Abstract

Matched vaginal and cervical specimens from 96 subjects were analyzed by quantitative PCR for the presence and concentration of bacterial vaginosis-associated microbes and commensal Lactobacillus spp. Detection of these microbes was 92% concordant, indicating that microbial floras at these body sites are generally similar.

TEXT

The vaginal microbiome plays an important role in female reproductive tract health. The vaginal microbiome of healthy women generally falls into one of five categories, four of which are dominated by a single lactobacillus species (Lactobacillus crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, or L. jensenii) and the fifth of which is characterized by diverse anaerobic and facultative species (1). This final group has traditionally been associated with bacterial vaginosis (BV), a disease characterized by vaginal discharge and odor (2), as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission (3), Trichomonas vaginalis infection (4), and preterm labor (5). Although less well studied, the cervical microbiome may arguably be of greater relevance, as the cervix is the site of infection by numerous pathogens, such as HIV, human papillomavirus (HPV), Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. A recent study found that a lactobacillus-dominated cervical microbiome is inversely associated with the prevalence of HIV, herpes simplex virus type 2, and high-risk human papillomavirus (6). Studies evaluating the cervicovaginal flora have variously sampled the cervix, the vagina, or both sites simultaneously. Therefore, it is of general interest to comparatively analyze the flora at these sites to determine if results generated from sampling the vagina can be generalized to the cervix and vice versa. For example, the cervical transformation zone is enriched in T cells and antigen-presenting cells compared to the vagina (7), and thus, differential immune responses at these sites could impact the composition of their respective microbiomes. To our knowledge, only two prior studies have addressed this issue (8, 9), and although informative, these studies analyzed small subject cohorts and utilized semiquantitative methodology. Our goal in this study was to quantitatively analyze the cervical and vaginal floras with respect to lactobacillus species as well as microbes associated with abnormal floras, such as BV, from a substantial subject cohort.

We performed a cross-sectional study from a prospective cohort, enrolling subjects who were receiving ambulatory gynecologic care at either the Care Center for Women at University of Florida Health (a teaching hospital with related ambulatory clinics) or the University of Florida Southside Women's Health Specialists (a freestanding ambulatory care center). The study took place from May 2006 to June 2009. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was carried out with the approval of Western Institutional Review Board. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the microbiology and immunology of BV. Therefore, subjects were recruited who were either complaining of vaginitis symptoms (e.g., itching, discharge or odor) or attending for well visits or routine care. Subject information was collected by having subjects complete a questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy and menopausal or postmenopausal status, as these conditions are known to influence the composition of the vaginal flora (10, 11). In addition, patients were excluded if they were positive for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, or Trichomonas vaginalis, as these infections can provoke cervical and/or vaginal inflammation, which could confound immunological analysis of BV. In this study, we analyzed separate vaginal and cervical specimens from 96 subjects. Subject ages ranged from 18 to 54 years, with an average of 31.4 years. Race was self-reported; 44 subjects (46%) were Caucasian, 43 (45%) were African American, 9 (9.4%) were Hispanic, 1 was Asian (1.0%), and 1 was “other” (1.0%). Patients were diagnosed for BV using the following signs and symptoms: (i) vaginal discharge, (ii) odor, (iii) elevated vaginal pH, and (iv) the presence of clue cells (exfoliated vaginal epithelial cells with attached bacteria) (i.e., Amsel's criteria) (12). Twenty-four subjects (25%) were diagnosed as having BV (3 or 4 Amsel's criteria), 21 subjects (22%) neither had BV nor were completely healthy (1 or 2 Amsel's criteria), and 51 subjects (53%) were healthy (0 Amsel's criteria). Specimens were collected with OneSwab collection devices (Medical Diagnostic Laboratories). After a vaginal speculum was placed and the cervix was visualized, the os was swabbed. Immediately thereafter, a second swab was taken from the left or right midvaginal sidewall. These samples were stored at 4°C overnight and shipped to Medical Diagnostic Laboratories, where they were stored at −20°C until analyzed. DNA was extracted from OneSwab transport medium by the X-tractor Gene automated nucleic acid extraction system (Corbett Robotics, San Francisco, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A panel of quantitative real time-PCR assays was used to quantify DNA from BV-associated microbes and commensal lactobacillus species (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The targets of these reactions are as follows: A. vaginae (tuf, encoding elongation factor Tu), BVAB2 (BV-associated bacterium 2) (16S rRNA gene) (13), G. vaginalis (hisC, encoding histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase), Megasphaera spp. (16S rRNA gene) (13), and lactobacillus species (tuf, encoding elongation factor Tu) (14). All assays have a limit of detection of ≤10 copies of target per reaction, do not cross-react with DNA from a diverse panel of microbes commonly found in the female reproductive tract, and exhibit linear amplification from 101 to 108 target copies per reaction (14) (data not shown). All reaction plates included 4 separate no-template control wells. The quantity of PCR target copies detected is expressed per reaction, each one using 0.5 μl of DNA as the template in a 4-μl reaction mixture. The final primer concentrations were 200 to 800 nM. All of the reactions were run using the following conditions: 2 min at 50°C and 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C (melting) and 45 s at 60°C (annealing and extension). The Megasphaera reaction was run as a duplex PCR using both type 1 and type 2 probes, and the Lactobacillus PCR was run as a multiplex, using probes for L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, and L. jensenii. All reactions were performed using a CFX384 real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad). For each reaction, a standard curve was generated using reactions with 102, 104, or 106 copies of a plasmid encoding the amplification target. The distribution of PCR target copy concentration in patient specimens was nonnormal (D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test). Therefore, to detect correlations, we determined Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. Only comparisons that remained significant after controlling for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction are reported. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5.02 (GraphPad). For significance testing, an alpha value of 0.05 was used.

