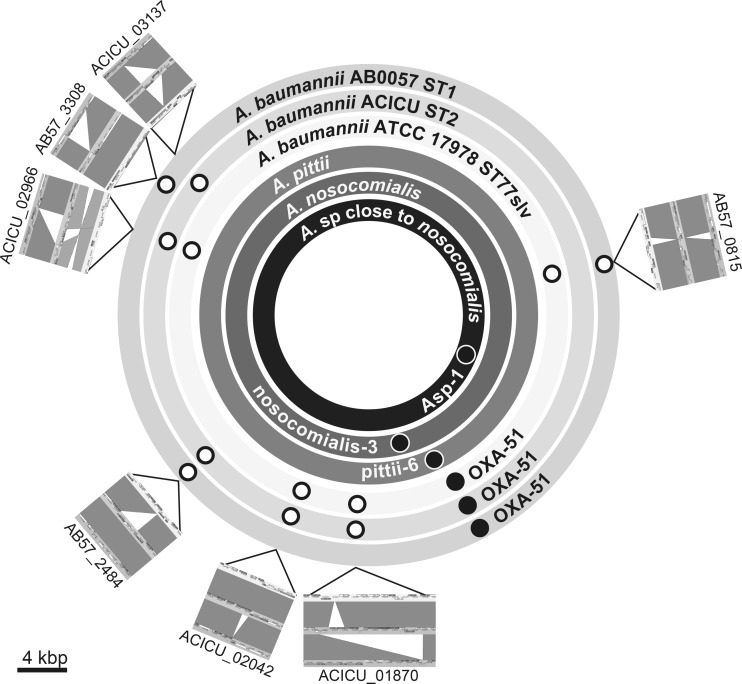

FIG 1.

Distributions of small genomic islets and species-specific markers on genomes of representative strains. Open circles indicate SGIs, and closed circles indicate species-specific genetic markers. Locations of atpA selected as the universal marker of Acinetobacter species are not provided. The genome sequence data of A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis are still draft data at present. The positions of each marker were decided by mapping the contigs containing markers on the basis of the genome of A. baumannii ACICU. Genome comparison maps illustrated by Artemis Comparison Tool (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/act/) are arranged outside the circles, indicating genomes. The outer, second outer, and third outer rings indicate the genomes of A. baumannii AB0057, ACICU, and ATCC 17978, respectively. The dark-gray drawings in genome comparison maps indicate matches between the sequences, and the silver drawing in ACICU_02966 indicates an inversion match. The calibration bar indicates 4 kbp on all seven genome comparison maps. A large color version of this figure with high resolution is available in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

Two ORFs (atpA and sucD) were selected as the candidates for universal markers of Acinetobacter species by comparing whole-genome sequences. These alleles were found among all Acinetobacter species in the BLAST databases (whole-genome sequencing [WGS] database as of 8 May 2013) showing higher percent sequence similarities (>80%) than other orthologs. atpA was finally chosen as the marker specific to Acinetobacter species and the marker for the internal control of PCR amplification.

Genetic markers specific to A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter spp. close to A. nosocomialis were also searched for their whole-genome data. ORFs designated pittii-6, nosocomialis-3, and Asp-1 (Table 2) were finally chosen as markers specific to A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter spp. close to A. nosocomialis, respectively (Table 2). The pittii-6 marker was chosen from nine candidate markers, and its specificity and sensitivity were 100% and 95%, respectively (Table 2). As pittii-6 was also found in A. calcoaceticus genome sequences, with an 83% sequence similarity in its nucleotide sequence level, primers were designed for the specific detection of A. pittii. The nosocomialis-3 marker was chosen from 3 candidates, and its specificity and sensitivity were 100% and 99%, respectively. The Asp-1 marker was chosen from 5 candidates, and its specificity and sensitivity were 100% and 100%, respectively.

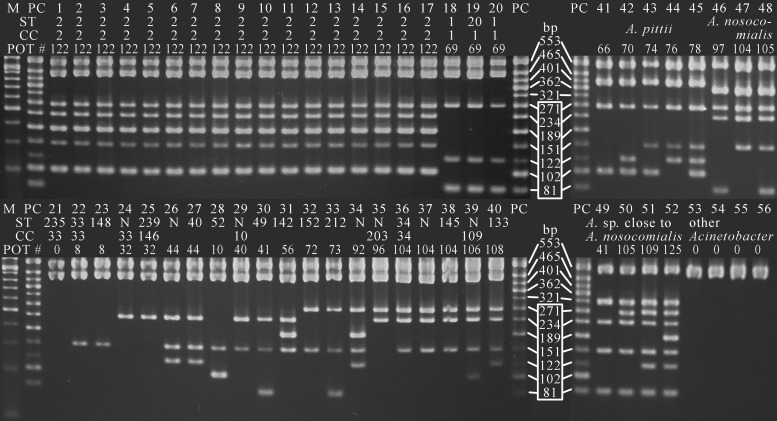

The ladder patterns of the PCR amplicons described above were clearly distinguishable by the 12-plex PCR established as the POT in the present study (Fig. 2). The same results were obtained by all four thermal cyclers we evaluated. To substantiate the 12-plex PCR, 44 A. baumannii strains used for SGI ORF screening were tested by both monoplex PCR and POT, and complete data agreement was observed between the two methods.