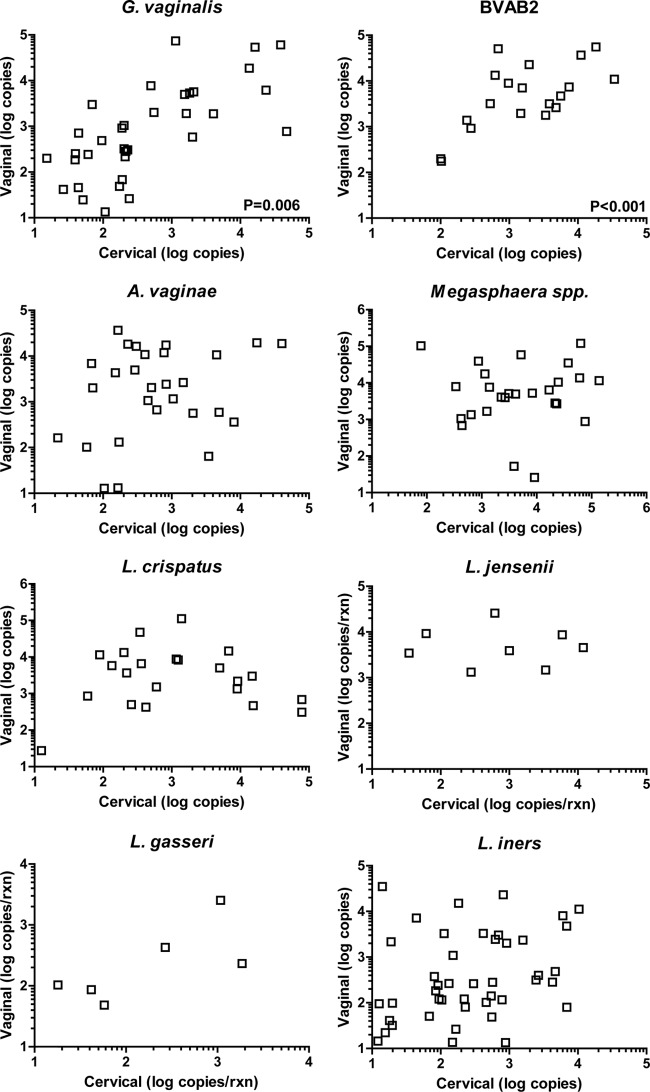

We compared cervical and vaginal specimens from the same patients to determine concordance for detection for these microbes (Table 1). We found high concordance rates: 95% for A. vaginae, Megasphaera spp., and L. jensenii; 94% for BVAB2 and L. crispatus; 93% for L. gasseri; 85% for G. vaginalis; and 81% for L. iners. In total, 705 out of 768 test results were concordant between specimens for each patient, for an overall concordance rate of 92%. Of these concordant results, 188 were matched positive specimens and 517 were matched negative specimens. Of the 63 instances of discordant test results, 29 involved positive cervical specimens and negative vaginal specimens, and 34 were the converse. We next analyzed swab pairs where at least one was positive for the quantity of PCR target in each sample (Fig. 1). We found that concentrations at the two sites were correlated for G. vaginalis (P = 0.006, ρ = 0.41) and BVAB2 (P < 0.001, ρ = 0.67). No significant correlations were observed for the other microbes detected. In addition, there were no significant differences in the concentration of genomic copies of individual microbes when cervical and vaginal specimens were compared (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Concordance for detection of microbial genomic DNA in matched specimens from 96 subjects

| Organism | No. (%) of specimensa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant |

Discordant |

|||||

| Total | Cer+ Vag+ | Cer− Vag− | Total | Cer+ Vag− | Cer− Vag+ | |

| G. vaginalis | 82 (85) | 34 (35) | 48 (50) | 14 (15) | 7 (7.3) | 7 (7.3) |

| A. vaginae | 91 (95) | 28 (29) | 63 (66) | 5 (5.2) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| BVAB2 | 90 (94) | 19 (20) | 71 (74) | 6 (6.3) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| Megasphaera spp. | 91 (95) | 26 (27) | 65 (68) | 5 (5.2) | 4 (4.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| L. crispatus | 90 (94) | 23 (24) | 67 (70) | 6 (6.3) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| L. gasseri | 89 (93) | 6 (6.3) | 83 (86) | 7 (7.3) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (5.2) |

| L. jensenii | 91 (95) | 8 (8.3) | 83 (86) | 5 (5.2) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| L. iners | 78 (81) | 40 (39) | 38 (40) | 15 (16) | 6 (6.3) | 9 (9.4) |

| Total | 705 (92) | 188 (24) | 517 (67) | 63 (8.2) | 29 (3.8) | 34 (4.4) |

Cer, cervical specimen; Vag, vaginal specimen.

FIG 1.

Quantity of PCR target copies measured in matched cervical and vaginal specimens. P values are displayed for significant correlations. Due to the log scale, discordant samples (where one sample has a value of zero) are not displayed.

The frequent cocolonization of the cervix and vagina with the same microbes is not surprising in light of the essentially continuous nature of the lower female reproductive tract. Interestingly, only two of the eight microbes assayed—G. vaginalis and BVAB2—were correlated with respect to quantity at the two sites. Studies of G. vaginalis have found that virulent strains are superior to commensal strains in their ability to adhere to both vaginal (15) and cervical (16) epithelium, which may contribute to the correlated concentrations we observed at these sites. In addition, G. vaginalis has a highly diverse population structure (17), and cocolonization with multiple strains is common (18); it is possible that one strain predominates at the cervix and the other in the vagina. BVAB2 and vaginal Megasphaera spp. have not yet been cultured in the laboratory, so their adherence properties are unknown; although A. vaginae has been cultured, relevant studies are also lacking. With respect to lactobacillus, a study of human vaginal isolates found that they varied greatly in their ability to adhere to vaginal epithelial cells (19). In addition, an adhesin has been identified in L. crispatus that specifically mediates adherence to stratified squamous epithelium (including vaginal epithelium) but not to columnar epithelium (which constitutes the cervical epithelium), and its expression is strain specific (20). Therefore, we speculate that some strains of lactobacillus may be differentially able to colonize the two sites, resulting in the poor correlation we observed.