FIG 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis patterns of PCR-based ORF typing using 12-plex PCR. Lane M, 50-bp ladder marker; lane PC, positive control; lanes 1 to 40, A. baumannii; lanes 41 to 45, A. pittii; lanes 46 to 48, A. nosocomialis; lanes 49 to 52, Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis; lane 53, A. radioresistens; lane 54, A. ursingii; lane 55, A. bereziniae; lane 56, A. soli. International clones II (lanes 1 to 17) and I (lanes 18 to 20) showed unique patterns and can be distinguished from other A. baumannii clones (lanes 21 to 40) and other Acinetobacter species (lanes 41 to 56). The POT numbers of both A. baumannii ST49 (lane 30) and an Acinetobacter species close to A. nosocomialis (lane 49) become 41, but these isolates can apparently be discriminated from each other by the ladder patterns of the upper 5 fragments from bp 321 to bp 553. ST, sequence type; CC, clonal complex. “N” in ST lines indicates a novel ST. The ladder used for the binary digitization of the genotype of each isolate is shown in the white box. The binary numbers corresponding to each band were 1 for 81 bp, 2 for 102 bp, 4 for 122 bp, 8 for 151 bp, 16 for 189 bp, 32 for 234 bp, and 64 for 271 bp, from the bottom of the ladder in the box. The remaining 5 bands from 321 bp to 553 bp were used for the identification of Acinetobacter spp.

A total of 81 A. baumannii strains, which have been classified into 18 CCs by MLST, were analyzed by the POT method. International clones I and II were distinguished from other genetic lineages with more than two differences in the bands of their ladder patterns. According to the ladder patterns of seven ORFs, A. baumannii strains were classified into 17 POT types, 11 of which exhibited one-to-one correspondence to the CCs. Moreover, clinically isolated Acinetobacter species other than A. baumannii can be classified into three to five POT types at present (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we first showed that the newly established POT is capable of rapidly identifying A. baumannii international clones in ordinary clinical laboratories without performing nucleotide sequencing analyses of multiple genes as with MLST. To increase the feasibility of the test, the number of SGI ORFs adopted for POT was optimized. International clones I and II were fully distinguished by this method from other clones or lineages of Acinetobacter species. Moreover, the CCs of A. baumannii can be estimated by POT. The discriminatory power of POT can be controlled by optimizing the number of ORFs and loci selected for analysis. Such a newly developed POT method that compares the distribution patterns of ORFs and/or SGIs in each clinical isolate may well promise to be an easy and rapid genotyping method for identifying bacterial genetic lineages and molecular epidemiology, which is feasible in ordinary clinical microbiology laboratories.

Indeed, several methods to identify international clones using PCR have been reported (10, 11). However, they cannot identify newly emerging multidrug-resistant epidemic clones that might spread in the future. In fact, multidrug-resistant isolates other than the A. baumannii international clones have been reported (12–18). The POT method constructed in the present study is applicable to the identification of new CCs of A. baumannii or A. calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex species, including A. nosocomialis and A. pittii, in the future.

Although SGIs were first reported from Salmonella enterica in 2001 by whole-genome analysis (6), little attention has been paid to them so far. Using genomic comparisons of S. aureus strains, we found that the distribution patterns of SGI ORFs correlate with the clonal complex in S. aureus (5). In the present study, it was also proven that the distribution patterns of ORFs in SGIs correlated well with the CCs in A. baumannii. This finding indicates that a very similar concept can be applicable even to various bacterial genera, and that close correlations between the distribution patterns of SGIs and CCs may be a general phenomenon in the microbial world. In fact, the CCs of P. aeruginosa were successfully predicted with a strategy and protocol similar to those of the POT constructed in the present study (M. Suzuki and Y. Iinuma, unpublished data).

To obtain the genetic information of clinical isolates from antimicrobial resistance surveillance data, digitized numeric data provided by new genotyping methods, like the POT, contribute to easy and feasible genotyping. Since the POT is very simple and requires equipment only for PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis, this can become a routine performance method in many ordinary clinical microbiology laboratories in various countries and regions, including developing countries around the world. If many clinical microbiologists and researchers would employ the POT for genotyping of clinical isolates, they could report the genotype of each clinical isolate as a digitized numeric number, and this would make it very easy to quickly compare the genotypes of clinical isolates with those of other clinical isolates recovered in different continents or areas. Therefore, the POT would enable us to identify newly emerging genetic lineages in the very early stage of their outbreak. Present weak antimicrobial resistance surveillance and monitoring systems depending mainly on the antimicrobial resistance phenotypes of clinical isolates can be reinforced from the genetic viewpoint by using the POT instead of MLST.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tetsuya Yagi of Nagoya University, Jun Yatsuyanagi of the Akita Prefectural Research Center for Public Health and Environment, and Keigo Shibayama of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan, for their kind provision of clinical isolates.