One major possible confounding factor in this study is contamination. One trivial explanation for similarity between cervical and vaginal flora is that cross-contamination occurred during sampling. Based upon physical anatomy, it is highly unlikely that a vaginal specimen would be contaminated with cervical flora; in contrast, it is more plausible than a cervical specimen could come in contact with the vaginal wall after sampling, resulting in contamination with vaginal flora. There are several observations that lead us to reject cross-contamination as the most likely explanation for our observations. First, of the 63 instances of discordance, 29 of them (46%) were positive cervical specimens and negative vaginal specimens, which cannot be explained by contamination of cervical specimens with vaginal flora. Second, we chose to analyze specimens which were concordant for multiple organisms and compared the concentration, as we would expect to observe a consistently higher concentration in vaginal specimens if systematic contamination occurred. However, among 52 such subjects, we found that for 24 of them (46%), at least one microbe was present at a higher concentration in the cervical specimen than in the vaginal specimen. Again, this pattern argues against cross-contamination as an explanation for the cervical-vaginal concordance. However, future studies could consider the utilization of sham cervical samples as a control for cross-contamination.

With respect to prior studies examining cervical and vaginal flora, Kim et al. analyzed a cohort of eight subjects, from whom samples were obtained from the cervix and several vaginal sites using lavage, swabbing, and scraping, and PCR amplified 16S rRNA genes, generated amplicon libraries, and sequenced them to evaluate microbial community composition (8). Their results were broadly similar to ours, in that the same microbes, such as Lactobacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and G. vaginalis, were detected at the cervix and vagina in the same subjects but their concentrations varied greatly. The method used in that study was advantageous in that it is unbiased in detection; however, it is only semiquantitative and failed to resolve the lactobacillus detected to the species level. Another study, using DNA hybridization, analyzed cervical and vaginal specimens from 12 patients and also found that microbes such as G. vaginalis, A. vaginae, and L. iners were present in both specimens from the same patients (9). Again, quantitative PCR is superior to DNA hybridization with respect to sensitivity and quantitation. In summary, utilizing quantitative PCR methods to analyze a series of BV-associated and commensal lactobacillus species, we found a high overall degree of concordance with respect to colonization, although the quantities of a particular microbe detected at both sites varied substantially. With respect to diagnostic testing for the microbes in question, cervical and vaginal specimens are generalizable with respect to qualitative detection; however, quantitative methodology may require independent validation for cervical and vaginal specimens.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00795-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. 2011. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108(Suppl 1):S4680–S4687. 10.1073/pnas.1002611107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel JD. 1997. Vaginitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1896–1903. 10.1056/NEJM199712253372607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirmonsef P, Krass L, Landay A, Spear GT. 2012. The role of bacterial vaginosis and trichomonas in HIV transmission across the female genital tract. Curr. HIV Res. 10:202–210. 10.2174/157016212800618165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin DH, Zozaya M, Lillis RA, Myers L, Nsuami MJ, Ferris MJ. 2013. Unique vaginal microbiota that includes an unknown Mycoplasma-like organism is associated with Trichomonas vaginalis infection. J. Infect. Dis. 207:1922–1931. 10.1093/infdis/jit100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, Krohn MA, Gibbs RS, Martin DH, Cotch MF, Edelman R, Pastorek JG, II, Rao AV, McNellis D, Regan JA, Carey JC, Klebanoff MA. 1995. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:1737–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgdorff H, Tsivtsivadze E, Verhelst R, Marzorati M, Jurriaans S, Ndayisaba GF, Schuren FH, van de Wijgert JH. 6 March 2014. Lactobacillus-dominated cervicovaginal microbiota associated with reduced HIV/STI prevalence and genital HIV viral load in African women. ISME J. 10.1038/ismej.2014.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pudney J, Quayle AJ, Anderson DJ. 2005. Immunological microenvironments in the human vagina and cervix: mediators of cellular immunity are concentrated in the cervical transformation zone. Biol. Reprod. 73:1253–1263. 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim TK, Thomas SM, Ho M, Sharma S, Reich CI, Frank JA, Yeater KM, Biggs DR, Nakamura N, Stumpf R, Leigh SR, Tapping RI, Blanke SR, Slauch JM, Gaskins HR, Weisbaum JS, Olsen GJ, Hoyer LL, Wilson BA. 2009. Heterogeneity of vaginal microbial communities within individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1181–1189. 10.1128/JCM.00854-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikolaitchouk N, Andersch B, Falsen E, Strombeck L, Mattsby-Baltzer I. 2008. The lower genital tract microbiota in relation to cytokine-, SLPI- and endotoxin levels: application of checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization (CDH). APMIS 116:263–277. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, Tarca AL, Fadrosh DW, Nikita L, Galuppi M, Lamont RF, Chaemsaithong P, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, Ravel J. 2014. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. Microbiome 2:4. 10.1186/2049-2618-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brotman RM, Shardell MD, Gajer P, Fadrosh D, Chang K, Silver MI, Viscidi RP, Burke AE, Ravel J, Gravitt PE. 2014. Association between the vaginal microbiota, menopause status, and signs of vulvovaginal atrophy. Menopause 21:450–458. 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a4690b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. 1983. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am. J. Med. 74:14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Thomas KK, Oakley BB, Marrazzo JM. 2007. Targeted PCR for detection of vaginal bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3270–3276. 10.1128/JCM.01272-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balashov SV, Mordechai E, Adelson ME, Sobel JD, Gygax SE. 2014. Multiplex quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay for the identification and quantitation of major vaginal lactobacilli. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 78:321–327. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harwich MD, Jr, Alves JM, Buck GA, Strauss JF, III, Patterson JL, Oki AT, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK. 2010. Drawing the line between commensal and pathogenic Gardnerella vaginalis through genome analysis and virulence studies. BMC Genomics 11:375. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro J, Henriques A, Machado A, Henriques M, Jefferson K, Cerca N. 2013. Reciprocal interference between Lactobacillus spp. and Gardnerella vaginalis on initial adherence to epithelial cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 10:1193–1198. 10.7150/ijms.6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A, Earl J, Retchless A, Hillier SL, Rabe LK, Cherpes TL, Powell E, Janto B, Eutsey R, Hiller NL, Boissy R, Dahlgren ME, Hall BG, Costerton JW, Post JC, Hu FZ, Ehrlich GD. 2012. Comparative genomic analyses of 17 clinical isolates of Gardnerella vaginalis provide evidence of multiple genetically isolated clades consistent with subspeciation into genovars. J. Bacteriol. 194:3922–3937. 10.1128/JB.00056-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balashov SV, Mordechai E, Adelson ME, Gygax SE. 2014. Identification, quantification and subtyping of Gardnerella vaginalis in noncultured clinical vaginal samples by quantitative PCR. J. Med. Microbiol. 63:162–175. 10.1099/jmm.0.066407-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreu A, Stapleton AE, Fennell CL, Hillier SL, Stamm WE. 1995. Hemagglutination, adherence, and surface properties of vaginal Lactobacillus species. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1237–1243. 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelman SM, Lehti TA, Kainulainen V, Antikainen J, Kylvaja R, Baumann M, Westerlund-Wikstrom B, Korhonen TK. 2012. Identification of a high-molecular-mass Lactobacillus epithelium adhesin (LEA) of Lactobacillus crispatus ST1 that binds to stratified squamous epithelium. Microbiology 158:1713–1722. 10.1099/mic.0.057216-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.