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (grants H21-Shinko-Ippan-008, H24-Shinko-Ippan-010, and H25-Shinko-Ippan-003).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01064-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sabat AJ, Budimir A, Nashev D, Sá-Leão R, van Dijl Jm Laurent F, Grundmann H, Friedrich AW, ESCMID Study Group of Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM) 2013. Overview of molecular typing methods for outbreak detection and epidemiological surveillance. Euro Surveill. 18:pii=20380 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kempf M, Rolain JM. 2012. Emergence of resistance to carbapenems in Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe: clinical impact and therapeutic options. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39:105–114. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarrilli R, Pournaras S, Giannouli M, Tsakris A. 2013. Global evolution of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal lineages. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 41:11–19. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Tawada Y, Kato M, Hori H, Mamiya N, Hayashi Y, Nakano M, Fukushima R, Katai A, Tanaka T, Hata M, Matsumoto M, Takahashi M, Sakae K. 2006. Development of a rapid strain differentiation method for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Japan by detecting phage-derived open-reading frames. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:938–947. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki M, Matsumoto M, Takahashi M, Hayakawa Y, Minagawa H. 2009. Identification of the clonal complexes of Staphylococcus aureus strains by determination of the conservation patterns of small genomic islets. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107:1367–1374. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkhill J, Dougan G, James KD, Thomson NR, Pickard D, Wain J, Churcher C, Mungall KL, Bentley SD, Holden MT, Sebaihia M, Baker S, Basham D, Brooks K, Chillingworth T, Connerton P, Cronin A, Davis P, Davies RM, Dowd L, White N, Farrar J, Feltwell T, Hamlin N, Haque A, Hien TT, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Krogh A, Larsen TS, Leather S, Moule S, O'Gaora P, Parry C, Quail M, Rutherford K, Simmonds M, Skelton J, Stevens K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413:848–852. 10.1038/35101607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Scola B, Gundi VA, Khamis A, Raoult D. 2006. Sequencing of the rpoB gene and flanking spacers for molecular identification of Acinetobacter species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:827–832. 10.1128/JCM.44.3.827-832.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver T, Berriman M, Tivey A, Patel C, Böhme U, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Rajandream MA. 2008. Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 24:2672–2676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turton JF, Woodford N, Glover J, Yarde S, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL. 2006. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the blaOXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2974–2976. 10.1128/JCM.01021-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turton JF, Gabriel SN, Valderrey C, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL. 2007. Use of sequence-based typing and multiplex PCR to identify clonal lineages of outbreak strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:807–815. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui M, Suzuki S, Suzuki M, Arakawa Y, Shibayama K. 2013. Rapid discrimination of Acinetobacter baumannii international clone II lineage by pyrosequencing SNP analyses of bla(OXA-51-like) genes. J. Microbiol. Methods 94:121–124. 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decousser JW, Jansen C, Nordmann P, Emirian A, Bonnin RA, Anais L, Merle JC, Poirel L. 2013. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in France, January to May 2013. Euro Surveill. 18:31 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tena D, Martínez NM, Oteo J, Sáez D, Vindel A, Azañedo ML, Sánchez L, Espinosa A, Cobos J, Sánchez R, Otero I, Bisquert J. 2013. Outbreak of multiresistant OXA-24- and OXA-51-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in an internal medicine ward. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 66:323–326. 10.7883/yoken.66.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed-Bentley J, Chandran AU, Joffe AM, French D, Peirano G, Pitout JD. 2013. Gram-negative bacteria that produce carbapenemases causing death attributed to recent foreign hospitalization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:3085–3091. 10.1128/AAC.00297-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempf M, Rolain JM, Azza S, Diene S, Joly-Guillou ML, Dubourg G, Colson P, Papazian L, Richet H, Fournier PE, Ribeiro A, Raoult D. 2013. Investigation of Acinetobacter baumannii resistance to carbapenems in Marseille hospitals, south of France: a transition from an epidemic to an endemic situation. APMIS 121:64–71. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuetz AN, Huard RC, Eshoo MW, Massire C, Della-Latta P, Wu F, Jenkins SG. 2012. Identification of a novel Acinetobacter baumannii clone in a US hospital outbreak by multilocus polymerase chain reaction/electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72:14–19. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acosta J, Merino M, Viedma E, Poza M, Sanz F, Otero JR, Chaves F, Bou G. 2011. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii harboring OXA-24 carbapenemase, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1064–1067. 10.3201/eid/1706.091866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong Q, Xu W, Wu Y, Xu H. 2012. Clonal spread of carbapenem non-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit in a teaching hospital in China. Ann. Lab. Med. 32:413–419. 10.3343/alm.2012.32.6.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartual SG, Seifert H, Hippler C, Luzon MA, Wisplinghoff H, Rodrìguez-Valera F. 2005. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4382–4390. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4382-4390.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.